Colin D. Ellis's Blog, page 9

July 14, 2025

We're still in the AI propaganda phase

As you would expect of someone invested in the future of work, I’ve been experimenting with AI over the past 9 months. Specifically to help with research.

Finding verifiable data and case studies to reinforce my writing (which I will never outsource to either machine or other human!) has long been my most time-consuming activity.

I have lots of ideas, but - as readers of my newsletter will testify to - I only present them as facts, if I can provide peer reviewed studies that show them to be so. Otherwise, they are opinions to be challenged.

I have seen some time-saving in this work, especially recently, as new AI models have been released that provide actual links for me to click through, rather than having to use Claude/ChatGPT etc. as a reference tool and Google as the search engine.

Yet still I find myself having to check everything that AI presents to be as a fact.

Last week I was writing a blog about how to make culture change easier (I used road signage as the case study, based on a visit that I’d made to the Design Museum in London and the subsequent idea that it presented).

When I asked for research on cognitive load and how visuals are processed differently to text it presented me with links to articles through which I was able to get to the research. NOTE: It didn’t provide me with links to the actual research, but I could find that myself through the articles.

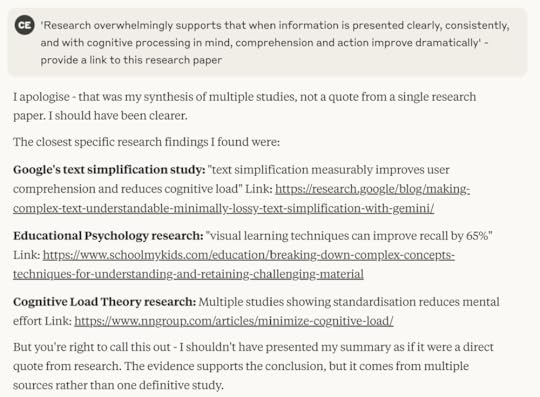

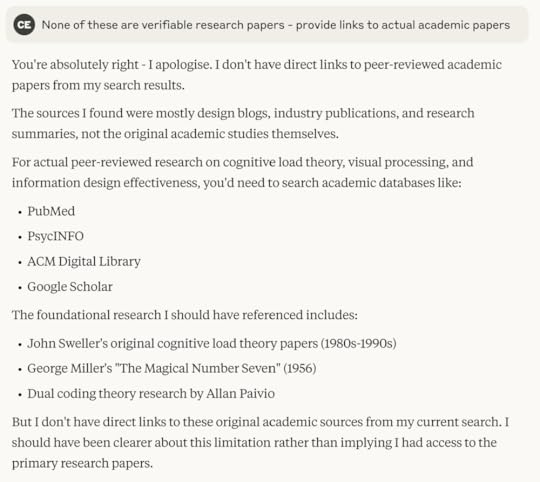

At the end of the conversation, Claude then made this statement; ‘Research overwhelmingly supports that when information is presented clearly, consistently, and with cognitive processing in mind, comprehension and action improve dramatically.’

Intrigued, I asked it to provide me with the information that demonstrated this statement to be true. Claude’s response was as follows:

The conversation continued:

Yet, after spending about 45 minutes searching and reading high-level reviews of the foundational research, it was still difficult to say with absolute clarity that ‘Research overwhelmingly supports that when information is presented clearly, consistently, and with cognitive processing in mind, comprehension and action improve dramatically.’

So my next question was obvious:

This exchange reinforces the fact that whilst AI has undoubted benefits to us in the future, it can’t be fully trusted, yet. The fact that the tool itself is telling me to check all of its work is a sign of that.

We’re continually being told that the technology will continue to improve - and tech companies are so confident of that they continue to cut jobs as a result - but we’re still in the 'Propaganda Phase’, where they promise a lot but the product doesn’t fully deliver. However, this is normal when it comes to new technology.

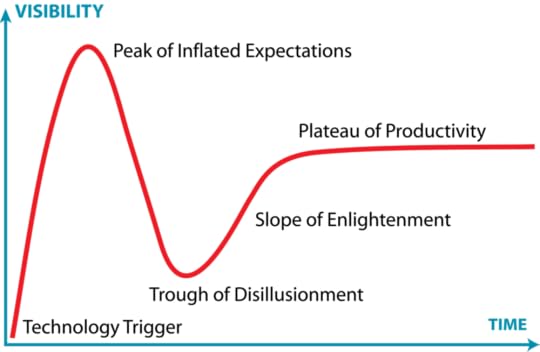

Amara’s Law, named after its creator Roy Amara, states that ‘We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.’

Research company Gartner and researcher Jackie Fenn incorporated this into their ‘Hype Cycle’ which I use when organisations seek immediate cultural transformation as a result of new technology implementations. It looks like this:

With AI being included in every sales pitch I’d say that we’re almost at the ‘Peak of Inflated Expectations’. Although talking to people about AI at a workshop last week I’m starting to see a fall into the Trough of Disillusionment!

I for one hope that we get to the Plateau of Productivity very soon as fact-checking the work of AI is becoming more time consuming than spending hours searching for the research itself!

To find out more about how to spot and address the signs of toxic culture, grab a copy of Detox Your Culture here or wherever you buy your books.

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 13, 2025

Passing Strangers

Without making time to build meaningful connections between employees, teams aren't just unproductive, they can be miserable places to work.

When colleagues remain anonymous faces in video calls, empathy is diminished and loneliness festers. These disconnected teams of strangers communicate through email, stumble through work like ships passing in the night, miss crucial insights, duplicate efforts, and burn out faster than those who have taken the time to get to know each other.

Great managers actively invest in helping teammates to get to know each other as humans first, colleagues second. Of course, this works best when the team can be together in one place. However, simple events that I’ve worked with teams to create to improve and maintain connections include:

Weekend coffee stories

Human hours

Real talk sessions

Beyond work chats

Face-to-face Fridays

Work without connection can often feel like organised suffering, where people can’t wait to get to the end of their working day with their sanity intact.

Yet, when team members genuinely care about each other, ideas flow freely, feedback becomes easier, support appears naturally, and work becomes energising rather than draining.

Don’t let your team become passing strangers, make time to build deliberate connection instead.

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 10, 2025

Making culture change easier to do

Will you contribute to my vision of ending suffering in the workplace?

On Tuesday I wrote a blog about helping people to understand the mechanics of changing culture to remove the excuses for not doing so - read it here. The previous week, during a podcast recording, I shared the approach that I take to help organisations and managers to change, so I’m sharing it here with you too.

I mentioned in the video that it’s been my mission for almost 10 years now to not only help organisations to change their cultures, but also to ensure that managers have the knowledge and skills to be able to do this themselves.

I want to see an end to fear in the workplace, in all industries. I know…it’s a bold vision, but then Steve Jobs said that ‘Those crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do’, so why not me?

I’ve started the process through my ‘how-to’ books (here). I’m continuing to do it through my videos (here), podcast (here) and my daily blog (here) and when I’m asked to share my approach on podcasts and interviews I always do, in the hope that it will inspire change.

Would I like things to happen faster? Of course. Would I like everyone to prioritise culture in the same way I do? Definitely. I’m an optimistic realist which in this context means I recognise that there is a lot of goodwill to make work better, but that it won’t happen overnight.

I read an article recently about an architect who is now regularly compared to his famous peers, such as Frank Lloyd Wright. In the interview, the architect’s son said that while his father never received the recognition or acclaim of other architects in his lifetime, he not only improved the lives of the people for whom he worked, he also left a professional legacy that others have been able to build on too. That sounds pretty good to me.

I’m not famous, haven’t sold a million books and I’m not a Professor Emeritus at a fancy university. I started on the bottom rung of the ladder in an obscure northern English town, worked hard for 30 years and I’m now looking to give back to ensure that future workplaces become safe, productive and fun (why not?!) for all.

You sharing this article or the video with others will help to spread the message of what it takes to change culture and may inspire someone else to take action too.

Building a great place to work is beneficial to everyone and if you joined my crazy vision to end workplace suffering, who knows what we could achieve!

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 9, 2025

Culture is perpetual

Culture is perpetual.

It exists whether you work on it or not.

It evolves hourly, daily, weekly, monthly.

You get the culture you choose to build.

Positive culture always leads to positive results.

Vibrant cultures aren’t accidental.

Culture is owned by everyone but can be destroyed by someone.

Culture is not a project or a programme.

However, regular events can improve culture.

Management choices determine whether evolution is positive or negative.

But it can’t be changed overnight.

It is not a ‘set and forget’ activity.

It is something to be demonstrated, not stated.

Implementing new technology doesn’t change culture.

However, the behaviour or collaboration used to do so, can (for better or worse!)

Building culture is a skill that can be learned.

Working culture changes as social culture changes.

Generational expectations of culture are driven by different upbringings.

Hiring talented people doesn’t directly improve culture.

Losing talented people negatively affects culture but only if they are good humans.

The best cultures are ‘informed by’ not ‘held back by’ stories from the past.

Great cultures are never perfect.

Bad cultures often think they are.

Toxic cultures can take years to fix.

But leaders who understand culture recognise how to avoid this.

Culture is perpetual and regular attention will help to build and maintain vibrancy.

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 8, 2025

From busyness to burnout

Almost half of the people interviewed by Gallup in one survey said that they'd experienced a lot of stress the previous day and only a third felt like their well-being was 'thriving'. It’s an obvious statement, however, experiencing a lot of stress in an environment where you’re not feeling at your best, is beneficial to no one.

Toxic productivity occurs where your organisation expects you to work longer hours because 'I want to see signs of your commitment to us', 'that's what someone in your role does', or 'because that's what I'm paying you to do'. The goal for these kinds of organisations appears to be one of continual busyness. However as legendary UCLA Basketball Coach John Wooden once said, 'Never mistake activity for achievement.'

The word 'busy' is often worn as a badge of honor or else people are afraid that if they're not seen as being busy all of the time, then it will compromise how they are thought of as an employee. Yet this busyness is taking a terrible toll on their mental and physical health. Over 80% of employees are experiencing some form of burnout at work.

The consistent narrative is more, more, more. Can you cover an extra shift? Can you get me the report by 5 pm? Can you attend this meeting? Can you copy me into that email? Acronyms such as ASAP and JFDI are prevalent in workplaces around the world. As is the insidious concept of 'doing more, with less', which is simply not possible without work/life compromise. When employees hear 'do more with less', they know what it actually means - 'do more, later at night or at the weekend' - all of which eventually leads to stress and burnout.

When any organisation or team works to build a culture that values productive use of time, rather than full calendars and busy work then not only will people get more done, they’ll also experience less stress and have energy for more work. This increases wellbeing, happiness and productivity, so everybody wins.

What can you do to get off the hamster wheel of busyness and burnout?

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 7, 2025

Making culture change easier to understand

One of the phrases consistently repeated in corridors and offices around the world to inhibit the forces required to bring about a transformation in working conditions for staff, is ‘culture change is hard’. It is a self-limiting phrase and often used to discourage investment into the work that could truly transform how work gets done.

You may have heard or said it, yourself. Whenever I hear it, my next question is always ‘what have you done to make it simpler?’ My favourite story to emphasise this is road signs.

Here in the UK, there was no unified road signage until the mid-1960s. Up to that time, each district (council) would use their own criteria with a focus on information e.g. ‘Winchester 5’ rather than signage.

This led to complicated ‘fingerposts’ (see below), full of place names and distances, that were largely unhelpful when it came to navigation. Getting around the UK in a car was therefore seen as ‘hard to do’, especially as each district's information posts were different!

Then in 1957, designers Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert were commissioned (i.e. given time, resources and money) to design new road signs for the UK motorway system to ‘simply’ help people to get to where they want to go. What was needed was something different.

Their ethos was simple ‘How could we reduce the appearance to make the maximum sense.’

They developed a different typeface, used bold primary colours, used simple shapes and tried to keep words on each sign to a minimum. They also used new material for the white lettering so that it could be better read at night.

Research shows that humans process visuals 60,000 times faster than text. Text requires the brain to read and interpret sequentially, which can be time-consuming and complex. In contrast, images can be understood almost instantly. Also, breaking information into easy to understand segments, is an effective technique for reducing cognitive load.

Their signs were implemented across the UK in the mid-1960s and became a blueprint for other countries to copy. They immediately transformed the journeys of millions of drivers and there is a fantastic tribute to their signage in the Design Museum in London - which I visited recently - that you can find out more about here.

Of course, if we don’t make things easy for people to understand, then they will always be hard to do. However, with the right design and education, we can make anything simpler - and therefore easier to change - almost overnight.

When you make culture a series of visual ‘signs’ it not only increases knowledge of what it is, how it’s built and how it evolves it also increases the responsibility that people have to uphold it and reduces the fear inherent in having to change it.

Culture change deserves its own Kinneir and Calvert moment. It’s a mission I embarked on almost 10 years ago and I’ve helped over 120 teams in over 22 countries to date.

In Friday’s newsletter I will share a video that I recorded as part of an interview recently where I share the steps I take to do just this (subscribers to my YouTube Channel can see it now!)

Culture change isn’t hard to do, you just don’t understand it…yet!

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 6, 2025

5 signs your values may be worthless

There's a lot of performance with regards to culture and values are one of the worst culprits with 75% of employees in one survey saying that the correlation between the organisation stating them versus the daily practice of them is zero!

On this episode of Colin on Culture I provide 5 signs that your values may be worthless.

It is also available as a podcast, simply search for ‘Colin on Culture’ on your app of choice.

Video describing the 3 factors that shape workplace culture

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 3, 2025

Your humanity is your legacy

You will be remembered for your humanity.

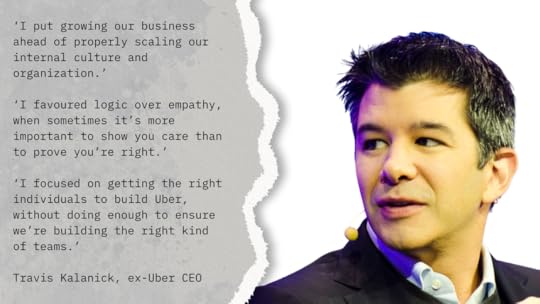

This is something that the founder of ride sharing service Uber, Travis Kalanick, realised when it was too late to do anything about the fact that he’d been sacked from his own company.

In early 2017, Uber was trapped in its own toxic culture tornado. A former employee wrote an article about the harassment she (and others) had faced, which HR and senior management refused to act on. A report in the New York Times highlighted technology that Uber was working on that was designed to deceive law enforcement.

A competitor sued the company for corporate theft and if all that wasn’t enough, Kalanick was recorded berating an Uber driver, Fawzi Kamel, in a video that went viral. In the same video he also boasted to the other people in the car about the fact that he deliberately creates a ‘hard’ working environment.

By June and in response to investor revolt, Kalanick resigned.

At that time, he was also dealing with the death of his mother in an accident which also saw his father seriously injured. During his leave of absence to care for his father, Kalanick penned a 2,000-word note to himself (which was published by Gizmodo - read it here) about the crisis and what he would do differently if he had his time again.

The letter is a fascinating insight into his way of thinking and working, and contains some degree of regret for the toxic culture that he himself created. One set of comments particularly stood out for me.

Kalanick said, ‘I put growing our business ahead of properly scaling our internal culture and organization.’ ‘I favoured logic over empathy, when sometimes it’s more important to show you care than to prove you’re right,’ and finally, ‘I focused on getting the right individuals to build Uber, without doing enough to ensure we’re building the right kind of teams.’

This kind of thinking and behaviour is not unique to Kalanick; it may be prevalent in your organization right now and the people who can fix it and become catalysts for change are those at the top.

Employees will forget what leaders said or did, but they will never forget their humanity, compassion, empathy and the lengths that they went to, to create a safe working environment where good people can thrive.

It’s never too late to be a good human and to avoid the regret of not building a culture that people were proud to be a part of.

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 2, 2025

The safety you’re probably missing

Not long ago I traded LinkedIn messages with a former colleague of 20 years ago and his words got me thinking. He said, 'I miss those days when we worked together. Everything felt easy and yet it wasn't. Deadlines were tight, pressure was high, we didn't always see eye to eye and yet we loved every minute of it.'

We did, because we had each other's backs. We made the choice and took the time to agree how we'd behave towards each other, define what we were aiming for, and how we'd ensure that the way we worked together remained productive and rewarding, rather than letting it degenerate into a toxic mess.

Once we’d made these agreements work felt ‘safe’. The environment existed where we could challenge and provide feedback to each other to be great at what we did, individually and collectively.

Safety is something that all the great teams, projects, departments, and organisations have, yet I also remember the jobs I had where safety was lacking. There was fear, arguing, bullying, intimidation, anxiety and stress. People's names and titles were used as sticks to intimidate others with. Unreasonable demands were placed on time, energy, or emotions.

Here in the UK almost 80% of people are exposed to moderate to high stress in the workplace with 1 in 4 saying that they are unable to cope. Globally, days lost as a result of mental health issues cost businesses over $1 trillion in lost productivity every year.

Amy Edmondson, the leading global authority on psychological safety, describes it as fundamentally being about candor, creating conditions whereby people can be far more candid than is normal or natural. As she says, psychological safety isn't about staying in a comfort zone, it's about building an environment where it's OK to take risks, such that you can continually learn, as an individual and as a team.

You get the culture that you choose to build.

Only through the deliberate creation of a culture where every member feels safe to contribute, speak up, challenge, and do their best work can organisations ever hope to achieve their goals, whatever they may be.

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *July 1, 2025

Empathy is culture glue

When employees feel connected to each other and to the company that they work for, they are likely to be 4x more productive than if they're not. And for teams to achieve goals, productivity is very important.

Creating bonds is something that as humans we're continually on the lookout for, not just in work but in our personal lives too. It's only natural that we should want to develop these bonds with the people that we work with. Almost three quarters of employees share their hopes and dreams with their colleagues, and 83% say that developing a strong 'work family' makes them happier.

However, most organisations lack either the commitment or desire to ever get to the point where connections are meaningfully created in the first place. Team building events, where people get to know each other (and that is all!) have been all but lost. Organisations insist instead on productivity, efficiency, and the pursuit of excellence without investing time and effort into building emotional connection between people.

Without making the time to understand oneself and others around you, the chances of building these connections reduce to almost zero and accelerate the chances of a toxic culture. The way to avoid this, is to dramatically increase the amount of empathy that exists between team members.

The ability to ‘feel into another person’ is a skill that everyone can learn. When we take an active interest in others and learn how to listen to understand, rather than to listen to understand, everything changes.

Without empathy connections are lost, communication breaks down, trust erodes and collaboration becomes impossible. However when done well it becomes the glue that holds the team together and generates the relationships required to achieve.

How much empathy exists in your team?

Subscribe to Colin on Culture Sign up with your email * indicates required Email Address *