Adrian Collins's Blog, page 51

June 29, 2024

REVIEW: Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

Octavia E. Butler’s been on my TBR forever, so I jumped at the chance to review Headline’s beautiful new editions. Parable of the Sower hits the spot perfectly, balancing social criticism and complex characters with a timeless story. Set distinctly within the tradition of Afrofuturism, Parable of the Sower introduces the reader to a world ravaged by climate change, a world in which the lack of natural resources has driven society into small communities. As small, isolated communities tend to, they have regressed in mindset, growing more rigid in what they accept. And with that, Butler holds a mirror up to our collective faces.

While the book was initially published in 1993, the story starts in 2024 – and is no less relevant to this 2024. We meet Lauren, the story’s protagonist, as a teen chafing against society. Her role as a young woman is heavily regimented – until disaster hits. Having lost her home, Lauren and her companions set out to find safety in the north. The world is hostile, in terms of human dangers just as much as the lack of resources. The story takes place over a longer period of time, echoing the Canterbury Tales in their itinerant manner. The destination isn’t all that important, it is the journey that matters. This means Parable of the Sower isn’t fast-paced or stuffed with plot. The reader gets time to really get to know the characters, an aspect in which Butler’s work shines.

While the book was initially published in 1993, the story starts in 2024 – and is no less relevant to this 2024. We meet Lauren, the story’s protagonist, as a teen chafing against society. Her role as a young woman is heavily regimented – until disaster hits. Having lost her home, Lauren and her companions set out to find safety in the north. The world is hostile, in terms of human dangers just as much as the lack of resources. The story takes place over a longer period of time, echoing the Canterbury Tales in their itinerant manner. The destination isn’t all that important, it is the journey that matters. This means Parable of the Sower isn’t fast-paced or stuffed with plot. The reader gets time to really get to know the characters, an aspect in which Butler’s work shines.

There is no such thing as a good person in this world. Survival being uncertain doesn’t lend itself to caring about others. The characters are inherently selfish – as we all would be likely to be. And that’s part of what makes Parable of the Sower so compelling and keeps it relevant thirty years on. There are elements that didn’t quite work for me, though, despite loving the book as a whole. I struggled with the deeply entrenched gender roles (which made sense in the context of the world!) and with one relationship in particular. Age gap romance is something that’s a hard sell – for me – in the best of cases. Here, it’s interwoven with hierarchy and power, making it a very uncomfortable situation. This does stem from conversations moving on in the last three decades, showing perhaps not something that doesn’t exist, but something that doesn’t get as much traction in fiction these days. In any case, this is a tiny gripe with the book as a whole.

I don’t think I will stop thinking about Parable of the Sower anytime soon. Octavia E. Butler has created one of the great (foundational, even) works of speculative fiction and lives up to her stellar reputation. With these stunning new editions, there has never been a better time to pick up her books.

Read Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. ButlerThe post REVIEW: Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 28, 2024

REVIEW: House of the Dragon Season 2 Episode 1

House of the Dragon 2×1 “A Son for A Son” is the season premiere of the second season of House of the Dragon. The series, for those unfamiliar, a sequel to the immensely popular Game of Thrones series and deals with the events of “The Dance of the Dragons” that was a civil war between the Targaryen household of dragon-riders over who would be king of Westeros: Rhaenyra the King’s beloved daughter or his disliked male heir, Aegon.

While a big supporter of this series and a believer that it has done a lot to wipe the sour taste of Game of Thrones‘ season eight from viewers’ mouths, I have a lot of criticisms of season one. Simply put, the ten episodes jumped around one way too much and at least two seasons of story were crammed into one season in hopes of getting to the “good stuff” faster. Unfortunately, this severely impacted the pacing of the show as well as its characterization, which are the things that GOT fans love most.

While a big supporter of this series and a believer that it has done a lot to wipe the sour taste of Game of Thrones‘ season eight from viewers’ mouths, I have a lot of criticisms of season one. Simply put, the ten episodes jumped around one way too much and at least two seasons of story were crammed into one season in hopes of getting to the “good stuff” faster. Unfortunately, this severely impacted the pacing of the show as well as its characterization, which are the things that GOT fans love most.

House of the Dragon is a series that is generally lighter and softer than Game of Thrones with much less nudity and onscreen violence. However, it still maintains its incredibly dark themes as well as maintains antihero (verging on villainous) protagonists on both sides. The moral ambiguity that grimdark fans love will be notable throughout.

House of the Dragon begins with a new opening as we replace the dripping blood down a stone family tree of the Targaryens to, instead, be a tapestry that is woven with the stories of the Dance of the Dragon. I think this works very well as a visually distinct metaphor for the setting and better than the previous season. Still, it’s a surprising change and I wonder why they decided to make it given the stone family tree and blood one wasn’t bad.

House of the Dragon’s previous season ended with the death of Lucerys, one of Rhaenyra Targaryen’s children. Killed in an accident by Aemond Targaryen and his dragon, the result is that the Blacks and Greens are going to have a war no matter what. Kinslaying is the vilest taboo in Westeros, and no one would believe that he didn’t do it deliberately. I was waiting to see how Alicent and Otto Hightower would react to this stunning development. Well, I will have to keep waiting because it skips right past that.

We get a glimpse of the North that so far has played little role in the conflict. Still, we get some nice backstory about the past relationship between the Sarks and Targaryens. Also, a plot hole about how the dragons refuse to cross the Wall comes up because they didn’t make this a thing in Game of Thrones and the opposite being an actual plot point. Still, it’s nice to see the Wall again and a reminder of the importance of the struggle against the White Walkers.

Much of the episode deals with the aftermath of Aemond killing Lucerys despite the fact that we don’t see everyone’s immediate reaction. Rhaenyra is beside herself with grief and Daemon sees an opportunity to assert his position once more by promising vengeance. Fans of the book, Fire and Blood, will know who “Blood and Cheese” but newcomers will probably be shocked. Sadly, it lacks the power of the scene in the book because we haven’t had the characters developed enough to truly bond with them before things go horribly south.

There are some interesting developments in the characterization that I would have wanted more examination of as well. Aegon II is an utterly inept king and his brother is much better suited, which both brothers know. We also have Mysaria drop her godawful fake accent. House of the Dragon definitely has improved in several areas.

Overall, I think this was a solid episode, but I foresee this season suffering again from the fact that it is going to be an abbreviated season. Perhaps even worse because there will only be eight episodes this season. Really, I think House of the Dragon needed twelve-episode seasons, and it still feels like we’re running ahead past more character seasons. Still, I think it’s the best fantasy currently on television right now.

The post REVIEW: House of the Dragon Season 2 Episode 1 appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 27, 2024

REVIEW: Craft by Ananda Lima

Last Updated on June 28, 2024

Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil is Ananda Lima’s fiction debut. Craft is billed as a collection of short fiction, though I would argue it is more of a fragmentary novel. The collection’s hook is an unnamed author who has slept with the devil, their future interactions and how this impacted her. The named stories are interspersed with notes from the fictional author’s life, giving a sense of why these stories are as they are. Lima has previously published poetry, including the collection Mother/land and her background in poetry permeates her fiction, just as much as her Brazilian upbringing and life as an emigrant does.

Craft is certainly very far down the literary end of genre fiction. If that’s not your cup of tea, this isn’t the book for you. It is weird, experimental and unique, and ultimately, I came down on the side of really liking Craft. Early on, I did consider not finishing it as I was struggling to get invested, but for me it was well worth persevering with this special book – and just letting it do its thing rather than dwell on my expectations. The publisher compares this to The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, but I would add one big caveat to that: as written by James Joyce. To me, that’s the literary heritage of Craft, a book that gives the reader a lot of food for thought, that changes vastly between chapters and unashamedly experiments with voice and perspective.

Craft is certainly very far down the literary end of genre fiction. If that’s not your cup of tea, this isn’t the book for you. It is weird, experimental and unique, and ultimately, I came down on the side of really liking Craft. Early on, I did consider not finishing it as I was struggling to get invested, but for me it was well worth persevering with this special book – and just letting it do its thing rather than dwell on my expectations. The publisher compares this to The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, but I would add one big caveat to that: as written by James Joyce. To me, that’s the literary heritage of Craft, a book that gives the reader a lot of food for thought, that changes vastly between chapters and unashamedly experiments with voice and perspective.

I particularly enjoyed two of the stories, “Antropógaga” and “Idle Hands”, stories that epitomize the range of writing in Craft. The first, “Antropógaga” is an absurdist tale, reminiscent of early Russian fantasists, in which a woman gets addicted to a vending machine at work. Sounds fine, except what she eats are tiny humans, packaged in plastic. The story touches on the impact of perception and mass consumerism. dehumanizing to discuss humanity. “Idle Hands” on the other hand is one of the more experimental tales in Craft. This story consists of a series of peer-reviews of one of the fictional author’s stories in the context of a writing workshop. The reader doesn’t ever see the original story but learns much about the peers who write the notes. To me, these two stories really show off how Lima plays with structure and expectation, how she crafts a setting that comes alive. The stories themselves are connected through notes about the fictional author told in third person – like Lima, she is Brazilian, but has been in the US for years. With these interludes, Lima manages to interweave the stories with reflections on emigrant life, the demands of family and complications following your own destiny brings.

I found Craft to be weird and wonderful, a book that demands trust from the reader and rewards that trust. Lima is an author to watch, I’m very curious to read what she writes next.

Read Craft by Ananda LimaThe post REVIEW: Craft by Ananda Lima appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 26, 2024

REVIEW: A Poisoner’s Tale by Cathryn Kemp

With A Poisoner’s Tale, Cathryn Kemp whisks the reader to seventeenth century Rome. Giulia Tofana is a historical figure – a woman of myth and dark legend. She supposedly sold and distributed a poison to women suffering at the hand of their husbands, killing hundreds by proxy. I would argue that juggling murder with a perhaps greater positive impact makes her one of the most grimdark characters out there. Kemp’s historical novel puts the focus exactly there, smack on her moral greyness, to create a compelling narrative of a semi-fictional life.

There isn’t much known about the historical Giulia. Kemp takes that little information and weaves it into a story about poison, feminine rage and friendship. We follow Giulia from childhood through to middle age, to having an adult daughter. She learns how to brew acqua, the poison she distributes, from her mother in Sicily and takes that knowledge on to Naples and Rome, sharing it with a few trusted companions – and teaching her own daughter. Acqua is a family legacy. It’s not seen as a dangerous weapon, but as a way to liberate women. Of course, the number of men dropping dead with similar symptoms means Giulia gains quite the reputation… And attention from all the wrong places.

There isn’t much known about the historical Giulia. Kemp takes that little information and weaves it into a story about poison, feminine rage and friendship. We follow Giulia from childhood through to middle age, to having an adult daughter. She learns how to brew acqua, the poison she distributes, from her mother in Sicily and takes that knowledge on to Naples and Rome, sharing it with a few trusted companions – and teaching her own daughter. Acqua is a family legacy. It’s not seen as a dangerous weapon, but as a way to liberate women. Of course, the number of men dropping dead with similar symptoms means Giulia gains quite the reputation… And attention from all the wrong places.

A Poisoner’s Tale is incredibly compelling. I kept going back to sneak just one more chapter (or ten, if we’re being honest). Despite knowing how the story ends, the tension stays high throughout, making the reader root for a doomed cause. It has something of a trainwreck (in the very best way!) where you can see what will happen, how the story will go but you can’t look away despite your sense of impending doom. To me, that shows great mastery of craft – and I look forward to checking out whatever Kemp writes next.

I found Giulia to be an interesting character to follow. She is certainly flawed, and she’s aware of it. We see her make decisions that are based on emotions rather than logic quite a few times. To me, that makes her stand out. She strictly follows her own moral compass, even when it doesn’t quite fit society’s expectations. In a D&D universe, I’d call her lawful evil. And she cares. For her, it’s about helping women, the act of making poison a statement against the patriarchy. It was interesting to read about Giulia’s relationship with her own mother in contrast to Giulia’s relationship to her daughter. Her friends have become a family – though her role as a single mother, a woman without a husband is not something that comes up in the story.

In that regard, A Poisoner’s Tale feels a touch too modern. It is very rooted in its seventeenth century setting, but divorces the main characters’ outlook from it. Religion plays a big role in the novel, we are dealing with the (Spanish) inquisition after all. It feels like the way faith affects society, the belief in damnation, is passed over for the sake of telling a story. There are priests engaged in carnal activity, priests who get involved in the distribution of Giulia’s aqua. The pope himself is a significant character. There is no interrogation of these behaviours. The novel keeps “the behaviour and belief of the religious” completely apart from the women’s outlook on the world. And I feel adding a bit more nuance in this regard would have hugely strengthened the book as a whole.

Still, I’m picking at absolute details. I really enjoyed my time reading A Poisoner’s Tale and particularly how it blended a rich historical setting with a story that speaks to twenty-first century audiences. It doesn’t overload the reader with details, but makes the historical Giulia Tofana come to life, and imagines her as a person rather than the legendary murderer. Let’s raise a glass of acqua in Giulia’s honour.

Read A Poisoner’s Tale by Cathryn KempThe post REVIEW: A Poisoner’s Tale by Cathryn Kemp appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 25, 2024

An Interview with Jenn Lyons

Coming off the massive (yes, literally) A Chorus of Dragons series, Jenn Lyons is back with the standalone dragon fantasy The Sky on Fire. She plays with expectations and tropes, giving us a rich and detailed world in which dragons are not creatures softened and turned loyal. She was twice-nominated for the Astounding Award for Best New Writer and is a geek through and through, having a background in graphic design and video games. Her new book The Sky on Fire is great fun to read – and it was great to catch up with Jenn ahead of publication and talk dragons, mature characters and writing.

[GdM] Can you give our readers an elevator pitch for The Sky on Fire, please?

[GdM] Can you give our readers an elevator pitch for The Sky on Fire, please?

[JL] It’s Dragonriders of Pern meets Ocean’s 11. Probably the easiest elevator pitch I’ve ever done.

[GdM] Dragons are having a huge moment. What’s your impression of the trend and where does your fascination with dragons stem from?

[JL] My obsession with dragons probably stems from Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, which I saw as a small child. I was very taken with Maleficent, and it’s a feeling that’s never gone away. I’ve been obsessed with dragons for my entire life. So for me, this is less of a ‘moment’ than ‘just normal.’ Dragons have always been part of fantasy, though, so I don’t really see the current popularity as anything special, except that it’s being labeled as such.

[GdM] One of the things that has really made The Sky on Fire stand out is how dragons are not tools for human power struggles. The dragons are those who lead society. Can you talk a bit more about your ideas behind this?

[JL] – When I sat down to write this book, I was thinking quite a lot about its inspiration, of which the Ann MacCaffery books were a large part, and themes of dragonrider books in general. And one of the things that struck me is how in most books where dragons have riders (as opposed to the ones who go terrorizing the countryside until one sacrifices a virgin to them) the dragons are so loyal. So incredibly loyal and subservient. Often, they’re downright dog-like in their loyalty, even if they’re intelligent. So, a thought occurred to me: what if that wasn’t true? In most depictions, dragons are more powerful than their riders by significant degrees, so what would happen if the dragons knew that? It would turn the dynamic on its head, and I found that appealed to me a great deal.

[GdM] One last dragon question, then I’ll pester you with a new topic, I promise. I wanted to know more about the naming conventions of dragons. There’s such a range, from Overbite to Neveranimas. Is there a logic to it?

[JL] I created a language for the dragons, although it is, by nature of being something that humans don’t have the vocal capacity to pronounce, incomplete. In the case of Overbite, well, she’s not a dragon. She is an animal, just as T-Rex would be an animal, and her name as such was given by the person who raised her—Anahrod. The other names are a combination of the conlang and me sounding out syllables until I had something that I felt sounded sufficiently draconic.

[GdM] You introduce the reader to the concept of status/identity rings that show others who they are – and with them a queer-norm society. I found these fascinating – can you tell us a bit more about them and their use?

[JL] I will admit that the garden rings partly from my own frustration with dating. Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone just wore a little sign with their preferences? That way you’d know not to start flirting with someone who wasn’t interested, who was, or perhaps more significantly, be able to put a giant ‘keep away’ sign on oneself, no explanation required. As the ring concept developed, I was surprised to realize that I had, quite without meaning to, created a society that wasn’t heteronormative. That’s just another ring, after all.

(c) Mike Lyons

[GdM] I love a good heist, and so do these characters – and I expect you too. I’d love to hear about your ideas for the ideal heist you’d like to commit!

[JL] When I was a teenager, I used to concoct these rather elaborate fantasies about being a jewel thief. The problem, of course, is that the fantasy is very sexy, but the reality very different…

…which is not an admission. I’ve never committed a heist, just done a lot of research. In any event, the best heist…would probably need to have been committed forty years ago. They’ve gotten a lot harder to pull off in the 21st century.

[GdM] I found Anahrod to be a great leading character – she’s complex, she’s villainized, she’s going on middle-aged. What drew you to write The Sky on Fire about her specifically?

[JL] I must protest: she’s not really going on middle-aged, is she? I mean, she was fifteen when everything went to hell and it’s seventeen years later, so you do the math. (Editor’s note: to my great shame I did not do the math!) It is interesting to me to see that comparison used, however, because I think it says quite a lot about how fantasy is fixated on youth. It’s like the way Hollywood likes to cast actresses as mothers to stars that are the same age (or older) or the way everyone assumes that a fantasy book written by a woman must by YA.

To answer the actual question, though, I didn’t know I wanted to write about Anahrod specifically. She developed with the plot. If I was going to create a story about a rejected dragonrider, and as the background evolved, I had to ask myself what her experiences would’ve done to her. What I ended up with was this delightfully bitter and surly woman who’d had her dreams shattered and had been betrayed by everyone she loved. And now, years later, was finally being forced to confront her ghosts…and maybe get a little revenge, as a treat.

[GdM] That feeds into my next question: what do you see as the appeal of writing about mature characters, of stepping away from the naïve young protagonist we see so often?

[JL] I think it’s lovely to be able to write a main character who isn’t the ingenue or the chosen one. Something who has some dirt (and blood) under their nails, knows what they like, has seen things. We need more adults in fantasy who exist to be something other than the villain or the mentor who dies at the end of Act 1.

[GdM] You’ve come to The Sky on Fire after completing a massive epic fantasy series. What’s been your experience writing in a completely new setting? And what have you perhaps learned from your first series?

[JL] What can I say? It was a delight. You have to understand: I adore worldbuilding. So the chance to develop a new world from the ground up (or the solar system up, in this case) was a real treat. Obviously, the worldbuilding on The Sky on Fire couldn’t be as complete as what I did for A Chorus of Dragons, but then again, I didn’t have thirty years this time.

I think probably the biggest lesson I’ve learned is that I have an extraordinarily high tolerance for complexity, and so what is obvious to me is not obvious to virtually anyone else. I don’t have any regrets about how A Chorus of Dragons turned out, but if I had to do it again, I would have been a little more ruthless in eliminating some of the extraneous details that didn’t necessarily serve to further the main plot. I’ve learned to have a better appreciation for the negative spaces in my work.

[GdM] Romantasy is all the rage right now—but The Sky on Fire refuses to fit into the trend. Where do you see its role in the genre and how do you feel as an author who writes differently?

[JL] It’s like dragons: I think the only thing that’s new about romantasy is the label (and I know Jacqueline Carey has my back on this one) since romance has always been a commonly seen element of the fantasy genre. I don’t think it’s a bad thing to have the label if it makes it easier for readers to find the sorts of books they want. Certainly ‘Romance’ as a category is so large that it can be extremely intimidating for people trying to just dip in a toe, so from that point of view, being able to tell that a given book sits on the venn diagram overlap between the two genres is helpful. I just didn’t write The Sky on Fire to be that (although it has plenty of romance in it).

[GdM] I’d love to end with a fun question. Given it’s Pride Month and The Sky on Fire is a queer book, do you have any queer book recommendations for our readers?

[JL] John Wiswell’s Someone to Build a Nest In is delightful and highly recommended. As is Alexandra Rowland’s Running Close to the Wind (which I think comes out on June 11th). Freya Marske also has a book coming out this Fall called Swordcrossed—that one probably qualifies solidly as romantasy, and it’s great.

Read The Sky on Fire by Jenn LyonsThe post An Interview with Jenn Lyons appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

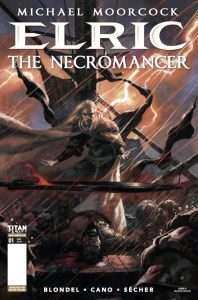

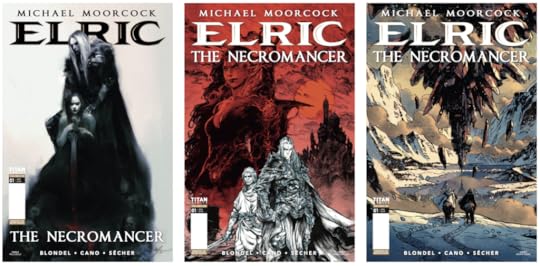

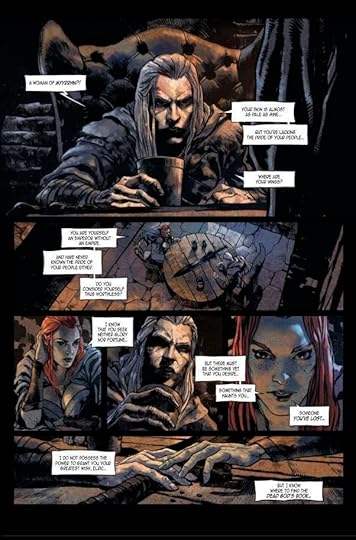

EXCLUSIVE first look at Elric the Necromancer by Jean-Luc Cano and Julien Blondel

For the first time, Elric the Necromancer will be printed in English! Adapted from the stories by, and with approval from, Michael Moorcock, this features his character Elric – who must face an epic threat without his legendary Stormbringer. Originally published in French, this is the first time the tale has been translated into English.

Written by Jean-Luc Cano and Julien Blondel, and with art from Valentin Secher, this gorgeous book is something you need to check out. This is the second of Titan Comic’s translations of Blondel and Cano’s Moorcock-approved works we’ve reviewed, having also reviewed Dreaming City.

For fans of Moorcock’s albino Eternal Champion, this is an adaptation that cannot be missed.

We have the blurb and a sneak peek into the first pages of the comic, below, thanks to publisher Titan Comics.

About Elric the NecromancerTwo years after the sack of the great city of Imrryr, Elric wanders across the land as a mercenary, still grieving the death of his beloved Cymoril.

But a new danger is not far away-Queen Yishana has a quest for the White Wolf, a journey into another dimension where elemental magic nor the enchantment of his mighty sword Stormbringer seems to function.

Without his powers, how will Elric face down the old threat that lingers there?

Variant coversTitan Comics have done a brilliant job bringing this cover to life with three other variant covers by (in order) Paolo Grella, Valentin Secher, and Pierre-Denis Goux.

I love the art style of Elric the Necromancer, with it’s dark, shady feel putting us right into the mood for a gritty, bloody adventure. Our experience reading Moorcock and Titan Comic’s reimagining of Dreaming City lets us know that these are the kinds of characters who play on the grey scales or morality, and will very likely appeal to our gridmark-loving crowd.

To find out what happens next in Elric the Necromancer, you’ll have to grab a copy, below!

Read Elric the Necromancer by Jean-Luc Cano and Julien BlondelYou can pre-order issue #1 from Titan directly, here, or gt a bundled issue #1 and Issue #2 below through Amazon.

The post EXCLUSIVE first look at Elric the Necromancer by Jean-Luc Cano and Julien Blondel appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 24, 2024

An Interview with O.O. Sangoyomi

O.O. Sangoyomi is set to dazzle the literary world with Masquerade in July. A story that is tender and slow just as much as it is dark and thrilling, the novel weaves historical West Africa with that of myth. The novel focuses on betrayal and politics, so it is a great fit for us at Grimdark Magazine. It was great to chat with her about debuting, complex relationships and power ahead of the book’s publication.

[GdM] Congratulations on your debut novel, Masquerade. Can you introduce Masquerade in a sentence or two for our readers?

[GdM] Congratulations on your debut novel, Masquerade. Can you introduce Masquerade in a sentence or two for our readers?

[OOS] Masquerade is a historical fiction novel in which a young Yorùbá woman climbs through the ranks of a Medieval West African warrior society. Loosely based on the myth of Persephone, the novel explores the cost of power and the lengths people will go to secure it.

[GdM] I’d love to know more about the inspiration for Masquerade. The story of Hades and Persephone for one, the Yoruba traditions another. How do you see yourself in the storytelling tradition(s)?

[OOS] I wrote Masquerade my sophomore year of college. It stemmed from my frustration about being unable to find classes related to Africa at my school, especially classes about pre-colonial Africa. I was born to Nigerian immigrants, so I’m passionate about the history of West Africa in particular. That interest inspired me to research Medieval West Africa in my own time. The more that I read about the richness of this historical era, the more inspired I became to write a story set within this time period. Especially because storytelling plays such an important role in Yorùbá culture in terms of preserving histories and memories, it was important to me to try fighting against the kind of death that comes when a culture or a history is no longer talked about.

[GdM] Can you talk a bit about the blacksmiths and why they occupy such a focal position in Masquerade?

[OOS] In Yorùbá culture, artisans are held in very high esteem. Not just blacksmiths, but also sculptors, weavers, carvers. In general, the act of creation is a revered endeavor. In regards to blacksmithing, that profession has always held a particular place of fascination in the imagination of the Yorùbá people. For a long time, the technicalities of blacksmithing were kept secret from the general public, making blacksmiths their own kind of closed guild. And because no one knew how they transformed metal, many people believed that the process was magical.

Historically, Yorùbá blacksmiths were men, and because of their abilities, they were highly respected in society. In Masquerade, I reimagined this position as one that is instead occupied by women. I wondered, if the same, seemingly mystical abilities of a blacksmith were in the hands of women, would it be as positively received? Probably not. Throughout history, witch-hunts have occurred in many parts of the world to whatever degree. They all derived from the same thing: the majority group in a society believing the minority group was becoming too powerful, and fearing how that power might be used against them. So it made sense to me that a group of women on whose abilities the empire is dependent would be highly resented.

[GdM] Òdòdó goes through a lot in Masquerade. Throughout, her resilience and cunning stand out. What do you hope the reader takes from her?

[OOS] Unlike most strong female protagonists, Òdódó has neither a fierce personality nor does she blatantly speak her mind. She tends to keep her cards close to her chest, and because of her quieter disposition, most characters who meet Òdódó in the book do not think much of her. Òdódó is aware of how people regard her, and she learns to use this against them. She does things like asking intrusive questions while knowing she can get away with it because no one believes her smart enough to use the information, and she is not afraid to lean into her perceived naivety if it helps her avoid suspicion. She is a fast learner, but she does not let on to just how much she has learned, and her enemies do not realize what a formidable opponent they have created in her until it is too late. So, if readers take anything from her, it can be that there is power to be had in being underestimated.

[GdM] I particularly enjoyed Òdòdó’s complicated relationships with her mother, as well as with the twins. What drew you to focus on these imbalances of power?

[OOS] A common theme in Masquerade is that of convoluted love. Òdódó has a complicated relationship with the king she is being forced to marry, but she also has a complicated relationship with her mother. I think the manner in which people love tends to be the same with how they conduct themselves in every other aspect of their lives. So, as a pessimistic and brutally honest person, Òdódó’s mother cannot help but love Òdódó in a way that seems quite negative and almost more like hatred. It was interesting to explore the concept of a love that, as twisted as it is, is at the same time deep and genuine.

The twins’ role in Masquerade was also interesting to explore. Throughout the novel, in order to get what she wants, Òdódó leans more and more into the strengths that women have and that men do not. She then takes that a step further by also including children in her schemes—which is another group that, like women, tend to have their intelligence and skills be overlooked. It is a mark of Òdódó’s patience and determination that she learns how to utilize the small but unique access that women and children each have to certain facets of life. Over time that gradual collection of power accumulates into a greater one that cannot be challenged, and it is all built on the strengths of underestimated groups.

[GdM] Can you talk a bit about your approach to disability and prosthetics in the story and how it connects to power?

[OOS] In the book, Òdódó is surrounded by powerful men who have, for the most part, obtained their repute through war. Because that is the most overt display of power, at first it seems that if Òdódó is to have any power herself, she must learn to fight like a man. But after Òdódó barely survives a situation that leaves her disabled, she begins to lean into methods of power other than physical fighting. She learns how to filter through gossip for valuable information, how to manipulate others with just her words, and how to use her beauty to win allies. In other words, she uses tactics that are typically dismissed or overlooked by men, but that end up getting her much further than brute strength would have. So ultimately, Òdódó learns that she does not need to learn how to fight like a man; it is much better to fight like a woman.

[GdM] Following on from that, I felt like the loneliness of power, the segregation it brings with it, was core to Masquerade. I’d love to hear more about your intentions in this regard.

[OOS] When Òdódó first arrives at the king’s residence, she is enchanted by the life of luxury that is to be found there. She takes everything in, not just the sights but the people as well, accepting every offer of friendship that comes her way. But what Òdódó learns the hard way is that she has just entered a world in which everyone has their own motives, and to them, Òdódó’s arrival is nothing more than a new opportunity to use her in advancing their individual plans. Throughout the novel, as Òdódó faces betrayal in different ways, she comes to realize that if she is going to make it to the top of the social ladder, she is going to have to play the same games that everyone else does. She learns that she can only put her faith in people, not based on friendship, but based on a partnership that is mutually beneficial. Ultimately, Òdódó comes to have a handful of people in her circle, but none whom she allows herself to trust implicitly again, and that is the sacrifice she makes to hold onto her power.

[GdM] One thing I particularly enjoyed about Masquerade is how the story dares to be slow. A lot happens, but to me, it felt like characters had time to develop rather than jumping from action to action. Was this a deliberate choice?

[OOS] Immersion was a priority for me while writing Masquerade. Especially because this is a time period with which many readers will likely be unfamiliar, it was important to me to paint a vivid picture of the richness this region of the world has had. Careful detail was paid toward building the setting, but also toward building the plot. In order to create a tension that only increases as the book goes on, the groundwork for multiple pieces needed to be firmly established and have room to develop. That way, when it all comes together at the end, it can do so at a fever pitch.

[GdM] With Masquerade so grounded in history, you must have done a lot of research. Can you talk about about the process and the challenges?

[OOS] In order to construct the world of Masquerade, I drew from the three most notable empires of Medieval West Africa: the Mali Empire, the Songhai Empire, and the Kingdom of Ghana. Elements of the Ọ̀yọ́ empire and Yorùbá history in general are also woven into the story. In terms of my approach to this, I would start out with a specific topic, such as the gold trade in 15th century West Africa, then branch out into similar topics from there. I read a number of sources, ranging from history books to written accounts by European explorers who visited the region at that time, and I was also able to speak with Nigerian scholars who could elaborate on aspects of Yorùbá culture.

Undoubtedly, the most frustrating part of my research process was the sheer lack of sources available about pre-colonial Africa. For every one source I was able to find, there were ten more available for a different part of the world during the same time period. And it does not escape me that, of what little information there is available, most of it comes from the pens of Europeans. It is devastating to think about how many details have been destroyed because a group of people have been prevented from preserving their own history.

[GdM] Do you have any (book) recommendations for readers who need to get over the emotional hangover caused by finishing Masquerade?

[OOS] For more historical fiction: The Mayor of Maxwell Street by Avery Cunningham or The Monsters We Defy by Leslye Penelope. For more feminist journeys that incorporate mythology: Kaikeyi by Vaishnavi Patel or Daughter of Fire by Sofia Robleda. For more stories rooted in West African culture: Raybearer by Jordan Ifueko or The Gilded Ones by Namina Forna.

Read Masquerade by O.O. SangoyomiThe post An Interview with O.O. Sangoyomi appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 23, 2024

REVIEW: When the Moon Hatched by Sarah A. Parker

When the Moon Hatched grew a passionate following on TikTok when it originally launched earlier in the year. It resonated so well with audiences that HarperVoyager UK and Avon US snapped it up immediately – and now When the Moon Hatched is getting a re-birth across the globe. Deservedly so, it is compelling, dark and most of all, fun to read. I love how dragons are having a moment – this is the third dragon book I’m covering for Grimdark Magazine this year and I’m here for them all.

Raeve is an assassin for the rebellion… And we meet her just as she loses everything. Her friend, dead, her captured by the Guild of Nobles – powerful fae. It wouldn’t be a good novel if the story ended there, though. She soon meets Kaan, a brokenhearted dragon rider and together they find truths that might unravel everything they know about the world and themselves. The story is interspersed with diary entries from a long gone woman’s childhood and youth. When the Moon Hatched doesn’t do anything revolutionary with plot or characters, nevertheless, it is a very compelling and fast-moving story with a focus on characters.

Raeve is an assassin for the rebellion… And we meet her just as she loses everything. Her friend, dead, her captured by the Guild of Nobles – powerful fae. It wouldn’t be a good novel if the story ended there, though. She soon meets Kaan, a brokenhearted dragon rider and together they find truths that might unravel everything they know about the world and themselves. The story is interspersed with diary entries from a long gone woman’s childhood and youth. When the Moon Hatched doesn’t do anything revolutionary with plot or characters, nevertheless, it is a very compelling and fast-moving story with a focus on characters.

When the Moon Hatched does well balancing hints with reveals, keeping the reader in the dark for much of the story. And I loved how the title ended up being quite literal. Raeve knows exactly who she is at the start of the story … as the book goes on, she loses that grounding in her identity and we spend most of the story with her trying to reconcile “should” with “be”, finding herself again. It is surprisingly un-spicy for Romantasy, which I found to be a great plus, focusing on relationships and emotional growth over carnal desire. This might not work for everyone, but it did for me.

Looking at When the Moon Hatched from a grimdark perspective, there is much the reader will appreciate. We start out with death and betrayal, follow an assassin and revolutionary and go on to destroy and rebuild her world again and again in a metaphorical sense. The setting takes a lot of inspiration from the Romans – complete with a coliseum where convicts are executed via dragon. The story is dark, the characters constantly juggling and re-evaluating their morals and fighting for a future less fraught than the status quo.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the beautiful chapter header illustrations. As far as I’m aware these are kept in every edition. Well-designed books (and illustrations) tend to get me swooning and this was no different. They illustrate the book really well and just made me very happy every time I came across one while reading – while they’re not narrative, they help round off the reading experience. I enjoyed When the Moon Hatched greatly as a popcorn read and am looking forward to seeing how it’ll impact the genre.

Read When the Moon Hatched by Sarah A. ParkerThe post REVIEW: When the Moon Hatched by Sarah A. Parker appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 22, 2024

REVIEW: Ninth Life by Stark Holborn

Last Updated on June 23, 2024

Gabriella Ortiz has worn and shed many names. Tales of her exploits transcend time and space, defying reality. Depending on which name, she is a hero of both sides. A felon with a bounty on her head worth twenty million. Ortiz has been officially declared dead a handful of times and, in some realities, died almost twice that amount. Her next death will be her last. Her last alias will be remembered by all. Ninth Life by Stark Holborn is a compilation of myths, the unofficial story of a legend.

The Factus Sequence trilogy spans a hundred years of history regarding the moon of Factus and its war with the Accord. It begins with an Ex-convict medic dubbed Ten Low discovering a crashed spaceship and rescuing Gabriella Ortiz. Ten Low soon realizes Ortiz is not an innocent child, but a genetically enhanced super soldier. Once the Accord’s greatest achievement and pride, it seems these soldiers were betrayed. They are being hunted for elimination. What originated as a mission to save Ortiz starts the threads of destiny. The transpiring events and their actions will define the fate of Factus. Stark Holborn concludes this epic space adventure in Ninth Life.

The Factus Sequence trilogy spans a hundred years of history regarding the moon of Factus and its war with the Accord. It begins with an Ex-convict medic dubbed Ten Low discovering a crashed spaceship and rescuing Gabriella Ortiz. Ten Low soon realizes Ortiz is not an innocent child, but a genetically enhanced super soldier. Once the Accord’s greatest achievement and pride, it seems these soldiers were betrayed. They are being hunted for elimination. What originated as a mission to save Ortiz starts the threads of destiny. The transpiring events and their actions will define the fate of Factus. Stark Holborn concludes this epic space adventure in Ninth Life.

Stark Holborn shakes up the narrative in the final novel of The Factus Sequence trilogy. While Ten Low and Hel’s Eight are primarily told from Ten’s point of view, Ninth Life celebrates Garbriella Ortiz. This is a surprising and necessary turn in perspective. The character readers know as Ten Low would not exist without Ortiz. Their lives intwine. They are pivotal players in the rebellion against the Accord. Together, they shape the future of Factus.

Ninth Life is told from a dossier by military Proctor Idrisi Blake. As a professional, Blake is tasked with compiling all information regarding Gabriella Ortiz, her aliases, and every life she has lived. A task made impossible by all the conspiracies and cover ups surrounding this legend. Blake’s dossier mainly consists of recordings left by a new character Havemercy Grey and is supported by other testimonies and interviews.

Stark Holborn takes a risk with changing the primary point of view in Ninth Life and succeeds. While Ninth Life is a secondary account of Gabriella Ortiz’s life, the characters involved are bursting with personality. They develop like any other well written main characters. Due to the nature of Stark Holborn’s world, telling Ortiz’s life through different accounts is the truest approach. This dossier is compiled of unverifiable information and tall tales. The half truths offered by alternate realities blending together.

Even well-read science fiction fans will find much to be excited about in The Factus Sequence trilogy. The compelling characters are rivaled by an equally fascinating world. The moon of Factus is a savage wasteland ruled by possibility. While its inhabitants hold no respect for the Accord, all know to fear the chaotic power present there. Little is understood about this divine force or reality splitting phenomenon. Stark Holborn expands the worldbuilding in Ninth Life, revealing more about the mysterious power on Factus and the other worlds in this universe.

Stark Holborn writes an extraordinary conclusion to The Factus Sequence trilogy. Ninth Life is an explosion of action and imagination. This epic finale takes risks and, in doing so, honors its amazing characters and world.

Read Ninth Life by Stark HolbornThe post REVIEW: Ninth Life by Stark Holborn appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 21, 2024

REVIEW: Gates of Sorrow by J.E. Hannaford

Gates of Sorrow, the second volume in J.E. Hannaford’s epic fantasy series, Aulirean Gates, picks up immediately following the dramatic conclusion of Gates of Hope. Since I don’t want to ruin the fun for readers who haven’t yet started this series, I will keep my review completely spoiler-free for both books.

Gates of Sorrow is set on the planet Lieus and its two moons, Mythos and Tebein. The three bodies, collectively known as the Aulirean System, were connected by magical portals allowing for easy transportation. However, in the opening prologue of Gates of Hope, the gates are destroyed by a giant space dragon known as the Watcher, presumably to end a brutal war.

Gates of Sorrow is set on the planet Lieus and its two moons, Mythos and Tebein. The three bodies, collectively known as the Aulirean System, were connected by magical portals allowing for easy transportation. However, in the opening prologue of Gates of Hope, the gates are destroyed by a giant space dragon known as the Watcher, presumably to end a brutal war.

J.E. Hannaford achieves a Brandon Sanderson level worldbuilding in the Aulirean Gates series. Like its predecessor, Gates of Sorrow imbues a continual sense of wonder as we learn more about the story’s universe and magic system. All of this is revealed in a natural fashion, without any awkward info dumps.

One of my favorite parts of Gates of Sorrow is exploring the larger moon of Mythos, which is home to the Watcher and a community of dragons that encapsulate different types of emotion. Mythos is very different from the smaller outer moon of Tebein, which had been colonized by humans who became stranded once the gates were destroyed and struggle to survive in the shadow of a hostile alien race known as the awldrin.

Meanwhile, the planet of Lieus has experienced a dramatic event known as the Rending, which left its main continent of Caldera covered with deep craters. Most people live in communities within the craters, avoiding the unsafe upper surface of the continent. The eastern part of Caldera known as the Edgelands is especially dangerous, home to fearsome beasts that migrated from the planet’s two moons prior to the gates’ destruction.

While I’m emphasizing J.E. Hannaford’s outstanding worldbuilding, Gates of Sorrow is primarily a character-driven novel with three point-of-view characters. Darin is a young man from Caldera who bonds with a moonhound named Star. Moonhounds are large shaggy dogs who use doggie dream magic to select a human for bonding. Darin and Star have a telepathic bond enabling them to share images with each other. Darin’s story finds him going deeper into a secretive society while learning to control his own magical powers to help Suriin, the second main character.

Suriin is a teenaged girl whose lilac-colored hair provides a visible indication of her magical powers. In Gates of Sorrow, Suriin must deal with the aftermath of misplaced trust, which has implications for both Suriin’s life and the fate of everyone on Caldera.

My favorite point-of-view character in Gates of Sorrow is Elissa, a young woman living on the outer moon of Tebein who is labeled as “Untouched” and targeted by the awldrin for her lilac-colored hair. When the shard of a magical crystal becomes embedded in her foot, Elissa may provide the only path toward salvation for the stranded population of Tebein. While all three main characters experience satisfying growth in Gates of Sorrow, Elissa really goes to the next level through her interactions with dragons. (That’s her riding a dragon on the cover!)

J.E. Hannaford’s writing is refined and accessible, a delight in every way. Grimdark readers will appreciate Hannaford’s nuanced characterization and complex worldbuilding in Gates of Sorrow, which offers great re-readability for readers like me who simply cannot get enough. Altogether, the Aulirean Gates proves to be one of the most compelling new epic fantasy series in recent memory.

Read Gates of Sorrow by J.E. HannafordThe post REVIEW: Gates of Sorrow by J.E. Hannaford appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

Read on Amazon

Read on Amazon Read on Amazon

Read on Amazon