Gabriel Bergmoser's Blog, page 8

October 26, 2019

The old school

I’ve been called many things, but ‘Writer in Residence’ is definitely a new one. I don’t even 100% know what it means, but I do know that last week it was my job, as I was invited to return to Caulfield Grammar School to run a bunch of writing workshops with students across every year level.

I’ve been called many things, but ‘Writer in Residence’ is definitely a new one. I don’t even 100% know what it means, but I do know that last week it was my job, as I was invited to return to Caulfield Grammar School to run a bunch of writing workshops with students across every year level.It was an exciting and flattering offer that came about due to a chance run-in with Michael Knuppel, my old literature teacher and a staunch early supporter of my writing. After telling Michael about the stuff I’ve been up to of late he suggested a return to Caulfield on the other side of the classroom divide and I was more than happy to oblige. But, as seems to be the theme lately, things turned very busy and returning to my old school was immediately preceded by a week in Sydney working in writers rooms with only a single day off in between, so by the time I set foot on campus again I’d be lying if I said the residency was something I’d been thinking a lot about.

At first, being back was pleasant but a little weird. Walking into rooms I hadn’t seen in ten years prompted a bit of a deluge of long buried memories – places where fights, wide ranging conversations and romantic interludes had occurred over the course of the three years I spent there. But alongside this were the many ways in which the school had changed. It made for an oddly mismatched experience, one of mingled nostalgia and unfamiliarity that left me feeling at a bit of a remove from everything, like a half-forgotten ghost drifting through the halls, neither a total stranger nor completely belonging.

This feeling grew and came into focus over the following days. Understand; Caulfield was a huge part of my life. Leaving my hometown to board in the city precipitated everything that happened next. Boarding school was a massive change in my teenage life, a bittersweet uprooting from the home and friends I knew, undertaken in order to chase something ostensibly better. And while the ride was always bumpy, the school did exactly what it was supposed to, leading to lifelong friendships and opportunities that created the path I’ve been on ever since. And then there are the ideas that came from my time there. Without Caulfield there’s no Boone Shepard or Windmills. Without Caulfield I’m not convinced I would be the same person.

Boarding means that school becomes your life in a way it doesn’t for others, which means that leaving is more than just finishing your education; it’s leaving home all over again but this time stepping out into the world without the possibility of returning. Safety vanishes, your friends aren’t constantly around you anymore and so in a weird way I think my memories of Caulfield Grammar eventually become a sort of yearned for halcyon time precisely because there was never any chance of a homecoming or easier transition. Once I was out, I was out. Until, of course, last week.

But ten years is a long time and a school, even a boarding school, sees that mass exodus of part of the ecosystem every year. My goodbye was ten cycles ago, so any sense of re-establishing some past connection was always going to be a little one sided. That’s not to say that between classes I didn’t indulge in a little nostalgia wallowing. I wandered through the boarding house, went down into the drama studio, the walk to which remains lined with photos from plays I either saw or was in. I sat outside the school and did a bit of work on Windmills for the first time in over a year, almost in the same spot where I first started the book a decade ago. Sometimes, in those places, echoes of the past seemed to creep back; a familiar smell, a sight or detail I thought I’d forgotten, memories and names that I haven’t had occasion to think about in years prompted back by an unexpected association. A sense of disconnect and unfamiliarity persisted, but not all the time. Sometimes the past shone through.

But even a quite literal homecoming like this one ends up being a bit stunted. My time at Caulfield and the particular feelings I associate with it were made up of the irreducibly complex tapestry of so many impossible to recapture factors. The friends I had. The music I listened to. The teachers, most of whom are long gone. And above all, the person I was then; petulant, childish and so gloriously stupid about so many things.

At that school I felt more keenly than I have in years the presence of the dumb kid I used to be. With that comes sadness; that I’m not that openly emotional anymore, that the earth-shattering thrill of seeing your crush smiling at you or getting the lead role in a school play no longer has the immense power it once did, that I’m can’t as easily just be joyful. But the sadness sits hand in hand with pride. That I’m learning to move past the tunnel-vision selfishness, the back-stabbing cowardice, bad temper and arrogance that characterised my teenage self, traits I’ve figured out how to recognise and eschew wherever I can because they’re no longer indicative of the person I want to be.

I think I spent a lot of my early writing career exploring nostalgia and why it’s not ultimately a good thing (Reunion, Hometown, One Year Ago) largely because that was a lesson I was struggling to learn myself. A few years on, my perspective has changed a little. I don’t think nostalgia is inherently a good thing, but I also think that it’s healthy to remember and engage with where you came from, if only to remind yourself of how far you’ve come.

Published on October 26, 2019 18:43

September 19, 2019

A retraction

A few years ago I was listening to a radio interview with an author who said ‘I write because it’s cheaper than therapy’. At the time I laughed knowingly without giving any thought to what the statement actually meant. My feeling then was it spoke to the idea that we’re all sexy tormented artists grappling with the weight of the world. The truth is way more mundane than that. My personal theory is that writers write to try and make sense of things. Whether it’s a novel, a short story, a review or an article, just about all writing is a response to something experienced or witnessed, refracting reality through a worldview, narrative and sensibility that makes it all just a little more palatable.

A few years ago I was listening to a radio interview with an author who said ‘I write because it’s cheaper than therapy’. At the time I laughed knowingly without giving any thought to what the statement actually meant. My feeling then was it spoke to the idea that we’re all sexy tormented artists grappling with the weight of the world. The truth is way more mundane than that. My personal theory is that writers write to try and make sense of things. Whether it’s a novel, a short story, a review or an article, just about all writing is a response to something experienced or witnessed, refracting reality through a worldview, narrative and sensibility that makes it all just a little more palatable.To explore this a little further, I’m going to talk about Community.

I first got into the show in around 2012, because it was a cult favourite that a lot of my friends were watching. I followed suit and predictably loved the tribute/concept episodes and the dark humour, but there was plenty I didn’t appreciate. Like the occasional episodes that went dark and sad instead of funny. Or the fact that the show spoke endlessly about the importance of the central group’s connection without, for my money, actually doing the work to build that connection. I found the more conceptual third season a pretentious mess of half-baked ideas and I started to get frustrated at the ongoing media narrative suggesting Community was an underappreciated modern classic. So much so that I wrote a lengthy blog post about the fact. I think it might have been like, the second thing I posted here.

Reading that post again makes one thing abundantly clear; I really, really did not get Community. And I don’t think I could have, at the time. To explain what’s changed, let’s get personal.

I’ve spoken before about 2015 as a bit of a low point for me. There are several reasons for this, but I think the key one is that it was the first year where I started to realise I wasn’t the person I wanted to be. I’ve always gone through bouts of insecurity and uncertainty, but 2015 was something else because almost overnight my life changed in intangible ways that it took me a long time to wrap my head around. For a couple of years prior, I’d lived a carefree life of casual work, partying and writing. I had good friends all around me, a fun party house that was always full of life and collaborators helping me get my work on stage. Then things changed. I moved into a cramped, dingy apartment that had a constant sense of wrongness about it (I found out later somebody had been murdered there), the kind of place people didn’t really want to visit. My housemates weren’t around often, understandably preferring to spend time with their respective girlfriends. I started working a dull job in a distant, dodgy suburb that was a two hour commute each way, leaving me barely any time for anything other than work.

The newfound distance from everyone who had previously been such major figures in my life just underlined a growing sense of worthless isolation. Somewhere along the line I had taken a wrong turn and couldn’t seem to find my way back to the previously promising road I had been on. I was stuck somewhere between adolescent and adult, living a sad facsimile of my previous life all the while preoccupied by a sense that I needed to grow up but with no idea of how. I had reached the end of my Masters of Screenwriting with no clear path forward and started to realise that my hard-drinking lifestyle was no longer the norm. Excess is a lot less fun when you’re the only one indulging in it. In fact, up against the seemingly sudden maturation of those around you, your own behaviour can be cast in a new light that shakes your sense of self to the core and leaves you wondering what’s wrong with you.

I lost confidence in my writing. I lost confidence in myself. And through all this, during my lowest ebb, the sixth season of Community was coming out.

Now, the sixth season is nobody’s favourite. Half the main cast have been replaced, the sharpness of the writing isn’t the same and there’s a sense of sadness to the whole thing that makes it feel dreary compared to the crackling wit of earlier years (ignoring, obviously, the Dan Harmon-less fourth one). And yet the more I watched the more I found myself developing a new perspective on Community and, in particular, on protagonist Jeff Winger.

I can’t imagine anyone is reading this without at least a basic knowledge of Community, but for context the series starts with Jeff losing his job as a lawyer when it is discovered that he never went to law school. In order to be reinstated as quickly and easily as possible he enrols at the highly dodgy Greendale Community College, to him a humiliating step down. He quickly gets drawn into the lives of a gang of misfits with whom he forms a study group and welcome to the plot of our sitcom.

What is unique about Community – apart from everything – is Jeff’s development. Naturally, his arc early on is the growth of genuine caring for his newfound community (geddit?). But as the series continues something kind of interesting happens. The show starts to call him to task, even outright suggesting in approximate series midpoint Remedial Chaos Theory that Jeff is holding the entire study group back from actual development. This subtext becomes text in season six when, necessitated by the many departures of main cast members, the show starts to centre on Jeff’s growing anxiety that he will be the last one left at Greendale – a fate his season one self would have seen as worse than death. The final season mines genuine (but still funny) pathos from his growing desperation to hold his found family together as the last remaining younger members start to look beyond college to what the next stage of their lives might look like, right as Jeff starts to realise that the next stage of his life is this.

In retrospect, it’s easy to see why 2015 me might have found the sixth season of Community so affecting. But honestly, at the time I just assumed that its new dour sensibilities suited my mood and didn’t examine the correlation any further. Understand, the moments were rare in which I could admit even to myself that my real anxiety was that I had been left behind by everyone I cared about.

Of course, insofar as stories in real life have endings my 2015 had a happy one – I got out of the murder apartment, won a screenwriting award that changed my life, reconnected with my friends and entered a period of renewed artistic passion that included a handful of genuine successes. But I still found myself thinking about Community’s ending, even divorced from the mindset that drew me to it.

As somebody who has always been obsessed with stories, I used to be troubled by the gap between the appealingly flawed but ultimately great lives and personalities of characters on screen and my own. I think I lived in fiction to such a degree that the messiness and ugly sides of my own nature became genuinely challenging to me, a kind of signifier that I was wrong somehow. Maybe that’s partly the reason that Mad Men always spoke to me so much; after all, the characters on that show are largely trying to come to terms with the fact that the perfect life they propagate is so vastly different to their realities.

In Community, every character is dealing with that divide. Jeff just takes the longest to realise it. Every single member of the study group has either let themselves down in some way, is not capable of dealing with the real world or both. The fact that Jeff and Britta are the last of the original study group remaining by the end might have been due to the increasingly difficult schedules of core cast members, but it also makes perfect sense that the two most initially self-assured characters were the two most deluded about who they really were.

The sadness of Community, then, was not unique to season six. On rewatch it slowly became clear to me that it had been there all along, that the through-line to the wacky adventures of the study group was a fundamental sense of failure that they all struggled to contend with. The reason they clung so desperately to each other (in increasingly pathological ways) was because they didn’t think anyone else would accept them. Other sitcoms might poke fun at their characters’ co-dependency, but would never ultimately explore the dark why of the fact. Community did, and that’s one of the reasons it was so bold and subversive. For all the kooky sitcom trappings, it reflected real life in a distinctly ugly way without losing sight of the bruised humanity at the heart of its characters.

This is why Community is, for all its flaws, so much better than Scrubs or How I Met Your Mother or any of the other sitcoms I spent my teens and twenties watching. It doesn’t stop at what’s easy or digestible. It pushes into the gaping chasm that exists in all of us between who we are and who we think we should be, and in that place finds something hopeful.

The best writing is a kind of therapy, but not just for the writer. The best writing reaches through the screen or page and tells the audience ‘I’ve been there too, and you’ll be okay’. And when you really need to hear that, there’s little as powerful.

Published on September 19, 2019 02:45

September 14, 2019

Ten years burning down the road

As of September 2019, it’s been ten years since I discovered Bruce Springsteen.

As of September 2019, it’s been ten years since I discovered Bruce Springsteen.I’ve spoken before about my longstanding and passionate love for Jonathan Tropper’s novel The Book of Joe , which I read in high school and immediately connected to. The Book of Joe tells the story of a successful author who became famous for writing an unflattering book based on his hometown, who is then forced to return to said town after his estranged father has a stroke. It’s not a perfect novel – it’s overwritten with a few unnecessary narrative diversions – but it’s so deeply felt and nakedly emotional that, as a small-town kid with aspirations of a writing career, it was close to revelatory for my sixteen year old self.

It also is packed full of Springsteen references. The first time I read it, it was with a vague sense of ‘huh, maybe I should check that guy’s music out’. When I read it again a year later in 2009 I realised I would have to look up the songs to fully understand what the book was talking about. I started with Backstreets, a track that is a very particular motif in The Book of Joe. It was a pretty immediate sell; Backstreets is a passionate, mournful roar of a song – I remember at the time thinking it sounded like a voice on fire. I had to hear more.

At the time, I had been asked by a friend to take part in a play of hers out in Warburton. Given that I was about a month out from my Year Twelve exams the worst possible thing I could have done was say yes. I said yes. And without getting bogged down in specifics, it was one of the best decisions I ever made, something that led to lifelong friendships, my current relationship, my first plays being performed and piles of valuable life lessons. But more immediately, it led to one of those dreamlike phases of passionate, hedonistic perfection that you only really get when you’re a teenager; nights of drinking around campfires, writing songs together and swearing lifelong devotion to each other. It was, at the time, like I was living two different lives; during the week I fretted about exams and rigidly followed the rules of my old-fashioned private school, but on weekends I entered a whole other world, one where normal rules didn’t apply and everything might as well have been taken from a sweetly nostalgic coming of age film, except it was real and better than any of those films could ever be.

I remember one morning waking up on a couch outside, looking out over the misty hills and the trees. I sat there alone listening to Thunder Road and in that strange and magical way that music can sometimes achieve, my very particular emotional state was reflected back at me. From there the Born to Run album became the soundtrack to my life; all those songs of passion and escape, of getting out of your town full of losers, of locking up the house and stepping out into the night to see what was waiting for you, of soft infested summers and girls you agonised over.

Did the songs make the time or did the time make me susceptible to the songs? It’s hard to say. But Born to Run will always be synonymous with a phase of my life that I’ll always hold dear. That alone would be enough for me to forever love Bruce Springsteen. Except Bruce has a habit of giving you far more than you could have hoped for or expected.

In Wrecking Ball Springsteen tells us that ‘hard times come and hard times go; just to come again.’ And while I appreciate that in the context of his songs such messages tend to refer to the economic difficulties of the working class, it’s also reflective of something I’ve learnt more and more is true; that no matter who you are, happiness never lasts but nor does the darkness and that’s the way it should be. You need the bad to appreciate the good, and both will come and go.

The idyllic time in my life that I’ll forever link with Born to Run ended, because of course it did. Secret romances and perceived betrayals left the friendships we swore would last forever in tatters and while reconciliations came it was never the same. In retrospect, the fact that the songs on Born to Run so perfectly reflected that time stands to reason, because Born to Run is very much about the end of innocence, about the last gasp of childhood idealism before the realities of the world set in. And for that reason, I still can’t finish a full listen of Born to Run without diving straight into Darkness on the Edge of Town, the starkly different follow up album that, for my money, serves as one of the most perfect sequels ever.

2010 was a very different year to its predecessor. I was broke and alone in the world, at a uni I hated without any of my former friends, working shitty jobs to make exorbitant rent and trying to wrap my head around the fact that all of my beautiful shining dreams about what early adulthood would be would not come true. It’s not that I had it especially hard, but no matter your circumstances the realisation that your life is not going the way you expected will never not be a challenge. Darkness, then, became the soundtrack to a different portion of my life. I would walk around the streets at night listening to Badlands or The Promised Land as a kind of defiant middle finger to a world that wasn’t giving me what I wanted. It was like Bruce was telling me to get back up despite the disappointments and the traps I seemed to be surrounded by; ‘you wake up in the night with a fear so real, you spend your life waiting for a moment that just don’t come; well don’t waste your time waiting.’ Later that year, when I finally hatched a plan to change my circumstances, to get into a job, university and house that I would be happy with, I clung to a different, far later Springsteen song. I played Working on a Dream over and over again as a kind of mantra. Every time my unpleasant circumstances threatened to get me down I whispered the chorus to myself; ‘I’m working on a dream.’ By the end of that year, I’d achieved what I set out to. I worked at Dracula’s (at the time a dream come true), I lived in a cool apartment in the middle of the city, and I had transferred to the best uni in the country. With Bruce as my guide I fought to change my circumstances and while in the grand scheme of things the victory was minor, it was real and it was mine.

In The Book of Joe, the main character semi-jokingly says ‘there’s a Springsteen song for every occasion’. Over the years I learned the truth of that, in times both good and bad. In 2012, after my first serious breakup, We Are Alive became the anthem of hope and comfort that kept my head above water. As I entered a new period of creative and personal fruitfulness in 2013, I listened to the celebratory exuberance of Thundercrack on repeat day after day with a big smile on my face and spirits lifted every time. When I finished my Masters in 2015 and found myself with no clear path forward, personally or professionally, the mournful tracks on Tunnel of Love were like a gentle reminder that I wasn’t the only one who felt that way. And while so many of those albums and songs will always be linked to particular times, places and people, none of them were ever just a reminder of something past. I came back to them again and again, seeing new layers on every visitation.

In 2016, as I entered a place in my life and career where I started to slowly shift out of the ‘aspiring’ category when it came to calling myself a writer, Springsteen’s autobiography became a kind of holy text for me, a beautifully written book that reminded me when I needed to hear it the most that while art and creative success are brilliant, they’re not everything. This sentiment led me to finally write a play about Bruce’s life, my own attempt at a kind of tribute to him, and a work I remain very proud of.

At a certain point my appreciation, love and respect grew to encompass the man as well as the music. Springsteen’s philosophies, his honesty, his decency and his never ending drive and passion to continue experimenting and taking risks while at a place in his career where he has nothing left to prove became a perpetual source of inspiration, the ideal of what an artist could, and perhaps should be.

Even as he nears seventy he keeps on giving. Next month two Springsteen films are hitting Australian screens. Western Stars, a sort of concert film/mood piece adaptation of his latest album, and Blinded By The Light, a movie that by all accounts captures exactly what it is to be seventeen and discovering Bruce Springsteen for the first time. In the trailer, we see the protagonist prowling the late-night streets, leaning against walls overcome with emotion as The Promised Land and Dancing in the Dark blare in his ears articulating all the things he struggles to say himself. Watching that hit me so hard because of the sheer specificity of that very familiar moment.

There are other musicians I love, other careers I’ve followed closely and other songs that have provided a way to express the inexpressible. But Bruce Springsteen, for a decade of my life now, has pulled off the same trick again and again, providing an ongoing collection of reminders that no matter how bad things might seem, you’re not alone. Joy, love, pain, regret, defiance and hope; Springsteen expresses them all with a power and honesty that is singular. Art, at its best, makes whatever loads we all might be carrying lighter; whether offering an escape or a necessary reflection, making everything just that little bit easier to digest and deal with.

Once I had a dream that I met Bruce. In fact I’m lying, I’ve had several of those dreams. But the one I’ll always remember is the one that rang the truest. I saw him, shook his hand, and said ‘thank you’. Then I left. Because after everything, what else could I ever say or do to convey how much his work has meant to me?

The past decade of my life, representing the slow construction of a career and the slower growth into an approximation of adulthood, has been a messy, bumpy, sometimes ugly time. I haven’t always been the person I wanted to be. I’ve hurt people and let them down. I’ve embarrassed myself and been a pathetic, childish failure; a mix of arrogance and insecurity that sometimes makes me marvel at the fact that anybody has stayed my friend for more than a day. But beside the darkness sits the light. The wonderful people I’ve shared the journey with, the times I’ve had that I’ll remember and love forever, and the hard-won successes that were all the sweeter because I know I earned them. But the consistent voice that guided me through all of it belongs to Bruce Springsteen. And I can say, without hyperbole or self-consciousness, that none of it would have been the same without him.

Thank you Boss. Here’s to the next ten.

Published on September 14, 2019 08:04

September 4, 2019

Sydney again

As you may or may not know, recently my TV concept Endgame was a finalist in the AACTA Elevate Pitch competition. This in and of itself is a big deal; the winner gets some development support and the prestige of the AACTA name on their project, but every finalist gets to pitch onstage in Sydney in front of an audience of industry people. So, first thing Saturday, producer/friend Dan Nixon and I were flown up to Sydney to basically try and sell the show.

As you may or may not know, recently my TV concept Endgame was a finalist in the AACTA Elevate Pitch competition. This in and of itself is a big deal; the winner gets some development support and the prestige of the AACTA name on their project, but every finalist gets to pitch onstage in Sydney in front of an audience of industry people. So, first thing Saturday, producer/friend Dan Nixon and I were flown up to Sydney to basically try and sell the show.I was not prepared. It’s been a busy time and to be honest, the Endgame pitch was at the back of my mind. I kept trying to make myself rehearse or even write out what I was going to say, but other things kept getting in the way and so I got on the plane Saturday morning with only the vaguest notion of what I was going to do.

The moment we arrived at the Factory Theatre reality started to set in and so Dan and I ran through our pitch again and again. We only had two minutes to convey what was special about the show, but pretty quickly we settled on a pitch that felt right, engaging. Not that that in any way assuaged nerves as the clock ticked down and two really great pitches preceded us.

We didn’t win, but given how deserving the pitch that did was, how clearly the creator understood her product and how perfectly she articulated her ideas, it was hard to be too upset about that. In the end I think we did well. We got laughs in the right places and plenty of people approached us afterwards to congratulate us on the pitch, give us their details and ask to know more about the project. It was thrilling enough just to be there and to see how much potential and marketability Endgame really has. For the project, it was a super energising experience and leaves me excited to see where it can go next.

Sunday was pleasantly lazy; Dan and I wandered around the city, had breakfast overlooking the sunny harbour, browsed bookshops and drank beer at the Rocks before Dan headed off for his flight home, leaving me alone and ready to take Sydney by storm. By which I mean I drank Guinness and did some writing at the Irish pub near my hotel before being in bed by 8:30.

The reason I was sticking around longer than Dan was because I had organised to have lunch with my agents Tara and Jerry on Monday. These are the two people responsible for changing my life almost overnight; Tara having sold the book rights to The Hunted and Jerry, visiting from LA, the one who sold the film. It was the first time I had met Jerry and it was great to be able to chat in person over lunch, to try and fail once again to adequately convey just how grateful I am to these two people.

The AACTA pitch and the lunch with Tara and Jerry feel, in some ways, symptomatic of the totally different speed my life seems to operate at these days. If you told me a year ago that I would be regularly flying to Sydney for pitches and meetings, that I would be sending emails back and forth with major Hollywood producers and some of the biggest publishers in the world, I would have laughed you off while desperately hoping you were right.

But in some ways the more things change the more they stay the same.

Next week Bitten By Productions’ new show, a revival of my 2016 comedy The Critic , opens at the Butterfly Club for Melbourne Fringe. I’m super excited about this; the cast and director are amazing and the rehearsals I’ve sat in on have been uniformly brilliant. But, of course, independent theatre is independent theatre, by which I mean there’s no money and lots of competition, particularly during Fringe. So my time-honoured techniques of guerrilla marketing come into play; namely spending the day running around the city surreptitiously sticking up posters and leaving flyers in obvious places in the hopes that more people will see them and come to see the play. It’s a very stark difference from being wined and dined by publishers and agents or getting on stage at major industry events.

But this, I guess, is my life now. For all that the most incredible and formerly inconceivable things have happened in the last six months, things just haven’t changed that much on a day to day basis. I still have my old commitments and I still have to trudge around trying to look casual while leaving flyers and posters in places I’m probably not supposed to.

I wouldn’t change it for the world.

Published on September 04, 2019 17:33

August 26, 2019

Fear and hunger

Quentin Tarantino famously insists that he will stop directing after his tenth film. His cited reason is that directors don’t get better with age, something he backs up by pointing to the demonstrably less vital late career work of various great auteurs. It’s hard to deny that he has a point; Steven Spielberg will always be Steven Spielberg, but there’s a huge gap between Jaws and Ready Player One.

I would never presume to guess what’s going through anyone’s mind, let alone Spielberg’s, but it has felt for a while like he’s reached a place in his career where he has nothing left to prove and so he’s no longer really trying. And honestly, that would be fair enough; there’s no way that Spielberg owes any more than what he’s already given. Yet it’s hard not to feel a little wistful for the time when a Spielberg film was synonymous with an instant classic.

It’s no secret that Bruce Springsteen is one of my biggest inspirations, and that has only been consolidated by the fact that he seems to be consistently challenging himself to explore new territory even as he enters his 70s. His most recent album, Western Stars, was initially sold as a return to his sparser acoustic efforts like Nebraska or The Ghost of Tom Joad, but in reality it’s something totally different, an introspective work of sweeping grandiosity, the haunting poetry of his lyrics elevated by the sort of soaring orchestral accompaniment he’s never really utilised before. Like it or not, there’s no mistaking Western Stars for any previous work of his. And beyond that, Springsteen is now using it as the platform for another artistic challenge, adapting the album into a concert film/documentary that looks likely to be a tear-jerker of immense power.

This, coming hot on the heels of not only his triumphant autobiography, but the beautiful work of self-reflection that was Springsteen on Broadway. He could easily spend the rest of his career dropping interchangeable albums and going on greatest hits tours but instead is swinging for the fences and trying new things. That, to me, is as exhilarating as it is rare to see from an artist of his age and stature. Springsteen has stayed hungry which is why for his fans a new project becomes an event of almost religious significance.

But outside of the devoted faithful, most would believe that Springsteen is past his prime. In truth it’s unlikely we’ll ever see another hit from him on the level of Born to Run or Born in the USA. Given his back catalogue I think that’s okay, but it does make me wonder how Springsteen himself feels about his old work compared to his new. Does he roll his eyes at the now 40-year-old naivete of Born to Run? Does he wish that he could capture that power and energy again? Or is the answer something a bit more complicated?

***

Back in high school I wrote as much as I do now – maybe even more. I would finish stories, become convinced they were straight up perfect, and then start sending them off to publishers and agents with predictably non-existent results. Within a year, I would be turning my nose up at those pieces, cringing anytime they were mentioned to me and promising everyone that I could write much better stuff now. This cycle of essentially disowning past works for being inferior went on for a long time.

In some ways, the tendency remains ingrained. When we decided to revive We Can Work It Out for Fringe last year, my first instinct was that the play would need some major overhauling, that it wouldn’t be representative of what I was now capable of. It was a surprise, then, to read over the script with a view to making changes only to find that by and large, I was happy with it. There were lines, concepts and developments that I wouldn’t write today, but that didn’t make them inherently bad. A couple of beats went or were tweaked, but otherwise it was the same text. A similar thing happened with The Critic this year, which is also returning for a Fringe run after doing well in 2016. Again I was sure I would need to rework the thing. Again I barely touched it. With both We Can Work It Out and The Critic I remain comfortable to share them as representative of my writing, even if, due to circumstances and shifting worldviews, I could write neither today. Does this, then, mean that I’ve reached a place where I’ve ‘developed’ enough as a writer to not cringe at old work even when it’s no longer as thematically relevant to me?

Not quite. We Can Work It Out was arguably the first good play I wrote, but I won’t let myself forget that it was put together around the same time as A Good German – the nadir of my work as a writer so far. Within months of each other, I was capable of writing both plays; one that I remain proud of, the other representing a low I never want to hit again. This fact precludes me from claiming some quantifiable shift in ability occurred around that time.

I think age and experience helps you be a little more discerning in knowing when a work is ready for public consumption, but it can only go so far. We never see our own stuff 100% clearly. And that, I think, is where a healthy combination of fear and hunger is your best friend. Hunger to challenge yourself, to jump higher hurdles, to try new things and wade into uncharted territory, but also fear of catastrophic failure, of another Good German.

Recently, delivering new drafts of both the manuscript and screenplay of The Hunted/Sunburnt Country, I was scared. I’d followed the notes I was given, but part of me was certain I’d got it wrong, that my reworkings had thrown off some integral but accidental balance in the text that was only the reason anyone liked it to begin with. Similarly, I’ve already finished the first draft of the sequel to The Hunted and yet as the first book gets closer to publication I’m finding myself almost paralysed with fear that the second will be laughed out of the building, that it’s too different to the first, that I’ve lost the alchemy and The Hunted was only a fluke.

And maybe those fears will be proved correct. But you know what? They also hold me to account. Fear means that I’ll only deliver the book when I’m confident that it’s the best I can make it. For this reason I now think that We Can Work It Out never represented the turning point in my writing; A Good German did. Because before failing on that level, I didn’t carry that secret fear of it ever happening again, that constant check on the easy assumption that something is good enough.

***

Fear of failure is universal to any artist trying to prove themselves. When Springsteen received the first pressing of Born to Run, he could listen to only a few minutes before he stormed out and threw it in the pool. The album was his last chance with a label looking to drop him, so he put everything he had into getting it right. The album, of course, was a masterpiece, but what lies under the perfectionism that led to its success was a deep and terrible fear that it would fail and ruin his career, fear that he couldn’t see past even when he heard the now-classic finished product. After Born to Run made him a legend, I doubt that fear was ever as strong again. How could it have been? Forty years later, Springsteen’s artistic ambition remains evident, but he’ll never again pour everything he has into making an album the best of all time. Born to Run’s brilliance was at least in part born of a necessity that no longer exists for him.

Maybe, then, Tarantino is wrong about age being the enemy of artists. I have to wonder if, in some ways, the biggest detriment to art is success. Consistent, regular success that slowly erodes your fears until you become comfortable that whatever you do will be good enough. Maybe dwindling ambition has a role to play as well, but if you’re no longer scared of failure I doubt you try as hard for victory.

I speak with minimal authority, but for what it’s worth I think that mix of fear and hunger is the artistic sweet spot. It doesn’t guarantee good work, but it makes it more possible.

I would never presume to guess what’s going through anyone’s mind, let alone Spielberg’s, but it has felt for a while like he’s reached a place in his career where he has nothing left to prove and so he’s no longer really trying. And honestly, that would be fair enough; there’s no way that Spielberg owes any more than what he’s already given. Yet it’s hard not to feel a little wistful for the time when a Spielberg film was synonymous with an instant classic.

It’s no secret that Bruce Springsteen is one of my biggest inspirations, and that has only been consolidated by the fact that he seems to be consistently challenging himself to explore new territory even as he enters his 70s. His most recent album, Western Stars, was initially sold as a return to his sparser acoustic efforts like Nebraska or The Ghost of Tom Joad, but in reality it’s something totally different, an introspective work of sweeping grandiosity, the haunting poetry of his lyrics elevated by the sort of soaring orchestral accompaniment he’s never really utilised before. Like it or not, there’s no mistaking Western Stars for any previous work of his. And beyond that, Springsteen is now using it as the platform for another artistic challenge, adapting the album into a concert film/documentary that looks likely to be a tear-jerker of immense power.

This, coming hot on the heels of not only his triumphant autobiography, but the beautiful work of self-reflection that was Springsteen on Broadway. He could easily spend the rest of his career dropping interchangeable albums and going on greatest hits tours but instead is swinging for the fences and trying new things. That, to me, is as exhilarating as it is rare to see from an artist of his age and stature. Springsteen has stayed hungry which is why for his fans a new project becomes an event of almost religious significance.

But outside of the devoted faithful, most would believe that Springsteen is past his prime. In truth it’s unlikely we’ll ever see another hit from him on the level of Born to Run or Born in the USA. Given his back catalogue I think that’s okay, but it does make me wonder how Springsteen himself feels about his old work compared to his new. Does he roll his eyes at the now 40-year-old naivete of Born to Run? Does he wish that he could capture that power and energy again? Or is the answer something a bit more complicated?

***

Back in high school I wrote as much as I do now – maybe even more. I would finish stories, become convinced they were straight up perfect, and then start sending them off to publishers and agents with predictably non-existent results. Within a year, I would be turning my nose up at those pieces, cringing anytime they were mentioned to me and promising everyone that I could write much better stuff now. This cycle of essentially disowning past works for being inferior went on for a long time.

In some ways, the tendency remains ingrained. When we decided to revive We Can Work It Out for Fringe last year, my first instinct was that the play would need some major overhauling, that it wouldn’t be representative of what I was now capable of. It was a surprise, then, to read over the script with a view to making changes only to find that by and large, I was happy with it. There were lines, concepts and developments that I wouldn’t write today, but that didn’t make them inherently bad. A couple of beats went or were tweaked, but otherwise it was the same text. A similar thing happened with The Critic this year, which is also returning for a Fringe run after doing well in 2016. Again I was sure I would need to rework the thing. Again I barely touched it. With both We Can Work It Out and The Critic I remain comfortable to share them as representative of my writing, even if, due to circumstances and shifting worldviews, I could write neither today. Does this, then, mean that I’ve reached a place where I’ve ‘developed’ enough as a writer to not cringe at old work even when it’s no longer as thematically relevant to me?

Not quite. We Can Work It Out was arguably the first good play I wrote, but I won’t let myself forget that it was put together around the same time as A Good German – the nadir of my work as a writer so far. Within months of each other, I was capable of writing both plays; one that I remain proud of, the other representing a low I never want to hit again. This fact precludes me from claiming some quantifiable shift in ability occurred around that time.

I think age and experience helps you be a little more discerning in knowing when a work is ready for public consumption, but it can only go so far. We never see our own stuff 100% clearly. And that, I think, is where a healthy combination of fear and hunger is your best friend. Hunger to challenge yourself, to jump higher hurdles, to try new things and wade into uncharted territory, but also fear of catastrophic failure, of another Good German.

Recently, delivering new drafts of both the manuscript and screenplay of The Hunted/Sunburnt Country, I was scared. I’d followed the notes I was given, but part of me was certain I’d got it wrong, that my reworkings had thrown off some integral but accidental balance in the text that was only the reason anyone liked it to begin with. Similarly, I’ve already finished the first draft of the sequel to The Hunted and yet as the first book gets closer to publication I’m finding myself almost paralysed with fear that the second will be laughed out of the building, that it’s too different to the first, that I’ve lost the alchemy and The Hunted was only a fluke.

And maybe those fears will be proved correct. But you know what? They also hold me to account. Fear means that I’ll only deliver the book when I’m confident that it’s the best I can make it. For this reason I now think that We Can Work It Out never represented the turning point in my writing; A Good German did. Because before failing on that level, I didn’t carry that secret fear of it ever happening again, that constant check on the easy assumption that something is good enough.

***

Fear of failure is universal to any artist trying to prove themselves. When Springsteen received the first pressing of Born to Run, he could listen to only a few minutes before he stormed out and threw it in the pool. The album was his last chance with a label looking to drop him, so he put everything he had into getting it right. The album, of course, was a masterpiece, but what lies under the perfectionism that led to its success was a deep and terrible fear that it would fail and ruin his career, fear that he couldn’t see past even when he heard the now-classic finished product. After Born to Run made him a legend, I doubt that fear was ever as strong again. How could it have been? Forty years later, Springsteen’s artistic ambition remains evident, but he’ll never again pour everything he has into making an album the best of all time. Born to Run’s brilliance was at least in part born of a necessity that no longer exists for him.

Maybe, then, Tarantino is wrong about age being the enemy of artists. I have to wonder if, in some ways, the biggest detriment to art is success. Consistent, regular success that slowly erodes your fears until you become comfortable that whatever you do will be good enough. Maybe dwindling ambition has a role to play as well, but if you’re no longer scared of failure I doubt you try as hard for victory.

I speak with minimal authority, but for what it’s worth I think that mix of fear and hunger is the artistic sweet spot. It doesn’t guarantee good work, but it makes it more possible.

Published on August 26, 2019 16:34

August 8, 2019

A slight change in circumstances

The day I found out I’d won the Sir Peter Ustinov award, I sat out on the deck of the house I lived in at the time and had a glass of wine with a friend. I explained to him what the award meant and where it could lead. A shining, glorious career was ahead of me, my creative success practically assured. I was about to become an in-demand writer and all the failures and disappointments that characterised the first half of my twenties would fade fast in the rearview mirror.

This friend, who tends to err on the side of cynical, listened in silence, then simply and honestly said ‘wow. So you’re set, then.’

I smiled, sipped my wine and agreed. Everything seemed certain and kept seeming certain for a long time after that. Even when the meetings that followed came and went without any tangible change in my life, I still believed that I was riding the wave of success. It probably took about a year for it to become clear to me that I was a lot less ‘set’ than I’d let myself assume.

There are various reasons for why things didn’t blow up the way I thought they would, but looking back the biggest one is that I just don’t think I was ready. Outside of the award winning Windmills pilot I didn’t have much else to offer when I went into meetings with producers, and beyond that my conception of what I wanted my career to be, the sort of writer I envisioned myself as, was vague and poorly defined. What I had been working towards was less a clear goal and more a kind of blurry notion of ‘making it’ without any realistic consideration of what that actually meant.

The Ustinov and its aftermath was a long, painful lesson in making assumptions. A few months ago, when initial interest came out of LA for the film adaptation of Sunburnt Country, my agent noted that I seemed very calm about what should have been mind blowing news. In truth, I was close to squealing with excitement – I just knew not to take anything for granted, that even certainties are a lot less certain than you might think in the creative industries. In retrospect, the Ustinov experience was preparatory for what was to come, a valuable learning curve about keeping a level head even when it seems like your dreams are coming true around you.

All of which brings me to the past week. You’ll have to excuse me being a little vague about things; some conversations are in such early stages and some projects aren’t able to be spoken about just yet, so I’m going to talk around a lot of what I’ve been doing and hope I arrive at the point I’m looking for.

Last Friday morning I flew to Sydney for a writers room job. Securing it was the work of my brilliant agent and it would be the first time I worked in a room over the course of several days, shoulder to shoulder with other writers as we developed the outline for a new TV show. The room, however, didn’t kick off until Monday; I was flying up early for a series of meetings at Harper Collins about the next stage of my book’s development.

That alone was a head-spinner. Seeing the passion from the team led to a mix of excitement and gnawing anxiety over when exactly they’re all going to realise that I have no clue what I’m doing. Their faith in the book and the scale on which it’s going to be promoted is mildly terrifying and I can’t wait. Of course, everything going smoothly relies on me holding up my end of the bargain; namely finishing the edits and getting the book to the highest possible standard before it goes to print. Flying up on Friday gave me Saturday and Sunday to wander around Sydney, stopping in at occasional pubs and cafes in order to keep working on the edits. By Sunday evening the major rewrites were all wrapped, right before I dove into a week of working on a very different project.

Editing the book is only one part of the ongoing Sunburnt Country/The Hunted (different names in different territories) experience. I’m also currently working on the next draft of the screenplay, which as has now been announced, is being developed by Stampede Ventures and Vertigo Entertainment in LA under the guiding hand of some of the biggest producers in Hollywood, including Greg Silverman – the former head of Warner Brothers. The film deal technically got underway before the book was sold, but I don’t think the size of the thing hit home for me until I saw the Variety and Deadline articles come out last week. For the first time it felt real. Add to this the fact that the other night I had dinner with a Stampede Executive over from LA and was given a bit more of an idea of what they have in mind for the film, including the timeline and potential talent involved. All of which left me with a panicky feeling of holy shit I have to finish this screenplay.

My plan was to get the script done in the evenings over last week in Sydney, but writers rooms are tiring and by the time you get out at the end of every day your brain is so stretched in so many different directions that giving any thought to a different project is nearly impossible. I therefore made the decision to focus on the room, do some screenplay notes if I found the energy but otherwise relegate the script to this week’s job. As much as I wanted to get it done, I don’t benefit anyone by rushing or not giving it my full attention.

The writers room was a fascinating experience, in its intensity, frustrations, and ultimate arrival at something really cool. I was comfortably the least experienced writer working on the show, and while it was a little intimidating to be working so closely with people who have been in the industry for a long time and have massive successes to their name, I never felt like my ideas weren’t being valued. Still, I was fairly exhausted by the time we wrapped on Friday and keen to get home and get back to work on the script. But over the course of the weekend, a couple of other things happened – nothing huge, but some potential movement, in one case on a project that I’d long since suspected would stay still indefinitely. I also found out that my TV concept Endgame (the name will change, thanks Avengers) is a finalist for a major pitching competition. If we win, we’ll get some development funding and support, which is thrilling but a little daunting from a time perspective. The pitching stage alone means another trip to Sydney before the month is out.

So yeah, things are hectic in the best way possible.

With so much tangible momentum on so many different fronts, am I starting to think that this is the belated realisation of that premature prophecy of being ‘set’? To be honest, I’m not thinking about it in those terms. Because as exciting as everything is, it’s also early days. Some high profile stuff has happened and I no longer have to do freelance gigs in order to support myself financially, but that doesn’t mean my career has erupted in a way that’s necessarily viable in the long term. Obviously I hope that’s the case and I think it’s fair enough that I’m optimistic, but I’ll never forget that, as I learned after the Ustinov, nothing has happened until it has happened. I strongly believe that one of the keys to creative success is a balance of realism and almost deluded hopefulness. I really hope every exciting seed that has been planted recently grows big and strong, but at this stage who knows? For now, I’m enjoying the ride but remembering to hold on tight and keep one eye on the ground.

This friend, who tends to err on the side of cynical, listened in silence, then simply and honestly said ‘wow. So you’re set, then.’

I smiled, sipped my wine and agreed. Everything seemed certain and kept seeming certain for a long time after that. Even when the meetings that followed came and went without any tangible change in my life, I still believed that I was riding the wave of success. It probably took about a year for it to become clear to me that I was a lot less ‘set’ than I’d let myself assume.

There are various reasons for why things didn’t blow up the way I thought they would, but looking back the biggest one is that I just don’t think I was ready. Outside of the award winning Windmills pilot I didn’t have much else to offer when I went into meetings with producers, and beyond that my conception of what I wanted my career to be, the sort of writer I envisioned myself as, was vague and poorly defined. What I had been working towards was less a clear goal and more a kind of blurry notion of ‘making it’ without any realistic consideration of what that actually meant.

The Ustinov and its aftermath was a long, painful lesson in making assumptions. A few months ago, when initial interest came out of LA for the film adaptation of Sunburnt Country, my agent noted that I seemed very calm about what should have been mind blowing news. In truth, I was close to squealing with excitement – I just knew not to take anything for granted, that even certainties are a lot less certain than you might think in the creative industries. In retrospect, the Ustinov experience was preparatory for what was to come, a valuable learning curve about keeping a level head even when it seems like your dreams are coming true around you.

All of which brings me to the past week. You’ll have to excuse me being a little vague about things; some conversations are in such early stages and some projects aren’t able to be spoken about just yet, so I’m going to talk around a lot of what I’ve been doing and hope I arrive at the point I’m looking for.

Last Friday morning I flew to Sydney for a writers room job. Securing it was the work of my brilliant agent and it would be the first time I worked in a room over the course of several days, shoulder to shoulder with other writers as we developed the outline for a new TV show. The room, however, didn’t kick off until Monday; I was flying up early for a series of meetings at Harper Collins about the next stage of my book’s development.

That alone was a head-spinner. Seeing the passion from the team led to a mix of excitement and gnawing anxiety over when exactly they’re all going to realise that I have no clue what I’m doing. Their faith in the book and the scale on which it’s going to be promoted is mildly terrifying and I can’t wait. Of course, everything going smoothly relies on me holding up my end of the bargain; namely finishing the edits and getting the book to the highest possible standard before it goes to print. Flying up on Friday gave me Saturday and Sunday to wander around Sydney, stopping in at occasional pubs and cafes in order to keep working on the edits. By Sunday evening the major rewrites were all wrapped, right before I dove into a week of working on a very different project.

Editing the book is only one part of the ongoing Sunburnt Country/The Hunted (different names in different territories) experience. I’m also currently working on the next draft of the screenplay, which as has now been announced, is being developed by Stampede Ventures and Vertigo Entertainment in LA under the guiding hand of some of the biggest producers in Hollywood, including Greg Silverman – the former head of Warner Brothers. The film deal technically got underway before the book was sold, but I don’t think the size of the thing hit home for me until I saw the Variety and Deadline articles come out last week. For the first time it felt real. Add to this the fact that the other night I had dinner with a Stampede Executive over from LA and was given a bit more of an idea of what they have in mind for the film, including the timeline and potential talent involved. All of which left me with a panicky feeling of holy shit I have to finish this screenplay.

My plan was to get the script done in the evenings over last week in Sydney, but writers rooms are tiring and by the time you get out at the end of every day your brain is so stretched in so many different directions that giving any thought to a different project is nearly impossible. I therefore made the decision to focus on the room, do some screenplay notes if I found the energy but otherwise relegate the script to this week’s job. As much as I wanted to get it done, I don’t benefit anyone by rushing or not giving it my full attention.

The writers room was a fascinating experience, in its intensity, frustrations, and ultimate arrival at something really cool. I was comfortably the least experienced writer working on the show, and while it was a little intimidating to be working so closely with people who have been in the industry for a long time and have massive successes to their name, I never felt like my ideas weren’t being valued. Still, I was fairly exhausted by the time we wrapped on Friday and keen to get home and get back to work on the script. But over the course of the weekend, a couple of other things happened – nothing huge, but some potential movement, in one case on a project that I’d long since suspected would stay still indefinitely. I also found out that my TV concept Endgame (the name will change, thanks Avengers) is a finalist for a major pitching competition. If we win, we’ll get some development funding and support, which is thrilling but a little daunting from a time perspective. The pitching stage alone means another trip to Sydney before the month is out.

So yeah, things are hectic in the best way possible.

With so much tangible momentum on so many different fronts, am I starting to think that this is the belated realisation of that premature prophecy of being ‘set’? To be honest, I’m not thinking about it in those terms. Because as exciting as everything is, it’s also early days. Some high profile stuff has happened and I no longer have to do freelance gigs in order to support myself financially, but that doesn’t mean my career has erupted in a way that’s necessarily viable in the long term. Obviously I hope that’s the case and I think it’s fair enough that I’m optimistic, but I’ll never forget that, as I learned after the Ustinov, nothing has happened until it has happened. I strongly believe that one of the keys to creative success is a balance of realism and almost deluded hopefulness. I really hope every exciting seed that has been planted recently grows big and strong, but at this stage who knows? For now, I’m enjoying the ride but remembering to hold on tight and keep one eye on the ground.

Published on August 08, 2019 23:57

July 10, 2019

How it happened.

The first hint of what was about to happen came quietly a few months ago. I’d been visiting an old friend and was walking home alone up an empty road when I felt something both familiar and new.

Years ago, when I was in the midst of writing what would become the Boone Shepard trilogy, there were moments when I would sense with quiet certainty that I wasn’t alone. That Boone was standing just out of my field of vision, tapping his foot and wondering when we were going to get back to our adventures. These instances weren’t the first time I’d felt this. In 2009, writing the very first draft of Windmills, I spent the day after finishing a pivotal scene with the uncomfortable feeling that protagonist Leo Grey was following me. It wasn’t something I articulated to anyone. I just kind of accepted it; whether a trick of the mind or something else, the characters you embark on a journey with make themselves known to you. They’re your companions until, as I learnt in the case of Boone, you reach the end of the line and have to say goodbye, finding yourself faced with a particular sorrow that you never could have anticipated.

Anyway. This night, not long ago, came several months after I had seen Boone for the last time. And as I was walking home, I felt someone new at my shoulder. It wasn’t Boone; Boone stumbled and tripped along. It wasn’t Leo, who tended to lurk in the shadows. This was someone prowling and confident, someone who exuded danger and made me feel, on this empty road late at night, that I was about as protected as I could be.

***

I knew Sunburnt Country was a gamble the moment I hit send. A brutal, visceral expansion of a novella I wrote in 2017, it was unlike any of my other projects and it was for that reason that I thought it might be exactly what I needed.

About a year previously I had been put in touch with Tara Wynne, a brilliant agent at the venerable and prestigious Curtis Brown. Tara read some of my work and while she liked it, she felt that both of the novels I had sent her weren’t quite ready. Looking at what else I had, I decided to move ahead with Sunburnt Country. I figured it would either help illustrate my range or prompt Tara to politely ask me to leave her alone. I rolled the dice and was almost certain I had made a mistake. It was too violent, too gratuitous, too weird. There was no way Curtis Brown would go for it.

They went for it.

Even when Tara told me she would be interested in representing it after a few changes, I was still doubtful. This seemed to have happened too quickly and too easily – Curtis Brown are one of the best agencies in the country, representing a variety of famous Australian bestsellers. The notion that I might join their ranks was giving me a serious bout of imposter syndrome. But I pushed ahead, I made the changes and sent the novel back. I was ready to receive a response telling me it still wasn’t ready. What I got was a contract.

The speed with which things happened after that still makes my head spin. Within a day of signing with Curtis Brown, Sunburnt Country went out to Jerry Kalajian, an LA agent who specialises in selling the film rights to major novels. He read Sunburnt Country in one sitting and loved it. In our first conversation he started bringing up the kind of big names that made me gape at the phone, not least when he told me he would be sending them the book that night.

In the meantime, Sunburnt Country went out to several Australian publishers and I started playing the waiting game. I managed to discipline myself into only checking my emails every fifteen minutes. I didn’t want to annoy Tara with hourly queries about how everything was going, but I was desperate to know what was happening. When a couple of quiet weeks passed and Tara got back to me saying that there had been a handful of passes, disappointment started to close in. Despite my best efforts, I had gotten carried away with the thrilling possibilities, but of course, just because some people liked the book didn’t mean the publishers and producers who actually had to front up the money would.

Then came the first email from an interested publisher. Then the second. And the third. And a phone call with a major producer in LA interested in the rights.

Suddenly I was in the middle of a whirlwind. I took lunch with the publishers behind some of Australian literature’s biggest recent success stories. I flew to Sydney to hear pitches in boardrooms overlooking the city. I was sent emails keeping me up to date with contract negotiations in LA, emails discussing the kind of money I’d never even seen in my life.

The film option was secured. And following it came the publishing offers. Several of them, meaning I had to make a very hard choice. Everyone I met with would have been an incredible publisher for my book. In the end though, it had to be Harper Collins. They had gone above and beyond in their pitch, sending me a 27-page document full of striking, sun beaten imagery that took me through how much they loved the book and what their vision for it was. They wanted the novel, they got the novel, and they were already talking sequel potential. In fact, they were sure of it; theirs was a two-book offer.

So I accepted. A contract was negotiated. I signed and sent it off. And like that, it was official. My next two books would be published by one of the biggest publishers on the planet. The whole process, from signing with Curtis Brown to sending off the publishing contract, had barely taken two months.

Except it took a lot longer than that. I’ve dreamed of this moment my whole life, and pretty much everything I’ve ever done in the sphere of writing has been working towards it. None of it would have happened if it wasn’t for the dumb mistakes and the minor successes I had along the way, from my theatre work to podcasting, from self-publishing Windmills to seeing Boone Shepard’s final adventure hit shelves, from studying screenwriting to winning the Ustinov. Everything was a means to an end that, now it’s here, I realise is very far from an end.

It took years. It took countless failures and just enough successes to keep my head above water. And it took the support of the people who believed in me from the start, despite me giving them very little reason to. I hope you know how grateful I am. Because God knows I haven’t always been worthy of your support.

To be honest, I’m still not sure I am. I’m still terrified I’m going to screw all of this up somehow, that I won’t know how to manage it and I’ll make some rookie error that will send everything careening off the deep end. But I’m going to do my absolute best not to.

***

When, walking up that empty road, I felt this new presence behind me, I grinned. I didn’t know, in that moment, what was going to happen. But on some level, I knew things were heading in the right direction. I knew I had somebody steering me who knew what they were doing, who, like Boone before, would be my guide to the years ahead.

In July 2020, this character will walk out into the world, as their first story is released and a whole new adventure starts.

I can’t wait for you to meet her.

Years ago, when I was in the midst of writing what would become the Boone Shepard trilogy, there were moments when I would sense with quiet certainty that I wasn’t alone. That Boone was standing just out of my field of vision, tapping his foot and wondering when we were going to get back to our adventures. These instances weren’t the first time I’d felt this. In 2009, writing the very first draft of Windmills, I spent the day after finishing a pivotal scene with the uncomfortable feeling that protagonist Leo Grey was following me. It wasn’t something I articulated to anyone. I just kind of accepted it; whether a trick of the mind or something else, the characters you embark on a journey with make themselves known to you. They’re your companions until, as I learnt in the case of Boone, you reach the end of the line and have to say goodbye, finding yourself faced with a particular sorrow that you never could have anticipated.

Anyway. This night, not long ago, came several months after I had seen Boone for the last time. And as I was walking home, I felt someone new at my shoulder. It wasn’t Boone; Boone stumbled and tripped along. It wasn’t Leo, who tended to lurk in the shadows. This was someone prowling and confident, someone who exuded danger and made me feel, on this empty road late at night, that I was about as protected as I could be.

***

I knew Sunburnt Country was a gamble the moment I hit send. A brutal, visceral expansion of a novella I wrote in 2017, it was unlike any of my other projects and it was for that reason that I thought it might be exactly what I needed.

About a year previously I had been put in touch with Tara Wynne, a brilliant agent at the venerable and prestigious Curtis Brown. Tara read some of my work and while she liked it, she felt that both of the novels I had sent her weren’t quite ready. Looking at what else I had, I decided to move ahead with Sunburnt Country. I figured it would either help illustrate my range or prompt Tara to politely ask me to leave her alone. I rolled the dice and was almost certain I had made a mistake. It was too violent, too gratuitous, too weird. There was no way Curtis Brown would go for it.

They went for it.

Even when Tara told me she would be interested in representing it after a few changes, I was still doubtful. This seemed to have happened too quickly and too easily – Curtis Brown are one of the best agencies in the country, representing a variety of famous Australian bestsellers. The notion that I might join their ranks was giving me a serious bout of imposter syndrome. But I pushed ahead, I made the changes and sent the novel back. I was ready to receive a response telling me it still wasn’t ready. What I got was a contract.

The speed with which things happened after that still makes my head spin. Within a day of signing with Curtis Brown, Sunburnt Country went out to Jerry Kalajian, an LA agent who specialises in selling the film rights to major novels. He read Sunburnt Country in one sitting and loved it. In our first conversation he started bringing up the kind of big names that made me gape at the phone, not least when he told me he would be sending them the book that night.

In the meantime, Sunburnt Country went out to several Australian publishers and I started playing the waiting game. I managed to discipline myself into only checking my emails every fifteen minutes. I didn’t want to annoy Tara with hourly queries about how everything was going, but I was desperate to know what was happening. When a couple of quiet weeks passed and Tara got back to me saying that there had been a handful of passes, disappointment started to close in. Despite my best efforts, I had gotten carried away with the thrilling possibilities, but of course, just because some people liked the book didn’t mean the publishers and producers who actually had to front up the money would.

Then came the first email from an interested publisher. Then the second. And the third. And a phone call with a major producer in LA interested in the rights.

Suddenly I was in the middle of a whirlwind. I took lunch with the publishers behind some of Australian literature’s biggest recent success stories. I flew to Sydney to hear pitches in boardrooms overlooking the city. I was sent emails keeping me up to date with contract negotiations in LA, emails discussing the kind of money I’d never even seen in my life.

The film option was secured. And following it came the publishing offers. Several of them, meaning I had to make a very hard choice. Everyone I met with would have been an incredible publisher for my book. In the end though, it had to be Harper Collins. They had gone above and beyond in their pitch, sending me a 27-page document full of striking, sun beaten imagery that took me through how much they loved the book and what their vision for it was. They wanted the novel, they got the novel, and they were already talking sequel potential. In fact, they were sure of it; theirs was a two-book offer.

So I accepted. A contract was negotiated. I signed and sent it off. And like that, it was official. My next two books would be published by one of the biggest publishers on the planet. The whole process, from signing with Curtis Brown to sending off the publishing contract, had barely taken two months.

Except it took a lot longer than that. I’ve dreamed of this moment my whole life, and pretty much everything I’ve ever done in the sphere of writing has been working towards it. None of it would have happened if it wasn’t for the dumb mistakes and the minor successes I had along the way, from my theatre work to podcasting, from self-publishing Windmills to seeing Boone Shepard’s final adventure hit shelves, from studying screenwriting to winning the Ustinov. Everything was a means to an end that, now it’s here, I realise is very far from an end.

It took years. It took countless failures and just enough successes to keep my head above water. And it took the support of the people who believed in me from the start, despite me giving them very little reason to. I hope you know how grateful I am. Because God knows I haven’t always been worthy of your support.

To be honest, I’m still not sure I am. I’m still terrified I’m going to screw all of this up somehow, that I won’t know how to manage it and I’ll make some rookie error that will send everything careening off the deep end. But I’m going to do my absolute best not to.

***

When, walking up that empty road, I felt this new presence behind me, I grinned. I didn’t know, in that moment, what was going to happen. But on some level, I knew things were heading in the right direction. I knew I had somebody steering me who knew what they were doing, who, like Boone before, would be my guide to the years ahead.

In July 2020, this character will walk out into the world, as their first story is released and a whole new adventure starts.

I can’t wait for you to meet her.

Published on July 10, 2019 01:22

May 29, 2019

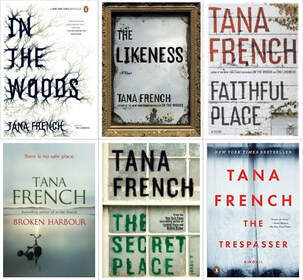

Why The Dublin Murder Squad might be the best book series I’ve ever read

My favourite play of all time is Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane, for a couple of reasons. Not only is it a deft combination of laugh out loud funny and gut-punch devastating, but it is only the first part of a trilogy of plays, all set in the same town, all standalone stories and yet all stories that enrich each other if you read/watch them in sequence, due to the new perspective each instalment gives you on characters and events you thought you had a handle on. The Leenane Trilogy is a singular storytelling experience because each play is satisfying by itself and yet together they create a powerful portrait of a small-town Ireland in despair, a sense of a lived in world that led me, when I was in Ireland two years ago, to go out of my way to visit the real town of Leenane, just to feel like I was stepping into the world of some of my favourite ever stories.

My favourite play of all time is Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane, for a couple of reasons. Not only is it a deft combination of laugh out loud funny and gut-punch devastating, but it is only the first part of a trilogy of plays, all set in the same town, all standalone stories and yet all stories that enrich each other if you read/watch them in sequence, due to the new perspective each instalment gives you on characters and events you thought you had a handle on. The Leenane Trilogy is a singular storytelling experience because each play is satisfying by itself and yet together they create a powerful portrait of a small-town Ireland in despair, a sense of a lived in world that led me, when I was in Ireland two years ago, to go out of my way to visit the real town of Leenane, just to feel like I was stepping into the world of some of my favourite ever stories.I’d never known anything like those plays and would recommend them heartily to anyone who would listen. Most of the time I got half-hearted nods or a vague ‘guess I’ll check them out’. One time, however, the response was ‘oh, that sounds a lot like the Dublin Murder Squad books by Tana French’.

I’m not somebody who rushes out to seek stories similar to ones I’ve previously enjoyed, and while I made vague noises of my own about how I might check out that series, I remembered it and when I came across the first book, In The Woods in a second hand bookstore earlier this year, I figured I might as well give it a try.

What followed was revelatory. What is about to follow is my spoiler-free post-mortem of the whole series, why I loved it, and why you should read it. But if you want the short version, I finally found something I could be as effusive about as the Leenane Trilogy. It turned out all I needed was another Irish series of standalone stories set in the same universe with each instalment giving new context to the ones that preceded it. Who’d have thought?

In The Woods