Robert Knox's Blog, page 4

February 5, 2022

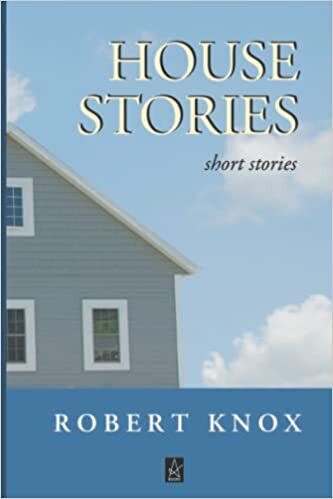

The Thing That Connected the Characters in "House Stories": Most of Us Had Been to Yale

Here is the pertinent part of the background for my book of stories about living in an informal commune outside of New Haven, Conn., circa 1970. Most of us had connections to Yale.

There were a lot of well-known names at Yale the year I showed up, and others who would soon enjoy a splash of fame, or -- like the characters in Doonesbury -- would become more permanent fixtures in the landscape. George W. Bush was a couple of classes ahead of mine, regarded at the time as kind of looney-tune frat boy character from a powerful political family then rooted in Connecticut. (After all, his father ran the CIA.) I didn't care much about the state of Connecticut, I just wanted it to legalize the birth control pill, which it soon did.

W. was a boozer in a dawning era of New Age stoners, an embarrassment to the spirt of the times. Other big names included high-profile jocks such as swimmer Don Schollander, who won an Olympic gold. I stared at him one morning, searching for the glow of fame (or simply a Florida tan) while serving him toast and orange juice in the Calhoun residential college dining hall where I worked my 'bursary' job. Scholarship athletes, and other rich kids, did not have bursary jobs.

My freshman class contributed two football players who made names for themselves. Calvin Hill went on to play for the Dallas Cowboys, and starred for a Superbowl team. A rare Black face on campus, Calvin was in my American history class and once came to my dorm room to borrow my notes. He stood in the doorway while I lacked the wit, and the confidence, to try to befriend him.

Freshman Quarterback Brian Dowling’s fame was more enduring; he became the model for the cartoon character B.D., Doonesbury’s archetypical helmet-head, always depicted wearing his helmet to the breakfast table. Cartoonist Gary Trudeau, a couple of classes behind mine, was a mere freshman when he began picking on established Yale sports culture. I don’t know who the model for Zonker was; there were, in those days, plenty of candidates.

The Yale campus had a best-selling author on the faculty as well, a Classics professor, of all things, Erich Segal, whose authorship of "Love Story" (the story of "a girl who died") seemed to illustrate the lightness of pop culture fame. The book became a movie with a name actress in the lead role. But neither the book nor the movie changed the world, and the people I hung around with thought there were more important things to do, such as stopping the Vietnam War.

One of the 'floormates' in my freshman year went on to play a role in the Clinton administration, arguably a way of doing good. That became the mantra of those times: Down with personal ambition for wealth and status. Up with doing good, making the world a better place.

And even at a time when media attention was ignoring traditional Ivies like young GW Bush and covering sex, drugs and political protests on campus, it wasn't hard to run into the scions of wealthy or influential families. One of our pothead set, a Long Island kid like myself, belonged to a family that owned newspapers and glossy magazines. Almost anybody with journalistic or writing ambitions would have had the sense to maintain that connection. I lost it.

But what I will always have, though it would never appear on a youthful resume, is the memory of the "hippie house," the rented farmhouse in a town outside of New Haven, where a small collection of Yalies and their friends and lovers began the project of creating an alternative adulthood to the then-available mainstream models.

How did it go? About as well, or ill, as could be expected. But it provided me with the memories that became these "House Stories," or the basis for these stories -- which almost by definition means something worth talking about.

Please take a look: House Stories

January 16, 2022

I'm an Amazon Author: The Big Book Seller Has Given Me a Window in its Mega-Store

I am an "Amazon author." This and a nickel, as folks used to say, will get you on the subway. I'm not sure what the subway costs these days (in my city, or yours), but it's probably a lot more. And I'm hoping that a little exposure by a GREAT BIG COMPANY will gain me a few readers.

The opportunity to provide a "bio" on my author's site elicited this confession about the origins of "House Stories," my new book of linked short stories published by Adelaide Books of NYC:

The book’s Southern Connecticut setting, the main characters and some of the stories are based on my own experiences as a recent Yale grad with absolutely no desire to fit into “the real world,” yet needing, like almost everyone else, to make some dough.

Here's the link Author's Page

Amazon, of course, also posts "House Stories" for sale, in a paperback or ebook edition, on its own page.

Here's the link to the book House Stories

So far, I am delighted to report -- and grateful to the Amazon readers who have given the book all stars.

Here's the reader's review that I like best:

"I could not resist the urge to begin this review with the expression “Bravo!” While certainly deserving of this time-honored collective acknowledgment of an outstanding literary performance, more importantly, Robert Knox’s linked short stories struck me as a collected work of profound literary and personal bravery.

"The stories unfold over a period of two intensely social and politically charged years bridging the end of the drug-fueled late sixties through the dawning of the paradoxical early seventies. With brutal honesty and poignant narration, we meet the “us,” a rolling cast of thinkers, artists, dreamers, schemers, and doers who shared or found an affinity with others in the Whitney Road farmhouse in southern Connecticut, each of whom Bob reveals with a depth of meticulous attention to the nuances of physical and metaphysical observations as good or better than the reader will find anywhere in contemporary literature. The dialogue and surrounding narrative context: crisp, clear and authentic, often embraced the poetic. Tear-provoking poetic."

Of course I like it -- what's not to like?

And this one as well.

"A wonderful collection of linked stories, emotionally insightful, politically astute, gorgeously written!"

If you get a copy of "House Stories: and like what you read, please don't hesitate to join my book's pool of reviewers. Just jump right in -- so far the water's warm.

January 4, 2022

My New Book of Linked Short Stories Is Out: Here's What the Publisher Says About It

Adelaide Books announces the release of the collection of short stories House Stories

New York, NY – ADELAIDE BOOKS is proud to offer the latest work by novelist and Boston Globe correspondent Robert Knox, House Stories, hitting stores everywhere this month and available online.

"Bob Knox has a unique ability to tap into the zeitgeist of the time, to show us not only who we are, but who we might become." – Patry Francis, author of The Orphans of Race Point and All the Children Are Home.

The House of the book’s title is a Connecticut commune, circa 1970. The youthful characters are of the era too, stumbling out of post-adolescence into early adulthood, drugged, disorderly, erotically dazed. Finding their way through relationships, commitments, the Vietnam war, and looming adult responsibilities, the characters struggle to hold onto their visions of an alternative way of living, while frequently making a mess of things.

“The narrator, looking back on the time and place, links the stories with a voice that is thoughtful and therefore honest. He can describe events precisely, such as a fire that nearly consumes the house—'...a demon of smoke and flame dividing its power, sending smoke up from two sources’—or nail what doomed an early marriage in a pointed epigram—'everything, it turns out when you’re married, comes down to finances.’” – Robert Wexelblatt, author of The Thirteenth Studebaker, Petites Suites, and Hsi-wei Tales.

House Stories can be purchased online from Amazon and also from the Adelaide Books website. Here are the links: Amazon House Stories

Robert Knox is the author of "Suosso's Lane," a novel based on the notorious Sacco and Vanzetti case, a contributing editor for the poetry journal Verse-Virtual, and a correspondent for the Boston Globe. Following the publication of “Suosso’s Lane,” he spoke widely at regional public libraries, historical societies, museums, book stores and book groups.

As a short fiction writer, he was selected as a finalist for a Massachusetts Cultural Council fellowship and his story "Lost" was excerpted on the council's website. His stories have been published by Words With Jam, The Tishman Review, Lunch Ticket, and Unlikely Stories, among other journals. His poetry book “Gardeners Do It With their Hands Dirty” was nominated for a Massachusetts Best Book Award. Another novel, "Karpa Talesman," was chosen as the winner of a competition for a novel of speculative fiction and will be published by Hidden River Arts.

December 17, 2021

"Christmas in the City" -- Saving a Seasonal Memory to the Digital Dump of Time

I wrote this – how many? I don’t know – years ago. It was published, and I do remember this, a mere four years ago in an online journal called Beneath the Rainbow – under the title, “Christmas in the City.” Very appropriate, if you read the content. I will call it “auto-fiction,” meaning in this case that while the stuff really happened, I changed the names. Anne, for instance is Sharon. Her father (Leonard, known as Jack) is here rebranded as Max; etc. All that follows is at least sort of true… The story however is already being lost to time, as its publisher apparently no longer exists and when you google it, you are informed “the domain is for sale.” No, I do not wish to purchase the domain. I just wish to share my story. Anyway, for what it’s worth, here it is.

Christmas in the City

1. The Night Before

On Christmas Eve we drove down from our home by the ocean through the rain forest of eastern Connecticut, watching the sky turn to moist, violet hues as we pushed into the ambient light pollution of denser realms. Human settlements: cars and houses and shopping centers. The rain passed, we were home free, or so we thought, but somebody had reorganized the highway since our last visit and we found ourselves staring the Tappan Zee Bridge in the ominous face (“Tahpp!tap!tap-ennn-zzze bridge! De tap-tapenzee-tapenzee brih-udge!”) before choosing the desperate extremity of “last exit.” Last exit deposited us into a bedroom community where Santa tiptoed on cat paws, but no one either of us knew had ever ventured. “Duxley,” I marveled. “Ever hear of Duxley?”

It was a magical place. It had mansions concealed behind big wrought iron fences where old Dutch planters lingered in great halls, coaxing visions of sugarplum faeries from their meerschaum pipes. My wife was driving.

“Which way now?” she demanded.

“Right,” I said, nobly assuming my take-charge persona.

We took a right and then another right, passing through shiny black streets between picturesque brick buildings wherein elegant homesteaders kept to themselves. No one on the streets; lighted fir trees glowing conically from the tiny town triangles; occasional non-conformists blowing off the town zoning code by lighting up their lives in full spectrum displays which revealed more wattage than taste, but were nevertheless oddly comforting.

“At least they’re not all rich buggers around here,” she said.

“Burghers,” I corrected.

She sighed and said she knew I was hungry but could I please try to keep my mind off food?

We passed a sign saying we were entering another town we had never heard of – Neering? was this really the outskirts of the metropolis? – but magic was abroad that night (or else we just lucky and nobody else was on the road), it was Christmas Eve, and I knew it would be all right because we were heading south.

“That’s your road,” I said. “Turn left.”

“That?”

I had to admit it didn’t look like much. It looked like somebody had tried toconnect two things that shared a name but did not want tohave anything to do with each other, like Murray Amsterdam and Old New York. One went along a narrow river, over some rickety bridges, skirting ancient stoplights and abandoned mills, and somehow landed in a major city. That was the road we wanted. The other dribbled along through make-believe bedroom suburbias where people who ought to know better kept believing that Santa was just around the corner, like the Republican faith in supply side economics, and I suppose it was better than not believing in anything. That was the road we were on.

I told her toturn left where the pavement looked too narrow and she did, and we traveled between hammer and anvil, passing under a drawbridge that carried lost souls toanother century, and found ourselves with a “yield” sign and a too-short approach tothe road we had always wanted before the Tap-tap-tappan Zee Bridge stared us down.

She is driving because I cannot stand the traffic, or even the possibility of finding myself trapped in traffic, in the greater metropolitan area. I have confessed this to a psychiatrist.

“Don’t yield,” I advised, “keep going,” thinking never, never yield; and one road led to another, and one thing led toanother. And our river became a sea.

Sharon’s parents stand at the door. They say we’ve made good time.

2. Christmas at the Gershams

“We came up with a double play,” said Grace, Sharon’s mother, not on Christmas Day actually, but a couple of days later. “The botanical gardens in the morning. Then we can come back and have lunch and then go to the Met in the afternoon.” She hesitated just a second. “Because it’s open late today.”

Not “double play,” I corrected. A double play gets two outs at once and, if you are the team at bat, it is a bad thing. Double-header? Linguistic analysis doesn’t get you very far with the Gershams.

Open late? I thought, registering the second part of this announcement. An ecumenical indulgence: all things were now possible.

“The only problem is that there isn’t any morning,” Sharonpointed out.

We have got the day off to our usual unhurried start, gathering around the breakfast table at around eleven to stare at the Times, make coffee and debate waking our son.

“Morning is almost over,” Sharonobserved, rightly.

“That’s all right. The museum is open verylate.”

The Gershams are tolerant of Christmas, though Sharon, in her core values, hates it. Unlike politicians, Sharon has no problem finding her core values: she hates the rush, the hype, the commercialism, the fact that no one is at their desk or can be expected toaccomplish anything for a month, and that all important decisions must be put off until “after the holidays.” What “holidays?” she demands. We are not talking Ramadan, witches’ solstice, kookie Kwanzaa or heaven forbid, Hannukah (which even Jews cannot agree on how tospell). We are talking Christmas.

She hates the December Dilemma. We have solved the so-called, over-hyped bi-religious dilemma by putting the Hannukah candles in one room and the sacrificial tree, symbolical axis mundi of the pagan solstice festival, in the other room. The kids get twice as many presents. We eat latkes on the first night of Hannukah, seasoned with a little blood via hand-grating the potatoes. We exchange Christmas presents some evening, or morning (never on Dec. 25), when it’s convenient, given our traveling schedule. We travel to nostalgic New York tospend the day of days with my parents in the house where I grew up and seem unable to get away from, at least far enough to have an excuse not to go there for Christmas. Then we drive to the Bronx, tosee Sharon’s parents and watch a video treatment of “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” which is exempted from Sharon’s core values because it goes beyond charming and warm-and-wonderful nostalgic tonon-denominationally entertaining.

It is part of the cycle of life, one of the eternal verities. New York for the holidays.

Unfortunately everyone else is there too. Another of the verities is that you do not go toa prominent cultural institution or famous New York tourist site during the Christmas week. There you are, a kid in a candy store: the Met, MOMA, the Museumof Natural History, Rockefeller center at your feet, which get tired at the thought of these places, but you cannot go to any of these signature Manhattaninstitutions because they are mobbed. Or they have been closed to the public for shooting Woody Allen films.

But today, though it is only two days after Christmas, and a Saturday to boot, Sharon’s mother proposes we go the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Though only after going to the botanical gardens first to see the model train village, decorated with the natural products of the abundant botanical outdoors, which has been erected in honor of – the holidays? Christmas. When we arrive there, early for us (but no longer morning), cars are being directed to park on a nearby college campus. After a healthy hike around the outdoor gardens in the unseasonably balmy weather, Sharon’s parents nearly expire on the confused trek tothe cafeteria situated on the far side of some child-mobbed attractions. We never see the ballyhooed model train village; and on our way out, the line to enter the conservatory building where one may see the ballyhooed model train village is so long that Sharon has to be forcibly restrained from warning late-arriving victims, mostly model nuclear families with holiday-coddled children, they will die of starvation before getting inside.

I patiently explain this is nature’s way of culling the population.

“Don’t interfere,” I say. “It’s natural selection.”

Sharon’s parents have sufficiently recovered from their near-death experience while searching for a nice cup of tea and a soft roll to insist on driving us downtown tothe museum. Which we should keep in mind has a famous Christmas tree in the lobby. Her father, Max, drives, a thing I do not volunteer to do. So far I have neglected to explain that Grace is a devoted volunteer at this august New York institution and has succeeded in convincing us that the Met – with its broad Fifth Avenue stone stairway meeting place and Central Park for its backyard – is the true spiritual center of New York City. Forget the shopping and the tree in Rockefeller Center, the tall buildings and the Disneyfied Times Square – though she would like to take us toall those places too. The museum is the sacred place. And after volunteering all these years, it’s not just cultural homage, she actually knows the schedule – it really is open late, I am pleasantly surprised to discover, which is good because the sun is setting by the time we get there.

Because our tolerant, open-minded college student son is with us, we trek upstairs, leaving the Greeks, the Egyptians and even the Impressionists in our dust, tovisit the worst art in the place, or possibly in many places – contemporary, abstract, mid-century. Jackson Pollack seems tome richly composed and painstaking executed compared tothe gaudy-line-of-color-on-otherwise-blank-canvass school that fills this collection. The twentieth may have been my century, but this is not my art.

Being who we are, we once again hone in on the cafeteria (practically deserted compared to the trampled botanical gardens) and feast on red meat in the early winter darkness. Leaving for home when the guards start showing us the door – “it’s not thatlate,” Grace protests – the Christmas week traffic parts on the way home like the Red Sea and we drive underneath the vaulting, brightly lit transportation cathedral of the George Washington Bridge. (“George-George-Washington Bridge! The George-Washington-Washington Bridge!”)

The house is quiet, seasonal, and reasonably overheated when we arrive. We open a window, because it is late December. My son takes a telephone and disappears. We pick and choose among Grace’s collection of favorite “holiday” videos, an expansive category that includes “Candide” and “The Mikado” because we always watch them this time of year.

I meditate on Christmases past and the other branch of the journey.

3. The Day of Days

My father got an LL Bean flannel shirt every Christmas. He unwrapped the gift box slowly, with inordinate care, as if topreserve the paper for reuse, though Mom was sure totumble it into a black plastic garbage bag as soon as we had finished. Sometimes before we were finished. At last Dad would get down to the box itself, and if he were lucky, and things fell out the way he wanted, no one would be watching when he opened togaze upon the treasure within. Then he would not have toreact – “very nice, dear” – to the less than monumental experience of discovering his Christmas shirt. Was it blue this year? Or some kind of plaid? Instead of reacting (“very nice, dear”), he could carefully replace the box cover and at some well-chosen moment softly murmur “Thank you, dear, very nice” in the direction of my mother. Who of course would not hear a word of it, on account of being hard of hearing, or even if she did hear, would likely fail toassociate these few murmured words in response toher present: the new, soft, warm winter shirt, since so many minutes had gone by since it had been deposited in his lap by the youngest person in the family that particular Christmas late morning. Then, realizing something had happened, perhaps not what she thought had intended, she would deliver up her confusion by way of expostulation – “Yes, that’s right! Your present, Al! Now I see!” – and so in the end my father would be compelled to thank his wife once more for the gift she had given him (“very nice…”) and which he had so painstakingly unwrapped, and thereby attract tohimself precisely the general attention he had sought toavoid.

“Well Dad,” my sister, the baby of the family, would ask, “what do you think of your shirt?”

Some Christmases, if he were feeling well, he would venture a little bit beyond the correct, minimalist response; saying, perhaps, “I will wear it to Jim’s house later.” Then, if no one had said anything or if there were no grandchild in the house tooverride the silence, he might add the humorously intended, though slightly labored observation “I can always use something warm over there” – a reference to the widespread tendency of the old to feel cold in the homes of their energy-saving children.

And now that I have done what is right and proper, Dad seemed to say, now that I have played my part, surely I may be excused from the hurly-burly of Christmas morning at the Smallwoods’, Christmas at 45 Mere Street, and return tothat solitary pursuit of happiness that went by the name of “relaxing.” The term deconstructed from too much use. Didn’t one, one wondered, have to“relax” from or after something? Muscles relaxed from contraction. From what internal contractions Dad relaxed we will never know. “He took his secrets with him,” Sharon said.

Truth is, Christmas at the Smallwoods had gone downhill in the last few years. A few poor, pro-forma decorative touches. My father skipping meals to lair up in the backroom, looking like the wolfman. My mother nearly forgetting the helpless faded ritual of the present exchange.

How could you tell Christmas from any other day?

Every Christmas my father got a new flannel LL Bean shirt. I know – by touch, by warmth, by the cigarette burn-hole just below the collar. I own his shirt collection now.

4. Five Gold Rings

We are breaking the string this year, like an old garland of popcorn and cranberries strung by needle on a doubled thread. Actually, doubled threads are hard to break. But we are not going to my parents’ house this Christmas, because they don’t live there any more. Dad of course doesn’t live anywhere, except in my shirts.

My mother moved to the Heartland House after he died, and her house was sold just this month. I drove by on Christmas morning, taking a broad, ceremonial, largely unnecessary sweep through Nassau Countyjust to pass through the old neighborhood. No Midnight Mass this year. No need topack church-going dress-up clothes in the garment bag. No slightly embarrassing Christmas Eve drop-in at my mother’s old church, which has acquired a Caribbean persona: black faces, bright hats, sweet singing all in the choir. Even a CaribbeanEpiscopal minister in the last few years, his slow, serious demeanor matched by a bracing social awareness. If he misses my mother this year – he had visited her at home, after all, bringing the body of Christ (a phrase that has a Hitchcockian ring) – he will probably assume she has died. No, just went to heaven at the Hartland House.

Someone else is living at 45 Mere Street, and I hope they’ve moved in for their first Christmas. I see myself pulling off the familiar highway exit on the Christmas morning sweep from the Gershams’ townhouse in the Bronxout to Mom’s new place; just dropping the reigns and letting the car nose its way home to the old, overcrowded garage. “Who you folks?” we’d say. “The Johnsons? Just wanted to take a peek at the old place, see what kind of shape it’s in. Make sure you folks are taking care of it.”

“Taking care of it? We’ve only been here a month!… Listen, stranger, things have changed around these parts, and you better get used to it.”

Yeah, get used to it. But it feels funny, doesn’t it, waking up somewhere else on Christmas morning, after all these years? I resist the temptation, though the car starts topull toward the exit under the weight of habit, and continue on the familiar Southern Parkway route out East, as we islanders (Long, that is) say, to my mother’s new digs.

The sun is shining; it’s too warm for Christmas. We find Mom working on carol-sing preparation on the shiny black piano in the lounge of the spanking new, quality-controlled Hartland House, where old ladies with nice pensions nearly go to heaven. Not just ladies; there are at least two men in the place, and so my brother has taken the sensible precaution of securing power of attorney over Mom’s assets.

It is good to see Mom playing the piano, plugging away by memory, which in some respects is not so hot, especially given the long-term decline of her hearing and the recent precipitous deterioration of her sight. We are depending on her toplay for the family carol sing, which has come torepresent the single, remaining old-gang family moment of Christmas-tide. We do not pin up our stockings. Mom and Dad got rid of the tree, the mess and bother of the real tree years ago, decades ago, dad got too weak to decorate, Mom devoted her attention to patrolling the carpet for crumbs with myopic certitude, the turkey feast got transferred whole hog tomy brother’s house (along with the bubble-lights from 1957), Mom gave up shopping, my own kids grew up beyond the ga-ga-eye stage on Christmas morning, which they never really were since we exchanged presents on any day but December 25. Finally, Sharon and I gave up shopping, so that the names on my Christmas list have lately had to be satisfied by knowing they have virtuously donated some useful fragment of a domestic animal to a chosen quarter of the Third World via the Heifer Project. Dad got his LL Bean shirt. At this rate we’ll be banging on the doors of McDonald’s in a year or two.

But at least we can still sing “Jingle Bells” together so long as some of Mom’s parts work well enough tofind the keys. And then the apex of family togetherness: “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

We have bundled Mom over to my brother’s, the master of the hall, he and Helene have fed the lot of us, we have forgotten to exchange presents (checks for their kids; animal parts for Tim and Helene), and cousin Calvin, the stand-up Pavarotti of the old family crowd, is giving out parts. “You’re number one.” He points: first victim. “You’re two. Three. Four. You’re five --.”

“I’ll be five,” my son, the ordinarily agreeable toa fault, soft-spoken Marshall, home for his first college-break Christmas, interrupts.

The pause. The stare. “All right, if somebody’s going tointerrupt and confuse everything, I’ll have tostart all over. You’re one.” Points: Brenda, our twelve-year-old niece, possessor of a brand-new laptop (whatever happened to old-fashioned preteen presents like VCR’s and Nintendo?), lured away from the screen for a warm family moment by an escalating series of parental threats. “You’re two”: at Marshall.

“No, I’ll be five.”

Five, I thought: five gold rings. Why did he want them?

The stare. The pause. “Okay, I want everybody topay attention one more time. This is the toughest crowd to get in line.” Numbers; points. “You’re one, you’re two. Three. Four.” He whirls and points to soft-spoken Marshall: “You’re five.”

“Sure.”

When everyone has their number, Mom hits the keys, beginning with an elaborate instrumental introduction which confuses everyone so none of the singers know when to begin. We start over. Number one Brenda, smoked out intoadolescent self-consciousness, whispers through the first day. “On the second day of Christmas, my true love gave to me--” Brenda’s mother Helene, the most organized homemaker in Suffolk County, freezes: “—I don’t know what.”

Group laugh.

“I want everyone paying attention this time,” Calvin pronounces. “Got that Helene? You listening?”

“Two turtle doves!”

“Not now! Not now! Wait till your number comes.”

“I’m just showing you I know it.”

“Does everybody know their number?” Assents. “Diane!” That’s my mother. “Diane!” Mom hits the intro. “Skip the intro!”

We sing. Everyone knows their number. Everyone sings, Brenda so inaudibly that my mother pipes up in her fine ancient soprano, as if clueing the singer, everyone else perfectly tuneless. “Fie—ive go—old ringgggs,” Marshall offers, with perfectly respectable timing, but no special flourishes. When we get toseven swans a-swimming I make exaggerated breast-stroke motions, having played this number before. I remain the only performance artist. No lords leap. No ladies dance uninhibitedly across the floor. No hen lays an egg. But we build satisfactorily through the days, clapping and cheering each other at the end.

“Through the years,” Calvin croons, when the others have left the piano, “we all will be together, if the fates allow…”

Later I ask Marshallwhy he wanted the five gold rings. “It was grandpa’s number,” he told me. Yes, once, I remember, years ago, my father had sung the “Twelve Days” with us on Christmas Day. I had forgotten that – a homage, then. Once upon a time Dad had clapped his hands together and howled when my mother played “Deep in the heart of Texas!” at a company sing. It is hard to remember a time when he had that much energy.

Marshall and I go downstairs to play a lengthy set of Ping-Pong. He beats the crap out of me.

5. I Can Hardly Wait

Somehow the holiday, the day of days, the seasonal mood, the generalized promise of peace and benediction for all, still meant something for me. It was hard to explain even tomyself – what did one wait for? look forward to? look back on? – but as the years went on (and I went with them, whitening my beard in the winter frosts), I turned increasingly tomy own private musical celebration of the season, playing the same recordings year after year. I have frankly elitist tastes in music. I have classy, not to say classical recordings, elegant renditions – the kind of music I suspect you would hear inside the great halls of toney bedroom communities like Duxley if the owners would throw open the doors and let you peek inside, arriving like anachronistic wassailers motoring from highway exit to exit (but they won’t; they’re private). Not the same old drearily familiar songs in their predictable department store arrangements. But my songs, my music, and the quiet moments I spend listening to them have come to constitute my private celebration of the season.

It is hard to put a name on the emotion, the feelings these songs give rise to, yet I know it at once. Take a quiet instrumental, for instance “Of the father’s love begotten,” but it could be any number of others. The mood is slow, sad, even somber, as good music often is, but not deflating. I lean into the sadness and rise above any sort of heaviness or depression. I grow melancholy, perhaps, in the old poetic, paradoxical sense: a pleasant melancholy. And how can I account for the peculiar warmth aroused by such music? A palpably familiar emotion associated with nostalgia and childhood – undoubtedly; but how, exactly? I cannot avoid connecting the season’s sentimental journey with some no longer precisely remembered “warm and wonderful” Christmas back at 45 Mere Street. But when? What did it consist of? What are the particulars?

Alas, just when I am at the point of uncovering the secrets of that warm and wonderful childhood, “Of the father’s love begotten” (or something just as good) concludes and I am left stranded, with no ship of dreams to take me home. To sustain the mood, I must get up and start the recording over again. It is like kicking the choirmaster or goading the minister with a hairpin toget the service going again. The recording begins with an instrumental version of a traditional English carol, very Victorian and un-department store-like; then comes another instrumental, a classical melody. It takes a moment to place it – ah, Bach. This is far from the music of 45 Mere Street; so why does it stimulate original emotions? This is the music of the ocean kingdom where I have spent my middle years presiding like Prospero over the magical childhood I have imagined for my own offspring. So I am making up for myself a sentimental adulthood? A warm and wonderful private world. My own back room? My relaxation?

A love-tense female voice tears through the deep wood of my pleasant melancholy, taking me off guard as she does each year. “I have not forgotten,” she sings – begs – prophesies, that little Christmas yet…” But I have, in the absence of such reminders, nearly all of it: desire, romance, jealousy, youth, anticipation, soul-splitting disappointment… until the straining woman’s voice brings it back. Time will come and go, seasons lengthen and diminish. Time will fly, disappear, flee like the titmouse from the feeder, the paper-thin bones of memory snapped in the scythe of the falcon’s beak. I will not remember one thing that happened in this life, but I will remember that – I will still feel that.

Longing is better than having, it keeps hope alive. When we play old music, we bring back old longings. We hope, we anticipate. We dream. Our Christmas is a dream of Christmas.

So also – though now we have advanced to some calmer, more whimsical track – dreams the man with department store dreams. He goes home toabominable schlock-happy Christmas-whitey albums. Which presumably do for their listeners what mine do for me. This is sacred time.

Remember, something tells me, shouting in the wind, though I know I will fail.

6. All the World Should be Taxed

Marshall’s college chorus performed “In the Bleak Midwinter” along with the main event Vivaldi “Gloria” for its gala holiday concert, which given his college’s schedule, took place some time in November.

The day after Christmas he sits down at the shiny piano in the lobby of the Hartland House, noodling, while we wait to go to Boxing Day luncheon. His grandmother is upstairs, remembering or forgetting various pieces of outerwear. We have stayed over – not at 45 Mere; Grandma doesn’t live there any more – but at my brother’s in order to arrange this outing. I keep trying to build in an exercise quotient. First, we’ll go walk around the lake. Or, we’ll go to the town where the restaurant is and walk around there first. In the end, Sharon and I walk the empty sidewalks of Smithtownwhile Mom declines the exercise quotient for a variety of delicately balanced factors. Going outdoors will be enough exercise.

Waiting, Marshall rifles the pages of my mother’s sheet music, finds the score for “Bleak Midwinter” and lets out a little whoop of pleasure. “I know this one,” he says. Me too. I’ve sung it in the Midnight Masses at my mother’s church, “…in the bleak midwinter/ many years ago.”

Canonized in a literary sense, Christina Rosetti peers through the eye-holes of her pre-Raphaelite mask and seduces us with conventional topos and cow-piss sentimentality: the pan-mammalian nativity dream we learned in Sunday school, before going home toour Sunday roast.

“Heaven can not hold him/,” we sing: “Or the earth sustain/ Heaven and earth shall welcome him/ When he comes to reign.”

Singing, I embrace the orthodox sentimentality of Rosetti’s lines, even though her story/song is really just the little bummer boy, rumpa-dumb-dumb, with fine writing. It’s Amahl and the night-kitsch visitors. Amahl! Wottsmatta’ yew! What are all those people doing in the garage?

In Rosetti’s synthesis of New Testament gospel and Northern European climate – no bleak-midwinter, after all, in the Roman province of Palestine – various worshipers have come to bring their gifts to the baby Jesus, having somehow figured out – whether simple shepherd or Wisemen of Asia – that this is the real deal. Against this miraculous backdrop, the “Bleak Midwinter” singer worries the old conundrum of the poor man’s gift:

“What then shall I give him, poor as I am/ If I were a shepherd, I would give a lamb/. If I were a wise man, I would do my part./ What I can I give him/ I will give my heart.”

The wisemen were magi, I think, murmuring the reverential lyrics while Marshall picks out the tune, sorcerers and astrologers and Zoroastrians. It was a crazy sort of monotheism. It sent them hot-footing across the desert, following the signs. I wonder which religion, cults, or legend the gospels (or at least one of them) got this bit from. It makes question whether Christ is a Capricorn or Sagittarius.

7. Twelve Days of Christmas

We are packing for home. It’s hard toimagine things having gone much better. The sun is shining again. I am not insomniac or flu-ridden. The Gershams have hosted and shepherded us, Max got us in and out of Manhattanwithout difficulty, Grace got toshow off her beloved museum, and at the end of a long day no one is snapping at anyone. We have traveled miles and miles through metro-country without getting lost – except for the time they threw us off the road in Duxley. Since then we have trotted back and forth across the dense shopping country of Long Island and intervening boroughs to go from the Bronx to Smithtown and back again, pausing each time to endure the horrible traffic on the Southern Parkway near my folks’ old house – a stubborn, pointless homage to the old homestead I can’t seem to avoid. It was a cruel irony that Dad, no fan of automotive transportation in his latter days, found himself living next toone of the worst permanent traffic jams in the metropolitan area. He must be rolling over to see me seek it out. Traffic slowed but did not defeat us on the western transit back to the Gershams while a spectacularly frigid pink and orange sunset gilded the flatlands of western Suffolk Countyin one of the greatest religious displays I have ever experienced in holiday or any other time on that ordinarily unappealing slab of glacial outwash.

Arriving after dark in Riverdale, we made a rushed sortie on a Westchester Countymovie theater. I plunged intoshopping center parking-grab maneuvers best left unremembered, climaxing in an expletive which drew from my wife one of her memorable recourses to basic values:

“Don’t say fuck in front of my father.”

“Sorry dear.”

Equanimity restored, one thing leads to another, and now it is the good morrow. The car is packed, the sun is shining. We have been gifted with a new CD from my sister and her husband, a kind of contemporary sacred music composition – real voices, real string section, but also real synthesizer – and I am looking forward to popping it in for the ride home. Christmas does not end on the arbitrary date chosen by the major western religions for the feast of the nativity. At the very least, by the old folkways, you get twelve days. None of this clean up your loot and throw the tree out on the curb, with a few pathetic strands of tinsel waving forlornly above the dog doo. Oh no, I will play the old songs once more, alone at night in the mid-winter silence. The music does not stop because a page has been torn from the calendar.

I pop the new recording into the machine, uplifted by these wholesome seasonal meditations, and begin backing the car out of the in-laws’ underground garage in my patented one-finger style when a loud, sick, cracking sound announces a premature end tomy revels. It’s the sound of a fender hitting a cement post, a slap upside the head from concrete reality.

I know in my heart I deserve it.

8. “Walking in the Air”

Darkness falls early, but a little later this month than last. The holidays are over. The solstice has been survived and the sun appears tobe cycling back as scheduled. We have lit beseeching candles. We have burned our trees in rubbish piles. We used toburn our dead in what the pagans called balefires. I am not supposed to be listening tothis music any more – I have gift CDs from Christmas (Tchaikovsky, Puccini) I haven’t even opened yet –

But I am. George Winston’s subtle fingers have found their way into my evenings, and will not let go.

Now there is a slow assembly of piano keys. Single notes, one after another. Even when they are over, and their vibrations are over, they hang in the air. How does that happen? How does the connection between one note, one heard interval, maintain itself – where? in the mind? – while the next comes into existence. Rings, struck, vibrates; hangs in the air, the ether, the dimensionless instant when perception takes place; then it too passes and yet remains behind, alive as well as past; a long string of such moments; a growing string, quickening – ding! ding! ding! A bell-like string of hammer-struck strings lives in the place where sound goes (the mind?) and communicates its sense to the place where mind feels (the heart?). Hands, fingers, ears, mind, heart. They dance, they walk, they endure – in air.

After a certain age – fifty, say – everything is gravy. How long are you supposed to go on walking through time, stuffed as you are in a decaying container of hurt-able, hurting flesh? Someday you will leave it behind.

And then you will be – as I am – as angels are – as music is – walking in the air.

December 11, 2021

The Garden of Verse: Let's Take a Different Path Through the Woods This Time, What Can Possibly Happen? "Lost Again" in December's Verse-Virtual

Here's my poem on what happens when we decide to take a little walk in a very big place, the "great" outdoors. It's one of three poems in December's Verse-Virtual that treat the pleasures and -- uh, challenges of autumn in New England... I know, the season's barely over, but I can't wait to do it again.

Lost Again

So here we are again, at the corner of twilight

and self-mystification

Lost again!

The road leads ever on, as I have read somewhere,

or perhaps everywhere,

and so we are always ‘someplace,’

but truly there is more elsewhere than I am ever prepared to accept or, as the man said,

dream in my philosophy

and, right now, in this moment of befuddlement

I am unable to be philosophical about all these ‘back,’ or upper, or, as other poets have called them, ‘far fields’lurking in this ‘neck’ of the woods,

though in present circumstances I believe it more accurate to say we have lost our way

in nature’s whole ‘upper digestive track.’

The hills we gaze upon from here are in all relevant respects

much the same as the hills we saw when we knew

where we were

(or thought we did)

and thus also believed we knew

where we were going

So now, of course, we bewail the absence of signage,

as if some protective, supervisory entity has let down its guard,

some divinity of open space, or god of preservation,

guidebook author to foolish mortals.

Two roads diverged – spun off? disappeared? – in a wood –

or, more accurately,

one of those gone-back, re-wilded, cut twice a year, beautifully tangled wild-thing meadows

to which we meaningfully drive, intending to be here now,

this time of year

in order to experience the magnificent fullness

of these extra-human playgrounds of plants and fungi –

and have faced not only similar choices of diverting pathways,

but this very division, a dozen times in the past,

this time choosing the other and that has made,

if not all,

then a less than truly edifying difference

as we stare at rooftops we had not known existed,

and take equally unknown paths that lead not into temptations,

but neither to familiar destinations –

culminating, as light begins to fade, in some significant agita in the body politic.Just ‘two paths in the woods’: that’s how it started,but someone has torn up the mental maps

and scattered the twisted remains beneath the table.

So: downhill, any whichway (witch-way?) now,

discovering hermit huts that do not appear in our previous reckoning of our universe,

places without names,

esplanades of trees wholly unmarred by human use

until, at last, the fallen world descends to a ruggedly paved road

suggesting, unmistakably, the haunts of humans,

perhaps sensible ones, though none we know.

Yet, following this clue offered by the fullness of time and Earth,

the declining day comes down to an honestly car-riven road of a night-purple hueand so we face the final existential quandary: right or left?

How will the body politic decide?

The sensible party flags down a shiny vehicle,

its elderly and (happily for us) local occupants point the way,

and so, not altogether hopelessly lost in the end,

we are but merely, temporarily, misplaced.

And in response to the query our inner taskmaster,

and disappointed life coach, inevitably poses

by means of that age-old harpy voice:

‘What have you learned from this disturbance?’

we may boldly reply,

‘At least we were together.’

To see my other two poems in this issue and samplethe work of some fifty other poets, here's the link Verse-Virtual

December 10, 2021

"House Stories," My New Collection of Linked Short Stories, Published by Adelaide Books

Here's the beginning of "Fire," the first story in my new collection of linked short stories, "House Stories," just published by Adelaide Books:

"Somehow Kirby and I end up alone in the house. It doesn't happen very often because six of us have been sharing this house for over a year, and guests, lovers, and other visitors frequently swell the population. But tonight everyone else has been recruited by Mirabai, official house friend of long standing, for a road trip to her favorite childhood beach on Long Island. Kirby, who passes on the trip because he has 'business' to take care of, mixes some pleasure into that business and fills the summer night with a crew of friends and potential customers (is there a difference?) invited to sample a recent shipment of THC pills. This turns into the kind of night that ends up with guys flopping on the living room floor, threatening to stumble around in the morning as well unless somebody eases them out the door, shrewdly deputizing the most responsible party still standing (or yawning) to drive them home... "

And that's before the fire gets going.

"House Stories" tells the story of an eventful summer in the lives of a group of young people sharing a house in the Connecticut countryside circa 1970, a period of rapid cultural transformation resembling in its upheavals what American society is going through today.

The book's first-person narrator, Jon Russell, is a recent college graduate recovering from his first, largely disastrous year as a high school English teacher. He is also looking back at his brief, too-young marriage to his high school sweetheart, which ended in divorce. While Russell is delighted at the prospect of a free summer, his world is rocked by the discovery that his eighteen-year-old girl friend is a heroin addict and has been stealing money from the house.

Rapid mood swings -- Russell's delight in his newly discovered freedom; and guilt over his failure to realize that Linnie, a former student at the school where he taught, has fallen into a dark place -- characterize all these stories. His housemates include an ex-GI drug dealer; a preppy who can't finish that last paper required to graduate from college; an aspiring artist facing the necessity of becoming a teacher at his former high school; a graduate school dropout seeking to bring her New Age food philosophy into a household of men; and a talented Ivy League music major stuck in a boring summer job.

Liberated from coffee, nicotine, animal food, and other crutches -- while increasingly prone to exploring the next psychedelic to hit the market -- Jon Russell 'says yes to life,' feels cosmically energized, reads Walt Whitman amid his own 'leaves of grass,' and sees paradise in a grain of sand. He is also determined to save his teenaged girl friend from the clutches of heroin.

What could possibly go wrong?

The book is available from Adelaide Books. And also from Amazon.

You can check it out at either of these links Adelaide Books

November 10, 2021

The Garden of Verse (and Family): A Poem of My Father's Fortunate Escape, and My Own Good Reason to Stay the Course

Where do the days go? They disappear pretty fast after we play with the clock once again, threading the darkness deeper into our lives.

This month Verse-Virtual features a poem, called "Documentary Evidence," remembering my father's escape from a perilous crossing of the English Channel as his regiment was being transported to the front in France. Some of you have heard this story from me. What's new -- for me -- is the story's confirmation by a TV documentary on the subject of this disaster. I will post the poem below.

Documentary Evidence

On some channel I never watch I catch the Veterans Day doc in its last moments,

and pounce on the name of the transport ship,

snatching at details,

fleetingly like the taunt of the witch in the old story

I can never quite get enough of –

The Leopoldville! –

and lose the thread at once.

It sinks beneath the waters of my short-term whirlpool memory,

as the doomed vessel itself sends a thousand souls

scurrying for their lives, finding instead (many of them) cold water, last breaths.

The transport, that one of three,

that took the final bullet from the then death-spiraling

U-Boat reign of terror

that had plagued for half a decade the English Channel’s thin ribbon of liberation.

My father’s regiment divided among three ships,

Dad catching one of the luckier transports:

an entire line of ancestry.com, a generation’s destiny,

hanging on that chance

… And here before my tired eyes,

while stretching in front of the TV,

surfing while supine,

the documentary evidence confirming a family’s brush-with-fate survival story,

I recollect Dad recounting, a half century later,

his fortunate escape from a plunge into all that cold water,

and picture again the breadwinner who clung to the sandy shore in socks and shoes

while his children squirmed in the foam like fish.

Dad’s brush with destiny, confirmed on the screen:

Survivors as we are, not heroes,

I stick to my own fortunate course,

grateful for the lucky draw.

I have two other poems in the November issue. One, titled "Urban Transplant," one of my garden poems,takes off from my ongoing struggle to make the "sidewalk strip" in front of our house bloom like an urban Eden. I've got a ways to go.

The last poem, "Softer Stay," is about the subtle beautyof that descent into winter.

To see those go to verse-virtual november

October 14, 2021

The Garden of Verse: Years Ago I Sent a Very Short Story to "The Dawntreader" -- Now This Journal Is Publishing My Poem

A long time ago I sent a short prose piece about a man who encounters an owl in the woods to a then-new journal called "The Dawntreader." It was an excerpt really, an out-take from a draft of a novel... I sent it to this magazine because it was seeking work on "landscape, myth, nature, legend, spirituality and love / concern for the environment." Well, I thought, I'm all for that.

A year ago I came across a mention of the journal, and its publisher Indigo Dreams, on a list of publications and saw that the journal was still interested in publishing nature poems. Well, I thought, I have some of those.

"The Dawntreader" published one of my poems in July and now, in its latest issue, it has published another poem. This one is titled "Deer Uprising."

Because the journal publishes on paper, but not online, I cannot include a link to the poem here. Instead, I am posting it on this blog.

Deer Uprising

From the weedland of the fence line brush

where she has waited,

how many hours?

without betrayal to human eyes,

she flows across a strip of ground-tight wintry grass

-- exposed for mere heartbeats

during which non-predatory eyes,

the world's voyeur, happen to be staring,

(this of all moments!) --

to the old wire fence

belonging, we suspect,

to the sheep farmer neighbor,

leaps over, as if lifted by the nimble strings

of the Showman Behind the Scenes,

all laws of gravity suspended for this signature performance

-- a weightless flight that lingers in the eye --

lands, already streaming, bounding, sky-walking --

the eye cannot follow --

across the winter-dried yellow-grass,

a tone just lighter than fawn,

of that sheep-less field,

becoming one with the unpeopled land,

the weathered grass, product of countless generations,

leaves of flesh, and fleshly leavings,

as which of us shall not?

P.S. Here is some of what The Dawntreader has to say about itself (quoted from the publisher's website:

WRITERS GUIDELINES.

All submissions should follow The Dawntreader theme of the mystic,

landscape, myth, nature, legend, spirituality and love / concern for the

environment. Poetry / Prose / Articles / Legend welcomed...

Submissions should preferably be made by email using

typeface as above to avoid distortion. Short comments on previous

issue contents are very welcome.

The Dawntreader does not receive any grant or financial support from

outside sources and is solely dependent on subscriptions and donations

from well-wishers. Please spread the word.

September 17, 2021

Garden of Verse: "Traveling to Winter" in the Scissortail Quarterly

The Scissortail Quarterly, a new attractively produced English poetry journal, has three of my poems in its August issue. This is their issue No. 4. Editor Brian Fuchs also published three poems of mine in his previous issue back in March. This is getting to be a habit!

Because the journal publishes in paper, but not online, I cannot include a link to the poems here. Instead, I am posting one of the poems in the latest issue, "Traveling to Winter," here. It may be a little early to start worrying about winter, but, hey, like everything else it will be here sooner than you think. Here's the poem:

Traveling to Winter

So much darkness to contend with

Though lights appear in the lengthening night,

still the winds blow like the trumpet of a distant foe

And the ice makes for a scrabble

Not even the trashcan stands upright

I rescue it in the morning:

A half-drowned swimmer, gasping on its side

Are we all not merely a strong blow away

from some permanent stranding?

We watch weak vessels beat out to sea

Familiar figures disappear, like road signs gagged by snow

We look to the hungry ocean

Can we even wave goodbye?

Too late!

“Farewell!” we shout, “Good luck on the further shore!”

but we know they can’t hear us.

We turn about. Count heads. Anyone else missing?

We clutch each hour to our breasts

We are made of minutes

We dress in our heaviest apparel

Geer up, check provisions – call ahead

Trace the route on the map

Walk about the sled slowly, checking the tires

Did the roadmen cheat us,

their features oiled by Turner and time

The dogs howl

The clouds make faces

Babies cry behind doors closed to us

I would check for ammunition,

but my firepower is in my mouth

I ask the dentist to pull out all my teeth,

but she is wise to my folly and refuses

A lengthy journey cannot be undertaken

without acknowledgment of suffering

Birds will lose a feather or two

No further elders go before me in my father’s line

I watch the smoke signals for rumors of births,

but no announcements come

Take care, mon frere, to remain on the trail

We walk it together, my shadow and I

To learn more about the Scissortail Quarterly, or purchase an issue, see their website at Scissortail Quarterly

September 15, 2021

The Garden of Verse: Verse-Virtual's September Shopping Bag Holds Mrs. P's Groceries And Many Other Treats

So many fine poems in Verse-Virtual’s September issue. Here are my comments on a few that I particularly enjoyed...

I have read with admiration previous offerings from the mind of

Robert Wexelbatt’s worldly, cynical, sharp-eyed Mrs. Podolski. Here

in “Helping Mrs. Podolski Put Away Her Groceries,” Mrs. P. reflects on the pedestrian appetites of her late husband in a voice as unromantic, perceptive, and real-world as ever:

He preferred beef to chicken or pork and

spit out my one attempt at tofu.

Well, in fairness, so did I. No take-out

but his precious pepperoni pizzas.

Would you wash off those potatoes, dear—and

just set them on the drainboard?

From her husband’s throw-back diet, Mrs. P. moves on to universal

considerations, revealing a capacity for suave and learned citations.

On skin treatments she offers Nietzsche:

The earth has a skin,/ and that skin has diseases;

one of its/ diseases is called man.

Poetic voice is what we admire in Sylvia Cavanaugh’s lovely poem

“Gift Shoes from Philadelphia,” as in these lines:

As a child I had no idea

shoes even came in green,

or that love could take the form

of gift shoes from Philadelphia.

The implicit nostalgia for an early awakening, invented or not,

flowers fantastically in the verses to come:

Someday, a left-handed gentleman

may offer you an oyster on the half shell

in the bright afternoon

and you could become Venus…

Read on in this delightfully lyrical fantasy as those ‘gift shoes’ find

other feet.

It’s the voice again that attracts me in Arlene Gay Levine’s poem

“The Journey.” The poem begins with the existential pronouncement

of a contingent universe: “A day begins; there are no promises.”

But then we leave the known world behind:

One day we will slip from our bodies

and slide into the Light; this we know.

Perhaps to rouse from sleep and put aside

the fear that hunts our hearts…

The poem takes off from here to pronounce what else “we know,” continuing

to treat us to an elegant use of the elevated tone.

Jefferson Carter’s “Hot Tub” flat out makes me laugh, from the first lines:I confess. We owna hot tub. Nothing ostentatious,… This confession is required, we learn, because the tub’s presumed ‘luxury’ consumption of hot water is politically incorrect in the opinion of the poet’s “tree-hugger friends.” I hug as many trees as the next guy, but I don’t think we have to go after hot tubs until we all agree to stop getting on jet airplanes. The poet contemplates his friends’ scolds, the poem tells us, until we arrive at this lovely and only slightly barbed image:

as my hands flower open,

as the steam rises like smoke

through the branches

of our invasive olive tree.

The spare, sharp-tooled voice in Jim Lewis’s “gemstone” captivates me as well. Its opening lines hammer away, carefully, precisely, at the object of the speaker’s terse observations: you are hard she saidhard headedhard heartedhard won The poem strikes me as an object lesson in the uses of economy and repetition. Bereft of punctuation and qualifiers, its strokes work efficiently toward the second-person speaker’s half-surprising conclusion. you see yourselfas common stonebut you will be the center jewelin my crown There’s a final twist at the end; I won’t spoil it here.

Equally enjoyable in a different, conversational vein is David Graham’s

“Lament for Kmart,” a knowingly tongue-in-cheek encomium for a low-end

marketer I also confess to missing. How can anyone resist a poem

that begins: “

How I used to relish wandering those broad glossy aisles/

with Walt Whitman at my side!”

What’s not to embrace under the store’s “dozen fluorescent suns”?

The down-market big box store was a simple celebration of

indiscriminate American bounty:

We grinned at T shirts/ in hefty sizes, work shirts unsullied

by designer tags.

And it concludes with another glance at Whitman’s universal embrace

of his country, as rows of unplugged TV monitors reflect the faces

of passing shoppers who become momentary screen stars:

just American faces leaning and loafing at our ease,

in vain the speeding or shyness as we starred in one

TV program after another, our show brief as a sunbeam

glinting on a passing windshield.

So many excellent poems in September’s Verse-Virtual. Find them here:

https://verse-virtual.org/poems-and-articles.html

The link Verse-Virtual Sept. 2021