K. Lee Lerner's Blog, page 5

March 22, 2022

Russian propaganda and western media cheerleading mask causes, perils, and probable outcomes in Ukraine

March 22, 2022

Russian media is a tightly controlled instrument of state propaganda. Sadly, large segments of our western media are now independently engaged in cheerleading that often crossed into propaganda.

The Ten Essential Techniques and Elements of Propaganda. Go ahead… test it against all sides in all wars. Although formulated for war, with some minor modifications the list is also applicable to political and culture war propaganda.

“1. We don’t want war; we are only defending ourselves.

2. Our adversary is solely responsible for this war.

3. Our adversary’s leader is inherently evil and resembles the devil.

4. We are defending a noble cause, not our particular interests.

5. The enemy is purposefully committing atrocities; if we are making mistakes this happens without intention.

6. The enemy makes use of illegal weapons.

7. We suffer few losses, the enemy’s losses are considerable.

8. Recognized intellectuals and artists support our cause.

9. Our cause is sacred.

10. Whoever cases doubt on our propaganda helps the enemy and is a traitor.”

–Historian Anne Morelli’s summary* of Arthur Ponsonby’s 1928 classic on war propaganda, ‘Falsehood in Wartime,’ as contained in Morelli’s monograph ‘Principes élémentaires de propagande de guerre’ published in 2001.

The Ukrainians have put up the unbelievably brave resistance to a Russian invasion driven by false narratives, but the Russians are winning, slowly grinding the Ukrainians down. Without more direct intervention on behalf of Ukraine, I fear the inevitable remains just a matter of time.

Dangers of escalation, including use of tactical nuclear weapons and of radiologic incidents resulting from accidents, collateral damage, and sabotage have also increased.

Despite a heroic Ukrainian resistance, almost a month after the Russian invasion, I see nothing that yet changes my initial assessment that, at best, a rump Ukraine, possibly isolated from the sea, will be forced to capitulate to the essential demands Russia set forth before their invasion regarding the independence of the separatist Eastern provinces, the annexation of Crimea, and a pledge of neutrality / abandonment of pursuit of NATO membership.

==========

[*] As originally published in French:.

1 Nous ne voulons pas la guerre

2 Le camp adverse est le seul responsable de la guerre

3 Le chef du camp adverse a le visage du diable (ou « l’affreux de service »)

4 C’est une cause noble que nous défendons et non des intérêts particuliers

5 L’ennemi provoque sciemment des atrocités, et si nous commettons des bavures c’est involontairement

6 L’ennemi utilise des armes non autorisées

7 Nous subissons très peu de pertes, les pertes de l’ennemi sont énormes

8 Les artistes et intellectuels soutiennent notre cause

9 Notre cause a un caractère sacré

10 Ceux (et celles) qui mettent en doute notre propagande sont des traîtres

Photo: Vicksburg National Military Park, VIcksburg Mississippi. Photo and content by K. Lee Lerner. CC BY-NC-ND

Taking Bearings: Russian propaganda and western media cheerleading mask causes, perils, and probable outcomes in Ukraine

March 22, 2022

Russian media is a tightly controlled instrument of state propaganda. Sadly, large segments of our western media are now independently engaged in cheerleading that often crossed into propaganda.

The Ten Essential Techniques and Elements of Propaganda. Go ahead… test it against all sides in all wars. Although formulated for war, with some minor modifications the list is also applicable to political and culture war propaganda.

“1. We don’t want war; we are only defending ourselves.

2. Our adversary is solely responsible for this war.

3. Our adversary’s leader is inherently evil and resembles the devil.

4. We are defending a noble cause, not our particular interests.

5. The enemy is purposefully committing atrocities; if we are making mistakes this happens without intention.

6. The enemy makes use of illegal weapons.

7. We suffer few losses, the enemy’s losses are considerable.

8. Recognized intellectuals and artists support our cause.

9. Our cause is sacred.

10. Whoever cases doubt on our propaganda helps the enemy and is a traitor.”

–Historian Anne Morelli’s summary* of Arthur Ponsonby’s 1928 classic on war propaganda, ‘Falsehood in Wartime,’ as contained in Morelli’s monograph ‘Principes élémentaires de propagande de guerre’ published in 2001.

The Ukrainians have put up the unbelievably brave resistance to a Russian invasion driven by false narratives, but the Russians are winning, slowly grinding the Ukrainians down. Without more direct intervention on behalf of Ukraine, I fear the inevitable remains just a matter of time.

Dangers of escalation, including use of tactical nuclear weapons and of radiologic incidents resulting from accidents, collateral damage, and sabotage have also increased.

Despite a heroic Ukrainian resistance, almost a month after the Russian invasion, I see nothing that yet changes my initial assessment that, at best, a rump Ukraine, possibly isolated from the sea, will be forced to capitulate to the essential demands Russia set forth before their invasion regarding the independence of the separatist Eastern provinces, the annexation of Crimea, and a pledge of neutrality / abandonment of pursuit of NATO membership.

==========

[*] As originally published in French:.

1 Nous ne voulons pas la guerre

2 Le camp adverse est le seul responsable de la guerre

3 Le chef du camp adverse a le visage du diable (ou « l’affreux de service »)

4 C’est une cause noble que nous défendons et non des intérêts particuliers

5 L’ennemi provoque sciemment des atrocités, et si nous commettons des bavures c’est involontairement

6 L’ennemi utilise des armes non autorisées

7 Nous subissons très peu de pertes, les pertes de l’ennemi sont énormes

8 Les artistes et intellectuels soutiennent notre cause

9 Notre cause a un caractère sacré

10 Ceux (et celles) qui mettent en doute notre propagande sont des traîtres

Photo: Vicksburg National Military Park, VIcksburg Mississippi. Photo and content by K. Lee Lerner. CC BY-NC-ND

The Ten Essential Techniques and Elements of Propaganda. The Russian Invasion of Ukraine: Russia Propaganda and Western Media Cheerleading Mask Causes, Perils, and Probable Outomes.

March 9, 2022

Taking Bearings: Iran’s nuclear breakout window narrows

March 9, 2022

Based on a recent International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Iran Verification and Monitoring Report of March 3, 2022 [1], and subsequent Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) analysis [2], Iran is continuing to advance its nuclear capabilities, hide nuclear research facilities, and thwart international inspections.

Here are ten things you need to know about the nuclear capacity of the Islamic Republic of Iran in order to offer cogent analysis of Iran’s compliance with the existing Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and/or ongoing negotiations by the U.S. to adapt that agreement before joining it once again as a participating party.

It takes about 25 kg of weapons-grade uranium (generally uranium enriched to contain 90 percent U-235, the fissile isotope) to make an atomic bomb.Iran has already accumulated uranium hexafluoride (UF6) –as of 19 February 2022 at least 49.1 kg of UF6 containing 33.2 kg of 60 percent enriched uranium and some 20 percent enriched uranium) that it can quickly feed into centrifuge cascades to produce weapons-grade uranium. Iran has estimated total stockpile of just over 180 kg of 20 percent enriched uranium in UF6 and other chemical forms

With 33.2 kg of 60 percent enriched uranium and its known/declared centrifuge capacity, Iran could produce enough weapons-grade uranium for one atomic weapon within a period estimated to as fast as two to three weeks. Within three to six weeks Iran could produce enough weapons-grade uranium to fuel two bombs.

Although previous Iranian efforts to produce an atomic weapon (e.g., the Amad plan led by Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, see footnote [3] below) focused on the use of weapons-grade uranium, Iran’s concealment of its prior programs, facilities, and hindrance of inspections leaves open the possibility that it may have explored the development of cruder weapons capable of using 60 percent enriched uranium. Iran needs only an additional 8 kg of 60 percent enriched uranium (HEU) to make a crude nuclear weapon not requiring additional centrifuge passes. ISIS estimates that Iran could produce 54 kg of HEU annually. At Iran’s current pace, it will have sufficient HEU to make a crude bomb by summer (2022).

Prior declarations and inspections show an ongoing effort by Iran, including multi-step enrichment experiments – to upgrade its uranium enhancement capacity.

Iran’s stockpiling of enriched uranium, including the production of near 5 percent and 2 percent enriched uranium, has accelerated. Since the last IAEA report. Iran’s 20 percent enriched uranium stock increased by from 113.8 kg to 182.1 kg, and the near 60 percent enriched uranium (HEU) stock increased by 15.5 kg to 33.2 kg.

Since February 2021, Iran has denied the IAEA the ability to inspect and/or monitor known/declared Iranian nuclear research facilities (including Esfahan or Karaj sites). Gaps also exist in both monitoring and Iran’s accounting for the number and use of centrifuges at other facilities including the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant and Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant

According to ISIS, “the IAEA also reports that it cannot verify Iran’s JCPOA commitments related to prohibited nuclear weapons development activities.”

Although Iran has sent 23.3 kg of it HEU to its Fuel Plate Fabrication Plant (FPFP) in Isfahan, according to ISIS, “it is expected that only a tiny fraction will be converted into targets. As such, the production of targets will not remove the proliferation and breakout risks posed by Iran’s stockpile of HEU. This step should be viewed as a cynical attempt by Iran to place a civilian mask on an inherently military material and lay a precedent for future production of HEU.”

As it had warned in December 2021, in early February 2021, Iran began producing uranium metal (see background information below) from both 20 percent enriched uranium and 60 percent enriched uranium for by the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). This an open violation of its JCPOA commitments. In an article published in Science on 15 July 2021 (“Iran’s plans for research reactor fuel imperil revival of nuclear deal”), Andrea Stricker, a nonproliferation analyst at the nonprofit Foundation for Defense of Democracies countered Iran’s claim that it was using the metal to produce medical isotopes. “Iran is pursuing a strategy of brinkmanship,” said Stricker, “It is using civil-use justifications as a pretext to brazenly advance its nuclear weapons–related knowledge.”

===========

[1] https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files…

[2] https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/det…

[3] Despite continual Iranian denials that it ever pursued nuclear weapons, in a 2015 report by the IAEA titled “Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme,” IAEA scientists concluded that “a range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device were conducted in Iran prior to the end of 2003 as a coordinated effort, and some activities took place after 2003…”

===========

Background for non-scientists

Uranium, atomic number 92 on the Periodic Table is the heaviest naturally occurring element on Earth. The uranium nucleus contains 92 protons but a variable number of neutrons to create uranium-238, uranium-235, and uranium-234 isotopes of uranium. About 0.72 percent of natural uranium is U-235 All uranium isotope are radioactive as they decay, but only U-235 is capable of fission (a spitting of the nucleus) when it absorbs a neutron. This splitting releases tremendous energy

Uranium ore treated to form uranium oxide (“yellowcake”) and then combined over a series of steps with anhydrous hydrogen fluoride and fluorine gas to form uranium hexafluoride (UF6). Uranium hexafluoride can exist as a gas used in further enhancement or as a liquid or solid for storage and shipping. Uranium hexafluoride does not react with atmospheric gases (oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, etc.) but is reacts with water and water vapor in the air to form hydrogen fluoride (a corrosive) and uranyl fluoride (UO2F2).

During gaseous diffusion, uranium hexafluoride (UF6) gas passes through hundreds of fine porous filters that help separate the faster moving U-234 and U-235 atoms from the heavier and slower moving U-238 isotopes. Accordingly, two output streams — one enriched in U-235 and the other depleted in U-235 are observed. With further processing of the enriched uranium the percentage of U-235 increases.

To be used as nuclear fuel the uranium must be enriched 3 to 5 percent. Highly Enriched Uranium is 60 percent U-235 and weapons grade-uranium is 90-plus percent U-235

Centrifuges produce a force much stronger than the normal gravitational force. The spinning of gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) creates a sight separation of heavier U-238 and relatively lighter U-235 atoms. By drawing off the U-235 enriched region and repeating the process thousands of times through a chain or cascade of high-speed centrifuges that spin about 100,000 rpm, one obtains increasing purified or enhanced U-235. Adding calcium to the enriched U-235 creates a salt and a pure uranium metal for fuel rods or if enriched to weapons grade U-235, nuclear weapons.

Iran’s nuclear breakout window narrows

February 11, 2022

Warning!!! Boomer Alert!!!

January 22, 2022

Navy T-28 Engine Failure: Life lessons linger 40 years after

Scattershooting while wondering how quickly 40 years can pass…

“One of the finest displays of cool professional airmanship under pressure…”

— Vice Admiral W.L. McDonald.

When I was young, I always wanted to fly and to be a fighter pilot. That urge to fly was suppressed until I was accepted for Navy flight training in 1981. I interrupted my academic studies to attend and graduate from Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS, Class 2381) at NAS Pensacola with academic distinction. I received a Presidential commission to serve as a line officer in the U.S. Navy on September 11, 1981.

In addition to an array of leadership and soldering skills acquired at multiple DOD schools, serving as an officer and naval aviator also helped reinforce and refocus my early training in physics into practical applications related to aerospace engineering and its foundational fields of structural, mechanical, electrical, and computer engineering.

After commissioning, I attended primary flight school at NAS Corpus Christi, and then advanced jet fighter/strike school at NAS Kingsville, Texas. In flight school, I was named to the Commodore’s List for “academic and flight excellence.”

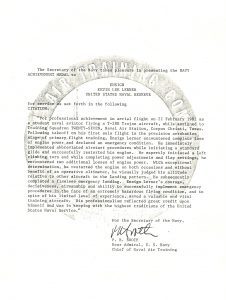

While still a student naval aviator, I was awarded the Navy Achievement Medal after managing an engine failure on takeoff and returning the field for a dead stick landing.

It was literally a life-defining moment.

In primary flight training at NAS Corpus Christi, I flew an old WWII style T-28. The T-28 was a massively overpowered trainer (especially compared to more contemporary military training aircraft) that offered steep learning curve to generations to new Navy flight students. On the road to flying a Tomcat, it was a necessary but difficult plane to master. I volunteered to fly it because I wanted the challenge and because the only squadron (VT-27) still flying the plane was located in Texas.

On just my second solo flight (PA2) – a flight to practice basic aerobatic maneuvers like loops, wingovers, and aileron rolls — I had a complete engine at 700 feet as I attempted to stay below landing pattern altitude until I could clear the base and climb out over the Laguna Madre. When the engine died, I immediately put the plane into optimal glide configuration and turned away from the base toward the water. As I tried to restart the engine, I also prepared to ditch the plane.

While flashbacks of Dilbert Dunker training during AOCS flashed in my brain, I went through emergency NATOPS restart procedures. Nothing worked until, at 200 feet, I tried the one shortcut procedure discussed by my instructors not in the NATOPS flight manual . By holding prime button, I dumped raw fuel into the carburetor and the engine caught. Holding the button, I continued to climb as turned back toward the base toward at a point called ”low key” where I could thereafter shoot a power off dead stick emergency landing.

This tale also includes my student-like slavish devotion to procedures that forced me to take my finger off the fuel prime button in order to key my microphone to make emergency radio calls (an action resulted in two additional power failures on my way back the base), a broken altimeter, and being shot at with a flare gun by the Runway Duty Officer (RDO) while I held off dropping the landing gear so that I could glide to the field.

This tale would, however, be incomplete without some humor at my expense. I had obviously not yet mastered a seasoned fighter pilot’s “Yeagerisms” and demeanor, and so the control tower tapes of the accident revealed an increasingly higher-pitched urgency in my voice during those aforementioned radio calls that became fodder for subsequent squadron ready room fun. It was many months before I regained a reputation for steely Yeager-esque resolve during night O-nav flights (attack training flights at high speed and low radar-avoiding altitudes (e.g., 200 to 500 feet AGL ) using structures and visual landmarks for navigation). I learned there were few things more satisfying that simply saying “Roger that” when asked to do outrageous things with a plane.

More seriously, however, what I learned of lasting value was command presence, and need to not to show fear or urgency even in crisis. I learned that — especially in times of chaos and crisis — keeping a quiet presence calms other, and that a quiet mind enhances problem solving.

For “professional achievement in aerial flight,” I was awarded the Navy Achievement Medal (see below) for “courage, decisiveness, and airmanship,”

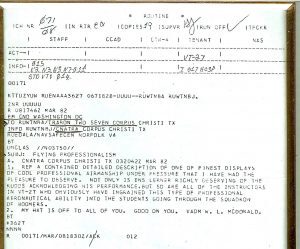

Far better than the medal, however, was a short communiqué from Vice Admiral W.L. McDonald to my squadron commander. Admiral McDonald graduated in the Naval Academy class with Wally Schirra (one of the Mercury 7 original astronauts. Flying an A-4, he led the first air strike against North Vietnam following the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

McDonald wrote that my handling of the affair was “one of the finest displays of cool professional airmanship under pressure that I have had the pleasure to observe.”

Admiral McDonald would go on to serve as commander of Operation Urgent Fury.

A copy of Admiral McDonald’s communiqué remains one of my prized possessions.

The there is still, however, a more humor to be milked from this incident.

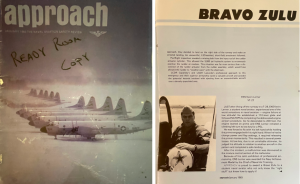

I was also given a “Bravo Zulu” in the January 1983 issue of Approach, the Navy flight magazine.

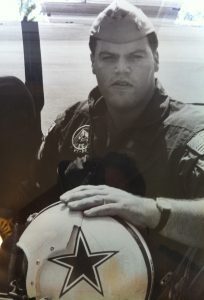

Months passed, however, between the time I raced from jet training at NAS Kingsville back to NAS Corpus Christi to have my photo taken in a T-28 cockpit and the time the photo appeared in print. The delay was a result of the Navy photo lab having to airbrush a sleeve on my bare left arm.

This was, remember, long before photoshop and I had originally posed for my photo with my sleeves rolled up. This was very fighter pilot-esque, but not pleasing to the Navy Safety Office.

The photo gaffe became emblematic of two personal maxims I hold dear:

(1) If you want to lead a life devoted to a general disdain of rules and guidelines — and even occasionally indulge in flagrant violation of said rules and guidelines (especially as an operational necessity) — one must perform at a high level when the chips are down in times of real crisis, and

(2) it is usually better to ask for forgiveness than permission.

I still love to fly. Whenever possible, especially at outlying fields, I use the military 180 “numbers for the break ” and still practice a carrier approach pattern for landing. I love practicing emergency landings, and I will do aerobatic maneuvers whenever allowed by the type plane I am flying. I invested years in preparing to fly a vintage WWII Spitfire in England, and I love taking young naval flight students for introductory rides to share a bit of language and “attention to detail” culture.