Michael Swanwick's Blog, page 6

June 5, 2025

J. R. R. Tolkien's Winooski

.

Look what I found while going through some old papers!

Here, before your eyes, is where my career as a fantasist began. With a drawing by a junior high school student who had just read the Lord of the Rings trilogy and would never be the same again.

I was in high school in Winooski, Vermont when... But I've already told this story, in an essay titled "A Changeling Returns, written for and published in Meditations on Middle-Earth. Here's the pertinent excerpt:

… in myhigh school days, my sister Patricia sent home from nursing school a box ofpaperbacks (I can see that box now, freshly opened and full of promise) whichshe had read and no longer wanted. Amongthem was The Fellowship of the Ring. Ipicked it up late one evening, after finishing my homework, meaning to read achapter or two before sleep. I stayed upall night. It wasn’t easy, but byskipping breakfast in the morning and reading every step of the way to school,I managed to finish the last page just as the bell rang for my first class tobegin.

Oh, how that book shook and rattled me! It rang me like a bell. Even today, when I am three times as old as Iwas then, I can still hold my breath and hear the faint reverberations fromthat long, eternal night. That readingmade me a writer, though it took me forever to then learn my craft. It showed me what literature could do andwhat it could be.

As an adult, I am painfully aware of the deficiencies of that drawing. But it's a good indication of how enthusiastic I was about Tolkien's great work. And, to be fair to the kid who drew it, I haven't gotten any better as a visual artist in the decades since then.

*

June 4, 2025

Singular Interviews: GREER GILMAN

Marianne Porter's latest Dragonstairs Press chapbook, Singular Interviews, will be offered for sale at noon Eastern time this coming Saturday, and sell out shortly thereafter. A quarter-century in the making, each of my interviews with a science fiction or fantasy notable is exactly one question long. This week, I'm posting three of the interviews on this blog. Here's the second of them:

SINGULARINTERVIEWS: GREER GILMAN

QUESTION: In Farah Mendlesohn’s and Edward James’ AShort History of Fantasy, they say that Cloud & Ash is writtenentirely in iambic pentameter. Can thispossibly be true?

GREER GILMAN: Well, not pentameter, as it’s not in lines,but yes: iambic Xameter, endlessly enjambed.

*

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman",serif; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

June 2, 2025

Singular Interviews: JOHN CROWLEY

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-font-kerning:1.0pt; mso-ligatures:standardcontextual;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

Marianne Porter's latest Dragonstairs Press chapbook, Singular Interviews, will be offered for sale at noon Eastern time this coming Saturday, and sell out shortly thereafter. A quarter-century in the making, each of my interviews with a science fiction or fantasy notable is exactly one question long. In the coming week, I'll be posting three of the interviews on this blog. Here's the first of them:

SINGULAR INTERVIEWS: JOHN CROWLEY

QUESTION: You have been working on Aegypt forrather a long time, and you're currently years from completion of this enormousfour-book project. Why are you engagedin such a large and time-consuming single work?

JOHN CROWLEY: God knows. God help me. For having everstarted this. When we are young we thinkthat life will go on forever. When wegrow older, we realize that life has shapes. It's time, it seems to me, to find out that the largest stretch of mycreative years is going to be taken up with a project that will probably be themajor thing that I do in life. That'sscary. That's a terrifying thought. You try to preserve possibilities. You try to have a life that continues to openout, even though you know it doesn't. And the idea that it doesn't, and that life has shapes, is borne in onme as I work on this book. It's not likeI will go on and write dozens of books. I don't know what they are. No, Iknow what they are, and I am already in the middle of writing one of them. I don't know why. I wish I knew.

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-font-kerning:1.0pt; mso-ligatures:standardcontextual;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

*

May 31, 2025

Coming From Dragonstairs Press: Singular Interviews

.

A quarter of a century ago, I was sitting in the bar at a Worldcon, chatting with John Crowley, and realized that it was an excellent opportunity to ask him a question I'd been wondering about. And, as it happened, I had a cassette tape recorder with me. So I got his permission, turned the recorder on, and asked.

Thus began a project that has just now culminated in Singular Interviews, the latest chapbook from Dragonstairs Press. Off and on, over the years, I would take the recorder with me to conventions and periodically ask people a single question. Later, I conducted more interviews via e-mail. Most of which were published one at a time in the New York Review of Science Fiction, though the last two or three are new to print.

Marianne Porter has collected these brief interviews in a beautifully crafted chapbook. The one-question interviewees are: John Crowley, Tom Purdom (a witty joke), Eileen Gunn, Gregory Frost, Paul Park, Mike Resnick, Samuel R. Delany, Karl Schoeder, David Hartwell, Henry Wessells, Greer Gilman, Spider Robinson, Fran Wilde, Tom Purdom (a serious answer this time), and Michael Moorcock.

What I like most about this project is how differently all the writers (and one editor) answered their question. But you don't have to take my word for it. I'll be posting three of the Singular Interviews this week, in the lead-up to the sale.

And for those interested in buying a copy . . .

The Dragonstairs Press notification letter has just been sent out. It contains all the ordering information and is reprinted below verbatim:

SingularInterviews is a collection of one question interviews conducted byMichael Swanwick, with a variety of science fiction and fantasy'sbest and brightest. The interviews were carried out over many years,and have previously been published in the New York Review of ScienceFiction. They are collected here for the first time.

The elevensubjects include Greer Gilman, John Crowley, Mike Resnick, DavidHartwell, and Samuel R. Delany, among others. The questions rangefrom insightful probes into professional intentions to bits of whimsyabout Jules Verne's appearance as Guest of Honor at Philcon.

Offeredin an edition of 60, Singular Interviews are hand stitched, bound inIndian 100% cotton paper in various colors, numbered and signed bySwanwick. They will be available at noon, Philadelphia time (easterndaylight savings) on June 7, 2025 at www.dragonstairs.com.

*

May 16, 2025

Chesley Bonestell's Lost Industrial Lithographs #32 of 32

.

Liquid Air Plant

This is possibly my favorite of all the lithographs. Fantastic use of perspective and evocation of lighting.

This concludes what has been an adventure for Marianne and me. We discovered the lithographs in an auction, were astonished by their size at the viewing, and won them when nobody else realized what they were. And then began a long search for an institution with flatbed scanners (putting paper that was over a century old through rollers is a recipe for disasters) that would be willing to do the scanning.

Long story short, we found one. And now these images belong to you and the world.

These images have been downsized to fit Blogger's requirements and limitations. On Monday, I'll post info on how you can download high-definition versions of all of them

Thank you, Chesley, for giving Marianne and me a wonderful experience.

And for those who came in late . . .

In 1918, Chesley Bonestell was commissioned to create a series of lithographs chronicling the construction of the government cyanamide nitrates plant in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It would be many years before he began painting the astronomicals that made him famous, but he already had tremendous technique.

The lithographs disappeared from public view not long thereafter.

Recently, my wife, Marianne Porter, and I bought what we think is a complete set of 32 at an auction. We had electronic files made of them, which we'll be posting here, one every weekday until they're all online. Then we'll make a torrent containing the complete collection in high density form, for whomever wants them.

All the images are in public domain. You don't have to ask anybody for permission to download them and you may employ them however you wish.

*

May 15, 2025

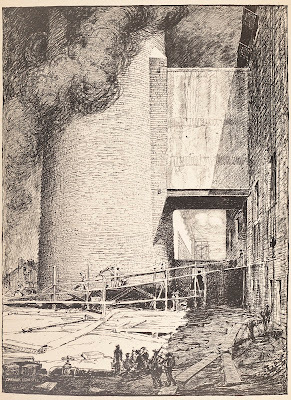

Chesley Bonestell's Lost Industrial Lithographs #31 of 32

.

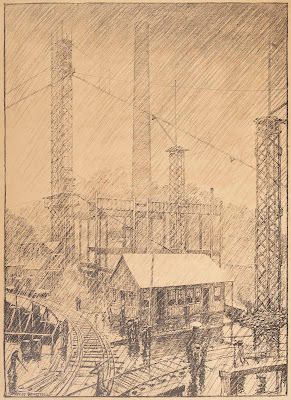

Chimney in the Rain

If you've been following this series, you'll recognize the chimney. It's in the background of a lot of the lithographs. It's the signature image of the nitrates plant.

And this lovely image is the penultimate lithograph. The last one will be published tomorrow. It's a stunner.

And for those who came in late . . .

In 1918, Chesley Bonestell was commissioned to create a series of lithographs chronicling the construction of the government cyanamide nitrates plant in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It would be many years before he began painting the astronomicals that made him famous, but he already had tremendous technique.

The lithographs disappeared from public view not long thereafter.

Recently, my wife, Marianne Porter, and I bought what we think is a complete set of 32 at an auction. We had electronic files made of them, which we'll be posting here, one every weekday until they're all online. Then we'll make a torrent containing the complete collection in high density form, for whomever wants them.

All the images are in public domain. You don't have to ask anybody for permission to download them and you may employ them however you wish.

*

May 14, 2025

Chesley Bonestell's Lost Industrial Lithographs #30 of 32

.

.Base of Boiler-House Stack

Another dark and Biblical image. It helps to remember that World War One was going on during the plant's construction, and that its purpose was to create munitions. It was a time of high seriousness for the United States.

And for those who came in late . . .

In 1918, Chesley Bonestell was commissioned to create a series of lithographs chronicling the construction of the government cyanamide nitrates plant in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It would be many years before he began painting the astronomicals that made him famous, but he already had tremendous technique.

The lithographs disappeared from public view not long thereafter.

Recently, my wife, Marianne Porter, and I bought what we think is a complete set of 32 at an auction. We had electronic files made of them, which we'll be posting here, one every weekday until they're all online. Then we'll make a torrent containing the complete collection in high density form, for whomever wants them.

All the images are in public domain. You don't have to ask anybody for permission to download them and you may employ them however you wish.

*

May 13, 2025

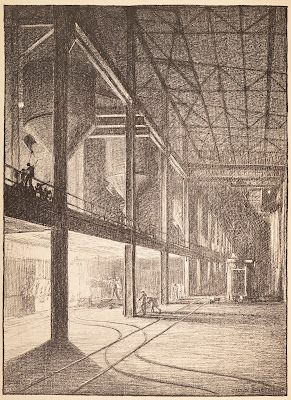

Chesley Bonestell's Lost Industrial Lithographs #29 of 32

.

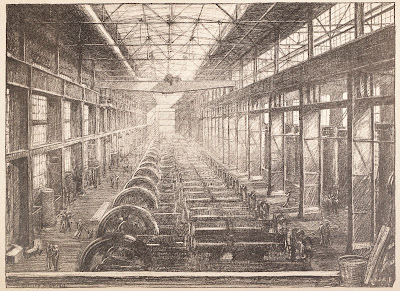

Carbide Furnace, Upper Level

Once again, Bonestell demonstrates his mastery of perspective. I love how the building recedes into shadow in the distance.

And for those who came in late . . .

In 1918, Chesley Bonestell was commissioned to create a series of lithographs chronicling the construction of the government cyanamide nitrates plant in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It would be many years before he began painting the astronomicals that made him famous, but he already had tremendous technique.

The lithographs disappeared from public view not long thereafter.

Recently, my wife, Marianne Porter, and I bought what we think is a complete set of 32 at an auction. We had electronic files made of them, which we'll be posting here, one every weekday until they're all online. Then we'll make a torrent containing the complete collection in high density form, for whomever wants them.

All the images are in public domain. You don't have to ask anybody for permission to download them and you may employ them however you wish.

*

May 12, 2025

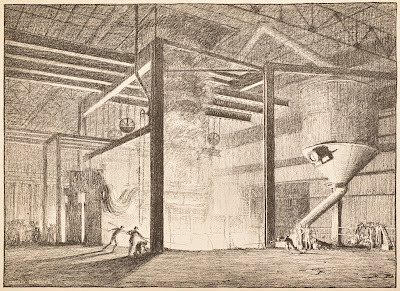

Chesley Bonestell's Lost Industrial Lithographs #28 of 32

.

Carbide Furnace Room, Lower Level

It's hard not to marvel at how we've lost touch with the epic scale of the structures that make the things a society needs. (In this case munitions, alas; but later, fertilizer.) Chesley Bonestell made these images back when such things were still celebrated.

This series will conclude on Friday.

And for those who came in late . . .

In 1918, Chesley Bonestell was commissioned to create a series of lithographs chronicling the construction of the government cyanamide nitrates plant in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. It would be many years before he began painting the astronomicals that made him famous, but he already had tremendous technique.

The lithographs disappeared from public view not long thereafter.

Recently, my wife, Marianne Porter, and I bought what we think is a complete set of 32 at an auction. We had electronic files made of them, which we'll be posting here, one every weekday until they're all online. Then we'll make a torrent containing the complete collection in high density form, for whomever wants them.

All the images are in public domain. You don't have to ask anybody for permission to download them and you may employ them however you wish.

*

May 11, 2025

Celebrating America! The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

.

250 years ago yesterday, the first American victory in the War for Independence took place when Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys took Fort Ticonderoga.

Factors favoring the Americans include that the fort was in disrepair and that it was manned only by a small British force of fifty soldiers. However, there was a honking big lake between Vermont and New York, where the fort was situated. Ethan Allen gathered together all the boats that could be found and launched a sneak late-night raid. But there were not enough boats for all the soldiers he had gathered together and dawn was coming. So, rather than lose the element of surprise, the raid commenced with eighty-three men and two commanders.

Complicating matters was Benedict Arnold, who had independently come up with the idea of a raid, gotten authorization from the governor of Massachusetts, and arrived in Vermont with a smaller force of men. He demanded to be put in charge but was hooted down by the Green Mountain Boys, who refused to follow anybody but their favorite native son. At last, an agreement was struck that he would march alongside Allen. Later, he claimed to be a co-commander, but documentation of this has never been found and, given Allen's personality, seems unlikely.

The attack was swift and sudden. A lone British sentry essayed one musket shot, which misfired, and fled. The Americans took over the fort and, when asked in whose authority he acted, Ethan Allen supposedly said, "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!" However, given that Allen was an atheist and that Vermont was at the time a functioning anarchy with no official ties to the Continental Congress, it is likely that he said something equally colorful by far less printable.

No soldiers on either side were killed or injured, save for one American who received a minor bayonet wound. The cannons and other munitions stored at the fort were later used to push the British out of Boston. And Benedict Arnold had suffered the first of many humiliations that would later lead him to turn traitor. When the Green Mountain Boys went home, he was left in command of the fort and a small number of troops--until Connecticut sent their own men up to claim the weaponry and make him subordinate to an officer who had seen no action. Arnold who had spent over a thousand pounds of his own money and received no glory at all, resigned his commission and went home.

Above: Image found at Warfare History Network, which has a far more detailed description of the battle here. It is disputed whether Lieutenant Feltham was actually forced to surrender with his trousers in his hand. But true or not it makes a great story.

*

Michael Swanwick's Blog

- Michael Swanwick's profile

- 552 followers