David Tickner's Blog, page 17

December 27, 2022

Nook and Cranny

Have you ever lost or misplaced something and looked in every nook and cranny for it?

Have you ever lost or misplaced something and looked in every nook and cranny for it?Nook

The origin of the word nook is unknown. The word came to English around 1300 meaning an angle formed by the meeting of two lines; in particular, where the walls meet at the corner of a room. By the late 14th century, nook referred to a remote or secluded place. Later, a nook also referred to a small, often recessed, section of a larger room; e.g., a breakfast nook in a kitchen.

What about nookie? This is a slang term for sexual activity from the 1920s with suggested origins in Dutch neuken (to copulate with) or in the connections with secluded places. Again, the origins are uncertain if not unknown.

Cranny

The word cranny, meaning a small narrow opening or crevice came to English in the mid-15th century possibly from Old French crener (to notch, to split), Latin cernere (to separate, to sift), and the Proto-Indo-European root krei (to sieve). These origins are suggested but are uncertain.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on December 27, 2022 07:58

December 22, 2022

The holly and the ivy

Do you prefer the pub version or the choir version of the ‘Holly and Ivy’ folk song?

Do you prefer the pub version or the choir version of the ‘Holly and Ivy’ folk song?Holly

The word holly has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) kel (to prick), Proto-Germanic hulin, and Old English holegn and holen. The 12th century word holin precedes the mid-15th century word holly. Holly is an evergreen shrub long used as part of Christmas decorations.

Ivy

Ivy, a climbing plant, comes from Old English ifig. Before this the origin of the word ivy is unknown. In the mid-15th century, the image of an ivy bush was used on the signage of taverns which served wine, ivy being sacred to Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and other things (Bacchus, known as Dionysus in Greek mythology).

Holy & Ivy

In ancient times, holly was thought to be a male plant and ivy a female plant.

The ancient Romans used holly in different ways—to ornament the home as an omen of good fortune and immortality. Holly wreaths were sent to newlyweds for the same reason. And holly was used during the December Saturnalia festival. Early Christians, celebrating Christmas at this time, used holly as the spiky leaves symbolized Jesus’s crown of thrones and the red berries symbolized his blood. Harry Potter’s wand is made of holly, by the way.

Ivy, in addition to being associated with wine and intoxication as in the mythology of Bacchus and Dionysus, was also a symbol of fidelity and marriage. Ivy was wound into a crown, wreath, or garland as a symbol of prosperity and charity. As such, ivy was adopted by the early Christian church as a reminder to help the less fortunate.

The Christmas carol ‘The holly and the ivy’ is based upon ancient beliefs which were absorbed by the Christian church. The carol sung today was first recorded by Cecil Sharp, a folk song collector, who heard it sung in England in 1909.

Scroll down the following link for a couple of versions of the song: https://mainlynorfolk.info/steeleye.span/songs/thehollyandtheivy.html. I like the pub version!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://davesgarden.com/guides/articles/view/2731

Published on December 22, 2022 10:45

December 19, 2022

Egg Nog

While the origin of the term ‘egg nog’ is unknown, it likely originated in the medieval English term ‘posset’—a hot, milky, ale-like drink. In the 13th century, monks drank posset with eggs and figs.

While the origin of the term ‘egg nog’ is unknown, it likely originated in the medieval English term ‘posset’—a hot, milky, ale-like drink. In the 13th century, monks drank posset with eggs and figs.The word noggin, a word from the 1620s, meaning a small cup or mug, may be the origin of the word nog. Also at this time, nog referred to a type of strong beer brewed in Norfolk.

The term egg nog referred to a sweet, rich, and stimulating cold drink made of eggs, milk, sugar, and spirits. Old recipes suggested using beer or wine instead of milk.

By the 1670s, a ‘boull (i.e., bowl) of nog’ was something shared with friends and guests. Nog referred to the contents, not to the cup.

The American term, eggnog, is from 1775. If you are thinking of making your own eggnog, here is a recipe from that time:

One quart cream, one quart milk, one dozen tablespoons sugar, one pint brandy, 1/2 pint rye whiskey, 1/2 pint Jamaica rum, 1/4 pint sherry—mix liquor first, then separate yolks and whites of a dozen eggs, add sugar to beaten yolks, mix well. Add some milk and cream, slowly beating. Beat whites of eggs until stiff and fold slowly into mixture. Let set in cool place for several days. Taste frequently.

Enjoy!

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://time.com/3957265/history-of-eggnog/

Published on December 19, 2022 11:13

December 8, 2022

Mittens

In the mid-13th century, the English word mitain was a surname. By the late 14th century, the word mitain referred to a glove or a covering for the hand. Maybe someone in the Mitain family started a mitten business?

In the mid-13th century, the English word mitain was a surname. By the late 14th century, the word mitain referred to a glove or a covering for the hand. Maybe someone in the Mitain family started a mitten business?The word mitten has its origins in Latin medietana (divided in the middle); i.e., a hand covering divided in the middle, one side for fingers and the other side for the thumb, rather than a glove with five separate sections for fingers and thumb.

In 1825, the expression ‘to get the mitten’ referred to a woman’s refusal of a man’s amorous advances. The man was given the mitten rather than the hand.

“Whatever happened to dear Egbert?” “Oh, I gave him the mitten last weekend.”

The short version, mitt, is from 1765. The baseball mitt is from 1902.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on December 08, 2022 10:33

December 5, 2022

Craft, Crafty, Handicraft

What comes to mind when you hear the word crafty? As crafty as a fox? Sly, sneaky, secretive, cunning?

What comes to mind when you hear the word crafty? As crafty as a fox? Sly, sneaky, secretive, cunning?The word crafty appears in the mid-12th century as crafti (skillful, clever, learned), from Old English craeftig (strong, powerful, skillful, ingenious—the origin of the word engineer, by the way). Until the end of the 16th century crafty also meant skillfully done or made; intelligent, learned; artful, scientific.

The word craft has its origins in Proto-Germanic krab-/kraf- and, later, in Old English craeft (power, physical strength, might). Beyond this, the origins of the word are unknown.

The Old English meanings of the word craft also included skill, dexterity, science, talent (mental power). During the medieval period, the word craft referred to the trades, handicrafts (work produced by craftspeople), employment requiring special skill or dexterity, and something built or made. At this time, the word craft continued to be used in reference to might and power.

Consider the highly skilled craftspeople of the medieval period—the blacksmiths, goldsmiths, weavers, metal and wood workers, chefs, masons, potters, glaziers, and many others who, without so-called book learning, produced castles, ships, cathedrals, armor and weapons, textiles, jewellery, and a myriad of other common everyday and luxury items.

The verb ‘to craft’, from Old English craeftan, and meaning ‘to make skilfully’ is from the early 15th century.

However, during the medieval period, the word crafty also came to mean secretive and sneaky, scheming and devious. The verb ‘to craft’ gradually became obsolete. Why?

Why the negative connotations of craft and crafting?

People who were ‘crafty’ were sometimes perceived as being cunning and secretive. Only they knew the ‘tricks of the trade’, so to speak. “Craft knowledge was … ‘secret’ insofar as it was hidden from the understanding of those not experienced in the craft, or because its efficacy was ‘hidden’ in the things of nature or in the material objects craftspeople made. Thus … craft was perceived as powerful and potentially deceptive” (Smith, 118).

What craftspeople learned by practical experience could not be learned simply by reading books. A craftsperson needed to apprentice with a master and practice practice practice until they developed their own practical knowledge.

By the 16th century, with the printing press and the rapid dissemination of books, ‘book knowledge’ quickly gained or was given more prestige than ‘practical knowledge’. Intelligence and knowledge were understood to reside only in the head rather than in other parts of the body and bodily sensations (taste, touch, smell, and so on).1

Only in the early 1950s, did the verb ‘to craft’ return to popular usage, especially with regard to practical knowledge and skills and to current trends related to ‘making’ and ‘makerspaces’; e.g., https://www.makingandknowing.org/

The word handicraft, from Old English handcraeft (skill of the hand), is a word which has travelled a long way from its traditional meaning; i.e., from the products produced by professional artisans to the fun projects of elementary school students and other such recreational or leisure-based activities. However, handicraft is another word and another story.

1 As Sir Ken Robinson said in one of his famous TED Talks, “Typically [professors] live in their heads. … They look upon their body as a form of transport for their heads. It’s a way of getting their head to meetings!”

Robinson, Sir K. (2006). Do schools kill creativity? [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity?language=en

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Smith, Pamela H. (2022). From lived experience to the written word: Reconstructing practical knowledge in the early modern world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

David’s Wordshop Blog: http://www.davidtickner.ca/blog

www.davidtickner.ca

Published on December 05, 2022 09:24

November 28, 2022

Very

How often do you use the word ‘very’?

How often do you use the word ‘very’?It’s very chilly today. She is a very pleasant person. I had a very good dinner last night. I love her very much. That’s a very small window. He has been here for a very long time. This book is very important. I know very little about that topic. One website I checked provided 500 such sentences using very in slightly different or very different usages.

The word very came to Middle English in the late 13th century as verray (true, real, genuine) from Old French verai (true, truthful, sincere; right, just, legal) and Latin verax, veracis (truthful, veracity). The word very has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) were-o (true, trustworthy).

The word verily, meaning ‘in truth’, from the early 14th century, is also from Middle English verray.

Very, as an ‘intensifier, meaning greatly or extremely, is from the mid-15th century.

In brief, to say, “That’s very true” is like saying, “That’s truly true.”

-o-

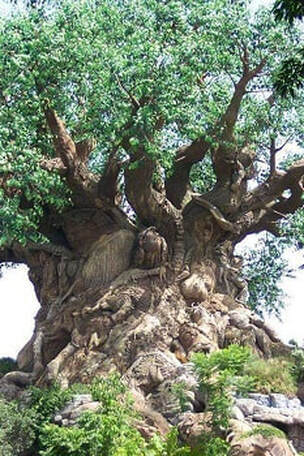

So, why the image of a tree? The words true and tree come from the very same ancient source: PIE deru (to be firm, solid, steadfast). To me, that connection provides a very illuminating insight into how the ancient Indo-Europeans thought about true and truth. Just saying…

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 28, 2022 09:06

November 25, 2022

Stakeholder

So, what does a stakeholder hold?

So, what does a stakeholder hold?The word stakeholder, from 1708, is a person with whom bets are deposited when a wager is made. By the 1960s, stakeholder also referred to a person who has something to gain or lose (e.g., in a business) or to a person who has or shares a common interest in something.

The word sweepstakes (a prize won in a race or contest), from 1773, has its origins in the Middle English word swepstake referring to a person who swept or won all the stakes in a game.

The stake in stakeholder is not to be confused with other meanings of stake: stake as a noun (e.g., a wooden stake put in the ground, stake as an amount of a wager) or the verb ‘to stake’ (e.g., to stake out a claim).

In brief, a stakeholder holds the money or an interest, not a piece of wood.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 25, 2022 15:01

November 21, 2022

Football or Soccer??

What came first? Football or soccer?

What came first? Football or soccer?Football

The word football, meaning an open-air game involving kicking a ball, is from around 1400, from 1350’s word foteballe. By the mid-1600s, football was a national obsession in England. In contrast, football was illegal in Scotland for a time in the 15th century. I don’t think that lasted very long. The rules of football were first regularized at Cambridge University in 1848.

The style of football known as rugby is from 1864, named for the English city of Rugby where the game was first played. Rugby, or rugger, is a variation of football that involves the use of hands as well as feet.

The US version of football was originally very similar to English ‘rugby football’. US football in the 19th century was known in England as “stop-start rugby with padding.” The first collegiate football game in the US, a match between Princeton and Rutgers, played on 6 November 1869, had rules much like English rugby football. However, a week later, however, the two teams played a re-match with a revised set of rules, which are much like today’s US football.

Soccer

The word soccer, from 1889, was originally socca, then socker (1891), and finally soccer (1895)—all words from university slang. The word soccer is a shortened form of the word association from the name of the Association Football organization; i.e., ass-soc-iation. One theory is that no one wanted to be known as an ‘asser’ so the abbreviation ‘soccer’ was used.

The terms soccer and football were used interchangeably in England until the 1980s. At that time, the word football became used less often to avoid confusion with US football.

In brief

The word football came before the word soccer. The words football and soccer, now used interchangeably in most of the world, describe what was originally known as English football; e.g., the FIFA World Cup of Football in Qatar. In contrast, the term football, as used in the US, is an entirely different game.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 21, 2022 11:23

November 17, 2022

Calculus

Is there a mathematician in the house?

Is there a mathematician in the house?The word calculus has its origins in Greek khalix (small pebble) and Latin calx (small stone), perhaps from the ancient use of pebbles as reckoning counters.

Calculus, as the mathematical method of treating problems by the use of a system of algebraic notation, was developed by Isaac Newton in the 1660s. Calculus is a Latin word, originally meaning a reckoning or an account.

Since 1732, the word calculus has been used in medicine to mean kidney stones and, later, any concretion occurring accidentally in an animal body; e.g., dental plaque or calculous.

Related words include a calculator (a mathematician) and a calculation, both from the late 14th century. The verb ‘to calculate’ meaning to estimate by mathematical means is from the 1560s; meaning to plan or devise is from the 1650s.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on November 17, 2022 11:28

November 14, 2022

Trauma

The noun trauma comes unchanged to English in the 1690s from Greek and Latin trauma (a physical wound, a hurt; a defeat). Trauma in ancient times meant the same as it does today—physical suffering.

The noun trauma comes unchanged to English in the 1690s from Greek and Latin trauma (a physical wound, a hurt; a defeat). Trauma in ancient times meant the same as it does today—physical suffering.The adjective traumatic, from the 1650s, is from Latin traumaticus and Greek traumatikos (pertaining to a physical wound). The verb ‘to traumatize’, in reference to physical wounds, is from 1893.

The word trauma has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) trau, from the PIE root tere- (to rub, to turn; also, related to words meaning twisting, boring, drilling, piercing; and, to the rubbing of cereal grain to remove the husks).

The use of the word trauma, used to describe a psychological condition, is relatively recent; e.g., a ‘traumatic’ experience (1889); ‘to traumatize’ (1893). Trauma, in the sense of a psychic wound or unpleasant experience which causes abnormal mental stress and resulting illness or damage to the physical body, is from 1894.

Before the word trauma came into common use, doctors working with physically wounded soldiers in the US Civil War of the 1860s used the term ‘nostalgia’ to describe forms of psychological trauma now known by terms such as shell shock, war neuroses, battle fatigue, PTSD, and so on. For example, during the Civil War doctors reported 2,588 cases of nostalgia and 13 deaths attributed to ‘nostalgia’ (https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=nostalgia).

The word nostalgia, from 1726, was first defined as the distress related to a morbid longing to return to one’s home or native country. In contrast, the word sonastalgia, coined in 2002, refers to the mental distress experienced when realizing that for whatever reasons you cannot return your home or to ‘the way things used to be’( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solastalgia). Both nostalgia and sonastalgia can be considered as forms of psychological trauma.

Another example: The American Psychological Association (APA) suggests that climate change can be a cause of trauma (https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/mental-health-climate.pdf); e.g., general anxieties about climate change or actually dealing with the specific effects of flooding, hurricanes, or other phenomena can affect a person’s physical health.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Self, W. (2021, December). A posthumous shock: How everything became trauma. Harper’s Magazine, 343 (2059), 23 – 35.

Published on November 14, 2022 20:52