David Scott Bernstein's Blog, page 30

October 14, 2015

Don’t Show me your Private Parts

What’s a private method, why use them? Their purpose is to hide implementation details, the way we accomplish a task. We generally don’t want to share these details so we limit its scope and who can call it.

Use private methods to share common implementations so a service can have different APIs for different client’s needs. But also use private methods whenever there’s any bit of functionality that you can name but don’t need to expose to the outside.

When I mark something as private I’m saying the world doesn’t need to know or care. I’m telling other developers they don’t have to worry about what’s inside. Of course, private methods don’t bloat an object’s interface and can provide an extra measure of security as private methods can’t be called from outside the object that contains it. Keep as much as you can private and only expose what is required to use your service.

Try not to expose implementation details so that you’re free to change them later without impacting the system. Do this by following the advice from the Gang of Four (GoF): design to interfaces, prefer aggregation, and encapsulate variation.

Offer your services through an interface based on the callers’ needs then adapt it. Present what you want, not how to get it. Code to abstractions rather than concrete classes. As you do these things, classes get defined responsibilities and the domain model remains crisp.

But don’t tell me how you’ll do something, don’t even imply it. That forces you to commit to a particular implementation. Keep those details private instead.

How do you test private methods? The short answer is you don’t, at least not directly. If you can exercise the behavior of a private method by calling its public interface then your private method will have code coverage and you can consider it tested. If you feel that the private method does so much that it really needs its own test then it probably shouldn’t be private. In those cases, you can put the behavior in a public method in its own class that’s held privately. This gives you testability and potential reusability of the behavior without bloating the interface of the client.

October 7, 2015

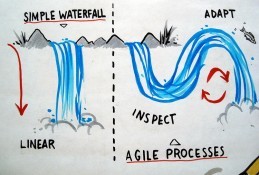

The REAL Difference between Agile and Waterfall Development

What’s the real difference between Agile and Waterfall? Is it short iterations, standup meetings, having a ScrumMaster, or what?

Clearly, there are many differences between Agile development and Waterfall development. Agile involves less planning and more feedback but those are not the major differences from Waterfall. Some people will tell you that it’s a “mindset” shift but that isn’t very specific either.

I’d like to propose one key difference between Agile and Waterfall that seems to make the biggest difference: how frequently you integrate. This may not seem like the most important distinguishing factor but in reality it’s one of the main drivers of agility.

How frequently we integrate predetermines our development process. If we integrate code after it’s written, even just a few weeks after, then we’re really doing mini-Waterfalls and not Agile. It’s only when we continuously integrate that developers get the instant feedback that shifts the dynamic of development.

Remember Pavlov’s dogs? Stimulus and response has to happen close together, otherwise we won’t see the connection. The same is true for all of us. We have to see the consequences of our actions immediately, not in days, weeks, or even months later. If we don’t, we won’t make the connection between our actions and the end result. This is why Waterfall development is still popular even though we all know it doesn’t work.

At the end of a Waterfall project when code is integrated we usually find the worst bugs. I remember dreading integration on the many Waterfall projects I worked on back in the day. I don’t have that dread integrating code anymore because I integrate my code as I build it.

Integrating code as it’s built removes the dreaded integration phase in Waterfall development and turns our biggest impediment into our richest form of feedback. Integrating a year’s worth of development can be insanely hard but integrating what I did in the last hour (or few minutes) is very simple and I can immediately fix any problems while it’s still fresh in my mind.

We’re all familiar with the idea that it costs orders of magnitudes more to find and fix bugs after release than it costs if a bug is found immediately after it’s written. We want to find bugs when the code is still fresh in our minds. When we do we get instant feedback on what works and what doesn’t work and that immediate feedback is what we need to change our behavior. In a very real sense, we know what not to do and we stop doing it, without even thinking about it. That’s the real value of Agile development.

September 30, 2015

What Mr. Robot Says About Bugs

Sometimes we act as if bugs just appear in our code on their own, but we all know that’s not true. The bugs in my code were written by me. I didn’t mean to write them. I didn’t want to write them. But I did anyway.

I remember when I first heard Al Shalloway refer to a bug as code he had written and it hit me, I’m the author of the bugs in my code. There was no one else to blame but me.

Many teams I meet hoard bugs. Instead of heeding the message that bugs are telling us or fixing them as soon as they are found, they collect them, track them, and tell themselves that someday they’ll get rid of them.

Good luck.

Hoarding bugs is demoralizing, and their numbers just grow and grow until there are so many bugs it becomes uneconomical to address them so they either learn to live with most of them or the bugs pull their project under. Neither of these are good outcomes.

Bugs are often the tip of the iceberg, they’re the harbinger of something much worse to come, a warning sign that things are headed awry. We must heed these warnings and not ignore them.

Bugs can hide and finding them can often be the hardest part of getting rid of them. My friend Llewellyn Falco says that finding a bug in a large program is like being told there’s a misspelled word in a dictionary. Fixing a misspelled word is easy, finding the misspelled word can be time consuming and tedious.

In the TV show Mr. Robot, eps1.2_d3bug.mkv, Elliot says, “Debugging is actually all about finding the bug. About understanding why the bug was there to begin with. About knowing that it’s existence was no accident.”

I love this quote and I say something very similar in my new book, Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software. On page 26, I write:

I’ve been dealing with bugs for many years as a developer, but I’ve only recently started to see them for what they really are: flaws in my software development process.

And like insects, software bugs need the right conditions to breed.

Bugs don’t just happen, we let them happen. And we have the power to stop them. If we don’t then they can get out of hand.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Instead of hoarding bugs or hating bugs we can recognize them for the messengers they are and heed their message to get back on track. Every bug is a missing test, a critical distinction I failed to realize. If I can see this then I can not only fix that one bug but vanquish a whole class of bugs. If I can see a bug for what it truly is then it becomes my teacher and I become its grateful student.

September 23, 2015

What Managers Must Understand

Back in the 1990s, I was teaching a class at IBM’s wildly successful Cottle Labs in San Jose, CA. It was mid-week, halfway through the class, which had been going really well up to that point, when the students coming back from lunch looked like a train had hit them. Moments before they had just received an email from their manager: they had all been fired.

They were told to finish the class for the rest of the week and then on Friday afternoon to collect their belongings, and find a new position within the company because their project was canceled. Canceled projects were and still are pretty common. According to the Standish Group, 31% of projects were canceled in 1994 and by 2012 that figure shrank to 18%.

All failure is tragic but this was particularly so because it was avoidable. The developers had warned management of the impending collapse but management ignored their warnings. If only their managers understood the situation the way the developers did. But they didn’t.

Over the years I’ve seen something similar play out over and over. The developers have one perspective and management has another. Both groups are caring, responsible people, who want the best for their company, so why don’t they see eye to eye? The way we build software is so alien to people who don’t do it that managers often have a hard time trying to fathom the issues developers face. After that incident, I promised myself I’d try to help the people who manage software developers understand what they’re managing.

But I failed.

For nearly twenty years after that I focused on helping developers deepen their understanding of the virtual domain and I left the non-developers in the dust. I did this partly because I enjoy working with other developers and partly because I needed to deeply understand the nature of software myself.

All that changed for me about two years ago when I started writing my book, Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software. I wanted to explain the reasoning behind the technical practices of software development so simply that anyone, including non-developers, could understand. At the same time, I realized that many developers, even highly experienced ones, didn’t have a firm grasp of the reasoning behind many of the technical practices, which caused them to not get as much value from them as they should.

As Einstein once said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” Software is really not all that difficult, it’s just different. All of the technical practices boil down to common sense. When we can see that “simplicity at the heart of complexity” it gives us insights. These are the kind of insights I share in my book, Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software.

I started out writing a book for managers to explain why the technical practices of software development are important and found that the content was valuable to many developers as well. I wrote this book to help developers and non-developers get on the same page with the most valuable yet least well-understood technical practices in software development. As far as I know, this is the first book of its kind.

It turns out that only geeks like to read technical manuals. When most executives think about curling up with a good book, Clean Code or Refactoring are probably not the titles that come to mind. People like stories that engage them so I wrote my book drawing heavily on narrative non-fiction. I tell stories, use metaphors, and draw on a wide range of information from a diverse range of areas that I then relate back to software. I wrote it to be interesting and engaging. You can find out more at http://BeyondLegacyCode.com.

September 17, 2015

Ideal Days Aren’t Ideal

I consider myself a supporter of the #NoEstimates hashtag. It’s not that I think estimates are evil, it’s just they’re often unneeded or misapplied. If the effort to estimate a task is equal to the effort required to complete the task then is an estimate worth it?

Estimates can be useful for measuring capacity or how much work a team can accomplish in a short period of time. In the past, I’ve estimated work in terms of ideal days. An ideal day is how much work can be accomplished in a day with no interruptions. Because we’re human we can’t utilize every moment to be productive so we generally say an ideal day is equal to about two real days. This may seem reasonable but there’s a major flaw with it that I didn’t realize until just recently.

When estimating in days (ideal or otherwise) we put an upper limit on how much work we can get done. When I say a task will take me seven days to complete, I’ve locked myself in to how long it will take.

Instead of sizing the time to complete a task, try sizing the *effort*. Find the easiest story in your backlog, what everyone agrees is trivial, and give it a value of 3. Then rank other stories relative to that one in terms of effort to complete. Use the Fibonacci series (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13+) to rate relative effort. You’ll find the amount of effort to accomplish a 3 will change over time and that’s fine. As a team’s abilities improve what was an 8 may become a 3. It doesn’t matter. What does matter is how much work the team can accomplish in this iteration.

By estimating effort instead of time to accomplish a task we increase our short term accuracy. At the same time, we decrease our ability to compare estimates through time or across teams. We should never do those things anyway. Estimates can be used to measure capacity and should never be used to measure productivity. It’s easy to misuse estimates or treat them like commitments but they shouldn’t be used in this way.

I was at a presentation recently that was filled with XP developers and the presenter showed two burn down charts from two different teams. Despite the fact that we all should know better we couldn’t help but compare the two teams. Then someone noticed that the scale on the charts were different. “Can we compare trends?” someone asked.

Let’s face it, we’re inference machines, we can’t help but find patterns, draw conclusions, etc. It’s what makes us human and it’s not so easy to turn off when we know we shouldn’t try. Some of the top teams I know don’t track velocity. How about your team? Do you track velocity? Do you use it in any other way than to measure how much work can be done in the next sprint? Is it worth it?

September 10, 2015

Requirements Aren’t Required

In traditional software development, up to half of all development time is spent writing, maintaining, and interpreting requirements. Even more than bugs, requirements are the single largest time sink in developing software. But what’s the alternative? How will developers build what the customer wants if they aren’t told what the customer wants?

The full answer is too long for a blog post. I cover it in my book, Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software (http://BeyondLegacyCode.com). It involves making development a discovery process where developers and the Product Owner engage in discovering what the customer really wants and by looking at who will use the software and what their goals are.

This might sound like a shoot-from-the-hip process but it isn’t. It’s a highly disciplined approach. There are many techniques one has to practice to do this successfully. But unlike requirements, it isn’t a rigid process so it leaves room to take advantage of new insights and learning in order to build something better than what the customer originally asked for.

Few developers can visualize a complex system before it’s built. And we do this for a living! What hope is there for non-technical people to fully visualize and describe exactly what a system should do before it’s written? This is not what humans are good at.

What we’re good at is recognizing if what we see is what we want, so let’s do that. Let’s build a little and ask for feedback. Let’s work through a couple of examples together. Let’s personify our different users by giving them a name and a back story so we better understand their needs. Let’s discuss why they want a feature in the first place and use our skills to exceed their expectations.

When we do this two very important things begin to happen. First, people get engaged. Customers see developers responding to their feedback so they become more invested in the solution and they’re much more likely to accept, use, and value what’s being built. After all, it was their idea in the first place. (I learned this trick from my wife, who’s a video producer. For more on that see https://tobeagile.com/2013/01/09/seven-strategies-for-customer-collaboration/) Developers are also more engaged as a result. Secondly, knowing why a customer wants a feature gives developers the freedom to come up with a better solution that addresses the customer’s real concerns. Often, we end up delivering something better than expected.

Most of development is about learning and only a part of our effort is about embodying that learning in code. The longer we work on a project the more we know so we’d like to use development to learn how to better satisfy our customers. But too often requirements become the centerpiece for development that must be adhered to even when we discover something better.

Throw away requirements documents and replace them with a knowledgeable, responsive, passionate Product Owner who can describe what the customer wants and be there to answer the myriad of questions that come up in the course of development. This will help keep the team engaged and focus development on the things that matter most to your users.

September 3, 2015

Build Once Then Enhance

In his book *Mythical Man-Month,* Frederick Brooks says to build a system “three times” by designing, implementing, and testing software. But this approach tends to amplify our mistakes rather than allow us to learn from them. It’s based on the false assumption that we can articulate a system’s behavior in the design documents with sufficient detail so as to make implementation merely a matter of following the design.

This has long been the dream of senior management because, as in building construction, the architect is a highly skilled (and highly paid) professional but the rest of the crew merely has to follow the directions outlined in his design documents. Construction workers don’t require a lot of specialized training and therefore don’t demand high salaries.

But software development is different. Requirements and design documents are not blueprints for software construction. In software, design and construction are inextricably linked. It can’t be separated out and a great deal of design decisions have to be made in the moment.

A much better approach is for developers to start by working through concrete examples. Examples give form to abstract concepts so they’re easy to think about, discuss, and find inconsistencies in. Working through an example isn’t a commitment to a particular implementation and it can give us lots of insights on how to best approach a design.

Working through a few examples gives developers enough perspective so they can form the right generalizations. This helps them find the right level of abstraction to apply when coding. And then, rather than launching into a testing phase to assure quality, we instead focus on cleaning up the code to *build supportability into the code we write* so we can continually improve our design and end up with a much better result.

August 27, 2015

Playing All or Nothing

Let’s imagine that I run a roulette table with a one-dollar minimum bet. According to http://wizardofodds.com/games/roulette/ the odds are one in thirty-seven on a single-zero wheel that your number will come up. Vegas would pay back accordingly, so if you bet $1.00 on 18 and the little ball lands on 18, the dealer hands you a cool $35. But let’s say that on your $1.00 bet on 18, I’ll pay you $1,000,000. That would be a popular table in any casino, with a one in thirty-seven chance of winning a one to a million payout with only a $1.00 investment.

But if in order to win the million dollars you had to get the exact number a hundred times in a row, you might be a little more reluctant to play, especially if you had to bet all $100 up front. If I said you had to win ten thousand times in a row, and put all $10,000 on the table before the first spin, I doubt anyone would try.

Even the most casual Vegas gambler is doing some version of a cost-benefit analysis on any particular game. If I drop a nickel in a slot machine there’s a very tiny chance I could win, say, $500—or 10,000 times my bet—but the worst that’s going to happen is I’m out five cents. No big deal. But if I have to be willing to risk $100,000 on Blackjack in a weekend if I want to go home with a million bucks, or only ten times my bet, that’s a much bigger risk.

Next time you’re in Vegas count up the number of Blackjack tables, then see how long it takes you to double, triple, quadruple (and so on) that number as you start counting the number of slot machines—and the number of people playing them.

Developing software is that way too, we take calculated risks. We either want the odds to be in our favor, or the potential loss to be negligible. In Waterfall software development where we integrate and test at the end of a long development cycle, we get neither. When we put off integration, it’s as if we’re playing roulette where we have to win a hundred times in a row in order to succeed. If anything doesn’t work, if one spin of the roulette wheel goes against us, nothing works.

That’s a very dangerous, risky casino we’re playing in.

One mistake in the way even a single line of code was written and a program won’t compile, or if it can compile it crashes when you run it. And even once the bug reveals itself it’s usually too late to do anything about it. By batching up features into long release cycles we’re building up more and more risk, which is only mitigated when the software we’re writing is integrated and tested at the very end of development.

Would you write code blindfolded with one hand tied behind your back? Probably not consciously, but we routinely do something similar in most development shops. We write code and compile it but often don’t see how it interacts with the rest of the system until right before we ship. This is when we find out about the nastiest bugs, when it’s too late to do much about it, but try to patch it as best we can.

That’s the real danger of building in a Waterfall environment. We lie to ourselves along the way, sure everything will be fine and the QA team will be able to deal with any little issues quickly and efficiently when it gets to them. But there’s no validation or verification till the very end of the process when it’s usually too late to do much about. It’s amazingly dangerous.

If anything doesn’t work, if one spin of the roulette wheel goes against us, nothing works.

Even a decade and a half into the Agile “revolution” and far too many of us are still playing in the Waterfall casino where we build software in large batches and put off integration until right before release. That’s a very dangerous, risky casino we’re playing in.

August 13, 2015

Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software is Here!

I can’t begin to describe how excited I am to announce the release of my first book!

Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software, published by Pragmatic Bookshelf, is based on my decades’ worth of hands-on experience as a software developer, consultant, and educator. I have seen all nine practices described in the book work, and work for some of the biggest players in the software industry.

Here’s an inside look at some of what you’ll find in Beyond Legacy Code, starting with why we need “practices” in the first place:

Chapter 4 – The Nine Practices

Building software is complex—perhaps the most complex activity that humans can engage in. Writing software is a discipline that requires a range of skills and practices to accomplish successfully.

It’s easy to get it wrong because the virtual world is so different from the physical world. In the physical world, we can easily understand what it takes to build something, but in the virtual world this can be much more difficult to see and understand. The software development profession is just starting to figure things out, much like where the medical profession was a few hundred years ago.

It was less than two hundred years ago that the medical community laughed at Ignaz Semmelweis for proposing that microscopic creatures could cause disease. How could something as trivial as washing your hands before surgery make the difference between life and death to your patient?

The medical community held this view in part because germ theory did not exist yet and partly because they were at that time actively trying to dispel the myth that invisible spirits caused disease (often truth and myth share a lot in common). Therefore, the practice of washing your hands before performing surgery wasn’t considered essential.

Battlefield surgeons in the Civil War knew about germ theory, but they argued they had no time to sterilize their instruments. If a soldier needed an amputation they didn’t have time to wash the saw. But when the medical community looked at the success rates of battlefield surgery they discovered that in many cases more men died of infection and disease in the Civil War than died on the battlefield, so medicine had to rethink its position.

When we understand germ theory, we understand why we have to wash all the instruments. This is the difference between following a practice (the act of sterilizing a specific instrument) and following a principle (the reason for sterilizing all instruments).

And the thing about the following software development practices, just like sterilization, is that we have to get it all right for any of it to work. If we happen to miss one of those things… one germ can kill your patient, and one bug can kill your application. And in this we require discipline.

I don’t believe there is one right way to develop software just as there’s no one right way to heal a patient, create art, or build a bridge. I don’t believe in the “one true way” of anything, but especially not for programming.

Still, having worked with thousands of developers, I’ve seen firsthand how we constantly reinvent the wheel. Software development has attracted a range of people from all backgrounds, and that has brought many fresh perspectives to creating software. At the same time, the huge diversity among developers can be a real problem. Enterprise software development involves enormous attention to detail and a lot of coordination among those involved. We must have some shared understanding, a common set of practices, along with a shared vocabulary. We must arrive at a common set of goals and be clear that we value quality and maintainability.

Some developers are more effective than others, and I’ve spent most of my life trying to discover what makes these extraordinary developers so good. If we understand what they understand, learn some principles and practices, then we can achieve similar extraordinary results.

But where to begin?

Software design is a deep and complex subject and to do it justice requires a great deal of background theory that would need several books to explain. Furthermore, some key concepts are not yet well understood among all developers and many of us are still struggling to understand the context for software development.

In many ways, legacy code has come about because we’ve carried the notion that the quality of our code doesn’t matter—all that matters is that software does what it’s supposed to do.

But this is a false notion. If software is to be used it will need to be changed, so it must be written to be changeable. This is not how most software has been written. Most code is intertwined with itself so it’s not independently deployable or extendable, and that makes it expensive to maintain. It works for the purpose it was intended for, but because of the way it was written it’s hard to change, so people hack away at it, making it even harder and more costly to work with in the future.

We want to drop the cost of ownership of software. According to Barry Boehm of the University of Southern California, it often costs 100 times more to find and fix a bug after delivery than it would cost during requirements and design. We have to find ways to drop the cost of supportability by making code easier to work with. If we want to drop the cost of ownership for software, then we must pay attention to how we build it.

Want more? Download the full excerpt here.

Buy Now

In the first of the nine practices we look at some of the problems facing far too many software development teams as they struggle just to get started:

Chapter 5 – Practice 1: Say What, Why, and for Whom Before How

Up to 50% of development time in a traditional software project is taken up by gathering requirements. It’s a losing battle from the start. When teams are focused on gathering requirements, they’re taking their least seasoned people—business analysts who don’t have a technical orientation in terms of coding—and sending them in to talk to customers. Invariably they end up parroting what the customer says.

We all have a tendency to tell people what we think they want to hear, and some customer-facing professionals still fall into this trap. It’s uncomfortable to try to find a way to tell your customer, “No, you don’t want that, you want this,” or “Let’s not worry about how it works and instead trust our developers to get us there.”

It’s easier to list the features requested by the customer and tell them exactly what we think they want to hear: “Got it. We can do that.” But can we?

More importantly, should we?

It’s natural in spoken language to talk in terms of implementation. That’s how people tend to speak, and it’s hard to identify when we’re doing that. I go from my specific understanding to a generalization. You hear that generalization and go back to your specific understanding. And in the end we have two different experiential understandings of what we think is common ground, but they’re probably completely different.

Requirements have no form of validation and that’s translated from the customer telling the analyst, the analyst writing it down, the developer reading it and translating it into code… It’s the telephone game. There are all these different ways of reinterpreting stuff so when you finally give the released version to the customer they’re apt to say, “That’s not what I said. That’s not what I wanted.”

Want more? Download the full excerpt here.

Buy Now

And the last of the nine practices addresses the legacy code crisis head on with advice for working with legacy code, but most of all, how and why the practice of refactoring code before it’s released can stop legacy code from propagating in the first place:

Chapter 13 – Practice 9: Refactor Legacy Code

Refactoring is restructuring or repackaging the internal structure of code without changing its external behavior.

Imagine you’re where I was a few years ago, saying to your manager that you want the whole team to spend two weeks, a full iteration, refactoring code. My manager said to me, “Good. What new features are you going to give me?”

And I had to say, “Wait a minute. I’m talking about refactoring. Refactoring is changing the internal structure but not changing the behavior. I’m giving you no new features.”

He looked at me and asked, “Why do you want to do this?”

What should I say?

Software developers are faced with this situation too often. Sometimes we don’t quite know what to say, because we don’t speak management’s language. We speak developers’ language.

I shouldn’t tell my manager I want to refactor code because it’s cool, because it feels good, because I want to learn Clojure or some other piece of technology… Those are all unacceptable answers to management. I have to specify the reasons for refactoring in a way that makes sense to the business—and it does.

Developers know this, but need to use the right vocabulary to express it—the vocabulary of business, which comes down to value and risk.

How can we create more value while at the same time reduce risk?

Software by its very nature is high risk and likely to change. Refactoring drops the cost of four things:

comprehending the code later,

adding unit tests,

accommodating new features,

and doing further refactoring.

Clearly, you want to refactor code when you need to work with it some more to add features or fix bugs—and it makes sense in that case. If you never need to touch code again, maybe you don’t need to refactor.

Refactoring can be a very good way to learn a new system. Embed learning into code by wrapping or renaming a method that isn’t intention revealing with a more intention-revealing name. You can call out missing entities when you refactor and basically atone for any poor code written in the past.

We all want to see progress and meet deadlines, and as a result we sometimes make compromises. Refactoring code cleans up some of the mess we may have made in an effort to get something out the door.

Want more? Download the full excerpt here.

Buy Now

Come back for new posts every Thursday, where I’ll be backing up some of the assertions made in Beyond Legacy Code: Nine Practices to Extend the Life (and Value) of Your Software with additional information, tips, and strategies to help us all come together and once and for all move Beyond Legacy Code.

—David Scott Bernstein

July 16, 2015

Seven Strategies for Continuous Delivery

Continuous delivery is the single most important step in agility. Regardless of whether you do big releases or not you should always build software incrementally so it is always in a releasable state. Why? Because the only way to know if code will work in a system is to test it in the system. This is at the very core of XP and Agile. Here are seven practices for continuous delivery.

1. Think about automation from the very beginning

Project automation can’t usually be an afterthought. We have plan for automation in our design from the get-go. We do this by validating our architectures and designs are testable and easy to automate. This involves isolating business logic, building pluggable components, and making code within each component simple to understand.

2. Implement a one click build

The build has to be easy to use. It has to be fast. It has to provide good diagnostic information if something goes wrong, and most importantly, it must be trustworthy. As soon as new code is checked-in to the repository from a developer’s working copy of the system, the build automatically runs along with a full suite of unit tests to validate direct dependencies. If that passes, the new code is automatically promoted to the build server and either the entire build is run immediately or queued for later and a partial build is run immediately.

3. Write testable code

Of course, the key to building an easy-to-automate system is to write testable code. Too often, developers write tests after they write code only to discover that their code is untestable and has to be rewritten. Developers should avoid practices that yield untestable code.

4. Write the test first

The best way to write testable code is to write the test first. By writing the test first and then creating production code to make a failing test pass, we are assured of always writing testable code and end up writing code that’s more focused and succinct. When done correctly, test first development helps developers write cleaner code with less effort and more support.

5. Strive for 100% test coverage

Another advantage of doing test first development is that all production code we write is inherently about making a failing test pass so we always get 100% test coverage. If you don’t think trivial code should have unit tests then I won’t argue with you but complex code or code with multiple paths through it should be covered by tests at the unit level.

6. Remove human intervention

The key to doing continuous delivery successfully is to remove all manual processes from validating a release candidate. When we can do this we can drop the cost of validating release candidates to nearly zero and the build becomes a rich source of instant feedback for the team that they use all the time.

7. Give back control of releases to the business

Continuous delivery doesn’t mean you have to release all the time, it means your system is always releasable. When new versions are released should be a business decision based on sales cycles, maintenance plans, and other business factors. When we practice continuous delivery we are giving control of when we release back to the business where it belongs.

Continuously delivery fundamentally changes the dynamic of developing software and turns the build into a source of rich feedback for developers. If you’re building software incrementally then code should be integrated as it is being built. The way to reduce the risk of building features is to integrate them into a working system as they are being built.