Michael Swanwick's Blog, page 150

May 21, 2014

Mea Culpa

.I have several deadlines going at once, so the usual Wednesday update will be made tomorrow instead of today.

I feel bad about this, but I made promises to editors and it's a matter of principle for me to keep such promises whenever I can.

*

I feel bad about this, but I made promises to editors and it's a matter of principle for me to keep such promises whenever I can.

*

Published on May 21, 2014 11:06

May 20, 2014

Voter Number 3

.I got up this morning, had coffee, read the newspaper, and then walked over to the polling place, which is at the high school this year.

I always defer to Marianne at the polls, which is how I wound up as Voter 3. Of course, it was a primary election -- and mostly a Commonwealth primary at that. (In Philadelphia, the primaries are important because the Democratic candidate always wins. So if you want a say in how the city is run, you register as a Democrat. I learned that my first year here, when I registered as an Independent.) Still, it's always sad when the turnout is low.

Me, I always vote. Sometimes it's hard to figure out who to vote for. Sometimes I have to scramble to find someone to vote against. But patriots died to give me this privilege and I take it very seriously indeed. The president of the NRA is going to say, "Take my guns away -- I don't want 'em!" long before they manage to pry the ballot out of my cold, dead fingers.

Afterward, Marianne and I went to Bob's Diner for breakfast. I had an eggamuffin with scrapple, hash browns on the side, coffee, and orange juice. Bob's serves up hash browns and scrapple both with a nice crusty surface. So I headed home in a happy mood and ready to work.

*

I always defer to Marianne at the polls, which is how I wound up as Voter 3. Of course, it was a primary election -- and mostly a Commonwealth primary at that. (In Philadelphia, the primaries are important because the Democratic candidate always wins. So if you want a say in how the city is run, you register as a Democrat. I learned that my first year here, when I registered as an Independent.) Still, it's always sad when the turnout is low.

Me, I always vote. Sometimes it's hard to figure out who to vote for. Sometimes I have to scramble to find someone to vote against. But patriots died to give me this privilege and I take it very seriously indeed. The president of the NRA is going to say, "Take my guns away -- I don't want 'em!" long before they manage to pry the ballot out of my cold, dead fingers.

Afterward, Marianne and I went to Bob's Diner for breakfast. I had an eggamuffin with scrapple, hash browns on the side, coffee, and orange juice. Bob's serves up hash browns and scrapple both with a nice crusty surface. So I headed home in a happy mood and ready to work.

*

Published on May 20, 2014 09:37

May 19, 2014

The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead

.

Avram Davidson was, poor bastard, one of the greatest American short story writers of the Twentieth Century, an achievement not unrelated to the fact that he died in poverty. To make matters worse, he was also a master of the discursive essay, an art form whose monetary return per hour spent on research makes short fiction, and possibly even poetry, seem lucrative by comparison.

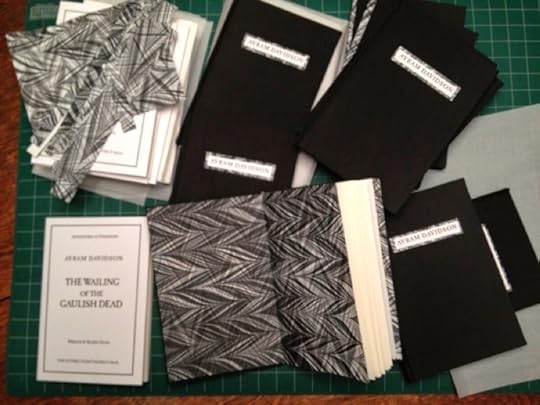

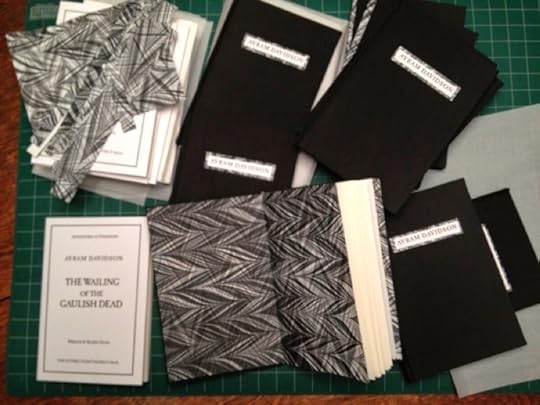

So when Davidson wrote The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead , unpublished in his lifetime, almost lost after his demise, preserved in a single typescript copy by collector Iain Odlin, and now available from the Avram Davidson Society and the Nutmeg Point District Mail as a limited edition handsome crafted hardcover with a cogent and lucid introduction by Eileen Gunn, there was no incentive for him to write to please anybody but himself. His late prose style, legendarily daunting, is to be found here in early blossom. This is a typical sample:

Time and again I have found that “even when I do not seek, I find” – serendipitythis may be called, it being understood that what one finds is found while seeking something else – not always, alas, but often, often, often: once one has determined to find something out, it will find itself out for you. Often. To invent an example, suppose that you have become interested in butterflies as articles of human clothing. You may find information under butterflies, you may find it under clothing; then again, you may not. The matter may be half-abandoned, half-forgotten . . . for a while. And then, without a thought in the world as regards butterflies as articles of human clothing, casually you begin a book about – say – Virginia Woolf. And there, on pages 27 and 28, you find yourself reading, as it might be, that Virginia Woolf’s eccentric cousin Algernon Stephen as a young man spent a year in Fantaanango, a country in the Central Indies where to his astonishment he found the natives adorning their clothing with the wings of gorgeous butterflies. In one of his frequent letters home, he wrote . . . .And so on.I repeat: this example is fictitious.

Now, either that oft-reworked, cunningly crafted sort of prose appeals to you or it does not, and if it does not you might as well keep on moving down the midway where there are booths galore catering to your particular tastes. But for those few – those “happy few,” as the Bard would have it – who can savor the great man at his most Davidsonian – surely there are enough of us to sell out this edition of 200, though the text of the essay is only 37 pages long and it costs $25.00 plus postage – there is only one place to get it. This essay is one of a series, almost all of which were collected in the Owlswick Press collection, Adventures in Unhistory (later reprinted by Tor Books). But where those others largely explored the origins and lore of various supernatural creatures, The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead deals with… well, to say exactly what it is about would be to give away the essay’s conclusion. Davidson began with a phrase, apparently his own, which popped into his head one day and which serves as the title of the essay. Intrigued, he set out to discover exactly what he meant by it. Thus begins a voyage through the mind of a brilliant autodidact, a man who engaged in esoteric research not for profit or academic survival but simply for the fun of it. Those who can enjoy such company on a journey with no obvious direction or destination know who they are. Others, as I said, should keep moving. I witnessed a reader reach the end of this essay and burst into delighted laughter.

And . . .

You can find the ordering page for the book here.

Above: An image of the binding of the book taken from the Avram Davidson Society ordering page. The review first appeared in The New York Review of Science Fiction and is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick.

*

Avram Davidson was, poor bastard, one of the greatest American short story writers of the Twentieth Century, an achievement not unrelated to the fact that he died in poverty. To make matters worse, he was also a master of the discursive essay, an art form whose monetary return per hour spent on research makes short fiction, and possibly even poetry, seem lucrative by comparison.

So when Davidson wrote The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead , unpublished in his lifetime, almost lost after his demise, preserved in a single typescript copy by collector Iain Odlin, and now available from the Avram Davidson Society and the Nutmeg Point District Mail as a limited edition handsome crafted hardcover with a cogent and lucid introduction by Eileen Gunn, there was no incentive for him to write to please anybody but himself. His late prose style, legendarily daunting, is to be found here in early blossom. This is a typical sample:

Time and again I have found that “even when I do not seek, I find” – serendipitythis may be called, it being understood that what one finds is found while seeking something else – not always, alas, but often, often, often: once one has determined to find something out, it will find itself out for you. Often. To invent an example, suppose that you have become interested in butterflies as articles of human clothing. You may find information under butterflies, you may find it under clothing; then again, you may not. The matter may be half-abandoned, half-forgotten . . . for a while. And then, without a thought in the world as regards butterflies as articles of human clothing, casually you begin a book about – say – Virginia Woolf. And there, on pages 27 and 28, you find yourself reading, as it might be, that Virginia Woolf’s eccentric cousin Algernon Stephen as a young man spent a year in Fantaanango, a country in the Central Indies where to his astonishment he found the natives adorning their clothing with the wings of gorgeous butterflies. In one of his frequent letters home, he wrote . . . .And so on.I repeat: this example is fictitious.

Now, either that oft-reworked, cunningly crafted sort of prose appeals to you or it does not, and if it does not you might as well keep on moving down the midway where there are booths galore catering to your particular tastes. But for those few – those “happy few,” as the Bard would have it – who can savor the great man at his most Davidsonian – surely there are enough of us to sell out this edition of 200, though the text of the essay is only 37 pages long and it costs $25.00 plus postage – there is only one place to get it. This essay is one of a series, almost all of which were collected in the Owlswick Press collection, Adventures in Unhistory (later reprinted by Tor Books). But where those others largely explored the origins and lore of various supernatural creatures, The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead deals with… well, to say exactly what it is about would be to give away the essay’s conclusion. Davidson began with a phrase, apparently his own, which popped into his head one day and which serves as the title of the essay. Intrigued, he set out to discover exactly what he meant by it. Thus begins a voyage through the mind of a brilliant autodidact, a man who engaged in esoteric research not for profit or academic survival but simply for the fun of it. Those who can enjoy such company on a journey with no obvious direction or destination know who they are. Others, as I said, should keep moving. I witnessed a reader reach the end of this essay and burst into delighted laughter.

And . . .

You can find the ordering page for the book here.

Above: An image of the binding of the book taken from the Avram Davidson Society ordering page. The review first appeared in The New York Review of Science Fiction and is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick.

*

Published on May 19, 2014 06:24

May 16, 2014

Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons, Blurbs & Reviews

.

As always, I'm on the road again. But in my absence, good news...

Tom Purdom, who has been writing and publishing science fiction for over fifty years -- the number of people who can make that claim constitute a very small and illustrious club -- has just started getting reviews for his first collection, Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons, published by Fantastic Books.

But before I get to that, let me once again share with you the blurbs that I and some of of Tom's other admirers gave his book:

That's what we said. But how would people who were not necessarily admirers of the man's work for many decades respond?

Well . . . Over at Analog , reviewer Don Sakers said, "The twelve SF stories in Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons are a perfect blend of really cool ideas and believable, sympathetic characters. Beyond that, Purdom doesn’t shy away from exploring the moral and ethical choices of his characters.... Definitely recommended."

Andrew Andrews at True Review summed up the book by saying, "Tom Purdom has assembled a great collection of tales."

And a medley of reviewers at Library Thing wrote things like:

"Before receiving this book I had never heard of Tom Purdom but I’m very glad that I have now. All of his stories, no matter how out there and fantastic they are have a solid, grounded feeling to them, you are reading about real people with real motivations and even when the characters or situations are completely alien they are relatable."

And:

"Purdom writes about characters; while there is obviously a science fictional basis for every story, the primary point is how the characters relate to one another. Frequently one or more of those characters have modifications that make them behave in a certain way emotionally or physically, and the point of the story is to examine how they interact with other, unmodified people."

And:

"I've enjoyed Tom Purdom's stories over the past few years as they've appeared in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, with which I struggle to keep up. However, this volume gives me a much stronger sense of him as a writer, and a much stronger sense of his -- heretofore unrealized by me -- admirable range. Prior to reading this book I would have characterized him as an enjoyable creator of alien races, but someone you would read and like and quickly move on from, rather than as a writer you would actively seek out for another throat-grab. This book has changed my mind. In a rare occurrence, the blurbs on the back cover of Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons are true: Tom Purdom is seriously underrated. He was underrated by me, for one. "

And:

"There are several other outstanding Purdom works that could have been included in this book. For now, this is a good start in recognizing a writer too long ignored. Every one of these stories, first published in Asimov’s Science Fiction from 1992 to 2012, is worth reading."

And, most succinctly:

"If you like science fiction you will probably like this book."

So why do I share these reviews with you at such length? Simply because it gives me the opportunity to say something I've been waiting forever to write:

Told you so.

You can read the Analog review here, the one from True Review here, and the Library Thing reviews here.

And speaking of Catherine Asaro . . .

I've just heard from everybody's favorite purveyor of romance-and-hard-science SF novels that she's launched a Kickstarter campaign for her science fiction collection Aurora in Four Voices . This was a limited-edition small press book containing five stories and novellas (the title comes from a Hugo and Nebula nominated novella) including the Nebula winning "Spacetime Pool," plus an essay on Catherine's use of mathematics in her fiction.

Technically, the book isn't unavailable -- ABE has one copy listed for seventy dollars plus shipping from the UK. But if you'er a fan of Catherine Asaro and don't already have a copy, the audiobook is probably your best shot.

You can find the project here. It looks to be doing well.

*

As always, I'm on the road again. But in my absence, good news...

Tom Purdom, who has been writing and publishing science fiction for over fifty years -- the number of people who can make that claim constitute a very small and illustrious club -- has just started getting reviews for his first collection, Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons, published by Fantastic Books.

But before I get to that, let me once again share with you the blurbs that I and some of of Tom's other admirers gave his book:

"Very simply, Tom Purdom IS science fiction. His ever-inventive stories are cut from the cloth of it and sewn with the skill of a master." —Gregory Frost

"Tom Purdom made his first professional sale all the way back in 1957. It's hard to think of any other member of his generation whose current work is frequently mentioned in the same breath with that of writers such as Charles Stross, Greg Egan, and Alastair Reynolds, many of whom were not even born when Tom started his professional career, but Tom's is. In fact, for sweep and audacity of imagination and a wealth of new ideas and dazzling conceptualization, Tom Purdom not only holds his own with the New Young Turks of the '90s and the Oughts, he sometimes surpasses them. And unlike some of today's Hot New Writers, Tom's work never fails to ALSO feature fascinating and psychologically complex characters, and intrepid investigation into the human heart." —Gardner Dozois

"Tom Purdom is the most underrated science fiction writer I know of. His short fiction delivers again and again with great plots, characters, and an imagination both cosmic and delicately complex." —Jeffrey Ford

"Purdom has created a major body of work. Thoughtful, humane, intelligent, extrapolative, involving, his stories are exactly the sort of thing our genre exists to make possible. If you don't like Tom Purdom, you don't like science fiction. Period." —Michael Swanwick

That's what we said. But how would people who were not necessarily admirers of the man's work for many decades respond?

Well . . . Over at Analog , reviewer Don Sakers said, "The twelve SF stories in Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons are a perfect blend of really cool ideas and believable, sympathetic characters. Beyond that, Purdom doesn’t shy away from exploring the moral and ethical choices of his characters.... Definitely recommended."

Andrew Andrews at True Review summed up the book by saying, "Tom Purdom has assembled a great collection of tales."

And a medley of reviewers at Library Thing wrote things like:

"Before receiving this book I had never heard of Tom Purdom but I’m very glad that I have now. All of his stories, no matter how out there and fantastic they are have a solid, grounded feeling to them, you are reading about real people with real motivations and even when the characters or situations are completely alien they are relatable."

And:

"Purdom writes about characters; while there is obviously a science fictional basis for every story, the primary point is how the characters relate to one another. Frequently one or more of those characters have modifications that make them behave in a certain way emotionally or physically, and the point of the story is to examine how they interact with other, unmodified people."

And:

"I've enjoyed Tom Purdom's stories over the past few years as they've appeared in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, with which I struggle to keep up. However, this volume gives me a much stronger sense of him as a writer, and a much stronger sense of his -- heretofore unrealized by me -- admirable range. Prior to reading this book I would have characterized him as an enjoyable creator of alien races, but someone you would read and like and quickly move on from, rather than as a writer you would actively seek out for another throat-grab. This book has changed my mind. In a rare occurrence, the blurbs on the back cover of Lovers & Fighters, Starships & Dragons are true: Tom Purdom is seriously underrated. He was underrated by me, for one. "

And:

"There are several other outstanding Purdom works that could have been included in this book. For now, this is a good start in recognizing a writer too long ignored. Every one of these stories, first published in Asimov’s Science Fiction from 1992 to 2012, is worth reading."

And, most succinctly:

"If you like science fiction you will probably like this book."

So why do I share these reviews with you at such length? Simply because it gives me the opportunity to say something I've been waiting forever to write:

Told you so.

You can read the Analog review here, the one from True Review here, and the Library Thing reviews here.

And speaking of Catherine Asaro . . .

I've just heard from everybody's favorite purveyor of romance-and-hard-science SF novels that she's launched a Kickstarter campaign for her science fiction collection Aurora in Four Voices . This was a limited-edition small press book containing five stories and novellas (the title comes from a Hugo and Nebula nominated novella) including the Nebula winning "Spacetime Pool," plus an essay on Catherine's use of mathematics in her fiction.

Technically, the book isn't unavailable -- ABE has one copy listed for seventy dollars plus shipping from the UK. But if you'er a fan of Catherine Asaro and don't already have a copy, the audiobook is probably your best shot.

You can find the project here. It looks to be doing well.

*

Published on May 16, 2014 00:30

May 15, 2014

There Is No Hope. I Choose To Hope.

.Let me start by observing that every single human being I know -- and this emphatically includes conservatives -- is AGAINST kidnapping schoolgirls and selling them into slavery. Are you nuts? Of COURSE they are.

Of course we are.

Yet some self-identified "conservative" pundits have been mocking the hashtag bringbackourgirls thing, asking what material good it does. To them I have only this to say: moved by the umpteenth hundredth TV article about this, I just made a donation to Anti-Slavery International. It's not much. But it's something.

Anti-Slavery International is, at 175 years, the oldest anti-slavery organization in the world. It is a disgrace that they are still in existence. You can donate money to them here.

Let's do our small bit to put this organization out of business.

*

Of course we are.

Yet some self-identified "conservative" pundits have been mocking the hashtag bringbackourgirls thing, asking what material good it does. To them I have only this to say: moved by the umpteenth hundredth TV article about this, I just made a donation to Anti-Slavery International. It's not much. But it's something.

Anti-Slavery International is, at 175 years, the oldest anti-slavery organization in the world. It is a disgrace that they are still in existence. You can donate money to them here.

Let's do our small bit to put this organization out of business.

*

Published on May 15, 2014 07:25

May 14, 2014

Our Inadequately Understood Universe

.

Here's quite a nice overview of the computer model built at MIT to recreate thirteen billion years of the evolution of the universe.

Very pretty stuff.

But more and more I find myself thinking of celestial spheres. In classical times it was thought that the stars all rested on the surface of a sphere. The complex motions of the planets were explained by assuming that each was embedded in its own, independently moving transparent sphere. (Made of quintessence -- but let's not go there today.)

This system worked well enough, particularly after Copernicus placed the Sun at the center of everything. But only just well enough. As the measurements of planetary orbits got better and better, deviance from predicted results had to be explained away. To the orderly cycles were added epicycles and eccentrics. Angels were recruited to keep the things spinning. The machinery kept getting more and more complicated.

Meanwhile, troublemakers like Tycho Brahe discovered that comets passed effortlessly through these supposedly crystal spheres.

It wasn't until Johannes Kepler scrapped the entire system (well, almost all -- he kept the outermost celestial sphere so the stars would have a place to perch on) in favor of celestial mechanics that it all made sense again.

So every time I hear about the necessity of dark matter to make the numbers line up right, or the need for dark energy to explain observed phenomena, or that the rate of expansion for the universe is speeding up, or that in the early stages of cosmic evolution the whole shebang moved faster than the speed of light, or that "Einstein's greatest blunder," the cosmological constant, has been yet again added to or subtracted from our understanding of the Way Things Are . . .

Well. I just have to wonder if we're not missing something very simple and counterintuitive.

After all, how can the planets keep from falling down if they're not embedded in crystal spheres?

And . . .

Stephen Notley, the cartoonist-creator of Bob the Angry Flower did a much more succinct critique of the currently accepted model of cosmology in a cartoon titled CREATION: A Science Story . You can find it here.

*

Here's quite a nice overview of the computer model built at MIT to recreate thirteen billion years of the evolution of the universe.

Very pretty stuff.

But more and more I find myself thinking of celestial spheres. In classical times it was thought that the stars all rested on the surface of a sphere. The complex motions of the planets were explained by assuming that each was embedded in its own, independently moving transparent sphere. (Made of quintessence -- but let's not go there today.)

This system worked well enough, particularly after Copernicus placed the Sun at the center of everything. But only just well enough. As the measurements of planetary orbits got better and better, deviance from predicted results had to be explained away. To the orderly cycles were added epicycles and eccentrics. Angels were recruited to keep the things spinning. The machinery kept getting more and more complicated.

Meanwhile, troublemakers like Tycho Brahe discovered that comets passed effortlessly through these supposedly crystal spheres.

It wasn't until Johannes Kepler scrapped the entire system (well, almost all -- he kept the outermost celestial sphere so the stars would have a place to perch on) in favor of celestial mechanics that it all made sense again.

So every time I hear about the necessity of dark matter to make the numbers line up right, or the need for dark energy to explain observed phenomena, or that the rate of expansion for the universe is speeding up, or that in the early stages of cosmic evolution the whole shebang moved faster than the speed of light, or that "Einstein's greatest blunder," the cosmological constant, has been yet again added to or subtracted from our understanding of the Way Things Are . . .

Well. I just have to wonder if we're not missing something very simple and counterintuitive.

After all, how can the planets keep from falling down if they're not embedded in crystal spheres?

And . . .

Stephen Notley, the cartoonist-creator of Bob the Angry Flower did a much more succinct critique of the currently accepted model of cosmology in a cartoon titled CREATION: A Science Story . You can find it here.

*

Published on May 14, 2014 07:40

May 12, 2014

Portrait of the Artist on Adolf Hitler's Birthday

.

The following is a short story review. Enjoy!

Kim Stanley Robinson’s story is both a careful establishment of the context for this concert (it was a command performance, and one which Furtwangler had been ducking for years) and a close reading of the emotional text of the interpretation – exactly what Furtwangler meant by it – as mediated by an ordinary man who happens to be the orchestra’s timpanist.

Line by line, paragraph by page, Robinson has never written better than here.

That said, it must be mentioned that “The Timpanist of the Berlin Philharmonic, 1942” is not by any reading a work of science fiction or fantasy. However, a perceptive reader will easily tell that this is a mainstream story written by a writer forged in genre. For a very long time the consensus model for non-genre fiction (but there are signs that this may be changing) has been one where the events serve to illuminate the inner life of its main character. Not so here. The timpanist is a perfectly convincing creation, but he is also, except for his profession, one whose character is neither central to the story nor revealed by its end. Rather, Robinson uses events to make a larger statement – about art, about history, about culture. You can decide on the specifics for yourself. It is a work of art that looks outward, rather than inward.

Were this science fiction, it would be easily one of the best SF stories of its year. As it stands, it is simply one of the best stories of its year.

Need I say period? Very well, then. Period.

This review first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction and is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick.

*

The following is a short story review. Enjoy!

Kim Stanley Robinson’s story is both a careful establishment of the context for this concert (it was a command performance, and one which Furtwangler had been ducking for years) and a close reading of the emotional text of the interpretation – exactly what Furtwangler meant by it – as mediated by an ordinary man who happens to be the orchestra’s timpanist.

Line by line, paragraph by page, Robinson has never written better than here.

That said, it must be mentioned that “The Timpanist of the Berlin Philharmonic, 1942” is not by any reading a work of science fiction or fantasy. However, a perceptive reader will easily tell that this is a mainstream story written by a writer forged in genre. For a very long time the consensus model for non-genre fiction (but there are signs that this may be changing) has been one where the events serve to illuminate the inner life of its main character. Not so here. The timpanist is a perfectly convincing creation, but he is also, except for his profession, one whose character is neither central to the story nor revealed by its end. Rather, Robinson uses events to make a larger statement – about art, about history, about culture. You can decide on the specifics for yourself. It is a work of art that looks outward, rather than inward.

Were this science fiction, it would be easily one of the best SF stories of its year. As it stands, it is simply one of the best stories of its year.

Need I say period? Very well, then. Period.

This review first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction and is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick.

*

Published on May 12, 2014 07:35

May 7, 2014

Samuel R. Delany and Me at the Joyce Kilmer Service Area, March 2005

.

Not all things we are nostalgic for should be preserved. I personally feel a sense of loss for the chatty intros that science fiction collections used to have before each story, explaining how they came to be. Chiefly this is because back when I was a teenage werewolf, I studied those intros carefully, gleaning tiny crumbs of writing lore that the Great Authors would occasionally inadvertently let drop. But also because any extinct or near-extinct prose form is to be lamented.

The late, great, and greatly missed editor Jim Turner sternly informed me on the occasion of my first collection ( Gravity's Angels , Arkham House), that such intros were a self indulgence which he would not put up with, and in my experience in matters editorial Jim was inevitably right. So that's settled.

Nevertheless, the one regret I have regarding Eileen Gunn's exemplary new collection, Questionable Practices (her second! and this one only took ten years! she's definitely getting faster!) is that it isn't fat and unwieldy with intros, outros, afterwords and story notes. So I'm going to provide one for her -- and it's not even for one of the stories we co-wrote!

"Michael Swanwick and Samuel R. Delany at the Joyce Kilmer Service Area, March 2005"

Living on opposite coasts as we do, Eileen and I don't get to spend much time together. But when we do get together we have some very intense conversations because for unknown reasons she is one of the few people with whom I can talk seriously and at length about writing.

So it was sometime in 2005 and Eileen and I were sitting on the porch of a house high up on the slopes of San Francisco, watching the sun set and then green rivers of fog rolling down from the mountains. We spoke of many things. It would amaze most of my friends to hear that I didn't make a single joke.

Not long before, for reasons of plot irrelevant to this narrative, I had driven Chip Delany from Philadelphia to New York City. He needed a ride and I was happy to be able to help him out. So, along with many other matters, I told Eileen about the quite interesting conversation we had. (I betrayed no confidences in doing so, because it wasn't a confidential kind of conversation -- we were discussing facts and ideas.) One thing I shared was Chip's explanation of the virtues of Guy Davenport's short fiction. Davenport was a critic of dazzling lucidity. But in his fiction he wrote for a small and rarefied audience -- and the point of much of his work relied on the reader knowing specific information (in the story in question, it was of a lacuna in Kafka's biography) that was not contained in the story.

Why on earth Eileen should decide to write a Guy Davenportly story about that journey, I have not the slightest notion. But she did. Sometimes a writer's brain catches fire with the desire to write something for which there is no explanation.

The story is, as the subtitle puts it, OUTPUT FROM A NOSTALGIC, IF SOMEWHAT MISINFORMED, GUYDAVENPORT STORYBOT, IN THE YEAR 2115. Much of what is written is deliberately not so. It's Eileen who knows to say "Nyemnoshka," when asked if she has any Russian, not I. But bits of it are factual, though I'm not going to tell you which.

Save for one. When I said, "I'm a burger kind of guy," the white-bearded semiotician really did reply, "So am I."

So there we are, Chip and I, the two most ordinary guys you'll ever meet in the Joyce Kilmer Service Area.

I forget whose place that was where we had the conversation. I know that Eileen was house-sitting for someone. I have a nagging suspicion that it might have been Ellen Klages. If so, I just want to say to Ellen that I was the one who turned around all the little figurines on the fireplace mantle. Eileen had nothing to do with it.

Much.

*

Not all things we are nostalgic for should be preserved. I personally feel a sense of loss for the chatty intros that science fiction collections used to have before each story, explaining how they came to be. Chiefly this is because back when I was a teenage werewolf, I studied those intros carefully, gleaning tiny crumbs of writing lore that the Great Authors would occasionally inadvertently let drop. But also because any extinct or near-extinct prose form is to be lamented.

The late, great, and greatly missed editor Jim Turner sternly informed me on the occasion of my first collection ( Gravity's Angels , Arkham House), that such intros were a self indulgence which he would not put up with, and in my experience in matters editorial Jim was inevitably right. So that's settled.

Nevertheless, the one regret I have regarding Eileen Gunn's exemplary new collection, Questionable Practices (her second! and this one only took ten years! she's definitely getting faster!) is that it isn't fat and unwieldy with intros, outros, afterwords and story notes. So I'm going to provide one for her -- and it's not even for one of the stories we co-wrote!

"Michael Swanwick and Samuel R. Delany at the Joyce Kilmer Service Area, March 2005"

Living on opposite coasts as we do, Eileen and I don't get to spend much time together. But when we do get together we have some very intense conversations because for unknown reasons she is one of the few people with whom I can talk seriously and at length about writing.

So it was sometime in 2005 and Eileen and I were sitting on the porch of a house high up on the slopes of San Francisco, watching the sun set and then green rivers of fog rolling down from the mountains. We spoke of many things. It would amaze most of my friends to hear that I didn't make a single joke.

Not long before, for reasons of plot irrelevant to this narrative, I had driven Chip Delany from Philadelphia to New York City. He needed a ride and I was happy to be able to help him out. So, along with many other matters, I told Eileen about the quite interesting conversation we had. (I betrayed no confidences in doing so, because it wasn't a confidential kind of conversation -- we were discussing facts and ideas.) One thing I shared was Chip's explanation of the virtues of Guy Davenport's short fiction. Davenport was a critic of dazzling lucidity. But in his fiction he wrote for a small and rarefied audience -- and the point of much of his work relied on the reader knowing specific information (in the story in question, it was of a lacuna in Kafka's biography) that was not contained in the story.

Why on earth Eileen should decide to write a Guy Davenportly story about that journey, I have not the slightest notion. But she did. Sometimes a writer's brain catches fire with the desire to write something for which there is no explanation.

The story is, as the subtitle puts it, OUTPUT FROM A NOSTALGIC, IF SOMEWHAT MISINFORMED, GUYDAVENPORT STORYBOT, IN THE YEAR 2115. Much of what is written is deliberately not so. It's Eileen who knows to say "Nyemnoshka," when asked if she has any Russian, not I. But bits of it are factual, though I'm not going to tell you which.

Save for one. When I said, "I'm a burger kind of guy," the white-bearded semiotician really did reply, "So am I."

So there we are, Chip and I, the two most ordinary guys you'll ever meet in the Joyce Kilmer Service Area.

I forget whose place that was where we had the conversation. I know that Eileen was house-sitting for someone. I have a nagging suspicion that it might have been Ellen Klages. If so, I just want to say to Ellen that I was the one who turned around all the little figurines on the fireplace mantle. Eileen had nothing to do with it.

Much.

*

Published on May 07, 2014 13:16

May 5, 2014

The Two Faces of Andy Duncan's Close Encounters!

.

Did you know? A run of the mill paperback science fiction or fantasy novel will typically get more and longer reviews than a story that wins both the Hugo and Nebula awards. That's why when I can find the time -- and more and more, I have so much on my plate that I can't find the time, alas -- I write reviews of particularly splendid exemplars of short fiction and publish them in the New York Review of Science Fiction.

A little over a month ago, I reviewed three works of fiction and an essay there, and it occurred to me to share them, one at a time, over the next few weeks. Here's the first:

Andy Duncan, of whose work one can predict nothing save that it will be beautifully written, has produced what is, even for him, a genuine oddity in “Close Encounters,” a story which originally appeared in his 2012 collection, The Pottawattomie Giant and Other Stories (PS Publishing), was subsequently reprinted in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and two separate best of the year anthologies, and went on to win the Nebula Award for Best Novelette. It is at one and the same time two distinct stories, one of them very good indeed and the other much better than that. “Close Encounters” is narrated by Buck Nelson, a crusty Ozarks farmer in his eightieth-odd year. In his youth he wrote a book about his adventures with a space alien named Bob Solomon, who took him to the Moon, Mars, and Venus, and gave him a giant dog named Bo. For years after that, Buck threw an annual for-profit picnic on his farm for UFO enthusiasts. But now he is a bitter old man, dodging the dwindling number of reporters who occasionally seek him out, and mulling over the disappointments of his life. As always when Duncan is playing with Southern rhythms, the prose sparkles. Here’s Buck’s reply, when asked by a stringer for the Associated Press why he stopped the picnics and started running visitors off with a shotgun:

Prose that good is its own justification, and Buck presents a strong argument for the superiority of Romance, however tawdry, over mere reality. But straight talker though he seems to be, the old man is hiding something. For most of the first half of “Close Encounters,” the question of whether Buck lied about the Space Brothers in order to get attention and make a little money on the side is left open. But then at mid-point, he opens up to the reader about “. . . the real reason I give up on the picnics, turned sour on the whole flying-saucer industry, and kept close to the willows ever since. It warn’t my damn lumbago or the Mothman or Barney and Betty Hill and their Romper Room boogeymen, or those dull dumb rocks hauled back from the Moon and thrown in my face like coal in a Christmas stocking. It was Bob Solomon, who said he’d come back, stay in touch, continue to shine down his blue-white healing light, because he loved the Earth people, because he loved me, and who done none of them things.” Now Buck is nearing death but still feeling the hurt of having his friend prove faithless. That’s the first story in “Close Encounters,” and contrary to what you might expect, it is not a piece of critical invention on my part. It was Andy Duncan himself who cut it out of the text and read it at a convention without the least suggestion that there was more. Imagine my surprise, then, to discover that the story goes on. After his dark apotheosis, at the urging of the importunate stringer, Buck proceeds to drop in on some UFO researchers investigating mysterious recurrent lights, sees the lights, makes a fool of himself, and is thoroughly humiliated to boot. Yet in the process, he proves himself faithful to the dream. Subsequently he puts together bits and pieces of clues that the stringer dropped for him to realize that she is actually Captain Aura Rhanes, a Space Sister from the planet Clarion, come to test and redeem him. Having proved his worth, it is strongly implied, he will have returned to him all that he has lost: his youth, his health, his innocence, the universe of Gernsbackian scientifiction and old school ufology, the love and friendship of Bob Solomon and the other Space Brothers, and even his beloved giant dog. This is an excellent story and I’m sure the vast majority of its readers enjoyed it immensely. But, as Buck might put it, it’s not a patch on the first story. Which is a moving meditation on old age, death, loss, and how even positive changes can look like a catastrophe to a man who’s in no position to benefit from them. The second half of “Close Encounters” is good enough that I would not want to see it stripped away. But, reader, pause at the midway point to admire just how powerful the first story is.

And as long as you're thinking about Andy Duncan . . .

Andy's classic story "Beluthahatchie" has been reprinted on the Clarkesworld site. You can read it here. He also posted an essay about writing that story over on his blog. You can read that here.

One thing Andy doesn't mention is that at the Clarion West in question, I went over his story with him and (because that was my job) gave him a laundry list of changes to make. So far as I can tell, he made not a single one.

You have to admire that in a writer.

My review of "Close Encounters" is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick; it first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction. The image above is of Andy Duncan's first collection. It's a terrific book. You should buy it.

*

Did you know? A run of the mill paperback science fiction or fantasy novel will typically get more and longer reviews than a story that wins both the Hugo and Nebula awards. That's why when I can find the time -- and more and more, I have so much on my plate that I can't find the time, alas -- I write reviews of particularly splendid exemplars of short fiction and publish them in the New York Review of Science Fiction.

A little over a month ago, I reviewed three works of fiction and an essay there, and it occurred to me to share them, one at a time, over the next few weeks. Here's the first:

Andy Duncan, of whose work one can predict nothing save that it will be beautifully written, has produced what is, even for him, a genuine oddity in “Close Encounters,” a story which originally appeared in his 2012 collection, The Pottawattomie Giant and Other Stories (PS Publishing), was subsequently reprinted in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and two separate best of the year anthologies, and went on to win the Nebula Award for Best Novelette. It is at one and the same time two distinct stories, one of them very good indeed and the other much better than that. “Close Encounters” is narrated by Buck Nelson, a crusty Ozarks farmer in his eightieth-odd year. In his youth he wrote a book about his adventures with a space alien named Bob Solomon, who took him to the Moon, Mars, and Venus, and gave him a giant dog named Bo. For years after that, Buck threw an annual for-profit picnic on his farm for UFO enthusiasts. But now he is a bitter old man, dodging the dwindling number of reporters who occasionally seek him out, and mulling over the disappointments of his life. As always when Duncan is playing with Southern rhythms, the prose sparkles. Here’s Buck’s reply, when asked by a stringer for the Associated Press why he stopped the picnics and started running visitors off with a shotgun:

“You can see your own self what happened,” I said. “Woman, I got old. You’ll see what it’s like, when you get there. All the people who believed in me died, and then the ones who humored me died, and now even the ones who feel obliged to sort of tolerate me are starting to go. Bo died, and Teddy, that was my Earth-born dog, he died, and them government boys went to the Moon and said they didn’t see no mining operations or colony domes or big Space Brother dogs, or nothing else old Buck had seen up there. And in place of my story, what story did they come up with? I ask you. Dust and rocks and craters as far as you can see, and when you walk as far as that there’s another sight of dust and rocks and craters, and so on all around till you’re back where you started, and that’s it, boys, wash your hands, that’s the moon done. Excepting for some spots where the dust is so deep a body trying to land would just be swallowed up, sink to the bottom, and at the bottom find what? Praise Jesus, more dust, just what we needed. They didn’t see nothing that anybody would care about going to see. No floating cars, no lakes of diamonds, no topless Moon gals, just dumb dull nothing. Hell, they might as well a been in Arkansas. You at least can cast a line there, catch you a bream. Besides, my lumbago come back,” I said, easing myself down into the rocker, because we was back on my front porch by then. “It always comes back, my doctor says. Doctors plural, I should say. I’m on the third one now. The first two died on me. That’s something, ain’t it? For a man to outlive two of his own doctors?”

Prose that good is its own justification, and Buck presents a strong argument for the superiority of Romance, however tawdry, over mere reality. But straight talker though he seems to be, the old man is hiding something. For most of the first half of “Close Encounters,” the question of whether Buck lied about the Space Brothers in order to get attention and make a little money on the side is left open. But then at mid-point, he opens up to the reader about “. . . the real reason I give up on the picnics, turned sour on the whole flying-saucer industry, and kept close to the willows ever since. It warn’t my damn lumbago or the Mothman or Barney and Betty Hill and their Romper Room boogeymen, or those dull dumb rocks hauled back from the Moon and thrown in my face like coal in a Christmas stocking. It was Bob Solomon, who said he’d come back, stay in touch, continue to shine down his blue-white healing light, because he loved the Earth people, because he loved me, and who done none of them things.” Now Buck is nearing death but still feeling the hurt of having his friend prove faithless. That’s the first story in “Close Encounters,” and contrary to what you might expect, it is not a piece of critical invention on my part. It was Andy Duncan himself who cut it out of the text and read it at a convention without the least suggestion that there was more. Imagine my surprise, then, to discover that the story goes on. After his dark apotheosis, at the urging of the importunate stringer, Buck proceeds to drop in on some UFO researchers investigating mysterious recurrent lights, sees the lights, makes a fool of himself, and is thoroughly humiliated to boot. Yet in the process, he proves himself faithful to the dream. Subsequently he puts together bits and pieces of clues that the stringer dropped for him to realize that she is actually Captain Aura Rhanes, a Space Sister from the planet Clarion, come to test and redeem him. Having proved his worth, it is strongly implied, he will have returned to him all that he has lost: his youth, his health, his innocence, the universe of Gernsbackian scientifiction and old school ufology, the love and friendship of Bob Solomon and the other Space Brothers, and even his beloved giant dog. This is an excellent story and I’m sure the vast majority of its readers enjoyed it immensely. But, as Buck might put it, it’s not a patch on the first story. Which is a moving meditation on old age, death, loss, and how even positive changes can look like a catastrophe to a man who’s in no position to benefit from them. The second half of “Close Encounters” is good enough that I would not want to see it stripped away. But, reader, pause at the midway point to admire just how powerful the first story is.

And as long as you're thinking about Andy Duncan . . .

Andy's classic story "Beluthahatchie" has been reprinted on the Clarkesworld site. You can read it here. He also posted an essay about writing that story over on his blog. You can read that here.

One thing Andy doesn't mention is that at the Clarion West in question, I went over his story with him and (because that was my job) gave him a laundry list of changes to make. So far as I can tell, he made not a single one.

You have to admire that in a writer.

My review of "Close Encounters" is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick; it first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction. The image above is of Andy Duncan's first collection. It's a terrific book. You should buy it.

*

Published on May 05, 2014 07:43

The Two Faces of Andy Duncan's Encounters!

.

Did you know? A run of the mill paperback science fiction or fantasy novel will typically get more and longer reviews than a story that wins both the Hugo and Nebula awards. That's why when I can find the time -- and more and more, I have so much on my plate that I can't find the time, alas -- I write reviews of particularly splendid exemplars of short fiction and publish them in the New York Review of Science Fiction.

A little over a month ago, I reviewed three works of fiction and an essay there, and it occurred to me to share them, one at a time, over the next few weeks. Here's the first:

Andy Duncan, of whose work one can predict nothing save that it will be beautifully written, has produced what is, even for him, a genuine oddity in “Close Encounters,” a story which originally appeared in his 2012 collection, The Pottawattomie Giant and Other Stories (PS Publishing), was subsequently reprinted in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and two separate best of the year anthologies, and went on to win the Nebula Award for Best Novelette. It is at one and the same time two distinct stories, one of them very good indeed and the other much better than that. “Close Encounters” is narrated by Buck Nelson, a crusty Ozarks farmer in his eightieth-odd year. In his youth he wrote a book about his adventures with a space alien named Bob Solomon, who took him to the Moon, Mars, and Venus, and gave him a giant dog named Bo. For years after that, Buck threw an annual for-profit picnic on his farm for UFO enthusiasts. But now he is a bitter old man, dodging the dwindling number of reporters who occasionally seek him out, and mulling over the disappointments of his life. As always when Duncan is playing with Southern rhythms, the prose sparkles. Here’s Buck’s reply, when asked by a stringer for the Associated Press why he stopped the picnics and started running visitors off with a shotgun:

Prose that good is its own justification, and Buck presents a strong argument for the superiority of Romance, however tawdry, over mere reality. But straight talker though he seems to be, the old man is hiding something. For most of the first half of “Close Encounters,” the question of whether Buck lied about the Space Brothers in order to get attention and make a little money on the side is left open. But then at mid-point, he opens up to the reader about “. . . the real reason I give up on the picnics, turned sour on the whole flying-saucer industry, and kept close to the willows ever since. It warn’t my damn lumbago or the Mothman or Barney and Betty Hill and their Romper Room boogeymen, or those dull dumb rocks hauled back from the Moon and thrown in my face like coal in a Christmas stocking. It was Bob Solomon, who said he’d come back, stay in touch, continue to shine down his blue-white healing light, because he loved the Earth people, because he loved me, and who done none of them things.” Now Buck is nearing death but still feeling the hurt of having his friend prove faithless. That’s the first story in “Close Encounters,” and contrary to what you might expect, it is not a piece of critical invention on my part. It was Andy Duncan himself who cut it out of the text and read it at a convention without the least suggestion that there was more. Imagine my surprise, then, to discover that the story goes on. After his dark apotheosis, at the urging of the importunate stringer, Buck proceeds to drop in on some UFO researchers investigating mysterious recurrent lights, sees the lights, makes a fool of himself, and is thoroughly humiliated to boot. Yet in the process, he proves himself faithful to the dream. Subsequently he puts together bits and pieces of clues that the stringer dropped for him to realize that she is actually Captain Aura Rhanes, a Space Sister from the planet Clarion, come to test and redeem him. Having proved his worth, it is strongly implied, he will have returned to him all that he has lost: his youth, his health, his innocence, the universe of Gernsbackian scientifiction and old school ufology, the love and friendship of Bob Solomon and the other Space Brothers, and even his beloved giant dog. This is an excellent story and I’m sure the vast majority of its readers enjoyed it immensely. But, as Buck might put it, it’s not a patch on the first story. Which is a moving meditation on old age, death, loss, and how even positive changes can look like a catastrophe to a man who’s in no position to benefit from them. The second half of “Close Encounters” is good enough that I would not want to see it stripped away. But, reader, pause at the midway point to admire just how powerful the first story is.

And as long as you're thinking about Andy Duncan . . .

Andy's classic story "Beluthahatchie" has been reprinted on the Clarkesworld site. You can read it here. He also posted an essay about writing that story over on his blog. You can read that here.

One thing Andy doesn't mention is that at the Clarion West in question, I went over his story with him and (because that was my job) gave him a laundry list of changes to make. So far as I can tell, he made not a single one.

You have to admire that in a writer.

My review of "Close Encounters" is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick; it first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction. The image above is of Andy Duncan's first collection. It's a terrific book. You should buy it.

*

Did you know? A run of the mill paperback science fiction or fantasy novel will typically get more and longer reviews than a story that wins both the Hugo and Nebula awards. That's why when I can find the time -- and more and more, I have so much on my plate that I can't find the time, alas -- I write reviews of particularly splendid exemplars of short fiction and publish them in the New York Review of Science Fiction.

A little over a month ago, I reviewed three works of fiction and an essay there, and it occurred to me to share them, one at a time, over the next few weeks. Here's the first:

Andy Duncan, of whose work one can predict nothing save that it will be beautifully written, has produced what is, even for him, a genuine oddity in “Close Encounters,” a story which originally appeared in his 2012 collection, The Pottawattomie Giant and Other Stories (PS Publishing), was subsequently reprinted in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and two separate best of the year anthologies, and went on to win the Nebula Award for Best Novelette. It is at one and the same time two distinct stories, one of them very good indeed and the other much better than that. “Close Encounters” is narrated by Buck Nelson, a crusty Ozarks farmer in his eightieth-odd year. In his youth he wrote a book about his adventures with a space alien named Bob Solomon, who took him to the Moon, Mars, and Venus, and gave him a giant dog named Bo. For years after that, Buck threw an annual for-profit picnic on his farm for UFO enthusiasts. But now he is a bitter old man, dodging the dwindling number of reporters who occasionally seek him out, and mulling over the disappointments of his life. As always when Duncan is playing with Southern rhythms, the prose sparkles. Here’s Buck’s reply, when asked by a stringer for the Associated Press why he stopped the picnics and started running visitors off with a shotgun:

“You can see your own self what happened,” I said. “Woman, I got old. You’ll see what it’s like, when you get there. All the people who believed in me died, and then the ones who humored me died, and now even the ones who feel obliged to sort of tolerate me are starting to go. Bo died, and Teddy, that was my Earth-born dog, he died, and them government boys went to the Moon and said they didn’t see no mining operations or colony domes or big Space Brother dogs, or nothing else old Buck had seen up there. And in place of my story, what story did they come up with? I ask you. Dust and rocks and craters as far as you can see, and when you walk as far as that there’s another sight of dust and rocks and craters, and so on all around till you’re back where you started, and that’s it, boys, wash your hands, that’s the moon done. Excepting for some spots where the dust is so deep a body trying to land would just be swallowed up, sink to the bottom, and at the bottom find what? Praise Jesus, more dust, just what we needed. They didn’t see nothing that anybody would care about going to see. No floating cars, no lakes of diamonds, no topless Moon gals, just dumb dull nothing. Hell, they might as well a been in Arkansas. You at least can cast a line there, catch you a bream. Besides, my lumbago come back,” I said, easing myself down into the rocker, because we was back on my front porch by then. “It always comes back, my doctor says. Doctors plural, I should say. I’m on the third one now. The first two died on me. That’s something, ain’t it? For a man to outlive two of his own doctors?”

Prose that good is its own justification, and Buck presents a strong argument for the superiority of Romance, however tawdry, over mere reality. But straight talker though he seems to be, the old man is hiding something. For most of the first half of “Close Encounters,” the question of whether Buck lied about the Space Brothers in order to get attention and make a little money on the side is left open. But then at mid-point, he opens up to the reader about “. . . the real reason I give up on the picnics, turned sour on the whole flying-saucer industry, and kept close to the willows ever since. It warn’t my damn lumbago or the Mothman or Barney and Betty Hill and their Romper Room boogeymen, or those dull dumb rocks hauled back from the Moon and thrown in my face like coal in a Christmas stocking. It was Bob Solomon, who said he’d come back, stay in touch, continue to shine down his blue-white healing light, because he loved the Earth people, because he loved me, and who done none of them things.” Now Buck is nearing death but still feeling the hurt of having his friend prove faithless. That’s the first story in “Close Encounters,” and contrary to what you might expect, it is not a piece of critical invention on my part. It was Andy Duncan himself who cut it out of the text and read it at a convention without the least suggestion that there was more. Imagine my surprise, then, to discover that the story goes on. After his dark apotheosis, at the urging of the importunate stringer, Buck proceeds to drop in on some UFO researchers investigating mysterious recurrent lights, sees the lights, makes a fool of himself, and is thoroughly humiliated to boot. Yet in the process, he proves himself faithful to the dream. Subsequently he puts together bits and pieces of clues that the stringer dropped for him to realize that she is actually Captain Aura Rhanes, a Space Sister from the planet Clarion, come to test and redeem him. Having proved his worth, it is strongly implied, he will have returned to him all that he has lost: his youth, his health, his innocence, the universe of Gernsbackian scientifiction and old school ufology, the love and friendship of Bob Solomon and the other Space Brothers, and even his beloved giant dog. This is an excellent story and I’m sure the vast majority of its readers enjoyed it immensely. But, as Buck might put it, it’s not a patch on the first story. Which is a moving meditation on old age, death, loss, and how even positive changes can look like a catastrophe to a man who’s in no position to benefit from them. The second half of “Close Encounters” is good enough that I would not want to see it stripped away. But, reader, pause at the midway point to admire just how powerful the first story is.

And as long as you're thinking about Andy Duncan . . .

Andy's classic story "Beluthahatchie" has been reprinted on the Clarkesworld site. You can read it here. He also posted an essay about writing that story over on his blog. You can read that here.

One thing Andy doesn't mention is that at the Clarion West in question, I went over his story with him and (because that was my job) gave him a laundry list of changes to make. So far as I can tell, he made not a single one.

You have to admire that in a writer.

My review of "Close Encounters" is copyright 2014 by Michael Swanwick; it first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction. The image above is of Andy Duncan's first collection. It's a terrific book. You should buy it.

*

Published on May 05, 2014 07:43

Michael Swanwick's Blog

- Michael Swanwick's profile

- 546 followers

Michael Swanwick isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.