Meg-John Barker's Blog, page 13

September 4, 2019

Sexual incompatibility

I was recently included in this article about sexual incompatibility by Alix Fox. It’s something that Justin Hancock and I talk about regularly on our podcast as we think that the myth of easy and ongoing sexual compatibility is one of the reasons people are often so unhappy and anxious about their sex lives. Here’s my answers to the questions Alix asked me.

What are the most common kinds of sexual incompatibility?

Probably the most common ones are people having different levels of desire or wanting different amounts of sex, and people enjoying sex for quite different reasons (e.g. for one it is to feel connected with a partner, for another it is more about the release of orgasm, or being in certain roles). People just being into quite different things is also common: like one being more kinky or open than another.

Do you think absolute incompatibility is a myth and that most people can learn to satisfy one another? Or are there problems where it’s more sensible to break up, or accept it the way things are?

I would challenge the stay together / break up binary here! In any relationship there are bound to be areas of compatibility and incompatibility (around all kinds of things, not just sex). It’s useful to view it as a Venn diagram. What is in your separate circles and what’s in your overlap? The main problem is that people are taught that they shouldn’t have any incompatibilities and that The One true partner should meet all their sexual needs and desires.

[image error]

If we see incompatibility as inevitable we can remove some of the shame and start to think creatively about which desires we might explore together, which we might explore separately and how (given the agreements that we have around non/monogamy). Justin and I have produced zines on making your own sex and relationship user guides to help you to have these conversations.

What are the ways people can approach incompatibility issues in terms of practical actions and strategies?

First it’s worth thinking about your non/monogamy agreement. In your areas of incompatibility where is it possible for each of you to get those desires met? If the relationship is sexually monogamous then ensuring time for separate solo sex, reading/writing erotica, watching porn, fantasy, etc. is important. If non-monogamous then might these desires be met with another partner, in hook-ups, with a sex worker, at parties, or in other ways?

If one person wants sex a lot more/less than another, or this changes over time, try to expand your understanding of what ‘counts’ as sex. Make a long list – separately and then together – of all the erotic and sensual things you might enjoy together and then find out which ones you both enjoy. Create times together to enjoy those things so that there isn’t pressure in those times to have the kind of sex that the one person doesn’t want. Consent-wise you should only be doing what you are both a wholehearted ‘yes’ for. Ensuring that the times you do connect together are consensual and enjoyable for everyone involved will help a lot.

When one person has a fetish the other does not share, dig into what sex – of various kinds – means to each of you. What is it you’re looking for from sex? What kind of feeling do you want from it? What is enjoyable about it for you? This kind of conversation can be very illuminating and help you find the common ground as well as the areas where you differ.

If a partner doesn’t seem to know how to touch you, or how they want to be touched, it could well be worth going to some events together where you can learn more about sex, and/or doing some reading. Barbara Carrellas’s Urban Tantra and Betty Martin’s Wheel of Consent both offer brilliant advice about how to learn to be with your body and another person’s body, learning what you enjoy giving and receiving, and how to be present to each other during sex.

If you are both dominant/submissive – if you’re non-monogamous and you want to be erotically connected, what about finding a third person or people who you can co-top – if dominant – or submit to together? Or you could each get those desires met elsewhere and connect over comparing notes. Sometimes we can find hidden submissive sides (if dominant) and vice versa, so it might be worth playing with that very gently and cautiously to see whether you can switch, but if that doesn’t work for you that’s just okay.

If one person wants sex to be tender and emotional, whereas the other has a more casual or raunchy attitude to sex, again digging into the meanings of sex and the reasons for having sex for each of you would be useful. Perhaps there is some common ground. If not then it’s fine that you have different desires. Can you reconfigure the relationship so that it is grounded on other things than sex and go elsewhere for the sex?

If your partner doesn’t instinctively seem to be able to ‘read’ you, this is another good one for reading or going to events and learning each other. It’s also just okay if you find that sex isn’t one of your areas of compatibility and you need to go elsewhere for that and base your relationship on other things.

Are there any additional approaches or ideas you can detail that can help people bridge sexual gaps and find greater satisfaction with one another? e.g. sex menus, being ‘GGG’, scheduling sex, getting therapy, etc.)

Sex menus are great. Check out Enjoy Sex and megjohnandjustin.com for more about how to talk about sex, be present to sex, and figure out what you want.

GGG and scheduling sex risk being a fast-track to non-consensual treatment of yourself and the other person. Never have sex you don’t want! It is fine to get your sexual desires met somewhere else. It is fine to have a close relationship which is based on other things than sex. Most partners have incompatibilities. Many long term relationships become non-sexual and that is fine. If you have unwanted sex you are hurting yourself and you are likely to want even less sex as a consequence. Please don’t do this to yourself!

How important is it to solve sexual incompatibility? Is it possible to have a happy, healthy relationship without mutually satisfying sex?

It’s totally possible and very normal. The Enduring Love study found that many – if not most – long term couples had happy relationships without much sex together. The myth of one relationship meeting your sexual desires for a lifetime is really dangerous.

The post Sexual incompatibility appeared first on Rewriting The Rules.

September 2, 2019

Queer mad comics

Earlier this summer I was stoked to keynote the Graphic Medicine conference whose theme this year was Que(e)rying Graphic Medicine. My talk was called ‘queer, mad comics’. Graphic Medicine have recently published a podcast of the talk, along with some of the images I used in the presentation, over on their website. This post contains a summary of the talk and some of the comics that I used in the presentation.

I’d heard of the Graphic Medicine conference before but had assumed that the ‘medicine’ in the title meant that it was mainly for doctors, nurses and other medical types. Actually the event – and the community around it – are for anybody who works at the intersection of comics and health of any kind. So there were many creators there who use graphic memoir or comics to depict their experiences with disabilities or physical and/or mental health struggles. There were also academics, activists, and practitioners who are interested in creating comics and zines to raise awareness of particular issues, or in analysing work which is already out there on these themes. I met some incredible people and saw some powerful presentations. I’d encourage you to check out their website and follow them on to find out more.

The conference organisers invited me because they were familiar with my book Queer: A Graphic History. Like me, I think they got more than they bargained for because they hadn’t realised that I’ve also created comics and zines to explore mental health struggles: both from a personal exploration perspective, and to raise awareness or give others tools to do this kind of work.

I’ll give a brief overview of the talk here. You can check out the full podcast if you want to hear the more detailed version. I’ve also been writing more lately on plural selves in relation to queerness, mental health, and comics, which I’ll be sharing here soon.

My history with comics

I started the talk by reflecting on my own history with comics and how this was interwoven with gender, sexuality, and mental health. In childhood comics were a place of safety to retreat to alone when outer relationships became traumatic.

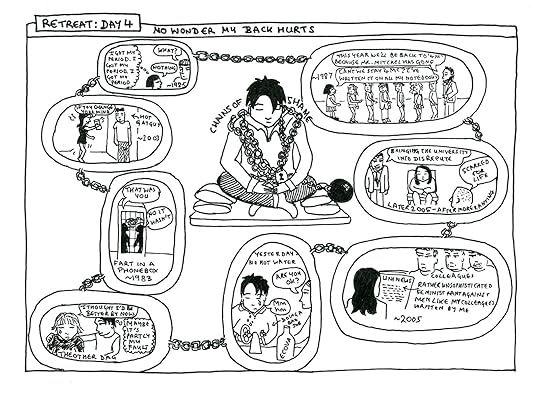

[image error]My history with comics: Early days

Girls comics were one of the key places where I learnt very gendered scripts about how to perform femininity, at the same time as being a place of some resistance to this as I followed my love of horror comics.

[image error]My history with comics: Gender

When I discovered graphic novels this rekindled my passion for comics, and they became a place where I learnt about queerer ways of doing gender, sexuality, and relationships, as well as a sanctuary during tough mental health times.

[image error]My history with comics: Graphic novels

I reflected how, these days, my favourite genre of comics is memoir, particularly queer and mental health graphic memoirs. It’s interesting how many graphic memoir authors focus on stories of queerness or mental health, and how often these overlap. Many mental health comics also depict people and relationships which are queer in some way, and many queer comics also cover mental health struggles, perhaps understandably given the extent of trauma inevitably involved in growing up queer in a heteronormative world. More on queer comics here.

Using comics in my work

In the presentation I spoke a bit about how I’ve incorporated my own comics into book projects like Rewriting the Rules and Mindful Counselling and Psychotherapy. Largely this was out of necessity because there was no money available to pay illustrators. For the mindfulness book it also felt important to include something which got across the lived experience of mindful meditation – which is very different to the shiny panacea offered by many advocates of mindfulness. Comics can often be a more powerful, visceral, way of depicting lived experience than words or pictures alone.

Mindfulness comic

Mindfulness comicImportantly these comics also depict the link between cultural scripts of gender and sexuality and mental health struggles as a biopsychosocial experience.

Queer, gender and sexuality

In the talk I gave a brief introduction to queer thinking based on Queer: A Graphic History. I explained how queer theory and queer activism emphasise that our lived experience occurs within a historical and social context. We’re massively shaped by cultural messages around who is more or less normal, and social structures that uphold this. We can’t disentangle our lived experience from wider culture.

Also queer thinking points out that our identities are not fixed or singular but fluid and plural, in terms of sexuality and gender but also more widely than this.

I spoke a bit about projects where I’ve used comics and zines to help people to explore these kinds of ideas in relation to gender and sexuality, in the form of workbooks. Jules Scheele and I also have new graphic guides coming on the themes of gender (2019) and sexuality (2020). Jules also included my first published comic in this zine on performance.

Mental health

Back in 2015, Caroline Walters, Joseph de Lappe and I put together a special issue of Asylum magazine on comics and mental health. Our call for submissions prompted so much interest that we ended up taking over four issues of the magazine with comics. Many people found that reading and/or creating comics was very helpful in relation to their own mental health, and to surviving toxic wider cultures, and mental health institutions. You can read more of my thoughts on this in this article I did for The Psychologist.

[image error]Depression

A big part of my work now involves making comics and zines relating to mental health. These take the following overlapping forms:

Comics and zines which raise awareness and provide tools for people to address aspects of their own mental health, such a staying with feelings, self-care, or exploring sex and relationships.Comics and zines which depict my own lived experience in ways which are personally therapeutic.

From a queer perspective most of this work/play makes explicit links between wider cultural normativity and mental health struggles. It also often plays with the queer theme of identity as fluid and plural. Many of my comics involve time-travelling back to communicate with earlier versions of myself, or shape-shifting between different sides of myself in order to bring them into communication. I’ve written on here before about trans and queer people as time-travellers and shape-shifters, and what can be gained from these ideas for everyone.

After the conference I was invited to submit a paper to a special issue of the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics on sexuality and mental health. Hilariously having just left academia and vowed to write no more academic papers here was an invitation I couldn’t refuse, and I think it’s one of the best academic articles I’ve ever written! I focused on plurality and how this relates to gender, sexuality and mental health, as well as this theme of how comics can help us to explore plurality via time travel and shapeshifting. More on all of that soon…

If you enjoyed this, listen to the whole talk here.

The post Queer mad comics appeared first on Rewriting The Rules.

August 28, 2019

Embracing failure in work, home, and relationships

Long read ahoy, all about failure. For the takeaways feel free to skip to the end.

This summer I left employment – and education – after over two decades, to focus on writing full time. It’s a curious way to celebrate it: writing about being a failure. But it’s been such a major theme of the past year that it feels like the best way to do so.

Over the last year I’ve failed repeatedly. My favourite author and teacher, Pema Chödrön, wrote a book called Fail, Fail Again, Fail Better which I’ve been reading a lot of late. I’m not sure that I’m failing better yet, but I’m certainly becoming very well acquainted with failure and what it has to offer us. If that sounds like a strange idea – surely failure is something to be avoided – then keep reading.

My great mate and co-author Justin Hancock says that we can generally handle it if one of three areas of our lives – work, home and relationships – is shaky, so long as the other two hold relatively steady. If two of those aren’t good then things start to feel pretty precarious. And when all three go at once…

That’s what happened for me last Summer. I was starting the process of leaving academia so work was shaky, I was moving city and it took a good while to figure out where I’d be living, plus things were rocky in my relationships. This was all against the backdrop of it finally really hitting me what it means to be a trans person at this cultural moment of moral panic; a survivor during #metoo and all the conversations that have followed, and recognising how intertwined those things are with my life and my work.

Still, I landed, I found a sense of relative safety, and I managed to keep going, albeit at a much slower pace and with a lot more emphasis on self-care than before.

But now I actually have left my employed job after a whole life spent studying or working in education. Having thought I had a handle on it, I’ve fallen back into my old relationship patterns more than once in the last year (like a hamster on a freaking wheel!) and I’ve had to painfully confront the impact that’s had on myself and others, with a whole lot of regret and loss in the process. And, just when things were at their worst, I found out that I couldn’t stay living in the place that had become home for me.

Approaching Failure

I’ve been through these kinds of failures before. I’ve lost several jobs, homes, relationships, friendship groups, and communities along the way, often under painful circumstances that have left me feeling shame at having let others – and myself – down. The shift this time – I hope – isn’t that I’m not failing, it’s that I’m trying to approach failure in a radically different way.

Authors like Pema, and Brené Brown, who write about failure point out that failure is inevitable in life. This is particularly the case if you are ‘in the arena’ – as Brene calls it. Doing what feels valuable in work, love, and community is inevitably also going to be vulnerable. And we’re inevitably going to fuck it up at times.

Because of the stigma around failure, most of us endeavour to avoid it at all costs. If it happens we respond by blaming ourselves and hiding away so we never risk failing again, or by blaming everybody else and not taking any responsibility for what we’ve done because it’s too hard to face our shortcomings and limitations – and their impact. When I failed in the past I often burned my bridges pretty fast, moved on, and worked even harder to avoid such failure in the future, without looking too carefully at what’d just happened.

What I’m doing this time is different. I’m trying to embrace the fact that these failures have happened – and that they certainly won’t be the last ones I experience (well so long as I stay alive of course). Instead of adding them to a long list of past experiences that have felt similar – and using them as proof of the story that something about me is wrong and unacceptable, or that there’s something wrong with the work, people or communities I’ve surrounded myself with – I’m trying to look at them clearly, with honesty and kindness.

When I do that I realise that there’s much to be learnt here – probably far more than we learn from experiences of ‘success’. Also, the closer I look, the more the success/failure binary is called into question. I see that these two elements are closely woven together – inseparable in fact. As Brené points out: learning, creativity and innovation aren’t possible without failure. But I think it’s more than that: failing at work is a kind of work (perhaps this kind of work that I’m doing right now!) Also, failing at love and home have both brought me as much love and home as they have lost me.

Let’s delve deeper into these three areas so you can see what I mean…

Work

I’m a failed academic. Clearly. I’m 45 and I haven’t made professor: the pinnacle of the academic ladder. This is because – despite publishing twenty books and over a hundred articles – I have never been REF-able: The Research Excellence Framework which is the way academic success is measured in the UK.

I’m not excellent. Far from it. I haven’t brought in research funding because I didn’t want to spend my time on funding bids or administrating big research projects. Also, every time I thought I’d finally written something that ‘counted’ as the right kind of academic work, I was told that it still wasn’t right: too ‘polemic’, too far out of my discipline (undisciplined), a chapter when only journal articles counted, a theory paper when only research papers counted, a co-authored paper when single author is the gold standard, single author but not in the right kind of journal, in the right kind of journal but not the right kind of research.

I tried to carve out a different path as a public engagement academic, but it’s not enough to do that alone – you do need to bring in the money and publish the papers also. When you point out that it may well not be possible to do all of those things, teach, and practise self-care – and care for the others in your life – that doesn’t tend to go down particularly well.

I could say a lot about which kinds of people academic systems and structures do – and do not – serve; about the kinds of labour, knowledge and bodies that are – and are not – valued there; and about the impact this has: the shame, imposter syndrome, and anxiety that so many academics are plagued by. I probably will say more about these things at some point. And I should also acknowledge the massive privileges I’ve been afforded by being within academia (and being privileged enough to get there in the first place): the money I’ve been able to save, the things I’ve learned, the projects it’s supported, and the ways it’s been (mostly) a safe-enough place to be my particular brand of non-normative weirdo. For now let’s agree that I’m a failed academic, by academic standards.

It’s okay though, I never actually wanted to be an academic. I only did a PhD in the first place because I was too young to do the thing I really wanted to do which was to be a therapist. And I only took an academic job post-PhD to fund my therapy training. I stayed in academia because I got passionate about teaching, and about studying the things I care about as an activist (gender, sexuality, relationships, mental health). But really I always wanted to be a therapist.

Here’s the thing: I’ve failed at that too. I worked as a therapist for over a decade – mostly in voluntary contexts because I had the academic job to pay the bills. Last year I left the voluntary therapy behind with the plan that I’d take on more private clients, so that I could afford to live once I quit the academic job to focus on writing. I didn’t take on any more clients. I realised that not being a therapist felt like a relief. My reservations about therapy in general – and about my particular capacities as a therapist – surfaced, and I realised that I needed to stop. So I did, with no idea about what I was going to do for money if I wasn’t going to do that.

It’s a good thing too because I would not have been able to hold therapy clients through the last year, given the crises I was facing in my own life. But it’s not just that. Being a therapist isn’t for me, I realise. I’m not the kind of therapist I would want to be: the kind that I’ve been lucky enough to experience a few times in my life. I don’t have that skill set: the capacity to contain people, or to work with them relationally in the ways I’d want to. I can do great one-to-one work with people, but in much more of a peer-to-peer mentorship type way. Not therapy.

But this is all okay because the whole point was that I was giving it all up to be a writer, right? So that’s what I’ll be: a writer. D’you want to know how much I wrote – for publication – between last summer and this? Zero. Nothing. Not a word! The stuff I have coming out this year was all written before then. I have written thousands and thousands of words in my journal. I have written the third book in the four-book erotic fiction project I have going on, which may never see the light of day (the prospect of putting something that vulnerable out there and failing remains too scary, but who knows?) I managed the odd blog post, but even those were few and far between.

What did I achieve – workwise – in these months of failure? A lifelong workaholic I finally learned how to underfunction instead of overfunctioning. I learnt to prioritise self-care: always putting The Work before the work. I largely undid my previous patterns of working to soothe or distract myself, or getting through the to-do list before I allow any self-care. I learnt to relate to work consensually: to feel into my body when I get a request, and to only say ‘yes’ to things that feel good immediately and still feel good 48 hours later. It’s been hard and it’s been messy, like all change. I’ve let people down. I’ve felt like the flaky colleague just when I wanted to end on a high note. I’ve taken time off sick when previously I’d have worked on through. I’ve had to go back to people when I’d said ‘yes’ to change it to a ‘no’ when I realised I’d overridden my self-consent.

It’s still a work in progress, but it is The Work: changing the habits of a lifetime of remaining in sometimes toxic and bullying work environments, forcing myself to produce the kinds of things I thought would count rather than what I valued, working through crises, sickness and struggle instead of allowing rest, recovery, recuperation. Writing is coming back now (as evidenced by the sudden explosion of blog posts and tweets about my new graphic guide). What I’ve been through is helping me to keep remembering to engage with writing more kindly, openly, mindfully, and flexibly. I’m pretty convinced that when we write in such ways it’s better quality – and connects more with others – too.

Home

To relate very differently to work – prioritising the work I find most fulfilling and feel most skilled at – requires rethinking home too. How to live in order to be a full-time writer, because sadly writing alone will never provide a liveable income for most of us? Twenty books in and only one of them brings me in more than a few hundred quid a year – and that may only be for a short time.

The main answer is, again, privilege. My whiteness, financially comfortable background, being largely non-disabled within our current society, location in the UK with English as my first language, and more, meant that I had enough privilege to access higher education. Also, remaining in higher education meant that I had the kind of job where it’s possible to be pretty crazy and pretty weird and still keep a paying job (except for that one faily, faily time when I nearly got fired after The Sun called me a bisexual boffin). So – despite a relationship pattern where I’ve given a lot of the money earned through this work to other people in order to secure love (top tip fellow people pleasers: it doesn’t work) – I managed to save up enough to live on for a while, now that I’ve downsized considerably

While I was searching for somewhere cheap to live an opportunity came up to live in the co-op my friend lived in. I’ve loved the idea of communal living since I came across Tales of the City at a formative age. I did have some assumptions and fears about what it might be like in practice, most of which were wholly inaccurate. It seemed like a financially sustainable option outside of the problematic systems of renting and buying property. I also loved the possibilities it opened up around access intimacy, care, and consent.

Living there I learnt lots about how much more possible self-care becomes when we have systems and structures which support it. I also learnt how much more possible caring for each other through physical and mental health struggles is when there are many people around and available, all of whom get it. I saw how conflict – openly addressed and held within family and community – can play out differently. I also learned some hard lessons about group dynamics. I’m sure I’ll be reflecting on this experience for many years to come.

But when the house considered whether to make me a permanent member after eight months they decided not to. Partly this was because I had been going back and forth a lot about what my ongoing living situation would be. But more than that – and this was bloody hard to hear – it was because I felt to them more like extended family than immediate family.

It would’ve been so easy to experience this as rejection, as me failing. The day it happened I was awash with memories of previous experiences that felt like this: when my university housemates threw eggs at my door because they were so sick of me having my depressed partner round at our flat all the time; when I lost most of my group of friends following one of those painful periods of ricocheting break-ups that can happen in queer community.

Partly thanks to the work the house has done in holding people through conflict and crisis – and perhaps also thanks to The Work that I’ve done over the years – this played out very differently. I was able to feel the feels and to express them – quite vividly – to everyone, and to feel heard and seen and understood. And I was able to hear them too. They were right that I felt more like extended family: I felt that too. And while it was terrifying to have this final rug pulled out from under me at this exquisitely vulnerable time, there was a sense of possibility in it too: things that might open up as well as close down.

Interestingly, since that time and in the conversations we’ve continued to have, I’ve actually felt closer to my friends from the house – not further away. There’s been a lot more openness. And I’ve been able to put more time and energy into nurturing other friendships where I have deep connections, including sharing my new home space with them in ways I never did before. I’m able to hold the possibility that, in losing a home and family, I may paradoxically have gained one.

Feeling Failure

I realise at this point that I’ve been talking about failure in quite a prettied up way: the way it can look in the fuzzy glow of hindsight. You could go away with the impression that it’s this okay thing – not that bad – quite beautiful in fact if looked at from the right perspective. Let’s talk about what failure actually looks like. Let’s talk about what it feels like.

Brené likens it to stepping out into the arena and falling on your face, eating dirt in front of everyone. It is like that. Except imagine that you’re naked. Not noble Cersei Lannister kind of naked but crying, begging, and scrabbling at the door you’ve just been pushed through to get the hell out of there kind of naked. There are tears and snot, there is rage and terror. It’s not a pretty sight. And scrutinising your every move are all your closest friends and family, plus everyone who has ever bullied you or criticised your work, definitely all your exes and your scariest school teachers. And every single one of their faces is filled with disgust. And they are just about to release the terrible monster that you have to fight. And when they do there is every fucking chance that you will crap yourself from fear in front of everyone. That, my friends, is what failure feels like.

That’s how it felt when those eggs hit my door, when I saw that headline in The Sun and had to face my managers afterwards, when I felt rejected from my community and slunk away, when I tried to bring my soft consent-y activism into my workplace and everybody looked at me like I was completely crazy, when the house gave me my notice. And that is precisely how it’s felt every time I’ve tried and failed at love, especially during the period where I’m desperately flinging everything that I have at it, trying to pretend that I’m not doing the same old thing again like the aforementioned hamster.

Relationships

I’ve already said most of what I need to say about my relationship patterns in the second edition of Rewriting the Rules, and in these blogposts. Sadly that hasn’t stopped me from finding thrilling new ways of acting out the same old patterns: struggling to be honest with myself and others, striving to meet others’ expectations, or assuming they will be on the same page as me. This was a big part of the dynamics that brought three of the relationships – with individuals and groups – that were most important to me to breaking point in the last year.

Understandably, failure cuts deepest for me when I’m failing in this particular arena. Being somebody who has written several self-help style books on relationships really doesn’t help with that. At least I make it very clear in my writing that this stuff is bloody hard for all of us – so-called relationship ‘experts’ included. Perhaps I should insist on being billed as a relationship failure from now on.

However, I’ve noticed that, as with work and home, there is a lot of love to be found in failing at love. These days my go-to response to a life crisis is to book in time with close people each day until I’m steadier – online calls or in-person walks and talks – in addition to ongoing message exchanges. During these conversations it’s been reaffirmed for me that intimacy deepens with vulnerability. I’ve shown my feelings, my insecurities, more openly than ever before and I’ve felt how much closer that’s brought me to my people. Also most people have shared their struggles right back.

I feel more able to be real with my people – instead of monitoring myself and keeping up a facade – and I feel more able to connect with them too. How paradoxical and wonderful that mulling over the potential impossibility of love has resulted in such strong feelings – and actions – of love.

The other thing that I’ve made into a daily practice of late is explicit internal conversations. Anyone familiar with my work knows that I’m big into the idea of plural selves, and I often experience myself as more of a team – or a system – than an individual. So most days start and end with a check-in between the members of this team – written in my journal – with the explicit intention that the parts of me who are struggling will support the parts that aren’t so much on that particular day.

In Rewriting the Rules I suggested that experiencing ourselves as plural could make it easier to love ourself than it is when we imagine that we’re this singular, static individual who can be judged as good or bad. That’s certainly been my experience of late. There’s a lot of love within for the vulnerable parts, the parts who fought so damned hard and still managed to fail, the parts who took the risk and now find themselves exposed in the arena.

Embracing and Learning from Failure

This blog post is already over 3000 words long: another failure. I rarely manage the SEO-pleasing 500 word shorties that experts recommend. WordPress will doubtless give me a bunch of angry red emoticons for this latest opus and for my continued use of the passive voice.

So what are my quick take-aways about failure then, other than what doesn’t kill you makes you stranger?

Failure is an inevitable part of being human, get used to it, and go gently because our whole culture tells us that it’s not okay, that we’re to blame for it, and that we should punish ourselves for it.A sense of failure may be more about you not fitting the particular system or situation you’ve tried to succeed in. Moving into a different system or situation – perhaps one with values more aligned with your own – might be something to explore.Feeling you’ve failed at something can give you an opportunity to stop doing that thing. The space that opens up may bring something different that you end up finding more fulfilling and feeling more competent at (like me replacing therapy with writing mentorship).Failure shows us where we’re stuck, where we’re hooked, where we’re messy. Learning these things is super helpful because then we can work to shift our patterns (again, gently please).Failing in different arenas can actually bring us the very things we thought we were losing from failing. Failing at work can become a big part of our work (emotional, creative, and otherwise – like all the people who make their work out of helping people who are struggling in the same ways that they have). Failing at home or family can bring us other forms of community and kinship. Failing at relationships – and sharing our experiences around this openly – can bring us love and connection.If you can stay with the fact that you’ve failed – and the impact of this on you and others – it can make you a lot more humble and compassionate for others caught in the same kinds of situations and dynamics.As Brené Brown points out, remaining in the arena even when we know the risks of failure – and what it feels like to fail – is pretty badass. Think Captain Marvel standing up again each time she gets knocked down in the movie.As Pema Chödrön suggests, having the rug pulled out from under us completely can be just what we need in order to stop looking for babysitters to look after us, and to start opening up to what life has to teach us.As queer theorist like Jack Halberstam and Sara Ahmed point out, what is considered successful in our culture is often determined by those with the most power. The more non-normative we are, the more likely we are to fail according to the normative standards of what counts as success. So failing can be seen as a radical part of resisting these norms. And we can rightly get pretty pissed off at how we’re set up to fail by norms which require us to pass exams, make lots of money, own property, ascend various professional ladders, stay in particular kinds of relationships, look attractive according to western beauty ideals, have kids who also meet these criteria for success, etc. etc. etc.

Okay that wasn’t so quick. Let’s try again. What can you do if you’re struggling with failing and failing again. I’d say the important things are to:

Practice self-care around it. If it feels overwhelming then first focus on getting yourself back to a safe-enough state to look at it. Refrain from doing anything till you’re in a good-enough place to deal. There’s no rush.Stay with the feelings.Try to see the failure clearly, honestly – and above all – kindly.Consider what it would be like if we could see the faily parts of us as the most precious, tender, and loveable parts of us. Wow right?Focus on addressing your part in what happened – it’s up to others whether or not they want to address their’s. Also recognise the wider dynamics, systems, and structures that are in play which mean it’s not all on you. Try not to be drawn into blame and shame, and go easy on yourself when you’re inevitably drawn into blame and shame.Question the success/failure binary and who this serves.Recognise that habits take time to shift and require repeated failure in order to do so – check out this poem by Portia Nelson to help with this. It’s okay that you fell into that hole again.Don’t listen to criticism from people in the cheap seats. They aren’t in the arena, as Brené says. But do welcome generous feedback and support from people who have your back and are up for facing their own failure. This is not something we can do alone.Let failure crack you open, soften you up, connect you with others who’re going through similar stuff, and fuel your creativity.Try not to be part of cultures which shame people for failing, making it even more difficult for all of us to accept our inevitable failures, to take responsibility for their impact, and to fail better.

I’ll leave the last word to Thor’s mum, Frigga, in Avengers Endgame because I liked this thought on failure: ‘Everyone fails at who they’re supposed to be. The measure of a person, of a hero, is how well they succeed at being who they are.’

The post Embracing failure in work, home, and relationships appeared first on Rewriting The Rules.

August 21, 2019

Showing Your Working: On Writing Vulnerable

Now that I’m a full-time writer (yes, I did it!) I’m thinking even more than I did before about the process of writing. Something that comes up a lot around my own writing – and in my work with clients as a writing mentor – is vulnerability. I shared a post last week that was pretty vulnerable in terms of content, so I thought I’d follow up with one about the process of writing and sharing vulnerable work. I’m guessing that a lot of the stuff that I cover here will also apply to other forms of creativity too.

Writing is a vulnerable act. This is one of the many things that it has in common with sex (which needs to be the topic of a whole further blog post). When you write, you’re putting yourself out there – exposed. Even people who are doing pretty safe forms of writing – where there’s nothing personal in there and where every statement is backed up with facts and figures or references to other peoples’ work – still feel massively vulnerable. We’re scared of getting it wrong, we can easily imagine every possible critical comment, we fear being ‘found out’ in relation to how little we know and/or how poorly we write, we compare ourselves to other writers who we admire and we can’t possibly measure up because our voice is not their voice.

Writing about vulnerable stuff

How much more vulnerable then when we’re writing about things that we, ourselves, feel vulnerable about. I felt that heavily last year when I was finishing the writing for my new graphic guide on gender. It struck me just how much of what I was writing about was deeply personal and painful: Writing about trans during the trans moral panic; about #MeToo as a survivor; and about intersectional feminism when I’m so aware that I’ll inevitably perpetuate the very systems I’m challenging at times, because of the things that I don’t see in the areas where I’m privileged.

And then there’s writing more directly about our personal lives. This has come up with several clients lately. One worries that describing his daily moments will be read as egocentric – that it’s not doing anything for anybody else – even though it’s the writing he feels so passionately drawn to. Another fears what limits may be put on their activism, or their future career, if they write as openly about their own experience as they’d like to. I’m surprised when another client doesn’t see the link between the memoir-style posts that they write, and the writing that I do. I feel like my own vulnerabilities are starkly apparent in much of what I write, but perhaps the critical self-help style that I generally use obscures them somewhat.

The challenge from that client spurred me on to publish a few of the more vulnerable blog posts that I’ve been holding back on: ones that are more directly related to my own life and my own struggles. I put one out there last week. The feelings on publishing a more personal post always follow a familiar path. First a fizzy nervous feeling: ‘did I really do that?’ Then a fear of negative repercussions. Then a few comments come back: people saying that they connected with what I wrote, that it was just what they’d needed to read on that particular day, that they share that experience and it left them feeling less alone, that it helped them to reflect on their own lives. Those comments help me feel less alone and more connected right back. And I’m reminded that it’s nearly always the more vulnerable things that I write that get that kind of response.

I’m reminded of something Mollena Williams-Haas said in this talk: How creating from our most vulnerable places often leads to the best work we can do – for ourselves and for each other. It’s often higher quality, connecting creator and audience on a more visceral level, and it’s one of the best ways in which we can be of service to our communities. I love the way that Mollena links submission to vulnerability to activism in this way, it’s something that resonates deeply for me too. In fact that talk is an excellent example of what I’m talking to because she went for the vulnerable, open approach – weaving together the erotic and the creative – and it spoke to me so much that I remember it to this day.

Showing and telling

One of the classic pieces of advice to aspiring fiction writers is ‘show, don’t tell.’ Readers don’t want to be told the main character is a cocky piece of work who hides an inner vulnerability, they want to see that from the way he strides across the bar in the first scene, oh-so-casually glancing around to check that everyone is clocking him.

So is there a value to showing rather than telling in non-fiction too? I guess the writing that I do which I experience as most vulnerable is the stuff where I show my workings, rather than just telling the reader that this is something I struggle with too.

When I first wrote Rewriting the Rules the main place that I did this was the conflict chapter. I illustrated that with a detailed description of the kind of excruciating conflicts that I’ve had in partner relationships. In the second edition I added much more detail about my own relationship patterns in the love chapter, in order to demonstrate how these come from a combination of wider cultural messages, and our own lived experiences growing up with these messages all around us.

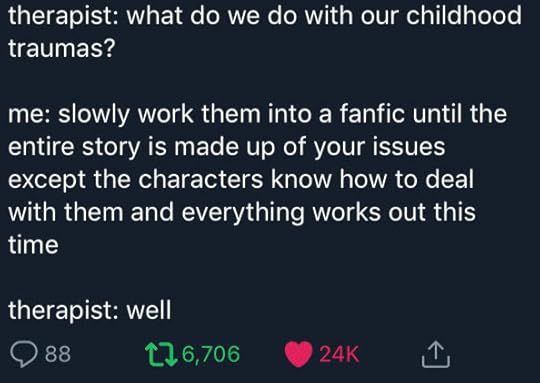

Nowadays I do a few kinds of vulnerable writing. I write more memoir-style pieces where I reflect on something I’ve been through, or am personally struggling with, or attempting to put into practice at the moment. I write fiction which is well summed up by this person on twitter.

I also create comics and zines about aspects of my experiences.

Generally I use the personal sharing I do in such writing as an example: this is how you could do this kind of work, this is how you could understand how our experiences shape our habits, here’s a practice you might try. But sometimes I let the showing stand alone. Perhaps there’s not always the need to tell as well as show.

When is vulnerable too vulnerable?

This is complicated territory because writing from the vulnerable place is also risky. You could end up hurting yourself by trying to write about something which is still too raw and painful. The writing could stray into something over-sharing or self-focused in a way that doesn’t really connect with others. This is particularly likely if you’re still very caught up in the details of what happened in that particular situation. It could feel too vulnerable if people respond critically to it once you’ve put it out there.

There’s some kind of balance to be struck between the value of writing about what’s live when it’s live – the authenticity and sense of aliveness that kind of writing can have – and the wisdom of knowing when something needs more time before you approach it creatively – either in order to be safe enough for yourself, or for it to take a form that others can connect with.

On our podcast Justin and I often come up with ideas we’d love to cover but they feel too live for us – or for others in our lives – at the moment. We keep a list on our phones of topics that would be great to cover, but we want to come back to them when it feels like we have a bit more distance from them ourselves.

Another thing I do is to journal about the things that are really live initially in a format which is not for public consumption. I’ve filled hundreds of pages in the last year, going through major transitions in work, home, and relationships. Many of the ideas and practices that have come out of this writing will likely eventually find their way into my non-fiction and fiction writing, but it’s probably best that the writing I do for the initial processing is for my eyes only.

There’s an inner sense of ‘not ready’ and ‘ready’ which I’m beginning to trust in this – and other – aspects of life. For example, there will hopefully eventually be seven comics in this series, but this is the only one that’s felt complete enough to get down so far.

If something starts to take shape as a piece of writing for a reader beyond yourself you can always write it when live and return to it later. It’s a great idea anyway to separate the writing process and the editing process. This means that in the first drafting you can really sink into the flow and write it however it comes, knowing that you’ll be coming back to it before it goes out anywhere, so you can free yourself up to make mistakes and be imperfect. This is what Anne Lammot calls the ‘shitty first draft’ – something we’re allowed to do in writing and in life.

Personally I find it helpful to have a notepad or extra document open alongside my writing, where I write down the worried or critical thoughts I have about while I’m doing it: from information I need to check to issues around diverse representation. Then I know I can go back to those concerns during the editing process, but can park them and keep writing for now.

When I’ve written something and it has that feeling of potentially being too raw, or too vulnerable, to put out there at present, I leave it and return to it later: a month, a year, whatever.

I also have a sense of who my crew are for reading things that I’ve written which I’m not sure about sharing. If you know that the future version of yourself, plus several friends, will be reading the writing and feeding back about it before it sees the light of day, that can also help you to feel more free to write now.

Over time you can get a feel for what is just the right amount of vulnerable and what is over the line. Like if the exposure scale goes from 0-10 perhaps 5-6 is that sweet spot for things that are real and vulnerable in ways that stretch you a useful amount, and will likely connect with other people. But over a 7 is into the too-vulnerable zone and worth leaving till it feels less live. I’ve adapted this from an idea I got from Love Uncommon, that when our feelings are 0-7 the thing to do is to stay with them, but over 7 has tipped us into trauma/overwhelm and the thing to do there is to get back to a sense of being safe-enough before we try to stay with the feelings.

What if…

Here’s a few things people often worry about when writing about vulnerable stuff, plus my thoughts on them:

What if…people hate it?

I figure for everything I write there’s going to be a few folks who’ll really love it – the ones for whom it hits just the right point on the right day. Now that I have quite a lot of people who regularly engage with my stuff, there’ll probably be quite a few others who like it, which is great. Then there will be the vast, vast, vast majority of the world who have no idea who I am, no wish to read my stuff, and would feel pretty meh about it if they ever did. Then there’ll be a few people who – if they did read it – would totally hate it, either because they hate me – or people like me – or because it’s the opposite of what they think, or because they’re just having a bad day – or whatever.

In my case I’m generally writing for the people who find my stuff interesting, useful, or entertaining. Nobody else has to read it. If they do, and they don’t like it then that’s okay, they don’t have to read my stuff again.

What if…people are mean about me?

I think that people imagine that this will happen a lot if they put stuff out there, but it’s actually pretty rare. I write on some fairly controversial topics and I’ve very rarely have someone attack me or criticise my writing. It has happened, but to be honest it’s usually been something out of left field that I could never have predicted. I wouldn’t have avoided the experience by deciding not to write about the vulnerable stuff.

It’s definitely worth having some plans in place – if you write publicly – about what you’ll do if you do find yourself being criticised or attacked in a big way. Is there somebody who can take over your inbox and social media during the time it’s going on? Could you get away and do self-care till it’s died down a bit? Is there a holding message you can prepare in advance to put out while you take your time responding – if a response is required? Can you think advance of some kinds of filters to decide which kinds of critical feedback you’d like to take seriously and which you wouldn’t (around who gives it, in what form, what kind of issue it raises, etc.)?

What if…I change my mind later?

People worry that once you’ve written something it’s somehow set in stone and you could be judged for it FOREVER. I think it would be great if we could make a habit of returning to things we’ve written in the past and say how our views have shifted, or what we know now that we didn’t know then. We’re all in an ongoing process, and it’s not fair to judge a person now by who they were or what they knew 5, 10 or 20 years ago. Also culture is moving on and this makes it more possible to do better on many issues today than we might’ve done in the past. We could reflect on this process of change in our writing in useful ways – being accountable for the impact of our work – instead of being defensive and insisting that every word we’ve ever written was perfect.

What if…it’s vulnerable for other people I’m writing about?

This is where consent comes in (I said writing was like sex in more ways than one). If you’re writing about other people then it’s not okay to put something out there that could leave them vulnerable without their consent. There are several options here:

Only write your story, not those of other people who might struggle to read themselves depicted, or to have themselves read about by others. Having had the experience of being reported about in the press twice without my consent I know very well how utterly traumatic, confusing, and powerless this experience can feel. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.Keep things general rather than specific.Anonymise people (like I did when mentioning my clients earlier).Have consent conversations with people you would like to write about. Remember to acknowledge the power you have in the situation and any pressure they might feel under to agree to it: Ideally give them several options rather than just ‘go ahead’ or ‘don’t do it’. Take anything other than a definite ‘yes’ as a ‘no’. Remind them it’s fine to change their mind at any time (ongoing consent).Write collaboratively with the other people concerned so that you all have control over it together – this could be a useful process anyway.Write it as fiction rather than non-fiction, changing all identifying features, combining people together, or completely making up characters but keeping features of the experience true to life. This is what a lot of therapists do when they want to write about client work without breaking confidentiality. It’s what Alex and I do when we want to write a bunch of diverse experiences around an issue in our collaborative books.

There are complexities around all this of course when it comes to memoir writing particularly: what constitutes writing about somebody else versus telling your story? Again it can be useful to give yourself complete freedom to write what comes in the first draft, and then decide which strategies – or combinations of strategies – you’ll use to keep it ethical when you’re editing.

What if…I get something wrong?

You can go gradual. It’s not a binary of keeping something to yourself or putting it out there for all to see. You can have trusted friends read it first to give you a sense if it’s something worth sharing more widely. You can have sensitivity readers who you offer something to in return for reading it with an eye to particular aspects you want to be sure you’ve got right (e.g. axes of oppression you’re not personally familiar with but have written about, or science or history parts). If you have a publisher then you’ll have at least one editor who will read it before it goes out there. If it’s a blog then you can always share it only with a certain group of people, or put it out publicly but only share it with your social media friends or followers initially. And if you do get something wrong you can acknowledge that and change it immediately if it’s online, or in a later edition if it’s in print.

Writing vulnerable

Why would we write vulnerable stuff given all of these fears and potential pitfalls? I think that it does something very important for us personally, and for others reading our work.

Personally there is what Patrick Califia calls an antidote to shame in writing vulnerable stuff. This is often the stuff that we fear – deep down – might not be okay about us. Writing it and putting it out there is a way of saying ‘this is me, with all my inevitable frailties and failings and flaws, and I’m still okay.’ Under capitalism it could also be seen as a political act to challenge the success/failure and good/bad person binaries by speaking openly about our struggles, our mistakes, and our messes.

Related to this, writing vulnerable goes against the current pressure to curate and present a perfect image on social media and beyond (which brings with it a horror of being revealed as imperfect, which we inevitably are).

For me it’s always been about resisting the common depiction of the ‘self-help author’ or ‘expert’ who has it all together and doesn’t struggle in the way that ‘regular people’ do. Fuck that noise quite frankly. We hardly need another point of comparison to judge ourselves against and find ourselves wanting in the current climate. If we only put out our successes and triumphs and never our struggles and tragedies we’re feeding that culture of comparison. So we’d better get vulnerable.

Or we can sidestep the whole thing entirely as I do on Instagram and only share images of lovely nature/animals and food I’ve cooked (yes I am quite a good cook, but I’m rubbish at loads of other things I promise).

The post Showing Your Working: On Writing Vulnerable appeared first on Rewriting The Rules.

August 15, 2019

Remembering Audrey: Another memorial

Tonight is the full moon so another regret ritual for me. The more I do them the more each one seems to find the right shape for that particular time. Last time a celebration of my first day self-employed: A regretting of the heavy self-criticism that marked my time as an academic, a reflection on the impact it had on myself and others, a resolution to treat myself differently now that I’m my own boss.

This time a plan took shape as I took a train past the Long Man of Wilmington last weekend. That place reminds me of my Gran – Audrey. It reminds me of the stories she used to tell of wandering the downs above Eastbourne. Last time I was there I felt strongly connected to her.

When I wrote a memorial for my other Grandmother, Leslie, I promised I would do one for Audrey too – having not had the chance to do so when she died in my teens. It’s a more complicated story to tell. But I decided to do my regret ritual today around her, and to write this story as I sit here, now, above the Long Man.

[image error]Image of one of the views from the hill I walked to

Remembering Audrey

Some of my best childhood memories involve being on a hill much like this with Audrey. She moved all the way from Sussex to Yorkshire to be close to me and my Dad – her son. She lived with my Granddad in a bungalow near the Keighley moor and I visited her there on the weekends. I thought of her as old then, but I guess she wasn’t all that much older than I am now.

Friday nights she would make me my favourite meal: roast chicken and homemade chips. We listened to singles on her record player and danced to Shakin’ Stevens. We read her grisly true crime books and gave ourselves the shivers.

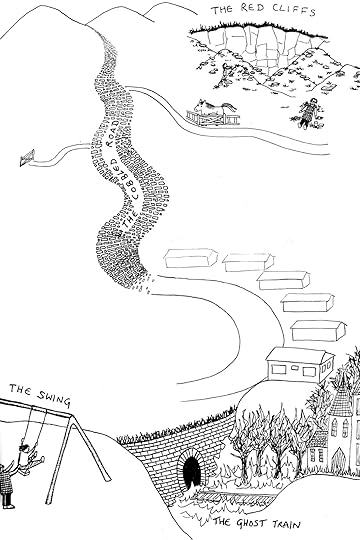

Saturdays she packed a lunch and took me up the cobbled hill above the cul de sac where she lived and onto the moor. The hill seemed like a massive climb then but I guess it wouldn’t feel so far now. We always made for our spot – the red cliffs: a magic place where heather covered hillocks hid a disused quarry. Gran sat at the bottom while I clambered up over the heather and rocks, adventuring. I remember the feeling: free and wild and at the same time safe and loved, returning to Gran when I was done. We sat there watching the Worth Valley steam trains make their way along the valley far beneath us, eating chicken sandwiches and the little purple bilberries growing around us. She’d tell me how she used to climb like me – up on the Sussex downs. She said those were her happiest times too.

Cartoon image of my Gran’s place, the red cliffs, the playground we used to go to, and the disused railway tunnel next to her house where she told me a ghost train still passed during the night

Cartoon image of my Gran’s place, the red cliffs, the playground we used to go to, and the disused railway tunnel next to her house where she told me a ghost train still passed during the nightLater, after she moved to Bradford, our days together became adventures where we’d get on the first bus that came along, sit upstairs in the best spot (monarch of the bus), and go wherever it took us – Keighley and Haworth generally being the only options but I didn’t know that at the time. I remember her telling me stories about this family of kids she’d made up, and feeding me maltesers. She’d push me on the swings in the park, take me round the little shops, and get us fish and chips to eat at the bus stop before we headed home to bath and bed.

Love and Loss of Love

When I think of those times together, love is the word for it. The way Audrey delighted in me – my excitement at all that we saw and did and talked about – combined with the safety and kindness I felt from her, cuddled up in the evening watching TV after all the adventuring.

But it’s a complex story because Audrey also taught me what it is to lose love. I remember it vividly. I guess it was around the time I started adolescence. I was being bullied at school: learning that I wasn’t okay in all kinds of ways, that I’d have to hide my innocence and difference and enthusiasms if I wanted to get on. Gran had moved into sheltered housing. I think she probably struggled as much with the other people there as I did with the kids at school but I didn’t see that at the time.

I remember one evening I made a critical comment about someone on the TV who annoyed me. She became furious, saying I didn’t know what that woman had been through, what a hard life she’d had. In retrospect I think it must’ve been someone she identified with. It struck some painful chord from her own life. I remember the disappointment, disapproval, even disgust on her face as she looked at me. I linked it to the way she’d looked when I told her I’d started my period. She called that the curse.

This felt like a curse. Suddenly everything about me was wrong. And the things I was doing to survive this situation I was in made me someone my Gran couldn’t love any more. It happened a couple more times: her getting enraged like that, seemingly out of nowhere. It scared me and it confused me. I didn’t tell anyone about Gran’s anger just as I never told them about the school bullying, or my fears that there was something wrong with my body.

Gran and I became distant. She transferred her affection to my sister. Before I was out of my teens, she died. I felt guilty for betraying her, for seeing her less and less, for rarely visiting her in hospital. Her funeral was horrible: fake music and this person talking who didn’t even seem to know her.

Stories and Patterns

You could tell a lot of stories through what happened between me and my Gran. I later found out that this was her pattern with family and friends – to love people fiercely and fully – looking on them as golden ones – and then eventually flipping and feeling betrayed by them – hating them and often casting them out of her life, or at least her heart.

You could say it was terrible that she did that to me – a little kid. Just at the time when I needed her love to be a constant to demonstrate to me that I wasn’t all the bad things I was being told I was, instead she acted in a way which confirmed it. And she was the grown up. She should’ve known better; done better.

Or perhaps she saw what was happening to me: saw the delightful, playful kid she’d loved disappearing and this hard, unhappy, critical person taking their place; clumsily trying to be what other people wanted them to be and losing themself in the process. Maybe she couldn’t bear that: losing me that way. Maybe it was also what had happened to her once upon a time.

Or perhaps this is just what it’s like for everyone going from childhood to adolescence. Maybe I should just get over it.

[image error]Butterfly I saw on the walk

But the point is I never really could get over it. My whole life I’ve longed to feel again that kind of love I felt from Gran. It’s like she passed her pattern onto me because whenever I seemed to find that kind of love I would love fiercely and fully in return, but if the person ever looked at me the way Gran did those times – with disappointment, disapproval, or even disgust – I’d find it totally unbearable. I would do anything to avoid that happening: becoming hypervigilant, trying to be whatever they would find loveable, avoiding saying or doing anything they might not like.

That kind of pressure often meant that when I couldn’t keep it up – all that work – I would become really hard to handle: desperate, flailing, unreachable, inconsolable, self-loathing. And of course that made it even more likely I’d get that look. As it happened more and more I wouldn’t be able to bear it so eventually I’d leave. Often I’d wait until another person had come along who might give me the kind of love I craved. Somehow being without it at all felt too hard.

Of course there’s more to my patterns than this: other stories that I have told – and will tell – in other places. There are stories about the cultural messages around love we all receive, stories about other early relationships I had and their impact, stories about capitalism and what that does to us, stories about how we all struggle to be with each other in our complexity – not grasp for the ‘good’ and hurl away the ‘bad’. There are stories about the patterns of the other people involved – which are not mine to tell – but which were part of the picture too, of course.

And there are relationships where I’ve resisted this pattern: found other ways to be, or containers for the relationship which have enabled it survive moments where I felt like my old horror was being lived out again.

But this feels like a pivotal story for me. And it’s not over yet: the pattern still happens.

[image error]First part of my walk – trees meeting overhead

Memorial

So today I decided to come here, where I imagine Gran used to come when she was a kid, maybe before all of her patterns got put in place: the ones she somehow passed on to me.

Despite being mostly veggie these days I allowed myself the happiest chicken I could find. I ate it with homemade chips last night and made sandwiches this morning. I got on the first bus that came along near my house: the Coaster that runs from Brighton to Eastbourne. I got off at Friston and walked through the forest. I saw a fawn with an adult deer in the woods: they seemed impossibly fragile to me. Lots of fragility on the walk.

[image error]Image of a lamb from my walk who was both fragile and robust – didn’t seem to fancy moving anyway

I came to this spot by the Long Man, eating blackberries instead of bilberries along the way. And now I’m sitting to write this on my phone and popping maltesers. Later I’ll have my sandwiches looking down over Eastbourne, watching the trains make their way along the valley beneath me.

It strikes me that through my life I’ve taken the journey Gran took in the opposite direction: from Yorkshire to Sussex. I’ve moved down the country till I’m where she began – walking her chalk hills instead of my moors. I have to stop my progress south now. I’ve finally met the sea.

I’ve carried these patterns with me all this way, leaping from love to love with no break in the chain, trying to get back what I once had and leaving every time it looked like it was going the same way as before. I’ve tried everything to do it differently. I’ve reflected and written about it, I’ve warned people about it, I’ve shown them every part of me. But still I gave too much of myself away in an attempt to get that love and had to leave to get myself back. Still I couldn’t seem to bear it when the love dropped into that other thing – the disappointment, disapproval, disgust.

So now I’m trying the one thing I haven’t tried yet: not doing it. I’m staying with those old, old feelings of loneliness and longing for love, of yearning for somebody else to prove that I’m okay, and fearing that I’m really not. I’m trying not to push the feelings down, not to blame anyone else for them, and not to look to anybody else to make them go away. It’s really fucking hard but I think it’s the only way to change these patterns, and the pain and loss they cause to others and to me.

I’m doing rituals like this to try to find the love and kindness and safe-enough feeling that I long for within myself. I’m reaching out to all of my people, being vulnerable, and letting them into this so that I won’t be tempted to put it on one person any more. And hopefully those people will feel able to let me know if they see that happening again.

Today I do this ritual of regret for my Gran and for myself. I’m so grateful to Audrey for showing me what love can be, and I’m grateful to myself for managing to do this now. I also forgive Audrey for passing on this pattern – this curse – which has lost me so much love, home, and family along the way. Goodness knows what she went through to make her that way, or what the people went through who did that to her, or the ones who did that to them. As I forgive her I try to also forgive myself and to forgive all of us who are caught up in our own patterns, passed down through the generations, hurting each other and hurting ourselves. May we all find some kindness in this sorrow, in this regret.

[image error]Image of a gate from my walk with the word ‘thankyou’ written on it

The post Remembering Audrey: Another memorial appeared first on Rewriting The Rules.

August 12, 2019

Straight people going to gay events and venues

Recently Grace Walsh interviewed me for this great piece about straight people going to gay bars. You can read my full thoughts here on straight people going to queer venues and events like Pride here…

How can straight, cis people be respectful in LGBTQ+ spaces?

This is a topic that comes up a lot around Pride season. Some of the bigger prides becomes so inundated with straight, cis people who want to enjoy the parade and festivities that it stops feeling like a proud – or safe enough – space for the LGBTQ+ people it was designed for. This also often elevates the prices making them increasingly inaccessible for more marginalised LGBTQ+ people.

Similarly LGBTQ+ friendly areas like Brighton, London Soho, or Canal Street in Manchester have become go-to places for stag-dos, hen-dos, and other straight, cis celebrations, perhaps seen as appropriate places for people to experience one final ‘walk on the wild side’ before tying the knot.

Why are queer events and spaces important?

It’s worth remembering the roots of queer venues and celebrations like Pride. Back in the late 1960s in the US gay, queer, and trans folks had to fight not to be ejected from venues like the Compton Cafeteria in San Francisco, or raided by the police in pubs like the Stonewall Inn in New York. The first Pride marches had their foundations in the riots that took place to protect these queer spaces, often led by those who were also working class, sex workers, and/or people of colour.

It’s easy to imagine that things are far better now than then, but rates of homophobic, biphobic, and transphobic hate crimes and discrimination have all gone up markedly since the Brexit vote, and we’re in the midst of a huge moral panic against trans people, as well as ongoing battles around how sex, gender and sexuality are taught in schools. Globally there’s still the need for a trans day of remembrance every year to mourn the frightening numbers of trans people – mostly trans women of colour – who are murdered annually. Related to all of this, mental health and suicide rates among – particularly young – LGBTQ+ people remains a big concern.

In many places LGBTQ+ people still don’t feel safe enough to express themselves – or their relationships – openly. Even where they do the backdrop is of heteronormativity: the assumption that people are straight and cis unless they ‘come out’ otherwise, and that being LGBTQ+ means being different from the norm in ways that we need to explain and justify in some way, with pressure to prove that we’re ‘normal’ in every other respect. Many LGBTQ+ people have strained or non-existent relationships with previous friends and family, so building their own friendships, support networks, and social spaces is important.

LGBTQ+ people often become used to having to come out repeatedly, to being asked intrusive questions about their bodies and sex lives, and to being treated as an object for people (the weird one in the office, or the gay best friend, for example). They have to be part of everyday workplace and family conversations which assume that everybody wants – for example – to find a partner, get married, and have (and gender) kids, and that those things require celebrating in ways that transitioning, finding a community, or coming out, do not. It’s understandable that they might want some spaces where they don’t have to worry about that stuff or self-monitor constantly: where they can assume that everyone will ‘get it’, relax, and breathe easy.

Think about your motivations

So if you are straight and cis and thinking of attending an LGBTQ+ space or event, think about your motivations. Generally speaking it’s probably a bad idea if you’re looking for the following:

To share your opinions about LGBTQ+ people or get into arguments or debatesTo see something strange, exotic, or titillatingTo flirt or get off with somebody LGBTQ+ because you’re curious or want to have a story to tell – this involves treating people as objects for your pleasure, not full human beingsTo have a laugh by doing something a bit crazy and out-thereTo exploit or appropriate the coolness of LGBTQ+ culture in some way

These are better reasons:

You want to support your LGBTQ+ friends who are keen for you to go alongIt’s an event or space that’s particularly looking for allies to support it – and the people goingYou’re genuinely questioning whether you might be LGBTQ+ yourselfIt’s an educative space and you want to learn something

What not to do

Go with your straight, cis partner and get off together very publicly in the space – remember that everyday spaces are safe for you to do that in a way they aren’t for the rest of the people thereGo with your straight, cis mates and take up a lot of room in the venue with your bodies or your noise – many people will feel less safe if you’re doing thatGo to places with a maximum capacity which are already pretty full – better to let LGBTQ+ people be the people who get to use the spaceAsk intrusive questions of anybody there or touch anybody without consent Get super drunk or high so others have to look after you

What to do

Check beforehand whether you will be welcome there – with staff or others attendingBe friendly and treat people as full human beings, not just their sexuality or genderDo your homework if it’s an unfamiliar community for you – there are plenty of vids out there about things LGBTQ+ people are sick of hearing, or what not to ask them, as well as easy 101 introductions to languageBe kind, consensual and unobtrusive – it’s not your space and you’re privileged to be welcomed here

And LGBTQ+ people need to remember…

Not everybody who appears to be straight and cis in an LGBTQ+ space actually will be. There are plenty of people who, for whatever reason, are not safe to be out as LGBTQ+, or don’t identify with that terminology, but are still attracted to the same gender or more than one gender, or living in a different gender to the one they were assigned at birth. There are also lots of people who don’t look like the common image of an LGBTQ+ person (which is so often white, young, slim, non-disabled, and middle class). There are many who aren’t into the LGBTQ+ ‘scene’ but are still LGBTQ+. This is often an issue particularly for bi people. Remember that just because somebody is with a different gender partner, or hooking up in that way, doesn’t mean they are straight. And even if they are straight, they may not be cis. They may be there because they are trans. Also femme women can feel very invisible in LGBTQ+ spaces.

Many people may access LGBTQ+ spaces because they’re questioning their gender and/or sexuality and that’s a really good reason. Insisting that they make definite decisions, identify or express themselves in certain ways is not okay. Also remember the + on LGBTQ+. There are good reasons to consider including asexual, intersex, kinky, and/or non-monogamous people, as well as sex workers, under the broad umbrella of people who are excluded from heteronormativity and discriminated against by virtue of their gender and/or sexuality. There are legitimate conversations to be had about who should and shouldn’t be included, and in what contexts – for example, not all intersex folk want to be added to the LGBTQ+ acronym and it’s very important to respect that – but generally it’s worth being as careful when making assumptions about somebody who doesn’t appear LGBTQ+ as we’d want people to be when coming into contact with somebody who does.

The post Straight people going to gay events and venues appeared first on Rewriting The Rules.

August 1, 2019

Queer loneliness and friendship

I recently did an interview for this great piece on queer loneliness, and how to find LGBTQ+ friends. It was a nice one for me because I did my PhD on loneliness many years back. It felt good to return to the topic now that I’m leaving academia. You can read the full interview below…

Why is loneliness is so prevalent in LGBTQ+ communities?

One initial reason is that LGBTQ+ people are less likely that straight and cisgender people to have the kind of ‘built in’ relationships that come from the family you grew up in, school or college friends, or even current colleagues. Of course these days many do, but still many become estranged or distant from old family and friends who struggle with their gender and sexuality. Others just don’t feel really comfortable hanging out with people whose assumptions and conversations are always focused around a heteronormative life (e.g. fancying the ‘opposite sex’, hanging out with the ‘same sex’, a social life that is linked to stereotypes of masculinity or femininity in particular ways, marrying, having children, etc.) So LGBTQ+ people are more likely to have to forge friendships in later life, which is often more challenging.