Robert Munson's Blog, page 9

January 25, 2025

782AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Interfaith Dialogue

Patriarch Timothy I lived from around 740AD to 823AD. For a little over half of his life he served as Patriarch of the Church of the East (780 – 823). Supposedly, in 782 he had a discussion of religion with Caliph Al-Mahdi (reigning 775-785).

In some ways this appears to be the earliest (or at least best early) conversation between informed passionate adherents of two different faiths that is at the same time respectful.

I would recommend reading it yourself… it is not a horribly long read. CLICK HERE

The document is interesting on several fronts. Some have suggested it is fictional. Of course that is always a possibility, but that leads to the question not only of who would make it up, but (more importantly) to what end. While Islam is treated with considerable respect, Timothy gives a remarkably strong case for Christianity if it was from a Muslim writer. If it was from a Christian writer, one might expect it to be more hagiographic in terms of portraying Timothy, and frankly, the Caliph gives a pretty strong case as well for his faith. It could be argued that it was written to be read by both Christian and Muslim. However, as it is a document that ultimately was passed down through the church, it can’t be assumed to be completely ambivalent regarding religion.

To me, it seems to be some honest history. Timothy was a newly minted Patriarch of the Church of the East when there was a lot of political controversy, and while under the control of a regime that sought to be benevolent, but whose faith is competitive and has been from its roots. As such, Timothy sought to present Christianity in a positive way, while still being very respectful of the ruler and the ruler’s faith.

We see a similar thing with Francis of Assisi when he speaks to the Sultan in Cairo during the Fifth Crusade. While the aspects of this story are arguably uncertain, it seems clear that his interaction with the Sultan was respectful. An article on this can be reading CLICKING HERE.

My previous post which was based on an event just a few years before Timothy’s interaction with the Caliph expressed a different revolutionary idea. Timothy interacted with “the enemy” with reasoned word and respect, while with Charlemagne, interaction was marked by killing and forced conversion.

These two paths met in the Holy Land a little over 3 centuries. There the forces that identify themselves with Christianity fought with forces that identify themselves with Islam. In that setting, Francis and his friars cross the battle lines to wage a (non-) battle for peace with dialogue with what would generally be considered to be the enemy. The juxtaposition of these two traditions are stark in their contrast.

Of course, Timothy was not the first to talk to government leaders of a different faith. John the Baptist did, as did Paul. Some of the Apologists (like Aristides) wrote letters to the emperor to argue in support of the faith.

Still, I think it is in Timothy we see the power of the Christian faith and message when it is in a position of powerlessness.

Prayerfully, we will achieve such powerlessness again, and soon.

January 21, 2025

776AD 1st Millennium Missions History. Start of “The Cross or the Sword”?

Many years ago I read a book, “The History of Anti-Semitism” by Leon Poliakov. Actually, I only read Volume 2 because that was the only one for which I had a copy. (The book is available in digital form at http://www.archive.org.) It is rather disheartening that the topic of anti-semitism would need to have multiple volumes. In the book, Poliakov goes into a bit of an excursus on the history of violence or threat to cause religious conversion. Force conversions, or at least forced rituals, under threat has a long history (consider the case of Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego in the Book of Daniel), but Poliakov sought to focus on the case study of Christianity. He suggested that violence or threat to cause religious conversion goes back to Charlemagne of the Franks. In 776AD, for example, winning a victory over the Saxons, the vanquished were ordered to accept Christian baptism, or die.

This is not to say that violence and religion did not go together before this. Back in 312AD, Constantine, supposedly, had a vision of a Cross with the words, “By this, conquer.” In 776 AD, it was only a few years before that the Muslim invasion of Western Europe was stopped and partly turned back. Christians and Muslims were pretty happy to invade and conquer in the name of their respective faiths or their (different interpretations of) God. But in some ways it is different than forced conversions. This sort of fighting and killing is about power projection— an almost overpoweringly addictive thing for nations, cultures, AND religions. Forcing people to change religion is different, and Poliakov saw Charlemagne as starting an ugly trend that Christianity struggled to toss aside. It is hard to see how any of this is seen in the words of actions of Jesus or the early church.

But as far as I can see, Poliakov wasn’t correct— at least not correct for Christianity overall. In the Byzantine Empire, violence as a means for conversion goes back well before this.

During the reign of Emperor Zeno (474-491AD) tensions grew. According to one account, the emperor had required Samaritans to convert to Christianity. When they refused, they revolted and this led to a violent response killing tens of thousands of Samaritans. Some argue that the historical record is backward and that the revolts preceded the demand to convert. Either way, conversion was less connected with embracing the good news of Christ voluntarily, and more connected to risk of harm. Choose the cross or the sword.

During the time of Emperor Justinian during the next century an edict was established that virtually made being a member of the Samaritan faith illegal. There were a series of revolts by the Samaritans that led to violent reprisals by the government. This resulted in the Samaritan population reducing from the hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands.

The Islamic invasion actually gave some reprieve, for awhile at least, but special taxes and periodic forced conversions and killings, especially during the Abbasid Caliphate and Ottoman Empire, took their toll. By the end of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, Samaritanism reached its lowest point with just over 100 adherents.

—Robert Munson. Missions in Samaria, pages 43-44.

I hope it need not be said that this is NOT what we as Christians are called to do. I almost don’t want to put this in a history of Christian missions. Yet it is part of our history. We can (and must) learn from our history, but that only happens if we study our history.

776AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Start of “The Cross or the Sword”?

Many years ago I read a book, “The History of Anti-Semitism” by Leon Poliakov. Actually, I only read Volume 2 because that was the only one for which I had a copy. (The book is available in digital form at http://www.archive.org.) It is rather disheartening that the topic of anti-semitism would need to have multiple volumes. In the book, Poliakov goes into a bit of an excursus on the history of violence or threat to cause religious conversion. Force conversions, or at least forced rituals, under threat has a long history (consider the case of Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego in the Book of Daniel), but Poliakov sought to focus on the case study of Christianity. He suggested that violence or threat to cause religious conversion goes back to Charlemagne of the Franks. In 776AD, for example, winning a victory over the Saxons, the vanquished were ordered to accept Christian baptism, or die.

This is not to say that violence and religion did not go together before this. Back in 312AD, Constantine, supposedly, had a vision of a Cross with the words, “By this, conquer.” In 776 AD, it was only a few years before that the Muslim invasion of Western Europe was stopped and partly turned back. Christians and Muslims were pretty happy to invade and conquer in the name of their respective faiths or their (different interpretations of) God. But in some ways it is different than forced conversions. This sort of fighting and killing is about power projection— an almost overpoweringly addictive thing for nations, cultures, AND religions. Forcing people to change religion is different, and Poliakov saw Charlemagne as starting an ugly trend that Christianity struggled to toss aside. It is hard to see how any of this is seen in the words of actions of Jesus or the early church.

But as far as I can see, Poliakov wasn’t correct— at least not correct for Christianity overall. In the Byzantine Empire, violence as a means for conversion goes back well before this.

During the reign of Emperor Zeno (474-491AD) tensions grew. According to one account, the emperor had required Samaritans to convert to Christianity. When they refused, they revolted and this led to a violent response killing tens of thousands of Samaritans. Some argue that the historical record is backward and that the revolts preceded the demand to convert. Either way, conversion was less connected with embracing the good news of Christ voluntarily, and more connected to risk of harm. Choose the cross or the sword.

During the time of Emperor Justinian during the next century an edict was established that virtually made being a member of the Samaritan faith illegal. There were a series of revolts by the Samaritans that led to violent reprisals by the government. This resulted in the Samaritan population reducing from the hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands.

The Islamic invasion actually gave some reprieve, for awhile at least, but special taxes and periodic forced conversions and killings, especially during the Abbasid Caliphate and Ottoman Empire, took their toll. By the end of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, Samaritanism reached its lowest point with just over 100 adherents.

—Robert Munson. Missions in Samaria, pages 43-44.

I hope it need not be said that this is NOT what we as Christians are called to do. I almost don’t want to put this in a history of Christian missions. Yet it is part of our history. We can (and must) learn from our history, but that only happens if we study our history.

January 17, 2025

754AD 1st Millennium Missions History. Death of Boniface

In 754 AD, St. Boniface died. He was killed by Frisian robbers. I must admit that, although there is much to commend him in terms of missional fervor and even in terms of innovation (such as supporting women serving in a missionary capacity), I find him rather unlikable. The main thing is his active support of what could be called “Power Missions.’ Two examples should suffice:

#1. He actively opposed the work of Celtic Missionaries. Celtic Missions honored Rome but did not necessarily see themselves as being under the full control of Rome. For Boniface this was unacceptable. He attempted to get the pope to excommunicate them. The pope declined this. This form of missions is using “ecclesiastical power.”

#2. In reaching the Germanic pagans, he was known to use a different form of power encounter. He was well-known for chopping down the Donar Oak (Thor’s Oak). It was apparently a sacred tree to the people in the region. When their god did not strike down Boniface, they converted to Christianity. I struggle to look at this in a positive way. It is pretty awful to destroy something that someone else values. Some may say that the end justifies the means. However, one must wonder what lesson one might take from the fact that pagans killed Boniface while facing no temporal consequence.

I am probably being too negative. Most missionaries are a strange mixture of complex beliefs, motivations, and actions. For me, however, I do tend to see in him what NOT to do… at least in terms of the role of power in missions.

A few posts I have done before:

Saint Boniface, Celsus, and Power Missions

St. Boniface and the Peregrini, Part II

St. Boniface and the Peregrini, Part III

754AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Death of Boniface

In 754 AD, St. Boniface died. He was killed by Frisian robbers. I must admit that, although there is much to commend him in terms of missional fervor and even in terms of innovation (such as supporting women serving in a missionary capacity), I find him rather unlikable. The main thing is his active support of what could be called “Power Missions.’ Two examples should suffice:

#1. He actively opposed the work of Celtic Missionaries. Celtic Missions honored Rome but did not necessarily see themselves as being under the full control of Rome. For Boniface this was unacceptable. He attempted to get the pope to excommunicate them. The pope declined this. This form of missions is using “ecclesiastical power.”

#2. In reaching the Germanic pagans, he was known to use a different form of power encounter. He was well-known for chopping down the Donar Oak (Thor’s Oak). It was apparently a sacred tree to the people in the region. When their god did not strike down Boniface, they converted to Christianity. I struggle to look at this in a positive way. It is pretty awful to destroy something that someone else values. Some may say that the end justifies the means. However, one must wonder what lesson one might take from the fact that pagans killed Boniface while facing no temporal consequence.

I am probably being too negative. Most missionaries are a strange mixture of complex beliefs, motivations, and actions. For me, however, I do tend to see in him what NOT to do… at least in terms of the role of power in missions.

A few posts I have done before:

Saint Boniface, Celsus, and Power Missions

St. Boniface and the Peregrini, Part II

St. Boniface and the Peregrini, Part III

Quote on Missionary “Authority”

When we consider the missionary task, one potential danger (which happened so often during the colonial days and still happens in some areas today) is that the recipients of the gospel elevate the missionary, the missionary’s culture, or even the missionary’s theology to an exalted status. Because the missionary is often sent from a place where the church has existed for a longer time, the church in that location will have had longer to train pastors, develop seminaries, and write theologically oriented books. The easiest path for the missionary to train pastors in these situations is to say, ‘Here is what we have decided is correct theology.’

Is not teaching in this way okay, though? In some sense, yes. From a positive perspective, missionary theological educators who do so are simply passing on what the historical church has affirmed to be orthodox theology. This helps church leaders in this new context to understand and relate to the legacy entrusted to them by a ‘previous’ generation. At the same time, though, a danger exists where teachers set the standard for this new generation of church leaders that this is the only appropriate way to think. This danger exists for both informal programs that may be content heavy and formal programs that are more academic and primarily build upon Western material.

The danger may be especially real in places where missionaries are providing theological education at formal institutions. A greater power distance exists in such locations where students accord respect to teachers in such a manner that they are rarely questions. Similarly, in an honor-shame culture, students will likewise not ask questions since doing so would cause the teacher to lose face. It is as if the student is saying, ‘I need to ask this question since you didn’t explain the content claerly enough.’

-Will Brooks, “Allowing a Theology of Mission to Shape Theological Education,” in Equipping for Global Mission: Theological and Missiolocal Proposals and Case Studies. Eds. Linda P Saunders, Gregory Mathias, Edward L. Smithers. (William Carey Publishing, 2024), 76.

January 13, 2025

635AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Moving East

Christian Missions in the 4th and 5th centuries seemed to grind to a halt. If I remember right, Patrick Johnstone described this period as the “First Stagnation.” PERHAPS that is the “triple whammy” one gets from Christianity becoming a state religion.

#1. There is the temptation to see the faith as an “Ethnic Religion”— seeing it as being ‘for us’ and NOT ‘for them.’

#2. There is a tendency for surrounding nations to look unfavorably on the faith, seeing it as an ally of the enemy.

#3. Tying one’s religion to one’s political state can lead to feelings of “failure” when one’s state is in decline or overthrow. (The millennia-old belief that battling human armies are the earth-side reflection of heaven-side battles between the gods is an amazingly enduring idea.)

This period of time that surrounds the decline of the (Western branch of the) Roman Empire reflected a general decline in missions in the West. However, in the 6th century some stirrings are seen in the West. Patrick, Columba, and Columban in the British Isles in the late 6th century started this mission work. The Roman church did not have much to do with that. However, around the end of the 6th century, we find Pope Gregory the Great sending a missions group to England. This group was going to a place where Christianity has existed at least on some level for decades if not centuries. However, any positive move forward should be recognized. All of this work in the British Isles eventually reversed with the Celtic Missions movement of the following two centuries.

But things were different in the East. I chose 635AD for this post, because according to the Nestorian Stele, this was the year that the Christian Gospel arrived in China. We call it the Nestorian movement because they were from a church movement loosely tied to the theologian Nestorius. While it is common (especially in the West) to see Nestorianism (diophysitism) as heresy, the differences between it and orthodox beliefs are pretty subtle. To me, it is a doctrinal dispute long deserving of making peace over.

The push East seems consistently stronger than to the West in the First Millennium. The Alexandrian Christian teacher and philosopher Pantaenus apparently visited India at the end of the 2nd century and already found an active Christian church there. While there is a question on how that church started, its ties to St. Thomas (or perhaps St. Bartholomew) cannot be completely discounted.

The Western Church was tied to the Roman Empire (Western half in Rome) and the Eastern (Orthodox) Church was tied to the Eastern half of the Roman Empire (in Constantinople). This tie to the state gave it (or them, depending on how you see the church) strength and protection. However, neither were particularly motivated to take international missions particularly seriously. The Nestorians had its roots more tied to the Antioch church and was gradually pushed east through political action. This relative statelessness seems to have helped it spread.

Of course, what help could later hurt. China, welcomed the Nestorian teachers but when there was a change of dynasty, their work was crushed. When Muslim invaders came into Central Asia, their work was slowly stifled. Perhaps even more importantly, the squabbles between the imperial Christian faiths and the Nestorians (often seemingly driven more by power than belief) left them exposed. While the Celtic Missions could be absorbed by the Roman Church, the Nestorians were often labeled as heretics that needed to be destroyed.

And yet they weren’t destroyed. Nestorian Christianity still exists today. The exact numbers are hard to say. I see numbers like 200,000 or 400,000. Part of the problem is that many of them live in some of the more religiously repressive places in the world. Their early missionary zeal has shifted to a more insular “ethnic faith” for self-preservation.

Their ability to spread without state support, and endure hostility from other religions (including rival Christian denominations) and governments for centuries certainly point (to me at least) to a vitality of faith that should be recognized and honored.

Back at seminary, I wrote a paper on the Nestorian missions. You are welcome to read it by CLICKING HERE.

January 8, 2025

369AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Inspiring But Different

369AD was the approximate date of the completion of the translation of the Bible into the language of the Goths— a Germanic Language. This was completed before the Vulgate Latin translation (although Latin translation did occur before this). The Gothic Bible exists before the Armenian translation. That is kind of amazing considering that Armenia was the first “Christian nation.” Other early translations are Coptic and Syriac.

I am far from an expert in the background of the early language translations of the Bible. However, it does seem as if there is a difference between the Gothic Bible and the other Bibles. It seems to me as if the Gothic Bible was more of a missionary venture than the others. The translation was not just a translation into a new language, it was a translation into a new language group. Additionally, the translation was done fairly early in the evangelization of the Goths. Further, the language, much like Armenian, required the creation of an alphabet for written translation to occur. Again, I am open to correction on this, but I see the Gothic Bible as being the first missions translation.

Ulfilas (311AD to 383AD) lived through a time of transition in the Roman Empire. He was born in the year of the Battle of Milvian Bridge when Christianity became fully permitted, and even favored in the Empire, and lived two years beyond the date when it became the state religion.

Ulfilas was believed to be “bi-racial” at least in the sense of having one parent who was Cappodocian Greek and one being Goth. He is seen as the “Apostles to the Goths” although he spent only a few years north of the Danube. Still, his ministry to Goths within the Empire probably also included outreach beyond the borders.

The Gothic Bible is traditionally ascribed to Ulfilas as his own personal project. Many today think it was the work of a group of scholars. That is likely to be true, but it is also quite likely that he had a prominent, perhaps even leading, role in the activity.

Ulfilas is challenging for many missiologists today. Ulfilas was an Arian. That is, he believed that Jesus was a created being. As such, Jesus lacks co-eternality with the Father, and is less than deity. It seems like three responses I have seen have been (1) ignore this uncomfortable fact, (2) declare him non-Christian and so not relevant to Christian missions, and (3) look at him as being “only a little bit Arian.” It seems like (1) and (3) are the most common.

It did get me thinking. If Ulfilas was Arian, I am not sure how relevant it is to be just “a little bit Arian.” Would we listen to a missionary of Islam if he was just “a little bit Muslim”? That just seems weird.

It does seem to be part of a broader tendency to minimize the differences of people we want to find inspiring. Dietrich Bonnhoeffer was definitely not an America-style Evangelical Christian (theologically… politically), but one may not know this if one reads Metaxas’ book, or watched the Angel Studio’s biographical film. It is like we need to pretend differences don’t exist for us to find someone inspirational.

I kind of get it. I was raised up in the Christian Fundamentalist tradition. People were not generally seen as inspiring if they failed any sort of litmus test in terms of theology. The result ends up being either demonizing them and saying they have nothing to tell us… or pretend that the differences don’t exist.

I was reading “Soul Survivor” by Philip Yancey. One of the people he found inspiring was Mahatma Gandhi. This is despite the fact that Gandhi would not describe himself as a Christian. When Yancey wrote a positive article on Gandhi and Gandhi’s picture was put on the cover of an edition of Christianity Today, there were strong reactions. One reader question how it was possible to put the picture of a person on the cover who is presently “burning in hell.” The obvious question to this rather strong remark might be to ask the person “When did God give you the unique gift to read people’s hearts in light of God’s justice and mercy?” But perhaps even more valid would be the question, “Is it okay to be inspired by people who are not Christians?” Jesus appeared to be impressed by the faith of people who would not describe themselves as Jewish and perhaps not even a follower of Yahweh.

I also remember when I was very young and many people in my faith tradition considered Martin Luther King Jr. to be unworthy of listening to because he was an adulterer (sadly all too true), and a communist (a doubtful charge— classic bugaboo of cultural Christians in the US). But MLK had a message that American Christians really needed to hear. Discounting everything he said because of a (truthfully pretty inexcusable) failing is just wrong.

All of this meandering has a point. The three options I had above I think are flawed. Option #1… just ignore the differences doesn’t really honor the differences. Option #3 is perhaps even worse. One is minimizing the differences meaning that one is trying to place the other person in your own camp through deception. Option #2 is perhaps the worst. If we discount the wisdom of every person we can find fault with, we are likely to make ourselves fools, as well as those around us.

I think we can go for Option #4. We can find inspiration in people who we lack commonality with. We can find inspiration in another person while accepting, even honoring, the differences. Ulfilas almost certainly differed from me in a WIDE range of beliefs and practices. Those differences may in some ways be VERY important. At the same time, he can be a great inspiration as one of the first great cross-cultural missionaries.

January 7, 2025

Reflections on “Intentionally Blank”

Long long ago, I was in the US Navy. I attended Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island. For our PT (physical training— exercise activities) we would wear a tee shirt that was based on what company we were in. I was in “Alfa Company” and had a logo on the front that had the faux-Latin phrase “Illegitimi non Carborundum” (Don’t let the bastards wear you down). On the back we could choose our own personal message. I don’t remember what I chose… but I do recall NOT being embarrassed by it as the weeks continued. That is certainly a win. I still do remember a couple of ones that others had.

One in particular was a shirt that said in large letters on the back “Intentionally Blank.”

I liked it. I like things that are contradictory. I like seeing the word “YELLOW” printed with red ink. I like graffiti that tells us to “Obey the Law.” However, when I told the one with that shirt that I liked it, I was told there was more to the choice of message.

Military manuals often have pages that are empty of information except for the words “Intentionally Blank” written centered on the page. This had an important purpose. If one sees in a manual a completely blank page, one might reasonably wonder if there was a printing error. Perhaps valuable, even vital, information is missing. Putting the words “Intentionally Blank” is there to give comfort to the reader that the manual is complete— no data is missing. The manual creator wanted to have a blank page there, but did not want to worry the reader that something was lost. That does not imply that the manual is exhaustive, or contains everything possible on the topic. It just helps ensure the reader that the manual contains all that the writers wanted to inform the readers of.

Sometimes I wish that the writers of the Bible did this.

What day is Jesus returning? “Intentionally Blank”

What is the eternal fate of unborn or newborn children? “Intentionally Blank”

How can one find the clear boundary in God’s plans for us between God’s making straight our paths, and us choosing our way with wisdom? “Intentionally Blank”

How does God’s will and our individual wills interact when it comes to who are saved and how they are saved? “Intentionally blank”

What story was going on before the story that starts in Genesis 1:1? “Intentionally blank”

What amazing things is God doing on different planets around the Universe? “Intentionally blank”

How diverse can God’s children be in terms of faith and practice and still be recognized by God as His children? “Intentionally blank”

Personally I think it is important to reflect on the “Intentionality of God” in terms of revelation. God intentionally reveals to us what He believes we NEED TO KNOW, and intentionally holds back many things that we THINK WE NEED TO KNOW.

Perhaps that leads to related area of reflection. If there is a theological question that we really really want to know the answer to, but it does not appear to be revealed. Instead of trying to squeeze the answer out of God’s special and general revelation, perhaps we should reflect on what we want to know and why God might want us to not to know.

Or… perhaps it is not so much about God not wanting us to know, but instead is interested in us thinking, reflecting and speculating on something rather than having the process cut short by giving us the answers.

January 6, 2025

301AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Century that Changed So Much

In 301 AD, Christianity first became a state religion. (I know that legend has it that Osrhoene established Christianity as its state religion in the 2nd century… but even if true, that was only for a short time.) In 301AD, Armenia became a “Christian nation.” Eleven years later, with the Battle of Milvian Bridge, Christianity mainstreamed in the Roman Empire, and gained status as the favored religion, except during the reign of Julian the Philosopher (or Apostate if you prefer), until it became the state religion of the Empire in 381AD.

Being the state religion could be considered the “ideal” for participants in a particular faith. Being part of the state religion means one moves from being persecuted (to perhaps become the persecutor). Being part of the state religion means that the power that was in the hands of other people starts to flow to the leadership of one’s own faith. Being part of the state religion means that one’s religion often starts to become more attractive to outsiders (because of the change regarding persecution and power).

However, while many faiths are pretty comfortable with with this status. Christianity struggles at this because, from its foundation, the Christian faith was a religion of powerlessness. It idealizes servanthood and humility. However, the bishops of churches in the Roman Empire seemed to be quite comfortable embracing the new status. Eusebius of Antioch clearly expressed appreciation for Emperor Constantine and his self-described role of “bishop of bishops.” People can (and do) argue about whether this transition to Imperial Church was a good thing or bad thing. As a Baptist I am pretty firmly on the side of it being a bad thing (even though there are some Baptists today that appear enthralled at the possibility of state power). That being said, I am trying to focus on church history in terms of missions, not denominationalism. So how did this transition affect missions?

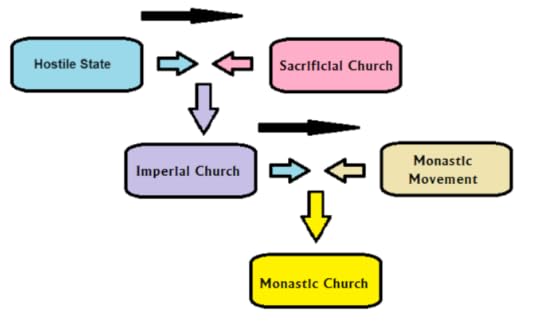

As noted in the figure above, there was a dialectic process going on. A hostile empire helped create a church that was persecuted, sacrificial, and populated by the deeply committed to their faith. The church was generally small but mighty. Overtime, the small and mighty church clashed with the hostile empire leading to an empire that was pro-Christian— leading to an Imperial church. This led to a popularization of Christianity that ended up “watering it down.” Living in the United States and in the Philippines, I still see a lot of social Christians— joining the church because of social connections rather than a faith that endures persecution. This has led in the United States, Philippines, and the 4th century Roman Empire, churches whose make-up (in terms of virtues and morality) is little discernible from the broader society.

In the Roman Empire, this “corruption” of the now popular church led to people being dissatisfied. Many of these separated themselves away, living a monastic life. Over time this style of living became corporate as these people joined together in faithful living and common purpose. This monastic movement was, in essence, a sodality structure, separate from the modality structure of the church. Later on, the monastic movement became less an exodus from the church, and more like a tool to revitalize the church and carry out specific works of the church (becoming in some sense, a monastic church).

From a missional standpoint, this century had mixed effects:

Positively, the transition to state church helped the church grow in size— rapidly.Negatively, the transition led to a church that had much less of a moral witness to the community… undermining its missional impact.Negatively, being a the religion of a state means that for surrounding nations and territories, Christianity becomes the “faith of the enemy.” This, potentially, undermines its international or cross-cultural impact. Positively, the monastic movement that developed in response to the changes going on in the church, eventually led to structures that were focused on missions. Missionary monastic orders became one of the greatest structures for mission work in church history.One final thing— the transition of a religion to a state religion leads to some greater level of identification between the religion and the people. From 301AD until now, Armenia identifies with Christianity even when ruled by Muslims and by Atheists. Much of the lands of the former Roman Empire identify deeply with their Christian heritage. Is this a good thing? Perhaps… or perhaps not. Is cultural Christianity a good thing? I truly don’t know. It feels like a good thing in comparison to when living under a hostile regime or faith. The church, however, has often been at its best in such hostile conditions.

So was the fourth century good for the missional church? Probably overall the answer is “Yes.” The growth of the monastic orders in the Eastern and Western churches have positively impacted missions even down to the present. But an argument could easily be made that the worst thing to happen to the church. Popularity, is not always a good thing.