Azadeh Tabazadeh's Blog

June 18, 2017

Richard Turco-A trip to Bear Valley Springs

I am deeply honored to present a talk this coming Saturday at Bear Valley Springs, a wonderful retirement community where my UCLA Ph. D advisor, Professor Richard Turco, and his lovely wife, Linda Turco, now reside. Thank you Rich for inviting me! You are simply one of the dearest and kindest human beings I have ever met and worked with. The world needs more people like you to teach, inspire and lead the way.

Rich has an uncanny resemblance to Kirk Douglas. Ay my Ph. D ceremony in 1994 my father thought he was the legend himself. To me, however, Rich is a true steward of the Earth and a legend beyond reproach.

Scientist to lecture on her escape from Iran

The post Richard Turco-A trip to Bear Valley Springs appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

May 9, 2017

My Story: From Iran to NASA and Beyond

It’s an honor to present my book, The Sky Detective, at my alma mater on May 19 ( Room 365, Humanities Building). First time to give a talk in the Humanities Department of a major university. I hope the trend continues!

The post My Story: From Iran to NASA and Beyond appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

February 28, 2017

The Huffington Post: The Sky Detective

Read the article at the Huffington Post about my book: The Sky Detective.

The post The Huffington Post: The Sky Detective appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

February 12, 2017

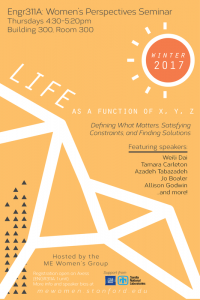

Life as a Function of X, Y and Z

I am giving a talk at Stanford this coming Thursday at 4:30 pm: Life as a Function of X, Y and Z”.

Come if you are a young woman and would like to know how to balance work with family life. X and Y are the independent variables: Your career and your family. X and Y, however, depend on Z, which is the balancing act of managing the two. Getting the Z right is what gives your life meaning and makes you feel happy, satisfied and content.

http://stanfordmewomen.weebly.com/seminar.html

The post Life as a Function of X, Y and Z appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

July 6, 2016

Is sexual harassment the reason why women quit science?

Is sexual harassment the reason why women quit science?

I’m afraid the discouraging press coverage regarding this topic in recent years has brought undue harm to young women who wish to pursue scientific careers. Check out a recent NY Times article regarding “sexual harassment” in science:

She Wanted to Do Her Research. He Wanted to Talk ‘Feelings.’

During my time at UCLA, NASA and Stanford, I did not experience nor do I view sexual harassment to be a major issue for “women in science”. Maybe my upbringing in Iran, where I witnessed everyday sexual discrimination, has conditioned me to not pass judgement about “men in science,” which in my case have all been tremendously professional, insightful, and encouraging!

The post Is sexual harassment the reason why women quit science? appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

June 18, 2016

LOS ALTOS LIBRARY – SYRIAN REFUGEES

“I will be on that boat attempting to escape the madness. What about you?” I asked an audience of about 100 people on June 8.

I ended my my Book Talk, sponsored by Los Altos Voices for Peace, with the photo and the question above.

Photo shows desperate Syrian refugees on an overcrowded boat hoping to cross the sea and arrive on the Greek island of Kos. The tragic events unfolding in Syria reminds me of my own journey of escaping Iran for a chance to find peace elsewhere in the world.

The post LOS ALTOS LIBRARY – SYRIAN REFUGEES appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

May 25, 2016

Return to NASA

Yesterday, I presented a talk at NASA in celebration of the Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month. The topics covered ranged from showing a hula dance, performed by the Nixon Elementary kindergarten class, to the escape route that my brother, Sean Taba, and I took to get smuggled out of Iran in 1982. I was re-invited by the Asian-American advisory committee at NASA because our story of escaping a dictatorship and finding success in America is one that is shared among many nations.

The post Return to NASA appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

March 17, 2016

Book Talk at NASA, Fire Alert, and More…

Book Talk at NASA on March 15 organized by Women’s Influence Network (WIN). It was a wonderful event and over hundred people showed up. However, I didn’t get a chance to finish my talk. Why?

I had a slide up about the Cinema Rex fire/arson on August 19, 1978 in Abadan, Iran that claimed many lives–an event that many historians believe was the key that triggered the 1979 Iranian revolution. As I was discussing the event a lady rushed up to the stage, grabbed the microphone and said, “Smoke is coming out of the control room. Please leave the auditorium immediately.”

I am going back to NASA to finish my talk, hopefully soon. Stay tuned!

The post Book Talk at NASA, Fire Alert, and More… appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

March 11, 2016

March 8, 1979: Anti-Veiling Protest in Iran

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/march-8-1979-anti-veiling-protest-iran-azadeh-tabazadeh

A travel down the memory lane! I was fourteen years old at the time of this protest, which I attended with my mother, Azar, and a group of her friends. Despite Ayatollah Khomeini’s promise that he will be a religious leader, two weeks after his arrival in Tehran on February 1, 1979, he began preaching Shariat, mandating all women to wear the veil. Over 100,000 men and women took to the streets of Tehran to protest against veiling on March 8, 1979–International Women’s Day. Initially, the Ayatollah backed off, but sadly within a year veiling became mandatory.

Below, I share an excerpt from my memoir–The Sky Detective: How I fled Iran and Became a NASA Scientist–recalling the events of March 8, 1979. This excerpt is from the “Revolution Madness” chapter:

During the next week, Mamman and her chic friends, dressed in high fashion European clothes and dark sunglasses, become regular participants at street rallies, protesting against mandatory veiling. According to her, they have to wear ridiculously large dark sunglasses to disguise their faces from the enemy—the regime insiders—individuals who are dressed in civilian clothes to secretly photograph people. It seems as if a turban has replaced a crown, but nothing fundamental has changed in Iran. Before, people were scared of SAVAK, the shah’s secret police. Now, just a month after the revolution, the same people are again afraid of yet an unnamed secret police of some kind.

One day, Mamman is late coming home from one of her frequent outings with her girlfriends. Worried thoughts grow in my head as I watch Afshan play with her Barbies. She has setup her two-story pink Barbie house at the corner of the kitchen and is pushing Ken’s camper truck to approach and park in front of the house. Today, he’s a lucky man, for I can see five well-dressed Barbies around the dining table waiting to have dinner with him. Last September, right after we returned from England, I gladly donated my Barbie collection to Afshan, basking in her love for weeks afterward. For Afshan’s sake, I hope the ayatollah doesn’t declare war on Barbie and Ken.

For the zillionth time, Afshan looks up and asks, “Where is Mamman, Azadeh? Don’t you think it’s getting too dark out there? Are you sure she’s okay?”

Before I have a chance to respond, we hear Mamman’s car grinding and growling outside. Afshan runs out as I sigh and stare up at the clock and then at the large, empty bag of potato chips in front of me next to a bottle of consumed Coca-Cola.

Minutes later, Mamman walks into the kitchen and puts her notepad down. “I’m sorry to be late, Azadeh. I went to a craft store after the rally to pick up some materials.”

“To pick up what?” I ask, staring at her. “We were so worried about you.”

Mamman tries to stroke my hair, but I recoil and look down, only to see the words on her notepad, written neatly in oversized letters in her handwriting: We Have Two Choices—Freedom or Death—Nothing More, Nothing Less.

The realization that I may soon lose my mother at a rally cuts through me like a knife. My eyes well up with tears, thinking I’d rather have my mother alive and veiled rather than defiant and dead.

“Azadeh, would you like to help me make a banner with these words?” Mamman asks as she tucks my hair behind my ear.

I wipe my nose on my sleeve and nod. Mamman unrolls a white piece of fabric on the kitchen floor and asks me to arrange large red letters on its surface, each printed individually on waxed paper.

“Wow, Mamman, you are so brave,” I say as she irons the seventh word, Death, onto the banner while I stretch the fabric around it. “Are you really willing to die if they force us to veil?” I ask, wondering why she chose the word death instead of defiance or something like it, for death sounds too final, too scary to think about.

She sighs. “No, not really, but only because I have you, Jahan, and Afshan to worry about. I want to be around to see you all grow up. Hopefully, the ayatollah will back down.”

“But I don’t want to wear the veil, either. Can I go with you to a rally next time, just once, please?”

“No. It’s too dangerous. In the last rally, the police shot bullets up into the air to scare us,” she says, shaking her head. “I even saw a few unshaven, Islamic-looking men walking around with knives and batons.”

“Are they waiting for the ayatollah’s orders to attack?” I ask, shivering inside at the thought of Mamman standing near men who bear weapons of death.

“I think so. If he gives the orders, I won’t go anymore. You have my word.”

“Well, then, it’s safe for now. You said it yourself. That means I can go? Right?” I ask in a pleading voice.

“Okay, I’ll think about it. It’s time to go to bed,” she says, folding the banner.

We clean up the mess in the kitchen and go to bed.

The next morning, I peek through the window and watch Mamman step into a friend’s car, a black cherry Mercedes-Benz. The gold hood emblem sparkles in the sunlight as the car backs out of our driveway. Six women in disguise are on their way to have their voices heard. I’ll do just about anything to be a passenger in that car.

A week later, I’m getting ready for bed when I hear Mamman’s voice calling my name. In the kitchen, I find her sitting alone next to a large glass of steaming hot tea.

“Come here and sit down, Azadeh.” She pats the chair next to hers. “You know, tomorrow is a very special day, and I’m thinking of taking you with me to a big rally.”

“Is it special ’cause I’m going with you?” I ask, playing with my ponytail.

“No, silly. Don’t flatter yourself. Tomorrow is March 8: International Women’s Day.”

I didn’t even know such a day existed, but that is indeed a very special day. I’m a woman, or will be one soon, and based on what Mamman has been telling me, my personal freedom is at stake.

That night in my dream, I see myself standing in a large crowd of unveiled women, our fists up punching the air, shouting, “We have two choices—freedom or death—nothing more, nothing less!”

The next day, Mamman and I arrive at the rally early in the morning, our faces masked by large, dark sunglasses. Mamman meets a group of friends and begins to chatter as I unroll our banner, the same one that we made together a week earlier.

After a few minutes of examining the crowd, I ask, “Mamman, why are some women wearing chadors? Aren’t we here to protest against veiling?”

“No, we are here to protest against mandatory veiling. Most women in chadors here are like Grandma—they like to cover up but don’t want it enforced upon others like you and me. Look at that banner.” She points to two women wearing headscarves and holding up a banner a few rows behind us. It says: We are in hijab, our daughters are not. Let us be who God made us to be.

“That’s exactly right,” I say. “Let God, not the ayatollah, judge if we are sinners or not.”

“Well said, Azadeh.” Mamman and a couple of her friends applaud, making me feel proud inside.

“Azadeh, pay attention when I’m talking to you,” Mamman says firmly.

“What? Did I do something wrong?” I ask, looking around.

“I just told you not to tuck your hair behind your ears. Let it loose.”

“Why?” I ask, feeling disoriented, like a small child lost in a crowd.

“Don’t ask why. Just listen, and do what I tell you.”

I release my hair to fall over part of my face.

“That woman, over there,” Mamman points to someone in a navy-blue cloak and matching headscarf, “is taking our picture. Be aware of your surroundings.”

“Sorry, Mamman; I didn’t see her. I’ll be more careful,” I say, worrying about the picture in her camera.

A large crowd has now gathered in and around Sepah-Salar Square—a large square housing several government buildings—awaiting the speaker to take the podium in front of the parliament. From where we are, I can see a group of men and women struggling on the stage to assemble the communication apparatus for the program.

After fifteen minutes, a gentleman holding a loudspeaker comes down from the podium and says, “Many wires to our speaker system have been cut, and we are unable to continue with our scheduled program.”

The nearby crowd roars, “Death to censorship! Death to censorship!”

Moments later, groups of people begin to chant among themselves, delivering the gentleman’s message from the podium to the ends of the crowd. Within a few minutes, everyone is shouting, “Death to censorship! Death to censorship!”

Banners rise, and marching begins. “Women’s freedom is neither Eastern nor Western, but universal!”

The people in the crowd move out of the square and into Shahabad Street, shouting slogans with their fists raised and banners waving in the air. After passing several streets, we turn onto Hassanabad Street, where many nurses in white uniforms and caps appear on patios of Sina Hospital.

In solidarity, the nurses raise their fists and yell out slogans.

In return, the crowd shouts, “Salute to the nurse! Salute to the nurse!”

The nurses bow as tears stream from my eyes, Mamman’s eyes, and the eyes of most women and men striding along.

“I hope the government won’t arrest them,” one of Mamman’s friends says as we pass Sina Hospital.

I turn back to look at the nurses one last time through large, dark sunglasses, wishing that I could smash the sunglasses under my feet and tuck every strand of loose hair behind my ears to claim my identity. I’m just a coward, that’s who I am, always afraid of what may happen to me next if I do this or that. They’re so brave to take a strong stand by exposing their identities like that. God, please keep them safe.

In the middle of that night, I wake up to the glare of chandelier lights. Baba is sitting on my bed, tapping on my shoulder. “Wake up, Azadeh. Stop screaming.”

“I had a nightmare,” I say, rubbing my eyes.

“About what?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Drink some water and go back to sleep.”

“I’ll try, Baba.”

Baba kisses my forehead and turns off the light.

I bury my face under the sheet and recall my dream—tall, unshaven men beating petite nurses with batons and stabbing them with knives. I didn’t tell Baba anything, since I’m not sure if he still believes in this revolution.

Six days after the large International Women’s Day protest, the ayatollah backs off and appears on TV.

“Veiling is not obligatory but highly recommended …”

As I listen to him, I feel like a bird set free from a cage. He has no right to enforce his religious beliefs on half the population. I’m grateful to Mamman and women like her for standing up to him. Otherwise, veiling would have become the law of our land.

The post March 8, 1979: Anti-Veiling Protest in Iran appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.

March 4, 2016

Repealing of the Discriminatory Visa Wavier Bill (H. R. 158) is Gaining Momentum: How You Can Help

On December 18, 2015, the Untied States Congress passed a discriminatory visa- wavier bill, which placed unconstitutional travel restrictions upon dual-citizens of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Sudan.

On February 1, 2016, sixty-five civil rights, faith, refugee, and humanitarian organizations sent a letter to congress pointing out the discriminatory clauses of this bill. A copy of the letter, along with a full list of organizations that oppose this discriminatory bill, can be found at:

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

Professor Wade Henderson, president and CEO of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights wrote, “This pernicious restriction is shameful, xenophobic, and completely contradictory to our fundamental American values of fairness and equality. Congress has a moral and constitutional obligation to fight discrimination, and we urge lawmakers to rescind this provision by passing The Equal Protection in Travel Act immediately.”

The Equal Protection in Travel Act of 2016 (H.R. 4380) is a bipartisan effort, which was swiftly put together by lawmakers–namely Justin Amash (R-MI), John Conyers, Jr., Debbie Dingell (D-MI), and Thomas Massie (R-KY)–after the discriminatory visa-wavier bill was passed by congress in mid December of last year. Supporting The Equal Protection in Travel Act will correct the recent unconstitutional amendments that were recklessly added to the visa-wavier bill.

To support The Equal Protection in Travel Act, please sign the petition, prepared by Ali Partovi, at:

Support Equal Protection in Travel Act

Roughly 2500 individuals have signed this petition including Mark Cuban, Max Levchin, Omid Kordestani, and a long list of other successful entrepreneurs and high-tech leaders of companies such as Google, Twitter, Uber, Paypal, eBay, Zillow, Pixar, etc. See the link above for a full list of supporters and their affiliations.

Thank you.

The post Repealing of the Discriminatory Visa Wavier Bill (H. R. 158) is Gaining Momentum: How You Can Help appeared first on Azadeh Tabazadeh.