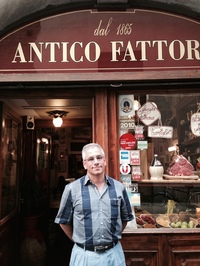

John Lauricella

Goodreads Author

Born

Brooklyn, The United States

Website

Genre

Influences

Don DeLillo; Ward Just; Kafka; Calvino; Camus; Nabokov; Joan Didion; J

...more

Member Since

May 2013

URL

https://www.goodreads.com/johnlauricella

To ask

John Lauricella

questions,

please sign up.

Popular Answered Questions

|

2094

—

published

2014

—

4 editions

|

|

|

Hunting Old Sammie

—

published

2013

—

5 editions

|

|

|

The Pornographer's Apprentice

|

|

|

Home Games: Essays on Baseball Fiction

—

published

1999

|

|

|

Home Games: Essays on Baseball Fiction

|

|

|

THE CHINA PLOT

|

|

|

2094

—

published

2014

|

|

|

Unforgettable

|

|

|

Unforgettable

|

|

John’s Recent Updates

|

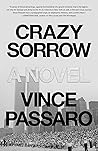

John Lauricella

rated a book it was amazing

|

|

| My newest favorite book, just read. I bought it when it came out because I knew Passaro’s name from his reviews in Harper’s and recognized a kindred sensibility. Plus, I liked his prose style. Turns out, this novel is close to something I might have ...more | |

|

John Lauricella

started reading

|

|

|

John Lauricella

started reading

|

|

|

John Lauricella

started reading

|

|

|

John Lauricella

started reading

|

|

|

John Lauricella

rated a book really liked it

|

|

|

John Lauricella

rated a book it was ok

|

|

|

John Lauricella

wants to read

|

|

|

John Lauricella

rated a book it was amazing

|

|

|

John Lauricella

rated a book liked it

|

|

“Jenna is acting strange. Weeping, moping, even remarks tending toward belittlement Melmoth might tolerate (although he cannot think why; she is not his wife and even in human females PMS is a plague of the past) but when he caught her lying about Raquel—udderly wonderful, indeed—he knew the problem was serious.

After sex, Melmoth powers her down. He retrieves her capsule from underground storage, a little abashed to be riding up with the oblong vessel in a lobby elevator where anyone might see. Locked vertical for easy transport, the capsule on its castors and titanium carriage stands higher than Melmoth is tall. He cannot help feeling that its translucent pink upper half and tapered conical roundness make it look like an erect penis. Arriving at penthouse level, he wheels it into his apartment. Once inside his private quarters, he positions it beside the hoverbed and enters a six-character alphanumeric open-sesame to spring the lid. On an interior panel, Melmoth touches a sensor for AutoRenew. Gold wands deploy from opposite ends and set up a zero-gravity field that levitates Jenna from the topsheet. As if by magic—to Melmoth it is magic—the inert form of his personal android companion floats four feet laterally and gentles to rest in a polymer cradle contoured to her default figure.

Jenna is only a SmartBot. She does not breathe, blood does not run in her arteries and veins. She has no arteries or veins, nor a heart, nor anything in the way of organic tissue. She can be replaced in a day—she can be replaced right now. If Melmoth touches “Upgrade,” the capsule lid will seal and lock, all VirtuLinks to Jenna will break, and a courier from GlobalDigital will collect the unit from a cargo bay of Melmoth’s high-rise after delivering a new model to Melmoth himself. It distresses him, how easy replacement would be, as if Jenna were no more abiding than an oldentime car he might decide one morning to trade-in. Seeing her in the capsule is bad enough; the poor thing looks as if she is lying in her coffin. Melmoth does not select “Power Down” on his cerebral menu any more often than he must. Only to update her software does Melmoth resort to pulling Jenna’s plug. Updating, too, disturbs him. In authorizing it, he cannot pretend she is human. [pp. 90-91]”

― 2094

After sex, Melmoth powers her down. He retrieves her capsule from underground storage, a little abashed to be riding up with the oblong vessel in a lobby elevator where anyone might see. Locked vertical for easy transport, the capsule on its castors and titanium carriage stands higher than Melmoth is tall. He cannot help feeling that its translucent pink upper half and tapered conical roundness make it look like an erect penis. Arriving at penthouse level, he wheels it into his apartment. Once inside his private quarters, he positions it beside the hoverbed and enters a six-character alphanumeric open-sesame to spring the lid. On an interior panel, Melmoth touches a sensor for AutoRenew. Gold wands deploy from opposite ends and set up a zero-gravity field that levitates Jenna from the topsheet. As if by magic—to Melmoth it is magic—the inert form of his personal android companion floats four feet laterally and gentles to rest in a polymer cradle contoured to her default figure.

Jenna is only a SmartBot. She does not breathe, blood does not run in her arteries and veins. She has no arteries or veins, nor a heart, nor anything in the way of organic tissue. She can be replaced in a day—she can be replaced right now. If Melmoth touches “Upgrade,” the capsule lid will seal and lock, all VirtuLinks to Jenna will break, and a courier from GlobalDigital will collect the unit from a cargo bay of Melmoth’s high-rise after delivering a new model to Melmoth himself. It distresses him, how easy replacement would be, as if Jenna were no more abiding than an oldentime car he might decide one morning to trade-in. Seeing her in the capsule is bad enough; the poor thing looks as if she is lying in her coffin. Melmoth does not select “Power Down” on his cerebral menu any more often than he must. Only to update her software does Melmoth resort to pulling Jenna’s plug. Updating, too, disturbs him. In authorizing it, he cannot pretend she is human. [pp. 90-91]”

― 2094

“He finds a basket and lays fish inside it. Charcoal is in a wooden bucket. Enrique lifts it, basket in his other hand, and moves through shadow toward daylight.

A presence makes him turn his head. He sees no one, yet someone is there.

He sets down fish and charcoal. Straightening up, Enrique slips his Bowie knife clear of its sheath. He listens, tries to sense the man’s place. This intruder lies low. Is concealed. Behind those barrels? In that corner, crouched down? Enrique shuts his eyes, holds his breath a moment and exhales, his breath’s movement the only sound, trying to feel on his skin some heat from another body.

Where?

Enrique sends his mind among barrels and sacks, under shelves, behind posts and dangling utensils. It finds no one.

He is hiding. Wants not to be found. Is afraid.

If he lies under a tarpaulin, he cannot see. To shoot blind would be foolish: likely to miss, certain to alert the others.

Enrique steps around barrels, his boots silent on packed sand. Tarps lie parallel in ten-foot lengths, their wheaten hue making them visible in the shadowed space. They are dry and hold dust. All but one lies flat.

There.

Enrique imagines how it will be. To strike through the tarp risks confusion. Its heavy canvas can deflect his blade. But his opponent will have difficulty using his weapon. He might fire point-blank into Enrique’s weight above him, bearing down. To pull the tarpaulin clear is to lose his advantage; he will see the intruder who will see him. An El Norte mercenary with automatic rifle or handheld laser can cut a man in half.

Knife in his teeth, its ivory handle smooth against lips and tongue, Enrique crouches low. Pushing hard with his legs, he dives onto the hidden shape. The man spins free as Enrique grasps, boots slipping on waxed canvas. His opponent feels slight, yet wiry strength defeats Enrique’s hold. He takes his knife in hand and rips a slit long enough to plunge an arm into his adversary’s shrouded panic. Enrique thrusts the blade’s point where he believes a throat must be. Two strong hands clamp his arm and twist against each other rapidly and hard. Pain flares across his skin. Enrique wrests his arm free and his knife flies from his grasp and disappears behind him. He clenches-up and, pivoting on his other hand, turns hard into a blind punch that smashes the hidden face.

The dust of their struggle rasps in Enrique’s throat. His intended killer sucks in a hard breath and Enrique hits him again, then again, each time turning his shoulder into the blow. The man coughs out, “Do not kill me.”

Enrique knows this voice. It is Omar the Turk. [pp. 60-61]”

― 2094

A presence makes him turn his head. He sees no one, yet someone is there.

He sets down fish and charcoal. Straightening up, Enrique slips his Bowie knife clear of its sheath. He listens, tries to sense the man’s place. This intruder lies low. Is concealed. Behind those barrels? In that corner, crouched down? Enrique shuts his eyes, holds his breath a moment and exhales, his breath’s movement the only sound, trying to feel on his skin some heat from another body.

Where?

Enrique sends his mind among barrels and sacks, under shelves, behind posts and dangling utensils. It finds no one.

He is hiding. Wants not to be found. Is afraid.

If he lies under a tarpaulin, he cannot see. To shoot blind would be foolish: likely to miss, certain to alert the others.

Enrique steps around barrels, his boots silent on packed sand. Tarps lie parallel in ten-foot lengths, their wheaten hue making them visible in the shadowed space. They are dry and hold dust. All but one lies flat.

There.

Enrique imagines how it will be. To strike through the tarp risks confusion. Its heavy canvas can deflect his blade. But his opponent will have difficulty using his weapon. He might fire point-blank into Enrique’s weight above him, bearing down. To pull the tarpaulin clear is to lose his advantage; he will see the intruder who will see him. An El Norte mercenary with automatic rifle or handheld laser can cut a man in half.

Knife in his teeth, its ivory handle smooth against lips and tongue, Enrique crouches low. Pushing hard with his legs, he dives onto the hidden shape. The man spins free as Enrique grasps, boots slipping on waxed canvas. His opponent feels slight, yet wiry strength defeats Enrique’s hold. He takes his knife in hand and rips a slit long enough to plunge an arm into his adversary’s shrouded panic. Enrique thrusts the blade’s point where he believes a throat must be. Two strong hands clamp his arm and twist against each other rapidly and hard. Pain flares across his skin. Enrique wrests his arm free and his knife flies from his grasp and disappears behind him. He clenches-up and, pivoting on his other hand, turns hard into a blind punch that smashes the hidden face.

The dust of their struggle rasps in Enrique’s throat. His intended killer sucks in a hard breath and Enrique hits him again, then again, each time turning his shoulder into the blow. The man coughs out, “Do not kill me.”

Enrique knows this voice. It is Omar the Turk. [pp. 60-61]”

― 2094

“Julietta’s dark hair is glossy and straight and smells like apples. Armand kneels beside her and holds his head close. Her eyelashes are long and delicately curved in a way people a hundred years ago would have described as buggy whips, a phrase no one uses any¬more because no one understands. In this way knowledge is lost.”

― Hunting Old Sammie

― Hunting Old Sammie

“Your statement ... tells a very fine story; but pray, was not your stock a little heavy a while ago? downward tendency? Sort of low spirits among holders on the subject of that stock?"

"Yes, there was a depression. But how came it? who devised it? The 'bears,' sir. The depression of our stock was solely owing to the growling, the hypocritical growling, of the bears."

"How hypocritical?"

""Why, the most montrous of all hypocrites are these bears: hypocrites by inversion; hypocrites in the simulation of things dark instead of bright; souls that thrive, less upon depression, than the fiction of depression; professors of the wicked art of manufacturing depressions; spurious Jeremiahs; sham Heraclituses, who, the lugubrious day done, return, like sham Lazaruses among the beggars, to make merry over the gains got by their pretended sore heads--scoundrelly bears!"

"You are warm against these bears?"

"If I am, it is less from the remembrance of their stratagems as to our stock, than from the persuasion that these same destroyers of confidence, and gloomy philosophers of the stock-market, though false in themselves, are yet true types of most destroyer of confidence and gloomy philosophers, the world over. Fellows who, whether in stocks, politics, bread-stuffs, morals, metaphysics, religion--be it what it may--trump up their black panics in the naturally-quiet brightness, solely with a view to some sort of covert advantage. That corpse of calamity which the gloomy philosopher parades, is but his Good-Enough-Morgan."

"I rather like that," knowingly drawled the youth.

~The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade”

―

"Yes, there was a depression. But how came it? who devised it? The 'bears,' sir. The depression of our stock was solely owing to the growling, the hypocritical growling, of the bears."

"How hypocritical?"

""Why, the most montrous of all hypocrites are these bears: hypocrites by inversion; hypocrites in the simulation of things dark instead of bright; souls that thrive, less upon depression, than the fiction of depression; professors of the wicked art of manufacturing depressions; spurious Jeremiahs; sham Heraclituses, who, the lugubrious day done, return, like sham Lazaruses among the beggars, to make merry over the gains got by their pretended sore heads--scoundrelly bears!"

"You are warm against these bears?"

"If I am, it is less from the remembrance of their stratagems as to our stock, than from the persuasion that these same destroyers of confidence, and gloomy philosophers of the stock-market, though false in themselves, are yet true types of most destroyer of confidence and gloomy philosophers, the world over. Fellows who, whether in stocks, politics, bread-stuffs, morals, metaphysics, religion--be it what it may--trump up their black panics in the naturally-quiet brightness, solely with a view to some sort of covert advantage. That corpse of calamity which the gloomy philosopher parades, is but his Good-Enough-Morgan."

"I rather like that," knowingly drawled the youth.

~The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade”

―

“Whoever looks for the writer’s thinking in the words and thoughts of his characters is looking in the wrong direction. Seeking out a writer’s “thoughts” violates the richness of the mixture that is the very hallmark of the novel. The thought of the novelist that matters most is the thought that makes him a novelist.

The thought of the novelist lies not in the remarks of his characters or even in their introspection but in the plight he has invented for his characters, in the juxtaposition of those characters and in the lifelike ramifications of the ensemble they make — their density, their substantiality, their lived existence actualized in all its nuanced particulars, is in fact his thought metabolized.

The thought of the writer lies in his choice of an aspect of reality previously unexamined in the way that he conducts an examination. The thought of the writer is embedded everywhere in the course of the novel’s action. The thought of the writer is figured invisibly in the elaborate pattern — in the newly emerging constellation of imagined things — that is the architecture of the book: what Aristotle called simply “the arrangement of the parts,” the “matter of size and order.” The thought of the novel is embodied in the moral focus of the novel. The tool with which the novelist thinks is the scrupulosity of his style. Here, in all this, lies whatever magnitude his thought may have.

The novel, then, is in itself his mental world. A novelist is not a tiny cog in the great wheel of human thought. He is a tiny cog in the great wheel of imaginative literature. Finis.”

―

The thought of the novelist lies not in the remarks of his characters or even in their introspection but in the plight he has invented for his characters, in the juxtaposition of those characters and in the lifelike ramifications of the ensemble they make — their density, their substantiality, their lived existence actualized in all its nuanced particulars, is in fact his thought metabolized.

The thought of the writer lies in his choice of an aspect of reality previously unexamined in the way that he conducts an examination. The thought of the writer is embedded everywhere in the course of the novel’s action. The thought of the writer is figured invisibly in the elaborate pattern — in the newly emerging constellation of imagined things — that is the architecture of the book: what Aristotle called simply “the arrangement of the parts,” the “matter of size and order.” The thought of the novel is embodied in the moral focus of the novel. The tool with which the novelist thinks is the scrupulosity of his style. Here, in all this, lies whatever magnitude his thought may have.

The novel, then, is in itself his mental world. A novelist is not a tiny cog in the great wheel of human thought. He is a tiny cog in the great wheel of imaginative literature. Finis.”

―

“Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe, 45

With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she,

Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

The lady of situations. 50

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

The Hanged Man. Fear death by water.”

―

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe, 45

With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she,

Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

The lady of situations. 50

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

The Hanged Man. Fear death by water.”

―

“I think up to a point people's characters depend on the toilets they have to shut themselves up in every day. You get home from the office and you find the toilet green with mould, marshy: so you smash a plate of peas in the passage and you shut yourself in your room and scream.”

―

―

“Don’t walk in front of me… I may not follow

Don’t walk behind me… I may not lead

Walk beside me… just be my friend”

―

Don’t walk behind me… I may not lead

Walk beside me… just be my friend”

―

Authors Only

— 128 members

— last activity Aug 31, 2025 07:54AM

Authors Only

— 128 members

— last activity Aug 31, 2025 07:54AM

This group is meant for authors only, and members will be accepted if they have formatted, GR-approved GoodReads author profiles. Authors here will ha ...more

THE Group for Authors!

— 12967 members

— last activity 14 hours, 58 min ago

THE Group for Authors!

— 12967 members

— last activity 14 hours, 58 min ago

This is a group for authors to discuss their craft, as well as publishing and book marketing.