Chris Hedges's Blog, page 154

September 13, 2019

UAW Extends Ford, Fiat Chrysler Pacts; Strike Possible at GM

DETROIT — Leaders of the United Auto Workers union have extended contracts with Ford and Fiat Chrysler indefinitely, but the pact with General Motors is still set to expire Saturday night.

The move puts added pressure on bargainers for both sides as they approach the contract deadline and the union starts to make preparations for a strike.

The contract extension was confirmed Friday by UAW spokesman Brian Rothenberg, who declined further comment on the talks.

Related Articles

Have Democrats Abandoned Ohio Auto Workers to Trump?

by

Trump's Labor Day Attacks on Workers

by

The union has picked GM as the target company, meaning it is the focus of bargaining and would be the first company to face a walkout. GM’s contract with the union is scheduled to expire at 11:59 p.m. Saturday.

It’s possible that the four-year GM contract also could be extended or a deal could be reached, but it’s more likely that 49,200 UAW members could walk out of GM plants as early as Sunday because union and company demands are so far apart.

Picket line schedules already have been posted near the entrance to one local UAW office in Detroit.

Art Wheaton, an auto industry expert at the Worker Institute at Cornell University, expects the GM contract to be extended for a time, but he says the gulf between both sides is wide.

“GM is looking through the windshield ahead, and it looks like nothing but land mines,” he said of a possible recession, trade disputes and the expense of developing electric and autonomous vehicles. “I think there’s really going to be a big problem down the road in matching the expectations of the union and the willingness of General Motors to be able to give the membership what it wants.”

Plant-level union leaders from all over the country will be in Detroit on Sunday to talk about the next steps, and after that, the union likely will make an announcement.

But leaders are likely to face questions about an expanding federal corruption probe that snared a top official on Thursday. Vance Pearson, head of a regional office based near St. Louis, was charged with corruption in an alleged scheme to embezzle union money and spend cash on premium booze, golf clubs, cigars and swanky stays in California. It’s the same region that UAW President Gary Jones led before taking the union’s top office last year.

Jones and other union executives met privately at a hotel at Detroit Metropolitan Airport on Friday. After the meeting broke up, Jones’ driver and others physically blocked an AP reporter from trying to approach him to ask questions.

In a 40-page criminal complaint, the government alleged that over $600,000 in UAW money was spent by union officials at businesses in the Palm Beach, California, area, including at restaurants, a golf resort, cigar shop and rental properties, between 2014 and 2017.

The union said the government has misconstrued facts and said the allegations are not proof of wrongdoing. “Regardless, we will not let this distract us from the critical negotiations under way with GM to gain better wages and benefits,” Rothenberg said.

At UAW Local 22 in Detroit, picket line schedules for three days were posted on the lobby windows. The local represents workers at a plant that straddles the border between Detroit and the hamlet of Hamtramck.

The 24-hour schedules don’t list any date to start but a separate schedule has a group reporting to the union hall at 6 a.m. on Sunday. The factory, which makes the Chevrolet Impala and Cadillac CT6, is one of four that GM plans to close.

Here are the main areas of disagreement:

— GM is making big money, $8 billion last year alone, and workers want a bigger slice. The union wants annual pay raises to guard against an economic downturn, but the company wants to pay lump sums tied to earnings. Automakers don’t want higher fixed costs.

— The union also wants new products for four factories GM wants to close. The factory plans have irked some workers, although most those who were laid off will get jobs at other GM factories. GM currently has too much U.S. factory capacity.

— The companies want to close the labor cost gap with workers at plants run by foreign automakers. GM’s gap is the largest at $13 per hour, followed by Ford at $11 and Fiat Chrysler at $5, according to figures from the Center for Automotive Research, an industry think tank. GM pays $63 per hour in wages and benefits compared with $50 at the foreign-owned factories.

— Union members have great health insurance plans but workers pay about 4% of the cost. Employees of large firms nationwide pay about 34%, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The companies would like to cut costs.

If there is a strike, it would be the union’s first since a short one against GM in 2007.

The union may have to strike at least for a while to show workers that it got as much from the company as it could, Wheaton said. Some workers, he said, mistrust union leaders due to the corruption scandal.

Negotiators are usually tight-lipped about the talks, but a week ago, Vice President Terry Dittes wrote in a letter to local union leaders that GM has been slow to respond to union proposals. GM answered in a letter sent to factories that said it is moving as quickly as it can.

“We are working hard to understand and respond to UAW proposals and we have offered to meet as often as needed,” the letter said.

Snowden Tells Life Story and Why He Leaked in New Memoir

WASHINGTON — Former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden has written a memoir, telling his life story in detail for the first time and explaining why he chose to risk his freedom to become perhaps the most famous whistleblower of all time.

Snowden, who now lives in Russia to avoid prosecution in the U.S., says his seven years working for the NSA and CIA led him to conclude the U.S. intelligence community “hacked the Constitution” and put everyone’s liberty at risk and that he had no choice but to turn to journalists to reveal it to the world.

“I realized that I was crazy to have imagined that the Supreme Court, or Congress, or President Obama, seeking to distance his administration from President George W. Bush’s, would ever hold the IC legally responsible — for anything,” he writes.

Related Articles

Edward Snowden Leads Chorus Condemning Assange's Arrest

by

VIDEO: The Edward Snowden Interview the U.S. Media Didn't Want You to Watch

by Natasha Hakimi Zapata

Scapegoating Edward Snowden Is 'Irrational' and Troubling, Advocates Warn

by

The book, “Permanent Record,” is scheduled to be released Tuesday. It offers by far the most expansive and personal account of how Snowden came to reveal secret details about the government’s mass collection of Americans’ emails, phone calls and internet activity in the name of national security.

His decision to turn from obscure IC wonk to whistleblower in 2013 set off a national debate about the extent of government surveillance by intelligence agencies desperate to avoid a repeat of the Sept. 11 attacks. Intelligence officials who conduct annual classified assessments of damage from Snowden’s disclosures say the documents will continue trickling out into the public domain for years to come.

Though the book comes six years after the disclosures, Snowden, who fled first to Hong Kong and then Russia, attempts in his memoir to place his concerns in a contemporary context. He sounds the alarm about what he sees as government efforts worldwide to delegitimize journalism, suppress human rights and support authoritarian movements.

“What is real is being purposely conflated with what is fake, through technologies that are capable of scaling that conflation into unprecedented global confusion,” he says.

The story traces Snowden’s evolution from childhood, from growing up in the 1980s in North Carolina and suburban Washington, where his mother worked as a clerk at the NSA and his father served in the Coast Guard.

He came of age as the internet evolved from an obscure government computer network and describes how a youthful fascination with technology — as a child, he took apart and reassembled a Nintendo console and, as a teenager, hacked the Los Alamos nuclear laboratory network — eventually led him to a career as an NSA contractor, where he observed high-tech spy powers with increasing revulsion.

Analysts used the government’s collection powers to read the emails of current and former lovers and stalk them online, he writes.

One particular program the NSA called XKEYSCORE allowed the government to scour the recent internet history of average Americans. He says he learned through that program that nearly everyone who’s been online has at least two things in common: They’ve all watched pornography at one time or another, and they’ve all stored videos and pictures of their family.

“This was true,” he writes, “for virtually everyone of every gender, ethnicity, race, and age — from the meanest terrorist to the nicest senior citizen, who might be the meanest terrorist’s grandparent, or parent, or cousin.”

He struggled to share his concerns with his girlfriend, who joined him in Russia and is now his wife.

“I couldn’t tell her that my former co-workers at the NSA could target her for surveillance and read the love poems she texted me. I couldn’t tell her that they could access all the photos she took — not just the public photos, but the intimate ones,” he writes. “I couldn’t tell her that her information was being collected, that everyone’s information was being collected, which was tantamount to a government threat: If you ever get out of line, we’ll use your private life against you.”

Before summoning a small group of journalists to Hong Kong to disclose classified secrets, knowing that a return to the U.S. was impossible, he says he prepared like a man about to die. He emptied his bank accounts, put cash into a steel ammo box for his girlfriend and erased and encrypted his old computers.

These days, the 36-year-old Snowden lives in Moscow, where he remains outside the reach of a U.S. Justice Department that brought Espionage Act charges just weeks after the disclosures. He spends many of his days behind a computer and participating in virtual meetings with fellow board members at the Freedom of the Press Foundation. “I beam myself onto stages around the world” to discuss civil liberties, he writes.

When he does go out, he tries to shake up his appearance, sometimes wearing different glasses. He keeps his head down when he walks past buildings equipped with closed-circuit television. Once, he says, he was recognized in a Moscow museum and consented to a selfie request from a teenage girl speaking German-accented English.

It’s unclear when or even if Snowden will return to a country where his family has deep roots. He traces his lineage back to the Mayflower and ancestors who fought in the Revolutionary War.

He was shaken by the Sept. 11 attacks, but describes his “reflexive, unquestioning support” for the wars that followed as the greatest regret of his life.

“It was as if whatever institutional politics I’d developed had crashed — the anti-institutional hacker ethos instilled in me online, and the apolitical patriotism I’d inherited from my parents, both wiped from my system — and I’d been rebooted as a willing vehicle of vengeance.”

Huffman Gets 14 Days Behind Bars in College Admissions Scam

BOSTON — “Desperate Housewives” star Felicity Huffman was sentenced Friday to 14 days in prison for paying $15,000 to rig her daughter’s SAT scores in the college admissions scandal that ensnared dozens of wealthy and well-connected parents.

Huffman, 56, became the first of 34 parents to be sentenced in the case. She was also given a $30,000 fine, 250 hours of community service and a year of supervised release.

Before sentencing, she tearfully described her daughter asking why Huffman didn’t trust her.

Related Articles

The Rich Have Bought Their Way Into Elite Colleges for Decades

by

Test Taker Pleads Guilty in College Admissions Bribery Scam

by

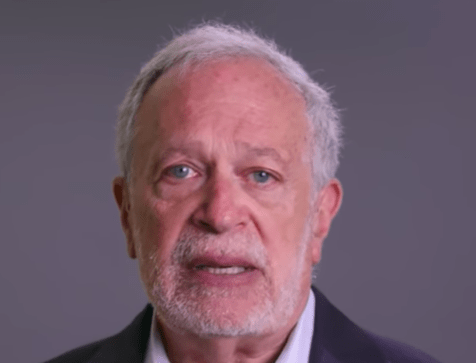

Robert Reich: America's Meritocracy Is a Cruel Joke

by Robert Reich

“I can only say I am so sorry, Sophia,” Huffman said. “I was frightened. I was stupid, and I was so wrong. I am deeply ashamed of what I have done. I have inflicted more damage than I could ever imagine. I now see all the things that led me down this road, but ultimately none of the reasons matter because at the end of the day I had a choice. I could have said no.”

A total of 51 people have been charged in the scheme, the biggest college admissions case ever prosecuted by the Justice Department.

In his argument for incarceration, Assistant U.S. Attorney Eric Rosen said Friday that prosecutors had no reason to doubt the rationale she offered — her fears and insecurities as a parent — for taking part in the scheme.

“But with all due respect to the defendant, welcome to parenthood,” Rosen said. “Parenthood is terrifying, exhausting and stressful, but that’s what every parent goes through. … What parenthood does not do, it does not make you a felon, it does not make you cheat, in fact it makes you want to serve as a positive role model for your children.”

Huffman’s lawyer Martin Murphy argued that her crimes were less serious than those of her co-defendants, noting that she paid a low amount and that, unlike others, she did not enlist her daughter in the scheme.

“One of the key things the court should do is to impose a sentence that treats Ms. Huffman like other similarly situated defendants, not treat her more harshly because of her wealth and fame, or treat her more favorably because of her wealth and fame,” Murphy said.

The scandal has embroiled elite universities across the country, including Yale, Stanford, Georgetown and UCLA. It exposed the lengths to which parents will go to get their children into the “right” schools and reinforced suspicions that the college admissions process is slanted toward the rich.

Prosecutors said parents schemed to manipulate test scores and bribed coaches to get their children into elite schools by having them labeled as recruited athletes for sports they didn’t even play.

Huffman pleaded guilty in May to a single count of conspiracy and fraud as part of a deal with prosecutors.

Prosecutors had requested prison time to send the message that white-collar criminals can’t simply buy their way out of jail.

But her lawyers argued that Huffman was only a “customer” in a broader scheme orchestrated by others. In past cases involving cheating or academic fraud, they said, only the ringleaders went to prison.

The case is seen as an indicator of what’s in store for other defendants. Over the next two months, nearly a dozen other parents are scheduled to be sentenced. Fifteen parents have pleaded guilty, while 19 are fighting the charges.

Among those contesting the charges are “Full House” actress Lori Loughlin and her fashion designer husband, Mossimo Giannulli, who are accused of paying to get their two daughters into the University of Southern California as fake athletes.

Former Stanford University sailing coach John Vandemoer is the only other person sentenced so far and received a day in prison. He admitted helping students get into Stanford as recruited athletes in exchange for $270,000 for his sailing program.

Huffman paid $15,000 to boost her older daughter Sofia’s SAT scores with the help of William “Rick” Singer, an admission consultant at the center of the scheme. Singer, who has pleaded guilty, allegedly bribed a test proctor to correct the teenager’s answers.

Authorities said Huffman’s daughter got a bump of 400 points from her earlier score on the PSAT, a practice version of the SAT.

The actress has said her daughter was unaware of the arrangement.

In a letter this month asking for leniency, Huffman said she carries “a deep and abiding shame” and recognizes that she broke the law and betrayed her family. She said she turned to the scheme after her daughter’s dreams of going to college and pursuing an acting career were jeopardized by her low math score.

“I honestly didn’t and don’t care about my daughter going to a prestigious college,” Huffman wrote. “I just wanted to give her a shot at being considered for a program where her acting talent would be the deciding factor.”

Prosecutors countered that Huffman was driven by “a sense of entitlement, or at least moral cluelessness, facilitated by wealth and insularity.”

“Millions of parents send their kids to college every year. All of them care as much she does about their children’s fortunes,” they said in court papers. “But they don’t buy fake SAT scores and joke about it (‘Ruh Ro!’) along the way.”

Huffman used the Scooby-Doo catchphrase in an email after her daughter’s high school tried to make her take the exam with its own proctor instead of one preferred by Singer.

Prosecutors have not said which colleges her daughter applied to with the fraudulent SAT score.

Huffman’s husband, actor William H. Macy, was not charged.

The amount Huffman paid is relatively low compared with other bribes alleged in the scheme. Some parents are accused of paying up to $500,000.

Resisting a World That Privileges Whiteness—While We Still Can

“My Time Among the Whites: Notes From an Unfinished Education”

A book by Jennine Capó Crucet

In the past couple of years, a new trend has emerged that can best be described as post-Trump Latinx literature. By “post-Trump,” I mean a nascent body of literature that critiques Trump and the ideology he represents, a counter-archive to the white supremacy that dominates the news. As Latinx authors contend with Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric, which casts all immigrants as Mexicans and all Mexicans as criminals, this work has been a site of resistance, of hope, of sorrow.

This still-forming canon began with two interstitial entries, Javier Zamora’s “Unaccompanied” (2017) and Valeria Luiselli’s “Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions” (2017), both of which straddle the shift from the Obama to the Trump administrations. While Zamora’s collection begins with the day Obama was first elected, he also includes a poem “To President-Elect” — Zamora leaves him unnamed — that marks the recent regime change. Meanwhile, Luiselli’s book, preoccupied with the 2014 refugee crisis that saw an increase in unaccompanied minors from Central America coming to the United States, ends with a coda that describes the shock of a Trump presidency and the glimmers of hope she finds in groups advocating for immigrants’ rights. José Olivarez’s “Citizen Illegal,” published in 2018, similarly explores this tension between terror and hope. In the most direct reference to life under Trump, “I Walk into Every Room & Yell Where The Mexicans At,” he captures the anxiety that the speaker — and Latinxs as a whole — feel among ostensibly liberal white women who we all suspect actually voted for Trump.

The post-Trump canon flourished in 2019, with the publication of Natalie Scenters-Zapico’s “Lima :: Limón” and Carmen Giménez Smith’s “Be Recorder.” Scenters-Zapico includes a poem, “Notes on My Present: A Contrapuntal,” that is split in two. The poem on the left side of the page explores the violence of empire while the poem on the right concatenates Trump’s June 16, 2015, presidential announcement — in which he calls Mexicans rapists — along with other statements he’s made about Latinxs (though he calls us “Hispanics”). Finally, “Be Recorder” offers an extended meditation on what it means to be “American” and challenges the United States’s arrogance in assuming exclusive use of the term.

Jennine Capó Crucet’s essay collection “My Time Among the Whites” (2019) is a remarkable entry within this formidable body of work. While Capó Crucet and Luiselli share an interest in the essay form, their books could not be more different. Luiselli structures “Tell Me How It Ends” around an intake questionnaire for immigrants. The questions detail the arduous journey Central American children take to get to the United States and the legal challenges they face while here. But Luiselli also demonstrates how the questions fail to meaningfully capture immigrants’ experiences. Capó Crucet’s book, by contrast, is an interrogation of the American Dream, of American myths, and the whiteness that undergirds it all. “My Time Among the Whites” is also a thoughtful exploration of what it means to be a first-generation college student, a child of immigrants, and a professor to boot. While in “Tell Me How It Ends, Trump emerges at the end of the book, an addendum to what came before, in My Time Among the Whites,” his presence permeates the collection. More than that, the racism and white supremacist structures that led to his rise inform Capó Crucet’s exploration of what it means to be Latinx in the time of Trump.

Like Carmen Giménez Smith’s “Be Recorder, My Time Among the Whites” considers how Miss America/Miss USA reflect the American Dream. For Giménez Smith, Miss America emerges as a representative of the United States. For Jennine Capó Crucet, Miss USA, the pageant organization formerly owned by Trump, is intimately tied with her birth, as her parents named her after the 1980 Miss USA runner-up, Jineane Ford. As she explains, her parents “thought that giving their American child a distinctly ethnic name came with unfair, quantifiable consequences.” Thus her naming is not just an act of assimilation, but also of passing, an intentional decision to remove ethnic barriers to their child’s success. Yet, as she heartbreakingly explains, the innovative spelling her parents chose “always flags for certain people — people looking for it — as a marker of my parents’ immigrant status, their alterations betraying the reason they went with that name in the first place.” Even as she makes the distinction between the sound of her name and its spelling, her description of her parents imagined choices gently pokes fun of them and, more importantly, of the English language, demonstrating that ultimately, she is on their side: “[W]hat is that ah sound doing in there anyway?” she writes. And really, who wouldn’t agree?

Click here to read long excerpts from “My Time Among the Whites” at Google Books.

As Capó Crucet’s naming suggests, “My Time Among the Whites” explores the tension between immigrants’ culture and the American Dream, especially since, as the essays demonstrate so painfully, the American Dream wasn’t designed with immigrants (or people of color more generally) in mind. Growing up in Hialeah, the predominantly Cuban American city that she writes about in “How to Leave Hialeah” (2009), she reflects on the important role Disney World played in her life. As an adult, however, much of the magic of Disney is gone. What was once a site of pleasure becomes something more than a guilty pleasure — it becomes another site of analysis, another reinforcement of hegemonic beliefs. Describing her experience going to Disney World for her birthday, she observes, “During the days you spend in the parks, Disney will pretend you are white, American, cisgender, and straight, and everyone and everything around you will pander to and assert this understanding of the Disney fantasy.” The fantasy of Disney reveals itself to be a fantasy of whiteness, of privilege. This perhaps should not come as a surprise, but part of the magic of the Magic Kingdom is surely that one will not notice the differential treatment they receive inside and outside the park.

While such moments of analysis can take the reader out of the memoir-like moments of the book — and thus the illusion that we’re simply reading autobiographical stories — Capó Crucet’s analysis is exactly why “My Time Among the Whites” is vital reading for Trumpian times. As her collection demonstrates, these days the everyday aspects of growing up in the United States, of growing up American, all carry within them an overwhelming sense of foreboding. They underline our complicity, the ways we have internalized white supremacy and use it as a benchmark to measure our successes and failures.

Capó Crucet’s most extended meditation on Trump and immigration occurs in her most anxiety-producing chapter, “Going Cowboy.” There, she describes moving to Nebraska and signing up to learn how to herd cattle on a ranch. She describes how Fox News was the channel of choice in the rancher’s home, how the rancher rants “about Mexicans getting free passes into the United States.” This incident causes Capó Crucet to reflect on the rancher’s comment and point out:

[T]hat there is a Latinx group that, at the time, did benefit from that kind of special treatment. That privilege, which could be described as a free pass to citizenship, had been extended (for many years and for many complex reasons) to Cubans. Meaning, to my parents. The rancher had no idea that the manifestation of one of his greatest fears — the American-born child of these immigrants who were taking everything, everything — was sitting at his dinner table.

Here, she refers to the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act, which allowed any Cuban who entered US waters to apply for residency after living in the United States for a year (this policy was later revised in 1995 to only apply to dry land, thus the name “wet foot, dry foot”). In making this oblique reference, Capó Crucet emphasizes the asymmetrical privileges afforded to some immigrants over others, particularly from Latin America. Reading her words, “the American-born child of these immigrants who were taking everything, everything,” I couldn’t help but think about the cruel joke that makes her the manifestation of nativist fears: an associate professor, a successful writer, a person committed to her community. But of course, this is the actual fear — that immigrants and their children will be more successful than their white peers, demonstrating that having all the privileges and advantages in life does not make one successful. The fear is of excellence, not crime.

In moments like this, Capó Crucet’s clear-eyed examination of whiteness demonstrates that Trump isn’t what ails us; he’s the symptom, not the disease. This becomes particularly clear in her deft analysis of Latinxs’ conflicted relationship with whiteness — a relationship that demonstrates our complicity in the systems that oppress us. In Latin America and among Latinxs, lighter skin is still valued over darker skin, an idea expressed by the term “mejorar la raza” or “improve the race,” which generally refers to marrying someone with lighter skin to further whiten the subsequent children and thus, future generations. In “My Time Among the Whites,” Capó Crucet explores what it means to “a kind of white” as well as “to realize that I was not white.” In her telling, her whiteness reveals itself in moments of privilege: when she doesn’t consider demographic information in making a decision, when she doesn’t immediately realize that an all-white space may not be a safe one.

The moments when the differences between Cuban American whiteness and white American whiteness come up span a range of experiences, from having to explain why she won’t get a sunburn on her ears to learning that dancing is a dead giveaway for her Latinx roots. Yet, even as she discusses the elision between the American Dream and whiteness — through her name, through Disney World, through light skin — Capó Crucet carefully points out that Cuban American whiteness is an illusion of whiteness, at least in this America. Of the 2016 election, she remarks, of her parents and their generation,

They didn’t realize that not voting — the ultimate gesture of complacency — was a privilege they didn’t actually have: It only felt that way because they lived in Miami, a place where it was easy to think, if you were Cuban, that you were white and therefore not part of the immigrant groups Trump was making a campaign out of promising to deport.

As she notes above and as all Latinxs know: When Trump and other white supremacists name a specific Latinx group, they really mean all of us. It doesn’t matter if the group is Mexican or Guatemalan, citizen or non-citizen, criminal or non-criminal — when Trump refers to any of us, he refers to all of us.

In “My Time Among the Whites,” and in what I’m calling post-Trump Latinx literature, the 2016 election emerges as a flashpoint that highlights, on the one hand, the specific complicity between Latinxs and white supremacy, and, on the other hand, how Latinx authors are building a resistance canon. According to The New York Times, 29 percent of Latinxs voted for Trump. While that might not seem like much, especially considering that 27 percent of Latinxs voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, it is surprising because Trump built his platform on explicitly anti-Latinx policies. As Capó Crucet points out, many Latinxs didn’t vote at all; as I can attest, some of us have family members who did vote, but voted for Trump. Within these complex dynamics, “My Time Among the Whites” emerges as a salve. It incisively traces the ideologies that led to Trump, such as the American Dream, and indicts our adherence to these ideologies, many of which are deeply internalized. None of us are blameless, but when Capó Crucet writes, of predominantly white campuses, “[t]his place never imagined you here, and your exclusion was a fundamental premise in its initial design,” she’s also writing about the United States writ large. We may always be among the whites, but as post-Trump Latinx literature demonstrates, we can resist a world that privileges whiteness. And we must use the time while we still have it.

Renee Hudson is an assistant professor of Latinx literature in the English department and an affiliated faculty member in the Latino Studies Program at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

This review originally appeared on the Los Angeles Review of Books.

The Solution to Homelessness Is Staring Us in the Face

It’s no secret that homelessness in the United States, especially in California, has reached critical levels. That the wealthiest state in the wealthiest nation in the world is dealing with a crisis that stems so clearly from inequality and neglect should have its predominantly left-leaning residents up in arms. And to some extent, they are.

Becky Dennison, executive director of Venice Community Housing in Los Angeles, who speaks with Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer in the latest installment of “Scheer Intelligence,” has dedicated her life’s work to helping address homelessness, refusing to give up fighting for the well-being of her less fortunate neighbors against all odds.

“It’s urgent work; it’s necessary work,” Dennison, a former mechanical engineer, tells Scheer. “It is, I think, one of the social justice and civil rights issues of our time. And so I want to be a part of that solution.”

Related Articles

Could This Be the Humane Housing Policy We’ve Been Waiting For?

by Clara Romeo

Thousands of Children Will Be Made Homeless Under Trump's New Plan

by

Venice Community Housing houses 500 people and plays a crucial part in helping put roofs over the heads of those who most need it. Dennison’s motivation is her belief that housing is a human right and is, without a doubt, the solution to homelessness. Not everyone in her community feels the same way, though some do, but with a big caveat: They want affordable housing projects to be placed far from their own homes. This phenomenon has become known as Nimbyism—NIMBY being an acronym for “not in my backyard.” Dennison has a different term for it: housing segregation.

As Dennison and Scheer conclude during their discussion, the issue of homelessness is intersectional, stemming from both class and racial divides.

“One thing we’ve never really considered in America in a serious way since the Great Depression are class divisions,” Scheer says. “And we always assumed—even in the Great Depression—we assumed it was temporary. People had fallen upon hard times, and so forth. But we are increasingly in a class-divided America.”

“This is a class issue,” Dennison agrees, adding, “it is also an issue of institutional racism. The overrepresentation of African Americans in the homeless community in Los Angeles is beyond compare.”

Listen to the full discussion between Dennison and Scheer as they grapple with one of the most pressing crises the U.S. faces today, tracing its roots as well as identifying hope for a better future. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Introduction by Natasha Hakimi Zapata

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence,” where I hasten to say the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case it’s Becky Dennison. And my hat’s off to you, because you do this work that a lot of people walk around, pass the homeless in many neighborhoods in L.A., but other cities; they say, somebody should do something about this, you know. And if they have a religious background, they’ve read Luke and know that the parable of the Good Samaritan–we’re supposed to stop, see who’s living in this tent or on the floor, are they alive, dead, minister to their needs, and we’ll get into heaven, hopefully. But we don’t [anything] about it, we put it out of sight, out of mind and all that. And you are, you were a mechanical engineer, which clearly it was a path to a good, solid career, OK.

Becky Dennison: Yes.

RS: And what you’ve been doing since you left, I guess, the University of Minnesota–

BD: Yep.

RS: Is, ah, not a solid career. You decided back in 1992–you’d come to Los Angeles, I gather–you were going to do something about this refuge–ah, refuse of people, indistinguishable from garbage bins and everything else, on the streets. Now we have many more people on the streets; the statistics are compelling. And you’ve spent a lot of time, and up until about three years ago you were actually working in the inner city, downtown and all that. And now you work with the Venice Community Housing program, which houses, I don’t know, 190, 200 people or something–

BD: About 500 people. About 200 units, yeah.

RS: Five hundred people. Oh, and 190 units. But you’re out there now in a community, Venice, which is close to the ocean; it’s undergoing gentrification. And it’s going to go the way of Beverly Hills, or certainly Santa Monica. And you’re there telling people, no, we don’t want to just warehouse, or–not even warehouse, there aren’t warehouses for them–put them in the streets of downtown L.A. No, they should be here and elsewhere in decent housing. So what brought you to this point? And how come you’re not more depressed? You seem quite cheerful.

BD: [Laughs] Well, it’s not depressing work. It’s urgent work; it’s necessary work. It’s, I think, one of the social justice and civil rights issues of our time. And so I want to be a part of that solution. I came to the work doing some volunteer work in Skid Row, and meeting some of the residents there, and decided to leave my engineering job to do this work solely because of the energy and the resilience of the folks living in the community. People who have experienced homelessness, people who are extremely low-income, and really their fight for their lives and their communities. And I just feel like Los Angeles is a city that can and must do so much better in terms of equity and in terms of housing for all.

And so yeah, it doesn’t–it doesn’t, ah–it’s frustrating, and it’s angering, the lack of action and lack of urgency in this country for the issue for a very long time, and particularly in this city. But we have been able to take steps forward, and that’s what keeps us moving. And again, we can’t leave folks in our streets and sidewalks in these conditions. We can’t leave folks outside to die. And Venice Community Housing has been doing that for 30 years, and it was a perfect match for me to join that organization, because affordable housing is the solution to homelessness. And there are other issues that folks face, but fundamentally, people need a place to live; people deserve a place to live. And Venice has long been a diverse community that has been welcoming and inclusive, and we are going to fight to keep it that way.

RS: OK. Now, for people who are not from Los Angeles, they should understand first of all, even though we are the capital of the world, our official propaganda–we obviously are a very attractive city to people all over the world; we’re a center of culture, control exports to the rest of the world, a way of dignifying or celebrating the American way of life. But Los Angeles, I think, has the most pronounced problem of homelessness in the country.

BD: We do.

RS: And you can’t ignore it. We’re doing this program from the University of Southern California, which is 37 blocks from City Hall. And we have homeless people all around here; you go over to the Shrine, where they used to do the Academy Awards; you go anywhere a half block off campus, and there are people, humps of humanity in hallways, in the street, sleeping there and so forth. And unfortunately, it’s good for our school to be here so at least there’s a visibility, but it also leads to a certain cynicism. Who are these people that are homeless and in these conditions?

There are two myths about it. And when I interviewed the head of the United Way, which does very good work here, he dispelled two myths. One is they come from elsewhere; we have this good climate and therefore they leave Pennsylvania or New York and come here. He said that’s not really true; 70 percent of our homeless people were housed previously. They’ve fallen upon hard times; housing is expensive, and they don’t make enough money to be able to get housing. The other has to do with mental illness, and California was the scene of a great experiment, which unfortunately a number of civil libertarians, the ACLU joined with right-wingers like Ronald Reagan.

And there was an idea that people could somehow take their meds on the fly; there was the Lanterman-Petris Act. And that we didn’t want mental institutions and so forth. So another myth is somehow now we have these mentally ill people and they end up on the streets. And I’ve seen comments that you’ve made that you would agree with the United Way’s position, that this is a myth, it’s a way of alienating us from these people–OK, they’re mentally ill, or they’re from somewhere else–no. They are, in fact, us.

BD: Yeah. That’s exactly right. And it’s not to say that there aren’t always a handful of folks who have come from other places, and especially young folks who come for the sort of L.A. dream. But most people are from our communities right here in Los Angeles. And there is a mental health crisis in the nation, and within the homeless community. But it is not the entirety of the homeless community. And it really is that it’s a way of othering and creating a fear of people. And there’s no reason to be afraid of people with mental illness, either.

Actually, they’re much more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators of crime. But it is a way of saying–I think to some extent it’s a human condition to say “That could never happen to me.” And it’s a way of also placing blame on individuals, when really the issue is a structural issue, and this drastic lack of investment in affordable housing–which is also Ronald Reagan’s claim to fame, when he was president and cut the HUD budget by 80 percent, and it’s never been restored since then.

RS: You know, it’s interesting. I interviewed Ronald Reagan before he was governor and before he was president. And I got to know the guy. And he himself would have been homeless as a child were it not for the New Deal programs. And his father actually had a job with the New Deal. And I reminisced with him about that, how much the government did for people who needed homes and housing and jobs and so forth. And I remember my own father would take me down to the Bowery in New York, and show me the people there lining up for food and stuff.

And he himself knew he was one paycheck–if he got laid off–which he did; he actually got fired the day I was born, and it took years to get a job back. But it was always, he always would tell me: These people are us. And you should worry about them, and you should also work hard so you don’t end up that way. But the system is rigged. We have a depression, we have lost jobs, and so forth. We have lost that, in some sense.

And I want to bring you to where you are now in Venice, Calif.. And this is a hip, deep blue, progressive community, Venice. As is Santa Monica. And these communities have experienced gentrification, and they’ve actually developed quite a bit of hostility towards less fortunate people in their midst. And you’re up against it, because you’re trying now to develop affordable housing in Venice. And this is a story throughout the country, OK? And then there’s resentment: “Why are you feeding them, and why are you going there?” But then– “Bring them here, housing? Why are you doing that?” So tell me about the battle in Venice. Because I suspect a number of people listening to this might be torn in the same way. They want to do something for the homeless, but they don’t want to do it in their neighborhood–the NIMBYism.

BD: Yep, yep. So I do want to say that–well, so we are building in Venice for the first time to build up 100 percent affordable housing developments, and supportive housing developments, for the first time in 20 years in Venice. So there’s been a long dearth of development there. And we are facing some really significant battles. But I do want to say that the large majority of people that we talk to in Venice, and throughout the city, actually support what we do, and support what we do in their neighborhood. And they’ve kind of, there’s polling that shows that there’s this silent majority that wants these solutions in their neighborhood–

RS: Oh, I can back that up, because you’ve had Proposition HH, is it? And H?

BD: Yep, and HHH.

RS: And on the county level–and just to defend L.A. County and L.A. City [Laughter]–no, the fact is the voters here did vote for some billions of dollars for affordable housing. However, the contradiction is, the idea is to put some of these services and housing in every councilman’s district; that’s where they have found the resistance.

BD: No, for sure. And we have faced really incredible and, in some cases, very ugly and hateful resistance to what we’re doing in Venice. And you know, people have said, you know, “We don’t want these people here,” and so using kind of the same thing we were talking about, that somehow these folks are not from our communities, that don’t deserve our care and love. That everybody should live east of Lincoln, which is kind of one of the borders of the coastal zone. And actually in a community meeting I said, you know, we don’t support everyone living east of the 405 or east of Lincoln, because that’s a housing segregation argument, and we’re not about housing segregation.

And a woman said, “Well, I am.” So there are–there are a minority of voices that are adamantly opposed to anything happening in their neighborhood. And we just believe that it’s our goal to mobilize all the folks that are supportive, because really, it’s not that much different than any other housing segregation movement we’ve seen over time. In terms of who deserves to live where, and how do you zone property, and who has the voice–wealthy homeowners have the loudest and strongest voice. And we’re dead set on overcoming that.

RS: So this woman that said we want to have this segregation–did you talk to her?

BD: I have talked to her quite a bit, yes.

RS: And what is her defense?

BD: I mean, I don’t think there is a defense for that argument. But sometimes she and others have said, you know, “I’ve worked really hard to get this property by the beach, and so everyone else should have to work hard.” I remind them that Venice and all, you know, tourist towns have a lot of hard workers making $15 an hour who are never going to afford to live in Los Angeles, and they deserve housing too; they’re working hard. And folks who are experiencing homelessness sometimes are also working hard, or have certainly worked throughout their lives. And that, you know, at some point we cannot–these are the same folks who complain about homeless folks being on their sidewalks.

And no one is going to disappear from space. And so no matter your feelings about homeless folks, whether you’re coming from a space of compassion and care or not, housing is the solution, and people have to embrace that solution. It will make the entirety of the community better and healthier.

RS: Well, if you don’t, it’s going to destroy your community. I saw a quote from you in which you said housing is a human right.

BD: Yes.

RS: And I think there’s a very–look, you know, you can’t get any [Laughs]–I don’t know why I’m giggling, we’re talking about tragedy here. But the fact of the matter is, you can’t get any basic, more basic, than having a shelter and food. You know, come on, safety; every society has at least paid lip service to this. And it’s a very interesting notion of privilege. As somebody who lives downtown, I resent that person in Venice, because they’re all for feeding the homeless downtown–they might even contribute money to it–where I live.

And they’re all for, you know, shelters there and services there, and so forth. But not–you know, this is the NIMBYism that we’ve talked about. And it’s interesting, because first of all, this idea that–who gets to live by the water, or the beach–the California Constitution guarantees all of us access to the ocean.

BD: That’s right.

RS: It’s one of the enlightened things about it. And so this whole idea of privileged communities, and that you get to pick it–and so money talks.

BD: Yep.

RS: Now, that would be fine if you find some stuffy, old-fashioned republican, right? Or so forth. But we’re talking about Venice! For people who don’t know who are listening to this, who maybe live in, you know, I don’t know where, some other place, you know–Venice was the hip community. Venice was where the Beatniks were. Venice is where, you know, people hang out and dress all kinds of different ways and listen to all kinds of music. So actually, they want diversity and excitement without poor people.

BD: Yeah, that’s right. And what’s really frustrating is most people will tell you that they moved to Venice, as opposed to another beach community, because of the diversity, because of the artists, because of the funky nature. But when it’s taking steps to actually restore some of that diversity that’s been lost in the pushout in Venice, then people are opposed. And it’s just, it’s not logical, it’s not fair; it’s just not acceptable.

RS: But also what’s key to it is who are our fellow humans. Because this objectification is to say, oh, they’re crazy. Or they’re dangerous, or they’re worthless, or they didn’t want to work, or what have you. And this is a way of dismissing humanity, right? I mean, yet if you know anyone–because you do; many of us have had cousins, or nephews, or our own children, or you know, somebody end up in that situation–then suddenly oh, no, they’re real people, that’s my cousin Louie, you know. No, and he just fell upon hard times, and I would like to help him, but it’s not easy, and so forth. And it’s interesting, because this whole notion of privilege has become acceptable. And I really, here at–and I’m not going to put down the University of Southern California, where we’re doing this; I’m not, because I think as a school we probably do as much as any other institution to reach out in the neighborhood, to work with people.

We have a homeless project here, I think our students work in the local schools, they work in the neighborhood. So I think we’re just as good as, you know, Stanford–which, of course, is in a privileged area to begin with–or UCLA, which is in a much more privileged part of town. I’m not going to trash USC, but something I’ve noticed happens is “us-them.” And we have a daily crime report, whoever’s committing a crime. And there’s a sense of danger about the larger community. As you point out, if you walk–you know, because I go home from here through Skid Row quite often. And you know, you stop there, you fear for them! Not for yourself. I mean, who’s protecting? You see women, you see children.

And if you have any kind of decency, you’re not going to worry about yourself primarily; you’ll say wait a minute, this is a hell of a circumstance, you know? And you know where that came home to me, was during the Occupy Movement. And I know I can ramble a little in these interviews, but it kind of clicks. And I remember that the night that they destroyed Occupy in L.A., I went down there and everything; it was terrible–

BD: Yeah, I was there.

RS: They put up barriers, and I don’t know if you were there that night–

BD: Yeah.

RS: –but it was just awful. And the big argument that I heard–so I stayed all night, and then in the morning people came to work at City Hall in the state building, federal building. And they were saying–“Oh, it’s about time, and they should have cleaned it up, it was a mess, and there was dirt, and you know, people were defecating, and there was crime,” and so forth. And I had spent that night sort of wandering up and down that mile or more, two miles of intense poverty called Skid Row. That they never noticed. It was the visibility. And that’s really what bothers people in Venice or Santa Monica or Beverly–well, Beverly Hills they don’t allow it, they just arrest everybody. But it’s the visibility. That’s what’s irritating, right?

BD: Yeah. No, it’s beyond irritating. That’s what’s angering, is that people–the solution is just not here, get people out of my eyesight. And that is about people feeling comfortable and privileged to not have to see what this system has done to people experiencing extreme poverty. It’s a comfort level and a privilege that people are demanding, that we can’t accept, because we live in this city and we collectively are responsible to solve these issues. And it is–you know, even for folks who have maybe a friend or a family member, or who have befriended somebody, or you know, certainly more and more people are facing eviction and being pushed into homelessness for the first time.

But it doesn’t always change the mindset of “I care about that, and I want to do something, but I don’t want to have to be experiencing it every day, and I certainly don’t want to solve it here in my neighborhood.” And those, again, it’s a minority of voices, but they win a lot. And we just can’t accept that, and that’s why we see the continual policing of homelessness, and sort of pushing. And even in Skid Row, which is an amazing community in many, many ways, but it also was built on a policy of containment. So that the new downtown–

RS: Oh, and dumping people, and letting them out from hospitals and so forth. Let me ask you a question. How do we bottle you?

BD: [Laughs]

RS: No, really. I mean, you seem so sensible. And you know, you had a lot of–you have other possibilities in life. You could wake up in the morning and say, hey, I’ve paid my dues, I’m not going to do this anymore. There’s an excellent movie–I thought excellent, anyway–The Advocates. I don’t know if you’ve seen that.

BD: Yes.

RS: Yeah, and about working with the homeless, and these people actually look into the tent, who’s there, are they alive, or–you know, and then you can’t ignore, this is a human being. You know, and different gender and age, and come in all shapes and sizes. And you can’t just ignore ‘em. So this ability to ignore the other, the reason I find it so depressing is this is going to be more and more the norm in this society. Because one thing we’ve never really considered in America in a serious way since the Great Depression are class divisions.

BD: Yeah.

RS: And we always assumed, even in the Great Depression, we assumed it was temporary. People had fallen upon hard times, and so forth. But we are increasingly in a class-divided America. Sharp division. We know since 1992, when Bill Clinton–the years we’re supposed to love the democrats, OK, I’m not going to cause more hostility out there. But the fact of the matter is, somewhere at the end, you know, it wasn’t just Reagan, but–

BD: Oh, absolutely.

RS: Actually, you can trace it from Bill Clinton on, we’ve had this sharp division. More and more people, even if they work very hard–I shouldn’t say “even,” when they work very hard–can’t afford housing in many places, most places. And you know, so poverty is not a mental health problem. It may cause mental health problems, because it’s a hell of a thing to sleep on the street. But the fact of the matter is, this is a reality of modern capitalism.

BD: Yes.

RS: And so I want to ask you, why are you hopeful about being–why–OK, why have you made this choice? And you’ve been doing this now for what, ‘92, ‘02–you’ve been doing this, what, for eighteen–

BD: Twenty-five years.

RS: Twenty-five years. And how do you keep going, and why do you keep going?

BD: Well, so I do think there is hope to upset the capitalist system. It’s certainly been done in other places, and it’s been done in pieces here. And so it’s certainly not going to happen if we don’t fight for it. And until that happens, I just feel strongly that we can and must do better for those folks who have been pushed out. And this is a class issue; it is also an issue of institutional racism. The overrepresentation of African Americans in the homeless community in Los Angeles is beyond compare. So those two–

RS: Do you have statistics on that?

BD: I don’t know them off the top of my head, but I think it’s an overrepresentation of something like 20 or 30 times. Yeah.

RS: Yeah, because we don’t have a very large black population in California anymore, because we had the forcing out of the very jobs that black people had come to do–

BD: But at one point, a few years ago, one out of about 250 white and Latino residents were homeless, and one out of 18 African Americans were homeless.

RS: Yeah, that’s a startling statistic–and you can eyeball it very clearly without doing the survey. And it’s an increasing population. I think in Venice you’ve even had an increase of, or in the west side of L.A., 19 percent?

BD: Yep.

RS: In, what, the last year or something?

BD: Yeah, 12 percent I think. But overall, larger than that, yeah. But I mean, that’s why you have to sort of balance hope and anger and indignation, right? Because we are making progress here and there. And every single person we house matters, right? And so with the passage of the ballot initiatives, we have to make sure we maximize the impact of those things. And then we have to fight for more and more and more.

RS: OK, but–but let’s cut to the chase here. This is not an individual problem.

BD: No.

RS: This is not a case of people fell off the wagon here because they started drinking or they got drugs or they lost their mind for one reason or another.

BD: No, this is a structural problem. This is the, this is the–

RS: Because that’s the cop-out that’s always offered. And that was the mistake, you know, of the Reagan-ACLU alliance; they said, oh, we’ll give people drugs, there’s a pill and that’ll solve it. No, you have to have decent jobs, you have to have decent conditions. And even, the very idea of housing–it’s funny, I saw an interview with you where somebody in the audience, or somebody brought up the Chicago housing project–

BD: Oh, yeah. They like to say we’re building Cabrini-Green in Venice. Yeah.

RS: And it’s interesting, because I grew up in an area in New York where housing projects came in, and they actually were a good thing. You know, because they–you know, and a number of them survived quite well over the years, you know. And the fact of the matter is, they weren’t perfect, but you weren’t out in the street, you know, in the rain and the snow and all that. And people could go to school, kids could go to school; they could be raised, and so forth. And what happened was, you had a concerted effort to attack every single program that would benefit these folks.

BD: That’s right. I mean, public housing is the reason why the homelessness in the Depression era was temporary. Because there was a massive investment in housing, which obviously makes sense. So we–

RS: Yeah. Including the GI Bill, which everybody forgets.

BD: Yeah. And there were some, obviously, some racist issues with those housing programs. But–

RS: And by the way, to mention the Chicago project, there was also deliberate underfunding and abandonment of those projects.

BD: Well, that’s exactly what happened, right. So it was a solution that absolutely worked, and people call it a failure; it’s absolutely not a failed model. It failed its residents because of the disinvestment. They just pulled all the money out of that, and you couldn’t operate the housing in the way that you should. It was intentional, to create slum housing, to then say, oh, this program failed, let’s get rid of this housing–and, by the way, all the people in it, en masse across the country. And that was largely under Bill Clinton. Certainly started before.

RS: OK, well, so long as we’ve brought old Bill back into this [Laughter]. Let me get back to the cutting edge of this politics. Because one of the convenient things would be to blame it all on–in a community like this here, in L.A.–on Trump. And blame it on mean-spirited republicans. And they certainly have done their share of damage; I’m not trying to get them off the hook here. But the fact of the matter is, it was Bill Clinton who ended the federal poverty program, so-called welfare reform.

And he had this idea, people should learn to fend for themselves, and blah blah blah. But he didn’t worry about what kind of jobs they would have, and so forth. And you have a lot of undocumented labor, and that, you know–OK, great, we don’t want to deport people, but on the other hand we won’t guarantee they have decent working conditions, they’re paid real wages and so forth. And you’re really, in Venice, up against liberal hypocrisy.

BD: Yes.

RS: So why–let’s not beat around the bush here. These people are, what, frauds. Frauds. I mean, come on. You know, you talk a good game about human rights and everything else, and you step around someone–I do it myself, by the way. Let me admit to being a hypocrite, OK. I mean, I do step around people when I’m going here, and I’m in a hurry to get something in the store, and I want to go–and besides, I don’t want to get involved every minute, I have to force myself, I have to reread Luke and the Good Samaritan. I teach that here in the ethics class. It’s a compelling injunction, you know; because remember, in the Good Samaritan, the lawyer says to Jesus, you know, how do I get to heaven? And Jesus tells this story of two, the rabbi and the other one from the tribe, they pass by this person who’s been beaten.

And then the Good Samaritan, who’s from another tribe–the other–comes and, you know, he takes this person, puts him on a donkey, takes him to an inn, and says I will come back and see how he’s doing. Well, that’s taking care of the homeless. That’s taking care of that person in the street. Well, I have–I don’t know anybody in my circle of friends, or people I associate, that will really–except under very exceptional circumstance–stop to do what the people did in that move, The Advocates. Figure out who’s there on the street; are they even alive or dead. I go by people here around USC all the time–I don’t know whether they’re alive or dead. And I don’t stop and engage them. And so this is a problem not just of human rights, but of what is humanity?

BD: Yeah.

RS: Right, in a major city, that we accept.

BD: Well, I think that’s the issue, right? It’s become commonplace. People say all the time that it’s an intractable, insolvable problem; that’s not true. And so it becomes easy for folks–all of us, myself sometimes–to accept that that’s the way Los Angeles is, and move forward with your day. And again, though, when the solutions come forward, then you would expect at least people to embrace the work that other people are willing to do to solve the problem. And I think that’s an issue we have to get past.

RS: I’m not just–

BD: Though I do have to say, again–large majority of people are supportive. And if we had those folks organized and speaking out, it would help the issue as well.

RS: Right. And I–this is not false optimism. I mean, I was blown away that a majority of voters in L.A.–city of L.A., but also the county; that includes Beverly Hills and other places–did vote for substantial funding for homeless people. However, they don’t want it in their community.

BD: Many. You’re right.

RS: And that is, you know, the real disconnect here. It’s–because forget about just its–the immorality of being indifferent to the suffering of others. It means that you yourself have become so tribal, so personal, that the people you care about are only the people that are in your family, your social circle, your clan, or what have you. Then you will reach out. You know, and it’s interesting, I have these statistics from the Federal Reserve that a very large number of people in this country live paycheck to paycheck. OK, well, if that paycheck dries up, and you don’t have family, and you don’t have savings–which most of these people don’t; that’s what it means to live from paycheck to paycheck–what are you going to be other than homeless?

BD: Right. That’s why we see the homeless community growing in Los Angeles. Because more people are falling into homelessness for those reasons, every day, than we can possibly move into housing. And those are the structural gaps and the class issue that you’re talking about, that has never been addressed in the last 50 or 60 years by a politician of any background.

RS: Well. So what’s going to happen now? I mean, our mayor–right, Garcetti, who was going to run for president, but this reality sort of haunted him–right?

BD: Yeah.

RS: You know, people were–wait a minute, clean up your own town. Ah, what–really, I mean, what’s going to keep you going? Are you going to burn out?

BD: No, I’m not going to burn out.

RS: So what are the successes? Tell me a good say.

BD: So, I mean, a great day is–you know, today, for example, there’s an organized group of folks who are trying to protect the rights of folks living on our streets, because there’s nowhere else for people to go. And we’ve gotten to a place where the City of L.A. may need to rescind their law that makes it illegal to sit or sleep on the sidewalk, even though they’re short tens of thousands of shelter and housing beds. That’s a long fight that people have been in. A good day is when, you know–and it isn’t about one person, but it is a great day when one person moves off the streets into a house that we have, that we operate in Venice. Because that is life-changing and community-changing. It’s a great day when we had our Rose Apartments approved for–we’re going to break ground in January on 35 new homes in Venice, again for the first time in 20 years.

RS: Is that on the lot that’s contested?

BD: No. And then another great day is when we hear from folks like last night at a community meeting, entirely 100 percent consensus in support for us building on the city-owned parking lot in Venice that in the news media you just only hear sort of the hate. And the hate is very strong. But a lot of folks sitting in rooms saying, how do we win, how do we get this done? Because if we lose here, we lose ongoing. And so those are the things. People are down for the fight, and we’ve got a long ways to go, and some things we can do person-by-person, but we’re always looking at the structural issues.

RS: You know, I just have a political angle here, a gimmick. It’s interesting, because we say Donald Trump is defined by the crowd at the county fair or something–wherever he is–that is cheering his more hateful message, you know, the us and the them, and basically informed by racism, which the homeless issue is, and the other, and so forth. Why don’t we have a test for democratic candidates to come to your area–forget about downtown Skid Row, that would be a good place–but come to Venice. To their political base of liberal–why don’t you invite them? I’ll give you an idea. Seriously, a candidates’ forum. So Kamala Harris can be there, and Bernie Sanders can be there, right? You know, and all of them can be there: do you support housing here on this vacant city lot for homeless people?

BD: I love it.

RS: That would be–that would be a great test. Elizabeth Warren, who I have great respect for–OK. But right here. Will you tell the local folks here why this is good for their community? And then do the same thing next to the Salesforce building in San Francisco. If you go to downtown San Francisco, the highest building there now, Salesforce building–surrounded by homeless people at night. You have to pick over them to walk from your restaurant or bar, you know, trendy bar, to get to your car or something. That’s where the candidates should go.

Because I think–would be nice if it was also a good test for the republican base, but it would be a very good test for the democratic base. You claim you care about the other; what about this issue of gentrification? Because one could argue–and I’m putting myself in the group; before we were talking about this subject, I was chatting with you.

I’ve lived off and on in downtown L.A. since 1976, when I came to work for the L.A. Times. And I did that because I’m from New York, you know, and I thought hey, I’ll live where I work. But I couldn’t buy a bottle of milk. And there was no amenities, and then we had a child, and we had to go four miles to get groceries and so forth, or go to a liquor store. So at first I thought gentrification was a pretty good thing; at least it makes poverty visible, at least we’ll demand more services, more policing, cleaner streets and so forth. But then you realize gentrification is ethnic cleansing.

BD: Yes.

RS: And it’s evil. You know, and it’s gated communities, it’s privilege, it’s zones of protection from the other. And it’s a way of becoming cynical. So I want to end on this final point. The reason I wanted to bottle your attitude or energy–how do we defeat cynicism? What prevents you–well, this is the–here, I’m teaching at this school and everything. How do we–you know, and I’m still doing this, and I’m pretty old. So I clearly have found some ways of getting my passion going. But seriously, you know, you’re getting older too, right?

BD: Yes. [Laughs] Yes, I am.

RS: Not quite as old as I am, but you have, you know, maybe I guess you’re half my age or something, I don’t know. [Laughter] But anyway, seriously, what is your message? Say a young person wants to come and volunteer with your group, right. You have openings, right? Are they unpaid or paid internships?

BD: Both.

RS: Yeah, I’m against unpaid internships. [Laughter] But paid is good. So what’s your message, though? And how do you get them to come in for the long haul?

BD: I mean, that’s a hard question. But I do think that the message is that, you know, in every battle, in every fight against gentrification, in every fight against racism, there have been times when it felt like there was no win in sight. And we have seen gigantic social change in this country, and you never know at what point you are fighting in that battle. And so you better be in the battle. Like, you don’t want to be the person looking back at history and saying that you were apathetic, or you were the one excluding. There’s always a way to get involved on the right side in your local community, at the state level, at the national level.

And it is an urgent need. It is an urgent demand. It is an obligation of us, of being part of a community, to stay involved. And again, always, in the privilege seat–which you and I are in–you better not be more tired and more cynical than the folks who are in the most oppressed situation. If you can’t stand up next to folks who are in much worse situations because you’re too tired or you’re too cynical, that’s just not acceptable. We can do better than that.

RS: Well, let me push it a little further. I also think it’s clearly the way to give meaning to one’s life. And we shouldn’t be embarrassed to say that. We know that when it happens to one of our relatives. When they have trouble, when they lose their job, when they lose their way, they lose their mind, lose their health. Then we know that that’s–if we help them, that’s our best moment, it’s our most rewarding. The problem is, we don’t feel that way often enough about the so-called other.

We dehumanize them. The media helps us dehumanize them by just showing the danger or the–I remember, I worked at the L.A. Times, they had a series on the marauders. This goes back to Bill Clinton’s crime campaign, and you have this idea of these aliens coming out of South Central L.A. and invading all these otherwise wonderful communities, you know. But the fact of the matter is–and again, people should watch The Advocate. Or how do they work with you? Just show up at Venice community–

BD: Yes, absolutely, they can find us online, it’s easy to connect with us.

RS: OK. And the fact of the matter is, it informs your life at every level to do this kind of work. And if you don’t do it, it’s all just talk. Right?

BD: Yeah.

RS: So the final takeaway, we’re going to invite–you’re going to invite, I can’t get too political here. But you’re going to invite all these candidates to show up?

BD: We’ll give it our best shot.

RS: No, but I mean, wouldn’t that be as good a test–as good a single test of where they’re really coming from.

BD: Yep.

RS: Everything else is kind of fuzzy abstraction. OK. That’s it for this edition of “Scheer Intelligence.” Our producer is Joshua Scheer, who’s arranged all this. And Sebastian Grubaugh, the brilliant engineer producer here at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. See you next week for another edition of “Scheer Intelligence.”

Taliban Negotiators Go to Moscow After Trump Declares Talks ‘Dead’

MOSCOW—A negotiating team from the Taliban arrived Friday in Russia, a representative said, just days after U.S. President Donald Trump declared dead a deal with the insurgent group in Afghanistan.

Russian state news agency Tass cited the Taliban’s Qatar-based spokesman Suhail Shaheen as saying the delegation had held consultations with Zamir Kabulov, President Vladimir Putin’s envoy for Afghanistan.

The visit also was confirmed to The Associated Press by a Taliban official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to reporters.

It was the Taliban’s first international visit following the collapse of talks with Washington. The team was being led by Mullah Sher Mohammad Stanikzai.

In a weekend tweet, Trump had called off negotiations and canceled a meeting he said he wanted to have with Afghan government leaders and the Taliban at the Camp David presidential retreat.

Related Articles

#NeverForget the War in Afghanistan

by Sonali Kolhatkar

Afghanistan May Never Recover From the U.S. Invasion

by

The Myth America Tells Itself About Afghanistan

by Maj. Danny Sjursen

Moscow has been accused of aiding the Taliban as a safeguard against a burgeoning Islamic State affiliate that has close ties to the Islamic Movement of Afghanistan, a militant group in Central Asia. Russia has stepped up its defenses in Central Asia and has claimed thousands of IS fighters were in northern Afghanistan.

Moscow has twice this year hosted meetings between the Taliban and prominent Afghan personalities.

Shaheen told the Taliban’s official site on Tuesday that the group was still communicating with U.S. negotiators, at least to find out what to do next.

Washington’s peace envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has focused his efforts on regional players almost as much as on the Taliban and Afghan government interlocutors. Earlier this year, the U.S. released a statement signed by the U.S., China and Russia supporting Khalilzad’s peace efforts that called not just for an agreement on U.S. and NATO troop withdrawal and Taliban anti-terrorism guarantees but also a promise for intra-Afghan talks in which Afghans would decide the fate of their country as well as the terms of a cease-fire.

___

Gannon reported from Islamabad, Pakistan.

Ralph Nader: Trump Learned His Tricks From Corporate America

For avalanche-level lying, deceiving, and misleading, mega-mimic Donald Trump need look no further than the history of the corporate advertising industry and the firms that pay them.

Dissembling is so deeply ingrained in commercial culture that the Federal Trade Commission and the courts don’t challenge exaggerated general claims that they call “puffery.”

Serious corporate deception is a common sales technique. At times it cost consumers more than dollars. It has led to major illness and loss of life.

Take the tobacco industry which used to sell its products in the context of health and facilitating mental concentration. Healthy movie stars and athletes were featured in print and on TV until 1970.

Despite studies showing that sugary soft drinks can damage health, increase obesity, and reduce life expectancy, the industry’s ads still feature healthy, fit families in joyous situations guzzling pop. Fortunately, drinking water has regained its first place position as the most consumed liquid in the U.S.

Related Articles

Corporate Opportunism Has Reached a New Low

by

Corporations Are Waging All-Out Class War

by

Whether it is the auto industry’s false inflation of fuel efficiency or the e-cigarette companies deceiving youngsters about vaping, or the food industry selling sugary junk cereals as nutrition for children, or the credit banking companies misleading on interest rates, truth in advertising is oxymoronic.

To counter these “fake ads,” the consumer movement pushed for mandatory labeling on food and other products. The Federal Trade Commission is a chief enforcer against deception in advertising, but it has waxed and waned over the decades. The FTC describes its duties to protect consumers from unfair or deceptive acts or practices as follows:

“In advertising and marketing, the law requires that objective claims be truthful and substantiated. The FTC does not pursue subjective claims or puffery — claims like “this is the best hairspray in the world.” But if there is an objective component to the claim — such as “more consumers prefer our hairspray to any other” or “our hairspray lasts longer than the most popular brands” — then you need to be sure that the claim is not deceptive and that you have adequate substantiation before you make the claim.”

A few times, companies, caught engaging in false advertising, were compelled by the FTC to announce the correction in their forthcoming ads and apologize. Those days are long gone.

Another way consumers fought back is the spectacular success of Dr. Sidney Wolfe and his associates at Public Citizen’s Health Research Group. They researched hundreds of prescription drugs and over the counter medicines and found they were not effective for the purpose for which they are advertised. Relentless publicity on such dynamic mass media as the Phil Donahue Show led to the withdrawal of many of these products, likely saving consumers billions of dollars and protecting them from harmful side-effects (see Pills that Don’t Work).

When large companies are fighting regulation their lies become “clear and present dangers” to innocent people. I recall at a technical conference in the early nineteen sixties, a General Motors engineer warned that seatbelts in cars would tear away the inner organs of motorists from their moorings in sudden decelerations as in collisions. For the longest time, lead, asbestos, and a whole host of chemicals were featured as safe, not just necessary. All false.

Someone should write a book about all the prevarications by leading spokespersons of industry and commerce justifying the slavery of the “inferior races,” arguing against the abolition of child labor in dungeon factories, and predicting that legislating social security would bring on communism.

Interestingly, corporations can lie vigorously and not lose credibility. Artificial corporate personhood comes with immunity from social sanctions that apply to real human beings.

In 1972, The People’s Lobby in California, led by the impressive Ed and Joyce Koupal, qualified an initiative called “The Clean Environment Act.” Corporations threw millions of dollars and made false claims to defeat the Act. Their public relations firm, Whitaker and Baxter, put out a fact sheet reaching millions of voters. The oil companies declared that “lowering the lead content of gasoline would cause automobile engines to fail, resulting in massive congestion and transit breakdowns.” They also claimed that “reducing sulfur oxide emissions from diesel fuel would cause the state’s transportation industry to grind to a haul,” with huge joblessness and “economic chaos.”

Other companies said a “moratorium on nuclear power plant construction” would lead to “widespread unemployment and darkened city streets.” Banning DDT in California would “confront the farmer with economic ruin and produce critical shortages of fruits and vegetables” and more lurid hypotheticals.

The lies worked. Voters turned down the initiative by nearly two to one. All these reforms have since been advanced nationwide with no such disasters.