Chris Hedges's Blog, page 151

September 18, 2019

Netanyahu’s Demonization of Palestinian-Israelis Backfires Spectacularly

This piece originally appeared on Informed Comment.

Binyamin Netanyahu appears to have fallen short in his quest for a majority of 61 in the 120-seat Israeli parliament or Knesset. As I write, his far-right Likud Party is tied 32 to 32 with its center-right rival, Blue and White. Netanyahu campaigned frenetically and acted a little unbalanced during this election season, striking militarily as far afield as Iraq and attempting to suppress the internal Palestinian-Israeli vote by proposing putting cameras at voting booths, knowing that discriminated-against Palestinian-Israelis would therefore avoid coming out to vote. The proposal was struck down. But Netanyahu relentlessly demonized the Palestinian-Israelis as wanting to kill all of the Jewish Israelis (this is not true) and warning that his rival, Benny Gantz, would put Palestinian-Israelis, or “Aravim” as Netanyahu calls them with a sneer– horror of horrors– in the Israeli cabinet (this is also not true).

Related Articles

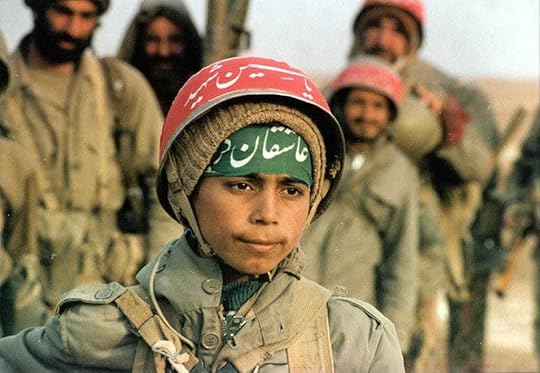

Only a Coalition of the Foolish Wants a War With Iran

by

Netanyahu's Miscalculations About Iran Will Cost Him Dearly

by Juan Cole

The Pro-Israel Extremist Behind Trump's Economic War on Iran

by

Holding a value that 20% of the population must be excluded from high political office is called Jim Crow or Apartheid or just racism. Netanyahu is always going on about how anyone who opposes his colonization of the Palestinian West Bank is a racist bigot, but there really is no greater racist bigot than he. The problem is that his rivals in the Blue and White coalition at least so far agree with him about this exclusion.

And, of course, while Palestinian-Israelis inside Israel can vote in this election, the some 5 million Palestinians living in the Occupied Territories of Gaza and the West Bank are kept stateless and have no vote.

Although Palestinian-Israelis form roughly 20% of the electorate, they have often played a muted role in Israeli politics. In the last Knesset or parliament, they were down to 10 seats out of 120, and turnout among them was only 35%. Palestinian-Israeli members of the Knesset or MK’s have also frequently been ostracized and left voiceless or on occasion even expelled for thought crimes.

Early returns Tuesday evening suggested that the Joint Arab List, a coalition of four parties (Hadash, United Arab List, Balad and Ta’al) will improve to at least 12 seats. Few Arab constituencies had been counted at that time, allegedly in part because of extra scrutiny of those ballots by Israeli authorities.

A large Palestinian-Israeli turnout resulted in large part from the extremist racist language directed at them by Netanyahu.

Channel 12% is claiming to have 85% of results (I don’t know how), producing:

Likud 32

B&W 32

Joint List 12

Shas 9

Beitenu 9

UTJ 8

Yamina 7

Labour-Gesher 6

Democratic Union 5

Right 56

Centre/left/Arabs 55

Liberman 9#Israelex19v2

— Eylon Levy (@EylonALevy) September 18, 2019

The returns are showing fewer seats for the Joint Arab List than did exit polls, which had suggested earlier on Tuesday that there might be as many as 15 seats for them. Since so few Palestinian-Israeli votes have been counted, though, they could still gain another seat or more.

But another possibility is that Benny Gantz, Netanyahu’s rival, might be able to survive at the head of a minority government that is tacitly supported by the Joint Arab List (or by elements of it, since it may splinter). That is, if Gantz can put together a coalition with 55 seats, and the Joint Arab List votes with that coalition informally, then he wouldn’t be in danger of having his government fall.

Gantz’s problem is the same as Netanyahu’s. It would be easy to get to 61 seats if you could entice both the Haridim (ultra-Orthodox religious far right) and the largely ethnically Russian Yisrael Beitenu of Avigdor Lieberman into the same government. But Lieberman and his party are militantly against the influence of the Haredim and have refused to serve with them.

In any case, Lieberman will decide whether Gantz or Netanyahu gets a chance to try to form a government. He has formed a deep dislike of Netanyahu, but for the completely terrifying reason that Netanyahu has not recently made war on little Gaza. Lieberman has suggested a Yisrael Beitenu / Blue and White / Likud government of national unity, but makes it a precondition that Likud dump Netanyahu as party leader.

Although the Joint Arab List got more seats than Lieberman, they will not be able to play kingmakers, since the Jewish parties ostracize them.

It doesn’t matter much who forms the next Israeli government though, for Palestinians. Both major parties have the same creepy kleptomania when it comes to Palestinian land, water and resources.

Our Leaders Are Ensuring Humanity’s Destruction

Worlds end. Every day. We all die sooner or later. When you get to my age, it’s a subject that can’t help but be on your mind.

What’s unusual is this: it’s not just increasingly ancient folks like me who should be thinking such thoughts anymore. After all, worlds of a far larger sort end, too. It’s happened before. Ask the dinosaurs after that asteroid hit the Yucatán. Ask the life forms of the Permian era after what may have been the greatest volcanic uproar the planet ever experienced.

Related Articles

Naomi Klein: We Have Far Less Time Than We Think

by Ilana Novick

Corporate Media Is Misleading Us About Sanders’ Climate Plan

by

Proof Greta Thunberg's Climate Activism Is Working

by

According to a recent U.N. global assessment report, up to one million (that’s 1,000,000!) species are now in danger of extinction, thanks largely to human actions. It’s part of what’s come to be called “the sixth extinction,” a term that makes the point all too clearly. Except in our ability to grasp (or avoid grasping) our seeming determination to wipe away this version of the world, we’re in good company. Five great moments of obliteration preceded us on Planet Earth.

And by the way, that impressive figure for endangered species should probably be upgraded to at least one million and one (1,000,001!). As anthropologist Richard Leakey said years ago, “Homo Sapiens might not only be the agent of the sixth extinction, but also risks being one of its victims.” In other words, it’s evidently not enough for us to turn ourselves into the modern equivalent of the asteroid that took down the dinosaurs, ending the Cretaceous period. It looks as if, in some future that seems ever closer, we might be our own asteroid, the one that will collapse human civilization as we’ve known it.

Planet on Fire

While there are deep mysteries in our present situation, its existence is — or at least should be — anything but a mystery. It’s not even news. After all, in 1965, more than half a century ago, a science advisory committee reported to President Lyndon Johnson with remarkable accuracy on the coming climate crisis. That analysis was based on the previous two centuries in which we humans had been burning fossil fuels in an ever more profligate manner to fashion and develop our way of life on, and command of, this planet. As one of those scientists told Bill Moyers, Johnson’s special assistant coordinating domestic policy, humanity had launched a “‘vast geophysical experiment.’ We were about to burn, within a few generations, the fossil fuels that had slowly accumulated in the earth over the past 500 million years.”

In the process, we would put ever more carbon emissions into the atmosphere and so change the very nature of the planet we were living on. Ignored at the time by a president soon to be swept away by an American war in Vietnam, that report would offer remarkably accurate predictions about how those greenhouse gas emissions would change our twenty-first-century world. A small footnote here: since 1990 — stop a second to take this in — humanity has burned approximately half of all the fossil fuels it’s ever consumed. As my father used to say to me, “Put that in your pipe and smoke it.” And by the way, in the age of Donald Trump, U.S. carbon emissions are once again surging (as they are globally as well).

By now, it should be clear enough that this planet is in crisis. That reality may finally be sinking in somewhat here, as CNN’s recent seven-hour climate-change town hall for Democratic presidential candidates suggested (even after the Democratic National Committee rejected the idea of a televised debate on the subject). And yet this crisis continues to prove a surprisingly hard one for humanity to get its head(s) fully around.

By now, it should be clear enough that this planet is in crisis. That reality may finally be sinking in somewhat here, as CNN’s recent seven-hour climate-change town hall for Democratic presidential candidates suggested (even after the Democratic National Committee rejected the idea of a televised debate on the subject). And yet this crisis continues to prove a surprisingly hard one for humanity to get its head(s) fully around.

And that’s no less true of the mainstream media. A Public Citizen report, for instance, recently offered a snapshot of the then-nonstop coverage of Dorian, the monster Category 5 hurricane that, at one point, had wind gusts up to 220 miles an hour and obliterated parts of the Bahamas before moving on to the U.S. Even though the storm’s intensified behavior fit the expectations of climate scientists to a T, the report found that “climate [change] or global warming was mentioned in just 7.2% of the 167 pieces on ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, MSNBC and Fox.” In the 32 newspapers Public Citizen followed that were covering the storm, “of 363 articles about Dorian…, just nine (2.5%) mentioned climate change.” And I’m sure you won’t be surprised to learn that Fox News went out of its way to denigrate the very idea that there might be a connection between Dorian’s ferocity and the warming of the planet.

One reason awareness of the crisis has sunk in so slowly is obvious enough. Climate change has not been happening in human time; it hasn’t, that is, been taking place in the normal context of history on a timescale that would make it easier for us to grasp how crucial it will prove to be to our everyday lives and those of our children and grandchildren. It’s operating instead on what might be thought of as planetary time. In other words, autocrats or, in the case of our president, potential ones, come and go; their sons take over (or don’t); a revolt topples the autocracy only to turn sour itself; and so it goes in human history. However disturbing such events may be, they are also of our moment and so familiarly graspable.

The climate crisis, however, has been taking place on another timescale entirely and the planet that it’s changing will assumedly feel global warming’s version of autocracy not for a few years, or even a century to come, but potentially for thousands or tens of thousands of years. The results could dwarf what we’ve always known as “history.”

Given the immediacy of our lives and concerns, getting us to focus on predicted events decades or even a century away remains problematic at best. If, as predicted, by 2100 the North China Plain, with its tens of millions of people, becomes partially uninhabitable or Shanghai is drowned thanks to rising sea levels, that’s beyond horrific, but hard to focus on when you’re a government or a people plunged into an immediate trade war with the globe’s other great power; hard to react to when the needs of today and tomorrow, this year and next, seem so pressing, and when you’re still exporting hundreds of coal-fired power plants to other parts of the world.

It shouldn’t be surprising that it’s been so difficult for most of us to respond to the climate crisis over these last decades when its effects, while noticeable enough if you’re looking for them, hadn’t yet impinged in obvious ways on most of our lives. It seemed to matter little that what was being prepared for delivery might be the collective asteroid of human history.

Consider this the ultimate sign of how difficult it’s been to take in a crisis that, in its magnitude and span, seems to mock the human version of time: in these years, vast numbers of people haven’t hesitated to elect (or support) a crew of pyromaniacs as their leaders. From the U.S. to Brazil, Poland to Australia, Russia to Saudi Arabia, coming to power in these years across significant parts of the planet are men — and they are men — who seem intent on ignoring or rejecting the very idea that we are altering the planet’s climate at a rapid rate. They have, in fact, generally been strikingly transparent in their blunt urge not just to overlook the climate crisis, but to actually increase its intensity through the greater use of fossil fuels, while often trying to deep-six or ignore alternative forms of energy.

In other words, blind to our future fate and that of our children and grandchildren, humanity has been installing in power leaders who are the literal raw material for ensuring that the collective asteroid of human history will indeed be delivered. In an ongoing gesture of self-destruction, humanity has been tapping what might be thought of as Pyromaniacs, Incorporated, to run the world.

The Greatest Crime of All

All that may be changing, however, for an obvious reason — even if the first sign of that change couldn’t have been more modest or less Trumpian: a 15-year-old Swedish girl who, in 2018, began skipping school, Friday after Friday, to perch on the steps of the Swedish parliament building, holding a handmade banner (“school strike for climate”). Not even her parents initially encouraged her “Fridays for Future” protest against what this planet’s adults were visibly doing: stealing her generation’s future. In the end, Greta Thunberg would unexpectedly spark a movement of the young, increasingly aware that their future was in peril, that, in various forms, spread (and is still spreading) across the planet. It may prove to be the most hopeful movement of our times.

As it happened, Thunberg began that strike of hers at a crucial juncture, just at the edge of the moment when climate change would start to enter human time as a crisis in everyday life. In retrospect, we may come to see the summer of 2019 as a turning point in the reaction to that phenomenon. This summer, almost anywhere you lived, climate change seemed to be in view. The Brazilian Amazon was burning (as were similar rain forests in Africa and Indonesia); Alaska, too, was burning, its sea ice gone for the first time in history, its fire season extended by two months. Burning as well in record fashion were areas across much of the rest of the Far North, especially Siberia, where forests and peatlands sent vast plumes of smoke into space (while releasing startling amounts of carbon into the atmosphere); flooding hit the American Midwest in an unparalleled fashion, while record summer heat, drought, and an early fire season clobbered Australia; water scarcity struck areas of the planet in new ways, including Chennai, an Indian city of nine million that practically lost its water supply to drought; and Europe experienced three unprecedented heat waves, with temperatures soaring across the continent. Much of this seemed to be happening at a pace that exceeded the predictions of climate scientists. The government of Iceland held a “funeral” for the first glacier lost to global warming, while Greenland’s ice sheet experienced what may prove to be a record melt and sea ice continued to disappear at a startling clip in both the Arctic and Antarctic. The Arctic was already heating at double the rate of the rest of the planet, as was Canada. And don’t forget that, as the globe’s oceans continued to warm in a striking fashion, storms like Dorian were intensifying (and the numbers of weather-displaced people hitting record levels globally).

And so it went. We humans were no longer simply living with predictions about what might happen in 2030, 2050, 2100, or thereafter, about possibilities that, while grim, seemed far away when the endless crises of everyday life beckoned. We were suddenly in an increasingly overheated present, one visibly changing, visibly intensifying in ways we hadn’t previously experienced.

In the summer of 2019, from the tropics to the poles, we found ourselves, in short, on an already burning, melting planet and it showed, even in opinion polls in this country. An acceptance that climate change was actually happening and mattered was clearly growing. It would prove increasingly visible in the Democratic rollout for the 2020 election and even, as the New York Times reported, in the secret worries of Republican strategists that younger conservative voters, “who in their lifetimes haven’t seen a single month of colder-than-average temperatures globally, and who call climate change a top priority,” might in the future be alienated from the party.

In a remarkable recent article, Stephen Pyne, historian of fire, offered a vision of what’s happening as humans, a “keystone species for fire,” essentially toast the planet. Historically speaking, as he points out, the crucial development was that, with the industrial revolution, humans turned

“from burning living landscapes to burning lithic ones in the form of fossil fuels. That is the Big Burn of today, acting as a performance enhancer on all aspects of fire’s global presence. So vast is the magnitude of these changes that we might rightly speak of a coming Fire Age equivalent in stature to the Ice Ages of the Pleistocene. Call it the Pyrocene.”

And if, from Paradise, California, to Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas, we have indeed already entered the Pyrocene Age, expect the pyres only to grow. After all, the government of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is almost literally setting fire to the Amazon rain forest (a job that human arsonists may have started, but that those forests could self-destructively end all on their own). Similarly, in the U.S., the Trump administration has been reversing climate-change-related rules or regulations of every sort, trying to open ever more American landscapes to oil and natural gas drilling, and working to ensure that yet more methane, a particularly powerful greenhouse gas, will be released into the atmosphere. And that’s just to begin a list of such horrors.

Keep in mind as well that the brutal summer of 2019 is guaranteed to prove anything but “the new normal.” In fact, there can be no new normal as long as those greenhouse gases continue to pour into the atmosphere. Admittedly, we humans are a notoriously clever species. Who could doubt that, if we ever truly mobilized, launching the equivalent of World War II’s Manhattan Project that produced the first atomic bomb — the other way we’ve found to asteroid ourselves to death — something might indeed happen? Various methods might be found to deal with or sequester carbon emissions, while far more effort might be put into developing non-carbon-emitting forms of energy.

In the meantime, from Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro to the CEOs of all those fossil-fuel companies, we’re still left with the pyromaniacs largely in charge. If they have their way, they will undoubtedly take their pleasures and profits and not give a damn about turning much of this world into an oven for the Greta Thunbergs of the future.

Think of this as a planet on the precipice. If Pyromaniacs, Inc., succeeds, if the arsonists are truly able to persevere, there will have been no crime like this in history, none at all.

September 17, 2019

Trump Strains to Balance Diplomacy, Military Threat to Iran

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration tried to balance diplomacy with fresh talk of military action Tuesday in response to the fiery missile and drone attack on the heart of Saudi Arabia’s oil industry — a strike marking the most explosive consequence yet of the “maximum pressure” U.S. economic campaign against Iran.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was headed to Jiddah in Saudi Arabia to discuss possible responses to what U.S. officials believe was an attack coming from Iranian soil. President Donald Trump said he’d “prefer not” to meet with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at next week’s U.N. session but “I never rule anything out.”

Iran continued to deny involvement in last weekend’s attack on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq oil processing plant and its Khurais oil field, a strike that interrupted the equivalent of about 5% of the world’s daily supply. Saudi Arabia’s energy minister said Tuesday that more than half of the country’s daily crude oil production that was knocked out by the attack had been recovered and production capacity at the targeted plants would be fully restored by the end of the month.

Related Articles

Only a Coalition of the Foolish Wants a War With Iran

by

Will John Bolton's Firing Save Us From War With Iran?

by Juan Cole

How the U.S. and Iran Got to This Tense Moment

by Medea Benjamin

The Trump administration was moving cautiously as it navigated competing impulses — seeking to keep up a pressure campaign aimed at forcing Tehran to negotiate on broader issues with the U.S. while deterring any further Iranian attacks and avoiding another Middle East war. It all was occurring as the administration deals with a host of other foreign policy issues and has no national security adviser, following the recent ouster of John Bolton.

Echoing Trump’s warning from earlier in the week, Vice President Mike Pence said American forces were “locked and loaded” for war if needed. But he also noted that Trump said he doesn’t want war with Iran or anyone else.

“As the president said yesterday, it’s ‘certainly looking like’ Iran was behind these attacks,” Pence said. “And our intelligence community at this very hour is working diligently to review the evidence.”

The analysts’ task was to connect the dots provided by satellite data and other highly classified intelligence with physical evidence from the scene of the attack, which American-provided Saudi defenses had failed to stop.

Fourteen months before voters will decide on Trump’s reelection, he is increasingly mindful of his 2016 campaign promises, including his pledge to bring American troops home after nearly two decades of continuous war.

But he also promised to apply fresh pressure on Iran, a pledge complicated by the latest apparent provocation. The at-times divergent messages from his administration, officials say, mirror internal staff divisions and even the president’s own hesitations.

“You know, I’m not looking to get into new conflict,” Trump said Monday, “but sometimes you have to.”

Aides say he’s taking a prudent pause.

“The president’s being cautious, and if he were banging the gong today about Iran being the culprit, inevitably, without presenting the case to the American people, everyone would be saying he’s a warmonger,” said White House spokesman Hogan Gidley.

The crisis comes amid upheaval in Trump’s national security team. His national security adviser, Bolton, departed earlier this month after policy clashes, including disagreements over how best to pressure Iran into returning to the negotiating table on its nuclear and missile programs.

Iran’s alleged involvement in a recent series of provocations in the Gulf coincides with key moments in the unraveling of the country’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, from which Trump unilaterally withdrew the U.S. in May of last year. That was followed by a U.S. economic sanctions campaign, dubbed “maximum pressure,” that has cut off much of Iran’s international oil exports.

Iran, in turn, has said that no one will be able to export oil from the region if Tehran can’t In effect, the country has answered Trump’s economic warfare with its own version — attacks on economic targets that have been audacious but thus far not caused casualties.

Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said Tuesday that U.S. military experts were in Saudi Arabia working with counterparts to “do the forensics on the attack” — gleaning evidence that could help build a convincing case for where the weapons originated.

Speaking to reporters in London, Dunford noted — as Trump had on Monday — that the attack was not aimed at the United States or U.S. forces. Therefore, he said, no steps were being taken to beef up the U.S. military presence in the Gulf region, which includes air defense forces and support troops at Prince Sultan Air Base south of the Saudi capital of Riyadh. The U.S. Navy has an aircraft carrier battle group in the area and fighter and bomber aircraft elsewhere in the Gulf.

Jon Alterman, director of the Middle East program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said Trump must fashion a response to Iran that fits his administration’s stated priority of shifting from decades of insurgency warfare in Afghanistan and the Middle East to better position the U.S. for more serious international conflict.

“The military’s instinct is increasingly that you can continue to pour resources into confronting Iran, but you’re never going to fix the problem and, most importantly, you’re taking resources away from confronting the real threats to the United States, which are China and Russia,” he said.

Trump also faces a skeptical Congress. A bipartisan group of House members on Monday called for new language in 2020 defense spending bills that would prevent the president from starting a war with Iran without congressional authorization.

Pence met behind closed doors on Capitol Hill with Senate Republicans, and lawmakers were reviewing classified intelligence about the attack. Some Republican senators said a three-page document shared with Congress is convincing that Iran was behind the attack.

Sen. Ron Johnson, a Wisconsin Republican, said he was “100 percent convinced” it was Iran.

Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, a Trump ally, said the president is trying to build a regional coalition before any action.

“I think the appropriate response would be to knock one of the refineries in Iran out of business,” Graham told reporters. He has spoken to the president and expects more information at an “appropriate time.”

Democratic Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia, a member of the Armed Services Committee, acknowledged the intelligence is “pretty good” that there’s an Iran connection, but he warned the Trump administration off a military response.

“The administration is lying to the American people when they say it was an unprovoked attack,” Kaine said, arguing the U.S. imposed sanctions and other withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal are provoking Iran’s behavior.

“We should not go to war to protect Saudi oil, but we should not go to another war that’s premised upon lying to the American public,” Kaine said.

___

AP Writers Aya Batrawy and Jon Gambrell contributed from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Also contributing were Lolita C. Baldor in London and Lisa Mascaro, Zeke Miller, Sagar Meghani and Michael Biesecker in Washington.

Naomi Klein: We Have Far Less Time Than We Think

Canadian author, social activist and filmmaker Naomi Klein is done with “tinkering and denial” as solutions to climate change. As she explains in her new book, “On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal,” America, and the world, is way past the point where a single policy, or even market-based solutions, can cut carbon emissions, increase production of renewable energy, repair broken ecosystems and generally prevent the kinds of climate catastrophe that will hurt the earth and the humans on it.

“We’re all alive at the last possible moment,” Klein writes, “when changing course can mean saving lives on a truly unimaginable scale.”

Related Articles

This Radical Plan to Fund the ‘Green New Deal’ Just Might Work

by Ellen Brown

Mike Pompeo Is Inviting Catastrophe in the Arctic

by

The Big American Bribery Scandal Isn’t Felicity Huffman’s $15,000

by

That means we need a worldwide Green New Deal: policy proposals and programs for avoiding climate catastrophe.

According to Klein, it’s young people, that is, students, not political and business leaders, who see the ability to save lives as an imperative, one that goes beyond individual choice. On Friday, students across the world will leave class to participate in climate strikes, demanding that the adults in power finally take action to combat the impacts of a warming planet.

In fact, the climate movement started by activist Greta Thunberg, a Swedish high school student who kicked off a wave of school strikes in 2018, is the subject of the introduction to Klein’s book. It’s Klein’s opening salvo in a collection of longform essays touching on the need for a Green New Deal, the science behind it and the obstacles to achieving it. Klein also addresses, why, in contrast to previous policies, this needs to be an intersectional movement, one that seeks to address the environmental damage caused by imperialism and racism, by colonial powers who took resources from indigenous communities, hurting the earth along with their livelihoods. Where the original New Deal’s benefits extended mainly to white Americans, Klein is adamant that the Green version be beneficial to all. Teens like Thunberg, Klein believes, understand much better than adults what is at stake.

Some U.S. leaders are also acting on environmental activists’ concerns. In February, Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Ed. Markey, D-Mass., unveiled their version of the Green New Deal, which includes numerous emissions cuts, investments in renewable energy and job retraining programs.

As Lisa Friedman wrote in The New York Times at the time, Markey and Ocasio-Cortez were not the first to propose this idea, variations of which have been around for years. Political momentum for the idea, however, became stronger after the 2018 midterms, when, as Friedman says, “a youth activist group called the Sunrise Movement popularized the name.” They laid out a strategy and held a sit-in outside Nancy Pelosi’s office to demand action. Ocasio-Cortez joined them, “lending her support to their proposal and setting the groundwork for what ultimately became the joint resolution.”

Today, Democratic presidential candidates have begun to back the resolution, further building momentum. Klein is hopeful, but thinks America has a lot to learn, both from its own previous mistakes, as well as those of other countries.

On the eve of her new book’s release, Klein spoke with Truthdig’s Ilana Novick by phone about why she wrote the book, public opinion on climate change, why a Green New Deal is good for the economy and why big structural changes to our economy, our consumption, and our culture, are the answer.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Ilana Novick: Why did you want to write this book now?

Naomi Klein: We have a very, very thin path right now, very narrow path to win a really transformational climate plan that’s going under the name the Green New Deal. A lot of things need to align if that is going to become a political possibility. And the next year is incredibly important in the United States. And specifically, in terms of helping elect a candidate that backs a really bold a Green New Deal vision, winning the White House, getting started on day one.

So the book is my best effort at marshaling what I consider to be the critical arguments for why this really is the only pathway to lowering emissions in line with science. And arguing that that project must be linked in every way with a plan to reduce every form of inequality: economic, racial, gender and more. That’s why I put it out now.

IN: I wanted to ask about what might be included in a Green New Deal. You write that rather than “tinkering” with individual policies or programs like a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system, we need wholesale structural change. Why is tinkering with the problem not enough right now?

NK: the important thing to understand is that this discussion is not starting in 2019. The world has been talking about lowering emissions for 30 years. And in that time, many large economies have in fact introduced carbon taxes, cap-and-trade schemes, various market-based approaches to tackle the climate crisis. In the Kyoto Protocol, that pathway, as opposed to a more regulatory approach, is in the text of the agreement, right.

So you have … the European Union has a carbon market, California has a carbon market, British Columbia has a carbon tax. So we’re not having a theoretical debate about which way might work better. We actually have decades of field data about whether this type of an approach lowers emissions in line with what scientists are telling us we need to do, right.

What we know is that you can win some marginal carbon reductions using these types of mechanisms, but you don’t get anywhere near what climate scientists are telling us we need to do if we’re going to keep temperatures below two degrees Celsius, let alone 1.5 [degrees], which they’re telling us should be our target. This is what the IPCC made clear in its landmark report last October, which said that we had just 11 years to cut global emissions in half if we’re going to prevent really catastrophic levels of warming at two degrees. So we know that a carbon tax can’t do it.

IN: Why do these ideas fail to make an impact?

NK: If you look at, for instance, British Columbia, which is often held up as one of the better carbon tax schemes, it hasn’t delivered. Emissions have actually gone up almost every year in British Columbia under the carbon tax. It probably would have gone up more without it. But the point is it’s nowhere close to the kind of sharp emission reductions we need.

The other thing we see with carbon pricing schemes is that they often get undone because of a backlash, because they’re seen as unjust, and often rightly so, right. So in France when Emmanuel Macron introduced a carbon pricing scheme that increased the cost of petroleum for working people at the same time as he had handed out tax cuts to the very rich in France, it led to this massive backlash known as the Yellow Vest movement. … And ultimately, he rolled it back.

IN: What do we need instead?

NK: So, when we’re thinking about what policies work, we have to be asking, first of all, what policies will lower emissions in line with science. But also, what policies are going to get enough popular buy-in that they won’t spark a popular backlash and just be undone. And that’s the key, I think, of a Green New Deal approach, which links the need to lower emissions in line with science with the need to create huge numbers of good union jobs with very strong protections for workers, as well as linking it with services, like health care, Medicare for all, free public education, that are tremendously popular and are going to make life better and easier for huge numbers of people.

IN: You write about a tension between large-scale laws and regulations that would curb emissions and that would try to limit our dependence on oil and natural gas and toward things like renewable energy, and the fact that these regulations will mean job losses. So, it’s sort of pitting the environment against the economy. Why is that potentially incorrect, or if approaches to preventing climate catastrophe can be implemented without economic backlash or not impact jobs?

NK: Right. What the IPCC said last October is that in order to keep temperatures at anything like … I hesitate to use the word safe, because that’s not what they’re saying. Because we’ve gone beyond safe already. I mean, if you look at the climate impacts that we’re seeing with just one degree of warming, [with Hurricanes] in Puerto Rico, in [the Bahamas], in Houston, [and] with record-breaking fires, I mean, we’re already beyond safe levels, right.

But what the IPCC has said is that the best we can hope for at this point is keeping temperatures below 1.5 degrees Celsius. And they said that that would require unprecedented transformations of every aspect of society. So that means housing, transportation, energy, agriculture, and they spelled this out, right. So, if you’re going to transform every aspect of your society, you’re going to create a lot of jobs. And that’s what a Green New Deal is about.

But I think where the jobs versus environment argument gets traction is that I think the environmental movement has historically not paid nearly enough attention to the fact that these green jobs need to be good jobs. They need to be as good as the unionized jobs in the fossil fuel sector that workers would be transitioning from. So I think that it’s absolutely critical that unions are—and other worker organizations, because unions only represent a fraction of workers in this country—are at the table planning what a Green New Deal would look like, what the retraining programs would look like, what the job conditions in this post-carbon economy would look like.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of mistrust that is well earned, because I think for a long time these jobs in different sectors were really treated as interchangeable. And in fact, a lot of renewable energy jobs are nonunion jobs that pay significantly lower salaries than the jobs in higher carbon sectors where unions have worked over many decades to win some of the best working conditions in the blue-collar workforce.

IN: How do you make sure that workers, and particularly workers of color and women, and other marginalized groups have a seat at the table?

NK: Right. I think it means that the green movement has to be taking on the supposedly green companies that are engaged in union busting, like Tesla, and fighting alongside unions to make sure that green jobs are good, unionized jobs.

It’s also in the text of the AOC, of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey’s resolution that there should be not only a jobs guarantee, but that workers should be guaranteed to be paid at the same level, same level of salary and benefits in their new jobs as they were in their older jobs. So that’s in the text of the resolution. These are protections that can and must be built into the transition.

That said, we have to be clear-eyed that no matter what those fighting for a Green New Deal do, there will be a barrage of lies put out by the fossil fuel sector about how this is just going to kill jobs and not replace them with anything, because this is what they do. They have limitless amounts of money to lie. Unfortunately, there are some trade union leaders that have aligned their interests with the owners of these companies, in many cases more than the interests of their own workers and their families. And there needs to be accountability there too.

IN: I also wanted to ask about changes in public opinion when it comes to climate action. I kind of remember, it was vaguely foreseen in elementary school in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and hearing about reduce, reuse, recycle. And then I remember in 2008 at the very beginning of the Obama administration there was more urgency around the issue. And you point to public opinion polls in 2008 suggesting Americans were very concerned about climate change, and then two or three years later, they weren’t. What happened?

NK: Right. When you look at polling around the momentum for climate action, it actually hews very closely to how well the economy is doing. So because the kinds of climate policies that have tended to be on the agenda have been these market-based solutions, like a carbon tax for instance, right, or cap and trade or maybe paying a little bit more for renewable energy, right, what often happens is that people will get scared about the science. A film like “An Inconvenient Truth” will come out. There’ll be a sense of “Yes, we have to do this.” And then there’ll be a recession, right. People will be struggling to hold on to their homes, they will be desperately looking for jobs and facing those daily crises in an economic emergency.

And then what happens is that interest in climate action goes down, because as they say in France, the gilet jaunes [yellow vest] movement, “You care about the end of the world. We care about the end of the month,” right. And so that’s what happened during the Obama years. There was this momentum, but as the recession really began to bite, the momentum, climate action came to be equated with a luxury that you couldn’t afford in a time of economic downturn.

IN: What makes a Green New Deal different?

NK: One of the most overlooked benefits of a Green New Deal-style approach, is that this is an approach to lowering emissions that is modeled off of the most famous economic stimulus of all time, which is the New Deal, right, which was developed as a response to the greatest economic crisis the world has ever faced, which was the Great Depression.

So what that means is that right now there is a lot of … people are telling pollsters that they care about climate change. But we also know that we may face a recession in the next year or two. And if we take the same sorts of approach of carbon tax, cap and trade, we should fully expect whatever momentum has been built now to dissipate if there is an economic crisis. However, if we embrace a Green New Deal approach, which is all about creating jobs, transforming infrastructure, that actually support for it will grow if there is a recession, because the need for those jobs and the need for that kind of economic stimulus will only increase.

IN: Given the political landscape that we’re in and that we don’t have that much time, why is it so important do you think to fight for these larger changes, even given that we don’t have that much time and also that we might need a lot of time?

NK: Look, we have a deadline; we have to pass global emissions in 11 years, right. And when a new administration would be taking office, if all goes well, that would be 10 years. There is no way to achieve that level of emission reduction cuts without a transformation of infrastructure. It’s just not possible. That’s what the IPCC has said. You are talking about changing where we get our energy, how we get our energy, how we move ourselves around, how we grow our food. That’s the only way you get those emission reductions. So it’s not like … nobody’s ever saying this is easy. Nobody is saying that there aren’t massive obstacles. But on the other side, nobody is actually presenting an alternate plan that is in line with science.

IN: One passage in the book that particularly struck me was when you talked to a woman protesting, saying, “The hard truth is that the answer to the question ‘What can I, as an individual, do to stop climate change?’ is: nothing.” I wondered if you could talk a little bit more about that, because I think there is a growing tension between individual actions, like cutting out meat and driving less and trying to lobbying for giant corporations and governments to reduce their carbon emissions, even change their whole business models, to protect the environment.

NK: Well, I think that I don’t think anybody is arguing or I mean anybody serious is arguing that we are going to achieve the levels of emission reductions that we need through voluntary lifestyle changes. There’s no doubt that you can lower your own personal carbon footprint, right, by cutting out meat, by not flying, by not driving or driving electric [cars] powered by renewables. Most people don’t have these choices, and in order for this to add up to the level of change that we need, you would need every single person to voluntarily do it.

But that said, if we look at the historical precedence where we have seen massive societal change, whether it is the New Deal or whether it is the transformations of the American economy during the Second World War, it was absolutely critical that there was a perception of fairness. Meaning that it was not only working people who were being asked to make changes, to make sacrifices, that it was also massive corporations who were being dragged kicking and screaming to also make sacrifices, to also make changes, to also abide by new regulations that impacted their profits.

And that perception of fairness was absolutely critical in terms of people accepting the change. What we see in France with the gilet jaunes movement is that it is precisely the double standard, right, of seeing the tax breaks being given to big polluters and multimillionaires whose carbon footprints are sky high, while people who are already facing all of these stresses in a precarious economy are being asked to pay more.

I don’t think anybody serious seriously is saying voluntary lifestyle changes are going to do it. But I do think that you can make a serious argument that it’s important if you can, to change your lifestyle so that you can see and show others that actually it is possible to live well within our carbon budget. And that is an important kind of lived reality to be able to hold up in the face of all of this scaremongering that you’re going to get from the Fox Newses and all of the fossil fuel talking points that this is about just destroying people’s lives and so on, right. There are going to be sacrifices if we design this well.

We’re also going to have way better public transit. We can have better jobs and better working conditions, better services like for health care and education and a care economy. We can have a renaissance in public art. There are things that will improve. And yes, there are some things that will contract. We have to be honest about that.

Naomi Klein: The Green New Deal is the Last Best Hope to Save the Planet

Canadian author, social activist and filmmaker Naomi Klein is done with “tinkering and denial” as solutions to climate change. As she explains in her new book, “On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal,” America, and the world, is way past the point where a single policy, or even market-based solutions, can cut carbon emissions, increase production of renewable energy, repair broken ecosystems and generally prevent the kinds of climate catastrophe that will hurt the earth and the humans on it.

“We’re all alive at the last possible moment,” Klein writes, “when changing course can mean saving lives on a truly unimaginable scale.”

That means we need a worldwide Green New Deal: policy proposals and programs for avoiding climate catastrophe.

According to Klein, it’s young people, that is, students, not political and business leaders, who see the ability to save lives as an imperative, one that goes beyond individual choice. On Friday, students across the world will leave class to participate in climate strikes, demanding that the adults in power finally take action to combat the impacts of a warming planet.

In fact, the climate movement started by activist Greta Thunberg, a Swedish high school student who kicked off a wave of school strikes in 2018, is the subject of the introduction to Klein’s book. It’s Klein’s opening salvo in a collection of longform essays touching on the need for a Green New Deal, the science behind it and the obstacles to achieving it. Klein also addresses, why, in contrast to previous policies, this needs to be an intersectional movement, one that seeks to address the environmental damage caused by imperialism and racism, by colonial powers who took resources from indigenous communities, hurting the earth along with their livelihoods. Where the original New Deal’s benefits extended mainly to white Americans, Klein is adamant that the Green version be beneficial to all. Teens like Thunberg, Klein believes, understand much better than adults what is at stake.

Some U.S. leaders are also acting on environmental activists’ concerns. In February, Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Ed. Markey, D-Mass., unveiled their version of the Green New Deal, which includes numerous emissions cuts, investments in renewable energy and job retraining programs.

As Lisa Friedman wrote in The New York Times at the time, Markey and Ocasio-Cortez were not the first to propose this idea, variations of which have been around for years. Political momentum for the idea, however, became stronger after the 2018 midterms, when, as Friedman says, “a youth activist group called the Sunrise Movement popularized the name.” They laid out a strategy and held a sit-in outside Nancy Pelosi’s office to demand action. Ocasio-Cortez joined them, “lending her support to their proposal and setting the groundwork for what ultimately became the joint resolution.”

Today, Democratic presidential candidates have begun to back the resolution, further building momentum. Klein is hopeful, but thinks America has a lot to learn, both from its own previous mistakes, as well as those of other countries.

On the eve of her new book’s release, Klein spoke with Truthdig’s Ilana Novick by phone about why she wrote the book, public opinion on climate change, why a Green New Deal is good for the economy and why big structural changes to our economy, our consumption, and our culture, are the answer.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Ilana Novick: Why did you want to write this book now?

Naomi Klein: We have a very, very thin path right now, very narrow path to win a really transformational climate plan that’s going under the name the Green New Deal. A lot of things need to align if that is going to become a political possibility. And the next year is incredibly important in the United States. And specifically, in terms of helping elect a candidate that backs a really bold a Green New Deal vision, winning the White House, getting started on day one.

So the book is my best effort at marshaling what I consider to be the critical arguments for why this really is the only pathway to lowering emissions in line with science. And arguing that that project must be linked in every way with a plan to reduce every form of inequality: economic, racial, gender and more. That’s why I put it out now.

IN: I wanted to ask about what might be included in a Green New Deal. You write that rather than “tinkering” with individual policies or programs like a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system, we need wholesale structural change. Why is tinkering with the problem not enough right now?

NK: the important thing to understand is that this discussion is not starting in 2019. The world has been talking about lowering emissions for 30 years. And in that time, many large economies have in fact introduced carbon taxes, cap-and-trade schemes, various market-based approaches to tackle the climate crisis. In the Kyoto Protocol, that pathway, as opposed to a more regulatory approach, is in the text of the agreement, right.

So you have … the European Union has a carbon market, California has a carbon market, British Columbia has a carbon tax. So we’re not having a theoretical debate about which way might work better. We actually have decades of field data about whether this type of an approach lowers emissions in line with what scientists are telling us we need to do, right.

What we know is that you can win some marginal carbon reductions using these types of mechanisms, but you don’t get anywhere near what climate scientists are telling us we need to do if we’re going to keep temperatures below two degrees Celsius, let alone 1.5 [degrees], which they’re telling us should be our target. This is what the IPCC made clear in its landmark report last October, which said that we had just 11 years to cut global emissions in half if we’re going to prevent really catastrophic levels of warming at two degrees. So we know that a carbon tax can’t do it.

IN: Why do these ideas fail to make an impact?

NK: If you look at, for instance, British Columbia, which is often held up as one of the better carbon tax schemes, it hasn’t delivered. Emissions have actually gone up almost every year in British Columbia under the carbon tax. It probably would have gone up more without it. But the point is it’s nowhere close to the kind of sharp emission reductions we need.

The other thing we see with carbon pricing schemes is that they often get undone because of a backlash, because they’re seen as unjust, and often rightly so, right. So in France when Emmanuel Macron introduced a carbon pricing scheme that increased the cost of petroleum for working people at the same time as he had handed out tax cuts to the very rich in France, it led to this massive backlash known as the Yellow Vest movement. … And ultimately, he rolled it back.

IN: What do we need instead?

NK: So, when we’re thinking about what policies work, we have to be asking, first of all, what policies will lower emissions in line with science. But also, what policies are going to get enough popular buy-in that they won’t spark a popular backlash and just be undone. And that’s the key, I think, of a Green New Deal approach, which links the need to lower emissions in line with science with the need to create huge numbers of good union jobs with very strong protections for workers, as well as linking it with services, like health care, Medicare for all, free public education, that are tremendously popular and are going to make life better and easier for huge numbers of people.

IN: You write about a tension between large-scale laws and regulations that would curb emissions and that would try to limit our dependence on oil and natural gas and toward things like renewable energy, and the fact that these regulations will mean job losses. So, it’s sort of pitting the environment against the economy. Why is that potentially incorrect, or if approaches to preventing climate catastrophe can be implemented without economic backlash or not impact jobs?

NK: Right. What the IPCC said last October is that in order to keep temperatures at anything like … I hesitate to use the word safe, because that’s not what they’re saying. Because we’ve gone beyond safe already. I mean, if you look at the climate impacts that we’re seeing with just one degree of warming, [with Hurricanes] in Puerto Rico, in [the Bahamas], in Houston, [and] with record-breaking fires, I mean, we’re already beyond safe levels, right.

But what the IPCC has said is that the best we can hope for at this point is keeping temperatures below 1.5 degrees Celsius. And they said that that would require unprecedented transformations of every aspect of society. So that means housing, transportation, energy, agriculture, and they spelled this out, right. So, if you’re going to transform every aspect of your society, you’re going to create a lot of jobs. And that’s what a Green New Deal is about.

But I think where the jobs versus environment argument gets traction is that I think the environmental movement has historically not paid nearly enough attention to the fact that these green jobs need to be good jobs. They need to be as good as the unionized jobs in the fossil fuel sector that workers would be transitioning from. So I think that it’s absolutely critical that unions are—and other worker organizations, because unions only represent a fraction of workers in this country—are at the table planning what a Green New Deal would look like, what the retraining programs would look like, what the job conditions in this post-carbon economy would look like.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of mistrust that is well earned, because I think for a long time these jobs in different sectors were really treated as interchangeable. And in fact, a lot of renewable energy jobs are nonunion jobs that pay significantly lower salaries than the jobs in higher carbon sectors where unions have worked over many decades to win some of the best working conditions in the blue-collar workforce.

IN: How do you make sure that workers, and particularly workers of color and women, and other marginalized groups have a seat at the table?

NK: Right. I think it means that the green movement has to be taking on the supposedly green companies that are engaged in union busting, like Tesla, and fighting alongside unions to make sure that green jobs are good, unionized jobs.

It’s also in the text of the AOC, of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey’s resolution that there should be not only a jobs guarantee, but that workers should be guaranteed to be paid at the same level, same level of salary and benefits in their new jobs as they were in their older jobs. So that’s in the text of the resolution. These are protections that can and must be built into the transition.

That said, we have to be clear-eyed that no matter what those fighting for a Green New Deal do, there will be a barrage of lies put out by the fossil fuel sector about how this is just going to kill jobs and not replace them with anything, because this is what they do. They have limitless amounts of money to lie. Unfortunately, there are some trade union leaders that have aligned their interests with the owners of these companies, in many cases more than the interests of their own workers and their families. And there needs to be accountability there too.

IN: I also wanted to ask about changes in public opinion when it comes to climate action. I kind of remember, it was vaguely foreseen in elementary school in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and hearing about reduce, reuse, recycle. And then I remember in 2008 at the very beginning of the Obama administration there was more urgency around the issue. And you point to public opinion polls in 2008 suggesting Americans were very concerned about climate change, and then two or three years later, they weren’t. What happened?

NK: Right. When you look at polling around the momentum for climate action, it actually hews very closely to how well the economy is doing. So because the kinds of climate policies that have tended to be on the agenda have been these market-based solutions, like a carbon tax for instance, right, or cap and trade or maybe paying a little bit more for renewable energy, right, what often happens is that people will get scared about the science. A film like “An Inconvenient Truth” will come out. There’ll be a sense of “Yes, we have to do this.” And then there’ll be a recession, right. People will be struggling to hold on to their homes, they will be desperately looking for jobs and facing those daily crises in an economic emergency.

And then what happens is that interest in climate action goes down, because as they say in France, the gilet jaunes [yellow vest] movement, “You care about the end of the world. We care about the end of the month,” right. And so that’s what happened during the Obama years. There was this momentum, but as the recession really began to bite, the momentum, climate action came to be equated with a luxury that you couldn’t afford in a time of economic downturn.

IN: What makes a Green New Deal different?

NK: One of the most overlooked benefits of a Green New Deal-style approach, is that this is an approach to lowering emissions that is modeled off of the most famous economic stimulus of all time, which is the New Deal, right, which was developed as a response to the greatest economic crisis the world has ever faced, which was the Great Depression.

So what that means is that right now there is a lot of … people are telling pollsters that they care about climate change. But we also know that we may face a recession in the next year or two. And if we take the same sorts of approach of carbon tax, cap and trade, we should fully expect whatever momentum has been built now to dissipate if there is an economic crisis. However, if we embrace a Green New Deal approach, which is all about creating jobs, transforming infrastructure, that actually support for it will grow if there is a recession, because the need for those jobs and the need for that kind of economic stimulus will only increase.

IN: Given the political landscape that we’re in and that we don’t have that much time, why is it so important do you think to fight for these larger changes, even given that we don’t have that much time and also that we might need a lot of time?

NK: Look, we have a deadline; we have to pass global emissions in 11 years, right. And when a new administration would be taking office, if all goes well, that would be 10 years. There is no way to achieve that level of emission reduction cuts without a transformation of infrastructure. It’s just not possible. That’s what the IPCC has said. You are talking about changing where we get our energy, how we get our energy, how we move ourselves around, how we grow our food. That’s the only way you get those emission reductions. So it’s not like … nobody’s ever saying this is easy. Nobody is saying that there aren’t massive obstacles. But on the other side, nobody is actually presenting an alternate plan that is in line with science.

IN: One passage in the book that particularly struck me was when you talked to a woman protesting, saying, “The hard truth is that the answer to the question ‘What can I, as an individual, do to stop climate change?’ is: nothing.” I wondered if you could talk a little bit more about that, because I think there is a growing tension between individual actions, like cutting out meat and driving less and trying to lobbying for giant corporations and governments to reduce their carbon emissions, even change their whole business models, to protect the environment.

NK: Well, I think that I don’t think anybody is arguing or I mean anybody serious is arguing that we are going to achieve the levels of emission reductions that we need through voluntary lifestyle changes. There’s no doubt that you can lower your own personal carbon footprint, right, by cutting out meat, by not flying, by not driving or driving electric [cars] powered by renewables. Most people don’t have these choices, and in order for this to add up to the level of change that we need, you would need every single person to voluntarily do it.

But that said, if we look at the historical precedence where we have seen massive societal change, whether it is the New Deal or whether it is the transformations of the American economy during the Second World War, it was absolutely critical that there was a perception of fairness. Meaning that it was not only working people who were being asked to make changes, to make sacrifices, that it was also massive corporations who were being dragged kicking and screaming to also make sacrifices, to also make changes, to also abide by new regulations that impacted their profits.

And that perception of fairness was absolutely critical in terms of people accepting the change. What we see in France with the gilet jaunes movement is that it is precisely the double standard, right, of seeing the tax breaks being given to big polluters and multimillionaires whose carbon footprints are sky high, while people who are already facing all of these stresses in a precarious economy are being asked to pay more.

I don’t think anybody serious seriously is saying voluntary lifestyle changes are going to do it. But I do think that you can make a serious argument that it’s important if you can, to change your lifestyle so that you can see and show others that actually it is possible to live well within our carbon budget. And that is an important kind of lived reality to be able to hold up in the face of all of this scaremongering that you’re going to get from the Fox Newses and all of the fossil fuel talking points that this is about just destroying people’s lives and so on, right. There are going to be sacrifices if we design this well.

We’re also going to have way better public transit. We can have better jobs and better working conditions, better services like for health care and education and a care economy. We can have a renaissance in public art. There are things that will improve. And yes, there are some things that will contract. We have to be honest about that.

Exit Polls Signal Setback for Israel’s Netanyahu in Election

JERUSALEM — In an apparent setback for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the longtime Israeli leader on Tuesday fell short of securing a parliamentary majority with his hard-line allies in national elections, initial exit polls showed, putting his political future in question.

Results posted by Israel’s three major TV stations indicated that challenger Benny Gantz’s centrist Blue and White party held a a slight lead over Netanyahu’s Likud party. However, neither party was forecast to control a majority in the 120-seat parliament without the support of Avigdor Lieberman, a Netanyahu rival who heads the midsize Yisrael Beitenu party.

Israeli exit polls are often imprecise and the final results, expected Wednesday, could shift in Netanyahu’s favor. But three stations all forecast similar scenarios.

Related Articles

Netanyahu Vows to Begin Annexing West Bank Settlements

by

Netanyahu's Miscalculations About Iran Will Cost Him Dearly

by Juan Cole

Netanyahu’s Partisan Streak Has Paid Off, But for How Long?

by

The apparent deadlock sets the stage for an extended period of uncertainly and complicated political maneuvering, but with Netanyahu in a relatively weaker bargaining position. The parties could be forced into a broad unity government that could push Netanyahu out.

Gantz, a former military chief of staff, has ruled out sitting with a Netanyahu-led Likud at a time when he is expected to be indicted on corruption charges in the coming weeks. Further complicating things, Lieberman refuses to sit in any coalition that includes religious parties that traditionally support Netanyahu.

Attention will now focus on Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin, who is to choose the candidate he believes has the best chance of forming a stable coalition. Rivlin is to consult with all parties in the coming days before making his decision.

Officials from both Blue and White and Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu both said they would seek a broad unity government.

“I want to lower everyone’s expectations. We aren’t going to join a narrow right-wing government or a narrow left-wing government,” said Eli Avidar, a member of Yisrael Beitenu.

The scenario would leave Netanyahu facing an uncertain future.

Netanyahu, the longest serving leader in Israeli history, had sought to secure an outright majority with his allies to secure immunity from the expected indictment. That now seems unlikely.

Throughout an abbreviated but alarmist campaign characterized by mudslinging and slogans condemned as racist, Netanyahu had tried to portray himself as a seasoned statesman who is uniquely qualified to lead the country through challenging times. Gantz tried to paint Netanyahu as divisive and scandal-plagued, offering himself as a calming influence and honest alternative.

After casting his ballot in Jerusalem, Netanyahu predicted the vote would be “very close.” Throughout the day, he frantically begged supporters to vote.

Voting in his hometown of Rosh Haayin in central Israel, Gantz urged all Israelis to hope. “We will bring hope, we will bring change, without corruption, without extremism,” he said.

The election marks their second showdown of the year after drawing even in the previous one in April.

At the time, Netanyahu appeared to have won another term, with his traditional allies of nationalist and ultra-religious Jewish parties controlling a parliamentary majority.

But Lieberman, his mercurial ally-turned-rival, refused to join the new coalition, citing excessive influence it granted the ultra-Orthodox Jewish parties. Without a parliamentary majority, Netanyahu dissolved parliament and called a new election.

The initial exits polls positioned Lieberman once again in the role of kingmaker. Lieberman has promised to avoid a third election and force a secular unity government between Likud and Blue and White that would leave out the ultra-Orthodox parties.

Another factor working against Netanyahu was that the fringe, ultranationalist Jewish Power faction, led by followers of the late rabbi Meir Kahane, who advocated expelling Arabs from Israel and creating a Jewish theocracy, failed to cross the electoral threshold. That dropped the support of Netanyahu’s overall right-wing bloc.

Netanyahu was desperate to secure a narrow 61-seat majority in parliament with his hard-line religious and nationalist allies, who were expected to approve legislation that would grant him immunity from prosecution.

Israel’s attorney general has recommended pressing criminal charges against Netanyahu in three separate corruption cases, pending a long delayed pre-trial hearing scheduled next month. Without immunity, Netanyahu would be under heavy pressure to step aside.

With his career on the line, Netanyahu has campaigned furiously and taken a late hard turn to the right in hopes of rallying his nationalist base.

He beseeched supporters to vote to stave off the prospect of a left-wing government he says will endanger Israel’s security. He has accused his opponents of conspiring with Arab politicians to “steal” the election, a message that has drawn accusations of racism and incitement.

In his attacks on Arabs, Netanyahu has made unfounded claims of fraud in Arab voting areas and unsuccessfully pushed for legislation to place cameras in polling stations on election day.

After Netanyahu’s proposal, seen as an attempt to intimidate Arab voters, was rejected, election officials barred cameras, including journalists, from all polling stations. In several cases, police blocked news photographers from approaching the stations.

Heavier turnout by Arab voters, many of whom stayed home in April, could hurt Netanyahu. After casting his ballot, the leader of the main Arab faction in parliament, Ayman Odeh, said Netanyahu was “obsessive” in his incitement toward Arabs.

Turnout emerged as a key element for this election day, which is a national holiday aimed at encouraging participation. In April, turnout was about 69%, slightly below the 72% figure in a 2015 election.

As of 8 p.m., Israel’s central election committee said 63.7% of eligible voters had cast their ballots. It marked a slight increase over the figure at the same time in April.

A centerpiece of Netanyahu’s eleventh-hour agenda has been the pledge to extend Israeli sovereignty over parts of the West Bank and to annex all the Jewish settlements there, something Netanyahu has refrained from doing during his decade-plus in power because of the far-reaching diplomatic repercussions.

His proposal sparked a cascade of international condemnation, including from Europe and Saudi Arabia, an influential Arab country that has quiet, unofficial ties with Israel. Jordan’s King Abdullah II said Tuesday the proposed annexation would be a “disaster” for the region.

The U.S., however, has had a muted reaction, suggesting Netanyahu coordinated his plan with the Americans ahead of time.

Netanyahu flaunted his close ties to President Donald Trump, who has promised to unveil a peace plan after the election.

Trump chimed in with his prediction, telling reporters at the White House on Monday that it “will be a very interesting outcome. It’s gonna be close.”

Netanyahu also claimed to have located a previously unknown Iranian nuclear weapons facility and said another war against Gaza militants is probably inevitable.

In some of his TV interviews, the typically reserved Netanyahu has raised his voice and gestured wildly as he warned of his imminent demise.

Oil Prices Ease on Hopes for Normal Saudi Production

DALLAS — The price of gasoline crept higher after a weekend drone attack devastated Saudi Arabian oil output, but if the disruption to global supplies is short-lived, the impact on the U.S. economy will probably be modest.

Prices spiked Monday by more than 14%, their biggest single-day jump in years, but retreated Tuesday, reversing some of the increase. U.S. oil fell nearly 5% to $59.96 a barrel, while Brent, the international benchmark, dropped 5.3% to $65.34.

A gallon of regular in the U.S. stood at $2.59 on Tuesday, up 3 cents from the previous day, according to the AAA auto club. Analysts warned that pump prices could rise as much as a quarter in the coming weeks, but it all depends on how quickly Saudi Arabia returns to normal production.

Related Articles

Yemen's Houthi Rebels Attack Key Saudi Oil Sites

by

King Salman Urges World Effort to Thwart Iran

by

Tuesday’s reversal in prices came as Saudi Arabia’s energy minister reported that 50% of the production cut by the attack had been restored. Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman said full production would resume by the end of the month.

Even before Tuesday’s reversal in prices, economists downplayed the prospect that the price spike could send the economy reeling. After all, Monday’s surge only put prices back where they had been in May.

The drone attack knocked about 5% of the world crude supply offline. Oil prices have been trending mostly lower since spring because of concern about weak demand due to slowing economic growth.

Analysts say oil prices did not fully account for the risk posed by tension in the Middle East, but they will now. Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen claimed credit for the drone strike on Saudi oil facilities, but the Trump administration blamed Iran itself. The attack exposed the vulnerability of Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure.

Higher oil prices mean more costly gasoline, and that will sap consumers’ ability to spend on clothes, travel and restaurant meals. It will hit people who drive for a living.

Brian Alectine, a New York-based driver for the ride-hailing apps Lyft and Juno, said a 5- or 10-cent bump in the price of gasoline wouldn’t be too bad, but an increase of 25 cents a gallon would make it hard to earn a profit after expenses, including the monthly rent on the car he drives for work.

“The more you drive, the more gas you use,” Alectine said. “It will have a big impact.”

AAA said the nationwide average price of gasoline could rise 25 cents this month. Patrick DeHaan, an analyst for price-tracking app GasBuddy, predicted an increase of 10 to 20 cents a gallon. He saw reports of price spikes and people rushing to top off their tanks.

“I’m not sure where this panic is coming from,” DeHaan said. “There will be an increase, but prices will still remain over a dollar cheaper than they were earlier this decade.”

Any drag on the economy from lower consumer spending would be at least partially offset by increased investment in oil and gas production, according to several leading economists.

Gregory Daco, chief economist at Oxford Economics, estimated that the net effect could be a decline of about one-tenth of a percentage point in U.S. economic growth, which was 2.0% in the second quarter.

“An oil price shock will weigh on consumer spending and will add a further strain on the global economy, but we’re not talking about a major price shock at this level,” he said, while acknowledging that the situation could escalate if tension increases between the U.S. and Iran — a major producer whose output has been greatly squeezed by Trump administration sanctions.

U.S. crude poked above $100 a barrel in stretches between 2011 and mid-2014, yet the economy did not fall into recession. Brent peaked above $140 a barrel in July 2008, which some economists believe was an overlooked contributor to the Great Recession, which is more often linked to a financial crisis and, in the U.S., a housing-market bubble. Brent more than doubled in a few months after Iraq invaded Kuwait, another large oil producer, in 1990.

The United States was far more dependent on imported oil in 1990. Saudi Arabia remains the world’s biggest oil exporter, but the United States recently eclipsed both Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s largest producer.

That makes the impact of higher oil prices on the U.S. economy much more mixed. Even as consumers and certain industries pay more for fuel, higher oil prices will be good for the U.S. energy industry and states where oil is produced, including Texas, New Mexico and North Dakota.

The stock market has highlighted which sectors will be helped or hurt by higher oil prices. On Monday, shares of oil producers surged, naturally, while stocks in airline, cruise and retail companies generally fell. Delivery giants UPS and FedEx dipped. They consume lots of fuel, and their business will suffer if higher energy prices cause consumers to reduce their online shopping.

For airlines, fuel is their second biggest cost behind only labor. Airlines were surprisingly adept at adapting to the last big run-up in fuel prices, but it takes them time to raise fares high enough to cover the extra cost.

American Airlines burned more than 4.4 billion gallons of fuel last year at a cost of nearly $10 billion, including taxes. On Monday, its shares fell 7.3%, more sharply than other carriers. Unlike most others, American doesn’t buy derivative investments as a hedge against fuel spikes, and its relatively heavy debt load leaves it vulnerable if the economy slows for any reason, including a jump in energy prices.

American estimates that over a full year, each penny increase in the price of fuel costs it $45 million. The price went up about 15 cents a gallon over the weekend.

If the fuel price increase persists for even a few weeks, analysts said, it could cause airlines to rethink their aggressive growth plans for 2020.

Ryan Sweet, an economist at Moody’s Analytics, said U.S. consumers are in good shape to handle a temporary increase in gasoline prices — with some savings, a tight job market and accelerating wage growth. Consumer psychology, however, can be difficult to predict.

“I don’t think this increase in oil prices … would be enough to single-handedly tip us into a recession,” he said. “The one cause for concern is that the consumer is carrying the economy. If the consumer starts to pack it in, the recession odds increase quite significantly.”

___

Associated Press Business Writer Cathy Bussewitz in New York contributed to this report.

The Health Care Industry Poses an Existential Threat to the Middle Class