Michael Swanwick's Blog, page 152

April 14, 2014

Radiant Doors . . . the Series?

.

What this means is that if the network likes the script (now being written by Jeremy Doner), the series will be made. Justin Lin, the director of Fast and Furious 6 , will be the director and executive producer if and when Radiant Doors is made.

"Radiant Doors" is the single darkest story I've ever written -- and that's saying something. The premise is that one day radiant doors open in the air everywhere in the world and through them pour millions of refugees. They've all been terribly abused. And they're from our future.

I don't know anything about Justin Lin's vision for the series, and that's probably just as well. Neither he nor Doner needs me peering over their shoulders, second-guessing them. But in addition to the obvious benefits to me if the series is ever made, I'd love to see just what they do with the premise.

You can read all about it here.

Above: Justin Lin

*

What this means is that if the network likes the script (now being written by Jeremy Doner), the series will be made. Justin Lin, the director of Fast and Furious 6 , will be the director and executive producer if and when Radiant Doors is made.

"Radiant Doors" is the single darkest story I've ever written -- and that's saying something. The premise is that one day radiant doors open in the air everywhere in the world and through them pour millions of refugees. They've all been terribly abused. And they're from our future.

I don't know anything about Justin Lin's vision for the series, and that's probably just as well. Neither he nor Doner needs me peering over their shoulders, second-guessing them. But in addition to the obvious benefits to me if the series is ever made, I'd love to see just what they do with the premise.

You can read all about it here.

Above: Justin Lin

*

Published on April 14, 2014 05:56

April 11, 2014

Soundworms of the Galaxy

.

I'm in pod-print again! "Passage of Earth," which very recently appeared in Clarkesworld , is now available free for the listening as a podcast.

This story was the first I ever sold to Clarkesworld , and what struck me about the process was how fast it all was. From submission to acceptance was less than a week which, okay, is not entirely uncommon for me. But from Acceptance to epublication was a matter of weeks. And then, less than a week later (I would have blogged about this Wednesday, but felt obligated to do my small part toward notifying people about Heartbleed), the postcast is up as well.

Part of this, I'm sure, is that the electronic media are intrinsically faster than print media. But most of the credit has to go to publisher/editor Neil Clarke.

You can listen to the podcast here.

*

I'm in pod-print again! "Passage of Earth," which very recently appeared in Clarkesworld , is now available free for the listening as a podcast.

This story was the first I ever sold to Clarkesworld , and what struck me about the process was how fast it all was. From submission to acceptance was less than a week which, okay, is not entirely uncommon for me. But from Acceptance to epublication was a matter of weeks. And then, less than a week later (I would have blogged about this Wednesday, but felt obligated to do my small part toward notifying people about Heartbleed), the postcast is up as well.

Part of this, I'm sure, is that the electronic media are intrinsically faster than print media. But most of the credit has to go to publisher/editor Neil Clarke.

You can listen to the podcast here.

*

Published on April 11, 2014 07:08

April 9, 2014

Lock Up the Chickens! Change the Passwords!

.

I'm taking a break from my regular topics for the following public service announcement:

Change all your on-line passwords. Do it now. Then do the whole thing again a week from now, just to be safe.

I'm not kidding. A few weeks ago, a major security flaw -- dubbed Heartbleed -- was discovered which puts passwords, credit card numbers, pretty much any information stored on the Web at risk. This was kept a secret while the major players were given the opportunity to apply patches. A few hours ago, it went public. Which means that every cheap gunsel and two-bit grifter on the Web will be trolling for data.

Here's the problem in CNN's words:

The rest of the article can be found here.

For the xkcd cartoon explaining what's going on in a more lucid manner than most news reports, click here.

*

I'm taking a break from my regular topics for the following public service announcement:

Change all your on-line passwords. Do it now. Then do the whole thing again a week from now, just to be safe.

I'm not kidding. A few weeks ago, a major security flaw -- dubbed Heartbleed -- was discovered which puts passwords, credit card numbers, pretty much any information stored on the Web at risk. This was kept a secret while the major players were given the opportunity to apply patches. A few hours ago, it went public. Which means that every cheap gunsel and two-bit grifter on the Web will be trolling for data.

Here's the problem in CNN's words:

Heartbleed is a flaw in OpenSSL, an open-source encryption technology that is used by an estimated two-thirds of Web servers. It is behind many HTTPS sites that collect personal or financial information. These sites are typically indicated by a lock icon in the browser to let site visitors know the information they're sending online is hidden from prying eyes.

The rest of the article can be found here.

For the xkcd cartoon explaining what's going on in a more lucid manner than most news reports, click here.

*

Published on April 09, 2014 06:41

April 7, 2014

Tonight: A Few Laughs With Robert Sheckley

.

I'm Irish-American and my people believe that wakes should be fun. Hell, we believe that all memorials to the dead should be fun. In which spirit you are invited to the New York Review of Science Fiction's Tribute to Robert Sheckley tonight at 7:00.

The late, great science fiction writer, humorist, and satirist died a little over five years ago in bitterest midwinter. Tonight, his former wife Ziva Kwitney, his daughter (a noted author in her own right), Alisa Kwitney, legendary bookman Henry Wessells, and famed editor (who worked with Sheckley during the years when he was editor of Omni) Ellen Datlow gather to do the man honor. I'll be there too, and in such company I will most likely be uncharacteristically subdued.

If you're in Manhattan, why not drop in? The suggested donation is only seven dollars and if your finances are so tight you can't afford that much nobody's going to say peep.

Here's the info again:

New York Review of Science Fiction Readings:A tribute to Robert SheckleyWHO:

* Ellen Datlow

* Alisa Kwitney (Sheckley)

* Ziva Kwitney

* Michael Swanwick

* Henry Wessells

WHEN:

Monday, April 7th

Doors open 6:30 PM

HOW (much):

Free; $7 donation suggested

There will be cider, crackers & cheese.

WHERE:

Soho Gallery for Digital Art / Soho Arthouse

138 Sullivan Street

Above: Robert Sheckley's grave lies somewhere under the snow, in the Artists' Cemetery in Woodstock. I took that picture not long ago on my Geek Highways trek.

*

I'm Irish-American and my people believe that wakes should be fun. Hell, we believe that all memorials to the dead should be fun. In which spirit you are invited to the New York Review of Science Fiction's Tribute to Robert Sheckley tonight at 7:00.

The late, great science fiction writer, humorist, and satirist died a little over five years ago in bitterest midwinter. Tonight, his former wife Ziva Kwitney, his daughter (a noted author in her own right), Alisa Kwitney, legendary bookman Henry Wessells, and famed editor (who worked with Sheckley during the years when he was editor of Omni) Ellen Datlow gather to do the man honor. I'll be there too, and in such company I will most likely be uncharacteristically subdued.

If you're in Manhattan, why not drop in? The suggested donation is only seven dollars and if your finances are so tight you can't afford that much nobody's going to say peep.

Here's the info again:

New York Review of Science Fiction Readings:A tribute to Robert SheckleyWHO:

* Ellen Datlow

* Alisa Kwitney (Sheckley)

* Ziva Kwitney

* Michael Swanwick

* Henry Wessells

WHEN:

Monday, April 7th

Doors open 6:30 PM

HOW (much):

Free; $7 donation suggested

There will be cider, crackers & cheese.

WHERE:

Soho Gallery for Digital Art / Soho Arthouse

138 Sullivan Street

Above: Robert Sheckley's grave lies somewhere under the snow, in the Artists' Cemetery in Woodstock. I took that picture not long ago on my Geek Highways trek.

*

Published on April 07, 2014 11:20

April 4, 2014

Life Under Ice

.

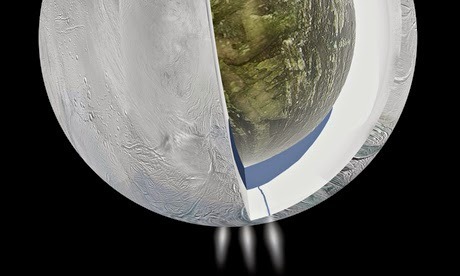

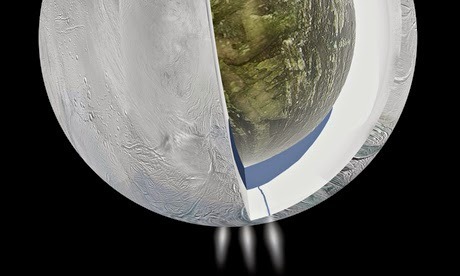

The recent declaration that Enceladus has a small ocean under its icy shell immediately put a relatively obscure moon of Saturn on the forefront of the search for extraterrestrial life. Simply because it's easy to imagine sending a probe to collect fresh water-ice from the surface and examining the sample for microscopic life or traces of it. Less easy is imagining a robot that could swim down one of the water volcanoes, wander the Enceladan Ocean making recordings and then swim back to the surface with its findings. It couldn't be built today. Twenty years down the line, maybe. There are certainly people alive today who will see such a device in operation someday.

This has set me to thinking about the possibility of extraterrestrial and extrasolar life in the universe. The search so far has been dominated by one honking big restriction: All we know about life is derived from a closely-related clutch of organisms existing on one lone planet.

So when we're looking for life, the first thing we do is look for water in liquid form. Because the kind of life we know requires it. Which is why all the emphasis has been on finding Earthlike planets in the "Goldilocks zone," where liquid water can exist on the surface.

But if life exists in Enceladus... or in Europa, which we're pretty sure also has an ocean tucked between its ice surface and rocky core... or in the ice satellites Ganymede, Callisto, Titan, Rhea, Titania, Oberon, Triton, Pluto, Eris, Sedna, or Orcus, all of which are speculated to have such oceans... then the possibility of life beyond the Solar System has just gone up tremendously.

And if life is found to exist in just one other planet in the Sun's entourage and if it can be demonstrated to have arisen independently, then we can confidently stare out into the night sky and see it everywhere.

Intelligent life, now, is a different matter. There's only the one intelligent species on our planet, and some of us have our doubts about that.

As for Enceladus, you can read the Guardian account here. Or the Wired article here.

*

The recent declaration that Enceladus has a small ocean under its icy shell immediately put a relatively obscure moon of Saturn on the forefront of the search for extraterrestrial life. Simply because it's easy to imagine sending a probe to collect fresh water-ice from the surface and examining the sample for microscopic life or traces of it. Less easy is imagining a robot that could swim down one of the water volcanoes, wander the Enceladan Ocean making recordings and then swim back to the surface with its findings. It couldn't be built today. Twenty years down the line, maybe. There are certainly people alive today who will see such a device in operation someday.

This has set me to thinking about the possibility of extraterrestrial and extrasolar life in the universe. The search so far has been dominated by one honking big restriction: All we know about life is derived from a closely-related clutch of organisms existing on one lone planet.

So when we're looking for life, the first thing we do is look for water in liquid form. Because the kind of life we know requires it. Which is why all the emphasis has been on finding Earthlike planets in the "Goldilocks zone," where liquid water can exist on the surface.

But if life exists in Enceladus... or in Europa, which we're pretty sure also has an ocean tucked between its ice surface and rocky core... or in the ice satellites Ganymede, Callisto, Titan, Rhea, Titania, Oberon, Triton, Pluto, Eris, Sedna, or Orcus, all of which are speculated to have such oceans... then the possibility of life beyond the Solar System has just gone up tremendously.

And if life is found to exist in just one other planet in the Sun's entourage and if it can be demonstrated to have arisen independently, then we can confidently stare out into the night sky and see it everywhere.

Intelligent life, now, is a different matter. There's only the one intelligent species on our planet, and some of us have our doubts about that.

As for Enceladus, you can read the Guardian account here. Or the Wired article here.

*

Published on April 04, 2014 08:46

April 3, 2014

Passage of Earth

.

I'm in e-print again! But before I say anything about that, I should apologize for not posting yesterday. Technically, I only ever explicitly promised to post on Fridays and Mondays, but I've been so consistent with Wednesdays that it's become a implicit promise. So I apologize.

So why did I miss yesterday? I was doing my taxes.

"Oh, you poor man," I hear you say. "Don't tell us about it."

Deal.

Anyway, my newest story, "Passage of Earth" is up at Clarkesworld . And I find myself at a loss as to how to describe it. If I tell you that a great deal of it is a detailed description of the autopsy of an alien worm, that might make the reading experience sound a bit more off-putting than I honestly believe it is. And if I tell you that a section of it reads very much like a horror story, that would be misleading as well. And if I try to tell you what classic story it most resembles ("like The Dunwich Horror, only with bunny rabbits," or "imagine Bears Discover Fire set on Mars and ending with the destruction of the universe"), I come up with nothing.

While I was writing "Passage of Earth" I thought it would end up in Analog . But then I came to the ending, and there were two obvious ways to conclude the story, neither of which I could bring myself to write. So I put it aside for a year or three, returning to it regularly to see what I could come up with. And finally, recently, the current ending came to me. It was one I didn't think I could sell to Trevor Quachri, but it pleased me enormously. So I sent it to Neil Clarke, he bought it, and now you can read the story online.

The story is free for the reading, and if you do, I hope you like it.

You can find the story here. Or you can just go to the magazine itself here and start poking around.

Above: Sunrise from Mars orbit, an image as beautiful as one of Chesley Bonestell's paintings. But it's a photograph! This is an era of greatness.

*

I'm in e-print again! But before I say anything about that, I should apologize for not posting yesterday. Technically, I only ever explicitly promised to post on Fridays and Mondays, but I've been so consistent with Wednesdays that it's become a implicit promise. So I apologize.

So why did I miss yesterday? I was doing my taxes.

"Oh, you poor man," I hear you say. "Don't tell us about it."

Deal.

Anyway, my newest story, "Passage of Earth" is up at Clarkesworld . And I find myself at a loss as to how to describe it. If I tell you that a great deal of it is a detailed description of the autopsy of an alien worm, that might make the reading experience sound a bit more off-putting than I honestly believe it is. And if I tell you that a section of it reads very much like a horror story, that would be misleading as well. And if I try to tell you what classic story it most resembles ("like The Dunwich Horror, only with bunny rabbits," or "imagine Bears Discover Fire set on Mars and ending with the destruction of the universe"), I come up with nothing.

While I was writing "Passage of Earth" I thought it would end up in Analog . But then I came to the ending, and there were two obvious ways to conclude the story, neither of which I could bring myself to write. So I put it aside for a year or three, returning to it regularly to see what I could come up with. And finally, recently, the current ending came to me. It was one I didn't think I could sell to Trevor Quachri, but it pleased me enormously. So I sent it to Neil Clarke, he bought it, and now you can read the story online.

The story is free for the reading, and if you do, I hope you like it.

You can find the story here. Or you can just go to the magazine itself here and start poking around.

Above: Sunrise from Mars orbit, an image as beautiful as one of Chesley Bonestell's paintings. But it's a photograph! This is an era of greatness.

*

Published on April 03, 2014 08:14

March 31, 2014

Geek Highways, Day 10: As Above, So Below

.

At last, Marianne and I reached Boston. Driving over the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge (also known as the Harvard Bridge), we had the opportunity to view the smoot marks originally created as a pointless student prank -- and probably the most famous such hack ever -- by (of course) frat boys from (where else?) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In October 1958, members of the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity had pledge Oliver R. Smoot lie down at one end of the bridge, marked his length with a line of paint, then had him lie down again at the line over and over again, to ultimately determine that the bridge was exactly 364.4 smoots long. There have surely been wittier pranks in the 66 years since, but this one caught the public imagination much as The Blob is celebrated long after better movies were forgotten. Exactly why will always be a matter of conjecture. But the smoot-marks are repainted every year and will doubtless continue to be repainted far into the foreseeable future.

Not far from the bridge we found the MIT Museum, where we met up with fantasist Greer Gilman, author of several core works of fantasy including the seminal novel Moonwise and, most recently, the Small Beer Press chapbook Cry Murder in a Small Press in which playwright Ben Jonson turns detective (and which, rather offhandedly, refutes the Oxfordians centuries before they appear). Together we three spent rather a lot of time before the collection of rare and historic slide rules, sharing reminiscences, before examining the other technology-related displays, including an informative series of student-made videos explaining how the Internet operates and why it's unlikely to ever do so satisfactorily (spoiler alert: no adult supervision). It's a small museum, but an engaging one.

On the second floor were some very choice robotics exhibits, and some very fine technology-based artworks. My favorites were Arthur Ganson's kinetic sculptures which, while limited to classical mechanics, were both witty and engaging. You can find three representative film clips here.

Less successful, alas, was the gallery of holographic art. A few years ago at the Chicago Worldcon, a writer friend told me he had just removed a 3-D picture from a new story because he'd realized that it was "fossil science fiction." Back in the 1960s, when holograms were invented, he explained, everybody assumed that the photographs and art of the future would be holographic. Now, it looks like they were a fad of the times and one that's rapidly fading into the past. "I was only including it because that's the sort of thing that used to be in science fiction and it's never really been purged. Hovercraft are another example of something that makes your story look instantly dated. And if you have a holograph of a hovercraft in your story, you've really go a problem."

The gallery was a fascinating glimpse back at a time when holography was going to be important someday. But that's all it was.

Down the block, we had a late lunch at Miracle of Science, a foodery so hip that it doesn't have a menu -- just a chalkboard in the shape of the periodic table, with the burgers and fajitas organized according to spurious principles of foodishness. There discussed Greer's upcoming publications and other matters of personal interest.

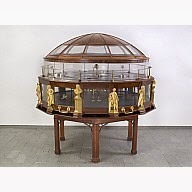

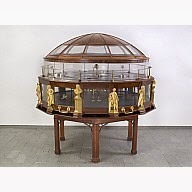

The afternoon was spent, at Greer's suggestion, at the Harvard Museum of Science & Culture, mostly

in their Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Perhaps the flashiest of which was the Grand Orery begun by Joseph Pope in 1776 and finally finished in 1785. Twelve-sided, domed, and featuring bronze figures of Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Bowdoin (then governor of Massachusetts) that were cast by Paul Revere, it's always been an almost pornographically prestigious piece of luxury goods.

in their Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Perhaps the flashiest of which was the Grand Orery begun by Joseph Pope in 1776 and finally finished in 1785. Twelve-sided, domed, and featuring bronze figures of Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Bowdoin (then governor of Massachusetts) that were cast by Paul Revere, it's always been an almost pornographically prestigious piece of luxury goods.

Here's part of the museum description:

There was a special display of historically significant autopsy-related tools and illustrations in a separate room. Ordinarily, the most amusing part of going to see such a display is my company, since I start out chipper and upbeat and by slow degrees turn a fetching shade of green. But this time, it was the plaster death-cast of the head of notorious "resurrection man" William Burke, carefully shaved bald as a billiard ball, because of Greer's crying out as she saw it, "But Burke has no hair!"

[If you don't get the joke, two minutes on Google will resolve your confusion.]

Finally, we left, weary from our travels, but happy, enlightened, and filled with a sense of the geekish wonder of the modern world. On the way out we passed the Mark I computer. Which was the use-name for the IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, a general purpose electro-mechanical computer employed for military purposes in the waning days of World War II.

As it was in the beginning, so it shall be at the end. I began this journey in Philadelphia with a visit to the first large-scale electronic computer, at the University of Pennsylvania. Now I ended it with a visit to one of the last large-scale electro-mechanical computers. The one was the beginning of an industry and an utterly changed world. The other was the culmination of mechanical computing, a dinosaur unaware that the rug was about to be pulled out from under its raison d'etre.

And so off to the home of friends for conversation and food and then sleep and then, ultimately, the long journey home.

Above: The Mark I. It continued in use until 1959.

*

At last, Marianne and I reached Boston. Driving over the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge (also known as the Harvard Bridge), we had the opportunity to view the smoot marks originally created as a pointless student prank -- and probably the most famous such hack ever -- by (of course) frat boys from (where else?) the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In October 1958, members of the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity had pledge Oliver R. Smoot lie down at one end of the bridge, marked his length with a line of paint, then had him lie down again at the line over and over again, to ultimately determine that the bridge was exactly 364.4 smoots long. There have surely been wittier pranks in the 66 years since, but this one caught the public imagination much as The Blob is celebrated long after better movies were forgotten. Exactly why will always be a matter of conjecture. But the smoot-marks are repainted every year and will doubtless continue to be repainted far into the foreseeable future.

Not far from the bridge we found the MIT Museum, where we met up with fantasist Greer Gilman, author of several core works of fantasy including the seminal novel Moonwise and, most recently, the Small Beer Press chapbook Cry Murder in a Small Press in which playwright Ben Jonson turns detective (and which, rather offhandedly, refutes the Oxfordians centuries before they appear). Together we three spent rather a lot of time before the collection of rare and historic slide rules, sharing reminiscences, before examining the other technology-related displays, including an informative series of student-made videos explaining how the Internet operates and why it's unlikely to ever do so satisfactorily (spoiler alert: no adult supervision). It's a small museum, but an engaging one.

On the second floor were some very choice robotics exhibits, and some very fine technology-based artworks. My favorites were Arthur Ganson's kinetic sculptures which, while limited to classical mechanics, were both witty and engaging. You can find three representative film clips here.

Less successful, alas, was the gallery of holographic art. A few years ago at the Chicago Worldcon, a writer friend told me he had just removed a 3-D picture from a new story because he'd realized that it was "fossil science fiction." Back in the 1960s, when holograms were invented, he explained, everybody assumed that the photographs and art of the future would be holographic. Now, it looks like they were a fad of the times and one that's rapidly fading into the past. "I was only including it because that's the sort of thing that used to be in science fiction and it's never really been purged. Hovercraft are another example of something that makes your story look instantly dated. And if you have a holograph of a hovercraft in your story, you've really go a problem."

The gallery was a fascinating glimpse back at a time when holography was going to be important someday. But that's all it was.

Down the block, we had a late lunch at Miracle of Science, a foodery so hip that it doesn't have a menu -- just a chalkboard in the shape of the periodic table, with the burgers and fajitas organized according to spurious principles of foodishness. There discussed Greer's upcoming publications and other matters of personal interest.

The afternoon was spent, at Greer's suggestion, at the Harvard Museum of Science & Culture, mostly

in their Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Perhaps the flashiest of which was the Grand Orery begun by Joseph Pope in 1776 and finally finished in 1785. Twelve-sided, domed, and featuring bronze figures of Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Bowdoin (then governor of Massachusetts) that were cast by Paul Revere, it's always been an almost pornographically prestigious piece of luxury goods.

in their Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Perhaps the flashiest of which was the Grand Orery begun by Joseph Pope in 1776 and finally finished in 1785. Twelve-sided, domed, and featuring bronze figures of Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Bowdoin (then governor of Massachusetts) that were cast by Paul Revere, it's always been an almost pornographically prestigious piece of luxury goods.Here's part of the museum description:

This gear-driven model of the solar system is made of mahogany and brass and is operated by hand-crank. The planets--Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn--are included with their known satellites. The planets revolve on their axes, the moons revolve around the planets, and each planetary system revolves around the sun at relative speeds. The Earth's system also shows the rotation of the lunar node, represented by a small ivory ball on a stick... Half-way through the project, Uranus was discovered (in 1781). Pope did not include this new planet.The rest of the collection is chockablock full of stuff that would drive your science-illiterate aunt mad with boredom, but which we three found endlessly fascinating -- including the control console from Harvard's cyclotron, which was ripped out on its final day of use (appropriately enough in 2001) and put on display, taped-up cartoons and all.

There was a special display of historically significant autopsy-related tools and illustrations in a separate room. Ordinarily, the most amusing part of going to see such a display is my company, since I start out chipper and upbeat and by slow degrees turn a fetching shade of green. But this time, it was the plaster death-cast of the head of notorious "resurrection man" William Burke, carefully shaved bald as a billiard ball, because of Greer's crying out as she saw it, "But Burke has no hair!"

[If you don't get the joke, two minutes on Google will resolve your confusion.]

Finally, we left, weary from our travels, but happy, enlightened, and filled with a sense of the geekish wonder of the modern world. On the way out we passed the Mark I computer. Which was the use-name for the IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, a general purpose electro-mechanical computer employed for military purposes in the waning days of World War II.

As it was in the beginning, so it shall be at the end. I began this journey in Philadelphia with a visit to the first large-scale electronic computer, at the University of Pennsylvania. Now I ended it with a visit to one of the last large-scale electro-mechanical computers. The one was the beginning of an industry and an utterly changed world. The other was the culmination of mechanical computing, a dinosaur unaware that the rug was about to be pulled out from under its raison d'etre.

And so off to the home of friends for conversation and food and then sleep and then, ultimately, the long journey home.

Above: The Mark I. It continued in use until 1959.

*

Published on March 31, 2014 00:30

March 28, 2014

Geek Highways, Day 9: The White Hot Heart of American Literary Heritage

.

Two literary households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Massachusetts, where we lay our scene...

North we drove to witch-haunted Salem. Here we sought out the childhood home of legendary editor and brilliant writer Gardner Dozois. That's it up above, at 18 Roslyn Street. Here's Gardner reminiscing, after I posted the picture on Facebook:

Which is indeed useful word for a future editor to have mastered early. But while he is likely to be best and deservedly remembered for his 19 years as Asimov 's, I value Gardner's fiction more. Back in the day, whenever Gardner had a party at his old apartment, Marianne would lurk by the table containing dozens -- or so it seemed -- of Hugo Awards for Best Editor. They were a terribly vulgar sight, like a display in a sex shop. But in among them, gleaming with virginal innocence were his two Nebulas for Best Short Fiction. Sooner or later, some young New York editorial type would say, "I didn't know Gardner was writer."

Then Marianne would smile and say, "Oh, yes. He's a much better writer than he is an editor.

Northward, ever northward we drove, to Gloucester where Virginia Lee Burton created her famous children's books and also her famous fabric prints. Marianne and I had been married several years before we chanced to find out that as children we had each particularly loved her book Mike Mulligan's Steam Shovel. I loved it because my name was Mike, just like the protagonist, and Marianne because the steam shovel's name was Marianne, just like her.

Some marriages are fated.

There are no public sites associated with Ms Burton today (her house is privately owned), but after quietly scoping out her old stomping grounds, Marianne and I drove west and south to Concord (properly pronounced, our New England friends tell us, "conquered"), where we found Walden Pond.

Preserving a site dedicated to simplicity and lack of ostentation as a tourist attraction inevitably makes it a magnet for irony. Parking at the site costs five dollars and the automated machine collecting the toll rejected my increasingly heated attempts to pay with first one credit card and then another. Eventually, I scraped together enough bills that the finicky device would accept and dropped by the information center. There I found a startling array of various editions of Walden, one for every purse, and some of them pricey indeed. So I bought the cut-price Dover paperback, cut through the parking lot, took a perfunctory look at the recreated hut (complete with a stand for the guest book), and when there was a break in the traffic hurried across the road to the pond.

Thoreau is known today for his anti-capitalist politics and for at least temporarily living the simple life he espoused. But what makes him geekworthy is that all the time he was at Walden Pond, he was practicing science, recording temperatures, and mapping the depth of the pond. For all that the literary establishment tries to make him respectable, he was one of us.

Down the road a way, we came at last to the second literary house of the day -- the Old Manse. Ralph Waldo Emerson's grandfather built the house, whose lands abutted the Old North Bridge, where the Shot Heard 'Round the World was fired, kicking off the American Revolution. Emerson grandpere witnessed the event from his fields. Two generations later, his grandson arranged for Nathaniel Hawthorne and his young bride to rent it. Emerson event sent Thoreau over to plant a garden for them, so they'd have flowers and vegetables awaiting them when they arrived.

There, the newlyweds scratched love-notes to each other on the windows and Nat wrote a fair amount of fantasy ( "Young Goodman Brown" ) and science fiction ( "Rappaccini's Daughter" ) there. The taint of genre runs deep in American literature, however hard the guardians of decency try to deny it.

Immediately above, the Old Manse. A holy spot for those of us who value America's contribution to world literature.

*

Two literary households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Massachusetts, where we lay our scene...

North we drove to witch-haunted Salem. Here we sought out the childhood home of legendary editor and brilliant writer Gardner Dozois. That's it up above, at 18 Roslyn Street. Here's Gardner reminiscing, after I posted the picture on Facebook:

The amazing thing is, it looks exactly the same as it did when I was a little kid in the '50s; it's even the same color. The neighborhood doesn't seem to have changed much either. We lived on the top floor, and it was sitting just inside that dormer window that's visible up there, which was the living room, with dusty sunlight coming in through that window, that I learned to read and read my first word, which, perhaps appropriately, was "No."

Which is indeed useful word for a future editor to have mastered early. But while he is likely to be best and deservedly remembered for his 19 years as Asimov 's, I value Gardner's fiction more. Back in the day, whenever Gardner had a party at his old apartment, Marianne would lurk by the table containing dozens -- or so it seemed -- of Hugo Awards for Best Editor. They were a terribly vulgar sight, like a display in a sex shop. But in among them, gleaming with virginal innocence were his two Nebulas for Best Short Fiction. Sooner or later, some young New York editorial type would say, "I didn't know Gardner was writer."

Then Marianne would smile and say, "Oh, yes. He's a much better writer than he is an editor.

Northward, ever northward we drove, to Gloucester where Virginia Lee Burton created her famous children's books and also her famous fabric prints. Marianne and I had been married several years before we chanced to find out that as children we had each particularly loved her book Mike Mulligan's Steam Shovel. I loved it because my name was Mike, just like the protagonist, and Marianne because the steam shovel's name was Marianne, just like her.

Some marriages are fated.

There are no public sites associated with Ms Burton today (her house is privately owned), but after quietly scoping out her old stomping grounds, Marianne and I drove west and south to Concord (properly pronounced, our New England friends tell us, "conquered"), where we found Walden Pond.

Preserving a site dedicated to simplicity and lack of ostentation as a tourist attraction inevitably makes it a magnet for irony. Parking at the site costs five dollars and the automated machine collecting the toll rejected my increasingly heated attempts to pay with first one credit card and then another. Eventually, I scraped together enough bills that the finicky device would accept and dropped by the information center. There I found a startling array of various editions of Walden, one for every purse, and some of them pricey indeed. So I bought the cut-price Dover paperback, cut through the parking lot, took a perfunctory look at the recreated hut (complete with a stand for the guest book), and when there was a break in the traffic hurried across the road to the pond.

Thoreau is known today for his anti-capitalist politics and for at least temporarily living the simple life he espoused. But what makes him geekworthy is that all the time he was at Walden Pond, he was practicing science, recording temperatures, and mapping the depth of the pond. For all that the literary establishment tries to make him respectable, he was one of us.

Down the road a way, we came at last to the second literary house of the day -- the Old Manse. Ralph Waldo Emerson's grandfather built the house, whose lands abutted the Old North Bridge, where the Shot Heard 'Round the World was fired, kicking off the American Revolution. Emerson grandpere witnessed the event from his fields. Two generations later, his grandson arranged for Nathaniel Hawthorne and his young bride to rent it. Emerson event sent Thoreau over to plant a garden for them, so they'd have flowers and vegetables awaiting them when they arrived.

There, the newlyweds scratched love-notes to each other on the windows and Nat wrote a fair amount of fantasy ( "Young Goodman Brown" ) and science fiction ( "Rappaccini's Daughter" ) there. The taint of genre runs deep in American literature, however hard the guardians of decency try to deny it.

Immediately above, the Old Manse. A holy spot for those of us who value America's contribution to world literature.

*

Published on March 28, 2014 15:34

March 26, 2014

Geek Highways, Day 8: The Day of Two Graves

.

How cool is this? I spent the morning at the Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT, writing. The truth be told, I paid for the privilege. But the fee was reasonable enough and it was, apparently, the first time the trustees had okayed such a thing. There were thirteen of us, nine women and four men -- this tells us something, though I don't know what -- and all of us were pretty obviously introverts. Not a lot of conversation, but some pretty serious scribbling and tapping.

The event took part in Mark Twain's library, which was, as you might expect, pretty opulent. I got perhaps a half-dozen pieces of flash fiction written and (via smartphone) a good start on an interview with an appropriate subject. More on both, as they mature.

Then Marianne picked me up and we jaunted over to Dinosaur State Park. There aren't a lot of dinosaur fossils in New England and most of what have been found there are trace fossils -- footprints, mostly. Which was the case here. The State of Connecticut was digging the foundation for a state building here, when a construction worker turned over a slab of rock and found dino footprints. Now, most of those found have been reburied, but a really nifty building was built over some of the better overlapping tracks and lights and other enhancements put in to help the casual viewer make sense of them.

Then off to Exeter, Rhode Island, where we sought out the grave of the vampire Mercy Brown. She was nothing of the sort, of course. But in the late nineteenth century, a local family died off one by one of consumption, arousing fears that a vampire was feeding upon them. The graves of another family were opened and the body of Mercy Brown, dead at age 19, was suspiciously fresh. (She'd died not long before the winter set in). So they cut out her heart, burned it, and fed the ashes in a glass of water, to the last surviving member of the consumptive family. Then they reinterred Ms Brown. Who turned out not to be a vampire after all, for her heart-ash did nothing to prevent the man from dying two months later.

It is speculated that Bram Stoker may have read accounts of the incident in the newspaper shortly before he wrote Dracula. But it is certain that H. P. Lovecraft knew the story, for he based "The Shunned House" on it.

The grave is clearly the most visited in the cemetery. There were pennies laid atop the stone and pebbles at its feet. People left offerings: a chain, an Army patch, a toenail clipper, and the like. And the earth before the grave was grassless and convex. More on which in a sec.

Our next stop, appropriately enough, was Providence, where Poe and Lovecraft both spent time in the cemetery (where, almost inexplicably, he did not write The Raven ) and where Lovecraft lived in and/or wrote about a bewildering array of buildings. I followed an itinerary which Darrell Schweitzer provided for me (and thoughtfully annotated), before dashing off to Swan Point Cemetery, where Lovecraft was buried. I was immediately struck by the fact that Lovecraft's name was engraved upon his parents' stately obelisk. So, while he didn't have a stone of his own, he wasn't exactly lying in an unmarked grave. Still, it was nice of his fans to chip in for a small personal stone.

At this grave too, people left offerings: coins, seashells, a bluebird's feather. Darrell tells me that the cemetery regularly clears away things left there. He also said some of them will dig up some of the dirt over the grave, apparently for magical purposes. Which cast a dark light on the grave of the unfortunate Mercy Brown. There's also a story that an attempt was made to dig up Lovecraft's body, after which it was reburied to one side of the stone -- so it might not even be where it's purported to lie.

On which somber note, we drove off to Massachusetts, where friends offered us place for the night. And so to bed.

*

How cool is this? I spent the morning at the Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT, writing. The truth be told, I paid for the privilege. But the fee was reasonable enough and it was, apparently, the first time the trustees had okayed such a thing. There were thirteen of us, nine women and four men -- this tells us something, though I don't know what -- and all of us were pretty obviously introverts. Not a lot of conversation, but some pretty serious scribbling and tapping.

The event took part in Mark Twain's library, which was, as you might expect, pretty opulent. I got perhaps a half-dozen pieces of flash fiction written and (via smartphone) a good start on an interview with an appropriate subject. More on both, as they mature.

Then Marianne picked me up and we jaunted over to Dinosaur State Park. There aren't a lot of dinosaur fossils in New England and most of what have been found there are trace fossils -- footprints, mostly. Which was the case here. The State of Connecticut was digging the foundation for a state building here, when a construction worker turned over a slab of rock and found dino footprints. Now, most of those found have been reburied, but a really nifty building was built over some of the better overlapping tracks and lights and other enhancements put in to help the casual viewer make sense of them.

Then off to Exeter, Rhode Island, where we sought out the grave of the vampire Mercy Brown. She was nothing of the sort, of course. But in the late nineteenth century, a local family died off one by one of consumption, arousing fears that a vampire was feeding upon them. The graves of another family were opened and the body of Mercy Brown, dead at age 19, was suspiciously fresh. (She'd died not long before the winter set in). So they cut out her heart, burned it, and fed the ashes in a glass of water, to the last surviving member of the consumptive family. Then they reinterred Ms Brown. Who turned out not to be a vampire after all, for her heart-ash did nothing to prevent the man from dying two months later.

It is speculated that Bram Stoker may have read accounts of the incident in the newspaper shortly before he wrote Dracula. But it is certain that H. P. Lovecraft knew the story, for he based "The Shunned House" on it.

The grave is clearly the most visited in the cemetery. There were pennies laid atop the stone and pebbles at its feet. People left offerings: a chain, an Army patch, a toenail clipper, and the like. And the earth before the grave was grassless and convex. More on which in a sec.

Our next stop, appropriately enough, was Providence, where Poe and Lovecraft both spent time in the cemetery (where, almost inexplicably, he did not write The Raven ) and where Lovecraft lived in and/or wrote about a bewildering array of buildings. I followed an itinerary which Darrell Schweitzer provided for me (and thoughtfully annotated), before dashing off to Swan Point Cemetery, where Lovecraft was buried. I was immediately struck by the fact that Lovecraft's name was engraved upon his parents' stately obelisk. So, while he didn't have a stone of his own, he wasn't exactly lying in an unmarked grave. Still, it was nice of his fans to chip in for a small personal stone.

At this grave too, people left offerings: coins, seashells, a bluebird's feather. Darrell tells me that the cemetery regularly clears away things left there. He also said some of them will dig up some of the dirt over the grave, apparently for magical purposes. Which cast a dark light on the grave of the unfortunate Mercy Brown. There's also a story that an attempt was made to dig up Lovecraft's body, after which it was reburied to one side of the stone -- so it might not even be where it's purported to lie.

On which somber note, we drove off to Massachusetts, where friends offered us place for the night. And so to bed.

*

Published on March 26, 2014 00:30

March 25, 2014

Geek Highways, Day 7: From Humbug to the Mesozoic

.

From the Empire State, Marianne and I drove eastward, into Connecticut. Bridgeport was home to Elias Howe, the inventor of the sewing machine and Harvey Hubbell, the inventor of (among other things) the electric plug and the pull-chain light socket. But its best-known citizen was the showman P. T. Barnum.

Barnum was the self-styled "King of Humbugs," and with good reason. He perpetuated and made good money off of such frauds as the Fiji Mermaid and the Cardiff Giant. But aside from such deceits, he was famous for giving the public good weight for their money. His shows and museums were chock-full of wonders, marvels, and things that people wanted to see.

So it's particularly sad that the Barnum Museum is still closed for repairs from damage caused by a tornado several years ago. I pressed my nose to the glass, marveled at the building's external decorations, and with a sigh moved on.

The day picked up, however, some miles down the interstate, Marianne spotted a sign for the Pez Information Center. Which is something we'd passed by many times over the decades en route to someplace else and never made the detour to. This time, we did -- and discovered that the spirit of P. T. Barnum is alive! Because the Center is that wet dream of capitalism, a gift shop that charges admission.

The admission was not expensive, however, and the PIC is in a low-key kind of way a hoot. There are a number of educational displays and a window overlooking a section of factory where, weekdays, Pez candies are made. But the chief attractions are the displays of classic Pez dispensers: Astronauts, American presidents, Halloween creatures, pretty much every Disney character ever put to film, and much, much more. It's a strangely charming experience to pause for half an hour to admire something as ephemeral and unimportant as a candy dispenser.

On the way out, I was tempted to buy the set of Pez dispensers immoralizing the cast of The Lord of the Rings. But I quickly came to my senses and a few minutes later was on my way to New Haven and the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. The Peabody is not a particularly large museum but it has a world-class collection and some of the most amazing fossils you'll ever have the pleasure to gawk at. Many of them were collected by legendary paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, today remembered almost as much for his fierce rivalry -- known as the "Bone Wars" -- with Edward Drinker Cope.

I could go on for hours about the wonders of the Peabody. But its crown jewel may well be the single most influential piece of scientific illustration ever, Rudolph Zallinger's 110 foot long mural, The Age of Reptiles. The mural covers all of the Mesozoic with plants and creatures from the earliest era, the Triassic, at the right-hand side under a dawn sky, the Jurassic in the center, and the Cretaceous at the left in the gathering dusk. A tremendous amount of information is encoded into the mural -- it took four and a half years to create -- and though some of the science has been superseded, that hardly matters.

What matters is that the mural created more scientists than will ever be tallied up. In the early 1950s, it was reproduced in Life magazine as a fold-out and millions of children were exposed to a vivid, engrossing vision of the prehistoric past at its most glamorous. Many, many paleontologists have testified that it was responsible for their choice of careers. Marianne tells me that it made her a scientist. And I'm sure it had a good deal to do with me becoming a science fiction writer. The importance of that single work of art cannot be exaggerated.

Years ago, I helped Robert Walters and Tess Kissinger put up the paleoart show at Dinofest. Among the astonishing paintings displayed there was the seven-foot-long cartoon for the mural. I was one of several people who carried the painting in, laid it down on the ground, and then undid the protective wrappings it had been shipped in. When it was revealed, we all knelt before it and bent down to examine its astonishing detail.

*

From the Empire State, Marianne and I drove eastward, into Connecticut. Bridgeport was home to Elias Howe, the inventor of the sewing machine and Harvey Hubbell, the inventor of (among other things) the electric plug and the pull-chain light socket. But its best-known citizen was the showman P. T. Barnum.

Barnum was the self-styled "King of Humbugs," and with good reason. He perpetuated and made good money off of such frauds as the Fiji Mermaid and the Cardiff Giant. But aside from such deceits, he was famous for giving the public good weight for their money. His shows and museums were chock-full of wonders, marvels, and things that people wanted to see.

So it's particularly sad that the Barnum Museum is still closed for repairs from damage caused by a tornado several years ago. I pressed my nose to the glass, marveled at the building's external decorations, and with a sigh moved on.

The day picked up, however, some miles down the interstate, Marianne spotted a sign for the Pez Information Center. Which is something we'd passed by many times over the decades en route to someplace else and never made the detour to. This time, we did -- and discovered that the spirit of P. T. Barnum is alive! Because the Center is that wet dream of capitalism, a gift shop that charges admission.

The admission was not expensive, however, and the PIC is in a low-key kind of way a hoot. There are a number of educational displays and a window overlooking a section of factory where, weekdays, Pez candies are made. But the chief attractions are the displays of classic Pez dispensers: Astronauts, American presidents, Halloween creatures, pretty much every Disney character ever put to film, and much, much more. It's a strangely charming experience to pause for half an hour to admire something as ephemeral and unimportant as a candy dispenser.

On the way out, I was tempted to buy the set of Pez dispensers immoralizing the cast of The Lord of the Rings. But I quickly came to my senses and a few minutes later was on my way to New Haven and the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. The Peabody is not a particularly large museum but it has a world-class collection and some of the most amazing fossils you'll ever have the pleasure to gawk at. Many of them were collected by legendary paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, today remembered almost as much for his fierce rivalry -- known as the "Bone Wars" -- with Edward Drinker Cope.

I could go on for hours about the wonders of the Peabody. But its crown jewel may well be the single most influential piece of scientific illustration ever, Rudolph Zallinger's 110 foot long mural, The Age of Reptiles. The mural covers all of the Mesozoic with plants and creatures from the earliest era, the Triassic, at the right-hand side under a dawn sky, the Jurassic in the center, and the Cretaceous at the left in the gathering dusk. A tremendous amount of information is encoded into the mural -- it took four and a half years to create -- and though some of the science has been superseded, that hardly matters.

What matters is that the mural created more scientists than will ever be tallied up. In the early 1950s, it was reproduced in Life magazine as a fold-out and millions of children were exposed to a vivid, engrossing vision of the prehistoric past at its most glamorous. Many, many paleontologists have testified that it was responsible for their choice of careers. Marianne tells me that it made her a scientist. And I'm sure it had a good deal to do with me becoming a science fiction writer. The importance of that single work of art cannot be exaggerated.

Years ago, I helped Robert Walters and Tess Kissinger put up the paleoart show at Dinofest. Among the astonishing paintings displayed there was the seven-foot-long cartoon for the mural. I was one of several people who carried the painting in, laid it down on the ground, and then undid the protective wrappings it had been shipped in. When it was revealed, we all knelt before it and bent down to examine its astonishing detail.

*

Published on March 25, 2014 00:30

Michael Swanwick's Blog

- Michael Swanwick's profile

- 546 followers

Michael Swanwick isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.