Jay L. Wile's Blog, page 42

January 21, 2016

Using Pigeons to Diagnose Cancer?

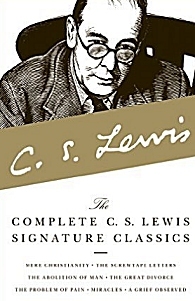

Dr. Pigeon examines a microscope image of tissue to see if it is cancerous.

(image from the article being discussed)

Pigeons are surprisingly smart birds. Quite a while ago, I wrote about how pigeons can learn to solve probability problems better than some people. In addition, homing pigeons can use sound to find their way back home. Now here’s a new way of looking at the intelligence of pigeons: they can use their pattern-recognition abilities to find cancer in microscopic images of tissue!

In the study, researchers put 16 pigeons in a box with a computer screen (shown above). They were shown microscopic images of breast tissue, some of which indicated the presence of cancer, and some of which did not. There were two “buttons” on the computer screen, one on each side of the image. One button represented the answer “this image shows cancer,” and the other button represented the answer “this image does not show cancer.” Each pigeon was free to choose either button, and if the pigeon was correct, it got a pellet of food.

At first, of course, the pigeons’ answers were random. Over time, however, they learned to look at patterns in the image, and within a matter of hours, they were identifying cancer at a rate that was superior to random guessing. Within a month, they were spotting cancer with about an 80% accuracy rate. The most interesting effect, however, was obtained when several birds were shown an image and their combined answers were used to determine whether or not cancer was present. When that was done, the accuracy of the diagnosis was 99%, which is about as good as a trained person!

One very important aspect of this study is that the birds did all their work alone, in the box. There wasn’t a person present. This is important, because many animals are extremely perceptive, and they can take visual cues from people, even when those cues are unconscious. Thus, whenever an animal can do something novel, there is always the possibility that it is responding to its caretaker, not performing the feat on its own. Since people were not present during the times the pigeons were shown the images in this study, it is clear that the birds were actually learning how to recognize patterns that indicate cancer.

Interestingly enough, the researchers repeated the experiment using mammogram images instead of microscopic images of tissue. When confronted with these images, the pigeons didn’t do nearly as well. The researchers tried to get them to spot suspicious masses in mammogram images, which is a difficult task, even for some trained people. While the pigeons could eventually memorize the correct answer for images that had been shown to them multiple times, they couldn’t look at a new image and correctly identify a problem, as they did with the microscopic images of tissue. Obviously, then, a pigeon’s pattern-recognition abilities are well suited to some types of images but not others.

Now please don’t think that the researchers carried out this study in the hopes of having pigeons do cancer diagnosis one day! They were trying to compare how pigeons learn to how people learn. While it’s not clear what this study can tell us about that, it is clear that pigeons are very good at learning to recognize certain patterns.

It gives a whole new meaning to the term “bird brain,” doesn’t it?

January 18, 2016

Universal Genetic Code? No!

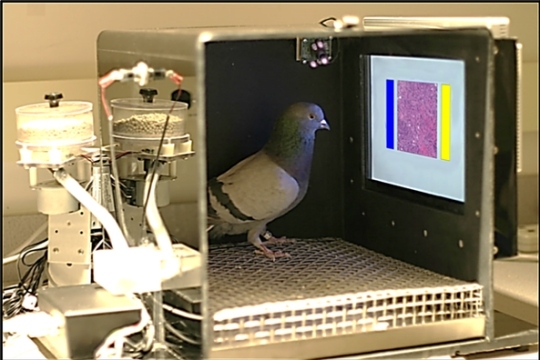

The basic process by which proteins are made in a cell. (click for credit)

I am still reading Shadow of Oz by Dr. Wayne Rossiter, and I definitely plan to post a review of it when I am finished. However, I wanted to write a separate blog post about one point that he makes in Chapter 6, which is entitled “Biological Evolution.” He says:

To date, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), which houses all published DNA sequences (as well as RNA and protein sequences), currently acknowledges nineteen different coding languages for DNA…

He then references this page from the NCBI website.

This was a shock to me. As an impressionable young student at the University of Rochester, I was taught quite definitively that there is only one code for DNA, and it is universal. This, of course, is often cited as evidence for evolution. Consider, for example, this statement from The Biology Encyclopedia:

For almost all organisms tested, including humans, flies, yeast, and bacteria, the same codons are used to code for the same amino acids. Therefore, the genetic code is said to be universal. The universality of the genetic code strongly implies a common evolutionary origin to all organisms, even those in which the small differences have evolved. These include a few bacteria and protozoa that have a few variations, usually involving stop codons.

Dr. Rossiter points out that this isn’t anywhere close to correct, and it presents serious problems for the idea that all life descended from a single, common ancestor.

To understand the importance of Dr. Rossiter’s point, you need to know how a cell makes proteins. The basic steps of the process are illustrated in the image at the top of this post. The “recipe” for each protein is stored in DNA, and it is coded by four different nucleotide bases (abbreviated A, T, G, and C). That “recipe” is copied to a different molecule, RNA, in a process called transcription. During that process, the nucleotide base “U” is used instead of “T,” so the copy has A, U, G, and C as its four nucleotide bases. The copy then goes to the place where the proteins are actually made, which is called the ribosome. The ribosome reads the recipe in units called codons. Each codon, which consists of three nucleotide bases, specifies a particular amino acid. When the amino acids are strung together in the order given by the codons, the proper protein is made.

The genetic code tells the cell which codon specifies which amino acid. Look, for example, at the illustration at the top of the page. The first codon in the RNA “recipe” is AUG. According to the supposedly universal genetic code, those three nucleotide bases in that order are supposed to code for one specific amino acid:methionine (abbreviated as “Met” in the illustration). The next codon (CCG) is supposed to code for the amino acid proline (abbreviated as Pro). Each possible three-letter sequence (each possible codon) codes for a specific amino acid, and the collection of all those possible codons and what they code for is often called the genetic code.

Now, once again, according to The Biology Encyclopedia (and many, many other sources), the genetic code is nearly universal. Aside from a few minor exceptions, all organisms use the same genetic code, and that points strongly to the idea that all organisms evolved from a common ancestor. However, according to the NCBI, that isn’t even close to correct. There are all sorts of exceptions to this “universal” genetic code, and I would think that some of them result in serious problems for the hypothesis of evolution.

Consider, for example, the vertebrate mitochondrial code and the invertebrate mitochondrial code. In case you didn’t know, many cells actually have two sources of DNA. The main source of DNA is in the cell’s nucleus, so it is called nuclear DNA. However, the kinds of cells that make up vertebrates (animals with backbones) and invertebrates (animals without backbones) also have DNA in their mitochondria, small structures that are responsible for making most of the energy the cell uses to survive. The DNA found in mitochondria is called mitochondrial DNA.

Now, according to the hypothesis of evolution, the kinds of cells that make up vertebrates and invertebrates (called eukaryotic cells) were not the first to evolve. Instead, the kinds of cells found in bacteria (called prokaryotic cells) supposedly evolved first. Then, at a later time, one prokaryotic cell supposedly engulfed another, but the engulfed cell managed to survive. Over generations, these two cells somehow managed to start working together, and the engulfed cell became the mitochondrion for the cell that engulfed it. This is the hypothesis of endosymbiosis, and despite its many, many problems, it is the standard tale of how prokaryotic cells became eukaryotic cells.

However, if the mitochondria in invertebrates use a different genetic code from the mitochondria in vertebrates, and both of those codes are different from the “universal” genetic code, what does that tell us? It means that the eukaryotic cells that eventually evolved into invertebrates must have formed when a cell that used the “universal” code engulfed a cell that used a different code. However, the eukaryotic cells that eventually evolved into vertebrates must have formed when a cell that used the “universal” code engulfed a cell that used yet another different code. As a result, invertebrates must have evolved from one line of eukaryotic cells, while vertebrates must have evolved from a completely separate line of eukaryotic cells. But this isn’t possible, since evolution depends on vertebrates evolving from invertebrates.

Now, of course, this serious problem can be solved by assuming that while invertebrates evolved into vertebrates, their mitochondria also evolved to use a different genetic code. However, I am not really sure how that would be possible. After all, the invertebrates spent millions of years evolving, and through all those years, their mitochondrial DNA was set up based on one code. How could the code change without destroying the function of the mitochondria? At minimum, this adds another task to the long, long list of unfinished tasks necessary to explain how evolution could possibly work. Along with explaining how nuclear DNA can evolve to produce the new structures needed to change invertebrates into vertebrates, evolutionists must also explain how, at the same time, mitochondria can evolve to use a different genetic code!

In the end, it seems to me that this wide variation in the genetic code deals a serious blow to the entire hypothesis of common ancestry, at least the way it is currently constructed. Perhaps that’s why I hadn’t heard about it until reading Dr. Rossiter’s excellent book.

January 14, 2016

Another Bad Sermon Illustration

An adult bald eagle in flight (click for credit)

I posted my previous blog article on my Facebook page, and someone asked about another sermon illustration that involves eagles. A typical version of that illustration is:

To convince the little eagles that the time has come to leave the nest, the parent eagles “stir up the nest.” That is, they rough it up with their talons, and make it uncomfortable, so that sticks and sharp ends and pointy spurs stick out of the nest, so that it is no longer soft and secure, ruining their “comfort zone.” The nest is made very inhospitable, as the eagles tear up the “bedding,” and break up the twigs until jagged ends of wood stick out all over like a pin cushion. Life for the young eaglets becomes miserable and unhappy. Why would Mom and Pop do such a thing?

But to make matters worse, then the mother eagle begins to “flutter her wings” at the youngsters, beating on them, harassing them, and driving them to the edge of the nest. Cowing before such an attack, the little eagles climb up on the edge of the nest. At this point, the mother eagle “spreads her wings” and, to escape her winged fury, the little eagle climbs onto her back, and hangs on for dear life. As if that were not enough, then the mother eagle launches out into space, and begins to fly, carrying the eagle on her back. All seems safe and serene, the little eagle never expected such a thrilling ride — but that was nothing to what was to come shortly. For suddenly, without any warning, the mother eagle DIVES, plummeting downward, depriving the little eagle of its “seat,” and the next thing it knows, it is in free fall, falling, and tumbling down, down, down, in the air, its wings struggling to catch hold of the air currents, but flopping crazily due to its inexperience. For it must learn to flow, and there is nothing like “experience” to teach an eagle to fly! Instinct alone is not enough!

Just at it thinks all is hopeless and lost, however, the mother eagle swoops down below and catches it once again on its back, and soars back into the atmosphere. Much relieved, the young eagle hangs on for dear life. But just when he thinks everything is “OK” once again, the mother pulls another sneaky trick, and dumps him into the air, alone, again! Once again, the little eagle struggles, this time his wings begin to work a little better, and instead of tumbling like a rock pulled by gravity to certain destruction below, he manages to slow his descent, and is able to stay aloft a little longer, as his wings begin to strengthen. Again, if necessary, the mother eagle rescues him from death, and soars back into the heavens. But just as he thinks everything is finally “hunky dory,” she does it again! And down he goes! Finally, he learns how to catch the air currents and ride the winds, and begins to soar “like an eagle” — and now experiences the thrill of total “freedom” and “liberty”! Now he is no longer confined to the parameters of the nest. Now he is free to soar in the sky, and to be a true “eagle.”

Like the previous one I wrote about, there is nothing true in this illustration.

The first thing you have to realize is that when a “baby eagle” is ready to fly (when it is 10-12 weeks old), it is about the same size as an adult. Eagles are amazing flying machines, but they can carry only about one-third of their weight in flight. Thus, even neglecting the horrible aerodynamics of the situation, it would simply be impossible for a mother eagle to carry its fledgling on its back.

The second thing you need to know is the parent eagles don’t have to make the nest “uncomfortable” for their fledglings to leave. The young eaglets have been watching their parents fly to the nest with food in their talons – food that the parents feed to the eaglets. This makes the eaglets associate flying with food. As a result, they eventually “want” to learn to fly themselves so they can get more food.

How do they learn to fly? The scientific term is branching. They imitate their parents, flapping their wings and hopping from branch to branch. When they are “brave” enough to actually leave the branches (usually with the help of a strong wind), they typically glide to a nearby tree. If they are hesitant to return to the nest, the parents try to lure them back with food. If they refuse to come back to the nest, the parents will feed them where they are, until they are able to reach the nest again. They stay close to the nest while they are practicing their flying technique, because they know they will get food if they stay close. Eventually, they master the art of flying and begin to hunt on their own.

There are several videos of eaglets learning to fly (see here, here, here, and here, for example), so there is really no excuse for someone using this illustration. It simply isn’t true.

January 11, 2016

A Bad Sermon Illustration

Eagles don’t do what one sermon illustration says. (click for credit)

A student who has used some of my science courses contacted me asking if something he heard in a sermon was actually true. He said that it sounded kind of hard to believe, based on what he knew about science. The student’s question made me happy for two reasons. First, it showed that he was diligent in trying to learn the truth. Second, it showed that he was able to take what he had learned from my science courses and use it to do some critical thinking.

Here is one version of the story he heard:

The eagle has the longest life-span among birds. It can live up to 70 years, but to reach this age, the eagle must make a hard decision. In its 40’s, its long and flexible talons can no longer grab prey which serves as food. Its long and sharp beak becomes bent. Its old-aged and heavy wings, due to their thick feathers, become stuck to its chest and make it difficult to fly. Then, the eagle is left with only two options: die or go through a painful process of change which lasts 150 days. The process requires that the eagle fly to a mountain-top and sit on its nest. There, the eagle knocks its’ [sic] beak upon a rock until it plucks it out. After plucking it out, the eagle will wait for a new beak to grow back and then it will pluck out its talons. When its new talons grow back, the eagle starts plucking its old-aged feathers. After five months, the eagle takes it famous flight of re-birth and lives for 30 more years!

The idea, of course, is that change is hard, but if you make the change, great things can happen. While this is an inspiring tale, almost nothing in it is true. Let’s just start from the beginning and work through the story, comparing what the story claims to what we know about eagles.

The eagle has the longest life-span among birds. It can live up to 70 years, but to reach this age, the eagle must make a hard decision.

Most eagles live 20-30 years in the wild. Some captive eagles have lived as long as 50 years. Albatrosses are among the longest-lived birds, with an average lifespan of about 50 years in the wild. The oldest known wild bird is a Laysan albatross that is about 64. She has a Facebook page, if you are interested.

In its 40’s, its long and flexible talons can no longer grab prey which serves as food. Its long and sharp beak becomes bent. Its old-aged and heavy wings, due to their thick feathers, become stuck to its chest and make it difficult to fly.

I guess its talons wouldn’t be able to grab prey, since the eagle is probably dead by the time it is in its 40’s! However, while it is alive, none of this happens. An eagle’s talons and beak are made of keratin, the same substance that makes your fingernails. They grow continually and are therefore constantly renewed. Thus, they don’t become bent or inoperable.

Also, feathers don’t become thick as a bird ages. All birds molt, which means they lose their feathers according to a programmed process that occurs regularly. An adult eagle will lose all its flight feathers slowly over the course of the spring and summer, replacing them with new feathers. This happens in a very precise way. When one feather on the left side of the body falls off, the corresponding feather on the right side of the body will also fall off. That allows the eagle to maintain balance during flight.

Then, the eagle is left with only two options: die or go through a painful process of change which lasts 150 days. The process requires that the eagle fly to a mountain-top and sit on its nest.

Eagles typically build their nests in trees, not on mountain tops. They tend to use the same nest each time they reproduce, but they never use the nest unless they are preparing it for their young, incubating the eggs, or caring for their young. A nest is not a bird’s home. It is a bird’s nursery.

There, the eagle knocks its’ [sic] beak upon a rock until it plucks it out. After plucking it out, the eagle will wait for a new beak to grow back and then it will pluck out its talons. When its new talons grow back, the eagle starts plucking its old-aged feathers. After five months, the eagle takes it famous flight of re-birth and lives for 30 more years!

This was the part that really bothered the student. Can you figure out the problem? Supposedly, this process takes five months. During that time, the eagle can’t eat. After all, for a while it has no beak. Then it has no talons. Then it can’t fly, because it has no feathers. The student specifically asked how the eagle could live that long without eating. He asked if some process like hibernation was going on.

I was really pleased that the student thought that through. There are animals that can live for extended amounts of time without eating. However, they generally achieve a low-energy state in order to do that. The eagle in this story isn’t in a low-energy state if it is growing a new beak, new talons, and new feathers! Obviously, then, this “renewal process” simply can’t happen the way it is described!

I am sure there are a lot of untrue sermon illustrations that are used time and time again, just as there are many untrue things written in science textbooks. It pays to be diligent. Check out those illustrations before you use them or repeat them!

January 7, 2016

C.S. Lewis Wasn’t an Anti-Evolutionist, but He Did Work for British Intelligence!

This collection contains some of C. S. Lewis’s most important works. (click for credit)

More than three years ago, I ran across two articles that mischaracterized C. S. Lewis’s views on creation. I wrote about both of them, but the one that distressed me the most claimed that Lewis was a “creationist and anti-evolutionist.” Since it so severely mischaracterized Lewis’s views, I asked the publisher, Creation Ministries International (CMI), to remove it from their website. At first, they did not. I wrote two other articles on the subject (here and here) and thought I was done.Later on, however, an email correspondence led me to write a detailed rebuttal of the article and send it to the journal in which it was originally published. The journal published my rebuttal and gave the author of the article space to respond (which is the proper thing to do). However, it was clear that he could not defend what he had done to Lewis’s words. As a result, CMI eventually withdrew the article. I am pleased that they did the right thing.

Why am I telling you this? Because I recently ran across another article about C.S. Lewis, and it makes an incredible claim: “C.S. Lewis Was a Secret Government Agent.” The article was written by a well-respected Christian academic, Dr. Harry (Hal) Poe, who is also an avid collector of items related to Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkein, and other literary figures who interacted with them. While the phrase “secret government agent” is a bit over-the-top, the essence of article seems quite reasonable, and it illustrates how someone as well-studied as C.S. Lewis can still harbor a surprising secret!

While the article is long (he is an academic, after all), the upshot is that Poe was searching eBay and noticed that someone was selling a 78 rpm record that supposedly contained a lecture by C.S. Lewis. Poe figured this had to be a hoax, because he had studied Lewis thoroughly, and there was simply no indication that a 78 rpm record had ever been made of any of Lewis’s lectures. Nevertheless, Poe was curious, so he bought it, and it turns out that the record seems to be legitimate! It is parts 1 and 3 of a series entitled “The Norse Spirit in English Literature.” Poe is now searching for parts 2 and 4.

Obviously, Poe wanted to learn more about this amazing find, so he did some digging. He found out that during World War II, Iceland had strategic significance. The British invaded it to take it from the Germans, but Britain needed to secure the good will of the people there. As a result, the Joint Broadcasting Committee (an arm of British intelligence) asked Lewis to record a lecture that would help the people of Iceland feel some kinship towards the people of Britain. The lecture for which Poe has parts 1 and 3 was the result.

Interestingly enough, this record clears up a bit of a mystery among C.S. Lewis scholars. In a 1941 letter to his friend Arthur Greeves, Lewis remarked that he had made a gramophone record of himself and then listened to it. He had never heard his own voice from a recording and was shocked at how he sounded. Scholars didn’t really understand what this statement referenced, since there was no known gramophone record with Lewis’s voice. However, the timing of the letter works perfectly if it is referencing this record. Dr. Poe plans to hold a public hearing of the record in July of this year.

Now as I said, the term “secret government agent” is a bit over-the-top. While Lewis did keep this recording secret from everyone in Britain, it was presumably broadcast in Iceland. Thus, he was not under cover or anything like that. However, he did do some work for an arm of British Intelligence, and it was kept secret from most people.

I find it astounding that a well-studied man like C.S. Lewis, who died less than 60 years ago, can still surprise those who are experts about his works and his life! It makes you wonder what other unknown works exist for other well-known writers!

January 4, 2016

Another Atheist Who Became a Christian

Dr. Wayne Rossiter holds a Ph.D in ecology and evolution from Rutgers University. (click for credit)

Over the holidays, I started reading a book entitled Shadow of Oz. I have yet to decide whether or not to post a full review of it, but I did want to point out what I have found to be the most interesting part of the book so far: the conversion story of its author, Dr. Wayne D. Rossiter.Dr. Rossiter earned his Ph.D. in ecology and evolution from Rutgers University in February of 2012 and is currently an assistant professor of biology at Waynesburg University. One thing I found so fascinating about his conversion story is that it is rather different from mine. Science caused me to doubt my atheism, and an investigation of the evidence led me to a belief in Christianity. For Dr. Rossiter, however, it was not science itself that caused him to doubt his atheism. Instead, what he saw as the consequences of atheistic science caused him to fall into the Savior’s arms. Here is how he begins his conversion story:

…I had developed into a staunch and cantankerous atheist by the time I got to Rutgers to pursue a Ph.D. This was aided by an equally atheistic advisor who was of Dawkins’s ilk. Advanced education at our best universities is surprisingly insular. Like bobbleheads, we tend to read and agree on the same things, and give little to no countenance to critics of our views. (pp. 3-4)

I couldn’t agree more with his take on the insular nature of advanced education in the U.S. I vividly remember several instances from my early years in academia where a “senior” member of a research group would make fun of a position with which he disagreed, and the rest of us would bob our heads in agreement without even trying to suggest that there might be good reason to at least examine that position seriously. At the time, I didn’t understand how anti-science such actions were, but now that I look back on them, I shake my head at the sorry state of our advanced education system.

What caused Dr. Rossiter to doubt his atheism? After achieving an important milestone in every academic’s life (publication in a major journal of his field), he and his wife celebrated. He stayed up after his wife went to bed, and he became plagued by the “big questions” about life:

On what rational grounds could I care about the state of the planet (or even my family) after I’m gone? And what did I even mean by “good” or “bad”? I couldn’t argue that any objective morality existed apart from our subjective experiences. Any moral laws that might objectively exist – whether or not anyone ascribes to them – would be beyond our grasp, and we would have no objective or rational reason to obey them if they did exist. Nothing mattered. This is Dennett’s “universal acid,” and Darwin’s ideas applied that acid to the human condition. If molecules led to cells, and cells to organs, and organs to bodies, then the “molecules-to-man” hypothesis was true. We really were just wet computers responding to external stimuli in mechanical and unconscious ways. No soul, no consciousness. Just machines. I was completely and utterly devastated. (pp. 4-5)

This led to some serious soul-searching, which included psychiatric counseling. His counselor was a Christian, and that intrigued him, so he read some intellectuals who found belief in God to be both rational and compelling. This caused him to doubt his atheistic view of science, and eventually, he became a Christian. The university at which he now teaches is a Christian university.

I have to say that I have never been impressed by the argument from morality, which is one of the issues he touches on in his quote above. I recognize that there are many who see it as the most convincing evidence for God’s existence, but it never swayed me as an atheist. Even now that I am a believer, I don’t see its power.

However, I do agree strongly with the last part of his quote. As I see it, if you believe that life is simply a collection of molecules whose interactions are guided by natural forces, there is no way you can believe in free will or consciousness. After all, if my brain is all there is to my mind, then there is no way for me to choose my beliefs or my actions. Indeed, my brain is simply a collection of cells, and those cells interact according to strict chemical and physical laws. There is no way to deviate from the outcomes required by those laws, so none of my actions or thoughts are my own. They are simply the consequences of the initial conditions of my brain and the interactions of its parts.

While this logical conclusion never convinced me to doubt my atheism (I was happy to be an automaton), I can see how it would cause others to do so. I thank God that it helped Dr. Rossiter to see the Light!

December 24, 2015

Another Christmas Drama

“The Adoration of the Shephers” by Gerard van Honthorst

In case you are new to this blog, you might not be aware that in addition to being a professional science writer, I am also an amateur playwright. The plays I write are for church, and most of them are short. For Christmas and some other special occasions, however, I write a longer play. The one you will find linked at the bottom of this post is the “sermon-length” (about 30 minutes) Christmas play that we performed at my church on December 20th during the worship service.

This one is more lighthearted than most of my plays, and it requires that the stage be dressed up in gaudy, secular Christmas decorations. They are there to make the point that Christmas is not about such things, but some churches may find them offensive. Also, there is one “special effect” that you can drop if you want, but it was really funny when we did it. When Marc said, “Hey, check this out, I can even make it snow,” he held up a homemade “snow machine” and made it snow.

The “snow machine” was actually just a leaf blower that I had filled with the fake, plastic snow you can buy pretty much anywhere that has Christmas decorations. In order to make the effect work, you need to remove the nozzle on the leaf blower so there is just an open tube remaining. The fake snow gets clogged up in the nozzle. Ideally, you would extend the tube so you can add more snow. I did it with a cardboard mailing tube taped on the end. Then I dumped enough fake snow into the extended tube so it was about 3/4 full. Don’t PACK the snow it. Just pour it in. Aim the leaf blower above the actors’ heads, and when you turn it on high, the fake snow will “explode” above them and gently fall on them. Of course, you can cut that effect if it’s too much trouble.

One other note: I wrote this play specifically for the people in our church. As a result, there are references that work specifically for those people. Marc really is our pastor, for example. He also leads worship, so when Sarah references that, it makes sense. The character named Jay is me, and I am in nearly every play we do. That makes Chris’s line about Jay being in a “few” plays funny. You can adjust those lines to make it work for the people in your church.

As is the case with all my dramas, feel free to use this in any way you think will edify the Body of Christ. If possible, I would like a credit, but that’s not nearly as important as using it to build up the church!

December 21, 2015

Exciting News in the Energy World

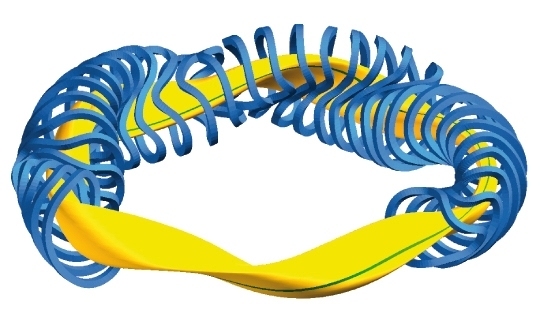

This illustration shows the coil system (blue) and plasma (yellow) design in the

Wendelstein 7-X stellarator fusion reactor. (click for credit)

Nuclear power has always presented the possibility of cheap, nearly unlimited electricity. So far, however, the reality has not lived up to the expectations, because we are using the wrong nuclear process. We have mastered using nuclear fission, which is the process by which large nuclei (like certain isotopes of uranium and plutonium) are split into smaller nuclei. This produces a large amount of energy, but it also produces a large amount of radioactive waste. In addition, the reaction can get out of hand, as we have seen in Chernobyl and Fukushima.

However, some countries have utilized nuclear power well. France, for example, currently gets 75% of its electricity from nuclear power. But even France is transitioning away from it, as it is planning to produce only 50% of its electricity that way by the year 2025. With the high-profile disaster at Fukushima and the problem of radioactive waste, it is understandable why even France is trying to move away from nuclear power.

If we could only master the opposite process, nuclear fusion, we wouldn’t have such problems. In fusion reactions, small nuclei (like certain isotopes of hydrogen) are combined to make a larger nucleus. If the nuclei are small enough, this also produces energy. The nice thing about nuclear fusion is that the byproducts are not radioactive, and the reaction is easy to stop. Indeed, it is hard to keep the reaction going! In addition, hydrogen is more abundant than uranium and plutonium.

Why don’t we use nuclear fusion to produce electricity? Because it’s harder than it sounds. Nuclei are positively charged. When you push two positively-charged things together, they repel one another. The closer they get, the more strongly they repel. In order to get two nuclei to combine, they have to get really close together. It takes a lot of energy to make that happen, and so far, the energy we spend trying to force it to happen is more than the energy we get from the reaction.

We know it’s possible to get more energy from the reaction than it takes to get the reaction started, because the sun produces its energy via nuclear fusion. However, the sun has a massive gravitational field that can get the reaction going. We can’t use gravity to start the reaction, so we have to use some other form of energy. One possibility is through the use of lasers. However, that technique isn’t working nearly as well as had been hoped. The other possibility is through the use of magnetic fields.

In this process, called magnetic confinement, a hot sample of hydrogen plasma is injected into a reactor that uses magnetic fields to squeeze the hydrogen nuclei together. Billions of dollars have been spent in trying to get this process to work. While progress has been made, no such reactor has yet been able to get as much energy out of the reaction as it has put into the reaction. In other words, no magnetic confinement reactor has yet “broken even” in terms of energy.

One difficulty that magnetic confinement faces is the tendency for plasma to “leak out” of the magnetic field, due to physical issues associated with the shape of the nuclear reactor. This has been known for quite some time, so in the 1950s, Dr. Lyman Spitzer designed an oddly-shaped magnetic confinement reactor that reduced such tendencies. This kind of reactor is called a stellarator, and its odd design is illustrated above. The stellarator built by Spitzer in 1951 at Princeton worked well. It didn’t break even by any means, but it was able to get nuclear fusion to occur.

The stellarator design was abandoned, however, because a simpler design (called a tokamak) showed some very promising initial results, and the simplicity of the design (at least compared to a stellarator) was quite attractive. As a result, tokamaks have been the focus of magnetic confinement fusion research for the past 40+ years. I remember sitting in the national American Chemical Society meeting back in 1990 and listening to a presentation that assured us the tokamak design would reach break even by 2010 at the latest. That never happened.

Because the tokamak design has not lived up to its initial expectations, some researchers have gone back to the stellarator design. While it is a lot more complex, it does have the potential to produce fusion that lasts for a longer time, because the magnetic fields contain the plasma better. This should produce more energy for roughly the same initial amount of energy required to get the reaction going, so a stellarator might be able to do what a tokamak has so far not been able to do.

Well, the first test of a modern, large-scale stellarator reactor recently happened, and it was a success! Now don’t get too excited. It was a first test. It didn’t even use hydrogen as the fuel. Instead, it used helium. Why? Because it’s easier to make a plasma from helium than it is from hydrogen. In addition, it didn’t try to make energy. The researchers just wanted to see if the design could hold a plasma as expected, and it did!

The researchers plan on working out how to make the best plasma they can for the reactor, and then they will switch to using the proper fuel, hydrogen. At that point, they will start detailed measurements of how much energy is put into the reaction and how much is produced by the reaction. They expect such experiments to start within a year or so. It will be interesting to see how they go.

The possibility of cheap, clean, nearly unlimited power is exciting, but I also find this turn of events rather interesting. After I listened to that American Chemical Society presentation in 1990, a group of us went out to dinner. I asked a my colleagues (most of whom were much more experienced in the field) why the stellarator design was not being pursued, as it seemed superior to me. I was told that the stellarator was “old technology” and that the tokamak design was the future. After investing 40+ years and billions of dollars into “new technology,” some nuclear scientists are seeing the advantages of the “old technology.”

Newer isn’t always better!

December 17, 2015

It’s Not That Simple!

This Black Angus cow is not happy about a study done by Carnegie Mellon University!

(click for credit)

It always bothers me when people make overly simplistic statements about the issues we are currently facing. It bothers me even more when scientists do it. Nevertheless, I find examples of scientists making overly simplistic statements time and time again, especially when it comes to “global warming,” aka “climate change.” I have discussed at length the overly simplistic way in which some scientists approach climate (see here, here, here, here, and here, for example). Not surprisingly, those same scientists often approach the “solutions” to global warming just as simplistically.

Consider, for example, this story from The Guardian. The headline says it all:

Eating less meat essential to curb climate change, says report

The article’s main discussion point is a report issued by a thinktank known as Chatham House, but it discusses several sources in which scientists and policymakers insist that we must reduce our meat intake in order to curb global warming. Why? It seems simple enough. Keeping livestock requires energy, and the livestock themselves produce greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane. It only makes sense that eating food coming from plants (which consume carbon dioxide and produce little methane) would reduce greenhouse gas emissions, right?

Well, a study done by Carnegie Mellon University concludes precisely the opposite!

In this study, the authors consider the energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and blue water footprint* associated with various types of food production. They then correlate those to three possible shifts in U.S. diet. First, they consider what would happen if people in the U.S. would stop overeating and just eat enough to maintain a non-obese body weight. Second, they consider what would happen if we all ate the same amount of calories but shifted to the more healthy diet recommended by the USDA. This would require eating less meat and dairy while eating more fruits and vegetables. Finally, they consider what would happen if we did both.

The results of the first scenario aren’t very surprising. If we ate fewer calories, all three things they considered (energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and blue water footprint) would decrease. This, presumably, would be good for both people and the environment. The other two results, however, are surprising, at least if you look at nature in a simplistic way. If we all continued to eat the same number of calories but switched to a healthier diet (which means less meat and dairy, more fruits and vegetables), energy use would increase by 43%, blue water footprint would increase by 16%, and greenhouse gas emissions would increase by 11%.1

So just shifting to a diet that is richer in fruits and veggies doesn’t help us reduce our supposed impact on climate. In fact, it makes our impact worse. But what if we did both? Would the reduction of calories offset the problems produced by switching to a diet richer in fruits and veggies? The answer is no. If we did both, we would still increase our energy use by 38%, blue water footprint by 10%, and greenhouse gas emissions by 6%. According to this study, then, if we truly want to reduce our impact on climate change, we need to increase our consumption of meat and dairy!

How did the policymakers and scientists discussed in The Guardian article I linked to previously get it so wrong? Because they looked at nature too simplistically. Yes, animal products do have a lot of energy and greenhouse gas emissions related to them, but then again, they require a lot less dedicated farmland. This reduces the energy needed to maintain them. It also makes more land available for year-round plant habitation, which should consume greenhouse gases.

In addition, meat and dairy products contain a lot of fat, and from a Calorie standpoint, fat is a very efficient delivery system. Each gram of proteins and carbohydrates (the main sources of energy in fruits and vegetables) contains only about 4 Calories per gram. However, fat contains about 9 Calories per gram. So when it comes to Calories, you eat less than half as much fat as you do proteins and carbohydrates. Thus, you eat less food on a diet that is rich in meat and dairy. I am sure there are many other factors that are important, but those are the two I can think of right off the top of my head.

Now please understand that I am not saying this study is definitive. It has to make assumptions, and it has to ignore certain processes in order to make the study manageable. If you make different assumptions and ignore different processes, you can come to the opposite conclusion, as one study has done.2 My point is that most policymakers and scientists arrived at their conclusions regarding global warming and food consumption by looking at things in an overly simplistic way. When you actually study the problem in a less simplistic way, you can come to a different conclusion.

Of course, if you think the earth was thrown together by random interactions governed by the laws of physics, you are prone to look at it as a simple system. As someone who thinks the earth has been marvelously designed, however, I expect it (and the processes that govern its life) to be much more complex. That, of course, is what serious science tells us.

REFERENCES

December 14, 2015

This is So Cool!

The box-patterned gecko has an amazing way to stay dry!

(click to see video from which this image was taken)

Studying God’s creation fills me with constant wonder! It is amazing to see how incredibly well-engineered the world and its inhabitants are. Even well-known, well-studied things can surprise us with a new piece of technology that we never imagined. So it is with the gecko. Scientists have marveled at the gecko for years because of the way it can climb almost any surface, and they have studied it so thoroughly that engineers can crudely mimic its climbing ability. The gecko is so well designed that we haven’t completely figured out the details of how it climbs, but we at least have the basics, and they have been known for a while now.

A recent study shows us that at least one species of this amazing group of lizards, the box-patterned gecko, has another marvelous design feature: the ability to repel water in a most ingenious way. The gecko’s skin is covered in microscopic spines called spinules. These spinules force the water to form into droplets, and as the droplets grow in size, they are eventually propelled away from the body! If you click on the picture at the top of this post (and I strongly suggest that you do), you will be able to see a wonderful video of how this happens.

Why would the gecko have such a marvelously-designed system for repelling water? The authors of the study1 suggest that it reduces the ability of bacteria and fungi to grow on the skin, and it may help clean the skin of certain contaminants. Whatever the reason, I love the fact that we are still learning things about this well-studied animal!

REFERENCE

Jay L. Wile's Blog

- Jay L. Wile's profile

- 31 followers