Clyde Dee's Blog, page 21

September 11, 2016

Why I am Motivated to Write

Perhaps, early in my career as a mental health counselor, I couldn’t even see the untold story. Landing my second job gave me the financial power to leave a ghetto apartment in the most murderous city on the East Coast. Since I was only just entering a Master’s Program, I felt extremely privileged. As a result, I aligned myself with my supervisor and other more experienced workers. Without credentials, I was focused on working with people who would get my back.

One day, I received a client and was ready to get to work on housing issues, when I found out that she came attached with a more experienced case manager. Though not very talkative, she did tell me very clearly that she did not want to go to a particular boarding home, the largest such facility in the county. When I talked to the case manager who would later be my supervisor when I got promoted, he was clear about the woman’s future. She had to go to the unwanted boarding home.

“Wow, that girl is really sick!” I heard the coworker who worked the graveyard shift at the crisis house say.

“I don’t get it,” I said, “I don’t see why she can’t live where she wants to. I help other people find housing, why can’t I help her.”

“That girl is very sick, I can just tell by the way her eyes roll to the side” said my co-worker

I deferred to experience. Sure I had been hospitalized for six months myself, but I knew better than to make waves. The woman was shipped away to the very place she most did not want to go. She had been right not to trust any of us. For us, she was just protocol.

Once I graduated my Master’s program and was promoted, I visited the infamous boarding home which was buried in the New Jersey Pine Barrens in the far reaches of the county. Out in the pines, there were few stores, lots of sand and aged pine trees, whose growth was stunted by fire. The pines were where most boarding homes were located. I admired the scenery as I drove out.

The infamous boarding home’s one-story buildings were made of quarter inch plywood and styled in rows like chicken coops. There was no insulation from the elements in any of the buildings. They were long and full of small rooms with cots and no furniture. At the end of each row of rooms there was an open rec room where open vats of warm, iceless bug juice sat out under the dim lighting. There were no fans to drown out the buzz of the flies. These inside rooms reeked of sickness. The chipping linoleum floors were being mopped with cheap chemical stink water that reinforced the sick feel. Almost all the clients were either gone to a day program or had walked the three miles to the store. I could not even begin to picture what the place looked like when it was full.

When I finished I followed the owner to the front office. The owner’s daughter had been in my sister’s class at our posh private school before anorexia had lowered my social standing. Back at the office, the owner had barraged me with gossip and information about the school. By then I was learning to undermine the subservience façade of the mental health client. As a result, I found myself struggling not to be offensive to this woman who had helped pay for my rearing.

Once freed to collect my thoughts, I recall betting to myself that they treated mentally ill better back in the Middle Ages. So many good people I had worked with for years were living lives like this and I had never given it any consideration.

In a year, I made enough money to fund a move to the west coast. Within six months of moving, I made a risky job transfer into setting up services in a section eight housing authority facility. When I found out my supervisor had a cocaine habit, I stopped heeding her. Like a vigilante. I leaked info openly to a community activist and to newspapers and was starting to face unforeseen levels of threats.

One day, a resident who had pointed out the local drug kingpin to me, told me that I was deeply loved by all the residents, even the shady ones, but that they were all worried that I would end up becoming a resident of the building myself.

Within a week, after an unsuspected threat from a friend from my ghetto days who, it turned out, was connected, I was picked up out of a ditch on a mountain pass outside of Butte Montana. I had been harassed by police for the past two days since they had halted my escape to Canada. Finally, I surrendered to them.

Two months in, just when I had finally started to accept the very poor treatment I was receiving, I was transferred to the most chronic unit. The temperature inside was below freezing. There would be icicles inside the window that sat above my head. It was almost as bad as the boarding home in South Jersey. When I first entered those dank halls, I felt destined to behave with the subservient merriment of the thirty year residents. I was given old, dirty clothing so that I could layer up among the crowded halls. My appearance and sense of self declined. Fungus off the bathroom tiles grew under my toenails and warts covered by hands.

Now, I am a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist who works in an inner city day program. I also am an award winning author of a memoir that details my untold story. Much of the book is about coming out of “psychosis” while working at the only place that would hire me, an Italian Delicatessen.

I write because now I see that there are so many untold stories out there. I write because twenty years ago a woman was committed to squalor and I did nothing. I write because I once was so arrogant so as to think it couldn’t happen to me. I write to better express love and support to the people I work for. I write because I know firsthand what it feels to be demeaned. I write because I believe that loss of housing and mental health can happen to any of us regardless.

In this age of heightened social disparities, the propensity for dehumanizing people is on the rise. Now that the public is finally able to see the way that black men are shot indiscriminately by police. Now that American prisons are disproportionately filled with mentally ill, political-prisoners of color. Now we all know that years of slaughter in the Middle East can be traced back to fabricated evidence. Still, we blame all violence on the mentally ill, immigrants, and African-Americans. We think we can make ourselves safer by taking more power.

Already there are too many stories left untold.

I write to tell them.

Why I Write to Champion the Untold Story

Perhaps, early in my career I couldn’t even see the untold story. During my second job, I worked at a day program that was connected to a 30 day crisis house. I worked as if I were a choir boy singing the words to Amazing Grace without understanding its meaning. Individuals could seek respite from housing emergencies and focus on their mental health. They joined individuals from the community who also attended the day program. I ran groups and helped many find affordable housing placements.

Landing the job gave me the financial power to get myself recruited into a community house with some vague acquaintances so I could leave a ghetto apartment I maintained for five years previous. Since I was only just entering a Master’s Program, I felt extremely privileged to hold this responsible job. As a result, I tended to align myself with my supervisor and other more experienced workers and learn the ropes from them. Without credentials, I was focused on survival and that meant working with people who would get my back in case something happened.

One day, a client who I worked with wanted help finding housing. I was ready to get to work, and then I found out that she came attached with a more experienced case manager. Though she was subservient and not very talkative, she did tell me very clearly that she did not want to go to a particular boarding home, the largest such facility in the county. When I talked to the case manager who would later be my supervisor when I got promoted, he was clear about the woman’s future. She had to go to the unwanted boarding home.

“Wow, that girl is really sick!” I heard the coworker who worked the graveyard shift at the crisis house say. The co-worker had been a single mother who was clear that she still pampered her son, a prison guard. She would really lose it a few years later when her son died mysteriously.

“I don’t get it,” I said, “I don’t see why she can’t live where she wants to. I help other people find housing, why can’t I help her.”

“That girl is very sick, I can just tell by the way her eyes roll to the side” said my co-worker

I deferred to experience. Sure I had been hospitalized for six months myself, but I knew better than to make waves. The woman was shipped away to the very place she most did not want to go. She had been right not to trust any of us and let us know she was hearing voices. It was just protocol that the case manager makes the decision. I went on, just doing as I was told.

Once I was degreed and promoted, I visited the infamous boarding home which was buried in the Pine Barrens in the far reaches of the county. Out in the pines, there were few stores, lots of sand and aged pine trees, whose growth was stunted by fire. The pines were where most of the county’s boarding homes were located. I admired the scenery as I drove out to the large boarding home the first time.

The one-story buildings were made of quarter inch plywood and styled in rows like chicken coops. There was no insulation from the elements in any of the four or five buildings. They were long and full of small rooms with cots and no furniture. At the end of each row of rooms there was an open rec room where open vats of warm, iceless bug juice were just sitting out under the dim lighting. There were no fans to drown out the buzz of the flies. These inside rooms reeked of sickness. The chipping linoleum floors were being mopped with stink water mixed with cheap chemicals that reinforced the sick feel. Almost all the clients were either gone to a day program or had walked the three miles to the store where they bought their smokes at. I could not even begin to picture what the place looked like when it was full.

When I finished meeting with my client I followed the owner to the front office to check in on some business. The owner’s daughter had been in my sister’s class at our posh private school. I had grown up in privileged contexts, my parents both private school teachers. Back at the office, the owner had barraged me with gossip and information about the school.

When this had started in front of the client, I had been ashamed to have the privilege of my past revealed. By then I was learning to undermine the subservience that clients’ showed me, not exacerbate it. As a result, I found myself struggling not to be offensive to this woman who had helped pay for my rearing.

Once freed to collect my thoughts, I recall betting to myself that they treated mentally ill better back in the Middle Ages. I was stunned by the fact that so many good people I had worked with for years were living lives like this and that I had never given it any consideration.

In a year, I made enough money to fund a move to the west coast. Within six months of moving, I made a risky job transfer into setting up services in a section eight housing facility. When I found out my supervisor had a cocaine habit, I stopped heeding her. I started to act like a vigilante. I started to community build. I leaked info openly to a community activist and to newspapers and was starting to face unforeseen levels of threats.

One day, a resident who had pointed out the local drug kingpin to me, told me that I was deeply loved by all the residents, even the shady ones, but that they were all worried that I would end up becoming a resident of the building myself. They were worried about losing their housing too. That kingpin had been employed as a social service worker and frequently made eyes at me.

Within a week, after an unsuspected threat from a dear friend, I was picked up out of a ditch on a mountain pass outside of Butte Montana. I had been harassed by police for the past two days since they stopped me trying to escape to Canada. Finally, I surrendered to them.

Two months in, just when I had finally started to accept the very poor treatment I was receiving amid menacing mafia thugs and crazy people, I was transferred to the most chronic unit. The temperature inside was below freezing. There would be icicles inside the window that sat above my head. The conditions were almost as bad as the boarding home in South Jersey. When I first entered those dank halls, I, again, couldn’t believe that they treat mentally ill like this. Now I was victim to it feeling destined to behave with the subservient merriment of the thirty year residents. I was given old dirty clothing so that I could layer up among the crowded halls. My appearance and sense of self declined. Fungus off the bathroom tiles grew under my toenails and warts covered by hands.

Now, I am a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist who works in a day program in the historical section of a city hospital in Oakland CA. I also write to help create a culture for other people like me who have had their life severely impacted by stigma and discrimination. My first book is a memoir detailing events that led into that backward of a state hospital. Much of the book is about my recovery coming out of “psychosis” while working at the only job I could find, a deli worker at an upscale Italian Deli. The Midwest Book Review has said my memoir is “deeply personal and impressively well written.” Reader’s Choice and Reader’s View have likewise given me five star reviews. My current effort is more of a technical book that tries to better define what “psychosis” really is in order to promote healing and recovery.

I write because now I see that there are so many untold stories out there. I write because twenty years ago a woman was committed to squalor and I did nothing. I write because I once was so arrogant so as to think it couldn’t happen to me. I write to learn how to appreciate, love and support the people I work for. I write to prepare myself for any type of survival that is to come. I write because I know firsthand how devastating it feels to be demeaned like a client. I write because I believe that loss of housing and mental health can happen to any of us regardless.

In this age of heightened social disparities and the disintegration of the middle class, the human propensity for dehumanizing things is on the rise. Now that the public is finally able to see the way that black men are shot indiscriminately by police. Now that we can watch television series and see how prisons are disproportionately filled with mentally ill, people of color, and many essential political prisoners. Now we all know that years of slaughter in the Middle East can be traced back to fabricated evidence. And still we listen to and promote lies. We blame it on the mentally ill, the immigrants, and African-Americans. We think we can make ourselves safer by taking more power. Already there are too many stories that happen in our country that are left untold.

I write to tell those stories.

July 5, 2016

Reflections on Overcoming Stigma to Pay Forward

Back when I was just a yuppie, I learned a few points of wisdom that I want to pay forward to some mental health academics and administrators.

I was learning to chop cheese steaks at a Korean owned deli and instantly enamored with this mentor on the grill, Mister Ray Gee. The deli was located just across the river from downtown Philadelphia, in the North Camden ghetto. This Mister Ray and I were just meeting. We were both the same skin-and-bones size, our last names went together in rhyme, and any middle aged man who didn’t have a gut was an inspiration to me.

Mister Ray took one look at me and said, “Wow you are an Asshole! But don’t worry, it’s not your fault! You were just raised that way!”

Without missing a breath, our supervisor, a short and stout man who we called Doc set me to work scraping grease off the floor with a razor blade. I dove into the work very comfortable with what had just occurred. I felt a little charge with the challenge. On my knees I scraped and scraped to overcompensate.

I immediately found myself thinking about how when I returned to school from four months of incarceration in two different mental health hospitals, I had only scoffed when my peers, the majority of whom had previously bullied me, welcomed me back with a little gift certificate. Though it wasn’t all that unusual of a gesture for peers at a private Quaker school to extend, I had only acted humiliated. I had to acknowledge that it was asshole behavior.

I thought even more about the sessions the family had in Salvador Minuchin’s reputable inpatient clinic. One day in session, my Mom openly admitted that she shared the content of a session back to a work colleague. My Mom worked at the school I attended. She later gave me evidence that my private information was filtering down to the jury of my peers who were sorry and praying for her. When I returned to school much of this would appear to be confirmed. Worse no therapist on the hospital staff seemed to acknowledge my perspective.

On my knees, I sensed Mister Ray was intuiting aspects of these complexities with his test. If I was willing to pass his test, he was giving me a chance to learn something new.

In the yearbook back at Quaker school, my peers lied about the local commuter school I chose to attend. They said that I went to the high cost prestige of Antioch University in Ohio. I was an honor student and I was making them all look bad when I moved to the ghetto with a twenty-five-year-old girlfriend and save my parents money. Communication in my family about finances is such that I still don’t know if I really had a choice.

A few months later, I got my second point of wisdom from Mister Ray. By this time I had learned to use the grill from him. I had heard about his sexual exploits with white girls without judgment. I had aptly proven that outside work I was just a book worm in the library, but could curse. And though it was true that by that time he knew I lived with roaches to escape from an abusive relationship, I think what really earned me respect was my willingness to let him con me into driving him uptown after work to cop.

In any case, he decided to help me. He said, “Boy, you have got to work smarter, not harder.” It became a mantra along with his nickname for me, Nervous Norton.

Again, I felt profoundly understood. It wasn’t that I marveled because I didn’t expect anything from him. We had fallen into a pattern of respect. With few words and resilience of spirit he inspired a spiritual healing within.

As a man with significant learning disabilities, I couldn’t afford to immediately practice Mister Ray’s second lesson. When I would be a graduate and fledgling social worker I would have a habit of positioning myself beneath supervisors as I worked my way through a Master’s Program and carrying out their will. This worked fine until I graduated and got hired by a supervisor who also sustained a cocaine habit in a west coast city. I became radicalized and started breaking standard drug war codes of behavior in a section 8 housing project. This caused me to believe that I was being followed. I ended up incarcerated in an old order state hospital. It took two and a half years of poverty, but I eventually would recover. In order to recover I would need to learn how to do things like honor my mother in spite of those perceptions I had back in high school. I also had to stop relating to all white people as though I was Mister Ray. Lesson learned?

It wasn’t till six years after I recouped my career that I actually started to use Mister Ray’s well remembered advice. I started running groups about surviving “psychosis” using my own experience. I started my own personal practice of keeping in real in therapy.

Perhaps it was unique privilege to be taught points of wisdom by Mister Ray. They continue to help me see through the lies and shortcomings that currently limit our mental health field, evidence based practice and the medical model. I even see through elements of cultural bias in some anti-establishment rhetoric.

Sadly, Ray and Doc had only lasted a few seasons before they both quit because of becoming disgruntled with the Korean mobster management and oppression. I certainly didn’t blame them even though I ended up losing touch. At the Deli, stale cereal sold for seven dollars a box and there were no supermarkets within a ten mile radius. Neighborhood contacts reported that Doc, who had used unacknowledged expertise to diversify the menu, had a subsequent binge on crack.

I ended up partnering with a similarly aged cohort from the neighborhood because I did need the money. My partner and I ended up mentoring youth beneath us. They had a choice, I would learn, between working with us under the table, and working to sell crack under the bridge. Some didn’t have longevity, but several did. For several years they were my family and social life.

Though I am well aware that not all academic and administrative folks need a lecture about mainstream paradigms, now that I am advocating for the development of an out of the box program in an utterly oppressive system, I find many who do. I believe we can train individuals who have experienced “psychosis” and are on the streets to run support groups. I have helped prove this could be done, but not everyone wants to listen.

At work in an inner-city program, I do therapy with good Mister Ray people who have more beauty in their hearts and suffering in their bones than me, but who are rendered immobile and impoverished. I believe a lot less harm could be done. I believe solutions exist that can transform the system from being a cotton industry to a soil saving industry of mixed nuts. I think of Mister Ray’s wisdom and experience a lot as I face those who defend those stale seven dollar boxes of cereal paradigms that fail people.

In my next out-of-the-box book I am trying to pay forward the things that people I know who are like Mister Ray keep teaching me. I often feel torn in my gut by a massive disconnect I perceive going on in society. Like most writers these days I wonder if my work will ever get seen and I write blogs to try to find my audience. I often find my message not deemed appropriate for academic blog sites.

My work has ranked high in awards, even when I don’t quite win and when a judge reflects stubborn stigma in the comments. I don’t write to be insulting, but not everyone is motivated to overcome the stigma I see. I continue to feel the wisdom of all the Mister Ray people I know can make the mental health industry healthier if the industry was willing to listen. I wish there were not such immense barriers to working together. Ultimately, to survive, we all need to minimize the divisive cognitive distortions that stigma bestow. Sometimes I wonder if other people of privilege are capable of coming off their pedestals to see the way that stigma so radically distorts so many aspects of our lives.

July 2, 2016

Goodreads Giveaway

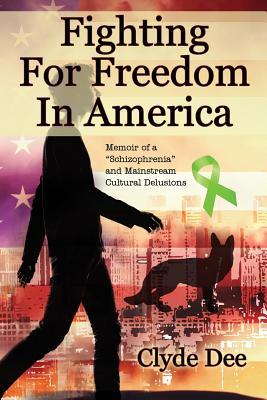

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Fighting for Freedom in America

by Clyde Dee

Giveaway ends September 11, 2016.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/widget/193006

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/27013994

June 12, 2016

“If you don’t know the history of the author than you don’t know what you are reading”

I am a Caucasian Quaker male with a history of an eating disorder and complex trauma who grew up in a prestigious Philadelphia suburb, for whom the standard of care—police harassment, handcuffs that bruise, long-term hospitalizations, forced feeding, nurses you don’t know who come up and cut on you, a schizophrenia diagnosis, seclusion, underemployment, extorted therapy, cognitive therapy and social skills training—didn’t fit. I even found the style of therapy that I found least offensive was not all that helpful to me. However, in my journey, I have found that medication does help me as it was not forced on me. Some of the other standard of care experiences I have been able to put to use, but only after I healed from the trauma of them.

What has emerged for me is a broad historical perspective on concentration-camp realities. After all, for me it was working amid the needle-and-pipe politics a last resort section 8 housing project that triggered my “psychosis.” By the time I knew enough about the place to feel it was a concentration camp, I was getting threats that I would end up living in the project as a result of my non-corrupted advocacy. Indeed I had engaged in some meddlesome activities in the name of advocacy, arguing that they would only be considered meddlesome if I was in fact, like my therapist maintained, paranoid. Indeed, if I wasn’t defining myself as paranoid, I would have seen my behavior as meddlesome and likely not taken those risks. But I allowed myself to be bullied on multiple levels. I may have threatened people from a different culture who I liked and wanted to help. When I received a pointed threat from an ex-drug dealing friend on the east coast, who I explained my situation to, I got scared and tried to flee. It took me a long time to be mindful and heal from what transpired: it is documented in my first book, a memoir.

Fifteen years down the road, in order to have a sense of belonging in the world, I need to understand how the legacy of my life gets seen through the differing arms of my family. The wealthy sides of my family financially supported hermitic artists that were talked about in a hush; they collaborated with the members of more modest to clearly not discuss the invisible relative who had been lobotomized and institutionalized in past generations. Now I write under a pen name to shield my family from the enduring shame associated with my existence. While to some extent I still am invisible and devoid of recognition in the folklore of family Christmas reports, things are getting better. As my own family is healing from my exploits, I hope to help them transition bit by bit into a new era.

The life experiences most alive in my head consist of being locked up in urban centers and rural State Hospital circumstances, surviving ghettoized institutional roach-infested settings or barracks; working seasonal retail positions; being bullied by organized crime, police, various branches of law enforcement and mental health professionals, being silenced or alienated by wealthy family members who cannot accept the fact that I increasingly feel at odd with my culture of origins. And I am so lucky to have found work among people who invariably report similar experiences, whether they come from the insulated suburbs or the streets of East Oakland. This work affords me the ability to strike an empowered balanced home on the outside.

I consider myself an extremely lucky, guilty survivor.

While message receivers no longer get lobotomized and put permanently in asylum if they are law abiding, there has been a tendency for institutional realities to be sputtered and spit into zoned, ghettoized realities that circulate unnoted and unseen by many through the fabric of our nation. Having experienced or at least understood these realties in the raw, I go to work on an old institutional wing trying to imagine a culture where message receivers of all creeds and social status can fit in and work together for empowerment.

In over twenty years of professional experience providing mental health services, I have found, as I was taught in school, that navigating racial, ethnic, class, and gender bias in relationships can lead to powerful and authentic contact; yet I remain dumbfounded when I was destined for mental health clinics, that I was clearly not taught to me was how to navigate around the black market with respect or relate to individuals when they are “psychotic.” I knew I was prone to see things from a message receiving perspective as a helper and was always considered good at what I did; but it wasn’t until I chose to immerse myself in last resort lifestyles when I became “psychotic.” I became “psychotic” in order to avoid being killed for some of the meddlesome things I had done. I became “psychotic” because I went off of my low dose of anti-psychotic. On better days I think I became “psychotic” because god needed me to learn what it really meant so that I would stop treating people with eugenic concepts. I became “psychotic,” and believe me it was a shock. Yet ultimately, I couldn’t be more grateful.

I have disclosed my cultural background in much further depth in my first book. I have increasingly found that disclosing my cultural background is necessary to reach Oakland men and woman who are in message crisis. Indeed, sharing the specifics of my ideas of reference requires a frame of reference. And why should they take the risk if I am not well enough to talk about the specifics of my experience. Not only do I use the experiences I had with messages, but also I have to own that I got my degree as an isolated male with bulimia in the ghettos of Camden, New Jersey with a “Where’s Waldo” reputation (that’s one of the names that some neighbors called me.).

Indeed, for me, working in this context challenges I hope to challenge the cultural notion of the blank-slate therapists’ ability to work within oppressed cultures. Indeed an upstanding cultural success story who can tell you what to do may be what many “chronically normal” folk look for, but for some individuals in utterly oppressive circumstances, nothing can be more offensive.

Part of the aftermath of the Medical Model is a reality in which, subjects, like message receivers, like slaves and homosexuals, are medically pathologized and not even considered to bear a history or a culture or legitimate oppressed experience. It seems fitting that peoples pathologized as such don’t get to work with earthlings; traditionally, they get to work with perfect blank slates whom can heal their pathological circumstance (which supposedly will never go away,) without consideration for the cultural oppression of their history. I am no dummy, I am not here to challenge the medical model. I do not want a bullet in my head. Instead I’d propose we take back culture one at a time, one person at a time. In this context we need an underground movement that works with the mad machine which says it wants recovery, to deliver freedom to people one life at a time.

May 29, 2016

Tilling the Institutional Soil in Kraeplin’s Kingdom:

As many know, Emile Kraeplin (pronounced crap-land) formed the magical thoughts that are the basis of mainstream DSM propaganda that forms the businesses and billing systems that occupy the nation’s mental health. Though the idea that an observable behavior is the result of a specific brain dysfunction is more magical than proven, many feel it is best to uphold it to maintain social order. This will save jobs and maintain the power of political action committees that advocate for them, like the AMA the APA, and the big pharm PAC (pharmaceutical industry.) Still if people can grow anyway managing the manure in the pastures in effective manners if they learn to work together.

With a dominant discourse that assumes pathology, and exacerbates stigma myths that I have seen Patrick Corrigan define in lectures as: 1) danger; 2) developmental regression, and 3) loveable buffoonery; a sense of community can remain behind barb-wire confines of old institutional white walls, leaking urinals, in unheated or drug infested homes, sometimes tended with authoritarianism midst cigarette smoke, throughout days without a sense of meaning and purpose or inclusion in the monetary system.

Well-intended peoples who take home the money society prescribes for these hacienda communities may run patrol making assessments about what is real without an understanding of what the message experience is like. Such workers eyes may operate with a subsequent skewed sense of their own power and health and without being encouraged to study or understand the process of the culture they work with. As a result well-intended people may not always hold high regard for the likeliness of competence and recovery that exists therein.

The purpose of this work is not to set off a bomb in such communities. People trying to help may have had no training courses about what “psychosis” is and don’t realize that they may operate in manners that may exacerbate the condition. If they have had the experience of an abnormal psychology course like the one I took, the understanding of psychosis may be full of fact distorting twin studies and brain scans; and magical, eugenic, disease-oriented thinking.

Many helpers don’t seem to consider the idea that people do live meaningfully with the experiences. All must adhere to, and some internalize, mainstream magical thinking. There is the differential labeling system of oppression divides individuals into labels and may not encourage them to systematically look for the similarities they have with each other. In essence there is an unintended mentality of divide-and-conquer that starts with the language of labels as if the Mad were to look to each other for an explanation of what is happening to them, that their loved ones would never get them back.

This work asks participants to consider the traumatic effects of being harshly judged on the basis of a desperate behavior; then treated in potentially inhumane manners. This work envisions a system that is not hell bent on dominating and bullying these behaviors into change via punishment. It looks at the manner in which the current social system oppresses and marginalizes. Mainstream supporters, often impassioned toward bullying because they are fearful that if they don’t, they may cause irrevocable brain damage; social loss; or lead to permanent incarceration; or homelessness. Many such helpers may later look at the effects of their best intentions and declare: incurable disease proven.

While the experience of psychosis is involuntary, hospitalization, forced medication, seclusion and restraint so often result in a sense of feeling punished. Too often the observable benefits of medication, which I do not argue need to be entirely disposed of, are heralded as the only hope for improvement, and treatment ends up being forceful in ways that can exacerbate trauma.

For some forced and in a state of emergency, clinical culture that records notes to justify payment may seems to resemble a U.S. prison with a diminished sense of justice and no sense of the potential for recovery. One of the reasons for the oppressive culture that develops is an odd sense that acknowledgement or inquiry about the world that exits in the rabbit hole will make community members worse. Thus, if one of those individuals receiving Special Messages starts to express themselves in ways others may not understand, they get halted. It might bring up trauma that these people cannot handle. Notes get written about that person’s ineffectual manner. They get repeatedly told about how to behave as though their true experiences have not valid meaning. They may be directed to focus on little kid things like hygiene in ways they stop listening to. Oddly, hygiene may get worse in rebellion.

I recall early in my career a woman staying at a crisis house I worked in saying, “Okay, it’s time to clean the cans!” Throughout the day she had made reference to cleaning the cans and I had no idea what she meant. And, then, as she dunked the brush into the commode she exclaimed in the most oppressed of manners, “when they tell you to clean the can, you clean them . . . clean the cans, clean the cans, clean the cans.” While at the time I think I managed to handle this in a way so that we both had a laugh, her point reverberates in my mind: why listen when your sense of rights and ownership in the poverty of your board and care home or single room occupancy hotel remains. Why do what you’re told, when you don’t get anything for it, not even a safe place to live with some young kid telling you what to do.

“Don’t go down their rabbit-hole,” is the best advice of the well-intentioned, best educated of our clinical experts.

“Establish a relationship by separating your understanding of reality from theirs,” is the pervading mentality by CBT for “psychosis” experts.

While this wisdom may be the best psychiatric folks can do because they don’t understand processes of “psychosis.” This work seeks to change this.

Excerpted and revised

May 22, 2016

Ways Good Research May Downplay Social Phenomena and Amplify Generalization:

Social Dynamics Neglected in the Treatment of “Psychosis”

If we were to measure the success of the field of psychology in terms of its ability to help people with “psychosis” and improve the conditions in which they live, many might conclude that there has been a covert dark process against the message culture in years since Freud. The World Health Organization has records that suggest that recovery is more common in third world countries than in the U.S. were there is so much money spent on treatments, yet so little treatment available to the many who need it. Still, our psychologist are are often taught more about psychoanalytic theory than about the culture of “psychosis.” Additionally, there is evidence that, just as philosopher Michel Foucault predicted that incidents of Madness are on the rise in the modern world. The idea that social discourse can exclude and eventually alienate a person to the point of madness is a powerful one.

Indeed I have heard stories of people who start out homeless or in isolation in prison become permanently in “psychosis.” I myself let the corruption inherent in the politics of section 8 housing projects drive me into madness because I failed to accept the black market dynamics that dominate in our power structures. Indeed not fitting into a social discourse can be very limiting.

A Movement Divided by Research Generalization:

It is hard to be involved with promoting recovery from “psychosis” these days without coming across people in the movement who are against medication. Robert Whitaker’s book, Anatomy of an Epidemic popularly blames the well documented rise of madness on the use of medication. While misuse of medication, along with the medical paradigm is clearly an epidemic that needs to be addressed, I don’t think that it alone is the cause of the rise of incidents of mental health issues in modern society.

Effective work with “psychosis” has been documented in research. There have been many self-directed, med free movements: moral treatment; psycho-social rehabilitation efforts at Sotoria House or I-ward; and the hospital-free houses initiated by Laing. So medication-free is possible for some!

Even though it is really bad that the mainstream AMA corruption and financial concerns block such efforts, I would like to argue that simply collecting research on their effectiveness does not capture the whole picture. There seems to be little thought given by research enthusiasts to realities of class or race-skimming in contrast to experiences of mass ghettoization that the majority of people who deal with “psychosis” must negotiate.

While med-free alternatives are certainly better than the hospital for many, I’d like to argue that recovery is more of a personal art than a scientific formula. Efforts that worked in the past generations, would need to factor in the immediate changes in culture and adjust to the region. Additionally, I would like to argue that with the level of homelessness and disparity in our current society, many of these efforts no longer exactly fit our needs.

I believe an anti-medication agenda, like Whitaker’s can happen when the focus of work is based on research. Just like the appalling pharmaceutical industry develops research by buying doctor’s documentation that simultaneously justifies their payment from insurance companies, med-free research fell short of proving that it worked for all individuals. Having some med-free alternatives makes sense for those who have been damaged by over-medication and for whom medication simply doesn’t work makes sense, but I’d argue that it is a generalization that everyone in society should take that direction.

The Reality of Mad Diversity

In short, psychological data can be used to make generalizations that can promote exclusion and alienation. This can divide the mad community. If Foucault is right and exclusion from discourse causes alienation that causes madness, requiring recovery figures to be medication free can hurt a lot of people who are stuck in perpetual traumatic circumstances. According to Whitaker’s research the haves will be bipolar and I have, at times, experienced feeling hated or dominated for daring to proclaim that I am self-proclaimed, have-not schizophrenia in survivor circles. I believe that message receivers need to learn not to generalize in treatment, that mad diversity can be learned. Sadly, mad people who are successful can easily promote their road to success with such passion, that they drown out other voices. Indeed the problem with the concept of relying on research to drive a problem-based mental health movement is that it leads inherently to generalization unless one can negotiate issues of culture effectively.

Socio-cultural Factors so Easily Missed by Mainstream Evidence-Based Practice

I believe that issues of social disparities, economic change, secret societies, corruption, the diminishing of spiritual insight, and other kinds of abuse play just as much a role in the phenomena as over-use of medication. If one is to examine my own personal story as laid out in my memoir, one might see how issues politics and corruption can play a role in mental subjugation and health issues. Even more powerful is my experience treating individuals in Oakland CA, some of whom are struggling to endure extreme states of deprivation, in terms of both basic needs and cultural capital. For many in urban board and care homes, medication is a non-issue, it is needed to endure. I have heard some real-life people in Oakland, claim to have endured more violence in street life than they did as soldiers in Viet Nam. And furthermore if one is to consider the work of Franz Fanon, just as a small example, one would see that I am not the only one who says social contexts matter. The early psychological anthropological of Nancy Scheper-Hughes looking at economics in Ireland also can work to reinforce such claims. Thus, all voices need to be lifted, not just that are disproportionately privileged.

And while it is a good thing evidence based practice efforts is now trying to bring about paradigm change to recovery, I see it merely a replication of an old, diseased process. As a result, I intend to look at the way psychological theory operates. I intend to look at the presumption that any theory universally can carry itself across cultural divides, epochs, and even locales. Perhaps mental health workers need to be more mindful of how universal theories get in the way of meeting a person where they are at. In the process I hope to point out the way “psychosis” has been woefully invisible in the process of theory. I think that concepts of universality of theory, mixed with social conflict and exploitation in “advanced” and powerful societies may have the effect of making things worse, not better, for the burgeoning lot of message receivers.

Excerpted Draft

May 14, 2016

Midwest Book Review: Small Press Bookwatch: May 2016: Reviewer’s Choice

http://www.midwestbookreview.com

Reviewer’s Choice

Fighting for Freedom in America

Clyde Dee

Outskirts Press, Inc.

10940 S. Parker Road, #515, Parker, CO 80134

http://www.outskirtspress.com

9781478759928, $20.95, PB, 328pp, http://www.amazon.com

Synopsis: When anonymous mental health worker Clyde Dee finds himself working in a Section 8 housing project that is notorious for drug dealing, he is mysteriously compelled to break the codes of standard drug war conduct. Uncanny threats and coincidences and desire for justice drive him to question the pillars of his profession and his own wellness until he decides to go off a low dose of anti-psychotic medication. Stopped by police in an effort to exit the country, Clyde is incarcerated in a State Hospital psychiatric ward for three months and then is released to the streets. Clyde’s story reveals both the innards of Schizophrenia and how a person can learn to make peace with the forces that are following them around. Clyde is able to overcome homelessness, under-employment, and harassment with family support and morph into someone who is fighting to gain attention for his successes in treating others who are in the throes of a “psychotic” episode.

Critique: An intensely personal and impressively well written memoir, “Fighting for Freedom in America: Memoir of a ‘Schizophrenia’ and Mainstream Cultural Delusions” is a compelling read from beginning to end. Very highly recommended for both community and academic library collections, it should be noted for personal reading lists that “Fighting for Freedom in America” is also available in a Kindle edition ($5.99).

May 1, 2016

Recreating Myself within a Changing Economy

Seventy years ago my family closed a lumber company in upstate New York. A series of small towns had built up primarily around the business and had to be abandoned and redefined. As is often the case, times change the economy and people have to find new ways to survive.

Though I never considered that the closure of the company had much of an effect on my family, as the first born in the second generation since the closing I carry a weight that I have not always understood. For years I have seen my father at times thanklessly function as the steward of swaths of land and vacation homes up in a small town within the region. I, on the other hand, have come to refuse to have any part of the life up there. I have rejected the wealth and privilege and significantly let the rest of the family down.

Usually one does not think of a child born with such immense privilege as ending up homeless and in a state mental hospital. At some points in my journey I have been defined by long lists of psychiatric diagnosis. I prefer to consider myself as having chosen to find a new way to survive based on a changing economy.

Emotional Angst:

The summer I was fifteen, I started the process of breaking away. I hadn’t slept more than two hours a night over the past six months.

About three months prior to a move to a custom-built, modern, plastic house that I objected to, the insomnia started. I somehow had the premonition that it was the end of our family and that I would be blamed. I could no longer stand to sleep on a bed. I almost always ended up wrestling on a mobile futon on the floor. Usually around four in the morning after I finally woke my mother up to receive support, I would get in the right spot—maybe with my feet on the futon and my head on the floor—and I would drift off, only to wake in two hours to the hustle and bustle of a day at private school where both my parents taught. At one point before the move, I reached such a state of angst alone in my room that I plunged a knife into my cheap foam mattress. I really did not understand the emotional dysregulation I was experiencing. I did some other bad things to express my angst. I meant business. I loved my family and did not want to break from our traditions.

Coming to Reject the Privilege of my Family:

By the time the summer rolled around, my father and I were driving the old Chevy Malibu up to the Adirondacks for a week on our own over the fourth of July. We stopped at a fast food restaurant and my father chided me about my work ethic. I had still managed to start on the varsity team as a second baseman and bring home mostly A’s in spite of an undiagnosed learning disability. Still, my father was critical about my slowness. “You just don’t seem to like working for works sake the way Grandma and Danny Dewey do,” he said. Though I was always busy on the weekends with yard jobs, not sleeping was slowing me down. The A’s I brought home never seemed to earn me any notice.

We were going up to clean up the Lodge from the Dewey’s our previous renters who were a welfare family. I had befriended the two boys that were close to my age and had never had friends so dear. When the younger of the two got five dollars for his birthday, seeing my depravation, he insisted on giving me candy. We had wild adventures, but those days were now over and they had to move on with an eviction on their record. Their older brother was already in jail for holding up a store to help the family survive. For my birthday I had received a hammer that my father had purchased for the elder, Danny. “I wanted to give the hammer to Danny and say, hey kid, you’re a great worker; but his mother owed me so much money, I just couldn’t do it.”

I was hurt that my father felt I wasn’t a good worker and decided right then and there that I would not slow my father down on this work trip. I would do whatever it takes to satisfy him. And for that week I slept after 12-16 hour workdays. Though I cannot remember everything that we accomplished, we were putting up our large building up for sale on the market and there was a lot of mouse shit mixed in with the process. On the ride home though I agreed that the week was productive, I was somehow was not very happy about it. It was the best I could do to express to him the way I felt. I did not have the Dewey’s as friends anymore. When I got home the sleeplessness returned

Recreating Myself:

My sleep problem ended later that month when my father paid for me to an Outward Bound Program. We had so many slow hikers in our group; we often had to hike into midnight to get ourselves back to base camp. Sometimes there wasn’t enough food to eat because others didn’t share. Most of the kids were spoiled, suicidal, and missed their recreational drugs. But when I saved their lazy asses, they were actually grateful for my intervention and the usual taunting stopped. We ran a half marathon at the end. It was truly a glorious and amazing experience!

When I returned home my father said, “I can see that you have really grown during the program, I can see you better asserting your needs. But now that you’re back in the family I can see that the gains you made are going away.” My father’s negative forecasts about me always had a way of coming true. I figured that that was what he needed from me at the time, so I stopped being assertive. I did not realize that I could escape from the family traditions.

Psychiatric Strife Away from the Family

I was right about my family collapsing, it happened the following winter. And although, I was as distressed about it as I was about the move; and about the fact that my Dad simultaneously stopped his career in school administration, I maintained my work habits. I also took the blame for all the pain in the family. As my peers and my mother began engaging in drinking and partying, I soon became anorexic to cope with my strong emotions and my ongoing sense of being excluded and bullied. Then, after a long hospitalization I was placed in a temporary living situation away from my parents, hospitalized again until I met an older woman with whom I moved into the ghetto with to attend a commuter college.

My next diagnosis when I came in off the streets where I worked in a ghetto Deli with slicked back hair and an urban drawl was: schizotypal personality disorder. I think the psychologists who evaluated me presumed the school I attended was a school for losers and they had no idea how seriously I took my studies.

Then more diagnoses were added, ADD and Dyslexia, when I stubbornly persevered in spite of being urged to go on disability and put myself through a Master’s Program working full time.

In my career, I became very engaged with people off the streets with Schizophrenia and when I moved out west and engaged in setting up services in public housing circumstances. My advocacy and political maneuvering cause me to have a lot of success and power in the community. Thus, when I squealed to the paper, I faced months of threats until I got scared and caught a two and a half year schizophrenia.

During the time period I was in severe “psychosis,” I never worked harder maintaining minimum wage employment while believing I was being monitored by the government. With my father’s help I avoided homelessness, shelters and institutions. After I got better and started to make a living wage, the diagnosis changed to schizoaffective and now that the DSM V is out I’ve had some doctors argue that I am bipolar. All of these diagnoses have become ridiculous concepts to me. But to overcome them, I have had to overcome the negative forecasts of my father, the psychologists in the hospitals, and those exacerbated by the covert corners of our government. I have had to learn a lot to recreate myself as a man without property.

Celebrating our Survival

Now that I have been embedded into a responsible job for the past fifteen years where I work in ghetto contexts and have written a memoir detailing my experience with “schizophrenia,” I am participating in planning a reunion for my Dad up in the land I have fought so hard to escape from. Now with the rest of my family, I will have to speak to honor my father’s work as a steward. I will think of all the friends I have made like the Dewey’s over the years: from the ghetto deli, to the project housing, to the deprived board and care homes peppered throughout the Richmond ghetto. I am fighting now to pave the way opportunities for people who have been through “psychosis” to recover and work to help others who are suffering to recreate themselves. I know it can be done if we halt the institutionalization and change the medical model paradigm.

I really am ready to celebrate my father’s life and his work. I now can see that when I was fifteen, my father gave me what I needed to survive on my own outside our privilege. Now I can see that he spent his life paving the way for my escape and ability to recreate myself in the economy. I know that inside he has despised his privilege and the damage it did in the past much as I do.

Now I work to maintain the privilege to live outside of the concentration camp barracks that so many others who have had to recreate themselves end up being enslaved to. Now I can see that for the most part my father fought hard so that I may be free. As times are changing and the disparities in this country are becoming more extreme, more and more people are being displaced by an economy that functions for the few, psychiatric diagnosis will be on the rise for many of the others of us who want to break away and escape from the injustice of slavery and genocide that shames our past. My prayers go out to those who break away and recreate themselves. We all can survive! And I still maintain that, though I have been wrong at times, I do not deserve or want the massive privilege I was born into. I have fought hard for that freedom. My Dad let me have it.

April 24, 2016

Speaking at the Spring CASRA Conference 2016, May 4 at Concord Hilton

2016springconferencebrochureearlyregistration4.12.16

Mad Diversity: Healing through Telling the Stories

Tim Dreby, MFT, Rehabilitation Counselor, Alameda County Behavioral Health Care Services

Redefining “psychosis” in group therapy has led to a cultural exploration of what it means to be mad. Learn how the telling of silenced stories can help unite mad people from diverse experiences and backgrounds. Participants will learn about eight healing strategies used in groups to help individuals to find meaning and to enhance their level of social rehabilitation.

Hope to sell book at a discount while there