Anna Blake's Blog, page 21

May 7, 2021

Take a Cue from Your Horse

He was a bright young gelding. Alert, athletic, and so willing. One day he would become the kind of breathtaking dressage horse that his sire was, I hoped. It would be years before he’d be started under saddle, but it was the perfect time to start arena work. Did you just seize up a bit? Does taking a young horse to the arena sound like punishment? Do you shake your head, knowing dressage is all micromanagement and dull repetition? Don’t feel sorry for him yet.

We’d enter the arena and pause. He knew what came next and his eyes got brighter, but he stood still as I undid the buckle and paused with the halter dropped off his muzzle but still around his neck. Another moment of wonderful anticipation. Then I’d drop the halter and pause again… his head was up and ready. Then one cluck. He’d bolt away, gallop the long side, and stop at the far end of the arena to snort. By then, I had walked to the middle of the arena and he’d turn to gallop the long side again with loud cheers from me. If it was a good day, he’d buck a few strides to get the kinks out of his back and the crowd (me) went wild. And he’d slow to a trot that had more the feel of a prance with his back lifted and his neck relaxed but high enough that he could push his chest out, good boy! Some days he’d drop and roll, and then leap to his feet, a gallop in the first stride. Now that’s a transition, whoop!

He’d canter to me and halt. This game had two players. I’d go as still as he was, and cluck. Game on again, he’d run, and I’d clap. What if the arena was the place where no one ever got punished but all the best games happened? Once he’d sprayed the entire arena with exuberance, and I had warmed up my lungs sufficiently, things slowed down. Our groundwork included taking turns mimicking each other, reversing in a spontaneous dance of movement and halt at liberty. Pauses, leaps, and spins that one of us did more beautifully than the other, but that was the goal. I wanted him to feel beautiful in his body. No whips, no ropes, no treats. Just a shared conversation, the only word was yes.

One morning, after running through everything I could think of, I needed to catch my breath. My eyes dropped to his left knee, just for a pause, and that knee rose from the ground and slowly extended, holding in midair. Two things happened then. I cheered his brilliance and I realized I needed to up my game. The line between horse and trainer got blurred in a way that I wanted to continue.

How many times do we approach a horse with the goal of manipulating his behavior? Some of us flat-out want total control. We bark orders and destroy the brilliance of a young horse when we could get a dirt bike and be happier. But not you. You want a partnership (as long as you lead.)

The horse must behave so we begin making small adjustments. We don’t pick a fight, we just correct him for not standing still, we back him up, we jiggle a rope. Now we’ve trained him to jig. You can tell because it’s what he’s doing. We crowd into his space and then demand he get out of our space. He tries to figure out what we want. Stand still, we say, as we cue him to move. He pauses and we watch closely so we can pounce when he moves again. As if training was a process of elimination, we tell him he’s wrong until he quits trying. Nothing harsh has happened but there’s no opportunity for brilliance because we’ve dumbed him down, his eyes in soul-killing, unreliable surrender.

Why do we do it this way? It’s simply easier to say no. We feel more secure when we’re correcting the horse. It allows us the illusion of control. We fault what’s been done instead of inspire the next great thing.

Training a horse begins with a choice for the human. Who do you want to be to this horse? What do you bring in your body language? Can you offer him something that feels good? Because I want the day to come that we move together in brilliant, relaxed unison, I won’t fight now. I’ll stay on his side. Horses understand the value of getting along. We can trust his intelligence enough to not talk down to him, but rather let him feel the confidence of getting it all right. Most importantly, we can prioritize his willing attitude by not adding to his anxiety. Instead, ask a question and listen patiently, holding for the possibility that he might offer a better answer than expected.

Flash forward a few years. Our rides still start by him galloping at liberty, with his saddle on now. He shakes it all out before the fun at the mounting block. He’s young and struggles with balance in his canter depart. It’s natural, the canter isn’t the solid, two-feet-on-the-ground gait that a trot is. The canter is naturally unbalanced, without a rider. We don’t drill it; it would be a truly stupid mistake to rush a canter.

Instead, I was suggesting that a longer trot stride might feel more relaxed than a shorter one. And by that, I mean I was focused on myself, staying in rhythm with him, balanced in my stirrups, carrying my body lightly so he might lift his back. I’m focused on riding the up-stride of the trot rather than the down-sit, thinking up, up, up. Then I listen to him. He answers with the sweetest canter depart ever, but because I was aware of my body at the time, I noticed a small movement in my inside hip bone. It was as if he said, “Feel that place right there? Just lift that a quarter-inch and leave your legs out of it. Less is more, Anna.” That was it. No stress, no friction. He taught me how to lift to a canter as he does in the pasture. It felt absolutely euphoric. And go figure, it’s worked on every horse since.

I like to think this particular horse was special. He wasn’t, it was just his luck to show up when I was able to listen better. No pretend connections or claims of artificial partnership. I was receptive to his intelligence. Instead of a trainer and a horse, we became explorers.

It’s his birthday this week, this beautiful horse who is long retired. It’s all play now that I understand the game. He still pulls to the arena. I cluck once, the invitation to say yes. I wouldn’t think to correct him. I’m too busy listening so I can ask better questions. We’re all about what’s up ahead.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Take a Cue from Your Horse appeared first on Anna Blake.

April 30, 2021

Affirmative Training: A Cowboy Walks Into a Bar…

A cowboy walks into a bar. He’s dusty, fresh from the barn. Shuffling his feet, keeping his eyes low, he crosses the floor. Voices stop as the cowboy collapses on a stool by the bar, pulling his hat off with one hand and burying his head in the crook of his other arm. The bartender smiles and sets a whiskey down in front of his friend. As the cowboy slowly exhales and lifts his head, his eyebrows in a tight line.

The bartender asks in a soft voice, “How is that new colt doing?”

The cowboy’s eyes fill at the kind words and he can’t the emotion hold back, “So good. He tries really hard. I’m going slow and listening to his calming signals,” the cowboy says, tears spilling down his cheeks leaving muddy tracks. “I just don’t want to mess him up.”

Wait, maybe it wasn’t a cowboy. Not a sober one, anyway.

Now that I think on it, it wasn’t a cowboy after all. It was a woman. A friend who has a passion for horses. And no, it wasn’t a bar, it was your kitchen, and you made her tea.

Or it was you, alone with your passion, and you made yourself tea while you worried about ways you might fail your young horse. Or fail the rescue-rehab in your pasture with frightened eyes and a stiff shoulder. Or fail that old campaigner, long retired now, but you wonder again if he has another cold winter in him. The bottom line is you care too much and you know it. Can worry be affirmatively focused? We do our best thinking in a pinch. It would be a shame if self-criticism blinded us to worry-fueled solutions.

Maybe you think the railbirds are judging every move you make. They can be real folks wearing celebrity-trainer hats, trying to pass by parroting things that sound tough, saying you’ll spoil that horse. They can be imaginary railbirds, who live in your head and are even worse. They sing-song in your ear, “You pansy, are you afraid? Can’t you make him do it? Show him who’s boss.” The imaginary railbirds say the meanest things.

So, you put the cup down, grab your gloves. No, you won’t start that colt at two. No, you don’t start working with that rehab horse right away, you give him time have time to settle in. And because it’s always better a day too soon, than a week too late, you won’t let that old gelding suffer. You do the right thing, staying true to the horse.

You will be the first to take the blame for your horse and the last to want to draw any attention to yourself. You patiently work through problems with your horse, not that you’d ever brag about it. And then, as if it was nothing, you practically forget because you are working on the next good thing, worrying that you will fall short again. If we take care of a horse’s primary needs, are patient and go slow, is it even possible to fail a horse?

In our world, it’s considered good manners to praise the horse on a good day, and for the rider to take the blame if things go sideways. There is nothing worse than watching a horse get punished for a rider’s frustration. So yes, take the blame, but if in this process, as we slouch and mumble about our shortcomings, what does the horse see? We act humble for the humans nearby, as if horses don’t keep us humble without us acting it out.

You’d think that confidence was the exact same thing as arrogance, some sort of poison to be avoided. Or like there is some reward for seeing ourselves in a lesser light. Does it tear us down a little bit, contributing to a self-fulfilling prophesy? Do we become a club of false humility? Some of us will only say a nice thing about ourselves, if we disclaim it three times first by listing other faults. I swear, the way we talk about ourselves, it’s amazing our dogs like us.

Is it that we think we’re the only ones who falls short? Is it a poorly kept secret that mistakes happen? We’ve got this backwards. We’re human, we screw up. It’s our nature. Normal. Ordinary. No reason to constantly point out the obvious. It’s dull conversation.

Being an affirmative trainer, it’s our job to praise horses. Obviously, that extends to the human with the horse. Praise builds confidence and isn’t that the thing we most want to give horses? And secretly crave ourselves? What would it mean to say it out loud? “I’m getting good with horses.” Would a moment of pride in a job of training well done spoil us? Could we show the horse who’s boss by standing tall with squinty eyes from a big-toothed smile? Can we let confidence fit like breeches, like our favorite jeans?

It’s time to turn “good manners” humility into self-confidence we can honestly depend on. A confidence that can lift our horses in a way humility leaves them hanging. Here are three tips for those who fear they will collapse into false pride:

Stay grateful for your wild luck of being with horses, thankful for the help you’ve had along the way. Let every “Yes!” affirm your gratitude for standing next to a horse.Having a good day is worth celebrating. Let a good day lift you, knowing there will be enough challenging days ahead. Horses are never a static quantity. To be with horses is to ride a wave of constant change. Congratulations. Nice job of staying on!Accept praise graciously and authentically. Remind yourself to simply say “Thanks, it felt good to get that right.” Being humble doesn’t mean under-valuing yourself.For all the cowboys in western movies who flap their arms like chickens and jerk that horse’s head sideways with a shank-bit, while stabbing spur rowels into tense flanks, egads, would you give yourself some credit? I’m not saying they’ll start making movies of women standing next to horses and breathing. Affirmative training, working peacefully with horses, will never be as flashy as whip-cracking domination, but the world for horses will only change when we stand and bear witness to our skill and value.

We can trust horses to let us know if we manage to become arrogant asshats, have no fear. And we will always be learning, but in gratitude to all the horses that came before, let’s brag about ourselves, too. Be proud, we are their legacy. Let’s claim the credit we deserve and see what happens next.

…

We’ve initiated a Brag Club over at The Barn School. Who knew it would be so fun?

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Affirmative Training: A Cowboy Walks Into a Bar… appeared first on Anna Blake.

April 23, 2021

Horses and the Pain We Can’t Stop.

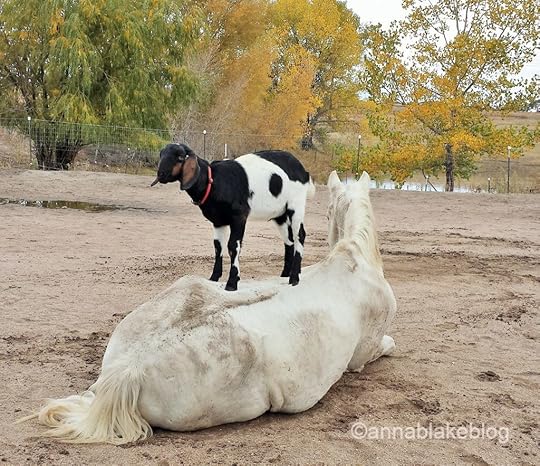

The Grandfather Horse: Dirt Bath Interrupted.

The Grandfather Horse: Dirt Bath Interrupted.We’ve all done it. We look at that horse and just know he’s in pain. We watch his walk until the foot with the white stocking lands badly, crippled by its color. In the saddle, we close our eyes and wonder if he’s off. We scrutinize the horse’s calming signals until he freezes, stalked by an upright coyote. We’ve all made the vet call, only to have the symptoms disappear when the vet arrives. The feeling that something isn’t right stays. Great, no diagnosis for the horse but we think we have a mental illness. It would be funny if it weren’t all too true.

Rule number one is always the horse’s welfare. Is your horse sound? You’ve heard it so often that it loses meaning but stay vigilant. Most horses we think have “training issues” are just telling us they are in pain. At the same time, horses work hard to hide weakness. Prey animals don’t lie but they aren’t forthcoming. It’s just smart to put up a good front. Especially if a vet/predator who smells like other horses, blood, and even stranger things, drives up in a truck. Any prey animal with one wit of sense will go stoic. “Nope, I’m fine. It’s the donkey.”

The absolute best of us spends months thinking something is wrong with our horses, being told by a vet that there is no problem, nothing to worry about, but we don’t believe them. So, we google endlessly, educate ourselves in ways we couldn’t before. We continue to observe and trust our gut feelings, get a second or third opinion, only to find out eventually that we were right, our worst fears are confirmed, and somehow then have less trust in vets.

Please don’t blame vets! Horses do not speak English as they try to hide symptoms. Horses are lousy patients. Sometimes it seems to us that human medical care has progressed so far, that vet science must be right there, too. It’s just not true, but veterinary science is evolving constantly and there are good scholarly articles on recognizing pain. I recommend the Equine Pain Ethogram. It’s important information to have on hand. I should also warn you though, you’ll notice behaviors your horse is exhibiting now. You’re looking for a change from consistent normal behavior, not a one-off. You’ll need careful perception. Like usual.

Horses never fake pain. Scientists agree that horses don’t have the frontal lobe capability to plan deceit or disrespect. They don’t concoct diabolical plans to escape work, but they do have a good memory. This opens the possibility of a horse showing pain symptoms from expectation or memory of a similar situation. Even in something as ordinary as tacking up, a recent study revealed only 35% of the saddles fit properly and nearly 70% of the horses showed some lameness. More troubling, the owners were not aware there was a problem before it was pointed out. Conformation and age are factors with pain. Most horses have arthritis by fifteen, with the initial beginnings between four and six years old, true even if the horse is lightly ridden. Age happens. Then, even if the pain is resolved, it’ll take a period of time for a horse’s pain behaviors to go away. Can we ever be certain?

Some pain is diagnosable and some isn’t. Some pain eases with movement and some worsens. And just like humans, some pain is inevitable.

Some will say we shouldn’t ride horses, as if that was the miracle cure for congenital anomalies, poor hoof condition, or gastric issues. As if feral horses never have injuries or pain or age-related conditions. It’s always easier to look away than deal with a mess of contradictions and help horses; easier to quit than consider the benefits of riding for a horse.

Does the nebulous nature of pain, the circling-around anxiety of not knowing, topped by the fear of causing your horse even more pain, paralyze you? That seems like a fair response. It’s enough to make you spooky and tense, to make you chew your lip and squint your eyes.

As much as we want a clean answer, we can only live in the question. If training causes pain, then can a different sort of training help alleviate it? Horses benefit by moving and staying engaged so we do the same, attending to details, constantly improving all we can. Most importantly, take the horse’s calming signals seriously. Never write off abnormal behavior as cute or silly. Stay curious, not complacent, and uncomfortably willing to see pain when it’s small. Trust our horse’s calming signals over our feelings.

We can train kindly, exploring the horse’s anxiety with finesse, allowing the horse a voice. The true relationship begins when we ask clarifying questions that build confidence and lessen anxiety. Horses will test our commitment and sometimes we’ll have doubts. We’ll make mistakes and we’ll try again. Intuition will improve.

If a horse won’t pick up a hoof one day, we’ll ask him to shift his weight and reward him for the effort, knowing something hurts. If a horse is reluctant to move forward, we know it isn’t natural, so we look for soreness, give the horse time off, consider supplements. If a horse is fussy in the bridle, we take his word that our hands need some help and get some lessons. We listen to what we don’t want to hear, knowing that the horse who pins their ears does it for a reason. Then we stay in the conversation, honoring the horse’s nature. Knowing that life will take its toll, but we’ll meet the challenge. For all the magic and fantasy that horses give us, there will be a morning after. Eventually, pain may win but we will have flown together. The magic isn’t in riding but in gaining language and understanding with another species, so unlike ourselves.

Finally, that photo above. The horse is certainly in pain. He’s over 30. He’s lost his topline, his front legs are shot, his hips decidedly bovine. During his life, he spent four and a half years on stall rest from injury. He was not a particularly athletic horse and he had a slow learner in the saddle, but we did our best, never gave up on each other, and shared a life of pain and brilliance. At this age, it was a struggle for him to stand up even without the pointy-hooved pain in his backside. But still, that’s no reason to not enjoy a cool dirt bath and the fall colors.

The real problem is there’s no cure for the pain of loving horses, but to live in the moment and make peace with the rest.

…

New classes at The Barn School start soon, including Calming Signals, reading signs of pain and anxiety in horses.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Horses and the Pain We Can’t Stop. appeared first on Anna Blake.

April 16, 2021

Saying Yes to a Horse When You Mean No

Sometimes something someone says sticks with you because it’s brilliant. Sometimes it sticks because it’s plain wrong. I was working for a horse rescue a few years ago and a bodyworker came to visit the horses. The bodyworker did noticeably light and sensitive work on banged-up sway back elders and the herd melted in acknowledgment. Shy horses came near. Calming signals were shared and the herd grew silent in that eloquent way that humans never quite manage.

In moments like this, horses show us their vulnerability. Whoever started that story about herd dominance being the truth about horses has never spent much time in the pen. It’s always been about feeling safe even with their instinct to constantly be on guard for danger. It’s in quiet peace when trust feels nearly palpable. Their calming signal so plain, “I’m no threat to you. You don’t have to be so aggressive.” We moved from horse to horse in the pasture, breathing deep into our bellies just because the horses were. It wasn’t a special moment, it was ordinary. Just the way horses are if they are safe from predators. When did this get mistaken for boring?

Back in the parking area, the bodyworker asked if the rescue needed any training done. Careful to add that the training was different because you had to be a strong leader and discipline the horse to be obedient. I was sure I’d misheard, but the bodyworker/horse trainer chatted on about dominating horses with a smile as sweet as spring grass.

I remember this Dr. Jekyll-Mr. Hyde horsemanship disorder because this sort of inconsistency is crazy-making for horses. One moment standing close and whispering, the next barking out ask-tell-make orders. Could anything be less trustworthy?

The bodyworker was a two-for-one deal, but most of us were told to be the boss when we started with horses. The plan was to climb on, and when your horse did something wrong, correct him. It was our job to evoke a quick response from a horse. Act tough, be tough, and get it done. We believed that a horse must be forced to work because volunteering was out of the question. It’s a depressing tradition but it’s all ours. Punishment is the lowest form of expression, even horses have a more evolved language than “NO!”

Lots of us still feel guilty for things we were taught to do before we knew better. Now we’ve sworn off fighting with horses, but that creates a new kind of confusion. We want to do everything at liberty. Or maybe with a whip in a pen and call it liberty because even now we don’t trust the horse. We don’t trust the silence as we stand in the pen anxiously trying to be patient. We wait for the horse to saddle himself, but we’re so busy coyote-watching, that we’re deadly quiet. Any mare will tell you, (persnickety ears), that someone has to start this thing. Meanwhile, the gelding is hesitant because he expects to be corrected, (dark partly frozen eye) knowing he’ll be in trouble soon. It’s the only thing he’s confident of is that people always get scary. He thinks humans (looking away) are unpredictable.

Now being with horses feels as awkward as a junior high school dance. So much anticipation and no rhythm at all. You lose faith and decide just this once, you’ll escalate and get it done. And thus confirm your erratic unpredictable nature to your horse. Or maybe your mind is flooded with techniques/methods/advice that all yell at you at once and you just stop because you don’t want to get it wrong any more than the gelding does.

Looking for the middle path between extremes?

It feels good to stop fighting, both you and your horse release anxiety. Let it be simple. Your priority is the horse’s anxiety level. Punishing a frightened horse is as bad as it feels. Start by being consistent in who you are with your horse. Give him the safety he wants. If you like the clarity of discipline, maintain kindness in yourself.

Yes, you say, but…

Giving your horse a voice doesn’t mean you give yours up. Giving a horse choice builds confidence but that doesn’t mean let him eat a bag of grain. If he stands at the front gate, don’t let him loose in road traffic because he asked. Be his guardian, keep him safe but know that partnership means two voices. Let yours be consistent and affirmative.

Our overall intention is what matters most, a tendency shown in our temperament. In Affirmative Training, the human gets to say what the task is. And the horse gets to say when.

Level ground is needed for trust. In the beginning, it feels like chaos to breathe instead of intimidating. And the horse will take the time needed to begin believing he is safe with his predator and relax his guard (lick and chew) bit by bit. Job one is to lessen the horse’s anxiety the instant we see it. Rather than evoke a response, we relax. He can’t learn if he’s frightened and we need to prove we understand that. This part takes the time it takes but if you give in to past methods, it will take longer.

If we constantly micromanage, horses will constantly resist. So many horses are broken down by constant correction when it isn’t needed, then don’t give a good response when it is needed. We increase the micromanagement. Soon fighting is just the ordinary language. Is our culture one of correction and over-management, or total permissiveness? Or can two negotiate?

Yes, you say, but…

Sure, bad things happen. Injuries or extreme circumstances. I don’t expect horses to volunteer against instinct, but we can maintain a tendency of peace in a chaotic world. He’s reading your calming signals looking for confidence.

If a horse evades a task, it’s never personal. Maybe a horse gets out and you must bring him back. Walk up calmly and say “Good Boy” even if you’re late for work. The priority is always the horse. Give him a scratch. He won’t want to return, so reward him, even before his first step. Keep your focus on his emotional state above the task. It isn’t what we ask, it’s how we ask.

Maybe your horse is getting into something he shouldn’t. You don’t need to rush to scold. Give him an amiable cluck to move along. Use your voice to help him be safe. Hold to the hard-won tendency of kindness even as you assert boundaries. Learning finesse isn’t a quick fix for either of you.

One day your horse will ask (tense poll, jittery hooves) for more steady support when he’s frightened. Reward his vulnerability with a firmer-focused kindness. The elusive middle path, the place of genuine trust, cannot be demanded, only discovered. You’re welcome, (neck stretch, soft eye) says your horse.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes

The post Saying Yes to a Horse When You Mean No appeared first on Anna Blake.

April 9, 2021

Learning to Herd: How Dogs Become Family

I was raised by people who didn’t let dogs in the house. The common opinion was that dogs should live outside or in the barn. On our sheep farm, there was a hard line between us and the animals we depended on for a living. But my mother insisted I spend the day outside with my father and farmers are notoriously lousy babysitters. So, I ran with the dogs and the line was blurred immediately.

In my twenties, my dogs had to have long hair. I cried a lot and multi-tasked them as mops. We left the house at 10 pm and wandered down suburban streets peering in windows from the sidewalk. We saw furniture, men in tv light, and women in the kitchen. Cats peered back from windowsills. I was slow to find a real home, but the dogs gave me a place to be after work, they walked me until I was calm, they gave me a place to sleep at night. It isn’t that I didn’t have relationships. It’s just that when they broke up, I got another dog.

Over the next two decades, I brought generations of dogs to work with me in my art studio/gallery. Many wore black, some had ears like French hats, and they affected an artistically skeptical gaze. Aloof, oblivious of children, and cautious with strangers, the dogs were too cool to wag. Any illusion of sophistication I have, I got from them. I learned to have a dog in my professional headshots because alone, I’d tense my neck and hide between my shoulders in a way that made my head look the size of an apple. When people asked if the dogs were in the gallery for protection, I tensed my lips into a straight line over my teeth nodding, certain I was hiding my secret.

Once I moved to the farm, the dogs stretched out. They napped by the arena when I worked horses and trotted along to the barn for chores, always tripping on my heels and pulling my socks down. They took the herding job seriously, running laps around my pens to keep track of the horses and llamas inside. When I trained off property, they came along to guard the truck. At night we shared a beer and howled at the coyotes from the comfort of the porch. Horses may be my fondest passion, but I slept in a dog pile.

All dog stories end the same way, but I’ll never blame a dog for having a shorter life than mine. I did my best to help as long as I could and then let them go before the worst. Sure, I mourn them, but wouldn’t it dishonor a dog if we gave up herding or playing ball or sleeping in a pile? Wouldn’t they prefer their beds are used and their bowls filled? Of course, I cry big snotty tears and hack phlegm into a wadded-up bandana, but since I will miss that good dog forever anyway, I get another dog.

A different generation of dogs naps under my desk tonight as I write. Literary dogs have a barely audible snore, tend to be a bit soft in the waist, and would have you know that writers are as clever as clothes on hangers.

When the pandemic canceled my travel schedule, I started an online Barn School and the dogs took up a second job timekeeping for Zoom meetings. Preacher Man is a master of wiggling into my lap as I start to wrap up, staying just off-camera, but digging toenails in as he spins to settle. He’s a bit too long to be a lapdog, but he’s no quitter. On camera, I look like I have gas, a sporadic speech impediment leaving me unable to finish a sentence, like my breasts have suddenly come live inside my shirt.

I’ve been self-employed for over forty-five years now, and I have never worked alone. I’ve never even gone to the bathroom alone.

When my parents were alive, they frowned at my rag-tag hairy family, saying it wasn’t how I was raised. I remember differently. Dogs became family not just because they were the historical choice. They seemed remarkably good at it. Dogs have had my back, in one way or another, all this distance and not once was I lost.

There is always an old dog in the pack. Right now, it’s Finn. He’s the Dude Rancher’s dog, my step-dog. I swear, draw any line you want, and a dog just won’t care. Finn is one of those dogs who hated to play ball but didn’t want to disappoint. He’d saunter out to the ball and pick it up. Then he got flustered, looking both ways first, he’d skulk away. If you chased him down and threw the ball again, he’d follow it nervously, feeling obligated to pick it up, but then look embarrassed. Sports-dread. He wasn’t stupid, it’s just his heart was never in it. Now his hind legs don’t always move properly, so I stand behind and to one side. We both take old-dog-sized steps. I never nip at his heels and it’s useless to talk to a deaf dog, so I wait. The slower Finn goes, the more time I take. It’s about the only way a human can improve for a dog.

Car rides scare Finn now. Loud voices make him cringe. He thinks the backyard might be haunted. Sometimes when I’m sitting on the toilet, he rests his gray muzzle on my knee and lets me know he’s fine. That it’s okay being an old dog who likes a head scratch. No regrets and no more plans for the future than he ever had. He’s fine, as near perfect as a dog can be.

For Finn:

A deliberate old dog with gray dreadlocks and a

stiff stride paces the backyard. A badly constructed

mixed-breed with a heavy body on spindly legs,

but too restless to nap. He has worn a path along

the fence line but he remains a bit bewildered, not

trusting his clouded eyes, his nose intent on the air.

Is there something in the distance just beyond? Give

him extra at dinner to hold his weight, an egg on top.

Call his name. He appreciates the reminder with

a wag but doesn’t come. Old dogs do as they like.

It’s cooler after dark, but he can’t find his way back

inside, so he stands and barks in a flat tone, one boof

after another, plaintive and blunt. Here. Here. So,

I go there, guide him up one step and in the door.

He takes a drink, water trailing from his whiskers

across the linoleum, then again, the plastic flap-flap

of the dog door. Soon he calls, more impatient now.

Here! Here! Answer the bark, rescue him. Hold the

door wide, wait till he recognizes me in the threshold

light. Give him the time needed to remember his home.

He pauses to listen, his ears long deaf. Still not certain,

he rocks onto one leg to pick up the other, and just so

tired, he paddles past me, his tail following reluctantly.

Not a wag really. It’s more like a slow wave goodbye.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Learning to Herd: How Dogs Become Family appeared first on Anna Blake.

April 2, 2021

How Humans are Different from Horses

In the beginning, a filly is born. In the hospital, a baby girl human is born. The filly stands almost immediately. The girl breathes and cries. In less than one week, the filly gambols laps around her mother on long legs at breakneck speed. She is champing, a calming signal sending a clear message, and begins demonstrating the Flehmen response, the first behavior that will eventually be associated with sexual behavior. At the same age, the girl comes home from the hospital and can barely see past the end of her nose.

The girl will take another month or so to lift her head, and start walking, finally, at around 18 months. By then, fillies have gained over 2/3’s of their full body weight.

Around two years of age, the girl will enter a normal developmental phase experienced by young children that are often marked by tantrums, defiant behavior, and lots of frustration called the “terrible twos.” Finally, some commonality. Two-year-old fillies often show similar behaviors, but they are adolescents capable of breeding. They have raging hormones as well as immature minds. Two is a good age for those around girls or fillies to breathe, take a deep seat, and a faraway look. Wait it out.

Horses mature slower than we’d like and girls even more so. I wonder if some of us ever do where horses are concerned. We want what we want.

By 11, girls might be interested in STEM (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and are feeling as awkward as possible. Many are card-carrying tomboys who live in barns and like biology. Mares that age have found their mature strength, all bones and joints are fully developed, and they are glorious. Then around 13, girls hit adolescence —or adolescence hits them, and some of us revisit our terrible twos.

The productive potential of a mare typically begins to decline by about 15 years of age, along with her prime riding years. At 15 some girls worry they’ll get pregnant walking past the boy’s gym and others swear off boys forever. At 15, most girls have given up STEM courses, because of peer pressure, or lack of role models or family support. For most, it’s a time of insecurity and even if we are beautiful and smart and capable, it’s a time when the pressure to follow societal norms is high, whether you try to fit in or not. We look to less well-paid careers, are encouraged to give up crazy dreams, and feel our shortcomings.

“We have to rethink the way we raise our girls,” Reshma Saujani, founder and CEO of Girls Who Code says. “Boys are pushed to take risks; girls are not. In fact, they feel like they have to be perfect at everything they do; they see getting a ‘B’ in math class as bad. We have to teach girls to be imperfect.” Mares do seem to help us with that, one way or another.

Women who have children then spend around 18 years rearing each child, mares usually wean their foals at about a year, and the young transition to herd-mates. Most people don’t reach full brain maturity until the age of 25, with the last area to finish, the frontal cortex. Hence, teenage behaviors and “poor” decisions. Horses have a small frontal cortex that does not serve the same function as a human’s or develop with age. Horses have a lightning response time, and we overthink. Horses read the emotions and anxiety in our body language but that doesn’t mean they share the same emotions.

Mares cycle less frequently after 18, as they become seniors, but are still capable of breeding into their 20s. Women go through menopause, the ceasing of menstruation around 50, and for some of us, exhibit behaviors only slightly more mature than the terrible twos. Mares continue to have some level of hormones throughout their lives, more like stallions than geldings.

At some point, most women stop asking permission and curtseying to the wishes of society. Mares say about time, not that we ever did.

Mares are prey animals, flight being their common response to danger. Every day is life or death, domestication doesn’t change that. Mares keep their eyes to the horizon, wary of danger while managing cooperation in the herd. Their primary concern is safety. They are considered motor sensory animals; they run before they think.

Women are considered predatory animals. It’s an oversimplification to say we eat meat. Predators that exert top-down control on organisms in their community are called keystone species, one that has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance, a concept introduced in 1969 by the zoologist Robert T. Paine. Examples are bears, wolves, prairie dogs, and humans.

As with many predators, women are also prey to other predators, including those in our own species. Humans feel fear and an instinct to survive. We have a similar autonomic nervous system to horses.

The lives of horses and humans have been intertwined for centuries, we have depended on horses to carry us to where we are today, and we owe them a debt. At the same time, humans need horses less now than ever. It’s awkward.

We set about training horses, but we’ve been fed a false narrative, a story told by predator-humans who saw some small part of themselves in horses, and believe domination is their natural right. They call it herd dynamics, but the behavior of stallions does not define the herd any more than the behavior of men solely defines humanity.

But train on, we do. Forgive the horrible generalization, while men dominate, and women coerce by more passive-aggressive means. The goal is the same, we manipulate equine behavior and say we listen. Humans listen to horses, (another harsh generalization,) like men listen to women. We lack understanding of their unique nature and experience. We want what we want.

At the same time, horses are not capable of understanding human logic. Bluntly, horses don’t understand how humans think. Their brain doesn’t have that function. At the same time, horses are highly intelligent but not in ways that humans, seeing through our own pinhole of perspective, can quantify or understand.

Dominance-based training methods have caused anxiety and dysfunction for horses, and some women, too. What would happen if humans stopped treating horses like a lesser species? Rather than training horses things they already know, we studied their ability to cooperate with each other. We could mirror them, learning their language of calming signals, and then quietly negotiate desired behaviors. When women of a certain age value their experience of being at times both predator and prey as a special perspective in training horses and acknowledge that our maturity-earned common sense and patience, we will understand our worth to horses and ourselves.

Horses teach us so much about who we are and yet they remain a mystery to us. Horses are always horses. Perhaps instead of looking at our perceived similarities, we would do better to understand our profound differences.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post How Humans are Different from Horses appeared first on Anna Blake.

March 26, 2021

Calming Signals: How Do You Listen To a Horse?

What is your first memory of listening to a horse? Not standing next to a horse and being certain he loved you. Not daydreaming about galloping him on the beach or burying your tear-drenched face in his mane and hiding. None of these things are listening. They are moments we might feel a connection because we want that more badly than anything. If wishful thinking worked, we would have all married princes in middle school. Listening to horses is something different.

The first thing I remember hearing from a horse was fear. I was maybe six years old and riding my pony bareback. I felt her body go tense. Her neck got stiff and her feet danced but I couldn’t steer her. She was scared all the time and I’d fallen off a few times, so I was tense, too, not that it mattered who got scared first. Even when I couldn’t avoid it, I’m not sure I listened. I wanted her to listen to me and just stop it. I probably pulled the reins thinking it would stop her. Ponies don’t really respond that way, but it took me longer to figure that out. Crisis listening is active denial. It’s when your horse tells you something you just don’t want to hear, and it isn’t limited to childhood.

I’ve lost count of the number of riders who are certain they have a training issue when in truth their horses are literally in pain. It can be a sore back or lameness, or the pain our hands cause in their mouth. The upside of listening to pain is that we can help then, but sometimes we’re convinced that the horse is trying to trick us, or that the horse is spoiled and trying to get out of work. It’s biased listening, hearing only what we want to hear. We misinterpret his behavior into some stereotype and then look for a training tip to fix the behavior. We can’t avoid hearing the horse’s discomfort, so begrudgingly, we’re listening but not in a way that helps the horse. We become critical listeners; we listen to evaluate and judge the horse, forming an opinion about him so we can correct him.

A bunch of us take a left turn about now. We just don’t want to fight with a thousand-pound flight animal. It’s a glimmer of common sense at last. We end up with a rescue horse, or a horse that we didn’t know was a rescue horse. There is no shortage of horses with anxiety issues. It’s our intention to be a sympathetic listener but we might become overly sentimental, telling his history to ourselves, feeling good for saving him. Getting a horse to a safe place is a good thing, a true gift. Maybe feeling pity is a kind of listening, but how does feeling sorry for a horse feel to the horse? Is it a nebulous coyote-stalking kind of anxiety when a predator stares at him quietly?

So far, for all our attention and concern, we’re just having conversations with ourselves about horse behavior and a horse’s fear will not be quelled by a human telling him to stop it. Fear is an essential part of what it means to be a flight animal; that part of a horse that we like least is fundamental. The best we can do for a horse is to build his confidence, so fewer things are frightening. Any horse will tell you that discipline isn’t an antidote to fear. If we listen.

Step one in horse training has to be accepting that horses have emotions. We’re good with happy emotions but when a darker emotion shows itself, we don’t like it. It would be an evolved moment if we heard them without a negative response in our bodies. Accepting a negative message doesn’t mean we are rewarding it. Sometimes just being heard lowers the temperature, especially to a horse who’s been punished for his natural instinct.

Active listening might be something we learned in couples therapy or leadership training for work. Active listening is positive listening that keeps you engaged with your conversation partner by being attentive, paraphrasing and reflecting back on what is said, and withholding judgment and advice. We let the conversation unfold rather than shutting things down with a blunt solution. Is it too obvious to say it doesn’t come naturally to all of us?

Active listening involves using all our senses: we keep eye contact focused on the other person. We might lean forward a little or nod, but we aim to sit still and let the other person finish what they are saying without interruption. We breathe, offering interested silence to give the person time to respond. Most of us find listening so purposefully exhausting at first.

Wait! Horses use all their senses to communicate; they speak in a body voice, whether we try to shut it down or strive to understand. Their calming signals are a literal language of active listening to the world around them, expressing their feelings, and processing it all. Calming signals are humans’ fundamental language, too, before we overthink it. When we exhale, slow down, and allow a horse time to process the moment without interruption, we are acknowledging the horse’s intelligence as well as our own. We can’t control a horse’s behavior, but we can create an environment where they can become more confident. Calming signals be our shared language, resonating deeper than words ever can.

Maybe now we’re finally capable of true empathetic listening, letting our feelings rest, and seeing things from the horse’s standpoint. There is a quality of selflessness required, a state rare in humans. Empathy takes practice and truly accepting the horse’s calming signals in the moment is huge but what comes next? Long-term anxiety isn’t the answer any more than adversity. Perhaps we can begin an affirmative conversation with radical listening, believing not just that the horse has a right to his feelings, but surrendering our side for his. Begin with alignment on a starting point: the horse is right.

…

March marks the beginning of my twelfth year of blogging; I’m a horse trainer who has sat down every Thursday night for the last eleven years to write a message about listening to horses. I owe a debt a gray ghost of a horse on my shoulder. He says another twenty years or so and I might get it right.

I’m grateful to all the horses I’ve had the privilege to listen to, and especially grateful to those of you who have read along over the years. Thank you for your precious time.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Calming Signals: How Do You Listen To a Horse? appeared first on Anna Blake.

March 19, 2021

Horse Intelligence: What Are We Missing?

I love science like hungry people love over-cooked greenish-gray Brussel sprouts. And that’s the kind of sentence you never come upon while reading scientific research.

I have better luck understanding these behavioral studies if I read them aloud. The words all seem to trip over each other’s feet; science jargon is a language of big words and self-important run-on sentences. In their defense, scientists probably wouldn’t be wild about my oversimplification of the same topic. This week, I’ve been studying social learning theory. I have a passion for evolving my understanding of horses because we could always do a better job of training them. Because after a life with horses, I honestly believe we are close to a breakthrough in understanding this creature who is like no other. Not like a cow or a dog or a cat. Horses are in a category of their own.

Science affirms the mistake of fear-based training, so I love science. At the same time, we have precious little research on brain dysfunction in horses. Is it possible all horses are born physically perfect, in a way that humans are not? Science also has a rich history that includes steel-rod lobotomies, leeches, and electrical impotence cures. We humans are works in progress and that might be the best thing about science. You gotta love all the question-asking.

At some point in school, I learned that Edison invented electricity, but he didn’t. Electricity was always there, he invented the light bulb. It’s one of those small semantic details that make all the difference. What else haven’t we discovered? Are we missing something hard to quantify about horses that will be obvious in hindsight?

At the same time, is there an animal we have more romantic (and less scientific) notions about than horses? We see them as manifestations of freedom but keep them in stalls. We value their strength but work them past soundness. We think they’re magically psychic because they understand some of our emotions. Yet we don’t listen to their emotions as well as we should. We think horses want domination or that horses are hapless creatures who need our micro-managing care, but most of us are between those extremes, trying to find a middle place of understanding. We are looking for something beyond evoking a response. We search for an authentic connection without intimidation or baiting.

Here is my favorite sentence from a recent research paper: “This shows that although horses are quite intelligent, their personalities vary so greatly that we can’t simply use one metric to measure their intelligence. Researchers will continue to modify and conduct this test to really get the answer.”

This wouldn’t be news except for things like the ongoing controversy over gender, race, and economic bias in college entrance exams. Is one group less intelligent, with less potential, or are we asking the wrong questions? Do we ask the right questions in the wrong language? That’s why I savored this sentence, in a study that each horse failed, because it acknowledges the difference between individual horses. It sounds like the researchers could see intelligence but had no way to quantify it. That sounds about right.

Horse owners have something that science doesn’t. Historically, we’ve ridden to battle and traveled great distances. We’ve had their help building homes and planting fields. We put little girls on their backs to be rocked until they climb down, thirty years later, being better for the ride. Our lives have always been intertwined with horses. Even now, we risk life and limb riding, understanding their flight response in visceral ways, and we’re honest to say that horses have stepped up for us, filled in for us, or even saved us. Horses somehow let us know there was something much bigger below the surface. Sometimes we call it heart but it’s a frustratingly flat and trivial word for what our relationship has become. And if we have the opportunity to work with a horse without human language getting in the way, maybe a long trek or a solitary path of training, we learn the depth of meaning in simple words like empathy and trust. Science doesn’t have an explanation for the hook horses have in us but I hope the science evolves. I hope horse people evolve as well.

Longtime horse owners have experience that taints our belief in the studies. If the research requires that horses be taken from their herds for instance, we know the horses are stressed already. The answers will be colored by separation. We have a lifetime of knowledge that boils down to anecdotal evidence and which science considers the equivalent of old wives tales. But is all anecdotal experience false? We observe our horses just as closely, we know how much horses change from day-to-day and evolve over the course of their lives. No one needs to tell us that quantitative information can be fleeting.

When will we learn to stop making up narratives and actually listen to horses? When we still the noise in our heads, when we let the air rest, horses tell us more than science can define. Perhaps we are on the edge of returning to the language we lost with civilization. Perhaps we will discover something that’s been here all along, and we will become fluent in the equine body-voice or calming signals and get our answers straight from the horse’s mouth.

Do we diminish the intelligence of horses by asking the wrong questions or by not being able to understand their answers? Without dissecting or anthropomorphizing, I am looking for a different relationship with a horse. Can we find a way to elevate the conversation rather than assuming that we know who they are? If we dumb horses down, we are the limited ones. We need to ask better questions, as scientists or horse owners, and then find creative responses, just in case there is a dimension of understanding running just parallel to us that horses are waiting for us to find, lurking for all time like electricity.What if horses understand Shakespeare but we’re teaching them Dick and Jane primers?…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Horse Intelligence: What Are We Missing? appeared first on Anna Blake.

March 12, 2021

Life Happens: The Unplanned Dismount

“I owned horses for 20 years until divorce happened,” the reader said, asking me to write about it. “I think they are the only thing that kept me sane and leaving them was the hardest thing I have ever done.”

The reader said it was literally a matter of life or death. I believe her because isn’t that what it would take? Do you raise your voice with brassy bravado to say you would keep your horse no matter what? Well, bless you for the luck of your vantage point. May your life be a straight flat road.

It isn’t always as dramatic as a hostile divorce. An ordinary divorce is challenging enough. Lots of us take a short detour even earlier and we only see how far we’ve wandered in hindsight. We step away from horses to go to college. Maybe we join the military and have a gypsy life, never in one place long enough. Along the way, we fall in love and have a baby thinking it won’t change a thing, and then one or two more brilliant, beautiful children, and a decade has run past. Lots of us live in town and would need to board our horses, which ends up being practically a second mortgage payment. As if that first mortgage payment was easy, but we have a plan for an eventual horse, even as the distance grows.

Some of us are blessed with a career we are passionate about but it requires long hours and a few years to establish ourselves. We take the strength and focus that we learned from horses into our work, maneuvering our way over obstacles, and keeping our eyes on the horizon. We are aware of the personal price we pay, but like a good workhorse, we get the job done because we know the satisfaction that comes with making a difference. There is a price to be paid for birthing any dream.

Sometimes the separation happens later in life when, at a certain age, the impracticality catches up with us. Horses have always had an edge of danger, but people depend on us now. Horses carry the burden of our lost youth but we won’t let go. Then it’s our turn to care for our parents or maybe it’s our own health that needs our attention. Some of us were born loving horses but never even had a chance as a kid and now the dream of a pony is just a small splinter that got under our skin but we never managed to pull it out. Now there is a hard lump of callus, a rock of pain and hope just under the skin, as true as a scar but without the initial injury.

We are no more in control of our lives than we can defy gravity. Maybe the hold horses have on us is that temporary possibility of flight.

Horse-crazy girls all start with the same plan. We know we’ll have horses forever. We’ll never give them up. Then life happens and we take detours, we build lives and we help others. We are indispensable in the world for all the best reasons, but we might get bucked off horse ownership along the way, no matter how hard we fight it. What then?

It takes a while to figure out that pain is equal to how much we cared, and then we’re grateful in a bittersweet way for the gaping hole in our hearts that lets pain wash through us. We’re tougher than most, so when the wound starts to heal, we tear the scab off. We look at old photos. We slow the car while passing horse pastures, and if it’s spring and foals are landing, we just pull off the road entirely and let the pain and love wash over in equal measure. We can’t do this alone, so we take in a couple of elderly stinky rescue dogs and a one-eyed cat who’s a mouser. They sleep next to us on the couch while we watch the same horse movies we’ve watched a hundred times, bleary-eyed and hungover for days after. Sometimes late at night, slouched in a hoodie with a glass of whiskey, we ride the internet, looking at videos of competitions and horses for sale. There is sweetness that horses exist in this world, whether we own them or not.

We tell ourselves it’s better to have loved and lost, loved and never had a horse at all, than to give up that sharp rock of a dream. After all, the dream of a ride and a memory of one reside in the same place, remarkably close at hand, and on the hard days, you can close your eyes and feel yourself be carried through. Some obstacles are jumped and some, we must outrun. We are born predators but still prey to the experiences of life. We’re only human in the end, but the addiction to a notion of freedom, first borrowed from horses, has become our own. We can stop being victims of what we lack and rise to gallop at the sun. Our gaits might be arthritic or ungainly, with scars that are visible and scars that still cut deep inside, but we are also invincible.

Some of us find a way to circle back and find horses at another time in our lives and some don’t. Either way, there comes a time we understand that not having a horse doesn’t stop us from being a horseperson at all, a reality is as freeing as a gravity-defying gallop on the beach.

There is a call to arms, disguised as an adage, that when you get bucked off a horse, you climb right back on. It isn’t about punishing a terrified horse or showing some caricature of woeful dominance. It’s about the bigger picture in life; it means we aren’t quitters. We get back up because we’re strong enough to believe in second chances.

…

[The Back in the Saddle, a Comeback Conversation course is starting in a week in our Barn School. It’s for humans getting back to horses, horses coming back from time off or rescue, or anyone looking to start over in an affirmative way.]

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Life Happens: The Unplanned Dismount appeared first on Anna Blake.

March 5, 2021

Whoa. A Hands-Free Halt.

She’s an 18hh Thoroughbred-Shire cross. She’s 30 years old and her name is Thyme. I’ll give you a minute to smile.

Thyme lives in England but managed to get her rider to email me with a question. “Did you ever write a post on the halt?” he asks. “She will stop in the school, but it’s a different story on the trail. I don’t think she wishes to listen to me.”

Thyme may be half-deaf but it doesn’t mean she wouldn’t like a quieter cue. I ask the usual questions, and yes, he’s trying to break the habit of using his reins to stop, not that it’s really working.

“I am loaning her from a local yard. They thought she was going to have to be put down at the end of last winter as she looked so bad as she is a poor doer. She’s too old to be useful as a proper trail riding horse but suits me fine. She put on a lot of weight over the summer and is still looking pretty good now. The right horse definitely found me, she is a great teacher but sometimes needs some outside help for her slower students,” the rider adds.

Far be it from me to disagree, Old Girl, but he seems smarter than most.

My guess is that Thyme has aged out on having her face pulled. And by that, I mean even the thought. I know you aren’t pulling hard because she’d have you off, she wouldn’t suffer idiots. My guess is that you do a sort of kind-hearted slow-motion lean on the rein, just an ounce of pressure at a time, and she returns the same ounce back, as she strides on. She does it instinctively to protect her mouth. If the rein slacks and tightens, it’ll hurt more. She’d tell you horses don’t give to pressure. Maybe she was manipulated to concede in the past, but her arthritic neck… Aged out on that, without regret.

See it from Thyme’s side. Why would a human ask feet to stop moving by pulling on a horse’s mouth? The two body parts aren’t related. I agree with her, reins just confuse the question. You say stop and she says don’t touch my face. (She softens an indignant eye.)

I’ll give you my best system for halting without hands, but I warn you, it won’t work for a while, because you have some things to prove to this mare.

Start by making a neck ring. You’ll need about 7 feet of rope, 1/2 inch or so thick. Measure it so if you were in the saddle and there was an imaginary oblong tissue box on her withers, you could hold it up at either end of the box and in front of your saddle. Tie a square knot. Start in the school. As you ride, you’ll feel the rope contact where her chest and neck meet. Your hands will hold the reins long, but both of you feel the neck ring before the bit. Now her face is out of the conversation, not that she believes it. Please bend elbows, and hold your own hands slightly up, rather than resting the heel of your hand on the reins. (She nods almost imperceptibly.)

How do we send a cue to their feet? First, take a walk. She needs a good long stride to warm her cranky joints. No contact with the reins, just the neck ring, and care more about her stride than steering. Feel your sit bones in the saddle. One goes up and then the other. Using just your sit bones ask for a longer stride. She may or may not oblige, but act like you don’t care. Then back to the normal walk. Then again with just your seat, ask for a smaller step or two and back to her normal walk. By now, you’re more relaxed and you can feel a difference in her stride, longer and shorter. Exhale to congratulate her, watch her neck stretch just a fraction. March on freely forward. Don’t hurry her, but keep energy in your sit bones, asking for stride changes with breaks in between to thank her. (She gives me a sideways ear.)

There you are, working on your halt. You are moving together, communicating with your seat in rhythm with her stride, and influencing the length of stride. The rider’s seat cues the horse’s hind. It’s logical that if sit bones moving means walk on, then still sit bones would be a halt. (She ignores me, as this is just common sense.)

In preparing to halt, I count three strides with my sit bones, and on three, I melt to stillness in the saddle. She won’t stop yet, but she might slow down. Tell her she’s a good girl.

Go again, knowing that forward movement is needed for any transition, ask with your seat for a long walk, count and melt on three. This time exhale long and slow. Some people say whoa, that word is nothing but an exhale. Thyme might be aged out on chatter, so I advise just an exhale. She still didn’t stop, but she has heard the exhale twice, so now she’s listening. Soon, the exhale will be the only cue to halt but she doesn’t trust it yet.

On the next try, ask for long strides, count to three and melt, as you exhale audibly, and lift (don’t pull back) the neck ring. Maybe lift and hold it tight to her chest, or maybe lift and release a few times. See what she says. She probably still won’t stop but now she’s thinking more about her shoulders and less about her face. Particularly good girl.

You’re waiting for a marginal stop, maybe in five or eight strides. You’ll cheer and vault off her back quickly. Then stand away from her head, breathe, and give her a minute. Horses learn in hindsight, let her figure out what just happened. That you had a clear idea without interfering with her mouth. She won’t be perfect the next day because she isn’t about to spoil you now. You’re changing the conversation and she’ll take the time she needs. I could give you a fancy half-halt lecture, but she’d think we were showing off. Just stick with the neck ring, don’t drill it, and praise her endlessly. Eventually, you exhale, she halts. She’ll stop when you’ve proven to her that you can ask with no hands because it was never really about the halt at all. (She gives me a moist snort from her big old lips.)

Dear Rider, I don’t know the instance she doesn’t stop. It might be she wants to go back to the barn or charge up a hill. It could be a hundred anxiety-fueled reasons, but when one of you softens, the other will follow. I hope you’ll stick with the neck ring, and as long as you are both safe, let her take you for a walk. She knows everything, and you’re a good student. I kinda hope she never stops.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Whoa. A Hands-Free Halt. appeared first on Anna Blake.