David Tickner's Blog, page 18

November 7, 2022

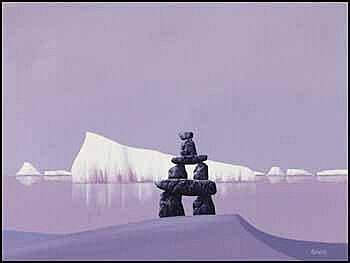

Isumataq

A few days ago, I came across the word isumataq again. I first encountered this word in the 1980s when reading Barry Lopez’s wonderful book, Arctic Dreams. At that time, I found the word particularly relevant to my college faculty development work.

A few days ago, I came across the word isumataq again. I first encountered this word in the 1980s when reading Barry Lopez’s wonderful book, Arctic Dreams. At that time, I found the word particularly relevant to my college faculty development work.In brief, isumataq, an Inuktitut word, refers to a person who creates the environment or atmosphere for a group of people in which latent wisdom can reveal itself. Inuktitut, spoken in the eastern Arctic of Canada, is one of five major Inuit languages.

What is wisdom? In brief, wisdom can be considered as a relationship to experience. Wisdom is not just what you know but how you act on the basis of what you know. Wisdom is down to earth and practical. To be wise is to act wisely.

Some synonyms for isumataq include listener, advisor, storyteller, facilitator, but not necessarily shaman or teacher.

As I think about the word isumataq again, it seems particularly relevant to the world in which we live these days, not just the world of faculty development!

To quote at length from Barry Lopez:

“And once in a great while an isumataq becomes apparent, a person who can create the atmosphere in which wisdom shows itself.

This is a timeless wisdom that survives failed human economies. It survives wars. It survives definition. It is a nameless wisdom esteemed by all people. It is understanding how to live a decent life, how to behave properly toward other people and toward the land.

It is, further, a wisdom not owned by anyone, nor about which one culture is more insightful or articulate. I could easily imagine some person … sitting with one or two Inuit men and women in a coastal village, corroborating with the existence of this human wisdom in yet another region of the world, and looking around to the mountains, the ice, the birds to see what makes it possible to put [such wisdom] into words” (298 – 299).

Looking around. Seeing. Perhaps not surprisingly the origins of the word wisdom are in ancient words meaning ‘to see’.

Image: Ken Kirkby, Inukshuk and Iceberg

https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lo...

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Lopez, B. (1986). Arctic dreams: Imagination and desire in a northern landscape. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

https://innerjourneyevents.wordpress.com/2015/03/26/just-for-today-hold-space-as-an-isumataq/

Published on November 07, 2022 11:53

November 3, 2022

Rain

The English word for rain has just about always been rain.

The English word for rain has just about always been rain.The word rain (the descent of water in drops through the atmosphere) comes from Middle English rein, Old English regn, Old Saxon regan, Old Norse regn, and Proto-Germanic regna.

Regna. Regn. Regan. Rein. Rain.

Some old rain-related words and expressions:

Old English renscur (rain shower)

Old English rendropa (raindrop)

Old English reboga (rainbow)

“To know enough to come in out of the rain” is from the 1590s.

“To rain cats and dogs” is from 1738.

Rain-gauge, an instrument for collecting and measuring rainfall at a given place, is from 1769.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 03, 2022 10:44

October 31, 2022

Halloween

Would you be surprised to learn that the word Hallowe'en or Halloween means ‘hallowed evening’ or ‘holy evening’?

Would you be surprised to learn that the word Hallowe'en or Halloween means ‘hallowed evening’ or ‘holy evening’?The Old English verb halgian (to hallow) means to make holy, to sanctify, to honor as holy. These words come from Proto-Germanic hailagon (holy) and Proto-Indo-European (PIE) kailo (whole, uninjured, of good omen).

The English word hallow comes from Old English haliga, halga (holy person, saint). The word even meaning eve or evening (but not Eve as a person's name--that's another story) comes from Old English aefen (end of the day; the time between sunset and darkness). Hallow + even = hallowed evening = Halloween.

Just as the word Eve is used to name the night before a holiday (e.g., Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve), All Hallow’s Eve is the night before All Saints Day, the Christian celebration of the saints of the church.

So, what does all this have to do with spirits and ghosts and the dead and so on?

Before Christianity, the ancient Celts celebrated the festival of Samhain to mark the harvest, the end of summer, and the beginning of winter. Samhain was a time of endings and beginnings. It was the Celtic New Year celebration. It was the time of a 'thin space' where the boundaries between the living and the dead blurred, a time when the spirits of the dead returned to earth—not just evil spirits but all spirits. People remembered their ancestors and the recent dead. Samhain was a time for predicting the future or, perhaps, as we might say, making new year’s resolutions.

As Christianity became predominant in post-Roman Britain it built over the pre-Christian Celtic celebrations and integrated them into Christian celebrations. Samhain became synonymous with All Hallows Eve. In particular, ‘all hallows’ means all the saints of the church.

The modern form of Halloween (parties, dressing up, playing tricks, and so on) is from 17th century Scotland. The celebration was popularized in a poem, Halloween, by Robert (Robbie) Burns, written in 1785. Halloween is a Scottish shortening of Allhallow-even, the last night of the Celtic calendar year known as Old Year’s Night.

It would seem that the ancient Samhain festival never really went away!

Also: Halloween, a painting by Bo Bartlett, in Harper’s Magazine, October 2022, p. 13.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/history-of-halloween

Published on October 31, 2022 09:37

October 30, 2022

Boo! Trick or Treat!

Who would have thought that you can find the origins of the word boo?! Did you know that the expression ‘trick or treat’ comes from Canada?

Who would have thought that you can find the origins of the word boo?! Did you know that the expression ‘trick or treat’ comes from Canada?Boo

The word boo, from Greek boaein and Latin boare, means to cry aloud, roar, shout. The word boh, meaning to produce a loud startling sound (BOO!!), came to English in the 15th century.

Boo-hoo, from the 1520s, was originally laughter or noisy weeping. Today, boo-hoo only means weeping. To deceive by trickery is from the 1590s as is the children’s game peekaboo. The verb ‘to boo’ is from 1838. Boo, as an expression of disapproval, is from 1884. Booing was common at that time among London theatre audiences and at British political events. A boo-boo, meaning a foolish mistake is from 1934. Boo-boo, a simple mistake, is from 1954.

Trick

The word trick comes from Latin tricari (to be evasive, to shuffle), from tricae (trifles, nonsense, a tangle of difficulties). Beyond this, the origins of the word are unknown. Trick, meaning a cheat, a mean ruse, came to English in the early 15th century from Old North French trique (trick, deceit, treachery, cheating).

Trick, a roguish prank, is from the 1580s. Trick, the art of doing something (e.g., a magic trick), is from the 1610s. “Trick or treat”, a children’s Hallowe’en pastime, is from 1927 in Canada.

Treat

The verb ‘to treat’, meaning to entertain with food and drink without any expense to the recipient as a compliment or kindness (or bribery), is from around 1500. The noun treat, that is, the actual food or drink or entertainment, is from the 1650s. By 1770, a treat meant anything that gives much pleasure. Note that origins of the word for the act of treating or ‘giving’ precedes the origins of the word for the actual treat or ‘gift’; that is, it is the ‘thought (or feeling) that counts’, not just the gift.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 30, 2022 10:28

October 29, 2022

Jack O'Lantern

In medieval times, people sometimes saw flickering lights appearing at night over marshy ground. I can imagine that in those days some might have found this phenomenon somewhat spooky. This light was called Jack’s lantern or jack of the lantern or jack o’lantern. Another name for this light was ‘will o’the wisp’; i.e., Will’s wisp or Will’s torch, a term from the 1660s.

In medieval times, people sometimes saw flickering lights appearing at night over marshy ground. I can imagine that in those days some might have found this phenomenon somewhat spooky. This light was called Jack’s lantern or jack of the lantern or jack o’lantern. Another name for this light was ‘will o’the wisp’; i.e., Will’s wisp or Will’s torch, a term from the 1660s.This mysterious light is now attributed to the combustion of gases from decomposing organic matter. In 1563, scientists named this natural phenomenon ignis fatuus (foolish fire).

The custom of carving jack o’lanterns from pumpkins at Halloween is believed to have originated in 19th century Ireland and Scotland. Halloween, also known as Samhain, an ancient Celtic festival, was a time when supernatural beings and the souls of the dead walked the earth (the souls of both good and evil people, I might add), a time when the boundaries between the living and the dead were more porous than at other times. A pumpkin with a carved scary face and a candle, set in a window, was a way to keep the harmful or evil spirits away from one’s home on a such a dark night.

On Halloween, 1835, the Dublin Penny Journal published a story on the Jack o’the Lantern. At that time the terms O’Lantern and McLantern were both used, a reflection of the Irish and Scottish use of pumpkins as lanterns to ward off the evil spirits.

In the 1540s, the words pompone and pumpion appear in English from Middle French pompon (melon). By the 1640s, the word pumpkin is seen in English. Pumpkin pie is from the 1650s. Pumpkin head, from 1781, refers to a person with hair cut short all around. An alternative spelling in American English, punkin, appears in 1806.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack-o%27-lantern

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ignis%20fatuus

Published on October 29, 2022 11:02

October 28, 2022

Haunt, Haunted

Do you ever think about going back to a place where you grew up or where you went to school? Do you think of going back going back to visit your old haunts? Is there a place that you never want to go back to? Haunts, that is, the places and neighbourhoods where you used to live.

Do you ever think about going back to a place where you grew up or where you went to school? Do you think of going back going back to visit your old haunts? Is there a place that you never want to go back to? Haunts, that is, the places and neighbourhoods where you used to live.The word haunt has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root tkei (to settle, dwell, be home), the source of Proto-Germanic haimaz (home) and haimatjanan (to go or bring home) and Old Norse heimta (bring home). The verb ‘to haunt’ comes to English in the early 13th century meaning to practice habitually or to busy oneself with; from Old French hanter (to visit regularly, be familiar with, indulge in). By around 1300, haunt also meant a place frequently visited.

In Middle English, haunt scole meant to attend school. Haunt also was used to mean ‘to have sexual intercourse with’—this gives another meaning to the term ‘haunted house’.

The use of haunt in reference to a ghost or spirit returning to the house where it had lived may have Proto-Germanic origins; however, if so, it was lost or buried until revived by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1590).

The contemporary meaning of haunt meaning the spirit that haunts a place or a ghost is first recorded in 1843 in African American Vernacular English.

The word haunted has evolved in meaning over the years. In the early 14th century haunted meant accustomed. By the mid-14th century it meant stirred or aroused. By the early 15th century it meant frequent. And then much-frequented (1570s), visited by ghosts (1711), and haunted house (1733).

Haunt could be said to be the spirit of a place which might explain why we like to return to our old haunts, to the places that have some good memories for us. We probably would not want to visit those ‘haunted’ places which hold negative memories.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 28, 2022 07:51

October 27, 2022

Witch

The origins of the word witch are rooted in obscurity: perhaps from Proto-Germanic wikkjaz (necromancer, one who wakes the dead), possibly from Proto-Indo-European (PIE) weg-yo, weg (to be strong, to be lively). The Online Etymological Dictionary notes a possible etymological connection between ‘witches’ and Gothic weihs (holy) and German weihan (consecrate), suggesting that “the priests of a suppressed religion [often] become magicians [or witches] to its successors or opponents.”

The origins of the word witch are rooted in obscurity: perhaps from Proto-Germanic wikkjaz (necromancer, one who wakes the dead), possibly from Proto-Indo-European (PIE) weg-yo, weg (to be strong, to be lively). The Online Etymological Dictionary notes a possible etymological connection between ‘witches’ and Gothic weihs (holy) and German weihan (consecrate), suggesting that “the priests of a suppressed religion [often] become magicians [or witches] to its successors or opponents.”Old English wiccian (to practice witchcraft) is likely from German wikken (to use witchcraft) and wicker (soothsayer). The word witchcraft is from Old English wiccecraeft.

In Old English, wicce was a female magician or sorceress, a woman supposed to have dealings with the devil or evil spirits in order to perform supernatural acts. Old English wicce is the source of the word witch.

In Old English, a wicca was a man who was a sorcerer, a wizard, or who practiced witchcraft or magic. However, by the 1560s, the word warlock was being used as the male equivalent of a witch. Over time, warlock and wizard had come to mean two different things.

The verb bewitch, from early 13th century biwicchen, meant to cast a spell on or to enchant. The original sense of the word carried implications of harm. The sense of bewitch as to fascinate or charm is from the 1520s.

Witchcraft was declared a crime in English law in 1542. Trials there peaked during the European witchcraze of the 1540s and 1660s when thousands of men and women were burned at the stake as witches or warlocks. These trials fell sharply after 1660. The last English trial, in 1717, ended in acquittal. The English Witchcraft Act was repealed 1736 (Trevor-Roper, 1990).

This use of wicca is not to be confused with the current use of the term Wicca (e.g., Pagan Studies, Paganism [briefly, the Latin word pagan originally meant a villager or someone who lived in the rural countryside—like the word heathen; i.e., a person who lived on the heath]).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witch_(word)

Trevor-Roper, H.R. (1990). The European witch-craze of the 16th and 17th centuries: A masterly study of early modern Europe in the grip of a collective psychosis. London: Penguin.

Published on October 27, 2022 09:12

October 26, 2022

Ghost

The word ghost has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gheis (excitement, amazement, fear), the source of Proto-Germanic gaistaz (in turn, the source of Old Saxon gest, Dutch geest, German Geist, all meaning spirit or ghost; in particular, the disembodied spirit of a dead person.

From these Germanic sources comes Old English gast or gaest (breath; good or bad spirit, angel, demon; person, man, human being; especially as used in the Biblical sense to mean soul, spirit, life) and Old English gaestan (to terrify).

Ghost, as an English term meaning the spirit of a dead person wandering among the living, haunting them, is from the late 14th century. Sounds ghastly.

A poltergeist (a noisy spirit or ghost which makes its presence known by noises) is from 1838, from German Poltergeist (literally, ‘noisy ghost’).

The words aghast and ghastly (terrified, filled with frightened amazement), from around 1300, are from Middle English agasten (to frighten) and Old English gaest (ghost).

In brief, the word ghost has Germanic origins. The related Latin term is spiritus (spirit).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

From these Germanic sources comes Old English gast or gaest (breath; good or bad spirit, angel, demon; person, man, human being; especially as used in the Biblical sense to mean soul, spirit, life) and Old English gaestan (to terrify).

Ghost, as an English term meaning the spirit of a dead person wandering among the living, haunting them, is from the late 14th century. Sounds ghastly.

A poltergeist (a noisy spirit or ghost which makes its presence known by noises) is from 1838, from German Poltergeist (literally, ‘noisy ghost’).

The words aghast and ghastly (terrified, filled with frightened amazement), from around 1300, are from Middle English agasten (to frighten) and Old English gaest (ghost).

In brief, the word ghost has Germanic origins. The related Latin term is spiritus (spirit).

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 26, 2022 09:44

October 25, 2022

Skeleton, Mummy

Skeleton

SkeletonSkeletons have not changed that much over the centuries in either appearance or name. The word skeleton has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root skele (to parch, wither).

The word skeleton appears in English in the 1570s from Latin sceleton (bones, bony framework of the body), Greek skeleton soma (dried-up body, mummy, skeleton) and skeletos (dried up), and Greek skellein (to dry up, make dry, parch)—all from PIE skele.

PIE skele is also the source of Greek sclerosis (hardening) and late 14th century English sclerosis (morbid hardening of tissue).

Mummy

No, we are not talking about your Mum.

Mummy comes from Persian mumiya (asphalt) and mum (wax), then Arabic mumiyah and Latin mumia, both meaning an embalmed body. The word mummie comes to English in the late 14th century meaning a medicinal substance prepared from mummy tissue. The use of mummy to mean a dead body embalmed and dried after the manner of the ancient Egyptians comes to English in the 1610s.

The verb ‘to mummify’ (to embalm and dry a dead body as a mummy) is from the 1620s. Mummification, the process of making into a mummy, is from 1793. The state or fact of being a mummy is from 1857. The use of mummify meaning to shrivel or dry up is from 1864.

What’s the connection between mummies and Hallowe’en aside from theme of death and the dead. Perhaps the connection comes from the ancient mummies found in Egyptian tombs and the curses that were said to fall on anyone who disturbed these bodies.

By the way, ‘Mom’ is American English and ‘Mum’ is British English, just in case you were wondering. But I digress.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 25, 2022 09:26

October 22, 2022

Kit, Kit Kat

The word kit, meaning a round wooden tub, first appeared in English in the late 13th century, perhaps from Middle Dutch kitte (jug, tankard, wooden container). The origins of kit and kitte are unknown.

The word kit, meaning a round wooden tub, first appeared in English in the late 13th century, perhaps from Middle Dutch kitte (jug, tankard, wooden container). The origins of kit and kitte are unknown.Gradually, the word kit shifted in meaning from the container to the stuff in the container. For example, kit meaning a soldier’s personal effects is from 1785; kit meaning a workman’s tools is from 1851. The connotation of kit as container returned with terms such as ‘kit-bag’ (1898) and ‘tool kit’ (1908).

‘Drum kit’ is from 1929. Kit, meaning an article to be assembled by the buyer, is from the 1930s; e.g., a model airplane kit.

What about the term ‘kit and caboodle’ from 1870? Caboodle may come from Dutch boedel (bundle, property). The ‘whole kit and caboodle’ means both your bag and all its contents.

‘Kitty’? The pool (or bundle) of money in a card game: from American English, 1884.

‘Kit Kat’ chocolate? In late 18th century England, kit cats were mutton pies created by a pastry chef whose name, according to some sources, was Christopher, or Kit (a short version of Christopher), Catling. These pies were very popular at what became known as the Kit Cat (or Kit Kat) Club, the home of the Whig (liberal) political party of the time. The Rowntree family, members of the Club, trademarked the name in 1911 for one of their chocolate products. In 1937, the chocolate confection now known as Kit Kat was introduced.

Why is Kit Kat so popular in Japan? In Japanese, Kit Kat is translated as Kitto Katto which sounds like the Japanese phrase kitto katsu meaning, “You will surely win!” In brief, Kitto Katto represents good luck.

What about kitty-cats, kittens, and other young fur-bearing animals? That’s another story.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 22, 2022 12:00