Ilsa J. Bick's Blog, page 30

January 20, 2013

Facial Recognition

As you recall, two weeks ago I posted about an upcoming book whose cover seemed to take its cue from the ASHES series. This week, I’d intended to follow up with more examples of just how important a distinctive look is for any series author and talk, in very general terms, about branding, the importance of both establishing a series “look” as well as cueing readers to the genre in which a book falls–because we all know this, right? That covers follow genre conventions? Yes? Anyway, I had all these great covers for Lee Child’s Reacher series lined up–but then, Kristine Kathryn Rusch beat me to it. As always, her entire entry is worth reading; she covers not only this topic but the Patricia Cornwall court case; stats on kids’ reading habits (good news for both ebook and print devotees, and to which from my n of two kids, I can personally attest is absolutely true); and–one more time–the importance of sustained and determined effort to writerly success.

Kris’s comments and examples of branding follow her discussion of the Cornwall case, and to be honest . . . I really don’t have much to add. Clearly, her comments have more valence for those writers who are putting their own work out there, but I’ve certainly noticed how much the various overseas ASHES covers, which I posted about here, play into both a) prevalent trends in YA lit and b) romance conventions. Neither observation is surprising given that many YA readers are female. Anyway, the point is that if you’re going to put our your own stuff, creating a distinctive style–a cover signature as it were–while also cuing potential readers as to genre expectations will not only help your fans find you but also alert new readers about what to expect when they crack open or download that book. (Oh, and her point about the importance of interior design? Also worth reflection: I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve actually tried to read a particular book I would really LIKE to like–no, I won’t tell you which one–only to give up because the interior design makes the bloody thing unreadable. So not only will I probably never read it, I won’t recommend the book to anyone either.)

Anyway, like I said, hop on by Kris’s site; read what she has to say. All true, and if I were putting out my own books at the moment, I would seriously consider signing up for that online design course both she and her husband, Dean Wesley Smith, offer. Guys, you could do way, way worse. These people know their stuff.

January 6, 2013

The Sincerest Form of Flattery

Okay, first up, before I forget: did everyone have a nice holiday? See all the relatives? Get rested up to start another year (which, for some of us, seems to be an artificial distinction because the day after is/was the same as the day before)?

Good. Now, roll up those sleeves and let’s talk turkey.

I’m unsure how this came to my attention, although I believe it was Twitter, but this past week, a friend–my publisher, in fact–posted the cover of an upcoming YA. NBD, so far; people are throwing up covers for new releases all the time.

Except . . . the reason this particular book snagged my friend’s attention wasn’t for the content but the look.

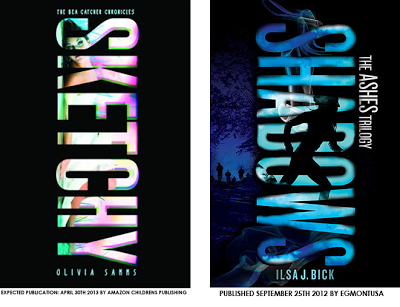

Freaky, right? And notice who’s putting the book out there: Amazon Children’s Publishing. Which means that whoever designed the cover for the book had a lot of covers to look to and choose from for inspiration.

If you think this made more than a few fans unhappy or weirded out or mystified . . . you’d be right. Some wondered what I could actually do about this–the quick and dirty answer is a whole lot of nothing because there’s nothing to be done–and that made me feel good, to tell you the truth. It’s not often that fans get irate on your behalf.

Yet if you think this is some kind of violation of cover copyright . . . you’d be wrong. Because we all know copyright law as it pertains to using images, correct? If you need a quick refresher, try this article and this one. Right off the bat, I can tell you that this is not a violation of copyright in the slightest. Granted, I don’t own the copyright for my book covers; my publisher does (or the artist hired by my publisher). If this constituted a copyright violation, then so would every book cover featuring, say, a silhouetted figure running across a landscape (I’ll bet I saw two or three YAs with that cover last year) or a shot of a forest or a cityscape or girl/guy in profile . . . You get my drift.

If the cover on the left does anything at all–under copyright law, that is–then it comes closest to paying “homage” (and I use that loosely), and then just barely. Really, all that’s been “copied” is the positioning of the title. Is it close enough to provoke a second glance? Sure. Is it a violation of copyright? No.

But here’s an intriguing question–to me, at least: what, exactly, is the cover on the left supposed to convey? We judge books by their covers all the time. In an earlier post, I talked about the reason the ASHES series changed; even though I adored the original hardcover, the book itself didn’t pop off the shelf. It tended to get lost. So the cover had to change because the whole point of the cover is to induce you to pick up the book and start paging through.

To my eyes, the new ASHES look–and more specifically, SHADOWS–evokes menace and ambiguity. You’re supposed to wonder: who’s running, and from what? Who are those people in the background? Are they even people? Are they something else? Shadows, at night and in the woods, are slate and purple and silver and blue, and of course, the thematic motif of smoke references the post-apocalyptic. It’s a lovely cover, and suggests precisely what you might find inside.

SKETCHY’s cover is . . . well . . . interesting. What does sketchy mean, anyway? Here’s what Wiktionary has to say about the word as it pertains to a person:

(slang, of a person) Suspected of taking part in illicit or dishonorable dealings.

Because he is so sketchy, I always think that he is up to something.

(slang, of a person) Disturbing or unnerving, often in such a way that others may suspect them of intending physical or sexual harm or harassment.

Jack is so sketchy, I think he’s stalking me.

With that in mind, let’s look at the cover again. There’s a girl there, right? Lying on what looks like a bed? Covered with a sheet (so you know she’s probably naked)? Only the image is partially obscured by the title itself; you really have to work to see this girl–which is precisely what I think this cover wants you to do. It wants you to want to see her and, by extension, figure her out. All that plays into the slightly dangerous, slightly come-hither, slightly illicit and sketchy story this cover promises.

So does the cover do its job? Yes, it does. If–and this is a big if–the person responsible for the cover took SHADOWS as a jumping-off point, then he or she might have wanted to capture some of that cover’s disturbing and unnerving elements. In that way, SHADOWS served to inspire. Of all the cover designs out there, that graphic artist chose SHADOWS to get his/her point across. In the end, what I take away from this is the truth of that old saw: imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. I don’t think there’s any way that anyone will get the two books confused.

Besides . . . we all know which book came first.

December 9, 2012

People Like Us

A couple years ago, some writer-friends and I were having this discussion about Obama and that brouhaha about Reverend Jeremiah Wright’s remarks about Jews and the like with another, much more seasoned pro writer-friend. I don’t even remember what the specific comments were, but I do recall my pro-friend turning to me and saying something like, “Listen, white girl, you just don’t know.” Now, I didn’t take offense or anything because my friend’s comment wasn’t meant as a slap. My friend was making a point that I, as a white girl (even a Jewish white girl, at whom some of these remarks were broadly directed), couldn’t really grasp the cultural milieu in which the comments were made.

I believe my friend–to a point. It’s true that this friend is much more knowledgeable about black history; in fact, this friend wrote a very fine mystery series that featured a black protagonist. While the specifics of the series aren’t important, this is: at the time these books were out and about in the world, my friend wasn’t touring or publicizing them much for a very simply reason.

My friend is white. And of the opposite sex from the protag.

Talk about irony and (a bit of) reverse discrimination.

Why am I not more specific here? Honestly, I’m not trying to be a tease, but my point isn’t to out my friend. But I was reminded of this incident after reading the New York Times piece earlier this week all about young Latino readers and educators’ fears that these younger kids might not be as drawn into reading because there’s a dearth of Latino protagonists for them to identify with. Read the comments, and you’ll find both an even split and a wide array of responses. Some people think this is a big deal; others don’t.

Now I’ll be really honest here: by and large, my feeling is that this is another of those New York Times hand-wringing non-issues. You could say that I think it’s not, because as a white girl, I was in the majority back in the day and so always felt that I was being represented in one way or another in whatever I read–but you would be wrong. There really weren’t that many female protagonists out there for me to identify with. In fact, in a large proportion of both classical and contemporary lit, the protags were/are white males–and I can guarantee you that the overwhelming majority weren’t Jewish.

You want to read about diversity? Pick up any good sf with alien species as the primary protags–I remember one book that featured these funky insect-like creatures–and then tell me that I couldn’t possibly have enjoyed that because, oh, the protagonists don’t look like me. Back when I was a kid, there wasn’t anyone out there in either literature or film for me to take as a role model–and so what? I’ve never looked to books for role models, nor do I, as a writer, think about providing a role model for my readers. That’s way too preachy for me. Conversely, I don’t remember a single book that was just so influential I carried it around like a talisman or modeled my life after it. I wanted role models? They were called parents and teachers and other significant adults. ((I mean, my God, my mom was working outside the house, doing science stuff and going for a PhD in an era when women just didn’t do that. And who were her role models? Her father was a sponge diver and then worked in a rubber factory; her mother was a housewife. Neither went to college; I doubt my grandmother made it out of high school; they lived in a crummy section of Akron. But they all worked hard.) Similarly, none of my role models lived in books.

I’ll be honest (again): whenever I was handed the rare book with a Jewish protag (always male, as far as I can recall), I remember cringing. Reading stories about people I knew–folks I saw every bloody day–didn’t interest me in the slightest. Revisiting certain events in my cultural past–say, the Holocaust–was and remains a busman’s holiday. Then as now, I look to books to tell me a good story.

I may be really off-base here; maybe I just don’t get it. But when I’m immersed in a story, I couldn’t care less what the characters look like, or about ethnicity. (Oh all right, yes: if this is a romance that keeps mentioning that the girl is a size 2 and wears strappy sandals without breaking an ankle . . . yeah, okay, I may not want to step on the scale for a couple days, but I don’t stop reading on that basis.) When the story revolves around the character’s difference–Invisible Man and Native Son spring to mind–then, yes, of course this becomes an issue, because the difference is the story. But that difference doesn’t keep me from being able to either get into the story or feel along/identify with the characters either.

The magical thing about becoming lost in a book is that you also lose sight of who you are along the way. It’s really quite an interesting phenomenon, if you stop to think about it. You can both read yourself into a character and stand alongside at the same time. You get wrapped up in the adventure at the same moment that you may be thinking, Oh no, don’t do it! You can get mad at a character for being so stupid and still get a vicarious thrill with that first kiss. All of that speaks to the skill of the story-teller and–to my mind–has virtually nothing to do with what the characters look like, or whether they’re like me. (I mean, guys, think about it: are we really saying that kids can’t possibly identify with Wilbur because he’s a pig, and they’re not? That I can’t read about or enjoy or even identify with characters like Fiver and Bigwig in Watership Down . . . because I’m not a male rabbit? Get real.) Picking up a book is a way to get away from me now, just as it was a means to take me on an adventure and out of myself back then. The business of a book is not to instruct.

Which brings me back to my very talented pro-friend, who could fashion a thoroughly wonderful series about a character of a different gender, culture, and ethnicity, not because my friend was the same but because that writer was (and is) empathetic, passionate . . . and a damned good writer.

Now that’s what I call a role model.

November 25, 2012

For Any Soldier

This post has nothing to do with writing.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

On Thanksgiving Day, I happened across this picture:

And–for some bizarre reason–I was both moved and a little angry. Being choked up . . . I understand that. I always get emotional when I think about soldiers doing what they’ve volunteered to do. But it was the “enduring American attitude” thing that made me pause.

Sometimes, when I spot pictures like this or those little magnets people put on their cars–you know the ones I’m talking, those yellow or red-white-and-blue ribbons that say SUPPORT OUR TROOPS–I get a little impatient. (To be fair, I become equally impatient whenever I hear anyone refer to a soldier–or any person in any kind of uniform–as a “hero.” The word is so overused these days as to become virtually meaningless.) A trendy magnet is nice, but it really requires almost no thought, and–honestly–is worth only a few pennies of support, if that.

Worse, something like a magnet fosters the illusion that we are somehow on the same footing and have some idea what our troops have to put up with when we really haven’t a clue. Yes, I was in the military; yes, I served during Desert Storm, but I was never deployed. All the casualties I saw were those med-evaced stateside. I don’t know what it’s like to be far away from home and stuck in a place where a) people are trying to kill you; b) you don’t get hot meals; c) people are trying to kill you; d) a shower is a luxury; e) people are trying to kill you; f) your convoy’s been blown to pieces or someone just stepped on an IED, and that soft, sloppy wet thing you just stepped in used to be inside a person; g) people are trying to kill you; h) sometimes you don’t sleep for days, or–sometimes–all you do is sleep because there’s absolutely nothing else to do and you’re so bored you wish someone would start shooting; i) people are trying to kill you; j) you worry what the heck you’ll be fit for when you do get out, if you’ll be able to find a job, and how you can possibly translate your proficiency at killing into something remotely marketable; and k) people are still trying to kill you pretty much 24/7. Yeah, okay, you volunteered; no one made you enlist. No one forced me to join up.

But here’s a stunner for you: in a country of nearly 313 million, a little under 1.5 million Americans are on active or reserve status. Do the math, and you find that number translates to a whopping 1% of the population. That’s astonishing, that we allow so few to bear all the risk.

And we have the gall to say we “support” the troops? What are we truly saying? Really . . . what does “support” mean? Has the word merely become a synonym for approve? Or I’m not against the military? It shouldn’t. ”Support” has a very specific meaning. To support someone is to bear his weight; to keep her from sinking or stumbling or falling. To support is to become the bedrock upon which a structure may rest. To support is to prop up and aid. To support is to be active.

So, get active. Spend a half hour on a web search, and you’ll find there are any number of organizations, such as AnySoldier.com, the Wounded Warrior Project, and Soldier’s Angels, ready and willing to help you locate active duty troops, the severely wounded, and military families in need. It’s not all candy and baby wipes either; many troops have zero access to even a small post exchange and a ton of folks at forward operating bases have nothing other than a microwave. These people need equipment, food, backpacks, magazines, toiletries. Some even ask for dog food to feed the strays they adopt (but, sshh, don’t tell anyone; animals are against regs).

A magnet is not support. Neither is a picture or an American flag. A moment of silence–of merely thinking about troops far from home–doesn’t cut it either.

This year, get active. Become truly supportive. Spend a little time; give it some thought. Then, pick a soldier, any soldier. Be the rock, if only briefly, and bear his weight.

November 11, 2012

The Fine Print

In case you missed it, there was a bit of a dust-up earlier this week over an opinion piece by Sarah Mesle featured on the Los Angeles Review of Books site. I won’t recap the entire article–go read it and all the comments here–but the gist is the author moaned about the good old days where books saw the successful transition of boys from happy childhood into powerful manhood and wondered just what contemporary YA books might be offering boys; whether the role models found in characters like Edward Cullen and Jacob Black, both “barely-contained monsters,” are the best we could muster nowadays. And, yes, predictably, a lot of people weighed in. A few even had good things to say.

I’m not exactly joining the fray, but it seems to me that, time periods and conventional notions of masculinity and societal expectations aside, this is another of those proverbial tempests in a teacup: a lot of fru-fru hand-wringing over nothing. So some of the boys in some books are beasts, and others are worried about their masculinity, and still others are confronted with terrible situations and make bad choices–and so what? There are so many books out there, you can find examples to bolster just about any argument you want to make. I can think of some fine examples of contemporary middle grade and YA lit–Gary Schmidt and Patrick Ness jump to mind right off the bat–where boys are neither beasts nor angels, and many of the adults aren’t too shabby either.

To be quite frank, however, when I digested some of Mesle’s misgivings, one thing that really surprised me: no one mentioned genre–and genre’s everything. Strip away the twinkly vampires and slavering wolves, and what you’ve got are Jacob’s hunky six-pack and Edward’s soulful eyes. What you’ve got is a YA romance, pure and simple, and one that any person who’s spent any time with bodice-rippers instantly recognizes. I have no idea what Stephanie Meyer was thinking in terms of the guys when she wrote the series, and it doesn’t really matter because she hews to the demands of the genre. Nearly all romance revolves around does he or doesn’t she, will he or won’t she? The choices are frequently bald and somewhat stereotypical; the men and women are types: Darcy’s a prideful guy with a heart of gold; Willoughby’s a scoundrel; Marianne’s willful and intolerant; Jane’s mother is a fluttery idiot–and so what? I’ll bet dollars to doughnuts that Jane Austen was as completely unconcerned with whether her male characters provided young men with appropriate role models as Nora Roberts is about whether any guy’s going to pick up, say, Dance Upon the Air, and decide that, yep, a girl needs a smack now and then. All Austen wanted was to get you to root for Jane and Darcy–and sell her book. Whether you’re talking Nora Roberts or Jane Austen, offering role models is completely beside the point. You write the characters your story demands, and that’s no less true for Meyer who–I just bet–was mainly about showing her readers a good time.

I disagree completely with one person who commented that it was “hardly unfair to ask literature to shine a light on the way gender is changing…” or redeem masculinity. Say what? Why should literature have to do any of that? I don’t know too many writers who approach a book with a mission in mind.

Besides, was anyone worried about this was I was a kid and there really wasn’t young adult literature per se? I grew up reading classics, sure, but also tons of science fiction (the YA lit of my day). For the most part, those books were written by guys for guys and about guys–and I didn’t care. At all. I also don’t recall anyone getting all worried that literature was somehow failing to give me suitable female role models to manage the transition into adulthood. Or maybe people were worried, but me being a kid, they didn’t tell me about it and I had, oh I don’t know, parents and teachers and other adults as role models. Now that doesn’t mean that I didn’t want to grow up to be Captain Kirk’s girlfriend (albeit I had superpowers and frequently saved the ship); armed with my trusty blaster, I played endless games of Lost in Space (although, yes, I admit it: they always picked me to play the mom and I remember being so focused on making dinner for Will and Dr. Smith after a hard day of fending off aliens). But those obsessions don’t seem to have done me any irreparable harm nor do I believe they told me anything about how to be a young woman. What they afforded were types to slip into and identities to try on–and discard.

So I read my share of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens and George Eliot and Frank Herbert and Arthur C. Clarke, Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Greg Bear and Anne McCaffrey and Lois McMaster Bujold and . . . Well, I won’t bore you with the list because it’s a long one. But my point is that while I read classics which were stories of girls principally worried about marriage and their reputations, I also devoured more contemporary books which were, with only a few exceptions, either profoundly pessimistic meditations on the fate of humanity or about young men out to kick some serious alien butt–and a few young women who were, yes, ready to fall in love, not overly concerned with their nails, and still plenty capable when it came to saving the planet, mussed hair notwithstanding. And I read about some splendidly evil men and women, too–because beastliness is, quite frequently and sorry to say it, very entertaining.

Sorry, but read the fine print of my job description: no book has to do or be anything more than it is, a private fantasy cooked up in a writer’s head and made public. The only obligation of any literature and art is to entertain, and not one whit more. All this concern about role models or the lack thereof ignores the fact that whatever any writer puts on paper says something far more about the author than it does society. Meyer made her guys as she did because she liked them that way, and those characters fit the needs of her story and its genre. Ditto Collins; ditto Rowling. Ditto me.

Maybe this benighted view means I’ll always be a hack or something and never do or write anything important, that’s any kind of beacon, but turning up the wattage isn’t in my job description either. Books do not have to instruct or offer social criticism; books do not have to shed light on anything. If they do or can, great. But, in the end, books are entertainment; readers crack the spine with the expectation of becoming someone somewhere else; and the only obligation any writer has is to tell the very best and most entertaining story she can. It is what every reader should and has the right to demand.

October 28, 2012

The (Vanishing) Art of Conversation

Nothing profound today, just an observation.

Now, I love serendipity. Right before I headed on my way to the Chippewa Valley Book Festival, I realized that my husband had taken my little iPod pluggie thingie . . . you know, that doohickey that allows you to plug your iPod into your radio? Now, this had me seriously PO’ed because I was about to take a VERY long drive with a very SHORT turnaround: 5 hours each way in a 36-hour period. When you factor in things like sleep and all the activities I had planned for the next day (three school visits) before I had to head back and then get into the car again the very next day for yet another appearance (a 3-hour drive one way) . . . that’s a heck of a lot of time in the car that I was planning to put to good use listening to an audiobook that I’d downloaded especially for this trip now wasted.

So, instead, I punched in the local NPR affiliate and let public radio keep me company on that very long drive. Now the lovely thing about Wisconsin is we’ve got coverage pretty much all over the state, and most of it effortlessly bleeds into the other, so you really don’t miss much. Of course, when you listen to the same news once over (because All Things Considered repeats), that’s a drag.

Anyway, I’m driving along; it’s a pretty day, nice autumn colors, good weather, that kind of thing. Spotted a ginormous bald eagle on my way up, too, maybe twenty miles outside of Wausau. As amazing as the eagle was, that wasn’t the interesting part of the trip, though. Instead, what REALLY held my interest was a fabulous Fresh Air, a program I rarely listen to not only because I’m not all that interested in most of the guests (sorry, but it’s true), but it’s on at the wrong time of day where I live. This time, though, because I was trapped in the car, I heard a fabulous interview with Sherry Turkle, a clinical psychologist, who’s the founder of MIT’s Initiative on Technology and the Self. Her main focus is studying the ways technology has changed the way we interact with one another. Her newest book, Alone Together: How We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, addresses something I’ve written about before: how ironic it is that, in this age of increased connectivity, our interpersonal connectedness–our ability to meaningfully communicate with one another–has suffered. What I found especially intriguing were her research findings on how huge the impact adults’ anxieties over not in being in touch with their kids 24/7 is, and how enormously detrimental these fears are to a kid’s emotional development, particularly as it relates to privacy, the capacity to be alone, and to disengage from one’s parents (a pivotal milestone in adolescent development) those parental concerns are. I’m not going to recapitulate the entire interview; if you’re interested, take a listen. (Well worth it, I promise, and food for thought–really.)

Now, as a shrink, I didn’t find any of Turkle’s concerns alarmist in the slightest. But, frankly, one thing I hadn’t paid much attention to was kids’ preferred modes of engagement. That is, we kind of all expect adolescents to hesitate to be outwardly engaged, know what I’m saying? They’re the ones who’ll slouch in their chairs, kind of dare you to impress or excite them, and heaven forbid, they ask the first question. (Once a couple kids get the ball rolling, though, then it’s like the group has received permission to become involved and excited. Like Kohler High School where I spoke the week before . . . wow, those kids really got into it and we could’ve kept going. But you got to hope for those two or three brave souls to start things off.)

During the festival–but particularly after–I was reminded of Turkle’s work when it came to engaging kids. I spoke at two middle schools and one high school, and while I enjoyed each venue, the difference between the willingness of the younger kids to allow themselves to be engaged and talkative and excited versus the older kids was obvious. The last middle school, Northstar, we talked for a good ninety minutes and were still going strong when the asst. principal had to intervene and send the kids off to resource. This is no surprise, mind you; if you know adolescents, then you look at the high school kids and shrug and understand this comes with the territory.

But what did make me think about Turkle’s work was when a) the high school librarian emailed to say that the kids were so excited by my presentation that they’d descended in droves to find my books and b) a couple of the high school kids got in touch to ask questions and tell me how much they liked the presentation . . . but through Facebook and Twitter.

Which was kind of interesting.

Now, I get a lot of emails, tweets, and FB messages; most authors do. The middle grade kids from two of the Dublin schools I toured last year still stay in touch, but they were the most involved at the time, too. Here, though, clearly those high school students were plenty interested, but expressing that, out loud and at the time, wasn’t cool (for whatever reason). Maybe this is why I always make sure to tell kids they can contact me through the usual social media or my website, and that I will always answer (so long as they’re polite).

I think what I’ve observed is a microcosm of what Turkle’s seen. Since I am a shrink, I have noticed that so many older kids, those raised with cells, have a lot of trouble both making eye contact during and flat-out having a sustained–and uncontrolled–conversation. Do I wonder what this means for kids’ development in particular and notions of privacy more generally? You bet.

I waffle about whether it’s better to meet with large groups or small; I’ve had great experiences with each. Smaller groups imply conversation as a given while large groups foster anonymity. But, on the other hand, the dynamics of a group are quite powerful, and once you can engage a couple kids, then it’s like a row of dominoes: the questions keep coming and the conversation flows.

What I don’t doubt is this: it is important for us, as authors, to actively engage kids in the ways our books invite. That means, I think, that we have to model how to have conversations with kids who may not know how to do this very well. To that end, the more directly we can connect–eye contact, face to face–the greater our ability to touch kids. Yes, by all means, keep in touch after the fact. Be available. But a text is not a person; a Skype visit is not a flesh and blood person; a blog can not engage the way you–your presence–can. In a way, our books open the door to a conversation. The least we can do is actually have one.

October 14, 2012

When Story Comes Together

This will be short and sweet, just a nice little bon mot I want to share. This may not seem like much either, but trust me: the moment itself was huge.

Earlier this week, my Egmont USA editor, Greg Ferguson, and I were going over his comments on MONSTERS, the last book in the ASHES trilogy, and we’d been on the phone a good hour and a half before finally getting around to talking about the last scene and sequence. Greg asked a great question about how I wanted people to feel when all was said and done; I told him; and then he mentioned that, well, he thought that was true and the tone was nearly there, but he really suggested that we needed to look at this one sentence about three, four paragraphs from the very end. I was a little puzzled because it seemed like a perfectly fine line to me. But then he read the line out loud a couple times, and it was very strange . . . but hearing it come out of someone else’s mouth really was a lightbulb moment. I realized then that he was onto something; there was something not quite right about the sentence, although I was darned if I knew what it was.

So we played around with the sentence, pulling it apart, looking at all the words. I wish I could say that I figured it out first, but it was Greg who said, “Well, what if we get rid of the word but? Change it from a conditional to an affirmation, something positive.” So he did just that, read the sentence back–and damn, if that one little word wasn’t the make-or-break moment. Simply brilliant.

Why do I even dwell on this? Why is it worth tucking away as one of those fabulously collaborative moments that, all too often, we don’t let ourselves experience? Because: sometimes I think writers can get proprietary, losing sight of the huge contribution a very good editor can make toward shaping a manuscript. I know a ton of writers who get all torqued when editors come at them with revisions or comments. I’ve already admitted that, yes, the first edit letter I ever got from Greg made me collapse into a weeping puddle of goo because it was so detailed, I thought the guy truly hated what I’d written. It took my husband to observe that, you know, the guy loved the series or he wouldn’t have bought it; and another pro writer friend to point out that an editor who invested this much into producing such detailed notes and questions was a) rare and b) someone from whom I could learn a great deal.

If there’s one thing I’ve repeated over and over again and in many different venues, it’s this: not every word deserves to live. A writer has to be ruthless when it comes to editing out extraneous stuff, and I’m pretty good when it come to throttling up my weed-whacker. Normally, I’ll kill about 15-20% of a final manuscript. I’d like to think that I catch every errant word, but of course, I don’t. No one does. But I guess I’m fixated on that single moment as a terrific example of what working with a gifted editor can be: not dictatorial but collaborative. An editor like Greg is not only going through a manuscript with a flea comb; he’s not only interested in pacing. He’s interested in how a book will make people feel. He’s invested in clarity. We agonized over one bloody line because we both wanted the message to come across in a very particular way. This wasn’t about killing a word; it was about reinforcing an emotion.

Now, am I saying that we let editors rewrite our work? No. Do we always agree? Of course not. Yes, we spin the stories. Yes, sometimes it can feel as if the comments are nits and silly; I can always tell when Greg’s getting punchy from the tone of a question, and we’re comfortable enough with one another now that I can kid him about it, too.

So, yeah, stick to your guns; defend your work because, when push comes to shove, no one cares as much about your book as you. But always remember, guys: The best editors are, first and foremost, tremendous readers, people who want to be swept away into that perfect moment when story comes together and language does not fail.

October 5, 2012

Who Brought the Olives?

Drop by Behind a Million and One Pages today and find out what I do when I get that negative review. :’-(

October 4, 2012

Emily’s Reading Room Blog Stop

Want to know why I like dark and creepy? Drop by Emily’s Reading Room and find out!

September 30, 2012

What Lives in My Trunk

Earlier this week, I was scheduled to do a live audio-interview on Bookspark. As with most tech, Murphy’s Law prevailed; no one could sign into the site; and the evening looked like a bust. I just happened to be moaning on my publisher’s FB page about this because she and a bunch of other folks had wanted to virtually attend. Long story short, she called; we moaned together; then I suggested we just move the event to Twitter and do a live chat there. Smart move: we had a great discussion (we even “trended,” which, I gather, is a good thing), got tons of participation and fabulous questions, and went for over an hour before I had to beg off and break the fast, or fall on my nose.

One question from that which stuck with me revolved around whether or not I’d ever run into a story I just couldn’t write or tell. My response at the time wasn’t disingenuous; I said that I kept working until I got it right–and that is true. I tend to be a drudge. OTOH, I went to medical school, so that figures. We were all drudges.

But when I took a step back and thought about it, I realized that, of course, there are tons of stories I’ve been unable to tell. Either they die in outline form (the most frequent and least painful way, frankly, because you realize halfway through that what you thought was a great idea wasn’t), fail to find an editor, or languish in the trunk every storyteller has in that dark closet because you know there’s something wrong . . . but you just don’t know what.

Only later, when you’ve either gotten distance or better at the craft–and, frequently both–do you realize why the story defeated you. Some you’re able to redraft (never try to “fix” a story that didn’t work; by definition, that’s one dog that just won’t hunt), as I did with ASHES. From others, I’ve lifted ideas and scenes to use in other stories, not verbatim because, again, the setups themselves didn’t work.

An example: there was one basic, overarching setup for a TREK novel that I actually carried two-thirds of the way through (an origin story about the Borg) before deciding that no one would ever actually LET me write a TREK novel. Years later, when I’d done just that (and many stories and novellas in the universe), I dredged up my original idea because, you know, I just really liked it. That idea was stuck in my craw; it was a cautionary, sweeping kind of story I felt compelled to write. So I redrafted the entire thing to the parameters of a TREK spin-off series I was writing for (SCE) and finally got to see my book become reality as a two-parter, WOUNDS, and the thing was popular to boot (enough that I earned out and made royalties . . . a big deal).

The story fit much better into that universe. Not to be immodest or anything, but whenever you do an “origin” story for a universe, it’s a risky proposition. You’re mucking with a basic tenet of that universe, something editors tend to be protective of and with good reason. I even hedged at the end of my book because I didn’t want to run afoul of the canon. But I was blessed with an editor willing to take those risks, and the story was so successful–so interesting–that he and I planned another spin-off series based on those characters (a kind of TREK CSI). Unfortunately, the SCE series was cancelled, and so that went nowhere. Which sucked because my poor characters were left in limbo. One of the dangers of work-for-hire: if a series is cancelled, it’s like all your great ideas–your babies–get orphaned. Sometimes you can scrub off the serial numbers. Many times, you can’t. Again, better just to redraft. With these characters, I couldn’t, so now I’ll NEVER know what happens next.

OTOH, that book was an example of an idea whose time finally came. Before then, I hadn’t grown into my writing chops enough to pull it off. I was trying to tell the wrong story at the wrong time.

So, have stories defeated me? Oh, yeah. Have I lived through the trauma to tackle them another day? Yes, and frequently, I’m able to see why they got the upper-hand to begin with. There are tons of novelists who brush off trunk novels–things they either were unable to sell or couldn’t quite pull off–spruce ‘em up, bring ‘em out. Some writers even tell you when they haven’t changed much and, sometimes, it shows. I guess my feeling, and I can only speak for my own stuff . . . Ils, honey, if it sucked the first time through, it’ll suck now. You really want your name on stuff that sucks?

For me, what lives in my trunk: my failures, either in execution, conception, or both. But you really can learn from your mistakes. Sometimes, you even get a do-over.

***

And now for something completely different:

Calling all film makers! Egmont USA is hosting a SHADOWS: Book Two of the Ashes Trilogy book trailer contest. To enter simply read SHADOWS and then submit your awesome book trailer to ashestrilogy@yahoo.com. Entries should be 30-45 seconds in length and should not exceed 3MB. We’ll be accepting entries from now until Halloween!

The winner will receive a customized ASHES pack and signed copies of both ASHES and SHADOWS.

Now get filming!