Robert Munson's Blog, page 42

February 28, 2022

Paradoxical Ad Strategy

I am sure there is a nice term for this, but since I am not involved in marketing, I don’t know what it is. But here are a few examples.

A Christian theologian who I really appreciate moved his personal blog onto Patheos. Of course, Patheos has a LOT of advertisements on the webpage they provide. This theologian’s Patheos page is full of really cringy ads such as one related to divination (through one’s “personal angel”) or attempts to lure readers to some pretty sketchy groups that are definitely outside of historical Christianity.I was watching a very popular video on problems with NFTs and cryptocurrency. Youtube had advertisements on that video for various cryptocurrency vehicles.I was viewing a Q&A on a financial management website. There were a number of advertisements attached to it that recommended things that that website oppose.Not long ago, the musical “The Book of Mormon” was quite popular, and the LDS (largest Mormon group) advertised their religion targeting those who went to this show that was humorously adversarial and mocking of that faith.MLMs advertising on programs that oppose MLMs and more are out there. Why is that? At first it seems rather ridiculous. After all, if I am watching a show that does a good job of dismantling the logic behind NFTs, wouldn’t I be especially turned off by any group that is promoting that product? Probably, YES. However, that is not the point.

Suppose I want to sell people a Perpetual Motion (PM) device. (Such a device doesn’t exist, by the way.) Where would I try to market it. If I just set up a website for it, very few people would end up there, unless, I have some way of drawing them in. But suppose there is a science show (Youtube or some other media service) that has an episode that shows clearly why PM devices are impossible. One might think this is a bad place to advertise. After all, they are shown how foolish and impossible your product is. But there is a different way of looking at it. Many of the people who view this show are convinced by the show of the infeasibilty of PM devices. Actually, more likely they were already convinced that PM devices are impossible because they violate the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics. However, there are still likely to be many people who are more casually interested in the topic. These people one might call “Seekers,” or those who are interested in the topic of PM devices but may not have firm convictions. Some may even be believers in PM devices. It is likely that that there is a higher percentage of Believers and Seekers who view the show than there are in the general populace. As such, the advertisement is probably effective.

The same could be said with the other examples above. It seems a bit silly at first to advertise in a place that is actively hostile to what you are advertising… but upon further consideration, the people who show up there are probably more likely to be intrigued by your advertisement than the average person.

So what does that mean in terms of Christian ministry. Christians have often sought to use their group influence to shut down perspectives that are offensive to Christians (in societies where they have a dominant role). Maybe, however, instead of opposing them… support them. Support them by advertising with them. It is likely that a higher percentage of Seekers exist in a place that is attacking Christianity than where religion is not addressed.

I gave this example before. Several years ago, I took my son to an MMA fight in Baguio City. The fight is a blood sport (technically) and as such is rather questionable (at least to many). At the activity, there was a heavy metal band playing, among other things, AC/DC’s “Hell’s Bells,” ring girls in revealing outfits (revealing by Philippine standards anyway), Colt 45 beer being heavily promoted and given away, and generally a setting that many Christians would not be comfortable with. In that setting, right after the music and the beer give-away, the regular part of the event with an Invocation. A pastor came forward and did a prayer blessing the fight and all those who participated in it. I have often wondered if this was a good thing or a bad thing. I have kind of come to the conclusion that if I was asked to do the invocation I would decline the offer (gently). However, I am glad that a pastor DID accept the offer and remind people that God is with them and seeks to protect and bless. It seems kind of contrary to logic… but where people are struggling to be thrilled with the common cultural alternatives (sex, violence, booze, music, and spectacle), it may be exactly the right place to get them to think about God… even if for a moment.

But what about us? Is there a danger in the silly advertisements that show up tied to legitimate and instructional media? Yes. Illegitimate groups seek legitimacy in the minds of viewers through advertisements. Doing this (like using similar terminology and seeming to claim the same authorities) give a false association. This is especially true when the advertisement pretends to agree with the media it is attached to.

February 24, 2022

Post-Constantinian Christianity

It has become popular to say that certain countries, regions, or cultures are today to be labeled “Post-Christian.” The idea behind this is that in the past, the cultural norms, presumptive beliefs, and government allegiances were tied to Cultural Christianity. I believe I must add the key term “cultural to Christianity since a lot of the hallmarks used to identify Christian have little to do with Fruit of the Spirit, or obeying the Great Commandment. Cultural Christianity is often often tied to issues of government, law, and economics. Frankly, it is hard to say with much confidence what governmental form is Christian. Moses and Joshua led a chiefdom. The Judges like Deborah and Jephthah led a tribal confederacy. David and Hezekiah led a classic monarchy. Zerubbabel and Nehemiah served as provincial governors of a (pagan) empire. The New Testament, frankly, works under the premise that Christians will live under a governmental system that is either hostile or ambivalent to them. Economically, one can read parts of the Bible and believe that God is a Laissez-faire Capitalist, and other places a Laissez-faire Socialist. Much of cultural Christianity deals with things that God is not all that interested, and in some cases actively opposes (noting, to be cautious, that I could be wrong).

It is probably best to say that the Bible supports a Christianity that is counter-cultural with no presumption of control over government or the economy. And that was true before the Emperor Constantine (ignoring Armenia, Adiabene, and Osrhoene). While Constantine did not make Christianity the “law of the land” (others did that later), he did give Christianity status and influence within the Roman Empire. Power was given to Christian leaders that went beyond their own congregations. And by taking on the self-assigned role of Bishop to bishops, Constantine made Christianity as part of the system. So while the Kingdom of God was in opposition to the kingdoms of this world, but the Church was not.

Prior to Constantine (Pre-Constantinian) the church grew despite (or perhaps because of) modest to severe persecution. With Constantine the church grew fast, but the church changed drastically and not necessarily for the best. The symbols of power were taken on by the bishops, and money flowed in from the government. In many ways the empire entered the church far more than the church entered the empire.

From Constantine onward, there were a lot of attempts to link church and state. The United States was one of the first big-scale attempts to separate the two in Western Christianity, followed by the more extreme (first) French Revolution. It was, however, not until the 19th and 20th centuries where Christendom was truly seen as problematic. The Church needs to be protected FROM the government more than it needs to be protected BY the government. Arguably the broader society needs the example of Christians rather than the coercion from Christians.

There is a cost for this link of Church and State. Only a few years ago, January 1, 2000, the government of Sweden formally broke official ties with the Church of Sweden. While the response wasn’t unanimous, it seems like the Church of Sweden rather liked the divorce. The special status the church had also resulted in the government having a fair bit of control over the church leadership and policies. Some members of the leadership of the Church of Sweden appeared to welcome the removal of that control. I am not a Swede by nationality (although my ancestors did come from Sweden) so I don’t know whether the separation was a good thing or not. However, I come from a Free Church tradition that generally sees separation of Church and State as a good thing (although some of my Free Church friends in the US seem to be rethinking that issue a bit lately).

It seems to me that Jesus was always counter-cultural. Some people believe that counter-cultural means anti-cultural. That is far from it. Counter-cultural means to be fully enculturated into a society and stand out in only specific purposeful ways. Jesus was so linked to 1st century Palestine (Judea and Galilee) that He needed to be identified by one of His friends for His arrest. He ate, drank, talked, and socialized like the people of His time. Yet, in certain key ways, His life was a testimony against certain beliefs (even worldview beliefs) in the society in which He resided.

We live in a Post-Constantinian era for the church. We (as in ‘the Church’) no longer have unquestioned sway (in most parts of the world) over government or the broader non-Christian populace.

While I think it is naive to think that one can recapture the past, some different things in the past are better than others. Recapturing Constantinian Christianity is not one we should desire to recapture. Recapturing a Pre-Constantinian (now more appropriately called Post-Constantinian) Christianity I think is a good thing. It should be embraced… welcomed.

Far too often when the church tries to use political power to attempt to solve societal problems, we become part of the problem.

February 22, 2022

Church and Missions Relationship

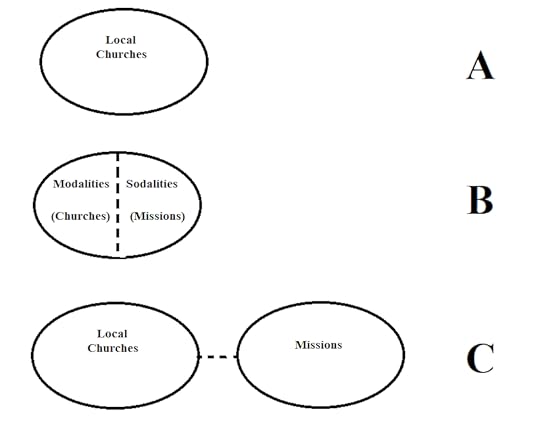

How one sees the relationship between the church and missions has ramifications on how one sees missions. Consider three perspectives as shown above.

First let’s consider OPTION A. With this perspective, the church consists of local churches only. Missions occurs only to the extent that local churches directly carry out missions. There are two groups who embrace this perspective as far as I can see.

Churches that embrace a “Primitivist” perspective can see things this way. In this view, The local church is the only institution that is God-ordained to carry out His mission on this earth. Such groups are normally very limited in mission work. For some such groups this is exacerbated by a hyper-Calvinist theology that sees God’s predestination as negating the need for mission outreach by the church. But even for those who don’t embrace this, the rejection of specialized structures outside of the local church does hurt their competency for outreach.Churches that embrace the Missional Church movement can move TOWARDS this perspective at least. The local church is missional at its core and so focus is placed on the church organizing and doing missions more than partnering with outside mission organizations. This can be quite commendable. My wife and I were sent out by a local church not a mission organization. However, the lack of specialized structures to deal with the unique challenges of cross-cultural work can be a challenge. In the case of my wife and I, we established ministries not directly tied to a local church, and also work with and through a seminary (which is a sodality structure, much like mission organizations).Let’s jump ahead to OPTION C. In this case, mission organizations are outside of the church in some way. There is a strong separation. Those who embrace OPTION A sometimes start here. They see the universal church as from God and missions (mission organizations) as not part of the church. Thus they reject mission organizations (and other sodality structures) entirely. However, others can do a similar thing. One might argue that the Roman Catholic Church, Orthodox Churches, and Anglican Church works this way with two separated groups— Diocesan or Secular priests and Religious Priests. The first group is tied to a bishop and normally linked to a parish/church. The second group is tied to a religious order— many of which serve as the missionary arm of the denomination.

In the latter case, it could be argued that there is a strong connection between religious orders and parishes in the Catholic Church (for example). In fact, in 1978 there was a push state that religious orders existed within the local church— autonomous but not independent. Be that as it may, history has at times (including in Protestant circles) where a denomination has a missionary arm that is funded and overseen by the denominational leadership, but whose link to and influence on the local church is very indirect. As the link becomes more tenuous, the missional vitality of the local church wanes.

In between is OPTION B. To understand this, I like to draw on different views of God. One view of God is Unitarian (Unitarian Christian groups, along with Muslim and Jewish groups). In this view. God exists as unity and there is no discernible structure within God’s unity. This is rather like Option A. Another view is Tritheism. This is where God is not a unity but exists as multiple beings (gods rather than God). These gods may have some form of relationship between them, but far from existing in terms of unity. The Hindu “Trinity” or the “Trinity” of Mormonism. This is rather like Option C. In between is historic Trinitarianism (or Binitarianism as well, I suppose). With this view, God is seen as Unity (not gods) but there is discernible structure within that unity. This is somewhat like Option B. The universal church exists as the assembly of the faithful, but there are discernible structures within that unity. Some are people-structured (local churches and bible studies, for example), while some are task-structured (mission organizations, training organizations, helps ministries, etc.).

To me, Option B has the best POTENTIAL. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t have problems. But seeing the work of God done by the church as existing not only in terms of work down by modalities, but sodalities, best fits the calling of God in the Gospels and Acts, as far as I can see.

Still, these three Options are still VERY GENERAL. Each has a wide range of minor variations that need to be considered.

Ultimately, we need to find a way to honor and empower the specialization needed often to carry out specialized work, without pushing such specialization completely outside of the church.

February 16, 2022

Quote on “Weak” Missions

“Any mission that does not measure up to the Kingdom of God is not a true mission. Mission is solely for the Kingdom of God. Mission comes from the Kingdom of God, and is executed for his reign.

Therefore, as Jesus did his mission from a position of weakness on the cross for the Kingdom of God, we should do our mission in like manner as Jesus Christ, whose mission characterizes a position of weakness. Only by following in the footsteps of our Master, can we be faithful to the mission for the Kingdom of God. …

Our ministry is not to be judged by the outward success of a ministry, but by the issue of whether we have been faithful in our mission or not, as in following in the footsteps of the Lord Jesus Christ. Some people may be afraid that when we begin our mission from a position of weakness we may have poor results due to ineffectiveness. In reality, the opposite can be true. The most effective mission or the mission that can bear maximum fruits turns out to be mission from a position of weakness. In our mission, nonetheless, the outward result or effectiveness of the mission should not be a priority, because in human eyes success can be very deceptive. True results or effectiveness will appear in the long run. Often times, it is fully understood when the next generation observes history. …

Throughout history, many missions that were so fruitful and sacrificial and thus fruitful in God’s eyes, were not recognized as fruitful by the contemporary observer, including even Christian leaders. Those missions were often regarded as failures.

Paul Yonggap Jeong. Mission from a Position of Weakness. Page 4

….

February 15, 2022

Is Kabunian Jesus? Part 2

I really think you will need to read Part 1 to make any sense of this post. You can CLICK HERE.

I suppose I might summarize the first post in saying that one should reject naivety in presuming that a simple YES or NO suffices. Kabunian (a central mythological figure in Cordilleran traditional religion) is NOT Jesus (the central historical figure of the Christian faith). However, there are enough similarities to wonder whether one can use Kabunian as a bridge to the Christian faith, especially since it is quite possible that Kabunian changed through interaction with Christianity such that the deity has taken on a some characteristics we would associate with Christ. I have written before on the Longhouse Religion of the Iroquois as a faith that bridges the polytheistic older faith of the people with the Christian faith. For some people the Longhouse Religion has kept people from converting to Christianity. For others, I believe it has served as a bridge to Christ.

I have talked to a number of Christians over the years who are Cordilleran. Generally the view is that one cannot use Kabunian in any way in the Christian faith. Kabunian is seen as too interwoven into the traditional religion so that it is seen as mixing bad with good, or syncretistic. One cannot separate the name from its associated worldview and beliefs. Myths have power. Sometimes such power is beneficial. Paul used the myth of Epimenides and the Unknown God and its powerful place in Athenian thought to express key aspects of the Christian faith. I doubt however that Paul kept using that myth during the discipleship phase of those who converted to following Christ. I could be wrong of course. On the other side, the powerful role of Olympian gods in Hellenistic regions could also undermine Christian ministry. In Lystra, Barnabas and Paul did miracles— presumably not only as acts of compassion, but also as signs of the veracity of their message. However, the firm belief of the locals in the Greek myths led them to interpret these acts as evidence that Barnabas and Paul were Greek gods walking among them. Myths have power to enlighten as well as to confuse.

Perhaps there is a better question that can be asked:

CAN KABUNIAN POINT TO CHRIST?

In this view, we start asking the question of whether God is at work in other faiths and cultures, utilizing the hopes and fears to slowly draw them to Himself. If one takes this view, Kabunian is NOT NECESSARILY a snare of Satan. He could be a human construct that informs us of what people in the culture value most. Or it could be a divine work that can serve as a redemptive analogy, a preparation for the gospel.

Or maybe it is all three. Regardless, it is not a healthy endpoint. In the most positive expression, Jesus Christ FULFILLS Kabunian. Kabunian points in some sense to Christ. The qualities of Kabunian that meet the genuine spiritual need of the people point to Christ, who can ultimately meet those needs. And those aspects of Kabunian that fail to meet those needs point ultimately to Christ because of that lack.

As I said in my last post, I am in no way and expert of Cordilleran Traditional Religion. As such, when I talk to my students and friends who take a very negative stance regarding this faith and theology, I am simply not in a position to tell them they are wrong. In fact, I really am compelled to trust them in this. I have read a paper that takes the ethical system of the culture (‘Lawa at Inayan’) in a very positive light. But it appears to be an exception to the rule— at least among Evangelicals.

However, I would add a small caveat. This caveat is that when one meets a Cordilleran who embraces the traditional religion… or (often more commonly) expresses their faith with a syncretistic mix of that religion and Christianity… don’t react with repulsion. See how their genuine hopes and fears are expressed through their faith, and how their faith can serve as a bridge to the One who can, ultimately, satisfy these hopes and relieve these fears.

I do believe that Christ may not be expressible in terms of Kabunian, but that Christ ultimately can be expressed in ways that honor the best of Cordilleran culture (rather undermining and replacing). Jesus challenged much of Jewish culture while ultimately be a fully inculturated Jew.

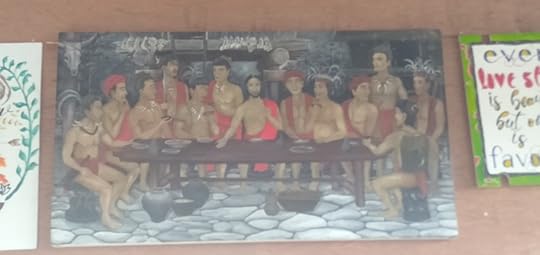

What would Jesus look like as a fully inculturated Cordilleran? I saw a picture of Jesus, with His disciples, as a Cordilleran. The image, of course, is far from adequate to answer that question. Still, I think the image points towards a better expression of Christ than we often see where I live. At least it opens the door to questions that need to talked about in community. I will share that picture here again. (The picture is in a Cordilleran restaurant, Ay Wada Casa Lomi House, outside of Baguio City, Philippines. Sorry for the poor quality of my photography skills.)

February 14, 2022

Is Kabunian Jesus? Part 1

We had an interesting, even if short, discussion in class on whether it is okay to say/believe that Jesus is Kabunian. For those not from a very specific part of the world, this question is meaningless or at least confusing. However, similar questions have come up in many settings. For example, “Must one use the term ‘Jehovah’ or ‘Yahweh’ as the God of the Bible?” as some Jehovah’s Witnesses and some Messianic groups suggest? Is it okay to say that the God of the Bible is Allah, or that the God of the Bible can be called Allah?” Perhaps it is easier to discuss this with less emotional baggage (for many Christians at least) with the case study of Kabunian.

Kabunian is the traditional deity (or prime deity) of the peoples of the Cordillera mountains of northern Luzon Island (Philippines). While a majority of Cordillerans would identify themselves as Christian, Kabunian still has a strong role in this region. Some argue that early Cordilleran religion was built around spirits and ancestors, and the focus on Kabunian is a fairly late evolution of the faith that post-dates contact with Christianity. As such, Kabunian did not have a strong role in the religion until he was needed as an alternative to the God of Christianity. Truthfully, I am not an expert on Kabunian or of Cordilleran traditional religion. Because of this, I truly don’t know if this is actually true, or is a false reinterpretation of that faith.

But this gives one POSSIBLE reason for saying that Kabunian can be said to be Jesus. PERHAPS KABUNIAN IS A LOCAL CONTEXTUALIZATION OF JESUS. After all, if Kabunian developed in response to Christianity, couldn’t it be seen as a local expression of Christ? I have issues with this idea. A contextualization is more than simply grabbing a term and linking it to another. The name Kabunian means, essentially, “The one to be prayed to” (in the Kankana-ey language). Kabunian as chief god and the one to be prayed to certainly aligns with Christ. However, the stories of Jesus and the stories of Kabunian don’t really line up. The teachings of Kabunian and Jesus don’t really line up (sometimes). That is also a major issue with linking the God of the Holy Bible and Allah from Al-Qur’an. Although there are historically common roots, and Arab and Aramaic Christians called the God of the Bible Allah before the time of the founding of Islam, many of the characteristics of each do not align. Because of this, lazy conflation can lead to confusion. Confusion can be a problem and lead to syncretism. However, to simply reject everything local and simply bring in an outside term can lead to its own form of syncretism— unhealthy mixing of the Christian faith with an outside, rather than local, culture. So let’s consider further.

On the other hand one could make the argument that Kabunian CANNOT be equated with Jesus because the two names are different. Relatedly, some would say that Kabunian is pagan and so can have no part of Christian theology or terminology. On this I think we have to be a bit cautious. While YHWH appears to be a Hebrew-only term, Elohim appears to have been connected with the Phoenican god El. Does that mean that the two are being equated? Well, Yes and No. Let’s take it further, in the New Testament, the dominant term used is Theos. This term has roots in the Greek culture and religion. The term Theos seems to have a link to the term Zeus, the chief Olympian god of the Greeks. Supposedly, the English term ‘God’ has a similar connection to Odin or Wotan, through the proto-Germanic term “Godan.” Does this mean that we have to throw away all terms for God in Christianity with pagan roots. I would argue that the answer is decidedly NO. If one takes the individual cases above, in the case of Elohim, the term may be linked to El, but is transformed in both its written form, but in its meaning as well. Elohim is above all creation and “gods” much as is the Phoenician god El, but differs as God is NOT the father of Baal and Ashtoreth (among other differences). The choice of term draws people to think of the God of Israel as the god of the heavens but its transformation helps avoid too close of a link. The same could be said in the New Testament. The Bible used the Greek term Theos for god, but did not use Zeus. One could argue that there is too much baggage associated with the character Zeus, but there is value in the more abstract Theos. Likewise, in English, the term Odin has too much pagan baggage, but the more generic/abstract term “God” is open for utilization. In places in Asia, for example, missionaries have often sought to equate the God of the Bible with the local expression of the god of the heavens. Is there problems with this? Sometimes there can be. There can be problematic baggage to deal with in the term. For this reason, sometimes the local term is not used, or it is used but changed somewhat. There is, however, considerable value in helping people understand that the God of the Bible is their God as well. In the Philippines it is more common to use the term “Diyos” which is a Spanish term that ultimately traces back to the Greek Theos. At other times, the term Panginoon is used, which is seen more as a descripter of God rather than a name for God.

I think perhaps a better goal in language is that of “Fulfillment” rather than EQUATE OR EQUIVOCATE. We can talk about this in Part II. To go there direction, you can CLICK HERE.

February 13, 2022

Book Review: “Encountering Theology of Mission” (Ott, Strauss, Tennent)

The book, Encountering Theology of Mission: Biblical Foundations, Historical Developments, and Contemporary Issues by Craig Ott, Stephen J. Strauss, with Timothy C. Tennent, is the best Missiology book I have read in quite some time. I just finished reading it about 2 hours ago, so I don’t think this will be a carefully crafted review… but I hope that is okay.

ENCOUNTERING THEOLOGY OF MISSIONS: BIBLICAL FOUNDATIONS, HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS, AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES. Craig Ott, Stephen J. Strauss, with Timothy C. Tennent (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010). Part of the Encountering Mission series.

ENCOUNTERING THEOLOGY OF MISSIONS: BIBLICAL FOUNDATIONS, HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS, AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES. Craig Ott, Stephen J. Strauss, with Timothy C. Tennent (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010). Part of the Encountering Mission series.When I first began reading the book I was a bit down on it in that it did not seem to have a theme or framework. But clearly, the goal of the book is not to give a single clear theological vision for mission (or missions), but to review the landscape and range of perspectives in the Theology of Mission. This certainly not only adds to its strength as a textbook, but also helps those involved in missions to come up with our own perspectives. As the sub-title suggests, it addresses Biblical Foundations for missions- but it is more than most such Biblical foundations which (at their worst) is little more than quoting a lot of Scripture verses. It deals with Historical Developments of missions and does do honor not only to Evangelical Protestant missions, but Catholic, Conciliar, and Orthodox missions as well. And it deals with many of the Contemporary issues that are bandied about today.

While the perspective of the writers is clearly Evangelical, the book does not try particularly hard to be a defense of Evangelical perspectives. It criticizes some perspectives within the Evangelical world with regards to missions, often shows respect (even if respective disagreement) with perspectives from others, and is cautious in generally avoiding strong dogmatic statements.

I will add two negative comments here.

First, there are some topics that I feel were glossed over a bit. The Honor/Shame Theology versus Guilt/Innocence (to say nothing about other models of connecting Christian theology to worldview categories) was not addressed more than off-hand. I understand that the book came out in 2010, but I do feel like these issues were around enough at that time to be seen as a real contemporary issue worth dealing with more. Additionally, the section of contextualization did not do much in the area of tests for good localized theology versus bad. In this particular case, the book did speak to this issue more than just off-hand. To me, however, it could have benefited from an in-depth review.

Second, I felt that it was a great book that was really let down by the final chapter. That chapter “The Necessity of Missions” did not really need to be there. It dealt with three “uncomfortable questions.” that are related to the justice and fairness of God. These are good questions, but are starting to move away from Theology of Mission into Soteriology and Theology Proper. It does feel like the authors simply weren’t that strong in those topics. The issue of Hell was especially weak in my mind. It did not deal with the wide range of perspectives regarding the nature of Hell…. limiting to three perspectives, and even then only covered one in-depth (the one they supported). It went into a fairly unconvincing Biblical justification for the ECT (eternal conscious torment) perspective. That seems pretty out of line with the rest of the book that tried to be multi-perspectival and sought to avoid verse-bombing. Personally, I am in the undecided category regarding much about the nature of Hell because the Bible is shockingly vague in this area. I can’t really complain that the authors have a perspective on it— that is fair and reasonable. I, however, feel like this chapter was added as a bit of an afterthought and was not well developed. I would say that I do find it curious that there seems to be a presumption in the last chapter generally that Christians should find it more motivational to do missions if non-believers experience eternal conscious torment then if they are consumed and perish. (Frankly, why would missionaries feel greater motivation to faithfully serve a God who appears to be less fair and merciful, humanly speaking, than one who appears to be more fair and merciful.) I am not trying to make a big point about Hell and about the Justice of God, but, again, I feel that the final chapter was added in a rushed manner based on editorial comments. I could be wrong.

I spent way too long on these two negative comments. If I ever get a chance to teach Theology of Mission again, I will definitely use it as a key textbook (unless something more updated comes along). I must commend the high quality of the book, and recommend it to all interested in this topic.

February 5, 2022

Escaping the Labyrinth: A Parable

The story of Theseus and the Minotaur is well-known. In the story, Theseus volunteered to enter the Labyrinth— a maze-like structure created by Daedalus, in the Minoan capital of Knossos. Doing so was considered a death sentence. Either Theseus would be killed by the Minotaur, a creature who is half-man and half-bull who roamed the Labyrinth, or he would become hopeless lost in its twisted, confusing passages. However, the daughter of King Minos gave Theseus a thread that he could unwind as he traveled deep into its depths to give him a return path.

One can, perhaps, add a tiny bit to the story. One can imagine that Theseus had just killed the Minotaur. As he began to wind the thread to guide his way out, he saw some shapes begin to come out of the shadows. He soon found that there were several others who lived in the Labyrinth. These were other enemies of King Minos who were sent into the Labyrinth as their punishment. They had managed to stay out of sight of the Minotaur, only coming out when he slept, to gather food scraps for their own survival. Their lives were a daily misery, but now one of their great concerns, the Minotaur, was dead. One more remained, getting out of the Labyrinth.

After greeting each other, Theseus said, “Please join me friends. I know the way out.”

One responded, “I don’t know. There is a breeze I have noticed that comes out of the passage near the Minotaur’s sleeping chamber. I am sure that must mean that it is a safe passage out of here.”

Another said, “That passage is heading downward. Escape must be upward not downward. Above us light comes in. Now that we are safe from the Minotaur, I can tie together wood scraps to make a ladder to climb to freedom.”

Yet another said, “That’s dangerous. We need help from others. Now that the Minotaur is dead, all we have to do is leave a note in the lift mechanism that the King’s servants use to lower food to the beast. Once, they know he is dead, certainly they can be convinced to pull us up out of this pit.”

Theseus was frustrated and spoke over the bickering group. “Friends!” he said. “What you all are saying makes sense I suppose. Following a moving air, or light above, or maybe friendly outsiders may work. I don’t know. Maybe there are a hundred ways out of this place. But the one thing I know is that I have the thread and it connects this place to the entrance of this place. I will follow it, and I will get out. If you want out, I recommend following me. Otherwise, all I can do is wish you well and pray your plans work out for you.”

With this, he began following the thread again. How many followed him. I don’t know. Of those who chose their own way, we don’t know how many found their way and how many were trapped there until their deaths.

All we know is that Theseus was saved by a thin thread that led to his freedom..