Gerard Dion's Blog, page 7

May 1, 2017

Photos of Jean-Paul Sartre & Simone de Beauvoir Hanging with Che Guevara in Cuba (1960)

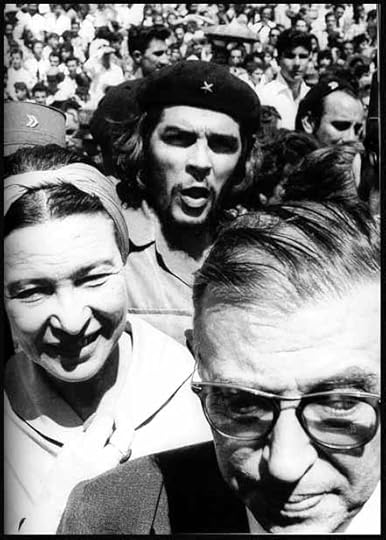

In 1960, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir ventured to Cuba during, as he wrote, the “honeymoon of the revolution.” Military strongman Fulgencio Batista’s regime had fallen to Fidel Castro’s guerilla army and the whole country was alight with revolutionary zeal. As Beauvoir wrote, “after Paris, the gaiety of the place exploded like a miracle under the blue sky.”

At the time, Sartre and de Beauvoir were internationally renown, the intellectual power couple of the 20th century. Beauvoir’s book, The Second Sex (1949), laid the groundwork for the feminism movement, and her book The Mandarins won France’s highest literary award in 1954. Sartre’s name had become a household word. The philosophy he championed – Existentialism – was being read and debated around the world. And his political activism — loudly condemning France’s war in Algeria, for instance — had given him real moral authority. When Sartre was arrested in 1968 for civil disobedience, Charles de Gaulle pardoned him, noting, “You don’t arrest Voltaire.” As Deirdre Bair notes in her biography of Beauvoir, “Sartre became the one intellectual whose presence and commentary emerging governments clamored for, as if he alone could validate their revolutions.” So it’s not terribly surprising that Fidel Castro wined and dined the two during their month in Cuba.

Cuban photographer Alberto Korda captured the couple as they met with Castro, and other leaders of the revolution. One picture (above) is of Guevara in his combat boots and trademark beret, lighting a cigar for the French philosopher. Sartre looks small and unhealthy compared to the strapping, magnetic revolutionary. Sartre was apparently impressed by the time he spent with the guerilla leader. When Che died in Bolivia seven years later, Sartre famously wrote that Guevara was “not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age.”

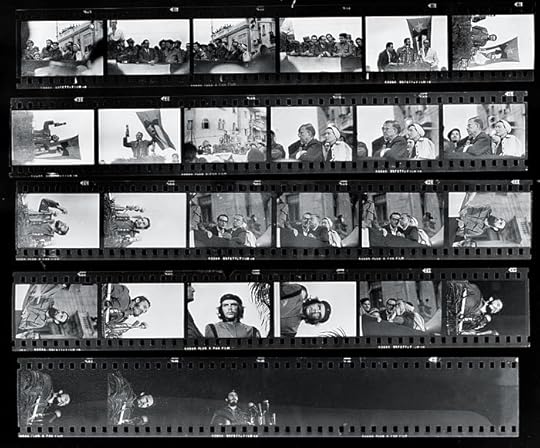

Later, Korda caught them as they were guided through the streets of Havana. And as you can see (below), that iconic image of Guevara, later plastered on T-shirts and Rage Against the Machine album covers, is on that same role of film.

When the couple returned to Paris, Sartre wrote article after article extolling the revolution. Beauvoir, who was equally impressed, wrote, “For the first time in our lives, we were witnessing happiness that had been attained by violence.”

Yet their enthusiasm for the regime cooled when they returned to Cuba a year later. The streets of Havana had little of the joy as the previous year. When they talked to factory workers, they heard little but parroting of the official party line. Beauvoir and Sartre ultimately denounced Castro (along with a bunch of other intellectual luminaries like Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Octavio Paz) in an open letter that criticized him for the arrest of Cuban poet Herberto Padillo.

Want to Improve Border Security? Seek Better Relations with Cuba

Ted Piccone, The National Interest Photo Credit: Huffington Post

As the Trump administration carries out its promised review of U.S. policy toward Cuba, it should think hard about the national and economic security implications of its next move. Three apparent courses of action—rolling back engagement and increasing punitive sanctions, continuing with normalization, or conditioning improved relations on further changes in Cuba—have distinct ramifications for the White House’s stated priorities to improve border security and generate jobs at home.

The chosen strategy will also influence to what extent rivals like China and Russia move further and faster to cement ties with Havana, at America’s expense. If this occurs, like-minded allies from Europe and Latin America could become preferred partners instead. Most importantly, Washington’s approach will directly affect the ability of Cuba’s eleven million citizens to fulfill their aspirations to live normal, prosperous and freer lives, in harmony with the two million Cubans living in the United States.

Cuban sugar burns to recapture sweet smell of success

Pedro Betancourt (Cuba) (AFP) – A sweet smell of treacle used to fill the air in the village of Pedro Betancourt — but like the workers from the derelict Cuba Libre sugar refinery, it has dispersed.

It was the smell of success against the odds for Cuba, reviled by the United States and its allies in the Cold War but still a world champion sugar producer — until the Soviet Union fell and stopped buying it from Fidel Castro’s communist regime.

Now a demolition crane is attacking what is left of the Cuba Libre refinery’s rusty steel skeleton. Fidel is dead, the Cold War is over — and Cuba wants its sugar industry back.

“The refinery was the life of the people who lived here,” says Arnaldo Herrera, 86. He lost his job at the plant when it closed in 2004.

“When that changes, life changes.”

– Cane on the risin’ –

Britain and other colonial powers grew fat on Cuban sugarcane — harvested by black slaves — from the 18th century until independence at the turn of the 20th.

The island then sold a lot of sugar to the United States until Washington imposed a trade embargo after communist revolutionary Castro took over in 1959.

Castro later announced a “revolutionary offensive” to relaunch the industry. The Soviet Union bought the sugar at preferential prices.

For 1970 Castro famously set a production target of a “great harvest” of 10 million tonnes. (He fell short by 1.5 million.)

But after the Soviet bloc collapsed in 1989, with the US embargo still in place and prices falling, the island could no longer compete.

Two-thirds of its refineries — about 100 plants — have shut down since 2002.

From eight million tonnes a year in the 1990s, production plunged to just over one million in 2010.

“That was when we touched bottom,” says Rafael Suarez, head of international relations for the state sugar monopoly Azcuba.

“Since then an effort has been made. The refineries have been improved and a lot of emphasis has been put on recovering sugarcane production.”

Suarez says Azcuba is also looking to expand production of sugar derivatives: rum, cattle feed and renewable fuel.

– Human cost –

Some 100,000 Cubans used to work in refineries like the one in Pedro Betancourt in the east.

The refineries used to pay well, for Cuba — at least double the $28 average monthly salary.

Julio Dominguez, 84, worked in Cuba Libre until it shut.

“This town has been stripped bare. Tobacco production is all it has left,” he says.

The refinery stopped milling in 2004 and demolition began in 2007. Like everything in Cuba, it takes time.

Some still weep when they pass the site, says the head of the demolition, Eliecer Rodriguez.

“I am knocking it down, but that was someone else’s decision,” he says.

Workers were kept on their salaries for some time after the closure.

Some have since moved on to work as tobacco producers, taxi drivers or handymen. Others have emigrated to the United States.

Soccer beginning to gain foothold in Cuba

(Photo: Ezra Shaw, Getty Images)

663CONNECTTWEET 1LINKEDINCOMMENTEMAILMORE

HAVANA — Aerial photographs of soccer fields in Cuba were once enough to sound the alarm.

“Cubans play baseball,” warned a CIA consultant in 1970 after studying U.S. satellite images. “Russians play soccer.”

That was then on the island, soccer is now. Parks, empty lots and alleyways that were once home to baseball in and around Havana have been taken over by pickup or organized soccer games. Baseball aficionados say the shift began a decade ago and could have a major effect on a nation that has seen its top baseball talent defect — often under perilous conditions — to sign lucrative contracts with Major League Baseball teams.

“I’d been told it was happening, but until you see it with your own eyes, you can’t believe it,” says Milton Jamail, the author of Full Count: Inside Cuban Baseball, who has been to the island 10 times, most recently in January. “You always hear that baseball is Cuba’s game. But it is clearly not the only sport that has captured the attention of young men on the island.”

Reasons for this sports shift might sound familiar to U.S. fans:

•Baseball moves too slowly, especially on television.

•Soccer only requires a ball, while baseball equipment can be too expensive.

•Baseball in Cuba is often viewed as the sport of the older generation.

Perhaps as a sign of the times, Team Cuba failed to get out of pool play in the World Baseball Classic. Netherlands eliminated Cuba 14-1 on March 15.

Despite such struggles, they have been playing baseball in Cuba for almost as long as it’s been in the USA. In 1864, Nemesio Guillo returned to his homeland with a bat and baseball after studying in the USA. He and his brother, Ernesto, founded the Habana Base Ball Club, and the game in Cuba soon flourished. The first ballpark in the country was built in 1874 in Matanzas, east of Havana, and amateur leagues were soon organized around the island’s sugar mills.

In the USA, baseball remains as traditional as it gets. In Cuba, though, playing the game could be viewed as a political statement. In the 1890s, students and would-be revolutionaries were attracted to the sport because it demonstrated their support for an independent Cuba. Soon after taking power in 1959, Fidel Castro barnstormed with his ballclub, Los Barbudos. Yet turn on a TV in a Cuban home, and it’s easier to find soccer than baseball.

“Barcelona, Real Madrid, games from Brazil — those are all available to Cubans now,” says Luke Salas, a Cuban-American former minor league ballplayer who attempted to play in a provincial league outside of Havana in 2012. “And when you think about the growth of soccer on the island, it makes sense.”

Norwegian Cruise Line announces 33 Miami-to-Cuba trips for 2018 cruise season

Emon Reiser, South Florida Business Journal

Norwegian Cruise Line on Tuesday announced that it will expand its Cuba cruising offerings in 2018 with 33 sailings. Most of the trips will have overnight calls in Havana.

Norwegian, owned by Miami-based Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings Ltd. (Nasdaq: NCLH), will begin hosting the four-day roundtrips from PortMiami at the start of the 2018 cruise season March 26, 2018 on the Norwegian Sky. The newly announced trips are in addition to the 30 calls Norwegian will offer through December 2017.

The sun rises over the famous Malecon in Havana, Cuba.

JOCK FISTICK

“Cuba is a spectacular destination and we are seeing incredible demand from our guests to experience the beautiful and cultural-rich city of Havana and her warm and friendly people,” said Andy Stuart, president and CEO of Norwegian Cruise Line. “We are excited to provide even more opportunities for our guests to experience this incredible destination into 2018.”

Cruisers can travel to Cuba on Norwegian’s ships as cultural visitors instead of tourists because the U.S. embargo against the country still prevents American tourism to the island. The cruise line offers 15 half and full-day Office of Foreign Assets Control-compliant shore excursions. Sales for the cruises open April 20.

Norwegian is adding trips to Cuba as airlines are dropping their routes between South Florida and the island nation. Fort Lauderdale-based Silver Airways will drop its flights to Cuba because the airline said there’s not enough demand.Denver-based Frontier Airlines will do the same.

Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings operates Norwegian Cruise Line, Oceania Cruises and Regent Seven Seas Cruises brands. It has a combined fleet of 24 ships in operation and another eight ships sailing by 2025.

Trump administration continues to issue OFAC licenses authorizing business with Cuba

CUBA

APRIL 04, 2017 6:38 AM

APRIL 04, 2017 6:38 AM

BY NORA GÁMEZ TORRES

ngameztorres@elnuevoherald.com

Although the Trump administration’s Cuba policy review has not been completed, a U.S.-based broadcast and video facilities company has received a license to operate on the island and to contract with a Cuban state enterprise.

The license granted to Cuba International Network by the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control allows the company to contract with Cuban government-operated radio and television enterprise known by the Spanish acronym RTV and authorizes all transactions to provide U.S. and international customers with recording equipment and trained Cuban staff.

“As a broadcaster, we have been closely watching current changes in Cuba and if there is going to be a market. The companies we work with, all wanted to go to Cuba to produce products,” the founder and CEO of CIN, Barry H. Pasternak, told el Nuevo Herald. Currently, the company offers “from a one-camera commercial shoot up to virtually any event,” through collaborations with major producers such as Gearhouse Broadcast and PRG.

The company, with offices in Miami, obtained the license on March 20, after waiting more than a year in a process that began in December 2015 under the administration of former President Barack Obama. The company is authorized to shoot on the island but is still waiting for Cuban government permits to have its own facility on the island.

Pasternak said he did not know why the process had taken so long but that he was “happy to see that the government feels that we are trying to benefit the United States. We are Americans. We want to support an industry that has never filmed in Cuba, an untouched country, and many people want to see the country.”

He also stressed that his company has no political motivations.

OUR JOB IS TO MAKE MOVIES, TO PRODUCE QUALITY CONTENT. WE ARE NOT A POLITICAL COMPANY.

Barry Pasternak, Cuba International Network

“We did not put up the wall; the embargo is out of our area. Our job is to make movies, to produce quality content. We are not a political company,” said Pasternak, who has more than 35 years of experience in broadcasting in the Caribbean region. CIN is a project dating back to 1992.

“It was hard but we love what we do and we want to do it in a beautiful location,” said the producer, who was previously involved in a telemedicine project involving an American university, the government of Cuba and other Caribbean countries.

According to John Kavulich, the president of the U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council and who reported on CIN’s license, this was not the first license issued by OFAC since President Donald Trump took office in January. OFAC did not immediately respond to questions sent by el Nuevo Herald.

Kavulich also said that there are companies that received licenses in the final months of the Obama administration and have not yet gone public for fear of “becoming target for the Trump administration and/or becoming the catalyst for policy and regulatory changes by the Trump administration.”

During his campaign, Trump promised to renegotiate Obama’s opening to Cuba or cancel the agreements if the Cuban government does not offer concessions. The White House then announced a full policy review that has not yet ended, according to a spokeswoman.

During the so-called “thaw” under the Obama administration, several Hollywood and U.S. television networks flew to Cuba to film for the first time in nearly half a century. Among the shoots were for “Fast and Furious 8”, “House of Lies” and “Conan”. But the shortage of technology on the island has increased the costs of these productions. The Rolling Stones — who staged a massive concert in Havana — and the team of “Fast and Furious” had to transport all audio and film equipment they needed to the island.

CIN said it would fill that gap.

The company plans to shoot a classic-car rally and broadcast a live jazz concert to American audiences later this year. Pasternak said he has not seen changes in the interest of U.S. companies for filming on the island, a virtually untapped market, although, he said, “I see people being concerned about the [current] administration.”

Follow Nora Gámez Torres: @ngameztorres

Sun, sand and socialism ….What the tourist industry reveals about Cuba

Print edition | The Americas

Apr 1st 2017| HAVANA

TOURISTS whizz along the Malecón, Havana’s grand seaside boulevard, in bright-red open-topped 1950s cars. Their selfie sticks wobble as they try to film themselves. They move fast, for there are no traffic jams. Cars are costly in Cuba ($50,000 for a low-range Chinese import) and most people are poor (a typical state employee makes $25 a month). So hardly anyone can afford wheels, except the tourists who hire them. And there are far fewer tourists than there ought to be.

Few places are as naturally alluring as Cuba. The island is bathed in sunlight and lapped by warm blue waters. The people are friendly; the rum is light and crisp; the music is a delicious blend of African and Latin rhythms. And the biggest pool of free-spending holidaymakers in the western hemisphere is just a hop away. As Lucky Luciano, an American gangster, observed in 1946, “The water was just as pretty as the Bay of Naples, but it was only 90 miles from the United States.”

There is just one problem today: Cuba is a communist dictatorship in a time warp. For some, that lends it a rebellious allure. They talk of seeing old Havana before its charm is “spoiled” by visible signs of prosperity, such as Nike and Starbucks. But for other tourists, Cuba’s revolutionary economy is a drag. The big hotels, majority-owned by the state and often managed by companies controlled by the army, charge five-star prices for mediocre service. Showers are unreliable. Wi-Fi is atrocious. Lifts and rooms are ill-maintained.

Despite this, the number of visitors from the United States has jumped since Barack Obama restored diplomatic ties in 2015. So many airlines started flying to Havana that supply outstripped demand; this year some have cut back. Overall, arrivals have soared since the 1990s, when Fidel Castro, faced with the loss of subsidies from the Soviet Union, decided to spruce up some beach resorts for foreigners (see chart). But Cuba still earns less than half as many tourist dollars as the Dominican Republic, a similar-sized but less famous tropical neighbour.

With better policies, Cuba could attract three times as many tourists by 2030, estimates the Brookings Institution, a think-tank. That would generate $10bn a year in foreign exchange, twice as much as the island earns now from merchandise exports. Given its colossal budget deficit, expected to hit 12% of GDP this year, that would come in handy. Whether it will happen depends on two embargoes: the one the United States imposes on Cuba and the one the Castro regime (now under Fidel’s brother, Raúl) imposes on its own people.

The United States embargo is a nuisance. American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, and Americans are not technically allowed to visit the island as tourists. (They have to pretend they are going for a family visit or a “people-to-people exchange”.) Mr Obama allowed American hotel chains to dip a toe into Cuba; one, Starwood, has signed an agreement to manage three state-owned properties.

Pearl of the Antilles, meet swine

But investment in new rooms has been slow. Cuba is cash-strapped, and foreign hotel bosses are reluctant to risk big bucks because they have no idea whether Donald Trump will try to tighten the embargo, lift it or do nothing. On the one hand, he is a protectionist, so few Cubans are optimistic about his intentions. On the other, pre-revolutionary Havana was a playground where American casino moguls hobnobbed with celebrities in raunchy nightclubs. Making Cuba glitzy again might appeal to the former casino mogul in the White House.

The other embargo is the many ways in which the Cuban state shackles entrepreneurs. The owner of a small private hotel complains of an inspector who told him to cut his sign in half because it was too big. He can’t get good furniture and fixtures in Cuba, and is not allowed to import them because imports are a state monopoly. So he makes creative use of rules that allow families who say they are returning from abroad to repatriate their personal effects (he has a lot of expat friends). “We try to fly low under the radar, and make money without making noise,” he sighs.

Cubans with spare cash (typically those who have relatives in Miami or do business with tourists) are rushing to revamp rooms and rent them out. But no one is allowed to own more than two properties, so ambitious hoteliers register extra ones in the names of relatives. This works only if there is trust. “One of my places is in my sister-in-law’s name,” says a speculator. “I’m worried about that one.”

Taxes are confiscatory. Turnover above $2,000 a year is taxed at 50%, with only some expenses deductible. A beer sold at a 100% markup therefore yields no profit. Almost no one can afford to follow the letter of the law. For many entrepreneurs, “the effective tax burden is very much a function of the veracity of their reporting of revenues,” observes Brookings, tactfully.

The currency system is, to use a technical term, bonkers. One American dollar is worth one convertible peso (CUC), which is worth 24 ordinary pesos (CUP). But in transactions involving the government, the two kinds of peso are often valued equally. Government accounts are therefore nonsensical. A few officials with access to ultra-cheap hard currency make a killing. Inefficient state firms appear to be profitable when they are not. Local workers are stiffed. Foreign firms pay an employment agency, in CUC, for the services of Cuban staff. Those workers are then paid in CUP at one to one. That is, the agency and the government take 95% of their wages. Fortunately, tourists tip in cash.

The government says it wants to promote small private businesses. The number of Cubans registered as self-employed has jumped from 144,000 in 2009 to 535,000 in 2016. Legally, all must fit into one of 201 official categories. Doctors and lawyers who offer private services do so illegally, just like hustlers selling black-market lobsters or potatoes. The largest private venture is also illicit (but tolerated): an estimated 40,000 people copy and distribute flash drives containing El Paquete, a weekly collection of films, television shows, software updates and video games pirated from the outside world. Others operate in a grey zone. One entrepreneur says she has a licence as a messenger but wants to deliver vegetables ordered online. “Is that legal?” she asks. “I don’t know.”

Cubans doubt that there will be any big reforms before February 2018, when Raúl Castro, who is 86, is expected to hand over power to Miguel Díaz-Canel, his much younger vice-president. Mr Díaz-Canel is said to favour better internet access and a bit more openness. But the kind of economic reform that Cuba needs would hurt a lot of people, both the powerful and ordinary folk. Suddenly scrapping the artificial exchange rate, for example, would make 60-70% of state-owned firms go bust, destroying 2m jobs, estimates Juan Triana, an economist. Politically, that is almost impossible. Yet without accurate price signals, Cuba cannot allocate resources efficiently. And unless the country reduces the obstacles to private investment in hotels, services and supply chains, it will struggle to provide tourists with the value for money that will keep them coming back. Unlike Cubans, they have a lot of choices.

The first U.N. human rights special rapporteur to visit Cuba in 10 years arrives in Havana on Monday

The first U.N. human rights special rapporteur to visit Cuba in 10 years arrives in Havana on Monday. Maria Grazia Giammarinaro, an Italian judge, also will visit Matanzas and Artemisa. Desmond Boylan AP

Cuba will open up to a U.N. human rights expert for first time in a decade

The first independent United Nations human rights expert to visit Cuba in a decade will travel to the island next week.

U.N. Special Rapporteur Maria Grazia Giammarinaro, a member of the United Nation’s Human Rights Council and special rapporteur on trafficking in persons, with an emphasis on women and children, will arrive in Cuba on Monday and stay for five days, the United Nations said in a statement from Geneva on Wednesday.

Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Relations confirmed the upcoming visit Thursday and said Giammarinaro was making the trip at the invitation of the Cuban government.

“Aware that human trafficking violates the human rights of the victims, the Cuban government has maintained a zero tolerance policy for this crime,” the Cuban Embassy at the U.N. office in Geneva said.

“My visit is an opportunity to meet relevant authorities and key people and groups, to determine the progress made and the challenges Cuba faces in addressing trafficking for sexual and labor exploitation, as well as any other forms of trafficking,” Giammarinaro said. “Particular attention will be paid to measures in place and those planned to prevent trafficking, to protect victims and provide them with access to effective remedies.”

During her trip to Havana, Matanzas and Artemisa, Giammarinaro will meet with members of civil society organizations fighting against people-trafficking as well as government officials.

She is expected to present her preliminary findings at a news conference at Havana’s International Press Center on April 14, and her recommendations will be included in an official report to be presented to the U.N. Human Rights Council in June 2018.

Currently a judge of the Civil Court of Rome, Giammarinaro was appointed as Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children, by the Human Rights Council in June 2014. She works on a voluntary basis and is not a member of the U.N. staff.

Giammarinaro has a long history in combating human trafficking, and drafted the European Union directive on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims.

“Over the past year my mandate has focused on the link between trafficking in persons and conflict and particularly has looked at the vulnerabilities of persons fleeing conflict to become trafficked, especially refugees and asylum seekers,” Giammarinaro said during a speech in March.

Combating human trafficking was one of the dialogues begun between the United States and Cuba under the Obama administration’s rapprochement with Havana.

The last U.N. human rights expert to visit Cuba was the special rapporteur on the right to food.

February 27, 2017

Meet the Entrepreneurs Breaking Into This Long-Forbidden Market | Inc.com

Meet the Entrepreneurs Breaking Into This Long-Forbidden Market | Inc.com

“A whole litany of countries are in Cuba doing business, investing hundreds of millions of dollars. This idea that it’s not happening? It’s happening, but without us.” –Darius Anderson, founder of U.S. Cava Exports, a Napa Valley-based company hoping to sell California wines to Cubans.

CREDIT: Edel Rodriguez

The Friday before Halloween, Josh Weinstein was set to take his first trip to Cuba: bags packed, visa in hand, leased Beechcraft turbo-prop booked for Sunday pickup at Sarasota Bradenton International. Then the dispatcher called. We have verbal approval to fly to Havana, he told Weinstein, but we’re still waiting on one last stamp from the Cuban government. Don’t worry, he explained, this happens all the time. Unfortunately, the government offices were now closed for the weekend. “We’ll keep pushing,” he promised.

Weinstein is president of Witzco Challenger, a $12 million family business that builds heavy-haul trailers in Sarasota, Florida, and ships them all over the world. Witzco lost about half its sales in ’08 and ’09 during the Great Recession. That was not long after Weinstein, former treasurer of his local stagehands union and grandson of Witzco’s founder, took over the company from his aunt and uncle, and he’s been scrambling to recover ever since. Exports are a big part of his business, about 35 percent, but they’ve been slipping lately. The stronger dollar hasn’t helped.

His unlikely solution: Cuba. The forbidden market less than an hour’s direct flight from Witzco’s central Florida factory is suddenly bursting with pent-up demand. Tourism in Cuba is soaring, on pace to exceed 2015’s record 3.5 million visitors, including a growing number of Americans who find a way to qualify for one of 12 exceptions to the Treasury Department’s limits on travel. (U.S. tourism is technically still banned.) Weinstein’s betting on a construction boom, spurred by the Cuban government’s plan to double the number of hotel rooms in the country by 2020, in pursuit of economic growth. “The first thing they’re going to have to do is infrastructure,” Weinstein says excitedly. “Water, septic, cable, electricity, communications. They’re going to need heavy equipment. My trailer moves the heavy equipment.” Not exactly a Cuba expert, Weinstein wants to see for himself. “I don’t really know the market, only what I’ve been able to Google,” he says. So he booked a booth at Cuba’s international trade show, slated for the fall.

Sunday night, the stamp came through. Monday morning, he was on his way, a day later than hoped. (The first lesson anyone learns when dealing with Cuba: It’ll happen when it happens.) Forty-five minutes across the Everglades to Miami to top off the tank–gas is much cheaper in the U.S.–and then another 45 minutes across the Straits of Florida to Havana. Upon landing at José Martí International Airport, Weinstein and his posse of two–all wearing khakis and Witzco golf shirts–were met in an otherwise deserted terminal by unsmiling customs officials, who opened one of Weinstein’s bags. In it was a stash of trade-show paraphernalia–candy, logoed pens, and sales pamphlets in Spanish, English, and Russian (in case there were any Russians left in Cuba, Weinstein figured). The pamphlets raised eyebrows. Propaganda, declared one of the officials. Where is your approval? A discussion ensued. Weinstein turned on his charm. Maybe a little bit of money changed hands. “It’s the cost of doing business,” Weinstein says. “I’m OK with it.”

And the Witzco delegation was in.

Josh Weinstein, the third-generation president of Witzco Challenger, a Sarasota, Florida-based company hit by the Great Recession, is hoping to rebound by riding the anticipated tourism boom in Cuba.

CREDIT: Lisette Poole

When President Obama flew to Havana last March, it marked the first visit to Cuba by a sitting American president since Calvin Coolidge in 1928. His posse numbered more than 1,000. Among them: Brian Chesky, founder of Airbnb, Dan Schulman, CEO of PayPal, and Fubu founder and Shark Tank judge Daymond John. The president drove straight to the Meliá Habana Hotel, where he addressed the staff of what used to be the United States Interests Section of the Embassy of Switzerland in Havana (it’s a long story) but is now a full-fledged U.S. embassy. There he spoke of his desire to “forge new agreements and commercial deals” with Cuba, in line with the main thrust of U.S. policy as of December 2014, when the current wave of reforms began.

A lot’s happened since then, including the death of Fidel Castro; the removal of Cuba from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism; the restoration of full diplomatic relations; the resumption of regularly scheduled flights by U.S. airlines, including American, Delta, United, and JetBlue; authorization for U.S. hoteliers Marriott and Starwood to pursue Cuba deals; service agreements involving U.S. cell-phone providers; and glory, hallelujah, the granting of permission for American visitors to bring home Cuban rum and cigars.

But that doesn’t mean Cuba is open for business. There’s still the nettlesome matter of the embargo–a dense web of constraints, restrictions, and outright prohibitions, some in place since 1960, that, despite the recent thaw, prevents anything approaching normal business relations. Most commerce between the United States and Cuba is banned outright. Everything else is a hassle. For instance, while U.S. companies have been permitted to sell food and medicine to Cuba since the Clinton administration, the U.S. government often requires Cuban customers to pay the full amount up front. (That, in a nutshell, is why Cuba buys nearly all its rice from Vietnam, rather than from nearby U.S. growers.) And if you’re an American trying to do anything in Cuba, you had better bring plenty of cash, which is all anyone accepts. Unless you happen to have a credit or debit card from Stonegate Bank–a Fort Lauderdale, Florida, institution that has a temporary continental American monopoly on Cuba-ready cards–plastic credit is worthless, and ATMs barely exist.

The embargo is like an argument that’s been going on for so long, nobody remembers anymore how or why it started. Initially, under President Eisenhower, it banned only sugar imports. After Cuba responded by confiscating the assets of U.S. companies, it was broadened to cover nearly all trade between the nations. Soon it morphed into a Cold War weapon to punish Castro for aligning with the Soviet Union, and supporting communist-led insurgencies in Nicaragua and Angola. Cuba’s dismal record on human rights didn’t help.

But attitudes toward the embargo have changed. In a CBS News/New York Times poll conducted on the eve of Obama’s Cuba visit, more than half of Americans (55 percent) said they supported doing away with it. A more recent Florida International University poll of Cuban Americans living in Miami-Dade County–traditionally ground zero for the no-compromise camp–found an even bigger majority who would be happy at this point to move on. But we’re still stuck.

Washington, D.C., attorney Robert Muse has been advising U.S. companies on Cuba for 25 years. He says that lifting the embargo is up to the United States. He equates Cuba’s position to that of an abused wife whose husband says he’ll stop beating her if she’ll start putting dinner on the table: “Her attitude, quite rightly, is, ‘It’s you attacking me! You have to stop. Then we can have normal relations.’ ”

If and when the embargo is lifted, American companies need to remember what kind of market they’re dealing with. Cuba indeed dominates the Caribbean, by landmass (it’s roughly the size of Virginia) and by population (11.3 million). But it’s poor. The average state salary is $25 a month. In 2010, according to the CIA’s latest estimate, its gross domestic product per capita was $10,200, one rung up on the world ladder from Swaziland’s. That’s partly why John Kavulich, longtime head of the U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, sees “a lot of inspiration and aspiration chasing very little reality” in Cuba. Americans assume, not unreasonably, that Cubans “need everything, they want everything, and they put a period there,” Kavulich says. “But there’s a next sentence: Do they have the resources to purchase everything? Dubai isn’t 93 miles south of Florida. Cuba is.”

Even so, Weinstein and other eager Americans are stubbornly optimistic. Entrepreneurs like Saul Berenthal, for instance, a 72-year-old in Raleigh, North Carolina, who wants to sell small tractors to Cuban farmers. And Darius Anderson, a political consultant, lobbyist, and investor who’s been visiting Cuba since he was a college student, and now has a scheme to sell California wines to Cuban restaurateurs. Everybody wants to believe that we’re at the beginning of the end of an era; that no one–not unforgetting Cuban émigrés in Miami, not Fidel’s ghost, not a brash and unpredictable President Trump–can halt the momentum now. That the embargo must be, will be, swept aside, and the rivers of commerce will flow.

But Cuba is not for innocents or neophytes. “People get besotted with Cuba,” Muse warns. “If you’re a little guy, you might think that because the big guys aren’t there, you can play in those waters. It’s exotic. You’re a pioneer! All these things combine to make some people abandon basic business principles.”

“People get besotted with Cuba. If you’re a little guy, you might think that because the big guys aren’t there, you can play in those waters. It’s exotic. You’re a pioneer! All these things combine to make some people abandon basic business principles.” –Robert Muse, an attorney who advises U.S. companies on Cuba

The fairground for Cuba’s international trade show is 12 miles south of central Havana. It’s a slow cab ride, on crowded roads filled with midcentury Fords, Chevys, and Cadillacs, many of them refitted with diesel motors, not one of which would pass a U.S. emissions inspection. A mural of Che Guevara hovers omnisciently over the Plaza de la Revolución, while billboards flaunt slogans like socialismo o muerte (“Socialism or Death”) and normalizar no es sinónimo de bloquear (“Normalization and Blockades Don’t Go Together”), a blunt reminder of Cuba’s all-or-nothing stance on the embargo, which Cubans call “the blockade.”

The American pavilion is a hike from the trade show’s main entrance, in the farthest corner of the grounds, beyond the scattered remnants of past exhibitions–a petrified pump jack, a stilled windmill, a parked Air Cubana airliner repurposed as a restaurant. JetBlue banners flank the entrance. Inside, ordinary Cubans who have managed to snag coveted trade show credentials graze the American booths, scooping up free hats, pens, and pistachios. Perhaps because there is no conventional advertising in Cuba (it’s illegal), Cuban consumers are adept at ferreting out whatever’s available, wherever it can be found.

The National Auto Parts Association has a booth, looking toward the day when it can begin populating Cuba with its stores. So do a smattering of state-sponsored trade delegations representing poultry farmers, soybean growers, and the Port of Virginia; and all manner of small and midsize U.S. manufacturers, displaying motors, electronic controls, and other industrial gear, none of which are yet on the list of permissible products. The U.S. embassy’s chargé d’affaires, Jeffrey DeLaurentis, roams the aisles in a seersucker suit, chatting up exhibitors and awkwardly ducking reporters. (“There is still an embargo,” his aide explains apologetically.)

Saul Berenthal, a Cuban emigre based in Raleigh, North Carolina, was supposed to be the first American entrepreneur to build a factory in Cuba–until his company got caught in political crossfire.

CREDIT: Lisette Poole

Overall, attendance by American exhibitors is lower this year than last, when Obama’s first round of reforms created a kind of euphoria that has since dissipated. Those who have returned see the potential but understand the need for patience. Among them is investor Noel Thompson, decked out in a blue blazer advertising his ties to the U.S. Olympic Committee. Thompson is a former Goldman Sachs banker now running his own hedge fund in New York City. He’s been coming down to Cuba every few months for the past couple of years, working his way into the culture, gathering intel, developing contacts. He imagines doing a lot of business in Cuba one day–trading currencies, advising on deals, helping privatize government assets, and otherwise capitalizing on the explosion he thinks will surely come when the embargo lifts and America fully engages with Cuba’s suppressed capitalist passions. It won’t happen tomorrow, he knows, or even next year, but one day. “Maybe it’s my Goldman training,” Thompson says. “When you see a butterfly flap its wings … ”

Manning a nearby booth with sunglasses propped on his forehead and an unlit cigar clenched in his teeth, another American, Darius Anderson, presides over a winetasting led by his pal Fernando Fernández, Cuba’s preeminent blender of rums and cigars. Anderson first visited Cuba in 1986 as a student at George Washington University, where he had a poster of Che Guevara on his dorm room wall. When his pals went to Florida for spring break, he went north to Toronto, from which he was able to get to Havana. His total visits since then: “Somewhere in the mid-60s,” he guesses. Every time the border agents run his passport, they ask, “Why so many times?”

Originally, he went because it was forbidden, Anderson says, and now it’s because he’s long since fallen in love with “all things Cuban: the music, the culture, the cigars, the baseball.” After college, Anderson worked for a Democratic congressman on Capitol Hill, was an advance man for Bill Clinton in California, and apprenticed seven years at the right hand of supermarket billionaire Ron Burkle–a useful résumé for navigating a market in which business and politics are inseparable.

With his company U.S. Cava Exports, Anderson, 47, is trying to bring expensive wines from Napa Valley to Cuban consumers. He’s been laying the groundwork for years, hosting a seven-day tour of Napa and Sonoma wineries for his Cuban friends, and leading a party of more than 100 California vintners on an educational mission to Cuba, where they met with chefs and sommeliers. Like Weinstein, Anderson is hoping to make money on tourism. Unlike Weinstein, he’s peddling an embargo-exempt agricultural product that’s not contingent on new construction. This should be easy.

And yet, 2,500 miles northwest of Havana, in a refrigerated warehouse near Napa County Airport, sits a shipping container filled with Anderson’s stranded inventory: 1,200 cases of carefully curated California sauvignon blanc, zinfandel, pinot noir, cabernet, and chardonnay. Total value, just under $400,000. It’s been there all fall, costing him at least $500 per month, and not for want of a buyer. In fact, Anderson has one all lined up, a Cuban state-owned distributor willing to pay full price in advance, per U.S. law. But there’s a holdup. Anderson is waiting on final approval from the highest levels of government–in this case, Cuba’s foreign ministry.

U.S. Cava Exports is only one of Anderson’s ventures at the moment, so he has the luxury to wait this bureaucratic purgatory out. He still sees a chance to have “a real, viable business and grow it over time.” The rest of the world is already here, he points out. Not just Cuba’s biggest trading partner, China, and Spain–its oldest–but also Brazil, Canada, Mexico, the Netherlands. The list goes on. “A whole litany of countries are here doing business,” Anderson says. “They trust the system well enough to invest hundreds of millions of dollars. This idea that it’s not happening? It’s happening, but it’s happening without us.”

At least twice since the late ’90s, emissaries associated with Trump companies have visited Cuba to scope out investment opportunities for hotels and golf courses–acts that may well have violated the embargo.

Saul Berenthal went to high school before the revolution. He was born in Havana, where his parents met after fleeing the Nazis in Eastern Europe. His father worked his way from Holocaust refugee to sole GM parts supplier for Cuba, which helped land Saul at the elite Havana Military Academy. In 1960, his parents sent their 16-year-old son to study in the United States. They visited him the following year, expecting to stay for a few months. Then came the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Suddenly, they were unwilling to return to Cuba, refugees once again, this time in America.

Bespectacled and trim, still at home in a loose-fitting guayabera, Berenthal has a complicated relationship with his birthplace. He belongs solidly to the generation of exiles whose grim resolve and political clout have defined U.S. aggression toward Cuba. But he’s also become a full-fledged American, having had spent 18 years at IBM, where he met Horace Clemmons, his future business partner. They bonded over their frustration with IBM’s stubborn attachment to proprietary product lines when the future was all about open-source computing. “We worked hard, lived the American dream, created three companies and sold them, and set ourselves up for a nice retirement,” says Berenthal.

But, a couple of years into retirement, Cuba beckoned, and starting in 2007, Berenthal was finding excuses to visit his birthplace. “It was curiosity more than anything,” he says. The surprise was that he felt instantly at home. The language, the mannerisms, the customs, the operating in a culture where it’s hard to make appointments (“You’ll be here next week? Look me up”) and a meeting might not happen because somebody’s car won’t start or he can’t find gas. Where checking email on the fly means locating a Wi-Fi hotspot and making sure you’ve got enough minutes left on your government-issued access card. “Not very well organized, but I understand why,” says Berenthal, revealing a trace of his native Spanish. “People take care of things as they come up. They don’t know where they’ll be at any time until it’s that time.”

Berenthal still knew people who knew people in Havana. He was introduced to professors in the economics department at the University of Havana, organized academic exchanges, and got involved in studies that led to Cuba’s accelerated reengagement with the global economy in 2011. But it was Obama’s dramatic announcement on December 17, 2014–“Today, the United States of America is changing its relationship with the people of Cuba”–and the policy changes that followed that convinced Berenthal it was time to reunite with his old partner, Clemmons, and come up with a business idea for Cuba.

Berenthal knew that an American company could succeed in Cuba only if it was sensitive to the socialist country’s motivations for doing business with outsiders. Cuba is not interested in inviting foreign companies in to make a few players wealthy. If Cuba is to embrace capitalism, it will be on socialist terms: to generate revenue and become less dependent on imports, and so protect what Cubans consider the lasting achievements of the revolution–free education, free medicine, subsidized housing, and subsidized food.

U.S. entrepreneurs are beginning to visit Havana in anticipation of trade restrictions being lifted.

CREDIT: Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum Photos

Clemmons, a farm boy from Alabama, thought of tractors. Inexpensive tractors designed to meet the needs of small farmers in a poor country that’s rich in arable land but where many still work the land barefoot, behind a mule or an ox, without basic equipment. An alternative to a company like John Deere, which could come into Cuba with an expensive, proprietary product. Instead, Cleber, as their company is called, would assemble tractors according to open-source manufacturing principles, using standard components, making them easy to maintain and infinitely customizable. By creating an opportunity for Cubans to build an ecosystem of products around Cleber’s tractor, they would help kick-start the creation of a homegrown agricultural manufacturing industry.

Berenthal and Clemmons proposed building their tractor factory in Mariel, a planned economic development zone about an hour west of Havana. When Cuban officials expressed support, the pair began working to persuade their own government to create an opening in the embargo that would allow them to proceed. “We spent a lot of time in the Office of Foreign Assets Control and the Department of Commerce, trying to get it through,” says Berenthal. In February 2016, after months of meetings, they succeeded. Cleber won U.S. approval to build the first American-owned factory on Cuban soil since the revolution. It was a happy story, shot through with hopeful symbolism, coinciding perfectly with the Obama administration’s initiatives. They even got a shout-out in a White House press briefing.

But they still needed final approval from Cuba, and by last summer, Berenthal didn’t like the signals being sent from officials at Mariel: pushback on environmental standards and workplace safety, and worrisome doubts about whether Cleber fit with the development site’s larger goal of promoting high-tech manufacturing. Berenthal was baffled. None of the other projects in the Mariel pipeline–cigarettes, cosmetics, meatpacking, none of them U.S. backed–were obvious ways to achieve that goal. Here he was, trying to persuade higher-ups who opposed a simple, practical idea that somehow threatened them. He had flashbacks to his time at IBM. “Everybody is acting in their own best interests,” says Berenthal. “IBM wanted to protect the proprietary lab where they were building the proprietary technology and not accept change, because that would mean loss of power or prestige or even their jobs.”

In late October, Berenthal drove to Mariel for a meeting with development zone officials. “They were very cordial,” Berenthal says. Then they proceeded to tell him that after much consideration, they had decided not to approve Cleber’s proposal after all.

If Cuba is to embrace capitalism, it will be on socialist terms–to protect what Cubans consider the lasting achievements of the revolution.

Weinstein had a good trade show. He didn’t arrive until late on the first day–after the delay at customs, and an errant cab ride to the wrong fairground–but he hit the ground running. Within an hour, every bottled-water peddler in the building had a Witzco bumper sticker on his cooler, and most were wearing Witzco baseball caps. He made no actual sales to actual Cubans, of course. The embargo forbade him, which he knew going in. But he met a lot of people there, and went home happy at the end of the week with a long list of proposals to prepare for buyers from Canada, Panama, Mexico, Belgium, and Spain.

Then history happened. Days after the trade show ended, Donald Trump was unexpectedly elected president. Then Fidel Castro died. Suddenly American entrepreneurs with dreams of doing business in Cuba were forced to reevaluate everything.

When it comes to Cuba, Trump the politician appears to have a different mind than Trump the entrepreneur. At least twice since the late ’90s, emissaries associated with Trump companies have visited Cuba to scope out investment opportunities for hotels and golf courses–acts that may well have violated the embargo. Since the election, however, Trump’s been all bluster and ill will. When the news broke of the former dictator’s passing, he tweeted gleefully: “Fidel Castro is dead!” He soon followed up with, “If Cuba is unwilling to make a better deal for the Cuban people, the Cuban/American people and the U.S. as a whole, I will terminate deal.”

CREDIT: Edel Rodriguez

In reality, Trump’s tough talk is off base. As attorney Muse points out, there is no Obama-era “deal” between the nations. Only a “series of rolling measures” issued from various realms of the federal government that would be next to impossible to untangle one by one, and which few Americans object to anyway. But what Trump could do, says Muse, is “go big and go unilateral,” in a way that plays to his strength. That is, he could leapfrog Obama’s measured steps toward normalization by announcing his willingness to negotiate America’s $1.9 billion in outstanding property claims against the Cuban government as a “necessary predicate” to ending the embargo once and for all. “Where the embargo began is where the embargo should end: With a resolution of the certified claims,” Muse says.

After the Cuban government derailed Berenthal’s factory plans, he was discouraged but not devastated. He understands why his company, in which he and Clemmons have invested $5 million, was used as a political pawn: Cuba wants the embargo gone; as long as it remains in effect, Cuba has little incentive to grant piecemeal exceptions that reduce the pressure on Congress to demolish it once and for all. At least, that’s the best explanation he or anyone else can come up with to justify what happened.

So Berenthal and Clemmons have shifted plans. Now they’re building tractors for export at a factory in Paint Rock, Alabama. Clemmons, the more frustrated of the two, is focusing his energy on selling them to other markets–small farmers in Australia, Ethiopia, and Peru. Meanwhile, Berenthal’s contacts at Mariel have told him, “Commercialize your tractor and your products, and bring them to Cuba,” and he’s taking them at their word. Cleber’s new business model may in the end be more lucrative, albeit less transformational for Cuba than Berenthal had hoped for.

Still, there’s one more wild card. Cuba’s current president, Fidel’s brother Raúl Castro, is scheduled to end his term in 2018. “In my opinion,” says Berenthal, “this will trigger the final removal of the embargo.” Castro’s likely successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel, was born nine months before the revolution. If there’s going to be real change–generational change–in U.S.-Cuba relations, that’ll be the turning point. “I hope others will take the long view and continue the efforts to bring the two countries together through commerce,” Berenthal says. He understands, as best as anyone can, how it works in Cuba. That things happen when they happen. But, eventually, they do happen.

FROM THE FEBRUARY 2017 ISSUE OF INC. MAGAZINE

Cuban Doctors Stranded: Can’t Travel to US, Cuba, or Stay in Colombia

Cuban medical worker Adrian Lezcano Rodriguez, next to boat he used to get to Colombia. Carmen Sesin

When Adrian Lezcano Rodriguez, a physical therapist from Cuba, was chosen to serve on a “mission” in the small town of Maroa in the Amazon rainforest of Venezuela, he knew he would defect. He would make his way to the U.S. embassy in Colombia, and apply for the Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program (CMPP), which up until January 12, allowed certain Cuban medical personnel to apply for U.S. visas.

Lezcano spent around 20 days in the jungle town working in a small clinic, which only had electricity for about two hours a day. He ate once a day, usually lunch.

“If it rained, we drank rain water. If not, we would drink water from the river,” he said by telephone.

Lezcano met a few local indigenous men who were willing to take him, for a fee, through the treacherous Río Negro to the border with Colombia. During the five-day journey, they slept along the banks of the river at night. During the day, they would get lost at times. The boat would often get stuck in the sand, and they would have to push it so they could continue on their journey.

Play

Bottom of Form

When he finally arrived at the border with Colombia the night of January 12, Lezcano found out that just a few hours earlier, former President Barack Obama had ended the CMPP. It took another day to get to the capital in Bogotá, where he tried to speak to someone at the U.S. embassy, but he was turned away. “I was so frustrated,” he said.

Lezcano lives in a house with nine other Cubans who have been left in an unusual situation. He has run out of money and sometimes goes two days without eating.

Just like Lezcano, there are over a dozen Cuban doctors and other medical professionals who abandoned their posts in Venezuela and were in transit to the U.S. embassy in Bogotá when the parole program was abruptly ended. They say they cannot return to Cuba and they face deportation if they remain in Colombia. The only reason they risked deserting was to apply for the now defunct program.

The government of Cuba has said it will accept Cuban doctors and reincorporate them into the national health system. But, those stranded in Colombia insist this is not true. They say desertion is considered treason in the communist island. Those who defect are punished, medical degrees are revoked, and society scorns them.

Sending doctors and other medical professionals to countries like Venezuela, Brazil, and Bolivia on “misiones internacionalistas” is an important source of revenue for the communist island. In 2014, it totaled $8 billion – though recently they have scaled back on their operations in Venezuela because of the economic crisis.

Raúl Castro applauded the end of the CMPP. The government always said the program robbed the island of professionals they had educated. But according to health care workers, the “missions’ are equivalent to indentured servitude. They are pressured to meet a quota of patients per day, their accommodations are meager and they are paid a small fraction of what the Cuban government receives for their services. They say the parole program was their only way out.

That was what Yenniffer Santiesteban, a 25 year-old doctor from Holguin, had in mind when she decided to defect after 15 months in the state of Sucre in Venezuela. She had been seeing up to 35 patients a day, but the money she made disappeared in buying food.

“I was wasting my money to subsist in a foreign country — you spend months working hard and you don’t see the results,” she said. She became disillusioned. She wanted to flee and take advantage of the CMPP, but it meant spending years without seeing her family. Doctors who defect are barred from entering Cuba for eight years.

On January 10th she decided to leave, but her supervisors had been tipped off and caught her before she could escape. Before being taken to the airport and returned to Cuba, she and her two supervisors stopped at a restaurant to eat. She pretended she needed to use the bathroom, grabbed her backpack, and fled.

Santiesteban said she did not have a phone and had no idea how to get to Colombia. She went to a cyber café, contacted friends, and figured out the best route. She stayed in a motel that night and began her journey the following day. When she finally arrived in Bogotá on the 13th, a friend who had defected earlier, took her in and explained the CMPP had been terminated the day before.

“I was disappointed, desolate, depressed, and enraged,” she said. Santiesteban is now staying in a two-bedroom apartment with six other Cubans hoping that the Trump administration reinstates the CMPP.

When asked to comment on these particular Cubans, the White House said in an email, “the administration is reviewing all aspects of the US-Cuba policy, we do not have any further information to offer other than that at this time.” At a February briefing, White House press secretary Sean Spicer said the policies “are in the midst of a full review.”

Cuban-American lawmakers, like Rep. Carlos Curbelo and Sen. Marco Rubio, both Florida Republicans, have expressed hope that the Trump administration reinstates the medical parole program.

Related: Opinion: Ending Wet Foot, Dry Foot Policy on Cuba Long Overdue

“If that takes a long time or if the Trump administration doesn’t agree to do that then obviously we want this specific group to be given as much consideration as possible given their unique circumstance,” Curbelo told NBC Latino.

He said all of the Cuban-Americans in Congress agree the program should be reinstated. “We will continue communicating to them that while we understand the broader policy (wet foot, dry foot) had to change, that particular element of it is worth keeping,” Curbelo said. Wet foot, dry foot refers to the policy that allowed Cubans who reached U.S. soil to stay as legal permanent residents, but returned to Cuba those captured on the open sea.

Reversing Obama’s policy on the medical program seems like an easy maneuver for Trump, according to William LeoGrande, a professor of government at American University who coauthored “Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations between Washington and Havana.” He said, “the problem is that if he does reinstate the parole program, the Cubans may back away from their willingness to cooperate on immigration more broadly.”

He thinks it’s possible the small group of Cubans who were in transit when the policy changed could still be admitted because the attorney general has broad discretionary authority to parole into the U.S. people who don’t have a valid visa on humanitarian grounds. “These would seem to be cases that qualify for that because they took certain actions in anticipation of what the U.S. had promised them and then the U.S. changed the program,” LeoGrande said.

In the past few years, the number of Cubans applying to the program more than tripled, according to numbers provided by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. In fiscal year 2014, a total of 1,208 applications were submitted and 76 percent were approved. But by fiscal year 2016, the number of applicants soared to 3,907 and 86 percent of those were paroled.

Until January 12, applicants who were denied visas made their way to the U.S. -Mexico border and entered the U.S. under the wet foot/dry foot policy, but Obama also terminated the policy. Now, the applicants who are denied visas are also stuck in a similar situation: unwilling to return to Cuba and unable to stay in Colombia.

There are about 10 Cubans in Bogotá who have been denied visas during the past month, according to Yusnel Santos, who is also in Colombia and keeps track of the Cubans in Colombia and Bolivia waiting for their applications to be processed – something that can take months. According to Santos, there are about 500 Cubans in Colombia waiting for visas and about 16 who did not arrive on time to apply for the program.

Marisleidy Boza Varona, a 26 year-old dentist from Camaguey, thought of defecting from the beginning. When she arrived to the city of Guayana in Venezuela, and saw the conditions she would have to endure, it made her more eager to leave.

“We would only eat once a day because we didn’t have enough money,” she said.

Sometimes she would have to “invent” to reach the quota of patients she had to see per day. “People would cancel and I would have to fill that space, if not, it would be a big problem for me,” she said.

On January 9, a friend sent her a text message saying to be vigilant because their superiors suspected she would defect. She began to receive calls from the coordinator of the program. That’s when she fled and hid inside the house of a friend. On the 13th, she decided it was safe enough to make her way to Colombia and it was along the way that she found out Obama had already ended the program.

“I was in shock. Everything came crashing to the ground … I know people who have returned to Cuba and they lose everything. They lose their diploma. They send you to work in the mountains as punishment,” she said.

“We all have faith that the U.S. government will realize the situation we are in,” Boza said crying.