Michael W. Twitty's Blog, page 13

March 9, 2016

Tracing Family Roots Through Food With Michael Twitty – The Kojo Nnamdi Show

https://thekojonnamdishow.org/shows/2016-03-09/tracing-family-roots-through-food-with-michael-twitty

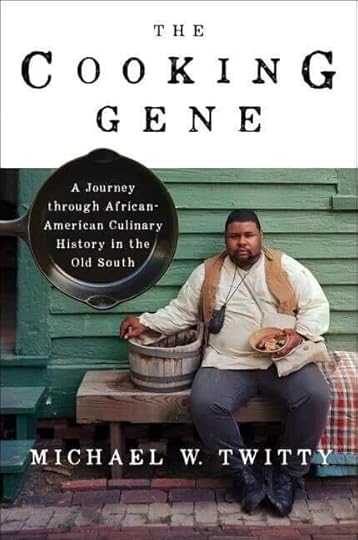

I had a great time today with the one and only Kojo Nnamdi of DC’s NPR affiliate, WAMU 88.5. We discussed my new forthcoming book The Cooking Gene on his renowned program where Wednesdays are food days! We talked food, genealogy, genetics, faith, family, and recipes. Have a listen and be sure to contribute to your local NPR affiliate!

The Cooking Gene available for pre-order here!

March 3, 2016

#WorldBookDay Pre-Order The Cooking Gene today

On November 8, 2016, HarperCollins will release my first book: The Cooking Gene: A Journey through African American Culinary History in the Old South.

RACE. We are fascinated by it and imprisoned by it, frustrated by it and endlessly debating its meaning. Since 1492, few issues have complicated the human journey like the way we have braided categories of color, character, creed and class into the illusion of “race.” We are weary and we need a way into more constructive dialogue and world-changing action.

FOOD. We are fascinated and imprisoned by it, frustrated by it and endlessly debating how it should function in our lives, culture and personal identities. We have braided our feelings about culture, history, race, class, gender, health and sexuality into the reality of food. Waves of human migration, innovation and cultural collisions have created a global food culture where regional food identities are capital in the marketplace of ideas.

FAMILY. We are fascinated by genealogy and genetics, imprisoned by our upbringing, frustrated by our heritage and the shortcomings of our kin, and endlessly recounting the importance of family—blood and otherwise—in our lives. It’s hard for us to see ourselves outside of the nexus of family and even harder for us to embrace the idea of the human family. And yet, the meaning of family and kinfolk is elastic—and we can find family where we least expect it.

In the 1760’s and 1770’s my direct paternal and maternal ancestors arrived here at Sullivan’s Island near Charleston, South Carolina from Sengal, Sierra Leone, Ghana and Angola.

In 2011, I started planning a never-ending journey to finally answer nagging questions—“What are my roots and where do I come from? How does all of it impact my work as a food writer, a culinary historian and a historic interpreter who educates people about America’s second original sin—the enslavement and oppression of Africans and their descendants? And how does food tell the story of my family and my people-from Africa to America and from slavery to freedom?”

Me at 3 with the Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary on a Fisher-Price Table–You can’t see it but my toy stove and cooking set is in the background…

I set out on the roads of the Old South to look for places of cultural memory and culinary importance—fields, towns, coasts, swamps—where cooks—both enslaved and free people of color stirred the pot that became Southern food. I began taking a series of genetic tests—each one peeling back the layers of time to reveal what the records I pored through could not—my Old World origins and place among the wider Southern family. I talked to elders, planted seeds with children, visited farms and battlefields and cooked in kitchens where I saw tears, ghosts and realizations…

With Dr. Henry Louis Gates wrapping up taping of part of Many Rivers to Cross

Not the least of which was that I was inextricably connected to a bigger family than I had ever dreamed possible.

This book is part food memoir, part genealogical and genetic detective story, and a love letter to the culinary story of my Ancestors and their food-steps across the Southern landscape—from their arrival in chains to their day of liberation and Jubilee. Ten years ago I set out to become the first antebellum chef in 150 years—bringing the historic traditional foodways of the South back to life. Now I set myself to the task of telling my story and my family’s story through food—exploring every angle of our American journey through the meals, ingredients, flavors and delicacies that defined our dynamic, ever changing identities that lead to this moment, now.

Cymlings and Okra in Mississippi at an African American run farmer’s market

To do this I ate dirt–specifically–I sucked on red clay. I picked cotton and primed tobacco, plucked rice and cut cane. I shared a drink with Confederate army re-enactors and cooked at Southern synagogues. I met a 101 year old man who was born in the days of Jim Crow but lived to see and vote in 2008 and 2012. I cooked meals alongside black and white and Native and Asian and Latino chefs searching to understand their role in the flow of Southern history and culture. I met kinfolk of all colors and my family—blood and bone and kindred spirits—became wide—from Ghana to England to Sierra Leone to Alabama to Canada to the ends of the world. I searched for culinary justice and opportunities for uplift using food, farming and tradition to improve our lives. And I ate.

This journey is not about kumbayah—it’s centered in confrontation and digging for the truth. And yet, our confrontation takes place at the table of brotherhood. This book is an account of me confronting the illusion of race and the reality of food. This work is about confronting history, confronting my heritage and its misrepresentations, confronting my health, my future, my family and my pre-conceived notions. This is an account of my confrontation and conversation with my region, my nation, and with Southern whites—my cousins rather than combatants—and in all of it–food is the vehicle.

Dialogue with Hugh Acheson at Stagville Plantation, North Carolina

I don’t know if what you’ll be reading in November will change your lives. However I hope it starts a conversation of how we got here and where we need to go and how we can help each other on the way. It is first and foremost a love letter to my people and my country on the eve of our 400th un-official anniversary as a people born in pain raised to an uneasy triumph. It is second, a message of reconciliation and healing to the Southern family in a time when we desperately need it on a national and regional level. It is third an offering to my Ancestors—from the kingdoms and villages of West and Central Africa to the kitchens high and low across her Diaspora where a great cuisine was forged in chains. And lastly it is a prayer for our humanity and the hope we can sit as a global family at the feast of peace.

Here’s how you can pre-order your copy today: For Amazon click here. For links to HarperCollins, Barnes and Noble, Indie Bound, Powell’s etc. click here.

March 2, 2016

Outsourcses: Setting the Table with Michael Twitty – Food, History, and Sexual Identity in the South | KGNU News

I have rarely had the opportunity to do in person radio interviews that significantly involve or incorporate my identity as an openly gay man and discuss how lgbt issues impact my work. Well, here she goes! I sat down with Sean Kenney after a fantastic night of feasting and discourse at the University of Colorado in Boulder to discuss the intersections of my personal identity and my work. I am very impressed by Brother Sean’s interviewing skills–he touched on so many salient issues and made me feel at home in my mind. I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did!

February 16, 2016

Washington Post Food Section Profile

I just wanted to share with everyone this fantastic food section profile by Michaele Weissman on the growth of my work. It says a lot about how I got here and what keeps me here. I want to thank Michaele, Joe Yonan, and Bonnie Benwick *THERE ARE RECIPES!!!!!* for all they put into this story and for letting my home town–Washington DC—know more about a local kid. I hope this piece inspires our young people. I don’t want to be the only one…I want new farmers, new cooks, new dreamers and learners!

Thank you. I’m just grateful. Very grateful. So are my Ancestors. Coming on the heels of my talk yesterday at #TED2016 I am absolutely in tears of joy.

February 15, 2016

Where Food and History Meet: Michael W. Twitty’s Culinary Journey at Afroculinaria | Discover

https://discover.wordpress.com/2016/02/15/afroculinaria/

Hi! I’m waving from Vancouver, Canada where I’m sooo excited to be attending #TED2016 as a new Ted Fellow. If you’re learning about my work for the first time, the above profile link (Thanks Cheri/WordPress!) will catch you up to speed.

If you’re at #TED2016 please come up and say hello! Come join me and my incredibly talented class of Fellows at our talk today!

January 19, 2016

Taking the Cake

So there is a lot of press about two children’s books published as of late. One, A Fine Dessert, was published and honored, another, A Birthday Cake for George Washington just got pulled. Both showed smiling enslaved cooks serving their wealthy planter slaveholders. People sounded off. I had to add my voice to the discussion. In one piece for Salon I am quoted, and in another, I write about the thorny nature of slavery in both national memory and children’s books in the Guardian. Let me know your thoughts on the subject.

Happy slaves or a wider lens? You decide. I have no interest in the pontificating on the part of the Twiterati/Newgrorati. Nope. Not until they do this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

January 16, 2016

A Letter to the Newgrorati: Of Collards and Amnesia

Dear Newgrorati on #BlackTwitter,

If you want to learn about a culture, listen to the stories. And if you want to change a culture, change the stories.—Michael Margolis

We need to have a talk about collard greens. Like, now.

Apparently some – y’all thought Whole Foods was punking you with “new-fangled” recipes and a stock pic of collards with peanuts. Y’all went off and went deep. Think again.

We can’t get cemented in stereotypes about our food culture. Our tradition is so old and so broad it deserves more respect than lazy assumptions and not being informed. Let’s go deep…read this….

Oh yeah….greens in peanut sauce and greens with peanuts. Guess what…we were still doing that in the Deep South in slavery time…we kept seasoning and flavoring our greens with sesame and peanuts and salt fish well into the early 20th century. Why don’t you know about that? Easy..these traditional preparations became less and less popular as we moved further away from the generations born in Africa. I.E., the more acculturated we became the further we moved from some of our healthiest foods…its a cultural tragedy in the age of massive chronic illness among African American folk, my family included.

Let’s talk about collard history though my Newgroes, because we need to break this down…

The collard’s complicated story with African Americans really speaks to the way food can unravel the mysteries of complex identities. In 1781, Captain William Feltman of the Continental Army gave the first documentation available thus far linking Black folks in the Southern U.S. with the collard as he traveled through Hanover County, Virginia: “The Negroes here raise great quantities of snaps and collerds

(sic) they have no cabbages here.”

Ezra Adams—South Carolina—formerly enslaved said:

“If you wants to know what I thinks is de best vittles, I’se gwine to be obliged to (admit) dat is is cabbage sprouts in de spring, and it is collard greens after frost has struck….I lak to eat.”

Background History

Collards (Brassica oleracea acephala) are not African, they are temperate and Eurasian in origin, but their consumption, and with them—turnip, kale, rape, mustard and other greens are a healthy blend of tastes—West and Central African, Scottish, Portuguese, German and the like. Many culinary historians agree that the green craze in the South is supported by tastes for spring greens among Celtic and Germanic Southerners but was really spearheaded by people of African descent. In tropical West Africa, greens were available year round in gardens and markets and figured prominently

in regular meals. Unlike Northern Europeans, West and Central Africans had a climate that supported a continuous variety of edible greens from both cultivated and wild plants. Amaranth, celosia, inine (African spinach), and the leaves of cowpeas, cassava, okra, sweet potatoes, and other vegetables helped make up the 30-60 edible leaves prepared during the age of the slave trade. Long before America there were varieties of plants botanically cognate to chenopodiums and phytolacca (read lambs quarter and poke) in West Africa. Often referred to as “relish,” these African greens were made into a sauce to be eaten with rice, fufu or millet and some groups associated them with sacred medicine and vitality.

At some point in the Middle Ages, cabbages and turnips diffused south to what is now Mali from Morocco to feed Moroccan salt traders and scholars visiting Timbuktu. While the first generation arrival of these plants was not said to spread out of the Moroccan quarter, these vegetables are still grown in the Sahel today as valuable market crops. As early slave forts sprung up via the Portuguese trade, so did gardens to supply their dietary needs. Cabbages and turnips enjoyed only measured success and usually depended on microclimate conditions that allowed for cooler breezes and night temperatures. Kale and colewort (get it? “collard” comes from colewort —chou vert/couve/cole) were frequently mentioned in letters and records of slave forts and their gardens. You better believe these seeds and plants left the shelter of the forts and began making their way into the interior of what is now Ghana, Angola, Senegal and Nigeria.

Meanwhile African culture was happily eating greens gathered from the wild, the garden and from trees. In Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of the pre-colonial Igbo world, Things Fall Apart, Ezinma, the charmed daughter of the main character, Okonkwo prepares “green vegetable” with her mother, noting a folktale where the greens shrink down and cause a catastrophe as a cautionary tale to pick as many greens as are necessary to feed one’s guests.

African and European tastes converged with greens “seasoned” with a bit of meat or salt fish and highly peppered merged with Portuguese caldo verde (greens soup, traditionally seasoned with linguica—or Portuguese cured meat/sausage) and later obtained the spiky taste of the capsicums—the New World “peppers.” At least one reference refers to Africans adopting the European’s “cabbage soup,” noting that the elites enjoyed more meat with it and that it was highly seasoned with hot peppers. In Brazil, couve or collards are a staple in the Black diet, and are a classic accompaniment to feijoada, the national dish of Brazil…a blend of African, European and Amerindian influences all under the umbrella of Afro-Brazilian spirituality…since it is a favorite dish of Ogum/Ogun, the Orisha of iron, war and meat.

Back to Hanover County, Virginia and beyond… Collards were not raised everywhere nor were they necessarily endemic to the South. Coleworts were “sprout” greens…eaten while tender and non-heading, and as the descendant of kale and cabbage, the collard could be raised into the mild Southern winter where it sweetened under successive frosts and provided greens despite the season. It is highly possible that the first Africans in Virginia, being Afri-Creoles from Portuguese Angola (where peanuts are in everything) (nguba=goobers) would have known the colewort and appreciated it’s cultivation by their 17th century English captors. The collard was in gardens both high and low, but their popularity was certainly encouraged by the presence of greens-loving cooks of African descent. Some commentators described enslaved people’s quarters crowded with collard patches. They were raised at Monticello and sold to the Jefferson family as well as cultivated from time to time in Jefferson’s experimental gardens. “Sprouts” included a whole family of leafy non-heading greens but the colewort was chief among them:

Lettice Bryan’s Sprout (Read Collard) Recipe, The Kentucky Housewife 1839

Should be boiled in every respect like turnip salad, served warm with bacon, and seasoned at table with salt, pepper, and vinegar. All kinds of salad should b thoroughly washed in two waters, otherwise it will be gritty.

Remember that ritual your mother used to do of washing and cutting the greens? That’s ancient stuff.

Green Glaze Collards

The variety you see in the picture above is my personal favorite, Green Glaze. They are pretty, waxy, crisp, tough against bugs and extremely delicious. They also happen to be the oldest variety we have/know of collard green dating back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with the Georgia Southern or Creole collard out of the Deep South going back to the 1860s-1880s.

Slave Food: The problem with being Collard People

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad meant well when he wrote Eat to Live, in fact he presaged a host of health problems in the Black community and their larger detriment to the health and economy of African American communities. However, he had a few bumps on the way including collards unfit for human consumption. Actually, cowpeas, sweet potatoes, collards, kale, red peppers, onions, string beans and the like are fantastic natural foods. Our ancestors ate Superfoods! Their role in preserving and benefiting the enslaved person’s diet—and the diet of those right out of Emancipation was widely noted:

“To the inhabitants of the country districts of the South, the collard is a very great blessing; because when boiled in a pot with a piece of fat meat and balls of cornmeal dough, having the size and appearance of ordinary white turnips, called dumplings, it makes palatable a diet which would otherwise be all but intolerable.” James Patterson Green, North Carolina.

This food connects us to the globe. It connects us to Africa. It connects us to slavery, to freedom, to sharecropping, to migration, to triumph, to survival. It’s a powerful symbol of our history, our social identity, and the cuktural politics we negotiate our lives by.

We don’t mind cultural diffusion. That’s a natural and important consequence of being human and living in community with other humans. However the “collard is the new kale,”/”ooh look whole animal cooking”/wow isn’t this food so barnyard tasting..” that’s got to end. I don’t think that’s what WF was going for, but we’ve seen it so much it’s untenable and it drives us crazy. You don’t have to be Jewish to eat Levy’s Rye, and you don’t have to be “Colored” to love collards, but this is the key….being culturally aware needs to be a value in our society–for all of us. We need to revisit this collard thing next January when cooler heads prevail, I’ll be happy to give you some reading material.

January 13, 2016

Haven’t You Heard?!

December 30, 2015

A New Way With New Years Day/African Black Eyed Pea Salsa

I went to Whole Foods last night.

I actually bought a container of pre-soaked black eyed peas. Yes I did!

I am not going to be stewing over some stove just because I can get me a lil “change,” and good luck in 2016.

Naw, boo. I’m making a change in how I do New Years. So just in time for you to do the same I offer you an alternative without totally re-inventing the wheel.

So I got to thinking about New Year’s as a time to eat . Does it have to be a completely heavy meal or can it be a sampling of things, like Afrocentric tapas or mezze. New Year’s also coincides with the day of the karamu or Kwanzaa feast on the day of Imani, or faith.

Let’s keep it simple…sorta 7 or 14 foods–your choice–representing every corner of the African world. Yes there’s a recipe coming but I’m stalling…

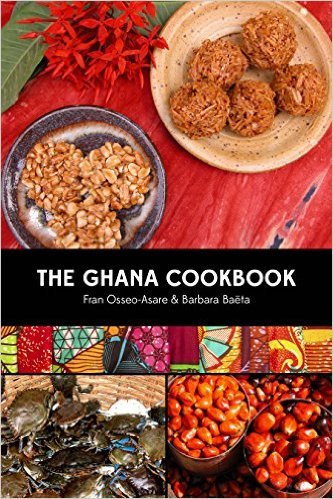

Rice and peas or beans of some sort. Or just rice. Or millet. Or fonio. Or grits :) But really, you need some Jollof Rice in your life and here is the place to find it–The Ghana Cookbook.

If meat is your thing-and it is certainly mine, you need some lamb, goat, mutton, beef or chicken in your life.

I love Pierre Thiam’s recipes. Click here for something great starters from Pierre. His roast lamb in his new cookbook with tamarind barbecue sauce is over the top fantastic. I am hoping to raise enough money to make it to Senegal this year so I can try some for myself.

3. Fish or Seafood. For those you need to visit Ms. Dora Charles. This is hands down my favorite traditonal soul food cookbook of the year. Her fried fish or shrimp and grits or shrimp gumbo will fill the need for the something wonderful from the sea.

4. Want traditional and reliable? Go with the authentic and encyclopedic Southern Soups and Stews by Nancie McDermott for classic recipes for collards with dumplings and stewed black eyed peas. This is a keeper.

5. Smoked Trout Deviled Eggs, yes I said it. 2015’s most innovative and fresh approach comes from the beautiful Nicole Taylor with her The UpSouth Cookbook.

6. Searching for healthy alternatives to traditonal recipes that still come from tradition? Look no further than Team Randall. Soul Food Love is exactly what you’re looking for.

7. So I want to make collard chips. No I don’t have a recipe because I’ve never done it before but I’m going to try and I found an awesome recipe for them: Try this one from the blog The Inspired RD. Alysa Bajenaru–thank you for this healthy alternative snack and a break away from the kale jail.

8. Ok, Finally that recipe….African Style Black Eyed Pea Salsa

1 can of black eyed peas or field peas, drained—get a brand you trust to be reliably firm and not mushy

2 cups of chopped ripe, juicy tomato–or as best you can find.

1 cup of finely chopped bell peppers–green, yellow and red.

1/2 cup of minced red onion

2 tablespoons of minced fresh garlic

1 tablespoon of vinegar (I prefer apple cider vinegar)

2 tablespoons of chopped up preserved lemon

1 teaspoon or more to taste of coconut sugar or turbinado sugar

1/2 teaspoon of kosher salt

1/4-1/2 teaspoon of red pepper flakes according to taste

1/4-1/2 teaspoon of black pepper according to taste

1 teaspoon of harissa seasoning. (North African spice mixture)

1/2-1 teaspoon of hot sauce –preferably peri peri sauce from South Africa.

Mix all ingredients together and chill for a few hours before serving. Stir to combine flavors every now and then.

9. Going Vegan or Veggie? I still have to make that Bryant Terry plug because not enough people know about this book—it should be a household staple!!!

10. Cook to impress—-if you want updated Southern classics with a classic French cuisine technical flare—then go with my homegirl Jennifer Booker. Field Peas to Fois Gras–its all there and its all good. and its fancy but not fussy.

11. If you need a last minute Kwanzaa gift–baby–have I got one for you and it has a good number of recipes from across the entirety of African American culinary history including forays into the Diaspora and the Continent–and its the closest thing we have to a family album of African American culinary literature! This is IT. IN my opinion the most important book EVER written about the culinary history of African Americans–and I want a sequel. Toni Tipton Martin’s The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code.

12. Now for the sweet tooth. We have a new African American dessert classic: Grandbaby Cakes by Jocelyn Delk Adams who also has a very popular blog.

13. Sweet potato chips make an excellent dip for that salsa–besides you need something that looks like “gold coins.” Here is a great recipe and demo!

14. What’s New Year’s without a cocktail. My favorite mixologist is Tiffanie Barriere from Atlanta. Here is a delicious delicious cocktail that will put some pep in your step!

Who am I kidding, I never really keep it simple.

Happy Cooking and Happy New Year 2016! Don’t forget The Cooking Gene in 2016!

December 25, 2015

American slaves’ Christmas was a respite from bondage – and a reinforcement of it | Michael W Twitty | Opinion | The Guardian

I wish everyone a happy holiday. It’s interesting that for such a straight, matter of fact piece, the first comment was already negative and had to be removed by the Administrator. I never thought that in 2015, even writing about African American history would get immediate hate mail. Yes Virginia, even the enslaved had a “Christmas,” and it had a lot of different meanings for enslaved people. It is important to not forget what that life was like for them and how that we world impacted us today. I proudly and defiantly write their story because it must must must be told. Merry Christmas! Please share this information at your holiday table, social justice is an enduring holiday message.

The original re-creation of John Canoe at Somerset Place Plantation in Creswell, NC.

Michael W. Twitty's Blog

- Michael W. Twitty's profile

- 322 followers