Nate Berkopec's Blog

January 1, 2020

Do better, not best - transitioning to a growth mindset

In 2019, I had a few mindset shifts around recurring, daily or near-daily work.

In short: Frequency first. Duration next. Then, quality. Make progress every day. Any progress counts, duration + quality should go unmeasured.

Old goal: Run a marathon in 2019.New goal: Run every day.

Old goal: Write 1000 words every day.New goal: Write every day.

Yikes.

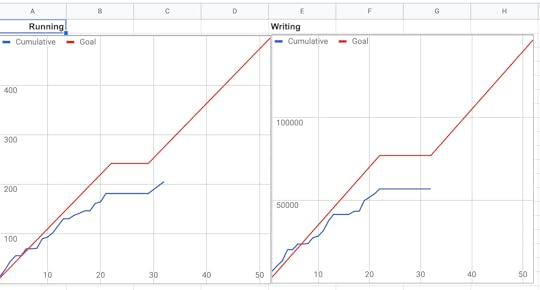

In the past, I was very focused on big-picture goals which had very specific targets. Make $X/year in my freelancing business, run this many miles, write this many words. I even had burndown charts.

This approach never lasted more than a month or so. I would inevitably stumble, and be so far behind my goal, or so far off the "streak", that I saw no point in getting back on. Better wait until next year, I guess.

Unfortunately, you will inevitably stumble temporarily on the way to any progress on anything. When running, you will get injured. When writing, you will inevitably want a day off. With money, sometimes things change in the economy that you have no control over.

My old approach led to me burning the house down every time I hit a speedbump.

In 2019, though, things started to change.

I only realized what was happening in retrospect. When I was compiling my list of content I produced for Speedshop in 2019, I realized I had produced 41 pieces of content in 2020. Most of those were 500 to 1000 word email newsletters, but also 3 3000-word blog articles and 2 45 minute conference talks. That's a fair amount of creative output by anyone's measure, and it's far more than I've ever done.

What changed?Frequency first, and no more long-term goals.

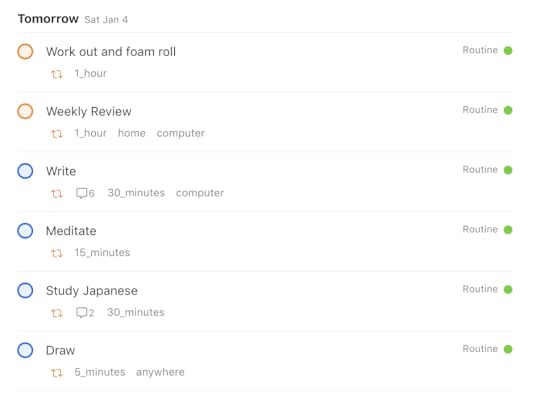

My todo-list now looks something like this, every day:

Note that I cannot track (at least not obviously) how many days in a row I have done any particular task. Notice how there are no specific goals: write X words, meditate X amount, practice Japanese for X minutes, either or a daily or monthly or other time basis. I've got some labels there to help me budget my time for the day, but they're not mandatory. There are no requirements for the duration of each task or the quality of the execution.

I give myself permission to check the boxes off on these tasks even if I only work on it for 10 seconds. Meditated for 2 minutes and barely paid attention? Check the box. Wrote 10 words? Check the box. As long as I sat down and made an honest attempt, check the box.

After adopting this approach, what happened next was kind of weird.

By not focusing on duration and quality of my work, both of those things started to improve. By focusing on frequency instead, and giving myself permission to fail, I succeeded more on all of these goals than I have for 10 years of trying.

One habit I've really built over the last year has been writing. I just try to write something, every day. I vaguely want to write for about 30 minutes or 500 words, but I give myself permission to "check the box" on my to-do-list even if I just write for 5 minutes. Just by sitting down and starting to write, I usually find that after a few minutes, the words start to flow and then 25 minutes later I've got 500 words.

Critically, I'm not tracking how many email newsletters I send or blog posts I write. I vaguely would like to release one of either each week, but I don't track this anywhere. I'm only aware of whether or not I did it this/last week or not. If I did it last week, great. Let's do it again this week. If not, OK, try again better this week. No more year-long targets that I can fall behind on.

Better, not bestThe struggle of daily work, I've realized, is not its quality, but its frequency. Try to do something every day, and the quality takes care of itself. Focusing on quality only leads to stress when quality is inevitably not achieved.

With frequency of execution inevitably comes quality. If you do something every day, with attention and effort, you will get better at it. So why set goals for the quality of your output, when it will actually take care of itself?

Ira Glass has spoken about the chasm between being a critic or dillettante and becoming a creator. You start with good taste and no skill of creation, and so when you start to build your creative skills, there is inevitably a "dip" where you can tell your own work is bad, because that is all you are capable of producing. There is only one solution: stop critiquing. Stop paying attention to the quality of your output. Relegate it to the back burner. You'll come back to it. For now, you must simply do the work.

Make failure temporaryThe problem with "streak" strategies and long-term goals (write X words per week or year) was that they had a way of making failure permanent. For example, in 2017, I wanted to write 1000 words per day (or 365000 words per year), and I realized around March that I would never reach my goal, so I quit. I stopped writing. My goal was now impossible, so I failed, permanently.

My new approach wipes the slate clean every morning. I am not aware of any streaks or long-term goals, so the worst possible failure I can have is that I didn't have a good day. But the next morning, that no longer figures into my thinking. I'm just trying to "win the day", every day, which means that failure, while possible, is only temporary.

No rest daysIn the past, I've set complex and detailed goals about how much I want to lift, to run, to bike, whatever. Now, I do none of that. I just work out every day. No rest days. Some days I go in and just spin the wheels very lightly for 30 minutes, but I just let my body tell me what to do.

Doing something every day means that doing it is not a decision. It's just something you do. I no longer have to decide if I'm going to the gym every day. I just go, every day, at the same time. Once I'm actually at the gym, I give myself permission to do whatever I want. If I want to sit in the gym cafe for 90 minutes, fine. I've never done that, but I could, if I wanted to. But, inevitably, once you're through the door, you start working out. Might as well, right?

Of course, there are some physical limits. I don't weight train every day, I do weights only 3 days a week. I do cardio (usually Peloton) every day, but 2-3 days a week are very light, sometimes just 20 minutes. But I go to the gym and do something every day, and the going is the hard part, as anyone who's tried to build a physical fitness habit knows.

Growth over resultsOverall, this is part of a new focus I gained in 2019 of focusing on growth (relative progress) over results (absolute progress). If I'm getting better (or maintaining a difficult, creative effort), I'm happy. I don't measure myself against others or even my own made-up targets (e.g "I want to make $X this year"). I just want to get better.

Better is a more productive mantra than best because better admits the possibility of failure. Better allows a circuitous, bumpy path to success, whereas best only allows perfection.

I hope that in 2020 I'll continue along this path. There will inevitably be bumps, small failures in the road - but I'll be better than I was today.

December 16, 2019

On the packaging of ideas

Lately, I've been thinking about the importance of how ideas are packaged, and the effect this has on persuading the intended audience of the idea. Mostly this was due to the Dolly Parton's America podcast telling the story about how Dolly Parton's involvement in the 9 to 5 movie and soundtrack supported the feminist movement of the 80's, while Dolly Parton is a country singer that does not identify as a feminist. Despite that, her soundtrack (and the movie itself), expresses feminist, left-wing ideas.

What a way to make a livin'.

Idea packaging is comprised of a number of related elements:

FrameMediumIdentity cuesIdea packaging is important because the same idea presented with different packaging can be received and responded to very differently. One can adapt one's idea packaging to present the same message to different audiences, or present what would otherwise be a non-palatable idea to an audience with good packaging.

The frame of an idea is the perspective from which the idea is presented. As an example, in the 2020 US presidential election, the Democratic candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders present similar economic ideas with very different frames. Bernie presents his ideas as "anti-billionaire", while Warren presents mostly-similar policies and ideas as "pro-middle-class" or "pro-99%".

Frames are powerful because they can control the way an audience reacts to an idea. Bernie's frames lead to a more emotional conversation about how billionaires are cheating the American people, while Warren's frames lead to a more dispassionate conversation about the pros and cons of her policies. Again, the policies and ideas themselves are really very similar, but they're presented with different frames.

Medium is another important element of idea packaging. The medium through which an idea is presented affects how audiences consider the idea. Dolly Parton's soundtrack for 9 to 5 contains lyrics that are quite explicitly about women's rights, workplace harassment, collective action and other traditionally-left-wing ideas. However, by being presented in a popular song (and a popular comedic movie), these ideas appear far more innocuous to an audience that would possibly reject these ideas when presented by a political candidate in a speech, or in a documentary, or in a news article.

Medium can also dictate an audience's capacity to respond, which affects further conversation around the idea. Ideas presented via television and film convey greater weight and an appearance of truth, because we cannot respond to the ideas presented directly. Ideas presented on Twitter can be immediately refuted with a quick "@mention" of the account, or a saracastic or critical quote-retweet. Our ability to defend ourselves rhetorically affects our persuasion.

Identity cues are the final, and perhaps most important, part of idea packaging. As Seth Godin phrases it: "People like us do things like this". Ideas are more likely to be accepted when they are attached to an identity that we already identify as or would like to identify as. This is a key idea behind brand marketing - people who are rich and beautiful wear designer clothing, therefore if you wear designer clothing, you will be like these rich and beautiful people.

Identity cues are especially important in politics. Often, it is more important which "side" the idea represents rather than what the idea actually is. I don't think I need to explain this one.

Avoiding identity cues can often be highly effective as well. Dolly's "9-to-5" deliberately avoids identity cues in order to make its unavoidably political message more widely appealing.

In the professional world, identity cues can also be used effectively. Bob Martin has consistently presented his ideas as "software craftsmanship". By accepting Bob Martin's ideas, you are a craftsman, conjuring images of a bearded woodworker in a beautiful workshop.

The three elements of idea packaging combine and overlap to affect the audience. As a personal example, I struggled with meditation and mindfulness for years (I tried multiple apps, tried many books, and in-person training in Zen) until Sam Harris created his Waking Up app. Why did it take so long for me to develop a mindfulness habit? Idea packaging.

Frame. Sam frames meditation as an empirical examination of consciousness. This is very much unlike other approaches to meditation, which often invoke mystical themes, or emphasize benefits, like relaxation and calm, or a religious frame, like Buddhism. Sam's "scientific" frame appealed to my sense of rationality and resonated with me very well.Medium. Sam's meditation content is delivered through an app, in audio format. There are no interactive social elements, such as commenting. I am quite used to running my life with apps. Other approaches, such as MP3s/raw recorded audio, would not have been as effective for me. In-person training was too difficult to attend regularly, and books were an ineffective medium for instilling a regular practice.Identity cues. Sam Harris, as a "brand", represents a logical, scientific approach to the world (whether he actually always does this is not the point, but it is the "brand promise"). I realize the "smart atheist" brand is obnoxious to many (tips fedora), for good reasons, but something about it clearly still appeals to me! I am comfortable identifying with a famous atheist. Essentially Sam is saying "logical, scientific people like us meditate like this".All ideas have packaging, so when presenting our ideas, we should be aware of how we've packaged them.

2019 Year in Review

Another year has come and gone. 2019 was a pretty wild year for me, with a number of big life events and transformations like I haven't had in a long time. It was also a year in which I confronted my inner life more earnestly, which is something I had only started to do in 2018.

Here's a review of my 2019.

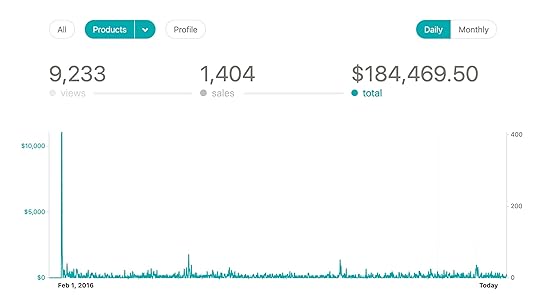

My Business (Almost) Doubled

Presenting at RubyKaigi

So, I'll start with the big bang, the thing I'm most proud of. My freelancing - a combination of book sales, client work, and workshops - doubled in top-line revenue this year. Expenses were a lot higher too, but I'm still taking home a lot more than I was last year.

Despite being in the self-employed business for almost 5 years now, this is probably the first year in which I made as much or more money than I would have at a corporate job. Still, I wouldn't trade the autonomy I've gained for anything. Making money on your own terms is really the ultimate luxury good.

Most of the growth this year came from my workshop business - both public and corporate. I booked a lot more on-site corporate workshops, and did a tour of more than a dozen cities this summer in the USA.

Made MicroConf Friends

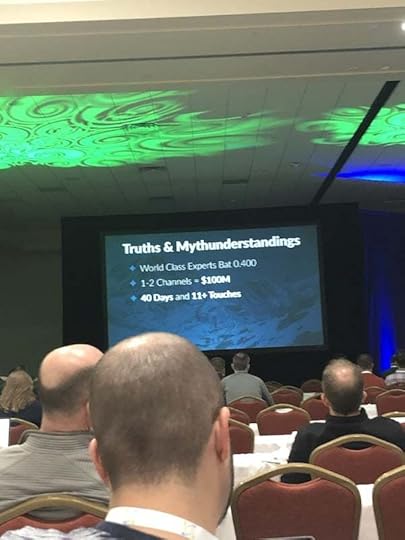

Presentations at MicroConf were pretty good too!

I went to Microconf for the first time. I met a lot of cool people there, and ended up (eventually) getting into a biweekly "mastermind" group with a few of them. I enjoyed the atmosphere of MicroConf a lot. Everyone was looking to help everyone else, no one was "judgy" about other people's businesses, and no matter how weird your niche was, there was someone else there doing a very similar thing in a slightly different way, and you could talk shop all day about it.

Tried Lifting, Ended Up CyclingAt the beginning of the year, I tried "bulking up" by following the Starting Strength system. I stuck with it pretty religiously for about 3 months, until I injured myself and couldn't get back on the horse again afterward.

In November, I ended up trying a Peloton bike at a hotel, and actually really enjoyed it. I love cycling (I did it a lot when I was a kid) and the Peloton workouts, in tandem with a new Apple Watch I bought, have been extremely motivating. I'm on about an 8 week streak now of 5+ workouts in a week, which is the most I've exercised possibly ever.

Fell in Love with Japan Even More

View of the supporter's section at an FC Tokyo game. Hope to go back to another game in 2020!

In the spring, I attended RubyKaigi for the second time. This year, it was in Fukuoka, Japan.

This was my second time in Japan and both me and my wife love it even more now. The food, the culture, the scenery - we just can't get enough. I've started to take up Japanese on a more serious basis, and we're going to be returning there for a 3-month stay in April.

Summer Workshop Tour

Workshop ending victory pose, I guess?

This was a pretty big step for me. I ran my Rails-performance-pony-show in more than a dozen cities in the United States. It was fun. I got a taste of a real summer of "business travel" and spent more than 90 nights in hotels this year. I learned that I don't really hate it all that much. I wouldn't want to much more, of course, but it wasn't too bad.

The tour itself was more of a learning experience than a financial success. I made a small amount of money on it but not nearly as much as I had hoped. However, I did learn a LOT by having to run through my "material" dozens of times. I learned a lot about what sticks and what doesn't, what's important and what's not. That was certainly worth the cost of admission. I basically see it as getting paid to do customer development.

Nomad Life

On the beach in Cape Coast, Ghana. Somewhere I'd wanted to return to for almost 10 years!

In the fulfillment of a dream I've had for almost a decade (when I read the Four-Hour Workweek), I finally became a full-time "digital nomad". My wife and I left the US in August and don't plan on returning for at least a year.

It took a number of life factors that had to converge to make this happen. My wife's career became remote, our dog passed away, and a few other things that prevent one from travelling around the world full-time finally lined up to let us go.

We've travelled to, so far: Ghana, Spain, Taiwan, Laos, Macau, Thailand, and Vietnam.

I've met a lot of new Rubyfriends on the road, which I've really enjoyed. I hope to continue to do so in Mexico and Japan, which are our destinations for the first half of 2020.

Published a lot of NewslettersI've been achieving a bit more regularity in my writing, and the breakthrough came from an unexpected source: my newsletter (subscribe below!). I've always felt a bit overwhelmed by posting on my blog, ever since the whirlwind period of 2015 when I was posing every 2 weeks or so with 3000 words or more. I've often set out to post more frequently only to fall over after the first post.

Instead, I allowed myself the creative space of my email newsletter to most more quick-hits, and it's really freed me up a lot. I hope to continue this habit in 2020.

Re-evaluated Shark TankI went public with the anxiety I've experienced as a result of my appearance on the Shark Tank reality show in 2009. It took a lot of time for me to process that experience and its been helpful to be able to publicly say "this thing messed me up, and I'm still dealing with it."

Anyway, that was my 2019. See you in 2020 for more adventures. It felt like 2019 was a year of building foundations and stacking bricks, which I hope to continue to do in 2020.

October 6, 2019

What does it mean to be a open-source project maintainer?

There are many different responsibilities for the maintenance of an open source project, and while some of them get called "maintainership", I'm not sure they should be.

Let's zoom out for a moment. What labor must be performed, by someone, anyone - in any successful open source project?

Writing code - fixing bugs, writing new features, refactoring old code.Writing documentation - explaining why things are the way they are. Recording intention and design, and how to use the APIs provided.Issue triage. Making bug reporters create reproducing examples. Closing issues that are stale or invalid. Providing feedback on feature requests.Code review. Looking at pull requests and providing feedback.Regular releases. Packaging up a release and pushing to the package namespace."Green Button" control. Merging pull requests. Deciding what should be merged and what should not. This "quality control": is this PR good? Does it fit the goals of the project? Did someone review it?Vision/direction. What's our release schedule? What features will we not include? What approaches will we never take?Enlisting help. Encouraging more contributions and engaging more volunteers to do the above.What's interesting is that only a few of these responsibilities require what most people consider to be the mark of the maintainer: commit bit and rights to the package namespace on the appropriate package manager. In fact, it's really just one of the responsibilities that needs that all-important commit bit access ("Green Button" control), and pushing to the package repository needs a separate privilege. Everything else needs no privileges whatsoever.

Unfortunately, the word "maintainer" has become something of a byword for a mythical cowboy-coder heroine, someone who spends 40 hours a week on their project writing new features, fixing reported bugs, spinning up VMs on cloud services to try to reproduce the more esoteric reports.

As an maintainer of a popular OSS project, many people certainly see me this way. They provide vague bug reports and then ask "what's my plan" for fixing them. In the desire to see their open source project succeed and gain widespread adoption, many OSS maintainers turn themselves into personal servants of their users, and take on all of the responsibilities of the project themselves.

Instead, I'd like to propose that a "maintainer" is just being someone who does the labor of contributing regularly to an OSS project, regardless of their privileges or status.

And, what I've come to realize is that the most valuable thing I can do as a "maintainer", whatever that means, is to grow my base of contributors. By taking on the mantle of "hero maintainer", fixing every issue and writing every feature, I am actually sabotaging that goal by ignoring all of my users (who are my potential collaborators) and letting them treat me as free labor.

The only thing you can do for an open-source project that has potentially infinite impact is to encourage more contributors to get involved. Those people might also encourage more contributors, etc etc. You are just one person. But the global pool of people who could work on OSS is, functionally, infinite.

I've been focusing on trying to support as many people as possible to get involved in our project, and to teach as many people as possible how to carry out the responsibilities of "maintainership". I hosted an open Zoom meeting where I helped people make their first ever contribution to Puma. I got 2 new contributors and we fixed 3 issues.

The reason people don't help you with any of the responsibilities of "maintainership" is that they don't know how. But as an existing maintainer, you know how to do all of this stuff already. But you have context, experience and probably skills that your potential contributor base does not. So it's up to you to teach them how.

Writing code. Teach your potential contributors what packages to install, how to run the tests, how to run just one test a time, how to write a good test, how the project works and what its architecture is.Issue triage. Lay out clearly how your issue triage process works. In a separate document, outside your pull request/issue template, explain what a good bug report looks like and how to work with a reporter to get it from vague to excellent.Code review. Write a document that explains what you look for in pull requests, and encourages others to get involved. Explain that you encourage anyone to review code.Vision/direction. Write it out. Post it in the README for all to see. This helps everyone know what bugs are more important than others, and which features are good and which don't fit.Making contributions to OSS is, unfortunately, a very fraught and nervous experience for newbies. You can help them by giving them a step-by-step guide for the various ways they can contribute to your project.

We can all be "maintainers" - but it's up to maintainers to teach us how.

October 3, 2017

I'm Glad I Failed In Front of Millions on Shark Tank

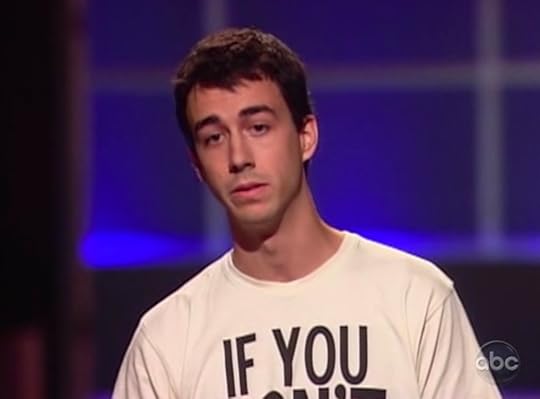

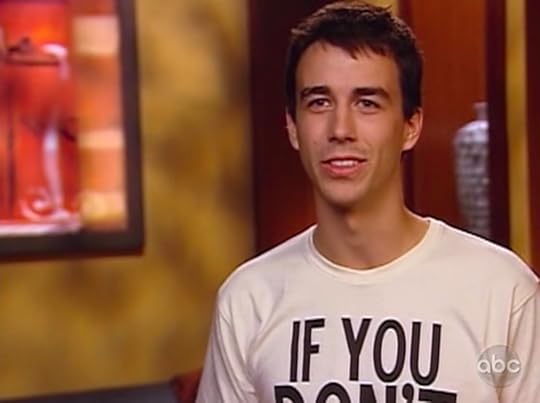

That's me on Shark Tank. It's episode 12 or 13 of season 1.

When I was 19 years old, I appeared on the American reality television show Shark Tank. The premise is simple: entrepreneurs pitch a hard-boiled set of investors to give them money for a piece of their business. It's based on a Japanese television show called Dragon's Den.

I appeared on Shark Tank in 2009. I wasn't shy about it - it's been a part of my "bio" for years. What I have been afraid to say to others, though, is that I didn't have a very good time during or after my appearance. The Sharks didn't invest in my company, and I endured something of a dressing-down on live television.

The experience deeply affected my psyche in ways I didn't realize until I had an anxiety attack in an airport 8 years later.

I looked smiley after my appearance, but inside, I was crushed.

When you were young, you probably had dreams of who you would become and about the career you'd have. You probably haven't had those dreams destroyed in 15 minutes of live primetime television, broadcast to all of your friends, family, everyone you know (and ever will know, thanks to reruns and YouTube) and literally millions of others.

It messed me up for a long time - 10 years - and I'm just now getting over it and accepting what happened. I want to share my story in the hopes that will help others who've had a big, public failure that they felt like they'd never come back from.

How I Got Cast as the Idealistic College Kid

Screenprinting the original design in my dorm room in December 2008, using iron-on paper and acrylic paint. In retrospect, the designs seem a bit harsh and confrontational. 2008 was a very different time.

When I was a freshman at New York University, I started a t-shirt brand that I called The Factionist. I screen-printed socially-conscious and environmentally-friendly slogans onto some ethically-produced shirts, but I had dreams of it becoming the socially-conscious H&M. Obama had just been elected and college students in America were feeling like everything was possible, and both my own enthusiasm and the message reflected on the product reflected that.

In the spring of 2009, I was reading an entrepreneurship blog and read a post about how a "major television network" was looking for "entrepreneurs" to appear on a new reality show. They didn't say the name of the network or the show, but this was Shark Tank (the show had not yet aired in America). I applied, and was selected by the producers to appear.

If you're wondering how somebody would think they were an entrepreneur after painting a few t-shirts in their dorm room, you're right. I was paying someone else to screenprint a typeface that I didn't own onto t-shirts that I didn't make. There simply wasn't any intellectual property or even a business at all there. I was 19. I didn't know what I was doing. I knew a few hundred people had paid me money for something, so that meant I had a business, right?

I had been raised by my parents to believe I was a "smart kid", and therefore I would be successful at anything I wanted because I was smart. And, since I was genuinely gifted with intelligence, I generally did succeed a lot without really trying.

Maybe paradoxically, this caused me not to work very hard. If I had to work hard at something, I thought that must mean I was stupid or that it "wasn't for me". So, I didn't work very hard on my t-shirt company. I spent most of my time doing things that college freshmen do - chase girls, go to class, and play videogames.

I would frequently pull out of activities at school that I didn't succeed at because that lack of success conflicted with my own image of myself. I would quit teams and extra-curriculars when I started to reach the limits of my talents, rather than put in any work to improve myself. I was more concerned with looking smart than actually succeeding.

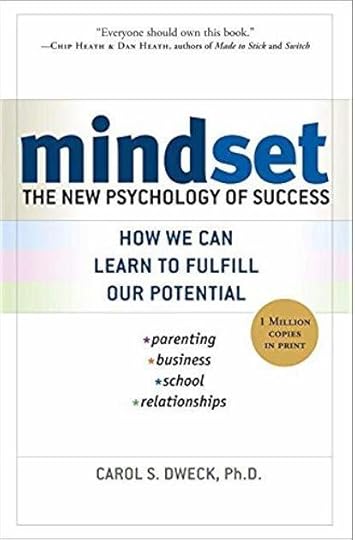

My psychologist told me to read this book - it really helped me to understand why this particular failure was so important to my ego.

Yet, I had all the confidence in the world. The mindset I had would be described by the Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck as a "fixed mindset". Dweck described a fixed mindset this way:

In a fixed mindset students believe their basic abilities, their intelligence, their talents, are just fixed traits. They have a certain amount and that's that, and then their goal becomes to look smart all the time and never look dumb. In a growth mindset students understand that their talents and abilities can be developed through effort, good teaching and persistence. They don't necessarily think everyone's the same or anyone can be Einstein, but they believe everyone can get smarter if they work at it.

2008-era Nate's heroes: 37signals. This image is from their 2008 Wired write-up, titled 'The Brash Boys at 37signals [...]'

I also already believed I was an entrepreneur and had made it a central part of my identity. I voraciously consumed Inc. magazine and other content around tech startups, which were taking off again as Twitter started the Web 2.0 revolution. Believing I was an entrepreneur helped me to differentiate myself from what I saw as the "worker drones" around me at business school who were gunning for a job at a big Wall Street firm.

Unstoppable Force Meets Immovable ObjectAppearing on Shark Tank was putting the unstoppable force (me, the "smart kid" and self-described "entrepreneur") against the immovable object (evaluation of my paltry "business" by a panel of experts). Failure was inevitable.

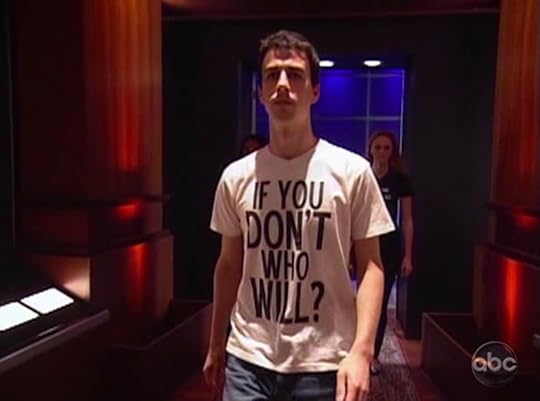

I remember being coached by Shark Tank's producer all summer. We honed my pitch over and over. They flew me out to Los Angeles, picked up at the hotel and driving into the Sony backlot. I had to walk through the set of How I Met Your Mother to get to the Shark Tank set.

After a lot of waiting around, I was on. I walked down the forced-perspective hallway towards the sharks, trying to look confident with a Steadicam operator in my face. Then, you have to just stand there. For what felt like an eternity, I had to just stand on my mark while the camera jibs flew around and captured B-roll and shots of all of us to be cut in later.

There's a big difference between what actually occurred next and what my memories of it were. I'll get more into that later. But, to stick to the facts: all the sharks passed on the deal. The designated heel, Kevin O'Leary, let me know that I was a bit deluded. Extremely successful clothing brand owner Daymond John immediately pointed out the obvious flaws in my plan and how little I had accomplished to date. Robert Herjavec and Barbara Corcoran had some empathy for my obvious passion, but passed too.

The rest is a blur. I remember a mandatory meeting with a psychologist and telling her I was fine. My next clear memory is sitting at a hotel at LAX, overlooking the runways. I ordered some awful shrimp thing from room service, and sat there, alone, with my failure.

About four months later, the episode aired on national television. Shark Tank was getting about 5 million viewers 4.4 million for my episode, according to Wikipedia. per episode at the time, plus more on re-runs. I remember watching it next to my parents in their basement. I heard my entire high school watched it during classes too.

So, everyone knew I was a failure. I imagined them all laughing at me: "Hah, that guy was such a dummy! He was so unprepared! He had nothing!" "What an idiot!" "It was so obvious he had nothing, he's so stupid!" No one ever said it to my face, but I felt like I just knew what everyone really thought. It has taken me an extremely long time to hear anyone say anything positive about my appearance actually be able to take it sincerely/at face value. 100% of the time I heard something like this, I interpreted it as a lie.

The Retreat Into The WildernessI bought a motorcycle that summer in an attempt to recoup some amount of my self-image of how cool I was. I studied abroad in Ghana, partly to get away from NYU where I had to face up to everyone in my class that had seen me get roasted on TV.

For the next 10 years I tried to both keep and reject my entrepreneurial identity. Founding something else was out of the question,My mindset was that I had already tried that in failed, so why try again? so I tried working in tech startups as a programmer. I would "learn on someone else's dime".

The original Branch team. Hursh is second from right.

During this self-imposed exile, a very good friend of mine, Hursh Agrawal, started a startup called Branch with some people he met at a startup bootcamp. A few years later, they exited to Facebook. I didn't realize it at the time, but I really resented my friend and his success, because underneath I was thinking: "Why didn't I do this? He was just as prepared as you are - why aren't you doing this, like you said you would?" I buried those feelings and kept telling myself that I had to "learn more", despite the fact that my peer was succeeding with the same amount of experience that I had.

But I couldn't deny my entrepreneurial desires. Eventually I quit full-time computer programming work and started freelancing. This was a bit better for me, as I had to deal with sales and marketing. I found a niche in Ruby on Rails performance, and wrote a book about it that has done pretty well. In the last 3 years, I've cleared over $500,000 from a combination of my writings, workshops and consulting.

I still felt like a failure.

If you've ever wondered if you can feel like a failure while selling $1k/week in a product, yes: you can.

I was chasing various health ailments and constantly ending up at a doctor who told me nothing was wrong with me: heartburn, vague muscle aches, RSI, and more. I eventually realized what was going on and started to see a psychotherapist, which has helped me immensely.

I had to admit to myself that my health issues were caused by internal resistance and fear of failure, generated by a part of me that had never gotten over failing on Shark Tank all those years ago. My psychotherapist used mostly the Internal Family Systems method when working with me. I've found it very helpful. An introduction to the topic is available in Self-Therapy by Jay Earley.

Watching My Appearance, 10 Years LaterAs part of the healing process, I recently re-watched my Shark Tank appearance for the first time since it aired. In almost 10 years since it went on TV for the first time, I had never seen it again.

10 years later, I didn't want to do it. I couldn't even push play. My skin flushed, my heart started racing.

A part of me still lived that Shark Tank experience every day. This part of me felt worthless and stupid. He felt like everyone had lied to him about who he was and what he was supposed to become. He felt like everyone was watching, ridiculing. Embarrassed, ashamed, worthless.

I pushed play. I started sweating. I was back in the room. I could see the absolute destruction of my ego in my own reaction - the slight twitch of the red eyes, the quivering expression. I was on the edge of tears for a lot of that.

But I was completely taken aback by the person I was watching on the television. It didn't seem like me. I was shocked by my own confidence and self-belief. I hadn't acted like that in 10 years. It seemed impossible that I was ever this 19-year-old.

At one point, it felt like I (19-year-old Nate) was talking to myself (30-year-old Nate). At the end of the segment, I said: "It's not a mistake to have confidence in yourself". But I haven't had anywhere near that degree of self-confidence in almost a decade.

I even honestly assessed my own performance as it was happening - I said that I had the drive but not the real numbers and work product to show for it yet.

So many positive things happened during that segment that I don't remember. I think I blocked them out of my memory because they didn't fit the story of failure that I had told myself. Robert Herjavec and Barbara Corcoran, Barbara Corcoran called me after the show taped and asked me to work for her. I was an intern for her for about a year. two of the sharks, were clearly taken in by my presentation and confidence, even if the business didn't make any sense. Robert commented at the end, after I had left the room: "See, that's why you don't dump on people like that. This wasn't the right vehicle for him, but someday he'll find the right one."

Speaking to MyselfI can tell Shark Tank Nate that he was right about himself. You were wrong at the time. You didn't know what you were doing. But, you did something incredibly brave by going on that show and doing what you did. And you were 19, man. No one knows anything when they're 19! What percentage of successful business founders were fully formed at 19?

It's not a thing to be ashamed of that you don't have the knowledge or skills. You just have to get back up and recognize your mistakes and grow. I know that now.

I'm not a failure. I'm not smart, I'm not an entrepreneur, I'm not any of those things. I'm Nate. I'm constantly growing and changing and looking for that perfect vehicle.

So don't be so hard on yourself, Shark Tank Nate. You did the best that you could. You weren't set up to succeed. You didn't understand that the fixed mindset that you had was actually holding you back. You were pushed into a brick wall. But if you get back up, even now, so many years later, it will have been worth it.

Shark Tank is the best thing that ever happened to me because it taught me how to fail. I will never have a more embarrassing, bigger failure than that. But I've had one, and now I've learned from it. Some people go through entire mediocre careers never being able to admit to themselves that what they were doing wasn't working. Or they do, and then give up and never recover. Now, I can do something else. I'm here to recognize the mistakes, recognize the good, and move on.

Put another way, where would I be today if I hadn't had the reality check that Shark Tank provided?

I might be in a loop of constantly "trying" but not really trying, and passing yourself off as a success because you're too afraid to fail. Many "wantrepreneurs" end up like that - the ones that are "serial entrepreneurs" but never tell you the names of the companies. I genuinely think, had I not appeared on Shark Tank, that would probably be me. Instead, I was presented with a failure that I couldn't hide from, couldn't minimize, and had to accept.

Where to Now?I'd like to think that I'm finally metabolizing what happened. Not forgetting, or trying to reject it - that obviously hasn't worked. But metabolizing it, integrating it into myself, and realizing what that experience did for me.

I've had my biggest year ever in terms of revenue from self-employment. I'll be working on doing the same for next year, but also turning my self-employment into more of a business, with processes and systems and equity. It's exciting, and something I don't think I've given myself permission to do until now.

So here's to that exciting future that I put on the shelf ten years ago and I'm just now dusting off. And it's thanks to Shark Tank - I wouldn't be here without it.

August 10, 2017

How To Get A Computer Science Degree in a Warzone

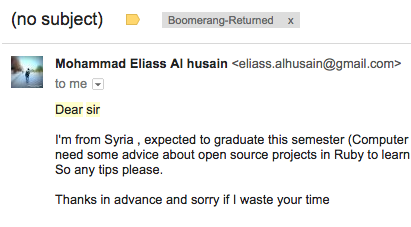

In June of 2016, I received an email:

The original email

Dear sir: I'm from Syria , expected to graduate this semester (Computer Science) , and as you sir my role model in Ruby also Rails , I need some advice about open source projects in Ruby to learn from. Thanks in advance and sorry if I waste your time

Actually, he wasn't just in Syria. He was at the University of Aleppo. His name was Mohammed.

Russian drone footage of Aleppo in February 2016. Mohammed: 'The damage now is much much bigger than this video.' Youtube

At this point, the Syrian Civil War had been raging in Aleppo for almost four years. One tenth of the total deaths of the war so far have happened in Aleppo. When Mohammed wrote this email in 2016, the tide was just starting to turn in favor of Assad's forces. You would be forgiven if, like me, you thought that life did not go on inside of a warzone, especially in a city where entire city blocks had been leveled to dust. But, it does - although life is hard, life goes on.

Aftermath of the 2013 Aleppo University bombing. Mohammed: 'When I saw the photo of the University bombing in the post I saw everything: I saw who did it, how he did it, the bodies, legs, arms, blood, glass, melted metal, I was there. My heart beat is getting faster and the inhales and exhales is disturbing my body better to close this thing.' NYTimes

The veil of ignorance had been stripped away. Here was someone my age, on the other side of the world, with the same interests as I do, but living in an actual warzone. He played video games with his friends, like I do, enjoyed programming in Ruby on Rails, like I do, but his university was being bombed.

Mohammed and I continued corresponding. He never asked for anything except advice, and that was all I gave (or really, could give).

In January of this year, Mohammed fled Syria and made it to Turkey, where he is officially a Syrian refugee.

Mohammed with his public key fingerprint. We both signed this post, see the end. Keybase

I'll turn it over to Mohammed to let him tell you his story. Mohammed's English is not bad, but I did heavily edit this section for readability and clarity.

Enter MohammedMy name is Mohammed Elias Al-Hussein. I was born and raised in Qamishli, Syria. Qamishli is in northeastern Syria, right on the border with Turkey. Before the civil war, in 2011, about 200,000 people lived there. Since then, refugees from other cities and Iraq have grown the city to over 500,000 people. All of my family is still there: my Mom, Dad, 2 amazing brothers and 5 beautiful sisters.

Screenshot of Project I.G.I., released in 2000

When I was growing up, I got the dream to be a game developer after playing a game called Project I.G.I. As I got older, my passion and curiosity for technology grew stronger, and I read about webpages and HTML in secondary school. I was fascinated by the internet and how it worked. Throughout my studies with my focus on programming, I also grew fond of the Japanese culture.

When I was in the 11th grade, I remember watching a TV show about Japan. The show talked about Japanese culture, Japan's technology sector, as well as the anime and manga like Death Note and Detective Conan. This really fed my imagination. After all of this, I made a promise to complete my graduate studies in Japan.

In September 2010, I was accepted and attended the University of Aleppo for computer science (in Syria, we call it Informatics Engineering). In Syria, we have a high school final exam that's required to enter a university's corresponding field of study. At the time, University of Aleppo's minimum score was 92.8% to get accepted in their computer science program. I studied tediously for the exam, and earned a 94%! I was excited to attend college and study computer science and Japanese. I especially was looking forward to what the future had to bring.

In Syria, most programmers are trying to learn C# or ASP.net, with some PHP and Android. The curriculum at school was very old. It was put together in 2000 and had not been changed since. It didn't include any of the technologies I really wanted to learn, like Unity, iOS, Ruby or Node.js. The faculty tried to change the situation, but with no response from the University.

Most of the students had very old hardware. Only a handful had brand new laptops, some have older laptops or desktops. The school had some desktops from 2011.

In the spring of 2011, the Arab Spring spread to Syria. That summer, the civil war began.

Washington Post, April 2013: 'Kidnappings of ordinary Syrians are rising at an alarming rate, a stark sign of the spreading lawlessness in their country after two years of war.'

On January 15 2013, Aleppo University was bombed. 82 people were killed and 160 were injured. Shortly after, while travelling back to Al-Qamishli to my family, I was kidnapped by thugs. I was in captivity for 32 days, 7 hours and about 21 minutes. I know because I counted, second by second. The gang that kidnapped me released me after forcing my family to pay a ransom of about $12,000 USD. Well, this was my savings to travel to Japan, and since the Syrian Lira had inflated so much since the war started it was even worse.

NY Times, February 23 2013: 'Antigovernment activists in Syria said the military fired Scud missiles into at least three rebel-held districts of Aleppo on Friday, flattening dozens of houses, killing at least 12 civilians and burying perhaps dozens of others under piles of rubble.' Youtube video of the attack.

Aleppo was getting very bad at this time. There was no safe road to exit or enter Aleppo. In addition, if the faculty left or the university shut down, I would immediately be drafted into military service for the Assad regime. I started looking for ways to leave Syria. I emailed every foreign embassy on Earth to complete my undergraduate study. They all refused me because I did not have refugee status with the UNHCR.

I believe from 2013 to 2015 we had electricity 4 hours a week, except the first days of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. There would usually be a cease fire at those times between Al-Assad's regime and The Free Army or any of the 22 other armies there. Almost every website was blocked. Even before the war, the fastest internet you could get was usally about 1Mbps. If you wanted more, you needed permission from the political security office, which was not a place you wanted to go. We have a saying in Arabic: "the person who enters is missed, and the one who exits that place is born." If you got involved with the political security office, people should just forget you ever existed. My friend's father was there for 11 years (1983-1994), and no one has any idea if he is still alive or not. That was before the revolution, now, it is worse.

Mohammed (center) with some faculty members of the University of Aleppo.

I started working in a dessert shop for 13 hours a day for 6 days a week for $70 US a month. I was thinking about trying to build my savings again so I could leave, but I knew it was crazy. I would need to work for 14 years at this rate. It was during this dark time that I understood that no one will care about you if you don't prove to them who you are and show them your soul as a fighter, dreamer - clever and ambitious. I felt like I was reborn as a programmer and self-learner. I feel like I proved to my teachers and supervisors at the University, too, that despite the circumstances with no fresh water, no food, no electricity and no internet I could be a world-class engineer.

At this time (2014) I was at the third of five years in my studies. I started learning Japanese in the Japanese Language Center at Aleppo University, which was in a bad state because of the situation in Aleppo. The Syrian Lira had inflated so much by this point that all of the faculty were basically volunteers.

Playstation with some friends after an exam.

The situation forced me to study for the university and work as a computer maintainer in Al-Jamelaiah, which is the "IT zone" of Aleppo. I started playing with Unity, a video game engine, but I couldn't finish a game. We only had 2 hours of electricity a day at this time, and we didn't even know when those 2 hours would be.

In the summer I got in touch with a friend in Turkey asking him about making real games. He told me to look at mobile development or web development instead, because my school wouldn't accept a video game as my final project. I eventually found Ruby and Rails, which I enjoyed very much. After a few months of struggling with little electricity and no internet, I found some online courses, read some books and a partner and I decided to build a social network with Rails.

Mohammed and friends from university

We struggled a lot to build the social network. For one three month period there wasn't any internet access in Aleppo at all. After that I reached my final year of studies. For my final project, we built a face recognition server using Ruby and OpenCV. We built the server with very poor hardware and without any fancy cameras or good processors, but it worked. After we finished the app the accuracy was about 81-84% due to poor processing power.

By the end of 2016, I finished 5 levels of Japanese, took a preparation course for the IELTS (a standardized test for English proficiency), and finished my Computer Science degree.

This was taken 5 hours before Mohammed left Aleppo.

In Syria, military service is compulsory for males over the age of 18 who are not in school. My exemption from service would expire after my graduation in March of 2017. I decided to leave Syria before that happened, before I could get caught by Assad's regime and turned into a cold-blood killer or to be killed by his mercenaries.

In December of 2016, I crossed the border to Turkey after a very tough journey. I spent a night on the Syrian-Turkish border, surrounded by rocket fire and bombs falling. The next day, after I had left, 22 died from rocket fire near where I slept. 3 weeks later, I got a job as a junior iOS developer in a small office in Istanbul. I work 50 hours per week for about $430 per month. After 5 months I moved to Bursa, a smaller and cheaper city than Istanbul, where I got another job in a more reliable office than the previous one for $500 per month.

Now, I am trying to immigrate to Canada. It is my dream to live somewhere peacefully with different races, cultures and religions. It is important to me that everyone is treated as a human being.

In front of the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

My name is Mohammed Elias Al-Hussein - let's explain it word by word: Mohammed, for Sunni Muslims, stands for the prophet Muhammad (pbuh). Elias is my father's name and in the Christian Syriac language (Syriac Aramaic) it means Elijah. Al-Hussein is for Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad (pbuh), who is very important for Shia Muslims. My name has all the basic materials of Syrian society. I have promised my mom to name my son Sam to add the Jewish component to my name.

I have been wondering: what's the purpose of creating me and making me struggle to obtain even the most basic human rights? I believe the answer would be to fight and use my knowledge as engineer on behalf of the poor, the disabled, and the refugees all over the world. From the bottom of my heart, I want to make the world better place. I don't know where I will be after 5 years, but I'm going to tell you something: I will do my best to be a world-class engineer to help others. I'm taking Google's CEO position into consideration!

What's Next and How You Can Help

Trudeau's government, unlike my own, has been increasingly welcome to refugees from all parts of the world.

Hi, it's Nate again.

Mohammed is out of the frying pan, but he's not out of the fire yet. If you've been following the news, you know that Turkey's future is highly unstable. After some discussion, Mohammed thinks his best chance at a safe and steady life and career is to immigrate to Canada. Canada has an extensive refugee immigration program, and I know there are a lot of companies there that might want to help.

For a refugee who cannot return to their country due to civil war, there are a few conditions you have to meet before you can apply to immigrate to Canada:

In 2016, a temporary policy allowed private sponsors in Canada to refer refugees who did not have official refugee status with the UNCHR or a foreign state. Although this policy has expired, Mohammed still qualifies because he has official refugee status in Turkey.

"You must be outside your home country." Mohammed is in Turkey."You have been seriously affected by civil war or armed conflict" Hopefully obvious from the above."You will still need the UNHCR, a referral organization, or a private sponsorship group to refer you." The UNHCR protects refugees who are fleeing persecution based on their race, ethnicity or other status, which Mohammed is not (he's in the Member of the Country of Asylum class). He will need a private sponsor.The reason why I've written this post is to help Mohammed find a private sponsor. In Canada, you can do that through two ways: by forming a Group of Five, private citizens and permanent residents of Canada who all live in the same city and pledge to help the refugee they sponsor to resettle in Canada. The second way is a Community Sponsor, which can be a corporation or community organization.

All private sponsorships entail financial and non-financial support, for the period of about a year or until Mohammed becomes self-sufficient. Since Mohammed is a junior computer programmer, hopefully that won't take very long. For more about what a sponsor has to do, check out Canada's official explanation of the role of a sponsor.

If you are a permanent resident of Canada (and, uh, haven't murdered anybody) and are interested in helping Mohammed resettle in Canada, please let Mohammed know by contacting him through this form.

If you are a Canadian corporation and want to help, you can contact Mohammed through this form. Mohammed has experience as a Ruby and iOS developer, and is currently working both at an iOS shop and with me on some Ruby projects. Here's his resume. I think he would be a great asset to any Canadian employer. However, your organization does not have to hire Mohammed to be his Community Sponsor.

In addition, if you live in any country whose immigration laws might allow someone like Mohammed immigrate, and you think you could help - please do get in contact.

Mohammed is active on Twitter and Github.

This blog post has been cryptographically signed by both myself and Mohammed. You may verify our signatures on Keybase. I also signed the commit on Github (repository here) for this blog post.

Nate Berkopec's Blog

- Nate Berkopec's profile

- 5 followers