Anna Blake's Blog, page 37

August 12, 2019

Photo & Poem: I Cannot Know

We became strangers. I thought I knew her so

well; that place just back from her ears where her

mane flips to the other side. Her slow half-closed

eye resting in speckled shade, head low to the

flank of a gelding. Her outline in moonlight blue at

the night feed, the horse from my childhood dream

in my own barn, as solid as hooves on dirt. But in an

instant, she swung her hind around with a hard snap,

head high, a sudden snort clearing her nostrils as she

dropped the weight of domestication, her hooves sliced

the air, her weightless body wild to instinct. The herd

lifted their heads from hay in metal feeders, ears cocked,

muscles ready for flight, heeding her alert. A scent on

the breeze? Something I cannot know that she cannot

ignore, an emergency message from ancestors warning

of danger and betraying any certainty I had imagined.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Photo & Poem: I Cannot Know appeared first on Anna Blake.

August 9, 2019

Calming Signals: Trust Above Training

It was my job to haul him to his new trainer. He was a bright young gelding, some would call him hot, as if having too much anxiety was just how some horses are naturally. I’d call him low on confidence, not a crime in a young horse. He pranced a bit on the lead, I told him what a good boy he was, and then we stood behind my horse trailer. His owner so certain that it was going to take a while that she pulled up a chair, but he was curious, I was breathing, and he walked right in. After all, you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure out what it means to stand at a trailer’s open door.

At the new barn, his trainer took over. The gelding got in trouble for his energy. He was eternally wrong, so the corrections were endless. It was soul-killing but also common training practice. Some horses of other breeds might just shut down to stop the fight, but he didn’t even know how to try that. He was particularly anxious when confined, so the trainer left him tied up. It wasn’t considered cruel; just let him fight with himself was the theory. He was tied in a stall, no water or hay all day, until he stopped being fussy and then he was released. Ulcers roared inside him, pain contributing to his “bad behavior.”

It’s a method that might work for some temperaments, I suppose, but not this horse. Day after day, tied short and dancing all day long, his hooves never still, always trying to run but not able to get away from this stall and these predators. When he was on the lead, he was circled as punishment. The trainer said if he wants to move, make him circle until he is tired and then push him farther to exhaustion. But the horse was filled with adrenaline. He didn’t give in, but instead, he got hysterical like a toddler in the grocery store who can’t stop crying.

When the farrier came the horse was like a kite, and the owner circled him each time he moved a foot. The horse got more frantic, he couldn’t tell if the circling made him anxious or if the humans did, but now he circled when he was anxious. I intruded, fearful that the farrier would quit all of us, and his frustrated owner was glad for the break. We breathed and this young horse was praised when he tried to stand. Not perfect but his feet got done, without the circling groundwork that always scared him.

The humans were sure their training methods worked on all horses, so they doubled down. The methods that didn’t work on the ground, didn’t work in the saddle either. I understand what they thought they were training, but what this young horse learned was that people were not to be trusted. A misunderstanding, but he became more unstable, and riders came off. He never tried to hurt anyone, he just wanted to escape us, and he was even kind about that. Hollow, in pain, and so constantly anxious that he seemed crazy.

Why do we think horses are crazy when they don’t trust us?

What was missing in his training, besides knowledge of how horses think? No one listened. They knew he was disobedient, but the messages he was giving went unheard. The louder he got, telling us that he was no threat, that we didn’t have to fear him, the more we pushed him. People had the idea that they’d ride through it, keep applying pressure and eventually, he’d give in. He didn’t. Something was wrong, either the training or the horse, and everyone agreed it was the horse. Even this young gelding, sealing his own fate.

Meanwhile, there was no inter-species conversation. The trainer mainly lectured in that method of training because it’s easier than trying to understand how horses think. Knowing that a frightened or anxiety-drenched horse can’t learn should be common sense.

“I can’t unsee a horse’s calming signals.” That’s what clients say; behaviors once disciplined are now understood to be signs of stress. Not that reading a horse’s emotional state is new. Classical dressage trainers have been teaching it for centuries. It’s our foundation; that a horse must be both relaxed and energetic to be comfortable under saddle.

I think the problem is how humans think about training. If it didn’t sound so lame, I’d say we put the cart before the horse.

We think training will make a horse trust us, that techniques are the most important thing. We try one approach and if we don’t get the result fast, we push harder and scare the horse into a reactive answer. Or we quit and try a different approach, with so many contradictory ideas in our rattled minds that our horses are confused by our inconsistency. Finally, the two of you have something in common, at least.

Anxiety and trust do not cohabit; they are oil and water.

I believe the more enlightened path in training is all about creating a safe place for horses. We must prioritize calming signals above any training approach. Their emotions over our desires and the conversation with a horse above a demanded response. A training method is only successful if the horse comes away with confidence. Trust grows when a horse feels safe, when he is free of anxiety.

Want a concrete example? Say you’re riding or working in hand. An obstacle appears, perhaps as simple as a tarp on the ground, but your horse resists it. What’s your first thought? Do you leap into action with a technique to “fix” him by pressuring him forward? Did you cross a line and become adversarial? What are your emotions doing? Is there an edge of something your horse would read as anxiety because you’ve judged his resistance as wrong? Is your anxiety a cue to him?

Training techniques work when they support our relationship with horses, but only when we are each a partner, not a slave. I mean slaves to our natures: the age-old posture of humans becoming aggressive and horses warning us they are no threat. Predator against prey. Training techniques versus calming signals. We’ve got it turned backward.

Responding to calming signals is more important to a horse, and ultimately us, than any technique to make a horse do what we want. Resist becoming adversarial with horses. In that instant, slow down and listen. Horses are happy to return the favor and stay in the safe place with us.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Calming Signals: Trust Above Training appeared first on Anna Blake.

August 5, 2019

Photo & Poem: When the Sunset is Through With Me

The sunset plays me. In the heat of the day,

colors are flattened by glare and searchlight

bluntness, work taken on, tasks finished.

But when the sunset looks at me sideways,

flirting through the clouds, changing expression

in each instant, I come stumbling out on the

porch, fumbling with my glasses, my camera,

knowing before I’m focused that the sky is

teasing me. It’ll look small in the viewfinder,

flat in the photo, but scurry, I do, because I

must keep the color. To the west, such sweet

pastel tones, his whispering conversation thrills

each prairie grass, the scars on my skin go smooth,

as feather arm-hairs lift, but I sense something

bearing down fast behind me. Pulling my eyes

from the syrupy horizon back to the east,

dominating as loud and brash as a marching band,

purple and orange, trumpets and drums, slash

the sky. Devoured by color in light; when the

sunset is through with me, there will be nothing left.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Photo & Poem: When the Sunset is Through With Me appeared first on Anna Blake.

August 2, 2019

Calming Signals: Do You Tease Your Horse?

There was a time that I had a basset hound named Agatha and a bunch of friends with toddlers. It was hell.

See it from Agatha’s side. Toddlers are short and take uneven steps, moving more like a prey animal than a human. A tipsy bunny. And they are sticky-sweet, sometimes wearing a soiled diaper. What luck, all the best smells in one place. Usually, if they have a cookie in one hand, there’s a second cookie in the other, but both soggy with baby spit and only an un-athletic hop above nose-level. You can pick off one of the cookies and go eat it, and toddlers are so simple-minded that some think it was their idea to “share.” Silly. Even if they’re crying, there’s a decent chance you can go back and get the second cookie. It’s still right there in their sticky fingers. Toddlers are literally low-hanging fruit.

See it from the toddler’s side. Dogs are like stuffed toys that move. Spellbinding but if toddlers even have a side, they aren’t old enough to articulate it. That just leaves that eternal stare between a certain sort of parent (those without dogs) and an equally certain sort of dog owner (those without kids.) Each believes they have the high moral ground.

Growing up on a farm, I was told that even if I got bit, it was my own fault for teasing the dog. Whenever animals are shown more respect in the past than now, it’s interesting. Have we lost some understanding about what teasing means?

Years ago, I had a rescue Doberman, who came to me malnourished and later nipped a little girl in the face. She was trying to kiss him while he was eating. Clearly, there was an adult fail here. The girl was scared but okay and her dad very apologetic. I also understood on an even deeper level how much of a job it is to protect a dog with issues. I could have lost him for my foolishness.

But how to explain to children, or adults who act like them, what it means to tease an animal?

So often we see photos of toddlers laying on top of dogs pulling their ears while the dog has tense eyes with whites showing. The intended humor of donkeys “smiling” when they are being teased with treats. Horses who are “kissing” when it’s about a nerve response. Horse’s pinned ears, wrinkles around their eyes, while working at “liberty.” Horses who close their eyes to pull inward from the intense proximity of a human while we think they “love” us.

I have so many emotions about teasing animals that I turned to the dictionary for a straight definition. Tease (verb) to make fun of or attempt to provoke (a person or animal) in a playful way. What a clean, nearly terse answer, but it stirred me up, too. This sentence has two words that seem to fight; provoke and playful. That’s the question. Is it okay to provoke an animal if we mean to do it playfully?

I know a handful of equine bodyworkers who hate carrot stretches, where we encourage a horse to stretch around by holding a carrot back by their flank or down between their front legs. Then, we usually ask for a bigger stretch by moving the carrot farther away. Bodyworkers say that horses, whose instinct is to graze almost constantly, are so food driven that they frequently torque muscles or even injure their backs in an effort to get the treat. Is this teasing?

Zoos might be the most complicated question of all. We have a nationally ranked zoo here in Colorado, built on the side of a mountain. You have to be in decent shape just to walk the hills and they work so very hard to create the best habitats for the animals. For so many people, this is the only chance they will have to see these animals, and many are then inspired to go on working for animal causes. At the same time, many of us don’t like to go to zoos. We don’t like to see the anxiety in the animals there. At our zoo, you can feed giraffes healthy treats like lettuce, but there is a pen with a few separated from the herd. Their behaviors looked just like ulcer symptoms I’ve seen in horses. Gorillas sit on the green mountainside looking at human children squeal and wave. When they meet our gaze with a perimeter between us, are we teasing them?

Enter the knowledge of calming signals. The phrase was coined by Turid Rugaas, who is a Norwegian dog trainer. It refers to body language dogs use to express their feelings. Much of the dog language is shared by horses, but once you become fluent in calming signals, you can see similar signals in most species. It’s the biggest game-changer for anyone who works with or loves animals. They have been telling us everything since the beginning of time and lots of us knew that. Now we have research and data that confirms their ability to communicate with each other, and if we care to, we can learn that language, too. Warning: once you learn to read them correctly, you can’t unsee it.

Calming signals are literally how we learn to see the animal’s side. They give you the opportunity to look with new eyes at body language and behaviors that are very familiar to us, but now can be understood to mean something different than we thought.

It bears repetition: Tease (verb) to make fun of or attempt to provoke (a person or animal) in a playful way.

It’s still a good definition but why do I feel anxious? I remember a gang of boys at my grade school who ran holding hands, and circling a girl, to take her off somewhere. We were scared, even after being told they were just “teasing” us. Was it playfulness? Do little girls lack a sense of humor? Or is the word bully missing in that definition?

But we don’t do that! We love animals. We love to provoke a reaction from them, to prove to ourselves that we don’t hold them prisoner like a zoo. It flatters our ego that we are the object of their affection, which sadly is starting to look more like anxiety in the context of calming signals. Not to mention that looking at cute animal pictures is almost entirely ruined.

When we know more, we can do better. What do we see now that we misread before? What would we choose to bring to our own animals, given the opportunity to understand them better?

And for any naysayers who may accuse me of trying to start a #metoo for animals. No worries. Animals have done it with calming signals all along.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Calming Signals: Do You Tease Your Horse? appeared first on Anna Blake.

July 28, 2019

Photo & Poem: Sentient

Long in the tooth, people say. Gray hairs

dusting his temple, this gelding plays the

part of good uncle, passers-by tickle his

nose to show their familiarity, unaware of

of the memory that kind of touch brings this

stoic gelding who remembers too far back,

too sad a time. Past his prime, people say.

No, he carries his guarded history with him,

each era of his life in each swing of his leg,

power and pride, to distract from a slightly

frayed nerve, small sparks in a wet wound, his

secrets his own to hold behind a discreet eye.

Offering himself, even now, as is. For you.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Photo & Poem: Sentient appeared first on Anna Blake.

July 26, 2019

Aggressive or Assertive?

She was a breathtaking draft-cross mare who I met at Duchess Sanctuary this year. There was just a presence about her that made it impossible to look away. She came up for a closer look but didn’t pander. Standing her ground, there was nothing she wanted from me and I asked nothing of her. I haven’t always had great female role models in my life, but I’ve learned so much from working to understand mare behaviors, that I translate in a somewhat unscientific way, into my experience. This mare was someone; the whole herd had an undeniable strength about them. Intelligent and curious, just the very things I admire most.

I was asked about the difference between aggression and assertiveness. It made me smile; it was a horse training question but a dinosaur feminist like me will always hear those words with nostalgia. Could women be assertive without being called aggressive? Historically women were valued for being quiet and demure with good domestic skills, made even better if you played the piano. Things that some horsewomen flunk out on before we’re even grown, because if you were like me, you wore jeans and learned to drive a tractor before starting grade school.

Classical horse trainers, like James Fillis, wrote that women had frail temperaments, only fit to ride the oldest and dullest of horses, but before you call him misogynist, he also wrote that Italians were too emotional to ride. He apparently felt fine with blanket generalizations.

We almost instinctively judge temperament in people along with their message, and usually women a bit differently than men. A man might be called passionate while a woman might be called temperamental for the same behavior. Now compare your descriptions of Arabians and Quarter Horses. Of dressage and trail riding. Word choice reveals our preferences and prejudices.

Words like aggressive and assertive may fall into a similar category. Are these words interchangeable? I always hear the word aggressive to have an emotion attached, like anger, insecurity, or frustration, whereas assertive has more of a feel of stating your point with clarity, purpose, and perhaps bluntness. Truthfully, both create some level of social discomfort.

I enjoy a spirited, assertive talk; one filled with passion and clarity that challenges my mind to think more deeply about my beliefs. Recently, I listened to a speaker who had a passion for their topic, but somehow it came across aggressively. Listening to that speaker felt a bit like being sent to the principal’s office for a lecture and maybe a paddling. I checked the others sitting around me. We were adults squirming in our chairs; we looked away, checked our phones, or stared at our laps. We acted like we were in detention. The calming signals I saw humans use in that situation were more instructive than the information that I resisted hearing.

In the practice of training horses affirmatively, theoretically, we don’t get aggressive. We shun trainers whose horses show the whites of their eyes or have tense, ringing tails. Again, calming signals seen in the horse’s body language tell the truth, perhaps more than the words of the trainer. We allow ourselves a bit of pride. Instead of fighting with our horses, we aspire to negotiate.

There are certainly exceptions, but if I were to make a Fillis-like generalization, frequently women are passive-aggressive. Perhaps we might have learned it from our mothers, “Honey, are you really going to leave the house looking like that?” Or, “Well, bless her heart, she’s as mean as a snake, God love her.” What does that even mean?

“A passive-aggressive rider keeps all the fighting inside. It starts reasonably with the fear of the things a rider should fear. And there’s no shortage of true danger to consider. Then anxiety creeps in; we think about everything that might happen on the horse but also worry about how we will be judged, especially in our own minds. Then most of us like a little more control than we can have on a horse. But that’s wrong, so we stifle our fear and anxiety. We pretend we aren’t frustrated and that we don’t get angry. We say we have no ego, but instead, we have an unsteady center of worry, anxiety, and regret. With a dollop of compulsive apology on top, and the cherry of self-loathing that we all learned as teenagers.”

The biggest challenge we have as riders is to find the middle path in this world of chaos and extremes. Where is the sweet spot between being an aggressive monster and a passive-aggressive bowl of worried oatmeal? The balance between blustery non-stop lecture-training and listening so hard that we are silent non-participants?

Both extremes aren’t helpful to horses and they don’t care much about word choice, they read body language. Humans can be a bit contradictory; we smile when we aren’t happy, and that’s just the start. Word choice should matter to us. If we could tack our behaviors to a word, maybe we could demonstrate more consistency.

I believe how we cue is more important than what we cue. In dressage, we believe the art of riding exists in a calm and energetic transition. Most horses don’t have all that much opinion about trotting but they do care how they are asked. If the cue causes fear or anxiety in the horse, he’ll be tense and physically uncomfortable. With such a jagged cue resulting in an unbalanced gait, a horse is more likely to spook or injure himself with a bad step. If the cue is too mumbled, mushy, or vague it’s possible they’ll be confused and just ignore it. Then if we nag it just dulls the cue more. Nagging demeans both the horse and rider. The horse might drag his toes to a resentful trot.

Clarity is kindness. I think horses are looking for an honest request. They don’t understand indirect communication. Ask clearly, with bright energy but no extra emotion. Just a calm declaration, “Walk on,” with the confidence in yourself and the horse that you don’t need to repeat yourself. Let your word stand with no apology as if bluntness was a virtue.

Consider that regal mare again. I’ll call her assertive. I won’t pretend to be her, but I’ll strive to match her natural energy.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question.

The post Aggressive or Assertive? appeared first on Anna Blake.

July 22, 2019

Photo& Poem: Go Fish

Mom took us kids in the station wagon to the

church bazaar. Homemade women’s goods for

sale; boring cross-stitched aprons, jars of choke-

cherry syrup, crocheted doilies as fine as snowflakes.

A long table with lemon meringue pies and scratch

yellow cakes with chocolate frosting lined up for

the cakewalk. I walked past game booths, a ring toss

with holy card prizes, all the way to the booth where

I was sure to win. Go fish, a white sheet hung

across the booth, construction paper fish randomly

pinned to it. I traded my only nickel for a fishing

pole with cotton string, a clothespin tied to the end.

I cast over the curtain on the second try, holding

my breath until the string jerked twice. I retrieved a

doll-sized tea set with silly flowers. The boy next

to me was equally unhappy with his plastic horse.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Photo& Poem: Go Fish appeared first on Anna Blake.

July 19, 2019

Affirmative Training for Colts and Fillies

Foals are irresistible. They are precocious and lively; they cavort and air gallop and sleep flat-out. When they wake up, they’re an inch taller and even more curious about the world than before their nap. They have newborn piaffes and sliding stops. They jump like frogs. They are a fresh start, a whole new life. Who doesn’t want that?

My first professional training job was at a breeding farm. I had a flock of weanlings, some feral. I had the time of my life introducing them to leading, picking up their tiny hooves, making trailer loading a game. In the years since then, I’ve worked with mostly adult horses, many who don’t lead or feel safe enough to pick up their feet or flatly refuse a trailer ride. When healthy midlife horses are re-homed, it’s usually because of training issues. Some horses land with a patient new owner, some get worse through several owners, and some fall through the cracks, their lives disposable. I do know they were all brilliant foals.

We had a plan. We were challenged by our last horse so we want to start a foal, confident that we can handle problems of our own making. As if those problems are easier. Or we want a youngster so we can have the horse longer. Clearly a newbie, human plans are confetti in a barn. Or we want a horse to grow up with our kid, one of the most dubious parenting choices ever. Some of us just want to try.

If it was easy to start a youngster, we’d all have flawless riding horses and we could squander money on new boots instead of supporting rescues. It isn’t just backyard-bred horses started by novice riders that get into trouble; it’s famous trainers turning out horses no one can ride. It’s the knowledgeable Quarter Horse owner who ends up with a Thoroughbred who turns their toolbox inside-out. It’s an imported warmblood with impeccable bloodlines who can’t live up to our hype.

All were beautiful foals, perfect in every way. No blame intended, just to say that training is an art that comes with a serious responsibility. Their life is at stake, nothing less.

Still, I understand about fillies and colts and humans who can’t say no, so here are some thoughts about starting a young horse.

Many farms wean foals at about six months old. Statistics say the vast majority get ulcers; 98% within two weeks after weaning. Take this part seriously; pain will make the transition much harder for the foal and could contribute to a life-long gastric issue. Are you certain that your last horse wasn’t struggling with gastric pain? Can you leave the foal longer with his family or perhaps bring the mare home, too, for an extended stay? Can you give the foal gastric support? Patience with your new horse might start with waiting longer to bring him home.

Let’s define training as gathering good experiences where the horse feels safe. Safety equals trust. Now, replace the word training with the word nurturing and hold yourself to that standard.

I want this young horse to have a calm strong mind, so regardless of what I’m teaching, I will model calm and quiet conversations. I’ll laugh because it relaxes both of us. I’ll challenge him but never frighten him. I’ll keep breathing, teaching myself as much as him, that a cue to breathe is a cue to relax. I’ll trust breath above training aids because connection happens, not with flags and spurs, but inside warm exhales

Most important of all, I know that when a horse is curious, he builds neuropathways which literally create a strong mind. Giving him time to think means he can stay in his parasympathetic nervous system where he can make good choices and be rewarded. Curiosity grows into mental health which turns into confidence and a confident horse will see challenge as a fun game. I’ll always prioritize curiosity over a training technique because if a horse is always frightened, flooded by erratic, confusing cues or intimidated by threats and corrections, he will stop being curious. He’ll shut down; pull inside himself as if playing dead. If we don’t listen and keep pushing, eventually he’ll get almost hard-wired to respond with his flight or sympathetic nervous system. He won’t be reliable because we’ve sacrificed trust for fear-based obedience. When you look at it that way, pushing him too hard creates a real mental dysfunction. We know horses like that, don’t we?

I’ll remember and do better for this young horse in front of me. Youngsters can be so bright and quick; they can make you think they’re capable of more than they are. Then we get excited that they’re such geniuses and ask for just one more repetition. A baby horse will try. We know we should go slow, but it’s hard to let it be good enough. When the youngster hits a wall, we think their overwhelm is resistance. “You know how to do this!” we threaten but maybe that day he can’t. As an apology to generations of homeless horses, if what I’m asking isn’t working, I’ll stop. I won’t repeat the useless cue louder. I’ll make peace and let it go that day. I’ll find a better way to ask because training requires us to be more creative than demanding.

Youngsters are imperfect learners. They can be loading fine and then get a fright and refuse. They can take a canter cue or lead from behind brilliantly one day, and be hopeless the next. We must stop seeing immaturity as a failing on the horse’s part. Ask for small things in short sessions. Allow him to move out; moving is thinking. When he comes to stillness, he understands. Praise generously and stop when both of you hungry for more.

Behaviors come and go, but I won’t let myself make one misstep an issue for my horse by drilling or over-correcting. If he makes a small effort, that’s enough. He was curious so let him figure it out. Since I rewarded his try, he’ll feel confident to try more the next time.

It’s years before a horse becomes dependable. Affirmative training is hoping for the best but accepting some days fall short. One lesson can’t be more important than another, just as one rough day can’t ruin either of you. Let it go. See every moment not as the work of training but an opportunity to be worthy of a horse’s trust.

How to start a young horse is no different than how to rehab a troubled horse or connect with an old campaigner. Never lose sight of them as foals. Remember their true nature; the things you love about horses. Then, say yes to remind them of who they were born to be.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Affirmative Training for Colts and Fillies appeared first on Anna Blake.

July 15, 2019

Photo & Poem: Faraway Friends

I would show you the adolescent Canada geese

on the pond. Better behaved than we ever would

have been, they stay close, like Catholic school girls

in prim uniforms between their parents in church.

We would give them names like Cecelia and Mary

Margaret and Bridget, us standing by the donkey,

scratching his ears and thinking the other was smart

and beautiful and funny, without recognizing our

similarity. Then, I’m walking your memory back home

from the far side of one day and you’re walking mine

back from the next. So unwilling to part that we try

to make peace with the constant wanting of ordinary

time, by holding the other’s voice in our ears along

with a small ache; the price paid for the utter luxury

of a friend who shares the same moon, sunrise or

twilight, while caring for horses who will never meet.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Photo & Poem: Faraway Friends appeared first on Anna Blake.

July 12, 2019

Brain Science as a Training Aid

It was a two-day-long science class and we were promised a brain dissection. I signed up immediately and have had the weekend marked off on my calendar for months. I can’t imagine you don’t want to hear all about it.

Our instructor was Dr. Stephen Peters, (Psy.D., ABN, Diplomate in Neuropsychology) a neuroscientist, horse brain researcher, and co-author of the book, Evidence-Based Horsemanship. Mark Rashid and Jim Masterson each gave input over the weekend as well, but in the best possible sense, we were all there to learn. It was a wonderful group of profoundly interested horse people. You could tell because it’s summer and we were inside all day.

We got warmed up Friday night with slides of human brains, both healthy and with dementia. The next morning, we dove into the parts of the equine brain and what they do. The presentation included photos of horses getting CT scans and MRIs, images that made me want to jump up and do a few fist pumps! It’s the basis for The Cambridge Declaration of Consciousness in 2012 when science confirmed what our intuition knew, that our animals have conscious awareness and emotions.

We went on to talk about sympathetic and parasympathetic aspects of the autonomic nervous system, and neurochemicals like dopamine, serotonin, and those misunderstood endorphins. All my favorite words, along with new words like dendrites, the neuropathways built when a horse stays in his parasympathetic state, when given time to be curious and think. Then the resulting dopamine reward, strengthening his self-soothing abilities. That might be the scientific description of confidence. It’s better science compared to a fear-based approach that sends the horse into a flight (or sympathetic) response. Affirming to hear, isn’t it?

Then the amygdala that never forgets trauma, a condition I work with so often in horses. This is the cup that holds all the issues of fear, pain, and survival of the damage from humans thinking they can “desensitize” a nervous system designed to react. In my mind’s eye is the large herd of damaged horses that stays with me; all the client horses I’ve worked with who don’t respond the way we’d like. We don’t have nearly the amount of research we need in the area of brain dysfunction.

Helping horses is part science and part art, but we will never be able to communicate effectively with horses until we understand how they think.

Then, just when you’re nearly overwhelmed from hearing big words and trying to fit instinct, fear, and memory together in a puzzle of behaviors, experience, and training, Dr. Steve says something so simple and obvious that your chin drops. “It isn’t possible for a horse to respect a human; they have no frontal lobe.” Huh. Logic.

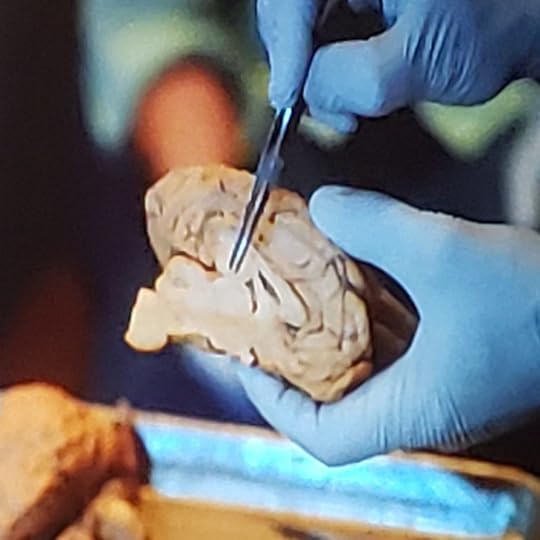

Sunday morning was the dissection. Now is a good time to tell you that in biology class, I was the one hyperventilating with my head between my knees on frog dissection day. I probably would today, too. Herpetophobia, I’ve never been good with reptiles.

Horses are a different thing and I’ve pushed in at every chance, assisting vets with injuries, surgery, and euthanasia. Over the years, my emotions about blood and guts have had to settle, so I could do the best for the horse. But there was no life in this brain, so my emotions rested easily and let me listen. Gosh, that sounds like I managed to downregulate and stay in my sympathetic nervous system and learn. What does that remind me of?

Some participants were shy about this part, but many were drawn in as I was. Rubber gloves were passed around, as I focused, craning to see as Dr. Steve removed the meninges, the connective tissue covering the brain and spinal cord. It was a darker color and so tough, with no elasticity.

The brain itself is a narrow range of off-white colors. I didn’t expect it to have pastel-colored sections like book diagrams, but I was so struck by its cauliflower-colorlessness, for all the rich and intense activity that had gone on inside. Dr. Steve dissected the brain in half and described each part clearly. The olfactory area is separate from the other senses, that makes sense. By this second explanation of the parts of the brain, the words were more familiar and understandable but at the same time, they became more mysterious. Paper plates were passed with sections of the brain and we were encouraged to touch and hold them.

By the time the cerebellum reached me, many others had held it already. It was cool, no hint of blood or trauma. It was dense and somewhat flexible but not rubbery. There was a wonderful cohesive quality to the material. Holding this small tangerine-sized oval in my cupped hands, I was unprepared for what I felt. My breath shallowed as a huge wave of emotion exploded. Goosebumps, and love for this hunk of “cauliflower” resting in my palm. Humans romanticize about the heart of a horse but for me, it’s always been the horse’s intelligence, his awareness, and how he engages the world. This sacred weight in my hand was the physical home of all that I love about horses, the place where exterior actions become mental reality. It’s the place I want to know most. Holding it, detached and vulnerable, I was gobsmacked to the core, meaning in some off-white “cauliflower” part of me.

Sure, I’m a geek; a horse-crazy girl who spent the weekend scribbling notes instead of filling out my Medicare paperwork. As a professional I need to know this stuff but why should science matter to you?

For the quad-trillionth time, my favorite Xenophon quote from 430 B.C., “For what the horse does under compulsion … is done without understanding and there is no beauty in it either, any more than if one should whip and spur a dancer.”

It’s the confluence of science, Xenophon, and equine calming signals, along with our own intuition, joining to confirm the art of affirmative horse training.

Some of us have been bullied by trainers who think horses are capable of diabolical plans to trick us into letting them win. Or by railbirds who ridicule us for ruining our horses by training “like a girl.” It can wear you down but stand tall.

There is a shift in paradigm happening in understanding and working with animals, and women are on the cutting edge. Lead with confidence because we’re right about this.

Bullies and naysayers, beware. Brain science has our back.

…

Anna Blake at Infinity Farm

Want more? Join us at The Barn, our online training group with video sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and so much more. Or go to annablake.com to subscribe for email delivery of this blog, see the Clinic Schedule, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

The post Brain Science as a Training Aid appeared first on Anna Blake.