Michael Johnston's Blog, page 8

October 13, 2015

‘La Place de l’Étoile’ by Patrick Modiano

Like many other Anglophones, I only learned about Patrick Modiano last year when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature and this has prompted me to start reading his Occupation Trilogy beginning with La Place de l’Étoile, his sensational debut novel, published when the writer was only twenty-two! Critics called these first three novels dazzling and angry. This is certainly true of La Place de l’Étoile in which the improbable, but alas not impossible, protagonist is a Jewish collaborator with the occupying Germans during the Second World War.

Like many other Anglophones, I only learned about Patrick Modiano last year when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature and this has prompted me to start reading his Occupation Trilogy beginning with La Place de l’Étoile, his sensational debut novel, published when the writer was only twenty-two! Critics called these first three novels dazzling and angry. This is certainly true of La Place de l’Étoile in which the improbable, but alas not impossible, protagonist is a Jewish collaborator with the occupying Germans during the Second World War.

It is almost impossible for the British to comprehend the mind-set of an occupied nation, betrayed by its own collaborationist Vichy government and to imagine what it might have been like for many French men and woman who had to learn how to survive and to hope for eventual liberation. It took more than a generation for France to begin to accept the truths about what happened and what they, jointly and severally, did to get from one day to the next. I know from French friends of over sixty years standing, who were children during the war, how hard it has been. While active resistance was the often fatal experience for a modest number, for the rest collaboration, which ranged across the full spectrum from toleration to adulation, was a fact of life. Around the time of Les Évenements of 1968, the full story began to be told and discussed. And 1968 was when Modiano’s first novel was published.

It is in many ways a surreal novel in which the tenses and the time frame slip so that within a page the protagonist, Raphael Schlemilovitch (from the Yiddish meaning a stupid, awkward or unlucky person, or, in a looser translation ‘sonovabitch’) is at the same time battling against anti-Semitism and lauding it, a member of the Gestapo, a lover of Eva Braun and a pimp searching for women for the white slave trade. William Boyd’s introduction to the first publication of the trilogy in English sums up the first novel well. “Anti-Semitism, the Gestapo, Dreyfus, Auschwitz, Action Française, collaboration, betrayal and bad faith all contribute to the neurotic picaresque of this episodic and still startling, shocking novel.”

At first, I cast around for English-authored parallels, and certain candidates sprang to mind, but I have rejected them all. Modiano, who was born in 1945 and so has no first-hand wartime experiences, has, in his unique and distinctive way, created in fiction what is a true reflection of life, even if it does not seem that way at first reading. Serious readers of modern European literature should get stuck into this writer’s work and add him to their stockpile of literary experiences.

A word about the translation and the translator: leaden English prose would have prevented this balloon of a book from flying but the task has gone to Frank Wynne who has won several prizes for his translations from French and Spanish. I admired his work in Michel Houellebecq’s Atomised and he seems to capture the spirit of Modiano to perfection. The Occupation Trilogy, with the other two books translated by Caroline Hiller and Patricia Wolf, is published by Bloomsbury. Get yours now!

The post ‘La Place de l’Étoile’ by Patrick Modiano appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

October 6, 2015

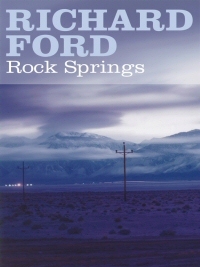

‘Rock Springs’ by Richard Ford

After making Richard Ford’s acquaintance over the past couple of years through his Frank Bascombe trilogy, which he then made a tetralogy, I have turned back to the short story collection he published in 1987. Rock Springs (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987) is set largely in the mid-western wheat growing state of Montana. Ford knows the country and his territory well. Until one reaches the Rockies in the west of Montana there is almost no geographical feature of note apart from the Missouri. The roads and the rail tracks are all but straight, especially the road north from Havre all the way to Canada.

After making Richard Ford’s acquaintance over the past couple of years through his Frank Bascombe trilogy, which he then made a tetralogy, I have turned back to the short story collection he published in 1987. Rock Springs (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987) is set largely in the mid-western wheat growing state of Montana. Ford knows the country and his territory well. Until one reaches the Rockies in the west of Montana there is almost no geographical feature of note apart from the Missouri. The roads and the rail tracks are all but straight, especially the road north from Havre all the way to Canada.

The stories reflect the scenery and how it affects the lives of the people there, especially the young people who in the post-war years, through radio, newspapers and military service, were becoming aware of an even larger world out there. There are still long-distance sleeper trains that trundle across the prairie so slowly that the events of a story spread over many hours can all take place on board. There are mile-long freight trains carrying coal or wheat. The state is a rich source of gold. There are Indians and half-Indians (now of course First Nation people) as well as the immigrant stock. The army and air force are a presence in Fort Benton and elsewhere.

Many of these elements provide the background details of stories involving hope and despair, teenage ennui and adult adultery. Whoever are the protagonists, Ford uses his acute observation, empathy and liquid prose to describe and illuminate them. This is relatively early Ford but as a writer he had already hit his stride with the first of the Bascombe books, published the previous year. For all short story readers, this book should be on their list.

Many of these elements provide the background details of stories involving hope and despair, teenage ennui and adult adultery. Whoever are the protagonists, Ford uses his acute observation, empathy and liquid prose to describe and illuminate them. This is relatively early Ford but as a writer he had already hit his stride with the first of the Bascombe books, published the previous year. For all short story readers, this book should be on their list.

The post ‘Rock Springs’ by Richard Ford appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

September 15, 2015

‘Southeaster’ by Haroldo Conti, trans. Jon Lindsay Miles

Haroldo Conti wrote Southeaster in 1962 and went on to write more novels which led to Gabriel García Márquez describing the author as one of the great Argentinian writers. Conti knew the Paraná Delta of which he writes in this book and knew the way a south-easterly wind could pile up the waters in the delta, flooding the low-lying islands. The translator, Jon Lindsay Miles has worked hard to try and convey the rhythmic pulse of the original Spanish and, working from English only, I feel he has achieved a great deal.

Haroldo Conti wrote Southeaster in 1962 and went on to write more novels which led to Gabriel García Márquez describing the author as one of the great Argentinian writers. Conti knew the Paraná Delta of which he writes in this book and knew the way a south-easterly wind could pile up the waters in the delta, flooding the low-lying islands. The translator, Jon Lindsay Miles has worked hard to try and convey the rhythmic pulse of the original Spanish and, working from English only, I feel he has achieved a great deal.

The story is of Boga, a lone sailor, fisherman and odd-job man who makes the death of his long-time reed-cutting boss, an event conveyed in powerful yet simple language, the trigger for his own ambition to become a vagabond of the delta, living mainly on and near his boat and subsisting on the fish he catches and trades for essentials. The prose evokes the flat landscapes, the minor tributaries and the man-made canals, the thick mud and the tall reeds with the water constantly ebbing and flooding, making the work of sailing, rowing and fishing just that much harder and more complicated. Conti revered Ernest Hemingway’s work and it is not surprising that several critics have drawn parallels between their writing; not least Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea and this novel, Southeaster, as evidenced by this passage.

You can’t say the river changes one way in the winter and another in the summer. The river simply changes. The islands, on the other hand, seem different each season. Not just for the striking green of summer, but far more subtle things. In winter, from the open sea, they vanish in a distant mist. They’re there, and then they’re not. You come to doubt the river and believe you’ll never reach them, despite the faint uneasiness that cuts you off and rocks you and in a way distresses you. These shores may prove illusory, a shadow out towards the west, swayed by the horizon. And if at last you draw near, they come to seem remoter still, colonised by loneliness, by silence and a sadness past repair.

Being less than twenty miles from Argentina’s capital, the town of Tigre and the wide Paraná delta beyond are, nowadays, a major tourist attraction with excursion boats as well as canal barges, luxury hotels as well as rowing and sailing clubs extending many miles up the river. But, in the time of which Conti writes, these developments were well into the future and the economy was not flourishing. Tigre was an industrial town.

Conti deserves to be better known, beyond those who specialise in Latin American literature and, once more, the enterprising publisher & Other Stories deserves credit for bringing us this book. Alas, they cannot bring us Conti. He was one of the thousands of victims of Argentina’s Dirty War, being numbered among the ‘disappeared’, arrested in his apartment in 1976 and never seen again.

This book is one to be read at a leisurely pace, being carried along by the prose just as Boga’s boat is carried along by the waters of the delta. Highly recommended.

The post ‘Southeaster’ by Haroldo Conti, trans. Jon Lindsay Miles appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

September 7, 2015

‘Athena’ by John Banville

John Banville certainly pulls it off for me in Athena (London: Minerva, 1996) with his tale in the form of a love letter, told by an introspective loser with a past that burdens him and little expectations of the future; a tale of art theft, forgery, fraud and lust (you can see why it appeals to me) played out against the background of late 20th century Dublin. The narrator tells us very early on that his name, Morrow, is his new alias and as the tale unfolds we pick up the subtle hints of a past he would like to shrug off and, if only he could, forget. He has used his ‘past’ to become an expert in Art History, especially the 17th century, and this, he thinks, is why he has been pulled in by a ‘developer’ to appraise and authenticate a group of paintings. That just such a group of paintings has been recently stolen from a private collection is something we become aware of.

John Banville certainly pulls it off for me in Athena (London: Minerva, 1996) with his tale in the form of a love letter, told by an introspective loser with a past that burdens him and little expectations of the future; a tale of art theft, forgery, fraud and lust (you can see why it appeals to me) played out against the background of late 20th century Dublin. The narrator tells us very early on that his name, Morrow, is his new alias and as the tale unfolds we pick up the subtle hints of a past he would like to shrug off and, if only he could, forget. He has used his ‘past’ to become an expert in Art History, especially the 17th century, and this, he thinks, is why he has been pulled in by a ‘developer’ to appraise and authenticate a group of paintings. That just such a group of paintings has been recently stolen from a private collection is something we become aware of.

Other fascinating Dublin characters, worthy of Joyce, populate the pages. The cross-dressing Da, master villain, Inspector Hackett who pursues the several villains, Aunt Corky, his rich, widowed elderly relative, and A (for A read Athena) who crosses Morrow’s path and swiftly becomes his lover. So, as if the complex story were not enough, punctuated by short but detailed descriptions of each of the paintings in the style of Gombrich, we have the added and wonderful element of Banville’s superlative craftsmanship with language which eddies and swirls across the pages, carrying the reader effortlessly along. The Sunday Times said of the book, ‘sleek, beautiful, breathtakingly cunning prose.’

Athena is a love letter to Morrow’s long-term passion for Art and his immediate and overwhelming passion for A. The plot twists and turn like a detective story and the only early clue that things might not turn out too badly is the information at the outset that Aunt Corky has left him all her money. Only a hint of Banville’s lovely language, his simple yet satisfying similes and his writer’s eye for the perfectly positioned phrase that draws the eye, the mind and the reader’s appreciation, is possible in this brief review.

With dusk comes rain that seems no more than an agglutination of the darkening air, drifting aslant in the lamplight like something about to be remembered. … I squirm like a slug in salt. … fighting my arms into my mackintosh as if it were a pair of recalcitrantly flaccid wings I was trying to put on. … The rain on the window whispered to itself, agog to know what we would do next. … The front door as I approached it across the hall had a pent-up, gloating aspect, as if it were dying to fly open and unleash on me a shouting throng of accusers.

Banville frequently creates the persona of a middle-aged man coping with loss, as in his Booker Prize winning The Sea and again in his recently published new novel The Blue Guitar which I have just added to my long, long reading list! Maybe I hanker to be middle-aged again, but, on reflection, maybe I don’t.

The post ‘Athena’ by John Banville appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

August 3, 2015

‘Indignation’ by Philip Roth

My enthusiasm for the storytelling prose of Philip Roth has only been increased by reading Indignation (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008).

My enthusiasm for the storytelling prose of Philip Roth has only been increased by reading Indignation (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008).

As it begins, the story of young Marcus Messner, son of a kosher butcher in Newark NJ, is archetypal Roth. A young Jewish protagonist exploring the boundaries of his life and propelled by a desire for intercourse before he dies. His father has begun arguing with him all the time and saying that unless Marcus does what he tells him then he will land in the deepest trouble in the world out there. Such have been the rows that Marcus has quit Robert Treat college in Newark where some of the exciting teachers came out from New York to stir his imagination and moved to Winesburg, a Mid-Western liberal arts college in north-central Ohio, fifteen miles from Lake Erie where there are only a handful of Jews. All he wants is to get straight As and graduate so that, if he were to be drafted to fight in the war then raging on the Korean peninsula, he would do so as a junior officer rather than a private. This, he reckons, would enhance his chances of surviving.

The account of his difficulties at Winesburg is interspersed with his back story as a willing helper in his father’s butcher’s shop as a growing boy. He quarrels with his roommates and changes dormitories. Then he plucks up courage to date a gorgeous blonde Gentile who allows him, and who takes, such physical liberties that he is totally smitten. The solicitous Dean of Men enquires whether he has a problem with relationships after those quarrels with his fellow students. There is a gloriously scripted row with the Dean which suddenly ends when Marcus throws up on the Dean’s carpet. It turns out he has appendicitis and, post-operation, he is visited in hospital by his femme fatale and, not long after, by his mother who makes him promise to give her up. Then tumultuous events that follow a heavy, Mid-Western snow storm make all that has gone before rather irrelevant.

However, on the way to that point in the story, Roth has slipped in a cryptic piece of information on page 54 that completely alters the reader’s perspective on the novel. With this blog’s strict no-spoiler rule, I cannot even hint what that is but the rest of the book charts the inevitable decline and fall of Marcus Messner. Indignation has all the characteristics of a ‘Jewish’ Greek tragedy.

By opening a window onto the several different Americas that, to this day, co-exist within the United States; by presenting the attitudes that prevailed during the early 1950s and the Korean War; and by painting a lucid account of one young man’s growing up pains, Roth has written a valuable social document as well as an immensely readable novel.

The post ‘Indignation’ by Philip Roth appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

July 23, 2015

‘Now and at the hour of our death’ by Susana Moreira Marques

This is Moriera Marques’s first book; a slim volume with not a syllable wasted (London: & Other Stories, 2015. Translated by Julia Sanchez). Now and at the hour of our death comes from this award-winning journalist’s visits, over a period of five months in 2011, to northern Portugal, to an out of the way part of an already remote region known as Trás-os-Montes; in other words, over the hills and far away. She went there to observe the work of a team of healthcare professionals as they worked to bring palliative care to dying patients in that otherwise forgotten part of the country. The aim of the team was to help their patients live out the end of their lives in as much comfort and with as much dignity as possible; dying in company and at home.

This is Moriera Marques’s first book; a slim volume with not a syllable wasted (London: & Other Stories, 2015. Translated by Julia Sanchez). Now and at the hour of our death comes from this award-winning journalist’s visits, over a period of five months in 2011, to northern Portugal, to an out of the way part of an already remote region known as Trás-os-Montes; in other words, over the hills and far away. She went there to observe the work of a team of healthcare professionals as they worked to bring palliative care to dying patients in that otherwise forgotten part of the country. The aim of the team was to help their patients live out the end of their lives in as much comfort and with as much dignity as possible; dying in company and at home.

Apart from the human stories from people of varying ages and circumstances in these villages, the lyrical prose, the variety of dramatic unfolding of the stories, and the obvious empathy of the writer combine to bring the reader very close to each individual and their families, coping with the inevitable. They are coping too with rural depopulation, as the younger Trasmontanos leave for towns, cities and to go abroad. Some have gone to what was Portuguese Angola but been driven from there by the independence civil wars and have had to come back to their home villages to die.

The quality of the language owes much to the talented translator, Brazilian-born Julia Sanches, who does that relatively rare thing of translating out of her mother tongue into her learned language of English.

It’s good to read a little non-fiction as an antidote to the escapism engendered by fiction. The enterprising publisher, & Other Stories, who bring Anglophones many excellent books of fiction from other parts of the world, has done us all a favour with this poetic factual account of a universal problem.

The post ‘Now and at the hour of our death’ by Susana Moreira Marques appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

July 14, 2015

‘How to be both’ by Ali Smith

Garlanded with prizes and short listings, Ali Smith’s latest novel How to be both (London: Penguin, 2015) is one to savour. Smith tells two stories that co-exist within the cover of the book and are coeval as narratives despite, at first sight, being set six centuries apart. But that should be no problem for a novelist; certainly not a novelist of Ali Smith’s capabilities. Her stories are meant to complement each other and, sure enough, the sum of the parts becomes greater than the whole.

Garlanded with prizes and short listings, Ali Smith’s latest novel How to be both (London: Penguin, 2015) is one to savour. Smith tells two stories that co-exist within the cover of the book and are coeval as narratives despite, at first sight, being set six centuries apart. But that should be no problem for a novelist; certainly not a novelist of Ali Smith’s capabilities. Her stories are meant to complement each other and, sure enough, the sum of the parts becomes greater than the whole.

Between the two stories there are parallels: motherless young protagonists, George and Francesco, introspective and coming to know and understand themselves; a love of artistic expression; and a need to overcome life’s inevitable injustices.

The difference in the two narrative voices adds light and shade to the texture. The voice of the 21st century is that of a teenager still vividly recalling a lost mother and still talking with her, as only a precocious, tech-savvy teenager can these days. The late mother had a passions for a particular Italian artist part of whose work is reproduced on the inside front and back covers of the book. The narrative is simultaneously in both past and present. The contrasts and contradictions are perfectly caught and ring so very true.

The young 15th century artist has a different voice that describes the trials and travails of a painter of frescoes, a hired brush available to decorate the ducal walls of Ferrara and other Renaissance Italian cities. The artist too has a secret which some guess intuitively and which is slowly revealed to the reader. The artist is also long dead, which is not surprising given the lapse of time and the many more hazards to life in the 15th century. Even so, in a magically realist way, Ali Smith brings the painter to life after death.

The reader involvement and satisfaction is multiplied by the parallels and contrasts between the two narrators. That satisfaction is heightened by Smith’s use of stimulating language and the styles of the two narratives; perfectly chosen.

Since several dozen eminent critics called it their book of the year in 2014, I expected great things and, right through the book, I found them.

The post ‘How to be both’ by Ali Smith appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

June 26, 2015

‘The Story of the Night’ by Colm Tóibín

It is with great pleasure that I can report that The Story of the Night (London: Picador, 1997), Colm Tóibín’s third novel has completely blown away the clouds that had gathered after I blogged about my feeling of mild disappointment after reading his latest, Nora Webster. For reasons set out below, it also had a special resonance for me; not the more obvious one.

It is with great pleasure that I can report that The Story of the Night (London: Picador, 1997), Colm Tóibín’s third novel has completely blown away the clouds that had gathered after I blogged about my feeling of mild disappointment after reading his latest, Nora Webster. For reasons set out below, it also had a special resonance for me; not the more obvious one.

Richard Garay, son of an English mother and a long-deceased Argentinian father, grows up in Buenos Aires. Although fluent in both parental languages, he saw himself as Argentinian and knew himself to be gay; something he had not yet shared with his mother. Garay’s story begins around the time his mother dies.

During the last year my mother grew obsessive about the emblems of empire: the Union Jack, the Tower of London, the Queen and Mrs Thatcher. As the light in her eyes began to fade, she plastered the apartment with tourist posters of Buckingham Palace and the changing of the guard and magazine photographs of the royal family; her accent became posher and her face took on the guise of an elderly duchess who had suffered a long exile. She was lonely and sad and distant as the end came close.

[…]

She died before the war and thus I was spared her mad patriotism and foolishness. I know she would have waved a Union Jack out of the window, that she would have shouted slogans at whoever would listen, that she would have been overjoyed at the prospect of a flotilla coming down from England, all the way across the world in the name of righteousness and civilization, to expel the barbarians from the Falkland Islands.

And, of course, I am hooked already, for a variety of reasons, starting with the fact that in 1957 I sailed in the British aircraft carrier HMS Warrior from Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands directly to Puerto Belgrano where she moored just astern of the General Belgrano, later to become better known at the time of the Falklands war. As one of the ship’s officers, I met Admiral Rojas whose flagship it was and who, when he died, asked for his ashes to be scattered over the sea where the Belgrano went down.

While Garay’s mother might seem a mildly eccentric figure of fun, the novel is a poignant account of the coming of age and the eventual ‘coming out’ of the narrator. He recounts his story in the earlier chapters against a background of the invasion of Las Malvinas and the confidence-shattering defeat of the poor conscripts in the Argentine army despite the heroics and bravery of their air force. It was the time of the Generals and of the Disappeared when it was better not to get involved in any political discussions. In the aftermath, under the Menem presidency, Argentina clawed its way back to American-encouraged capitalism and privatization, and Richard discovered his own sexuality and met the man he would love for the rest of his life.

But remember! This is the 1980s and the gay community was beginning to take the full impact of HIV/AIDS; all of which means that a book that starts off seeming to be light-hearted, moves, page by page, into darker territory. Colm Tóibín handles the transition with style and fluency.

Given that this blog likes to avoid any suggestion of plot spoilers, there is little else that needs to be said other than that I, and I hope you, will soon be reading more Tóibín.

The post ‘The Story of the Night’ by Colm Tóibín appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

June 8, 2015

‘Chronicle of a Death Foretold’ by Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez, who died last year, knew how to grab your attention from the very first sentence, as in his Chronicle of a Death Foretold (London: Penguin, 2007).

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez, who died last year, knew how to grab your attention from the very first sentence, as in his Chronicle of a Death Foretold (London: Penguin, 2007).

On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on.

García Márquez based his novel on an actual murder that took place at the beginning of the 1950s and the character of the victim is drawn on an old friend of the author but I still have to find out if that friend was actually murdered. There is always something more to learn after reading any of García Márquez’s novels. The story breaches the usual convention of beginning at the beginning but, instead, unfolds the story in reverse, exploring the labyrinthine back story that led to the Vicario brothers killing Santiago Nasar. In each succeeding chapter, not only is a different facet of the story revealed but one reads how, so easily, the death, once it had been foretold, could have been forestalled.

García Márquez is to Latin America what Faulkner is to the Southern states of the USA. Their prose has all the authentic flavours of the region. The former much admired the latter. There are parallels that could be drawn between the two writers but each, it must be stressed is a unique and wonderful writer. Perhaps there is a little more self-deprecating humour in García Márquez’s narrator, who, we learn, has been seeking to compile this chronicle. The focus of the night before the death had been the fabulous wedding celebrations of the groom, Bayardo San Román, to the beautiful Angela Vicario. The marriage lasted around five hours before Bayardo brought her back to her parents’ house and left the town.

The story tells of the reactions of a wide cast of characters both to the news of the intention to kill, widely disbelieved, and the news of the actual killing, and then the whole train of consequences. What is not foretold (nor will I reveal it) is the fascinatingly surprising dénouement which could be a whole new story on its own.

Read García Márquez for the near continuous perfection of his dramatic prose and, after this one, go on over time to his complete works.

I have only one complaint. I have noticed before that the American publisher Alfred A Knopf buys the copyright in the translations he commissions which is fine as far as it goes but in the edition I have just read the translator’s name is nowhere mentioned and that is unforgivable. Those in the know are aware it was one of two people: Gregory Rabassa or Edith Grossman (in this case Rabassa); and readers of his work in English ought to know and respect them.

The post ‘Chronicle of a Death Foretold’ by Gabriel García Márquez appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

May 29, 2015

Does ‘Nora Webster’ succeed for Colm Tóibín?

Nora Webster (London: Penguin, 2015) has been highly praised and shortlisted for literary prizes. Colm Tóibín is a highly regarded Irish novelist whose other work, The Master held me in thrall, moving with all the subtle slowness of Henry James, the master of the title. At the end of reading Nora Webster I am, I confess, disappointed.

Nora Webster (London: Penguin, 2015) has been highly praised and shortlisted for literary prizes. Colm Tóibín is a highly regarded Irish novelist whose other work, The Master held me in thrall, moving with all the subtle slowness of Henry James, the master of the title. At the end of reading Nora Webster I am, I confess, disappointed.

There is clearly a powerful human story in observing that period of a woman’s life after she has been widowed much too soon. Nora’s daughters are in their late teens and have more or less flown the nest but her two sons, Donal with the stammer that has developed after his father’s death and Conor, observant and intelligent beyond his years, are not yet out of primary school. Nora has to contend with all the problems and without sufficient means. This is the account, closely observed, of how she battles to recover her own individual identity, not just Mrs Webster, Maurice’s wife, but a woman with her own feelings and an inner determination to overcome her loss and to live again.

She has to cope with returning to work in the office she left to get married and where now her embittered school friend, nicknamed ‘The Sacred Heart’, rules the roost by keeping as much as possible secret and by terrorising her staff. Her boys were clearly traumatised by being left with their great-aunt while their father was in hospital dying, and are wary now of being excluded again. Their problems run through the story.

Tóibín recounts Nora’s story which is played out in the late 1960s against the civil rights troubles in the north and the deeply conventional Catholicism of the south. Tóibín’s every turn of phrase captures the very Irishness of the story acutely and reminds the reader of the often neglected southern Irish perspective. In that regard, the book is excellent. Nora’s battles and her several victories have the reader backing her all the way. Her rediscovery of music and singing as both therapies for her soul and a new focus for her single life run like two continuous threads through the story. And yet …

I found the various dramas at work, at home and in her social life were too fragmentary and they did not engage my enthusiasm as I had hoped and expected. However, I am resolved to read at least one more Tóibín novel to see whether this one is just an exception and the enjoyment I had from The Master is repeated in his other work.

The post Does ‘Nora Webster’ succeed for Colm Tóibín? appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

Michael Johnston's Blog

- Michael Johnston's profile

- 4 followers