Anna Blake's Blog, page 17

June 24, 2022

The Failure of Good Intentions

There was a time that I thought if I saw my horse curled to one side, itching his flank, I should run over and scratch the spot for him. That if I could acknowledge his itch and resolve it, in time I could teach him to show me where he had pain. My work with horses took a turn for the better when I got over that.

Let’s start at the beginning. You know us. We are adults who love horses and also have checking accounts. We have huge hearts that we open wide for animals. Our hands are strong for work but also soft for doctoring wounds. When we were little, our first sentence was, “I’ll do it myself.” And much to the chagrin of family members, we are very independent thinkers. You know us. More than likely, you are one of us.

We like it when things go well, and so, we are the best judges of how everyone should behave. We like our cats to curl up and sleep together. We like our dogs to hold their ears up and not bark or shed all over the bed. We like our horses to be calm with perfect manes and never ever spook. We despise dirt or mud. We know our animals love us and in return, we only mean to help. We are walking, talking orbs of good intention.

Old cowboys would call us “counterfeit.” Just a little too good to be true.

We only want to get it right. Then a horse has a spook. It’s a full-body mini-explosion, every muscle tenses and releases a second later. If we don’t pull the reins or lead rope, it’s over quickly but we all act like someone farted in church. Like it’s a crime to be a horse. We all nervously look for the scary thing. We debate that with each other. Then we relate every scary thing that has ever happened to us because we like to raise the dead. While we’re at it, we complain about bad horse professionals we know of, vets or farriers or trainers. We bore our horses beyond reason talking to other humans. Horses ponder spooking to get our attention but fear isn’t a game to them, so they don’t.

We fiddle with our legs in the saddle, threatening their sides when we aren’t asking anything. We start steering before they even take a step as if horses were going to run into the rail if we don’t pull a rein and soon our horses begin to toss their heads. We punish them for our fear of going too fast and ask them to go too slow to balance themselves. Now they don’t want to go forward at all because they’ve lost the desire to try. Does the horse have a bad attitude or do we telegraph our uncertainty, as well as every other irrelevant thought that crosses our minds? Wouldn’t a blue velvet pad be nice?

We try so hard to be kind and light and flawless, that we give confusing cues. Just as the horse is about to do what we ask, we switch to another cue. Then we contradict that one and go back to the first cue if the horse hesitates and thinks one second too long. Soon the horse pulls inside just for the quiet. Even a gelding will tell you that being too mushy and unfocused is as cruel as harsh methods and angry hands.

Can we at least tell the difference between what we do for them and what we do for ourselves? Any self-respecting mare would tell you it would be just fine with her if you never touched her forelock again.

When we micromanage we teach learned helplessness. It’s the message we send when we feel we have to be perfect. We hold a constant low-level anxiety that says no matter what we do, it isn’t good enough. It doesn’t matter if we feel that way about ourselves, our animals all take it to their hearts too. Because the harder we work to fix things the more we imply something is wrong. Learned helplessness, the idea that we will never succeed or be confident, is the foundation of depression. Are there horse so shut down that they seems to have lost the will to live?

Take a break. It isn’t our job to make things perfect. Cats will always hook a claw in something, dogs need to roll in stinky things, and horses will never be bombproof. And by the way, what if the release of a spook feels as good as a sneeze?

Remember who we are? We have the strength to be vulnerable but not fear being foolish. And courageous enough to hold to honorable standards that we have to strive to reach. And creative enough to feel the joy in having low expectations, knowing we get to praise ourselves and our horses more often.

For all the cheap talk about humans and horses bonding in some mystical way, could we just stay present, focus on one thing at a time, and have a civilized conversation? Yes, it takes confidence to go slow. It takes trust to give up the fantasy of control and let horses be horses. We are all working without a net and trying to like it.

Pause. Consider the moment we recognize our horse has a problem. Perhaps the horse is standing on a rope or we think he needs to rebalance at the mounting block. Knowing that our first instinct is to lean in to help, just don’t. Let the horse figure it out and win his own confidence.

The horse’s reaction time is seven times quicker than ours. That’s how we get in trouble but we are too fatalistic. The flip side is that things come back together seven times quicker. Be still and let the horse think without the interruption of another cue or an unintentional body movement.

Find the patience to let time tick away. The horse doesn’t need help, listen to his calming signals and settle. Let him be curious, and he’ll figure it out. If you were the first to say, “I’ll do it myself,” now let him. Take another breath and watch it happen.

Are we overthinking learned helplessness? Smile because that’s funny. Have I just killed a bit of our romance with fixing horses? I hope so because the thing that comes with letting go is a mature, full-blown relationship between partners with two distinct voices. It starts the day we stop talking down to animals.

I contiue listening and learning. What do I do NOW when my horse has an itchy flank? I trust him to take care of it. When he bends toward the itchy place, his opposite side gets a full body stretch, each rib and vertebrae. Sometimes he balances on three hooves; it’s almost as good as a roll. Why would I deny him that?

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post The Failure of Good Intentions appeared first on Anna Blake.

June 17, 2022

Euthanizing and Herd Anxiety

“I’m wondering if you could address animals and grief in one of your columns. We’ve lost a horse and a dog in the last two months. The horse that was a pasture mate is still occasionally calling for Jake. Lily is really struggling with the loss of Essie Lou. I now see the value of letting an animal see and smell the body of their partner. The depth of Lily’s confusion and sorrow is just heartbreaking.”

First, my condolences to anyone who has suffered the loss of a beloved. I want to talk about this touchy subject, and there is never a good time, so to the friend who sent me this note, I hope this helps in some way. Even as I know it won’t change a thing.

Warning: I’m sharing somewhat rational thoughts about irrational loss.

When I met Essie Lou, she was the Good Dog, adult and polite, confident in her position, and kind beyond reason. Lilly was a wild puppy who had a bit of time-share on the older dog’s brain until she grew into herself. Older dogs can give a pup a good launch in life, but when they die, there is a loss of confidence which might have really been Essie Lou’s all along. Lily has to be the Good Dog now, with big paws to fill. She’s lost a big sister/mentor and a friend. Lost as in the last thing a herding dog should do. And for now, she’s an only dog. We can say Lily is mourning but it might be separation anxiety. Confusion and sadness for her aloneness. Too pragmatic?

Just the previous month, my friends lost Jake, their longtime companion, to colic at 24. He was a perfect horse like they all are. Jake’s pasture mate remembers him, of course, but is it mourning or separation anxiety. Changes in the herd, horses coming or going, always create stress. Horses and dogs don’t like change any more than we do. Is it more than the usual stress of bringing a new horse into the pasture? I’m not saying horses don’t mourn, but does our loss color how we read the others in the herd, if it’s even possible to see through our tears? Is that too cold?

Maybe the problem is we think separation anxiety is merely a training issue.

My friend’s losses were sudden and unexpected. Emergency losses are quick and horrific. Old-age euthanizing comes like a slow train with months of hard questions but in the end, are quick and horrific. And also a bit easier to accept. Is there something to learn that would help us with the sudden deaths?

When my Grandfather Horse was euthanized, I thought we would all die with him. The herd took a short look at his body and went back to lunch. His goat fell asleep by his back, as I sat by his head and had a good think about who was mourning and who wasn’t. My Grandfather Horse had been frail for so long, I’d seen other herd members act like caregivers, feeling stress and giving calming signals of all sorts. In some ways, they shared his pain. Now they seemed almost relieved. Do horses get compassion fatigue? Last year, our senile old dog was euthanized and the other dogs showed so much relief that I felt guilty for waiting too long.

Animals have emotions similar to ours, but without the same brain functions, by definition, they do not experience what we do. For all of our similarities, there are as many differences.

When my younger gelding was four, I bought his dam and brought her home. They recognized each other but had no interest. It wasn’t a tearful homecoming. No one thanked me.

Rather than overwhelming my herd with my own emotions, I try to listen to them. Sometimes there’s a profound relief when a herd member or a pack member is no longer in pain. It’s natural that their pain impacts everybody in the herd but if it grows gradually that we might not admit to seeing it. But when their pain is gone, everyone lightens. Maybe animals, living more in their bodies than in their minds, move through grief in a more functional way. Maybe not thinking about the future gives them a simpler perspective.

Humans juggle these three over-ripe tomatoes: mourning and relief and guilt. Then we remember childhood dogs hit by cars and horses sent to slaughter by our fathers. The pain is still there. And none of us is getting younger. We are caregivers, or ex-caregivers to our parents, spouses, and dear friends. We worry about death and have anticipatory grieving. Once we get to a certain age, if someone hasn’t died lately, we know someone will soon. And then we think we hear Old Yeller barking out back. It’s hopeless. We are bottomless pits of mourning, relief, and guilt counterbalanced by this one thing. We also love.

Humans can romanticize death by dressing it up and giving it the imaginary power to take something away, even as we know we will never let go. Mourning is the period of time we figure that out.

I don’t want to confuse an animal’s mourning for my own or overshadow their feelings with my loud wet tears. Is anxiousness why they get quiet and seem sad? Are they pulling inside, nervous about my emotions? We do know they get over loss faster than we do. Why does it matter?

Animals read our primary-color emotions like anger, happiness, fear, and surprise. The other designer-mauve feelings, like ambivalence, pity, or compassion, are more confusing and might just seem like anxiety to them. Anxiety is that catch-all place for things horses and dogs don’t understand. Of course, it makes them quiet. Half-closed eyes don’t mean the same thing to them as they do to us.

Can we tell where our feelings stop and our animal’s feelings begin? Rather than flood them, we could try to understand what it means to be a dog. And if that isn’t challenging enough, to understand what it means to be a flight animal who feels weakness.

The strange thing about a lingering death is that the world tilts on its side until the worst thing possible begins to look like a gift. Seen from that side, death is a sort of blessing. A sweet escape from a long slow debilitation isn’t the worst thing, but that’s human thinking and a question that never crosses their minds.

I confess I’ve shed an ocean of tears onto the shoulders of generations of slightly nervous horses and dogs. Did I use them as emotional dartboards? Probably but I’m not proud of it. The more I learn about animals, the more respect I have for their feelings. Working with rescues especially, I see so much practical resilience. If I could, I would take all of those tears and emotions I threw around back again. I would cry and commiserate less. I would praise more.

And I’d keep my eye on the bigger truth. One day, Lily will give mature guidance to an excitable pup. She is Essie Lou’s legacy.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Euthanizing and Herd Anxiety appeared first on Anna Blake.

June 10, 2022

How to Focus Simply.

I had just finished a lesson when another woman I knew at the barn came up to me with a sour face. Through pious lips, she said, “Can’t you do something about her hands?” As if finding fault in another somehow confirmed her own brilliance in the saddle.

She was referring to the novice rider in the previous lesson but it probably wasn’t a good time to tell her what I thought about her stiffness, her micro-managing, or most obviously, her judgmental nature toward other riders, and worse, her own horse.

I answered simply, “Yes, but we’re working on feet today.”

This isn’t meant to imply I’m a Zen master, training others because I was born in a saddle with a sparkly pink glow around me. I remember very clearly a time when it was critically important for my young horse to become perfect immediately so I could look like a better rider. Yes, that was me, thinking I wouldn’t have a problem with my hands if my horse would behave. Of course, my horse felt like he wouldn’t have to toss his head if his mouth didn’t hurt.

Learning to ride takes time. It isn’t that our right hand doesn’t know what the left is doing. It’s that they should both be planted in our armpits while we figure out where our seat is. We should be working on finding our calf to cue while our boot is quiet and still. We should be melting into the rhythm of the horse, whatever that means.

It might go like this. Can you feel your toes in your boots? Can you step into your stirrup and keep your knee soft. Can your inner thigh muscle soften? Can you feel your sit bones evenly on the saddle?

It is an evolved skill to feel your body on your horse instead of letting your brain chatter about how to ride. One involves your whole body and the other, just your frontal lobe. It matters because of the secret that no one tells you. You can ride, or you can overthink your ride, but not both.

Now, can you feel the outside edge of your foot on the stirrup, and what does that do for your knee?

Asking yourself these questions fulfills two purposes. First, it’s good to have a vague idea why your horse isn’t responding in the way you want and it might be you’re using him like a Thigh Master or banging away on his flanks without noticing. It bears repeating; step one is learning to control your own body. And a civilized conversation with a horse is out of the question if we can’t modulate the noise in ourselves.

The second purpose is more important. When we pay attention to our bodies, our mind becomes quieter. The cogs slow down, emotions soften, and our breathing naturally slows. Not to mention that feeling your sit bones lift and fall is a great distraction for timid riders.

Focus doesn’t mean having your eye on everything at once. That’s what is so exhausting about being a horse, that moment-to-moment vigilance for their safety. So we focus on one thing at a time, build some muscle memory, and patience with ourselves. We don’t need to be perfect, just self-aware. We have to feel the thing before we can fix it. For today, don’t fix anything.

When will we finally learn that criticism and blind repetitive correction don’t work? Asking too much every day doesn’t make humans or horses any stronger; it wears them out. Treat yourself like a talented young horse. Go slow and take the time to get it right.

Our minds will wander. Don’t punish yourself, take a breath and find your feet again. Just a kind rebalance.

Better to make our minds a cool oasis that a horse might like to relax in. Better to slow down our thoughts and feel our bodies. Consider riding in slow motion. Not stuck-in-the-mud slow, but the moving through water kind of slow. Let your horse carry soft cargo.

Put the neck ring on. Get in a safe place and give your horse’s mouth a rest. Then, instead of having a mental debate with yourself in your own head about what opinions you will post on social media later, simply ride. Notice your feelings but answer the questions with your legs and seat. Simply let your horse decide. Listen to your horse blow when his anxiety lessens, when his muscles relax. Tell him he’s welcome.

For all the times your horse has felt the dread he might be corrected or you have second-guessed yourself, just let it be simple. Don’t steer but instead feel every shift of weight. Notice small movements in your waist, the sway of your legs following your horse’s flank. Wait for his answer without interrupting him by asking again but louder this time. Enough intimidation. Enough self-incrimination. Let the horse’s answer be a good enough response, simply let him be right.

Let your mind be easy to read. Ask for just one thing at a time. No corrections, no layering on of confusing contradictions or judgment or anxiety. Just one cue. “Walk on, not that I care,” with an inhale. Wait for his answer. Let it be simple to say yes.

When we overthink, our horses notice our bodies go quiet but do they know where we have gone? Do we know, assuming we notice? Start again. Be here now. Can you simply feel your feet?

Our minds become simple for a horse to read by holding a light focus on just one thing. Let every cue wait for an answer, understanding that no answer is still an answer. Trade small calming signals back and forth, the kind of intimate conversation shared by friends.

Then one day, your horse takes a cue before you finish your thought. Or you soothe his concern before it becomes a conflict. One simple short ride at a time, and before you know it, neither of you remember where one of you stops and the other begins. It feels like acceptance, like both of you are right with the world. And you simply let that be good enough, too.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and barn visits. Information here.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post How to Focus Simply. appeared first on Anna Blake.

May 26, 2022

Affirmative Training: Navigating the Nebulous.

“I have a three-step process guaranteed to transform your horse into your perfect partner and it only costs ten thousand dollars!!”

How many of you are thinking about what you could sell? And how many of you have fallen for some sort of snake oil training approach in the past and are more than a little cynical now? How many sure-fire, they-worked-for-the-trainer, signature training aids that don’t work are left dusty in the tack room? How many video fails have you racked up because your horse goes off the grid in a minute by giving a different answer? Add to that all the free advice that doesn’t pan out.

It’s enough to make a rational horseperson, if there is such a thing, go a little crazy, which by all appearances, we are. We just want to get it right, but that seems to be a moving target that bumps along differently every day. Then, we’re so busy waiting for a bell to ring when we get it right, that if our horse gives us an answer that is perhaps a better answer, we don’t recognize it.

Go ahead and blame me. At each clinic, with people trying their best to learn it right, I still do things slightly differently with each horse. It was crazymaking if you’re taking notes. I didn’t get cruel or contradictory, but I do communicate individually with each horse. The door to communication isn’t well marked; I might have to ask a few questions first. If one door isn’t working, I’ll move on to another.

It’s required. Some horses are very young, some seemed older than their years. Some were over-trained in particular methods and some by a confusing variety of methods. Some were mares with hormones and some reacted to mares with hormones. Some of the breeds were old feral sorts and some designed by humans more recently. Some of the horses were visiting the farm and some lived on the farm which had been invaded by the visitors I just mentioned. Nothing was normal.

Even if the horses had been the same breed and sex, groups of horses will always have more individuality than conformity. Two of my personal horses are full siblings, and as different from each other as, well, my sister and I. Finding one training technique that fits all is as easy as finding one pair of jeans that we can all wear. Give it up. Humans were as unique and ‘not ordinary’ as their horses.

If we finally do get something trained with some reliable consistency, like trailer loading, it might flake out on a windy day or a dark night or the last day of a clinic. Why can’t anything thing be a done deal?

So there we are, tormented with whether our horse is right or wrong. But making a horse wrong does no good. Being wrong is just as much of a nebulous dead end for us. Can we give that judgment up for the time being?

Rather than looking for that technique that will not fail, wouldn’t we do better to get more comfortable with nebulousness? If we ask a dog to sit, and they do, the conversation is clean and over. Horses will never be dogs. Some dogs aren’t even dogs. Egads, more nebulousness?

Instead of praising ourselves for rescuing and rehabbing, training, and getting horses to do unnatural behaviors, maybe we give up the techniques that created their anxiety issues in the first place, and we sit back and listen. Could we teach ourselves to value our horse’s nature and exercise our own curiosity more? Because the elusive relationship we are all diligently working on will come the minute we stop pushing for a behavior we want more than our horse wants to give.

Can it be as simple as getting unstuck in judgment? Then rather than looking for perfection, we would look for congruity as a way of building trust. The most important starting point is to be in the conversation. If we are able to keep an open mind, we might recognize it when a horse gives us a better answer than the right one.

Does that sound contrary? There’s a bit of donkey in every horse. Their DNA is similar, cousin-like. Donkeys would suggest we give up the idea of being leaders and try to get along until we convince them they are safe with us. Donkeys hold that bar higher than horses. And there might be a little donkey in us humans, too.

We want an absolute answer from an animal that can’t give one. We have to be radical thinkers and find new creative approaches. If it isn’t about control, could it be about freedom? Instead of contorting their answers to our will, what if we release our minds to run free to do the unexpected? Would a horse read that as peaceful and curious rather than predatory?

While you’re at it, give up the idea that you’re doing it right or wrong. It just adds to a horse’s anxiety. Instead, of making every request a life-and-death referendum on your rightness or your horse’s ability to surrender, think whatever you ask is just a conversation starter, with the goal of two-way communication. What that means is we go their way, affirming their confidence, and understanding it’s a start to negotiations. If our way is safe, they will begin to trust and circle back to us. Trust must come first, then all behaviors are possible. We gain trust by offering it. We become trustworthy.

If we are ever to learn true listening, it will not be through telling these mysterious flight animals to obey us. Not by making these beautiful and fragile animals weak and anxious through leverage and domination, even if the domination is kindly presented. It’s our job to find the questions each horse can answer successfully, hopefully gaining just a small corner of congruity that we can build on. Call it shared safety. We become the peacemakers.

Instead of the eternal and childish “am-not/are-so” argument, what do humans have to lose by getting along? As any donkey will bluntly tell you, “We aren’t stubborn, you’re rude.”

It’s a fight we will never win as long as they are right.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and barn visits. Information here.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Affirmative Training: Navigating the Nebulous. appeared first on Anna Blake.

January 21, 2022

Calming Signal Substitutions: Helping Your Horse

Most of us are old enough to remember what a rolled-up newspaper is for. Wacking the dog, of course. Because dogs are destructive and must be taught to behave. The dog would have something in his mouth, like a shoe or a roll of toilet paper or a measly old sock on the way to bury it in the yard. But humans see that as a horrific offense against property and position! So, we cornered the dog and wacked them with the rolled newspaper because that “didn’t really hurt” and we only wanted to “scare them.” And if you came from where I did, it was an improvement over the previous weapons.

We were mad but would never admit it felt good to get that anger out. Some of the dogs rolled belly up, a calming signal when a dog wants to acknowledge another’s dominance. The frightened dog takes the most submissive position he knows, frantic to let us know he is no threat, even as a giant human looms over him, repeating “no” in a mean, slashing voice, followed by a few more wacks for good measure because cowering in fear wasn’t enough. Dogs may not understand what’s happening but they do notice a total failure in communication and demonstrate more calming signals.

A reminder: Frequently self-soothing, Calming Signals are an animal’s emotional response to their environment, shown through their body language as they transition up and down the spectrum between flight/fight/freeze and restorative phases of their Autonomic nervous systems. The signals are a message to calm us, to tell us we don’t need to be so aggressive, that the crouching animal means us no harm. (And a second reminder, the term Calming Signals was coined by Turid Rugaas, a dog trainer.)

Maybe the dog rolls back to his feet and urinates then. A whole new problem, we think, now the dog isn’t housebroken, the entire house is going to smell. Now it will never sell, not that we were thinking of moving. Submissive urination is a response to fear or anxiety, a calming signal. But you know what happens then. “Bad dog!” Wack, wack. Some dogs will shut down and stop playing. Some dogs have fear-biting in their future. Have you ever noticed how many tiny children scold dogs when they are too young to reason it? It comes out if a dog does a behavior that makes the child get a whiff of punishment in the air. When the child anxiously chatters about the “bad dog” without real comprehension, I wonder if they are innocently airing the family’s dark habits. How common must it be?

But I digress. The rolled-up newspaper wasn’t considered poor training for dogs back in the day. It taught fear and respect which was considered a plus. Come to think of it, it wasn’t considered poor child-rearing either but now I digress while digressing.

Some dog trainers always knew better and some owners always wanted to do better, and slowly the general population learned that exchanging a toy for that shoe was an option. Between the choice of grabbing the shoe and wacking the dog with it, or exchanging the shoe for a dog toy, more humans began to understand.

Was anyone curious about why the dog chewed things? Puppies are teething, obviously, but why adults? And that trade of a shoe for a toy, is good but was the initial crime a desire to destroy property, or was it anxiety, a cry for help? What would happen if we exchanged one method of self-soothing, chewing that Italian leather pump, for another, a kong toy packed with snacks or a squeaker toy? Less anxiety, time for the dog to deescalate on his own, and a call for us to resolve the initial core cause. Celebrate the new dawn on the planet! Humans evolved!

Sure, some dogs became compulsive chewers, yet another calming signal because the core issue remained, but it’s still an improvement when people let go of the newspapers we held every bit as tenaciously as any self-respecting dog would a stinky old shoe.

When will we figure this out with horses?

I don’t mean just when will we learn to stop wacking horses with ropes and whips, although that would be a huge change in basic assumptions. When will we finally understand that humans communicate in calming signals, too? If we use that shared language, we could help horses so much more. We could exchange one calming signal behavior for a healthier one, acknowledging the horse in the process. Trust begins here.

Example: Does your horse have a challenging time standing for the farrier? Do you think it’s bad training and we should dominate the horse into compliance? Seeing his side, it would be a death wish to surrender a hoof to a predator. Or maybe he has a sore foot and this is the way he can tell you he can’t put weight on it. Why pretend it’s military school and pop the rope clip on his jaw while holding our breath and feeling shame in front of the eyes of a thousand invisible but cackling railbirds? Why do we make it so hard for horses to try to communicate with us? Why accuse them of having nasty human motives, instead of learning their language?

The horse won’t stand still because walking is a calming signal for a horse, a release of anxiety, any horse will tell you. But so is neck stretching or softening their poll and jaw. In other words, chewing is a calming signal that allows a horse to relax. Would hanging a hay bag be a way of supporting your horse by offering an affirmative calming signal, like trading a toy for a shoe? For some horses, it solves the problem but if not, at least it gives us a non-violent option and perhaps buys time to deal with the underlying issue rather, than wack away at the surface. Can we let the horse self-soothe with a hay bag?

When we see stories about dogs being companions to lions, why do we think that that’s different than our own horses and dogs living with us? Do we ever think about the terrible risk animals take on trying to trust us?

In the past, we punished behavior that was embarrassing or inconvenient to us. We named behaviors good or bad rather than listening to the message. The problem is never that the horse just won’t pick up his feet. Their calming signals are often about pain or confusion, both lousy reasons to escalate to a fight. Why do we search for different training techniques designed to control the horse into compliance? Because it’s easier than focusing on smaller but more important cues that horses give us. Learning to understand calming signals is a call for us to understand the nature of horses better but it’s also a chance for true two-way communication.

If only they can calm us down.

…

Anna Blake for Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and barn visits. Information here.

Want more? Join us in The Barn. Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live-chats with Anna, and the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Ongoing courses in Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, Fundamentals of Authentic Dressage, and Back in the Saddle: a Comeback Conversation, as well as virtual clinics, are taught at The Barn School, where I also host our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find over a thousand archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation or lesson, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Calming Signal Substitutions: Helping Your Horse appeared first on Anna Blake.

January 14, 2022

What Does it Mean to be Domesticated?

If you have been reading along for the last 1300 or so weekly essays of mine, you know sometimes I get testy about words. I decry those insensitive people who “desensitize” horses. I have no respect for those who hijacked the word “respect” to justify disrespecting horses. Both of those word abductions have sent me where I am currently, deep in a rabbit hole about whether horses are truly domesticated. Rabbits, by the way, are categorized as both wild and domestic. I notice when rabbits get out, most turn feral pretty quickly. The drama is short-lived because rabbits are prey animals with fragile necks and usually get eaten before they can raise a flag and claim independence. But were rabbits really tame in the first place? It’s pretty easy to catch wild baby rabbits because they play dead when they’re afraid. Is playing dead the same as being domesticated?

Most dictionaries say a domestic animal is defined as “an animal, as the horse or cat, that has been tamed and kept by humans as a work animal, food source, or pet…” And I have a problem. Are cats domesticated? Mine still hunt moths and mice, splatter-splat. It seems a pretty shallow definition to call a cat who lets you live in her house domesticated. Doesn’t that make the human the domesticated one if we’re talking cats? They train us to be their work animal. We feed them at the crap of dawn, to clean up after them, and the dogs will be the first to tell you cats are wild and unpredictable alien creatures who cannot be trusted, no, not even a minute. “Bark. Barkity-bark.”

Wait! Then the dictionary definition of domestication continues, “…especially a member of those species that have, through selective breeding, become notably different from their wild ancestors.”

Okay then, are dogs domesticated? The chart says yes, but I have one that looks like a short hoagie-shaped fox who’s never been reliably housebroken, leaving his signature like a respectable indoor wild dog. Wolves and Pomeranians have good hair in common, but every time I watch a sled dog team, I think no way, they’re not lapdogs. I got the chance to go into an acre-sized natural kennel with a large pack of husky sled dogs. I sat with my hands in my lap, watching their calming signals while they crept closer and checked me out. Surrounded as they carefully sniffed me, I was definitely the blushing awestruck domestic one that day. Sure, lots of dogs have been sitting on our laps eating cheese for hundreds of years but I’m not sure if we domesticated them or our furniture did. I confess, at a certain age, a dog can get me to drive him to a fast-food drive-thru for a burger. It’s usually on the last trip to the vet. Generations of dogs have taught me how to behave and made me their pet. Surviving them is my greatest human accomplishment.

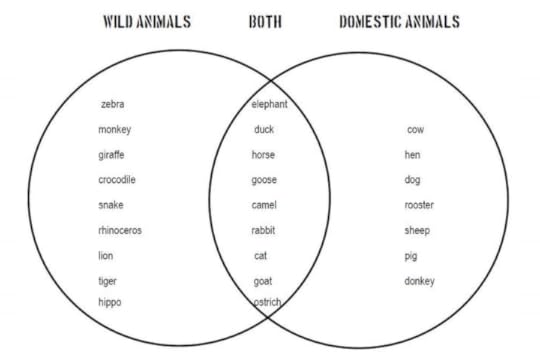

I found this diagram online. What I like is that it allows for a gray area between wild and domestic.

From the bottom of my rabbit hole, I ask in a loud, somewhat sarcastic voice, how are monkeys wild? They wear suits and smoke cigarettes; they look like your uncle Fred, down to the nose-picking. Who thinks sheep are domestic. Okay, I still hold a grudge against a Suffolk ram who broke my nose when I was five but my friend’s herd has a better recall than your dog. Maybe sheep are domesticated, but the snakes I see inside don’t look wild, so much as long lanky Zen masters who tie themselves in yoga knots and fast between feast days. Do they meditate on mice?

They are easier to catch, but does domesticating an animal improve them? What is lost? Yorkshire terriers were half-wild farm dogs who chased rodents all day before we turned them into purse dogs.

That pesky definition again: A domestic animal is defined as “an animal, as the horse or cat, that has been tamed and kept by humans as a work animal, food source, or pet, especially a member of those species that have, through selective breeding, become notably different from their wild ancestors.”

Of course, it’s horses that I care about; that I make no bad jokes about. Most definitions leave no gray area, horses are domestic animals. That humans changed them centuries ago from instinct-driven prey animals to beasts of burden. And we’ve selectively bred them, some to pull heavy loads and some small enough to fit into coal mines.

I’ve worked with wild horses: Mustangs, Kaimanawas, Brumbies, and even met a herd of Przewalski’s horses who spent much more time trying to get along than get away. Technically they are feral horses, but if feral horses are not domesticated, why do they look so similar to our horses? Why do they settle into captivity so quickly, and many times, are as easy to train? Why do our domestic horses are need fences to hold them? We like to think horses volunteer by coming to the gate for a carrot. Even if the pen is acres large, a horse knows he’s captive.

We want to think that draft horses are “gentle giants” when their flight response is no less sensitive than a hot-blooded plain-speaking Arabian. We want to think ponies are children’s horses when they have no special skill and a golden-retriever-of-a-quarter-horse would be a kinder, safer option for kids.

Why do so-called domestic horses still spook, listening to the environment for fear of predators instead of our voices? Why do our horses show anxiety when we stand too close? If we’re honest, we value “tame” horses, so shut down that their eyes look dead as a baby rabbit.

It matters because we make up untrue stories. We imagine horses into stuffed toys to cool our anxiety. We talk loud to dim their intelligence. We micromanage them to sublimate their strength. We overlook uncomfortable emotions to ignore their physical pain. It’s as if the more we believe horses are domesticated, the less we have to understand their true nature. It matters because horses are not all thriving under our care. Sometimes our drive for excellence in training turns into an effort to change who horses fundamentally are.

Here is a solemn salute to the many horses, especially mares, who have refused to submit to domination, prey animals who refused to be slaves to our anger and force? They might say, “What if horses are not domesticated so much as more tolerant than other wild animals?”

Would we be more patient or respectful of horses if we saw them as “wild” animals? Domestication is a statement that we own their life. Is it worth it if we diminish their autonomy?

To understand that a horse is a horse is to respect their sensitivity, to celebrate their hyper-awareness of the environment, and to never get complacent about the simple tasks. That we never become complacent about what it means to surrender to a halter, to give a hoof to a predator. It isn’t our right. Be humbled by that.

We are the ones who must learn respect. Not with the dominant use of discipline or with aggressive neck-clinging love. We must learn old-fashioned respect. We must value their autonomy.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and also, barn visits. Information here.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post What Does it Mean to be Domesticated? appeared first on Anna Blake.

January 7, 2022

Finding the Ground But In a Good Way

Our T’ai Chi master told us to drop our weight? I was barely legal and my fledgling art career was doing so well that I didn’t own a car. The class met in a church gym, he stood in front with his back to us and the small class mimicked his slow-motion movements. He told us to root deep to the earth, shifting our weight a pound at a time to one foot to release the other for a conscious step. I was hooked, totally consumed with T’ai Chi’s beauty and quiet power. Pretty soon I was practicing shifting my weight at bus stops and while cooking my dinner. T’ai Chi was perfect for a fidgety introvert. T’ai Chi defined my life, two nights a week and Sundays in the park. I’m that sort who teeters toward the fanatic and I progressed quickly, eventually teaching. Besides, I didn’t have a horse.

Looking back, I think it was the first time I ever met the inside of my body. I knew kids who grew up in sports or dance and had a natural athleticism or a physical awareness that was foreign to me. All I did was run around like a headless chicken, writing emotional poetry while being distraught about life. In other words, I was attracted to Eastern Philosophy and activity for the same reason most people were back then. I was missing something I couldn’t name, but there was a thing that happened when I felt my feet on the ground, when I focused on what we called our tan t’ien, our energy center, and followed my breath. Finding the ground let me quiet my mind.

Eventually, I was able to buy a horse and stopped T’ai Chi classes, but it isn’t any easier to give up T’ai Chi than it is horses. Chinese say that in the beginning you must call yourself to practice the art but soon the practice calls you. Even now, my sword is in my writing studio in case I need to stop thinking. I consciously shift my weight to focus while giving riding lessons. I teach Push Hands as a rhythmic way of understanding rein contact. After all, isn’t dressage a kind of mounted T’ai Chi?

In the horse world, the closest we come to talking about being grounded is telling stories about unplanned dismounts. And boy howdy, do we tell stories. We fill the silence with words and noise and emotions. Worse, our hands get busier with each word, more nervous when it’s quiet. We lift our hands as high as our shoulders as if horses were blind. We sing, we chatter, we cajole. We talk to our horses to make ourselves breathe, to make ourselves less nervous, to encourage ourselves onward. We think the horse likes us to talk but it calms us more than them.

If the horse has something to say, it’s hard to get a word in edgewise. There is a disconnect. Our chatter exists in our over-active, well-oiled frontal lobes. Horses don’t have that same anatomy. While we’re running laps in memory or dreams or composing grocery lists, the horse is feeling the earth, the wind, sensing movements in the environment. The horse is listening to the world beyond words. We see a metallic wrapper blown against the fence. It startles us more than him, because of that pesky grocery list. As long as we calm ourselves, the horse doesn’t care how.

Maybe you think it’s your voice that cues your horse. They are certainly intelligent enough to learn words, but it was your feet that rule the moment. We can forget that because our feet are so far from our brains. Exhale and send your brain on down.

Is your horse more interested in the busyness of the world than you? Quiet your mind by letting it rest in your feet. Feel your toes. Let your heel settle into the earth. Do you lunge your horse? Don’t chase him. Stand still so he can find his balance. Is he a little fussy at the mounting block? Park your feet and become reliably still. Want to connect with your horse? Make your breath an anchor by inhaling into your toes and then trust the earth to send the message. The air is unstable. The earth is our connection with horses, it is trust in solid form.

It’s true in the saddle, too. Have you forgotten? Ask a friend for a pony ride. Schedule a lunge lesson with a trainer. Climb on in a safe place like an arena and let your hands rest on your thighs or use a neckring. Look, mom, it’s no-hands January.

Inhale as you swing your leg over your horse’s back and then settle into the saddle. Check your thighs. If they’re tight, you’ll be a bit suspended over the saddle. Truly check because you’ll feel unstable to your horse. Can you tell for sure? Connect your feet to the stirrups with a light tap. Feel your toes, putting your weight to the outside little toe. Does that release your knee a bit? Did your horse relax some? Is your toe sticking out far enough to catch on a fence post? Point it forward, please. You might have to remind yourself again soon, until the tight muscles release. Are you back in your brain thinking, wondering if you’re doing it right, worrying that you are out of control? Put your mind back in your feet, your thighs, your seat. A light tap to the stirrup, please.

Let the saddle hold you but carry some of your weight in your feet. Enough pressure in both stirrups to help your horse carry you. Feel your horse’s movement ripple through your body. Surrender because, in order to lead, we first follow their movement. We don’t oppose force. Wait, that’s T’ai Chi (but it’s also how to start an affirmative ride.) Your brain is begging you to come back and talk but trust your horse. Let him have his movement, let your seat follow. Your hands are screaming to grab, your brain feels deserted. Good, trust the part of you that connects, not your hand to the bit, but your seat to his back. Let your horse rock you in his stride. You’ll never feel safe in a gallop if you don’t trust this walk. How are your thighs? Are you deeper in the saddle, has your waist become fluid? A light tap of the stirrup, feel your little toe. Connect with the ground through your horse.

A slight turn of your body, lead with your tan t’ien, your solar plexus. Think of it as a headlight that your horse moves in. Feel your knees as a flexible tunnel for your horse moving forward, your shoulders following. Ignore your twitchy fingers. Ride the inside of your horse. Halt by softening your seat to stillness and exhaling. Acknowledge your breath as an anchor to the ground for both of you.

Crave the body-to-body conversation, in the saddle or on the ground, your tan t’ien to your horse’s. It’s the connection you can’t name because it comes from the earth and not your brain. Feel unity, each of you autonomous, but partners in movement.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and barn visits.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and hosts our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Finding the Ground But In a Good Way appeared first on Anna Blake.

December 31, 2021

Auld Lang Syne Horses

I’ve heard it a couple of times just today: “As we head into the third year of Covid…” It makes my lungs freeze and my feet stick to the ground. They are playing Auld Lang Syne, “Old Long Since”, and I’m re-running my last year, and dreaming up goals for the new year. Covid has kept me on the short end of my driveway and I’m melancholy. These years of my life will not come back and I have wandered a distance from any age that could be called midlife. These years have been stolen from all of us, it’s true, but just for tonight, I’ll let it be about me and the ones I’m missing. I miss your horses.

When I started training professionally, the first advice I got was don’t be friends with your clients and don’t fall in love with their horses. Smart thinking. I’d been self-employed long enough to know that money exchange makes for uneven ground in friendships. When I was a riding student, I loved my trainers because they talked to me about my horse but I knew we weren’t friends. I paid them to talk about my horse, and that’s my job now. Clients come and go for many reasons and I wish them well. Life is change. The problem is I love their horses.

I am certainly clear that loving the horses I work with is a foolish abuse of my professional boundaries. Don’t smile, don’t think it’s a dream job, and understand that the love trainers like me feel isn’t all sweetness and kisses. It’s fierce and unreasonable. We love “bad” horses, chronically lame horses, and sometimes we’re like women who try to fix their boyfriends; we try to save broken horses that remain lost. We’re wholly focused on making things right for the horse, our personal feelings be damned. It takes a ridiculous amount of energy to hold your heart open in a world of imperfect owners and beautifully sensitive horses you don’t own, but the real problem should be obvious. Horses owe us nothing. If your heart isn’t open to the horse you’re training, you just don’t get their best work. You will never get more out of a horse than you are willing to put in.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And never brought to mind?

It was years ago at my first large clinic. I hadn’t planned the start well, and too many horses were in a too-small indoor for an obstacle clinic. Before I could begin, there was a problem. Over toward the wall, a bay mare was being corrected by her owner. The rope snapped as she was repeatedly chased back, but her hind was already against the wall. There was no place for her to go but up, and she was mad. She couldn’t wait. Without a greeting to the group, I asked in a loud voice if I could have a demo horse and caught the eye of the mare’s owner. He looked half relieved and half insulted as he handed me her lead. Not a good start. I took the end, let the middle of the rope hit the ground and her hooves came to rest a second later. All I did was call a truce. It wasn’t magic and she didn’t thank me. There was no romance. But it was beautiful to see her pride, wonderous to watch her breathing go deep as she stood square and tall, as noble as a queen. I knew better than to insult her by petting her but my eyes followed her all day. Like we were alone in a smoky crowded bar. Pathetic.

I visit a few sanctuaries, usually to do a training for their volunteers. Places like that are thick with love because they are run by hopelessly idealistic people. Sanctuary means horses live free of intervention as much as possible. They are horses loved selflessly from afar, but that’s the beauty. Horses doing no more than grazing in herds with little human encumbrance. They are living, breathing fairytale horses. Everyone should love these horses… by sending money.

Sometimes I stand with a client and her old campaigner. I’m the translator, the elderly horse shows me every pain he has, he shows me his exhaustion and how far he has traveled, a flight animal with no escape. He fears laying down for a predator might come. We become complacent about his frailty but he cannot. His human loves him so hard it blinds her to his pain. He means so much to her that she can’t say the word that will set him free. In this precious moment, my ghost herd gets restless, stomping about in my heart until I think my chest will crack open, and I breathe and ask quiet questions until the owner can find her words. Loving elders takes the most courage of all.

My softest spot will always be for stoic horses. The ones who pull deep inside, as still as rocks. They keep their emotions hidden in hope of being safely invisible. They draw me into their silence, as I wait for them to close the distance between us. They will not be hurried and I don’t want their surrender. It’s a war of quiet patience, waiting for a crack in his defense. My love will not save him, but respect can give him space to mend himself. I breathe, a predator trying to sell the idea that a horse can be safe with me. Another deep breath as I watch for a flick of an ear or slight release of his tail. Everything begins with acceptance of who the horse is right now and prioritizing their confidence enough to wait.

Love without possession definitely has its downside. Sometimes you have to trust that they’re God’s horse, but in truth, are any of them are ever really ours? We’re always training for the next horse. It’s a pay-it-forward world we’re building, with gratitude for all horses have given us over centuries. We’ve always used them hard. I surely see the damage we’ve done; hear the horror stories about trainers who have failed them. Horses are heartbreakers and there’s much sadness but our sympathy doesn’t help. We must do better.

All the time and effort are returned tenfold in that instant when I’m reminded that each horse, without exception, has a heart that will never be tamed, never owned by another. Lucky me, it’s my job to fan that spark within them that is forever free; to find the autonomy of that first bay mare again… in old campaigners, frightened rehomed horses, and unnaturally quiet geldings.

It’s New Year’s Eve and I’m a whiny old horse-crazy girl missing the horses I didn’t get to meet the last two covid years. Silly me. Here’s to horses!

We’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet

For days of auld lang syne.

(If you see me again, there is every chance I won’t remember your name but don’t take it personally. I’d still like to know how your horse is doing.)

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward Training. Available for clinics and barn visits with safety precautions galore in 2022.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Auld Lang Syne Horses appeared first on Anna Blake.

December 24, 2021

A Love Letter to Dirt.

It’s the eve of Christmas Eve and I’m worried about my dirt. Maybe the world has bigger problems and maybe it doesn’t.

It’s a toasty 49 degrees with 30mph winds, with gusts to 75mph overnight. Not normal Colorado weather, but that’s seems to be the weather everywhere these days; not normal. My farm’s dirt could never be called soil, even on a good year. This fall’s been paper-dry and the wind has already stripped away even the heartiest of weeds. Forget the grass. I’ve reseeded several times over the years with less success each time. The dirt is as fine as dust, deep and soft and so dry that when water from the hose trails between tanks, the dirt curls up around the moisture like a long thin snakeskin, crinkled and lifeless.

We’re at a little over 6800 feet altitude and just at the edge of desert. I mourn the skeletons of four large trees finally chopped down this year after I surrendered hope they might be partially alive. Now the power company claims they need to destroy the cottonwood by the pond. When it’s gone, we’ll have an unobstructed view of the wind farm’s huge black poles and power lines scribbling out Pikes Peak.

The only large tree left is by the barn, due to my diligently dumping and cleaning water tanks nearby. On good years, the pasture has wildflowers, some frail prairie grasses, prickly pear cactus. Newcomers think this land is good for grazing cattle if they haven’t talked to the county extension agent. With horses, we know we’ll feed hay year round and in these last years, I’ve gotten so protective of the pasture that I use it less and less. I spread manure over every square inch. It isn’t pretty but I hope to thatch down what ground cover there is. Posts sunk deep in cement have resurfaced, inches above the ground, the wood faded and broken. The truth is I lose a little more of the farm every year, from the top down. If you have horses none of this is new. Erosion, drought, bomb cyclones. Hay prices, hoof issues, fence repairs.

Town is creeping up on us from three directions and there are days when major repairs seem like a bad investment. Sure, I could move back to the Pacific Northwest. There are places in Australia where the red color in the dirt is impossible to “get out”, places in New Zealand where you can’t find the dirt through the lush vegetation. And then there is Scotland, full stop. This flat windy treeless prairie isn’t as beautiful perhaps, but I don’t want another farm. I want this one to live.

Town is creeping up on us from three directions and there are days when major repairs seem like a bad investment. Sure, I could move back to the Pacific Northwest. There are places in Australia where the red color in the dirt is impossible to “get out”, places in New Zealand where you can’t find the dirt through the lush vegetation. And then there is Scotland, full stop. This flat windy treeless prairie isn’t as beautiful perhaps, but I don’t want another farm. I want this one to live.

It’s easy to love nature, but it was horses who made me love dirt so much. Some horse owners grimace when horses drop and roll, as if grooming or baths were ever meant to be permanent. As if we were afraid of dirt. If you have a donkey, it’s a timed event, from release to roll in seconds, as if they’re trying to get the stink of grooming off them. A drop and roll is a reset of the horse’s autonomic nervous system. If we were smart, we’d ask for a roll before competing or taking a trail ride.

Instead, we fuss with their hair and try to avoid the ground. Don’t fall, don’t get dirty, don’t step in that. We keep our heads high, consumed with thought bubbles: what we think, what we think other people think, what we make up that our horses think. Thought bubbles about getting older, about our horses changing in ways we can’t stop, and bubbles with mathematical equations of all we’ve failed or lost. You might as well be outside in that wind tonight.

When we’re new to horses, we get “psychological” about horses and search the cosmos for messages. It’s the dirt that brings us back home, settled and present. Horses know. They depend on the ground to hold them, it’s the ground that gives them flight. If you watch horses, they lose confidence if they can’t trust the earth. It’s why tarps and bridges are obstacles to them and why icy ground frightens them. Watching horses, you can’t miss their profound connection with the earth.

Yet, when we want to connect with horses, we ignore the dirt. We hug and kiss them, our hearts swelled up thinking that their closed eyes mean love returned and not distancing or evasion. We try to love them into submission. Or we use semaphore communication. We wave our arms, use whips or sticks with bags to make our arms longer, and pull their faces with ropes to disconnect and unbalance horses.

No wonder we think it’s magic when horses come to us when we’re quiet or follow us silently at liberty. In spite of all our chatter and rattle, horses continue to try to connect with us. If we were on the right track, we wouldn’t see calming signals constantly. We get so excited to see the horse’s message of anxiety that we don’t hear the intent. Calming signals are the horse telling us that they are no threat, they are prey and mean us no harm. They send the message that we don’t need to be predators. It’s them trying to calm us!

Maybe we need to pay more attention to dirt and less attention to our stormy thoughts.

I’ve asked horses to prove it to me repeatedly. When I halter a horse, step one is to breathe and feel my toes inside my shoes, conscious of the ground. I notice the horse comes. When I’m holding a lead and the horse is stiff with fear, looking in the distance and ready to spontaneously combust, I step to the end of the rope and feel the dirt under my feet. It settles my mind, and the horse calms quickly. I want to think that I’m the safe place, but what if it’s really the reminder of dirt under our feet that gives us each our balance and peace?

We are on the brink of better communication with horses; it’s here with us but we haven’t “discovered” it. Science moves us forward but only because science is also connected to dirt (the natural world.) Research tells us that trees communicate with each other through the earth. We know that each of the horse’s senses is more acute than ours. We talk less of their sense of touch, but those hooves are sensitive. Why do we use our hands, an appendage that horses don’t have, when they listen to our feet and match our stride naturally. When all the human chatter settles, isn’t the dirt under our feet the most primal connection with horses?

It takes a while for the love to settle, for us to realize that horses are flowers of the dirt beneath them. And so are we, if we let the earth hold us and support us. If we love dirt for its hold on us.

The holiday greeting is more literal than we overthink it to be. Let the emphasis on that second part. Peace on Earth.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post A Love Letter to Dirt. appeared first on Anna Blake.

December 17, 2021

Patience in Real Time

A clinic organizer was telling me about a trainer she brought in, someone whose approach was significantly more aggressive than mine. I asked how it worked to have such different approaches for the same riders and she said, “Oh no, he has the same training theory as you do. He told me that for a clinic he has to get results quickly so people don’t get bored.” My next question was going to be about integrity, but I bit my tongue. Is this who we are? Don’t even start with me about mustang challenges, colt-starting challenges, or the dreaded comeback challenges. We’re impatient enough without baiting each other on.

What is it about ponies and minis? We use horrible training methods and then call them stubborn. We tease them with sweets or dominate and manhandle them in ways we wouldn’t dream of with a seventeen-hand horse. Over the years, I’ve retrained quite a few. It’s slow work but it’s a debt we collectively owe to these intelligent, athletic, and sensitive horses.

Meet Bhim, who came to my barn for a month of training in 2013. Yes, he’s still here, and don’t you dare call him cute. Look at his face, really see him. He is not a horse to underestimate. Let the insulting diminutive words rest. Hold your “what a sweet baby” comments. This horse has forced me to redefine my approach with training again and again. And if there was a patience challenge, we would be front runners.

I put Bhim in a pen when he first arrived, with Edgar Rice Burro keeping company in the next run over, like usual for visiting horses. Bhim hated both of us. At the end of the first month, I hadn’t made much progress, but I’d spent hours listening as he had told me his history. I was intrigued by his strength of will against giants. He wore his fear as bravado. And maybe he reminded me of someone.

He stayed in his sympathetic system; never frozen, but always in flight mode, and ready to fight. He didn’t let down. I never saw him blink or eat, and mucking his pen frightened him. I spent time like it was free, I moved slowly as he insistently bolted. I refused to corner him. I stayed quiet, breathing slowly, reading barely-visible hints at calming signals. Bhim only knew one volume, a primal scream, and he was stuck. By the second month, I was able to halter him in forty minutes or so. I didn’t train him, mind you. He taught me a position where he allowed me to approach, but it was easy kicking range and we both knew it. He demanded my trust first.

Instead of Edgar simply calming Bhim as he had every horse before, Edgar became his protector. Donkeys can be territorial, but this was different. Edgar was still my training partner, but with his head through the fence panel, he breathed calming signals for Bhim. Edgar Rice Burro, who has never liked horses much but is never wrong, let me know that it was time he had a horse of his own. I’ve never been able to say no to that donkey. We adopted Bhim, partly because Edgar wanted him safe and partly because I knew it was going to take more time than was reasonable. Don’t get all weepy on me. Trainers can’t save horses in need; there are too many. I say “no” hundreds of times for each “yes.” My last “yes” had been Edgar, years before.

Bhim and Edgar soon shared a pen. Edgar used his body like a reverse round pen, standing still as Bhim and I slowly circled. If I took Bhim out on a line, he usually got away from me. We spent a few months finding a way to make trimming easy for him. I didn’t train him, mind you. He told me what he could tolerate and that’s what my sainted farrier and I did. It wasn’t perfect, but it got easier each time we didn’t fight about it.

Affirmative training is collecting good experiences with the horse. It isn’t that we train canters or picking up hooves, horses know how to do that. We work calmly, not allowing the horse’s anxiety to overtake them. We train that predators can be trusted, building their confidence so horses can volunteer to work with us. We always remember that intimidation and punishment destroy trust. Humans and horses learn to be reliable over time.

Every few months Bhim would have a reluctant breakthrough because I have glacial persistence. One year I was able to give him a brief massage. He never relaxed, but his eye flickered for a moment, then went hard again. I couldn’t catch him for a few weeks after. Each time he softened a little, he’d act like he’d had an embarrassing one-night-stand and pretend he didn’t know me for a while.

Training should never be a competition. It takes the time it takes, no matter who you are. When clients get impatient, I’m stumped at why anyone would think working with horses wouldn’t take serious effort and a strong heart. I blame these stupid challenges. Don’t take my word for it, read the horse’s calming signals. Hurry the day when outdated fear-based training is gone; when we stop equating intimidation with respect and mistaking shut-down fear for trust.

How much of the present with horses do we hurry through for the future? Horses need time. Rarely as much as Bhim, but all horses are hardwired for flight. It means they’re easy to intimidate. Children can do it. Getting along with horses is the real skill.

I had to look at the calendar to find the year Bhim came. Seeing the names of several other horses who arrived that year with one problem or another brought back memories, each horse an individual, but I always asked the same question. “Can you trust me?” They moved through my barn to new homes and others arrived. I love the slow-dance rhythm of training.

Bhim walks now. Not a ground-covering gait, he’s relaxed, almost slow. Sometimes when I’m hanging hay nets, he presents his ears for a scratch, but just one. I’m still the only one he allows but I can halter him in a relatively normal way. He gets a bit of bodywork. Sometimes I think I see a spark of a volunteer from him. He’s always tried his best. One afternoon last summer, I sat down on a bucket (he doesn’t like people lurking above him), to take his halter off. Bhim lingered for a few moments. He yawned for the first time. I gave an exhale and he yawned a few more times. Then he ignored me for two weeks.

It was never personal. None of it was bad behavior. It’s who he became to protect himself. Bhim’s more horse, inch for inch, than a warmblood. These days, his resistance is less fear and more habit. Edgar is getting older, so Bhim stays close. I’ve changed more than they have. I’ve learned how to listen smaller, to trade time for their anxiety. We don’t walk on eggshells but we don’t pick fights. I thought I owed Bhim a debt for what other humans had done to him, but really, I owe him a debt for what he has done for the other horses I train. If you’ve read along or worked with me, you owe him as well.

Bhim would be the first to say it isn’t easy being a trainer’s horse. This woman never gives up. But we live in horse time, where progress is measured in inches and years.

Click to view slideshow.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post Patience in Real Time appeared first on Anna Blake.