Peter Alexander's Blog

March 11, 2016

The Girl Who Threw Stars

Duke heard two more slugs hit his car and swore as he peeked under the chassis to see where the bumpkins were. He didn't see Kong or the younger woman with the knife. He saw instead the hefty legs and feet of what must have been Kong's older female companion. In a shooting stance with a shotgun in her two hands. The woman fired, hitting one of the Bimmer's front tires.

Enraged, Duke fired back from behind the other tire. Took advantage of the rapid-fire the KPB offered. Five shots in a period of a few seconds. A strangled cry came from the heavy woman and she collapsed and rolled over onto the pavement, her shins shot out from under her. Duke watched the woman who had prepared his lunch just moments earlier start dragging the heavy woman back by the wrists. Trying to pull her to safety behind the front facade. A lot of screaming. Duke leapt to his feet and leaned over the fender of his car. Emptied the clip in his first gun on the cook. Both women lay in an inert heap in the breezeway.

Enraged, Duke fired back from behind the other tire. Took advantage of the rapid-fire the KPB offered. Five shots in a period of a few seconds. A strangled cry came from the heavy woman and she collapsed and rolled over onto the pavement, her shins shot out from under her. Duke watched the woman who had prepared his lunch just moments earlier start dragging the heavy woman back by the wrists. Trying to pull her to safety behind the front facade. A lot of screaming. Duke leapt to his feet and leaned over the fender of his car. Emptied the clip in his first gun on the cook. Both women lay in an inert heap in the breezeway.

Published on March 11, 2016 08:52

February 5, 2016

January 29, 2016

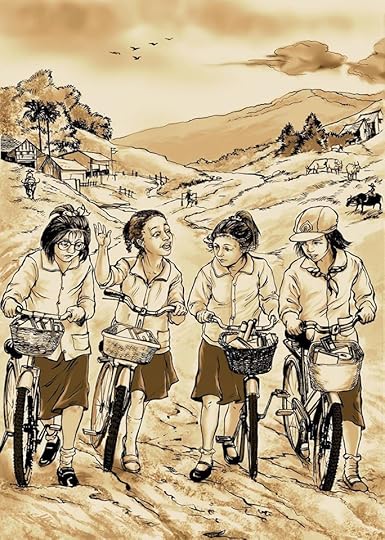

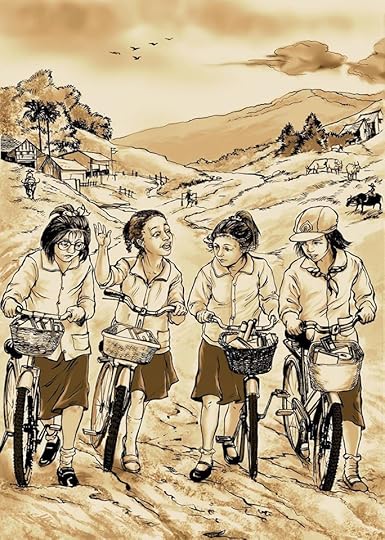

The Girl Who Threw Stars

In my dream the rain never came anymore. The rivers shrank and all the land turned brown. After it was brown, it became white. Like sand. We took whatever belongings we could carry and we started to walk. We would die if we didn't find some place with fruit and water.

Was I there? asked Rai.

You were all there. Pookie had to carry her baby brother. We were all so tired and dying of thirst. Then, when we were just about to give up and lie down and die there in the sand- we saw the ocean.

The ocean? said Pookie. How did we walk so far?

The ocean came to us.

The three girls thought about it, trying to fathom how the sea might find them. The sea was so distant that none of them had ever seen it except on TV and in magazines. Ae smiled knowingly to herself, pausing dramatically.

All the ice and snow in the world had melted, she told them, and the ocean went everywhere. There was nothing left except for desert and ocean.

How could we keep living? asked Pookie.

Ae ran her hand under her hair to remove perspiration. Early in the morning, it was already so hot. She looked off toward the trees beside the road. My dream ended.

Is there any food on a desert? Jam inquired with a worried frown.

Maybe if you can find some snakes or lizards or insects, Ae told her.

What happened to our parents? Ae returned Pookie's question with a fathomless expression that sent the girls a message they didn't want to know

Was I there? asked Rai.

You were all there. Pookie had to carry her baby brother. We were all so tired and dying of thirst. Then, when we were just about to give up and lie down and die there in the sand- we saw the ocean.

The ocean? said Pookie. How did we walk so far?

The ocean came to us.

The three girls thought about it, trying to fathom how the sea might find them. The sea was so distant that none of them had ever seen it except on TV and in magazines. Ae smiled knowingly to herself, pausing dramatically.

All the ice and snow in the world had melted, she told them, and the ocean went everywhere. There was nothing left except for desert and ocean.

How could we keep living? asked Pookie.

Ae ran her hand under her hair to remove perspiration. Early in the morning, it was already so hot. She looked off toward the trees beside the road. My dream ended.

Is there any food on a desert? Jam inquired with a worried frown.

Maybe if you can find some snakes or lizards or insects, Ae told her.

What happened to our parents? Ae returned Pookie's question with a fathomless expression that sent the girls a message they didn't want to know

Published on January 29, 2016 08:30

January 18, 2016

The Girl Who Threw Stars

Young Ae went into the darkest night to find water for the Great Tree. Further upstream she suddenly heard a chopping sound. Trembling, the girl stared into the night where she saw the figure of a woman swinging a machete. Ae screamed shrilly once she realized what the woman was chopping.

Downstream, Kan was bathing peacefully in the river, her first chance to get clean after hiding from Duke. She heard the clamorous screaming of the child in the distance, and quickly got dressed, pulling from her indispensable silver bag everything she might require if an assault was taking place against a child. Across her face she tied a bandana. She still needed not to be recognized.

The Girl Who Threw Stars

Downstream, Kan was bathing peacefully in the river, her first chance to get clean after hiding from Duke. She heard the clamorous screaming of the child in the distance, and quickly got dressed, pulling from her indispensable silver bag everything she might require if an assault was taking place against a child. Across her face she tied a bandana. She still needed not to be recognized.

The Girl Who Threw Stars

Published on January 18, 2016 09:50

December 23, 2015

The Girl Who Threw Stars

Kan Questions Phra Choktawee

Choktawee: What kind of questions did the Christians pay you to answer?

Kan: Two thousand baht for an hour just to talk about Jesus. They said unless we love Jesus – only Jesus – not Lord Buddha, that we will burn in Hell forever. It frightened us, Pra. They said only Jesus could forgive us. Do you think…our religion. . .

Choktawee: Anyone who tells you to fear God is telling you a fallacy. It is like telling water that it is not wet.

Kan: I don’t understand, Pra.

Choktawee: You and I are Buddha, Kan. So are those men who pay you money to receive your comfort. We cannot be put in any Hell that we do not create for ourselves. We are creators, child, beginning with our physical bodies. We may change form, like water, but we are always water.

Reviews:

Mare Thornton :What a beautiful spirit Kanthida is. She touched my soul. "74, wanted and would pay money to have me".

Mintra Pongwasa : I really excited to read a thriller with a true Thai heroine! Thanks!

Choktawee: What kind of questions did the Christians pay you to answer?

Kan: Two thousand baht for an hour just to talk about Jesus. They said unless we love Jesus – only Jesus – not Lord Buddha, that we will burn in Hell forever. It frightened us, Pra. They said only Jesus could forgive us. Do you think…our religion. . .

Choktawee: Anyone who tells you to fear God is telling you a fallacy. It is like telling water that it is not wet.

Kan: I don’t understand, Pra.

Choktawee: You and I are Buddha, Kan. So are those men who pay you money to receive your comfort. We cannot be put in any Hell that we do not create for ourselves. We are creators, child, beginning with our physical bodies. We may change form, like water, but we are always water.

Reviews:

Mare Thornton :What a beautiful spirit Kanthida is. She touched my soul. "74, wanted and would pay money to have me".

Mintra Pongwasa : I really excited to read a thriller with a true Thai heroine! Thanks!

December 9, 2015

Walter Brown

Walter Brown

By Peter Alexander

©2015 Peter Alexander

Installment 001

Walter Brown did not think of himself as unusual or unique. He felt quite normal. He loved two things more than anything: sketching and baseball. By third grade he was taller than most of the other boys in his class. That wasn’t unique, but it did give him a slightly different mien. That and his controlled manner. He didn’t have enemies. Not in those early days. There were just ten other boys and eleven girls. It was a small public school in Rutland, Maine.

He lived with his parents and younger brother, Chris, on a farm on a hill. There they grew vegetables, particularly fine and fat tomatoes, and raised two dozen chickens. From the age of six, Walter regularly worked on the farm. He fed the chickens, collected their eggs in a basket, brought them to his mom, Lucinda, eventually delivered eggs to their neighbors, carried fence posts, helped his father dig holes for the fences, and weeded the garden. Although weeding bored him, he understood the necessity. Walter usually enjoyed those times with his father, whose name was Henry. Henry’s friends most often called him Hank.

Walter talked baseball with his father. It was probably those conversations, in addition to watching the Red Sox on TV that inspired his growing affection for the game. Since they lived in Maine, they never got to see the Red Sox at Fenway, but watching them on TV was sufficient to burgeon that love the father and son shared.

You’ll be a first baseman, Hank told his son. You’re gonna be tall and skinny- sinewy- sort of like Ted Williams, if you’re lucky.

He wasn’t a first baseman, Walter said.

Yeah. But you’re gonna have that sort of build. I see you like sorta a scrappy, quick on your feet first baseman. Cover that bag. Range over toward second and pick off that ball screaming into right field. Hank had played for the Rutland Men’s Team for half a dozen years. After farm work was done, Walters father would hit him grounders in the rough field they had leveled out back of the house. When Walter turned seven, Hank bought him a real first baseman’s mitt.

End of Installment 001

Walter Brown

By Peter Alexander

© 2015 Peter Alexander

Installment 002

For Walter, baseball and school were his daytime occupations; homework and sketching consumed most of his evenings, except occasionally when the Sox were performing on the Tube.

Sketching was an activity Walter pursued more privately. Mom peeked in his upstairs bedroom on occasion, but she knew her son didn’t like to show his work until he was totally sanguine about it. His brother Chris, three years younger, slept in a converted pantry downstairs. He loved video games, which Walter despised, so the two brothers often became virtual strangers.

Walter’s sketches began with the chickens. He liked to watch them. The chickens seemed to like him, particularly since he had become their functional source of food. He started with his school notebook and no. 3 pencils. He sat on an orange canvas chair, one of four, which the family took to Pine Point Beach in the summer, and stared the chickens. If you look closely at things, he began to realize, you can see things you never noticed before.

He quickly discovered that the no. 3 pencils he took to school were unsatisfactory. His sketches, he realized, were too light, providing only a dull, characterless gray. He took what remained of his allowance and rode his bike down to Ferguson’s to buy himself a box of no. 2s.

He wanted to somehow capture the essence of the birds, and found the no. 2s far more serviceable. The softer lead permitted Walter to vary the degrees of blackness he sought to contrast the colors of the chickens’ feathers within the black and white scale. He next began looking for the details of people’s faces- his classmates, his parents and brother at the dinner table. Walter was pleased to note, for instance, the changes in his father’s narrow face when his reactions shifted. Night after night he tried to recapture from memory those faces in his notebook.

When he attempted to sketch his mother’s face, he was challenged by a new problem- a woman’s hair. A woman’s hair and chicken feathers. Intriguing. Walter found the hair of women and girls offered much more variety than men’s hair. His father and brother’s hair seemed much easier. He realized in those early days how miserably he failed in sketching women. Chickens were easier, especially the eyes.

I can’t draw you, mom, he admitted sheepishly to Lucinda. Your hair is tough.

They call me a dirty blonde, she smiled.

Your hair isn’t dirty, mom, he insisted, suddenly feeling embarrassed for them both.

That’s what they call my color, she laughed. It’s not really dirty.

You wash you hair a lot.

Yes, darling, his mother laughed. Dirty blonde just means dark blonde, she explained. It’s not dark enough to be brown.

He shook his head. I don’t know how to sketch your hair, mom.

Well, Walter, I think Berwick has an art supply store. We’ll go shopping over there this weekend, and see if they have any books on sketching. Okay?

They found an art supply store with a sketchbook for artists in Berwick. To his joy and amazement, Walter discovered that the store offered a variety of black lead pencils. The book didn’t call the drawing material in the pencil lead. It called it graphite, and there many different types. Pencils that had an ‘H’ grade had harder graphite and ‘B’ pencils were softer. When Walter made a mark with the ‘B’ pencils, the mark was darker. Darker than the normal no. 2 he had been using. These professional pencils were far more expensive than the common pencils the kids used in school.

It’s an expensive bobby, his mother noted.

Not as expensive as baseball.

Right. You broke the bat your father bought you. How long did that last? Two days?

I hit it inside. I taped it up. I still use it. It’s okay.

Lucinda nibbled on a fingernail. She looked into Walter’s eyes. I’ll buy you two pencils, she said finally. I want to see your Math grades get better.

They will, mom. Promise. You don’t have to get me two pencils.

I think you need two, she said, if you want to draw dirty blond hair.

End of Installment 002

Installment 003

Blair Shepard grounded a slow roller toward shortstop. Blair barreled down the first base line. He was a hefty 7th grader, not very speedy. But building momentum. He saw the lanky first baseman, Walter Brown, a 5th grader, stretching his glove arm, waiting for the throw from Stevie Glynn, the shortstop. Stevie was charging the roller. His throw would have to be almost perfect to catch the lumbering base runner.

Out of the corner of his eye, Blair saw the ball sailing out of Stevie’s hand. Heard his own feet pounding on the baseline. Saw the bag coming so close. Without even forming the thought, he attempted to run over the smaller, younger boy. As Blair heard the baseball thud into Walter’s mitt, he saw his own cleats about to land on the boy’s ankle, which was beginning to come off the bag. The 7th grader’s meaty shoulder was about to collide with the thinner one, when it peeled away. Blair’s body touched the sleeve of Walter’s T-shirt, and then the first baseman was away, tossing the ball around the infield as infielders usually did after an out was recorded. The boy had been untouchable.

Angrily, Blair stomped back along the right field, bellowing, Safe! I was safe!

As he directed his angry claim to Jeff Townsend, the pitcher, and alpha leader of the group assembled after school to play ball, Walter ignored him, sharing a smile with the second baseman, which Blair could not see.

You were out, asshole! On the mound Jeff gave him a look reserved for assholes, which everybody could recognize. Sit down, you fat pussy! They stared daggers at one another for a few seconds, and then, muttering and shaking his head, Blair joined his teammates on the sidelines. Jeff was his classmate, not particularly a friend, but had Blair been playing on his team, he probably would have called him safe.

Walter had that smooth way about him. Even as a younger child, he managed to avoid unnecessary smashups. He was a calm child. Unemotional? Not necessarily. He simply possessed a high degree of self-control. Walter would not know to call himself self-controlled. It just came naturally to him. Also, he had inherited a good deal of his personality from Lucinda, his mother.

In those days, boys just gathered on their own to form teams after school and compete in baseball games, without adults, coaches, or umpires. Today, Jeff’s team with the 5th grader on first, won 9 to 5. Walter had ripped a double to right center, driving in a pair of runs, again surprising the older boys with his power. Hank had told his son how Ted Williams practiced strengthening his wrists by holding a bat in one hand at a time, rolling his wrists until they gradually built up strength. Power hitting was primarily in the wrists. Walter practiced a half hour almost every night in front of his mirror. Sometimes he slept with the bat in his bed because he had heard some pros did that. The bat was their best friend.

After the game as he walked his bicycle up the hill toward home with classmates Bobby Shaw and Curt Carlino, their conversation drifted back to observations formed during the school day in their classroom.

Miss Topham’s tits aren’t even, Curt ventured. Did ya notice?

Huh? Walter responded. His mind had been replaying the double.

Bobby started laughing. Yeah, maybe Mister Alisch been sucking on one uh them too much.

Walter was momentarily silent. Miss Topham was their homeroom teacher. She taught English and Geography, courses that represented Walter’s best grades, and he liked her. Miss Topham was blonde-haired looked to be no more than thirty years old, and was rather pretty in a serious way.

Today she had worn a blue blouse with white dots. Granted, it had been tight, too. Her breasts looked quite pointy; the image returned to Walter’s memory. He had tried not to think too much about them, but he was interested. Somehow, he felt in an unspoken way, that it was not respectful, nor kind, to discuss Miss Topham’s breasts with his friends. And now this issue of the symmetry of his teacher’s breasts presented a new factor. They had speculated that Mr. Alisch – their gym teacher – was possibly Miss Topham’s boyfriend. But the only real evidence anyone had was that they had been seen together once or twice in his green Chrysler. Walter had no idea where each of them lived. Maybe Mr. Alisch was giving Miss Topham a ride home. They didn’t act suspicious in school, no holding hands, or touching-- and kids like Curt kept an eye on those things. They ate lunch together occasionally in the cafeteria, but Walter thought it only had happened when another teacher was present.

He liked Mr. Alisch, too. With his cool Charles Bronson moustache, wavy dark hair and sporty jackets. Every so often after school, he would drive Walter and some of the other boys to neighboring towns to compete in various sports competitions. The school didn’t make him do that. Mr. Alisch just seemed to enjoy coaching the kids.

I saw Nikki Barbarosa’ s tits, too, Curt announced.

She doesn’t have tits, Bobby asserted.

Hey, I sit behind her, don’t I? Sometimes she wears those shirts without sleeves.

Walter listened with vexatious curiosity. He wasn’t comfortable with the direction their chatter was taking, but he needed to know more things. He didn’t want to be out of it.

They’re little nubby tits, Curt was explaining. Then they got these nice pink whattayoucallits – nipples. They’re really neat. Gave me a boner, man!

I thought girls were starting to wear bras, Walter interjected.

Not all of ‘em, Bobby said.

My sister said she hated wearing bras, Curt said. My mom made her.

Bobby: Didja see her tits?

Curt: My sister’s?

Bobby: Yeah.

Curt: She’s kill me if she caught me looking.

Bobby: Yeah, so? Didya look?

Curt: Well, accidentally.

They laughed. Walter smiled.

Curt: Through the crack in her bedroom door.

Bobby laughed excitedly. Did you see her crack, too?

Walter: Did you guys see Blair try to run me over at first base today?

End of Installment 003

004

When Walter got home, the place was empty except for their two cats. It was almost 5 o’clock. Maybe his father was still working at Uncle Howie’s lumberyard, but mom typically would be starting to prepare dinner, and Chris would be watching The Flintstones on TV. But, there was nobody. No car. They owned one car, a blue 1972 Ford station wagon, which Hank used primarily.

The house was silent. He was slightly relieved to see Red and Sox sleeping on the couch. Their cats were proof, he thought, that he hadn’t stepped into The Twilight Zone. They rolled over when they saw him, stretched and flopped into new positions before falling back asleep.

He went to the refrigerator and got a fudge sickle from the freezer. If mom wasn’t making dinner, Walter wouldn’t be spoiling his appetite. Anyway, the baseball game had made him hungry. Where were they? He walked out back and checked the chickens and cast his eyes over the garden.

Hey, Uncle Howie. It’s me. Walt. Is my dad there?

No, Walt. On the telephone Uncle Howie’s voice sounded odd. They’re at the hospital. They’re all at the hospital. Chrissie got hurt.

Huh? Chris got hurt? What happened?

He fell out of a tree, Walter, Broke his arm. Maybe something else. I don’t know. Are you at the house?

Yeah. Is Chris gonna be all right?

I think so. Yeah. Don’t worry. Your dad didn’t know where you was, so nobody—they had to take him to the hospital. I’ll call them. At the hospital. Tellem you’re home. Don’t worry. Your dad’ll come home and get you. Don’t worry, Walter.

After he hung up the phone, he stood in the kitchen, feeling dazed. Chris had fallen out of a tree. Chris didn’t climb trees Walter did. Why?

He didn’t think about his brother too often. They had different friends, different interests. He pictured his brother in his mind. A series of flashes. Different pictures. The day they brought him home from the hospital- a baby. His chubby cheeks becoming apple red when he laughed, how easily he cried, how his father scared him, the terror in his eyes, his softness. This was his brother whom he was seldom kind to. Not actually unkind, just indifferent. Now in the hospital again. Having fallen out of a tree. He could have hit his head. He could be dead. But he was still here. He would be home again.

Walter took the bag of Friskies from the cupboard into the living room and sat down with the cats. They awoke when they smelled the bag, their noses probing him. The phone rang.

Walter- you okay, kid? His father’s voice.

Yes, dad.

We’re at the hospital.

I know. How’s Chris?

They’re putting a cast on his arm. You know, like I had that time.

Yeah, your accident.

Crazy kid, climbing that tree with those two girls. He just wanted to get higher than them.

Who?

Nelly and Viv. His father laughed, and then coughed his cigarette cough into the phone. Get in trouble playing with those two. They prob’ly lured him up there. Chris don’t usually climb trees.

I know. I was surprised.

His father chuckled. Mom an me will be home soon. Chris is gonna stay here overnight. What kinda food you want to eat tonight, Walter? We’ll pick something up.

The cats had toppled the bag of Friskies. They were smart. They had scattered the fish pellets all over the couch, some down between the cushions. Sox, the white one was fishing for them with her paw. Red, the older, fatter reddish brown angora, was satisfied finding enough food on the cushion surfaces. For Sox, it had become more like a game, finding those pellets hiding from her. Walter overturned the cushions, scattering the cats, and began scooping up the loose pellets. He found loose change, too, under the cushions- 32 cents worth. He looked at the coins in his palm, giving them some thought, but then he walked into the kitchen and laid them on the counter.

Walter thought about how his brother would manage at age seven with a broken arm and cast. Kids in the second grade would pay more attention to him. They’d write their names and maybe some silly things on his cast. Mom would have to wash him up more often. People would want to help him do things. Maybe Chris would enjoy it. Some of the time. He remembered when his own classmate, Robin LaClerque, had broken his wrist skateboarding. He had a cast. He also had screws in his bone. After a while the novelty wore off and it became a major pain in his ass. Walter hoped nothing like that would happen to him. He thought of a word he had heard. Freewheeling. He thought he understood what it meant. That’s what he wanted to be – freewheeling.

End: 004

005:

The ride from Walter’s home to the school in the morning took the bikers up and down several hills. They had enough time to walk their bikes up the steepest of the hills. Anyway, though the boys- Walter and Tony Hoagland- were strong enough to ride up the hill, they were joined this morning by Sally Herman, another neighbor, and being a girl, she stopped in mid-conversation and started walking her bike. The boys, out of courtesy, stepped off their bikes, and hiked up the hill, arranged as a pair on her left.

Sally was a year older, in the sixth grade. All three lived within a half-mile of one another. Sally’s parents owned two horses, which they kept in a barn. On occasion, Walter got to ride Pepper, the horse with the gray coat and black spots.

Burleson had to rush his throw, Tony was saying.

He came up with the ball too fast. Kuiper’s pretty fast, Walter observed.

Winning run on third. It always happens when you walk the leadoff guy in the ninth.

Are you mad at Nelly? Sally broke in, directing her question at Walter. Nelly was the third grader who took part in the tree climbing incident that resulted in Chris’ broken arm. Nelly was Sally’s younger sister.

Walter kept his eyes on the street as he pushed his bike. A car passed them. Mr. Croce beeped his horn and waved as he passed them. He was the local barber, and had the same last name as Jim Croce, the popular folk singer who had died two years earlier in a plane crash in Louisiana.

Huh, Walter?

I don’t know. I didn’t think about it, he grunted.

Did she do something? Tony asked. He really didn’t know much about the story; just that Chris had fallen out of the tree and broken his arm.

They were just climbing the tree and Chris fell. Sally made it sound rather normal.

Her and Viv were teasin him. Now Walter sounded nettled.

They didn’t think he was gonna fall. Jeeze. They didn’t push him or anything.

They said he was a baby. Now Walter turned his face toward Sally, but the three continued to push their bikes up the hill.

So, that made him fall? Just because they called him a baby?

Tony kept his mouth shut. This spat was getting interesting.

I don’t know, Sally. Chris is a little kid. Maybe he don’t know how to handle two bratty girls.

Sally stopped walking. She stared at Walter, narrowing her eyes. Two bratty girls? Are you gonna blame Nelly and Vivienne because your brother climbed a tree, and nobody made him, y’ know, an then he fell by himself. She held onto her handle grips tightly and squared her shoulders as she awaited his retort. Walter sort of liked her looks, her reddish hair and everything, but he knew from experience that she liked to argue, that she sometimes enjoyed creating dissension, often when there was no need for it. In his opinion.

We’re gonna be late for school, he said, and pushed his bike even more vigorously up the hill. Tony hurried after him, and Sally was forced to follow them.

Walter’s mind wandered. This was Mr. O’Connell’s room where math was taught, not one of Walter’s favorite periods. White-haired Mr. O’Connell was unpredictable, sometimes very serious about math, occasionally warm and humorous, but often, if his mood changed, he could become sarcastic and cantankerous. Some of his classmates reckoned his mood changes had something to do with his age or, they suggested, a lack of sex.

Four of Walter’s classmates were working on algebra problems on the blackboard. Mr. O’Connell stood behind them, watching silently. He often wore a dark blue suit with thin white stripes, and sometimes collected chalk dust, which angered him. Suddenly he saw how frowzy he appeared, not the dignified professional he sought to portray to the school. Walter had already done his stint at the blackboard, and had survived with minimal deprecation from his teacher, and now could settle down at his desk, his mind wandering back to the sharp words between Sally and himself, and to the vague sense that somehow he had been partially responsible for his younger brother’s misery.

Sally giving him a hard time. Like blaming Chris and defending those bratty girls. What was her problem? He hadn’t said anything about her sister to Sally. Not initially, anyway. Not until she started asking him if he was mad at Nelly. Nelly was not on his mind until then. He had been talking about the ninth inning defeat suffered by the Red Sox.

He had only told his parents about some of the mischief Nelly and Viv were guilty of, like breaking Old Man Leggett’s window, stuff like that. Chris had been with the girls part of the time, and had been sternly questioned about the window just because someone had seen him aimlessly breaking bottles with rocks on another occasion. Chris should just stay away from those girls, Walter had told his mother and father. They just like to get him in trouble. Had his parents reported his story to Sally and Nelly’s parents?

Sitting there in math class he reflected more deeply about Sally. She had sort of a seventh grade boyfriend, Duane, whom Walter generally disliked. Duane messed with several other girls, too- flirted- he guessed might be the correct word. That was a word her heard in movies a lot, but not often at his school. Sally’s older brother, Nick, had been friendly though, even teaching Walter the rudiments of horseback riding. Now, with Chris’ broken arm, the whole picture seemed to be changing. Walter wondered if he would be invited to the Herman farm anytime soon. Would there be any horseback riding in his future?

End of 005

006:

Sleep was impossible. Walter hated when they fought downstairs in the kitchen. Their strident words easily reached him upstairs. His father with his harshness; his mom with her shrill howling. Walter gave a thought to how much Chris must be suffering, probably sobbing quietly in his small bedroom next to the kitchen. His arm must be aching worse than usual. But his brother wouldn’t dare cry for help, especially when their arguing was largely connected to him.

- First you let him climb a tree unsupervised! Then—

- My God, Hank! I was making beds! And—

- Yeah, yeah, yeah—I heard that fifty times—

- Because that’s the fact!

- I know what you do at eleven o’clock—you’re watching the fuckin soap opera!

- You’re a nasty bastard, Hank!

- And today you leave Chrissie alone with Mrs. Crossley!

- So I could earn a little money for my family! Her voice rose with indignation. Walter imagined that now tears were starting to fall from his mother’s eyes. – And stop the vile language! The boys can hear you all over the house. You’re complaining about money all the time. MONEY, Walter thought. It always comes down to that. – so I try to help. Roberta called. Penny likes me to do her hair. She requested me!

- Yeah, while Chris needs you, Lucinda. More than Penny Robertson, for chrissakes!

As Walter’s mother’s wail rose another decibel, his father’s roar surpassed it. - And Mrs. Crossley is getting into my Jack Daniels!

- You can’t prove that, Hank! Why’re you so cruel!

- Who else? You? Walter? I know how much was in that bottle! Then his father switched tangents. – It must’ve took Chris at least twenny minutes to climb that high. Twenny minutes! You couldn’t take a look out the window in twenny minutes? They got commercials on those soap operas, don’t they? Sure they do! You couldn’t get off your ass?

Then, Walter could actually hear his mother’s sobs. That was more painful than the shouting. I’m not cruel, Lucinda—I’m responsible, he could hear his father say, but he was no longer shouting. Our little boy could’ve bashed his skull in—

- He can hear you, for God’s sake! It was not a shout, but a loud hiss from his mother, audible all the way upstairs. Walter wrapped his pillow around his head in an attempt to block his ears. The thought flashed through his mind that Chris would try to similarly block out the fighting, but with his cast, it might be impossible. The tears helped silence the fight. He felt his own eyes gathering moisture. Then he heard the back door slam.

He heard the Ford start up out back. His father would take out his anger or hopefully extinguish it outside somewhere. Walter didn’t know where his father would go. In fact, he didn’t want to know where his father was going. That might be too much knowledge at this stage of his life.

Walter knew his mother loved her soap operas. If he watched one with her sometimes when he stayed home from school with a cold, he found them prohibitively boring. Men and women were repeatedly arguing. Maybe that’s where adults learned the habit. But he also believed that his mom was a good mother, at least in comparison with a lot of mothers he met in other homes. She kept the house clean; she often worked in the garden; his clothes were clean and pressed. Sometimes he gathered the laundry off the clotheslines and brought them into the basement where she ironed them. If the housework was under control, she sometimes worked at Roberta’s salon, which earned her some money and seemed to give her pleasure as well.

Admittedly, his father worked even harder and longer, which appeared to give him a kind of grim satisfaction. Some days he started in the garden by 6 a.m., and then went to Uncle Howie’s lumberyard by 11. Frequently, he didn’t get home until 6 p.m. where his family and dinner awaited him. If the food had cooled because he was later than expected, Hank muttered or frowned. Griping was not uncommon. He poured some Jack Daniels into a glass.

Walter made his mind seek out happier moments with the family before he could gradually drift off into sleep.

End of 006

By Peter Alexander

©2015 Peter Alexander

Installment 001

Walter Brown did not think of himself as unusual or unique. He felt quite normal. He loved two things more than anything: sketching and baseball. By third grade he was taller than most of the other boys in his class. That wasn’t unique, but it did give him a slightly different mien. That and his controlled manner. He didn’t have enemies. Not in those early days. There were just ten other boys and eleven girls. It was a small public school in Rutland, Maine.

He lived with his parents and younger brother, Chris, on a farm on a hill. There they grew vegetables, particularly fine and fat tomatoes, and raised two dozen chickens. From the age of six, Walter regularly worked on the farm. He fed the chickens, collected their eggs in a basket, brought them to his mom, Lucinda, eventually delivered eggs to their neighbors, carried fence posts, helped his father dig holes for the fences, and weeded the garden. Although weeding bored him, he understood the necessity. Walter usually enjoyed those times with his father, whose name was Henry. Henry’s friends most often called him Hank.

Walter talked baseball with his father. It was probably those conversations, in addition to watching the Red Sox on TV that inspired his growing affection for the game. Since they lived in Maine, they never got to see the Red Sox at Fenway, but watching them on TV was sufficient to burgeon that love the father and son shared.

You’ll be a first baseman, Hank told his son. You’re gonna be tall and skinny- sinewy- sort of like Ted Williams, if you’re lucky.

He wasn’t a first baseman, Walter said.

Yeah. But you’re gonna have that sort of build. I see you like sorta a scrappy, quick on your feet first baseman. Cover that bag. Range over toward second and pick off that ball screaming into right field. Hank had played for the Rutland Men’s Team for half a dozen years. After farm work was done, Walters father would hit him grounders in the rough field they had leveled out back of the house. When Walter turned seven, Hank bought him a real first baseman’s mitt.

End of Installment 001

Walter Brown

By Peter Alexander

© 2015 Peter Alexander

Installment 002

For Walter, baseball and school were his daytime occupations; homework and sketching consumed most of his evenings, except occasionally when the Sox were performing on the Tube.

Sketching was an activity Walter pursued more privately. Mom peeked in his upstairs bedroom on occasion, but she knew her son didn’t like to show his work until he was totally sanguine about it. His brother Chris, three years younger, slept in a converted pantry downstairs. He loved video games, which Walter despised, so the two brothers often became virtual strangers.

Walter’s sketches began with the chickens. He liked to watch them. The chickens seemed to like him, particularly since he had become their functional source of food. He started with his school notebook and no. 3 pencils. He sat on an orange canvas chair, one of four, which the family took to Pine Point Beach in the summer, and stared the chickens. If you look closely at things, he began to realize, you can see things you never noticed before.

He quickly discovered that the no. 3 pencils he took to school were unsatisfactory. His sketches, he realized, were too light, providing only a dull, characterless gray. He took what remained of his allowance and rode his bike down to Ferguson’s to buy himself a box of no. 2s.

He wanted to somehow capture the essence of the birds, and found the no. 2s far more serviceable. The softer lead permitted Walter to vary the degrees of blackness he sought to contrast the colors of the chickens’ feathers within the black and white scale. He next began looking for the details of people’s faces- his classmates, his parents and brother at the dinner table. Walter was pleased to note, for instance, the changes in his father’s narrow face when his reactions shifted. Night after night he tried to recapture from memory those faces in his notebook.

When he attempted to sketch his mother’s face, he was challenged by a new problem- a woman’s hair. A woman’s hair and chicken feathers. Intriguing. Walter found the hair of women and girls offered much more variety than men’s hair. His father and brother’s hair seemed much easier. He realized in those early days how miserably he failed in sketching women. Chickens were easier, especially the eyes.

I can’t draw you, mom, he admitted sheepishly to Lucinda. Your hair is tough.

They call me a dirty blonde, she smiled.

Your hair isn’t dirty, mom, he insisted, suddenly feeling embarrassed for them both.

That’s what they call my color, she laughed. It’s not really dirty.

You wash you hair a lot.

Yes, darling, his mother laughed. Dirty blonde just means dark blonde, she explained. It’s not dark enough to be brown.

He shook his head. I don’t know how to sketch your hair, mom.

Well, Walter, I think Berwick has an art supply store. We’ll go shopping over there this weekend, and see if they have any books on sketching. Okay?

They found an art supply store with a sketchbook for artists in Berwick. To his joy and amazement, Walter discovered that the store offered a variety of black lead pencils. The book didn’t call the drawing material in the pencil lead. It called it graphite, and there many different types. Pencils that had an ‘H’ grade had harder graphite and ‘B’ pencils were softer. When Walter made a mark with the ‘B’ pencils, the mark was darker. Darker than the normal no. 2 he had been using. These professional pencils were far more expensive than the common pencils the kids used in school.

It’s an expensive bobby, his mother noted.

Not as expensive as baseball.

Right. You broke the bat your father bought you. How long did that last? Two days?

I hit it inside. I taped it up. I still use it. It’s okay.

Lucinda nibbled on a fingernail. She looked into Walter’s eyes. I’ll buy you two pencils, she said finally. I want to see your Math grades get better.

They will, mom. Promise. You don’t have to get me two pencils.

I think you need two, she said, if you want to draw dirty blond hair.

End of Installment 002

Installment 003

Blair Shepard grounded a slow roller toward shortstop. Blair barreled down the first base line. He was a hefty 7th grader, not very speedy. But building momentum. He saw the lanky first baseman, Walter Brown, a 5th grader, stretching his glove arm, waiting for the throw from Stevie Glynn, the shortstop. Stevie was charging the roller. His throw would have to be almost perfect to catch the lumbering base runner.

Out of the corner of his eye, Blair saw the ball sailing out of Stevie’s hand. Heard his own feet pounding on the baseline. Saw the bag coming so close. Without even forming the thought, he attempted to run over the smaller, younger boy. As Blair heard the baseball thud into Walter’s mitt, he saw his own cleats about to land on the boy’s ankle, which was beginning to come off the bag. The 7th grader’s meaty shoulder was about to collide with the thinner one, when it peeled away. Blair’s body touched the sleeve of Walter’s T-shirt, and then the first baseman was away, tossing the ball around the infield as infielders usually did after an out was recorded. The boy had been untouchable.

Angrily, Blair stomped back along the right field, bellowing, Safe! I was safe!

As he directed his angry claim to Jeff Townsend, the pitcher, and alpha leader of the group assembled after school to play ball, Walter ignored him, sharing a smile with the second baseman, which Blair could not see.

You were out, asshole! On the mound Jeff gave him a look reserved for assholes, which everybody could recognize. Sit down, you fat pussy! They stared daggers at one another for a few seconds, and then, muttering and shaking his head, Blair joined his teammates on the sidelines. Jeff was his classmate, not particularly a friend, but had Blair been playing on his team, he probably would have called him safe.

Walter had that smooth way about him. Even as a younger child, he managed to avoid unnecessary smashups. He was a calm child. Unemotional? Not necessarily. He simply possessed a high degree of self-control. Walter would not know to call himself self-controlled. It just came naturally to him. Also, he had inherited a good deal of his personality from Lucinda, his mother.

In those days, boys just gathered on their own to form teams after school and compete in baseball games, without adults, coaches, or umpires. Today, Jeff’s team with the 5th grader on first, won 9 to 5. Walter had ripped a double to right center, driving in a pair of runs, again surprising the older boys with his power. Hank had told his son how Ted Williams practiced strengthening his wrists by holding a bat in one hand at a time, rolling his wrists until they gradually built up strength. Power hitting was primarily in the wrists. Walter practiced a half hour almost every night in front of his mirror. Sometimes he slept with the bat in his bed because he had heard some pros did that. The bat was their best friend.

After the game as he walked his bicycle up the hill toward home with classmates Bobby Shaw and Curt Carlino, their conversation drifted back to observations formed during the school day in their classroom.

Miss Topham’s tits aren’t even, Curt ventured. Did ya notice?

Huh? Walter responded. His mind had been replaying the double.

Bobby started laughing. Yeah, maybe Mister Alisch been sucking on one uh them too much.

Walter was momentarily silent. Miss Topham was their homeroom teacher. She taught English and Geography, courses that represented Walter’s best grades, and he liked her. Miss Topham was blonde-haired looked to be no more than thirty years old, and was rather pretty in a serious way.

Today she had worn a blue blouse with white dots. Granted, it had been tight, too. Her breasts looked quite pointy; the image returned to Walter’s memory. He had tried not to think too much about them, but he was interested. Somehow, he felt in an unspoken way, that it was not respectful, nor kind, to discuss Miss Topham’s breasts with his friends. And now this issue of the symmetry of his teacher’s breasts presented a new factor. They had speculated that Mr. Alisch – their gym teacher – was possibly Miss Topham’s boyfriend. But the only real evidence anyone had was that they had been seen together once or twice in his green Chrysler. Walter had no idea where each of them lived. Maybe Mr. Alisch was giving Miss Topham a ride home. They didn’t act suspicious in school, no holding hands, or touching-- and kids like Curt kept an eye on those things. They ate lunch together occasionally in the cafeteria, but Walter thought it only had happened when another teacher was present.

He liked Mr. Alisch, too. With his cool Charles Bronson moustache, wavy dark hair and sporty jackets. Every so often after school, he would drive Walter and some of the other boys to neighboring towns to compete in various sports competitions. The school didn’t make him do that. Mr. Alisch just seemed to enjoy coaching the kids.

I saw Nikki Barbarosa’ s tits, too, Curt announced.

She doesn’t have tits, Bobby asserted.

Hey, I sit behind her, don’t I? Sometimes she wears those shirts without sleeves.

Walter listened with vexatious curiosity. He wasn’t comfortable with the direction their chatter was taking, but he needed to know more things. He didn’t want to be out of it.

They’re little nubby tits, Curt was explaining. Then they got these nice pink whattayoucallits – nipples. They’re really neat. Gave me a boner, man!

I thought girls were starting to wear bras, Walter interjected.

Not all of ‘em, Bobby said.

My sister said she hated wearing bras, Curt said. My mom made her.

Bobby: Didja see her tits?

Curt: My sister’s?

Bobby: Yeah.

Curt: She’s kill me if she caught me looking.

Bobby: Yeah, so? Didya look?

Curt: Well, accidentally.

They laughed. Walter smiled.

Curt: Through the crack in her bedroom door.

Bobby laughed excitedly. Did you see her crack, too?

Walter: Did you guys see Blair try to run me over at first base today?

End of Installment 003

004

When Walter got home, the place was empty except for their two cats. It was almost 5 o’clock. Maybe his father was still working at Uncle Howie’s lumberyard, but mom typically would be starting to prepare dinner, and Chris would be watching The Flintstones on TV. But, there was nobody. No car. They owned one car, a blue 1972 Ford station wagon, which Hank used primarily.

The house was silent. He was slightly relieved to see Red and Sox sleeping on the couch. Their cats were proof, he thought, that he hadn’t stepped into The Twilight Zone. They rolled over when they saw him, stretched and flopped into new positions before falling back asleep.

He went to the refrigerator and got a fudge sickle from the freezer. If mom wasn’t making dinner, Walter wouldn’t be spoiling his appetite. Anyway, the baseball game had made him hungry. Where were they? He walked out back and checked the chickens and cast his eyes over the garden.

Hey, Uncle Howie. It’s me. Walt. Is my dad there?

No, Walt. On the telephone Uncle Howie’s voice sounded odd. They’re at the hospital. They’re all at the hospital. Chrissie got hurt.

Huh? Chris got hurt? What happened?

He fell out of a tree, Walter, Broke his arm. Maybe something else. I don’t know. Are you at the house?

Yeah. Is Chris gonna be all right?

I think so. Yeah. Don’t worry. Your dad didn’t know where you was, so nobody—they had to take him to the hospital. I’ll call them. At the hospital. Tellem you’re home. Don’t worry. Your dad’ll come home and get you. Don’t worry, Walter.

After he hung up the phone, he stood in the kitchen, feeling dazed. Chris had fallen out of a tree. Chris didn’t climb trees Walter did. Why?

He didn’t think about his brother too often. They had different friends, different interests. He pictured his brother in his mind. A series of flashes. Different pictures. The day they brought him home from the hospital- a baby. His chubby cheeks becoming apple red when he laughed, how easily he cried, how his father scared him, the terror in his eyes, his softness. This was his brother whom he was seldom kind to. Not actually unkind, just indifferent. Now in the hospital again. Having fallen out of a tree. He could have hit his head. He could be dead. But he was still here. He would be home again.

Walter took the bag of Friskies from the cupboard into the living room and sat down with the cats. They awoke when they smelled the bag, their noses probing him. The phone rang.

Walter- you okay, kid? His father’s voice.

Yes, dad.

We’re at the hospital.

I know. How’s Chris?

They’re putting a cast on his arm. You know, like I had that time.

Yeah, your accident.

Crazy kid, climbing that tree with those two girls. He just wanted to get higher than them.

Who?

Nelly and Viv. His father laughed, and then coughed his cigarette cough into the phone. Get in trouble playing with those two. They prob’ly lured him up there. Chris don’t usually climb trees.

I know. I was surprised.

His father chuckled. Mom an me will be home soon. Chris is gonna stay here overnight. What kinda food you want to eat tonight, Walter? We’ll pick something up.

The cats had toppled the bag of Friskies. They were smart. They had scattered the fish pellets all over the couch, some down between the cushions. Sox, the white one was fishing for them with her paw. Red, the older, fatter reddish brown angora, was satisfied finding enough food on the cushion surfaces. For Sox, it had become more like a game, finding those pellets hiding from her. Walter overturned the cushions, scattering the cats, and began scooping up the loose pellets. He found loose change, too, under the cushions- 32 cents worth. He looked at the coins in his palm, giving them some thought, but then he walked into the kitchen and laid them on the counter.

Walter thought about how his brother would manage at age seven with a broken arm and cast. Kids in the second grade would pay more attention to him. They’d write their names and maybe some silly things on his cast. Mom would have to wash him up more often. People would want to help him do things. Maybe Chris would enjoy it. Some of the time. He remembered when his own classmate, Robin LaClerque, had broken his wrist skateboarding. He had a cast. He also had screws in his bone. After a while the novelty wore off and it became a major pain in his ass. Walter hoped nothing like that would happen to him. He thought of a word he had heard. Freewheeling. He thought he understood what it meant. That’s what he wanted to be – freewheeling.

End: 004

005:

The ride from Walter’s home to the school in the morning took the bikers up and down several hills. They had enough time to walk their bikes up the steepest of the hills. Anyway, though the boys- Walter and Tony Hoagland- were strong enough to ride up the hill, they were joined this morning by Sally Herman, another neighbor, and being a girl, she stopped in mid-conversation and started walking her bike. The boys, out of courtesy, stepped off their bikes, and hiked up the hill, arranged as a pair on her left.

Sally was a year older, in the sixth grade. All three lived within a half-mile of one another. Sally’s parents owned two horses, which they kept in a barn. On occasion, Walter got to ride Pepper, the horse with the gray coat and black spots.

Burleson had to rush his throw, Tony was saying.

He came up with the ball too fast. Kuiper’s pretty fast, Walter observed.

Winning run on third. It always happens when you walk the leadoff guy in the ninth.

Are you mad at Nelly? Sally broke in, directing her question at Walter. Nelly was the third grader who took part in the tree climbing incident that resulted in Chris’ broken arm. Nelly was Sally’s younger sister.

Walter kept his eyes on the street as he pushed his bike. A car passed them. Mr. Croce beeped his horn and waved as he passed them. He was the local barber, and had the same last name as Jim Croce, the popular folk singer who had died two years earlier in a plane crash in Louisiana.

Huh, Walter?

I don’t know. I didn’t think about it, he grunted.

Did she do something? Tony asked. He really didn’t know much about the story; just that Chris had fallen out of the tree and broken his arm.

They were just climbing the tree and Chris fell. Sally made it sound rather normal.

Her and Viv were teasin him. Now Walter sounded nettled.

They didn’t think he was gonna fall. Jeeze. They didn’t push him or anything.

They said he was a baby. Now Walter turned his face toward Sally, but the three continued to push their bikes up the hill.

So, that made him fall? Just because they called him a baby?

Tony kept his mouth shut. This spat was getting interesting.

I don’t know, Sally. Chris is a little kid. Maybe he don’t know how to handle two bratty girls.

Sally stopped walking. She stared at Walter, narrowing her eyes. Two bratty girls? Are you gonna blame Nelly and Vivienne because your brother climbed a tree, and nobody made him, y’ know, an then he fell by himself. She held onto her handle grips tightly and squared her shoulders as she awaited his retort. Walter sort of liked her looks, her reddish hair and everything, but he knew from experience that she liked to argue, that she sometimes enjoyed creating dissension, often when there was no need for it. In his opinion.

We’re gonna be late for school, he said, and pushed his bike even more vigorously up the hill. Tony hurried after him, and Sally was forced to follow them.

Walter’s mind wandered. This was Mr. O’Connell’s room where math was taught, not one of Walter’s favorite periods. White-haired Mr. O’Connell was unpredictable, sometimes very serious about math, occasionally warm and humorous, but often, if his mood changed, he could become sarcastic and cantankerous. Some of his classmates reckoned his mood changes had something to do with his age or, they suggested, a lack of sex.

Four of Walter’s classmates were working on algebra problems on the blackboard. Mr. O’Connell stood behind them, watching silently. He often wore a dark blue suit with thin white stripes, and sometimes collected chalk dust, which angered him. Suddenly he saw how frowzy he appeared, not the dignified professional he sought to portray to the school. Walter had already done his stint at the blackboard, and had survived with minimal deprecation from his teacher, and now could settle down at his desk, his mind wandering back to the sharp words between Sally and himself, and to the vague sense that somehow he had been partially responsible for his younger brother’s misery.

Sally giving him a hard time. Like blaming Chris and defending those bratty girls. What was her problem? He hadn’t said anything about her sister to Sally. Not initially, anyway. Not until she started asking him if he was mad at Nelly. Nelly was not on his mind until then. He had been talking about the ninth inning defeat suffered by the Red Sox.

He had only told his parents about some of the mischief Nelly and Viv were guilty of, like breaking Old Man Leggett’s window, stuff like that. Chris had been with the girls part of the time, and had been sternly questioned about the window just because someone had seen him aimlessly breaking bottles with rocks on another occasion. Chris should just stay away from those girls, Walter had told his mother and father. They just like to get him in trouble. Had his parents reported his story to Sally and Nelly’s parents?

Sitting there in math class he reflected more deeply about Sally. She had sort of a seventh grade boyfriend, Duane, whom Walter generally disliked. Duane messed with several other girls, too- flirted- he guessed might be the correct word. That was a word her heard in movies a lot, but not often at his school. Sally’s older brother, Nick, had been friendly though, even teaching Walter the rudiments of horseback riding. Now, with Chris’ broken arm, the whole picture seemed to be changing. Walter wondered if he would be invited to the Herman farm anytime soon. Would there be any horseback riding in his future?

End of 005

006:

Sleep was impossible. Walter hated when they fought downstairs in the kitchen. Their strident words easily reached him upstairs. His father with his harshness; his mom with her shrill howling. Walter gave a thought to how much Chris must be suffering, probably sobbing quietly in his small bedroom next to the kitchen. His arm must be aching worse than usual. But his brother wouldn’t dare cry for help, especially when their arguing was largely connected to him.

- First you let him climb a tree unsupervised! Then—

- My God, Hank! I was making beds! And—

- Yeah, yeah, yeah—I heard that fifty times—

- Because that’s the fact!

- I know what you do at eleven o’clock—you’re watching the fuckin soap opera!

- You’re a nasty bastard, Hank!

- And today you leave Chrissie alone with Mrs. Crossley!

- So I could earn a little money for my family! Her voice rose with indignation. Walter imagined that now tears were starting to fall from his mother’s eyes. – And stop the vile language! The boys can hear you all over the house. You’re complaining about money all the time. MONEY, Walter thought. It always comes down to that. – so I try to help. Roberta called. Penny likes me to do her hair. She requested me!

- Yeah, while Chris needs you, Lucinda. More than Penny Robertson, for chrissakes!

As Walter’s mother’s wail rose another decibel, his father’s roar surpassed it. - And Mrs. Crossley is getting into my Jack Daniels!

- You can’t prove that, Hank! Why’re you so cruel!

- Who else? You? Walter? I know how much was in that bottle! Then his father switched tangents. – It must’ve took Chris at least twenny minutes to climb that high. Twenny minutes! You couldn’t take a look out the window in twenny minutes? They got commercials on those soap operas, don’t they? Sure they do! You couldn’t get off your ass?

Then, Walter could actually hear his mother’s sobs. That was more painful than the shouting. I’m not cruel, Lucinda—I’m responsible, he could hear his father say, but he was no longer shouting. Our little boy could’ve bashed his skull in—

- He can hear you, for God’s sake! It was not a shout, but a loud hiss from his mother, audible all the way upstairs. Walter wrapped his pillow around his head in an attempt to block his ears. The thought flashed through his mind that Chris would try to similarly block out the fighting, but with his cast, it might be impossible. The tears helped silence the fight. He felt his own eyes gathering moisture. Then he heard the back door slam.

He heard the Ford start up out back. His father would take out his anger or hopefully extinguish it outside somewhere. Walter didn’t know where his father would go. In fact, he didn’t want to know where his father was going. That might be too much knowledge at this stage of his life.

Walter knew his mother loved her soap operas. If he watched one with her sometimes when he stayed home from school with a cold, he found them prohibitively boring. Men and women were repeatedly arguing. Maybe that’s where adults learned the habit. But he also believed that his mom was a good mother, at least in comparison with a lot of mothers he met in other homes. She kept the house clean; she often worked in the garden; his clothes were clean and pressed. Sometimes he gathered the laundry off the clotheslines and brought them into the basement where she ironed them. If the housework was under control, she sometimes worked at Roberta’s salon, which earned her some money and seemed to give her pleasure as well.

Admittedly, his father worked even harder and longer, which appeared to give him a kind of grim satisfaction. Some days he started in the garden by 6 a.m., and then went to Uncle Howie’s lumberyard by 11. Frequently, he didn’t get home until 6 p.m. where his family and dinner awaited him. If the food had cooled because he was later than expected, Hank muttered or frowned. Griping was not uncommon. He poured some Jack Daniels into a glass.

Walter made his mind seek out happier moments with the family before he could gradually drift off into sleep.

End of 006

Published on December 09, 2015 20:55

October 26, 2015

Yin and Yang at the End of the World

Yang & Yin at the end of the world

Peter Alexander Uncategorized 2 0

The themes that have interested me the most during the first decade of the twenty-first century have been about the empowerment of women, and the possibility that spiritual evolution may advance in a manner just in time to save our planet from destruction.

You find these themes to one degree or another present in all my books, even my series for children – Mubu, the Little Animal Doctor™. Mubu is a heroine, and she is also a real person. It is not simply fiction that this little girl rescued, raised and made friends with a variety of birds and animals in remote northern Thailand. I have seen first hand the magic that the woman who was once Mubu can perform with the animals she protects today.

Children often have the time and capacity to devote great love for the animals that enter their lives. It has, therefore, been my wish to see my Mubu books inspire more children all over the world to realize that they have the ability to make a difference in the lives of so many disadvantaged animals.

Beyond all the obvious “end of the world” scenarios that appear in ‘Beneath’ (which required copious research to make those consequences not only possible, but frighteningly plausible), the book at a deeper level is about balancing the male and female energies on our planet. The state of Yang and Yin at the end of the world.

Stated another way, if the planet is to survive its current descent, the patriarchy can no longer dominate life on earth as it has for centuries. The current political-economic-social disasters that reveal themselves daily, together with earth changes and climate change, can be seen in large part due to the existing imbalance between male and female influences.

(Probably I should add now that this is not a diatribe about men being bad and women good. When we speak about yang and yin, there is the assumption that all men and women possess aspects of both male and female energies.)

The main characters in ‘Beneath’ who survive the cataclysm that befalls earth are a 47-year-old writer-martial arts expert named Dennis, and his 15-year-old niece, Aggie. Dennis is strong, worldly and noble. Additionally, he is often somewhat professorial, so perhaps we can suggest he is an ‘Indiana Jones’ archetype.

Aggie is a very bright and sensitive girl, who has been influenced by Dennis to learn martial arts, and therefore she has attained a level of confidence in herself not frequently seen in teenage girls. However, she never dreamed she would be living underground with Dennis and his cat Gilda after the cataclysm destroyed much of humanity.

The archetypal older man and teenage girl must survive together for five years, searching for wild edible vegetables and hunting animals above the ground during the day and spending seemingly endless nights in their confined shelter beneath the ground. As Aggie grows toward womanhood, the gender balance experiences many subtle and not so subtle changes.

In ‘The Girl Who Threw Stars,’ the story of a very different kind of male-female dichotomy plays out in sometimes horrific terms in northeastern Thailand.

Though the heroine, Kanthida, a 26-year-old Bangkok prostitute, is flawed, she nevertheless attempts to observe Buddhist principles, while avoiding her ex-husband’s journey of vengeance. Kanthida can be ruthless herself, even as she manages narrowly to resist killing her deadly adversary.

The book’s genre blends magical realism and horror. Even though the bloody body count rises as Major Wororat, a Thai policeman who operates fluidly on both sides of the street, chases his former wife, spirituality emerges as a countervailing theme.

In the realm of spirit, death does not end certain forms of existence on earth, for the evil as well as the sublime.

Peter Alexander Uncategorized 2 0

The themes that have interested me the most during the first decade of the twenty-first century have been about the empowerment of women, and the possibility that spiritual evolution may advance in a manner just in time to save our planet from destruction.

You find these themes to one degree or another present in all my books, even my series for children – Mubu, the Little Animal Doctor™. Mubu is a heroine, and she is also a real person. It is not simply fiction that this little girl rescued, raised and made friends with a variety of birds and animals in remote northern Thailand. I have seen first hand the magic that the woman who was once Mubu can perform with the animals she protects today.

Children often have the time and capacity to devote great love for the animals that enter their lives. It has, therefore, been my wish to see my Mubu books inspire more children all over the world to realize that they have the ability to make a difference in the lives of so many disadvantaged animals.

Beyond all the obvious “end of the world” scenarios that appear in ‘Beneath’ (which required copious research to make those consequences not only possible, but frighteningly plausible), the book at a deeper level is about balancing the male and female energies on our planet. The state of Yang and Yin at the end of the world.

Stated another way, if the planet is to survive its current descent, the patriarchy can no longer dominate life on earth as it has for centuries. The current political-economic-social disasters that reveal themselves daily, together with earth changes and climate change, can be seen in large part due to the existing imbalance between male and female influences.

(Probably I should add now that this is not a diatribe about men being bad and women good. When we speak about yang and yin, there is the assumption that all men and women possess aspects of both male and female energies.)

The main characters in ‘Beneath’ who survive the cataclysm that befalls earth are a 47-year-old writer-martial arts expert named Dennis, and his 15-year-old niece, Aggie. Dennis is strong, worldly and noble. Additionally, he is often somewhat professorial, so perhaps we can suggest he is an ‘Indiana Jones’ archetype.

Aggie is a very bright and sensitive girl, who has been influenced by Dennis to learn martial arts, and therefore she has attained a level of confidence in herself not frequently seen in teenage girls. However, she never dreamed she would be living underground with Dennis and his cat Gilda after the cataclysm destroyed much of humanity.

The archetypal older man and teenage girl must survive together for five years, searching for wild edible vegetables and hunting animals above the ground during the day and spending seemingly endless nights in their confined shelter beneath the ground. As Aggie grows toward womanhood, the gender balance experiences many subtle and not so subtle changes.

In ‘The Girl Who Threw Stars,’ the story of a very different kind of male-female dichotomy plays out in sometimes horrific terms in northeastern Thailand.

Though the heroine, Kanthida, a 26-year-old Bangkok prostitute, is flawed, she nevertheless attempts to observe Buddhist principles, while avoiding her ex-husband’s journey of vengeance. Kanthida can be ruthless herself, even as she manages narrowly to resist killing her deadly adversary.

The book’s genre blends magical realism and horror. Even though the bloody body count rises as Major Wororat, a Thai policeman who operates fluidly on both sides of the street, chases his former wife, spirituality emerges as a countervailing theme.

In the realm of spirit, death does not end certain forms of existence on earth, for the evil as well as the sublime.

Published on October 26, 2015 22:01

•

Tags:

mubu, women-s-empowerment

October 14, 2015

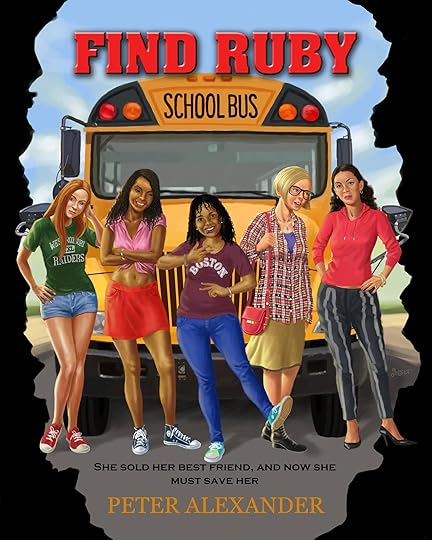

Find Ruby

Find Ruby

Synopsis

Star Madison escapes just after her sixteenth birthday. She disappears from South Roxbury, from Hannah Dustin High, her Girl Gang collapsed and scattered . Brienne, her classmate, her lover, herself a young genius like Star, is the only one who remains at Hannah Dustin. Becky, now fifteen, has been vindicated for shoving a letter opener into the throat of Alfredo Maysley, Star’s Central American mentor and sometimes lover, causing his death. It was obviously self-defense. Becky has gone to a different school in Boston to avoid unwanted notoriety. Ruby and Pearl, sisters, the two original black members of Star’s coterie, are being trafficked for sex somewhere in the southern U.S.

Star has fled to New York City, the Lower East Side. She is wanted by Boston police for being the leader of the girls’ ‘business’ that led to the shooting and death of two Boston detectives in addition to the killing of Maysley. The fact that the two deceased cops were criminal associates of Maysley did not lessen the determination of Boston police to find and punish Star.

Star, however, is smarter than most people. She possesses a genius I.Q., and somewhat of a nihilist personality. She finds a place to hide in New York, and spends many of her hours at Pace University where she audits a course in philosophy.

Meanwhile, two black Boston police detectives, Monroe Cummings and Clayton Dees, have arrived in Bowling Green, Kentucky, to investigate the murder of a black teenage girl, who has been identified as Pearl Baxter, one of Star’s original cohorts. Once they discover that the dead girl is actually Pearl, they begin to try track Ruby, her younger sister, who is rumored to be a sex slave somewhere in South Carolina.

Cryptically, Brienne gets word to Star in New York about Pearl’s murder and Ruby’s crucible. For the first time she can remember, Star feels guilt, and even a touch of shame. These were my friends, she realizes. They followed me. She decides that she will take responsibility for what is happening, and at least will find Ruby. And save her.

Star has partial knowledge about the sex trafficking network that the police do not possess. She also has consummate belief in her own abilities. She takes the AMTRAK down to Washington where she connects with a young man who once worked as an intermediary for Maysley and herself. Through him, she learns how to track down one Baby Cabrera, a 20-year-old pretty boy leader in the extremely vicious MS-13 gang that proliferates across U.S. cities, having originated in El Salvador.

Maysley had once hired Baby and his goons to control clients of the sex trafficked girls. After Maysley was killed, Baby had taken over his business. Pearl and Ruby were two of the teenage girls ensnared by the gang.

In the dark of night in D.C., Star shocks Baby and his cousin, Fausto, at the construction site for an office building, where the gang is supplying girls for after work entertainment for laborers. Although all the young machete-weilding MS-19 gangbangers have the most hideous reputations for violence, there is something about Star that fascinates Baby. Maybe he remembers how much Maysley, his hero, had admired the teenager, called her a genius. She asks Baby why he is wasting his time with laborers, when she can lead him to substantial money by sending rental girls overseas. In addition to a business partnership, Star wants Ruby returned to her.

In Boston, Brienne uses her considerable computer skills to create documents that appear to come from a Nigerian millionaire. The paperwork includes a contract with Star Madison to provide teenage American girls (preferably blonde) for a rental period. Star shows the documents to Baby Cabrera. He agrees to her terms. He knows where Ruby is. Although she escaped her controller in a traffic accident in Charleston, S. Carolina, he has a method for tracking her. Accompanied by cousin Fausto, they will drive to Charleston to locate Ruby.

Meanwhile, Ruby has found an empty home, repossessed by a bank, on Seabrook Island in South Charleston. With her is an eleven-year-old North Carolina girl named Given Lowery, another sex slave, who was forced to perform for men in tandem with Ruby. Given is traumatized and never speaks. Ruby cares for her like a mother. The older girl will not contact the police, fearful of their connections with MS-13. She finds various empty homes where she can break in and secure food for herself and Given. Meanwhile both girls find occasional solace at the nearby beach and ocean.

Detective Sergeant Cummings and Detective Dees have now arrived in Charleston, having found the trail of the slaver who was holding Ruby and Given before the car accident. Though they find their counterparts among the Charleston police devious, the Boston policemen utilize old-fashioned, by-the-book police work to direct their search for Ruby to South Charleston.

Meanwhile, during the long drive from D.C. to Charleston, Baby Cabrera ‘s inherent paranoia, emotional dissociation and deep-seated misogyny begin to create antipathy between himself and Star, whose superiority complex is seldom curbed. This would-be partnership does not appear to promise much durability.

All roads lead to Charleston as the main players unknowingly maneuver toward one another and a climax that will be both bloody and volatile.

©Peter Alexander 2015

Synopsis

Star Madison escapes just after her sixteenth birthday. She disappears from South Roxbury, from Hannah Dustin High, her Girl Gang collapsed and scattered . Brienne, her classmate, her lover, herself a young genius like Star, is the only one who remains at Hannah Dustin. Becky, now fifteen, has been vindicated for shoving a letter opener into the throat of Alfredo Maysley, Star’s Central American mentor and sometimes lover, causing his death. It was obviously self-defense. Becky has gone to a different school in Boston to avoid unwanted notoriety. Ruby and Pearl, sisters, the two original black members of Star’s coterie, are being trafficked for sex somewhere in the southern U.S.

Star has fled to New York City, the Lower East Side. She is wanted by Boston police for being the leader of the girls’ ‘business’ that led to the shooting and death of two Boston detectives in addition to the killing of Maysley. The fact that the two deceased cops were criminal associates of Maysley did not lessen the determination of Boston police to find and punish Star.

Star, however, is smarter than most people. She possesses a genius I.Q., and somewhat of a nihilist personality. She finds a place to hide in New York, and spends many of her hours at Pace University where she audits a course in philosophy.

Meanwhile, two black Boston police detectives, Monroe Cummings and Clayton Dees, have arrived in Bowling Green, Kentucky, to investigate the murder of a black teenage girl, who has been identified as Pearl Baxter, one of Star’s original cohorts. Once they discover that the dead girl is actually Pearl, they begin to try track Ruby, her younger sister, who is rumored to be a sex slave somewhere in South Carolina.

Cryptically, Brienne gets word to Star in New York about Pearl’s murder and Ruby’s crucible. For the first time she can remember, Star feels guilt, and even a touch of shame. These were my friends, she realizes. They followed me. She decides that she will take responsibility for what is happening, and at least will find Ruby. And save her.

Star has partial knowledge about the sex trafficking network that the police do not possess. She also has consummate belief in her own abilities. She takes the AMTRAK down to Washington where she connects with a young man who once worked as an intermediary for Maysley and herself. Through him, she learns how to track down one Baby Cabrera, a 20-year-old pretty boy leader in the extremely vicious MS-13 gang that proliferates across U.S. cities, having originated in El Salvador.

Maysley had once hired Baby and his goons to control clients of the sex trafficked girls. After Maysley was killed, Baby had taken over his business. Pearl and Ruby were two of the teenage girls ensnared by the gang.

In the dark of night in D.C., Star shocks Baby and his cousin, Fausto, at the construction site for an office building, where the gang is supplying girls for after work entertainment for laborers. Although all the young machete-weilding MS-19 gangbangers have the most hideous reputations for violence, there is something about Star that fascinates Baby. Maybe he remembers how much Maysley, his hero, had admired the teenager, called her a genius. She asks Baby why he is wasting his time with laborers, when she can lead him to substantial money by sending rental girls overseas. In addition to a business partnership, Star wants Ruby returned to her.

In Boston, Brienne uses her considerable computer skills to create documents that appear to come from a Nigerian millionaire. The paperwork includes a contract with Star Madison to provide teenage American girls (preferably blonde) for a rental period. Star shows the documents to Baby Cabrera. He agrees to her terms. He knows where Ruby is. Although she escaped her controller in a traffic accident in Charleston, S. Carolina, he has a method for tracking her. Accompanied by cousin Fausto, they will drive to Charleston to locate Ruby.