Michael Johnston's Blog, page 7

January 20, 2016

‘The Penguin Lessons’ by Tom Michell

What a joy to read is The Penguin Lessons [London: Michael Joseph Penguin, 2015] by Tom Michell! For me in particular, there are associations and coincidences that make it an even more fascinating read since, in several ways, our paths have crossed.

What a joy to read is The Penguin Lessons [London: Michael Joseph Penguin, 2015] by Tom Michell! For me in particular, there are associations and coincidences that make it an even more fascinating read since, in several ways, our paths have crossed.

As a young man in his early twenties Tom Michell was seeking adventure as well as a job and successfully applied for the post as Assistant Master at a swanky public school at Quilmes on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. This was in the 1970s, the dying days of the Peronist regime that was soon to be ousted by the military, for the second time. Life was full of fascinating coincidences for Tom who was on holiday in the Uruguayan resort of Punta del Este, house sitting for friends, when on his evening stroll on the day before his return to work in Argentina he spotted a raft of dead and dying penguins covered in oil and washed up on the beach – but one of them had survived. His rash decision to rescue that survivor which, to begin with, tried to fight him all the way, is the prologue to an enchanting story of the bonding of the man, Tom, and the Magellanic penguin, Juan Salvador Pingüino.

In the short time he had left that night before catching his bus to Montevideo and the ascafo up the Rio de la Plata to Buenos Aires, he managed to clean and calm the bird, so much so that he was able to get as far as the Argentine customs before he was stopped. How he dealt with that problem you must read for yourself. However, there wouldn’t be a story if he hadn’t surmounted not only that problem and many others. You will find out how the penguin made itself at home a St George’s School and became the rugby team’s mascot; which fascinated me, since, in 1957, as a young naval officer, I was invited to Quilmes to talk to the prep school about my ship which had just sailed directly from the Falkland Islands to the Argentine and, at one point, secured astern of the ARA General Belgrano; not something that has been done since. The passionate feelings of many Argentinians about Las Malvinas is flagged up.

Later in the story, Michell makes an expedition by train and motorbike to Valdés in the south of the country where there is still a breeding colony of penguins to investigate the possibility of taking Juan Salvador there and liberating him. His adventures show how resourceful and lucky he was. However, the key moment of drama in the whole story is the quite profound and life-changing effect Juan Salvador had on one particular boy.

The tremendous quality of the writing is what lifts a simple recollection into a philosophical memoir that is well worth rereading. What a boon for its publisher: who happen to be Michael Joseph Penguin!

The post ‘The Penguin Lessons’ by Tom Michell appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

January 13, 2016

‘The President’s Hat’ by Antoine Laurain

The President’s Hat [London: Gallic Books, 2013] by Antoine Laurain more or less jumped off the shelf and sat on my head until I had read it. Readers will remember my enthusiastic review of a later novel by Laurain, The Red Notebook and I think this one is just as good. I didn’t think so at first. I thought it was going to be like those English compositions we had to write in primary school such as ‘The Adventures of a Penny’ where it goes from hand to hand. However, very soon it becomes obvious that this is a witty and well-written novel in which a black Homburg belonging to France’s President, François Mitterand, is mislaid and then appropriated, one after another, by different characters. For each, it becomes an impulse to major changes in their lives. The story is brought to a fascinating and convincing dénouement.

The President’s Hat [London: Gallic Books, 2013] by Antoine Laurain more or less jumped off the shelf and sat on my head until I had read it. Readers will remember my enthusiastic review of a later novel by Laurain, The Red Notebook and I think this one is just as good. I didn’t think so at first. I thought it was going to be like those English compositions we had to write in primary school such as ‘The Adventures of a Penny’ where it goes from hand to hand. However, very soon it becomes obvious that this is a witty and well-written novel in which a black Homburg belonging to France’s President, François Mitterand, is mislaid and then appropriated, one after another, by different characters. For each, it becomes an impulse to major changes in their lives. The story is brought to a fascinating and convincing dénouement.

No more can not be revealed but I can say that Laurain has written now six novels, the latest due out this year. I had only one beef and that is with the UK publisher Gallic Books. Why was, or so it seemed to me, the excellent translator not named in either of the books they have published? I have no problem with them owning the copyright provided they have paid market rates to the translator but the profession of translation depends on the translator becoming known. Gallic Books have explained to me that the translators, mentioned at the back of the book as having ‘voiced’ the different characters, are Louise Rogers Lalaurie, Emily Boyce and Jane Aitken. The translators of The Red Notebook were Emily Boyce and Jane Aitken, as listed in the prelims on pages one and five. It is an interesting concept to use different translators for different narrators and, in these two cases, it does seem to have worked well. The publisher’s own website gives full details of all the translators they use so I am more than pleased.

The post ‘The President’s Hat’ by Antoine Laurain appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

January 7, 2016

‘Revelation’ by C J Sansom

Revelation [London: Macmillan, 2008] is a revelation: Sansom’s fourth novel in his Shardlake series of Tudor detective thrillers was my eye-opener to the series in which Matthew Shardlake, a lawyer in mid-16th century London, battles through blood, poisoning, stabbing, flame and explosion to solve the mystery of who is the perpetrator of a series of horrendous murders. Crime novel readers could hardly ask for more. The pressure and tension are never lifted and seem to grow with each succeeding chapter.

Revelation [London: Macmillan, 2008] is a revelation: Sansom’s fourth novel in his Shardlake series of Tudor detective thrillers was my eye-opener to the series in which Matthew Shardlake, a lawyer in mid-16th century London, battles through blood, poisoning, stabbing, flame and explosion to solve the mystery of who is the perpetrator of a series of horrendous murders. Crime novel readers could hardly ask for more. The pressure and tension are never lifted and seem to grow with each succeeding chapter.

This was my first Sansom novel which I was prompted to read since I had become tired of waiting for more from Hilary Mantel! Not that the two writers, in terms of style, approach and intent, have anything more in common than a focus on that period in Tudor life when Henry VIII decided to go to any necessary lengths to secure his divorce from his first wife, seize the assets of the Church in England and then work his way through the list – divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded – until he seeks his sixth wife who managed to survive him. This the moment in time when Revelation is set.

Shardlake narrates and sets the scene. It is Tudor London in 1543 and, thanks to services rendered in the past, as set out in the earlier novels of the series, he is an advocate at the Court of Requests which handles cases of litigants who do not have the resources to plead. However:

It was true that London was full of both beggars and fanatics now, an unhappy city. And a purge would make things worse, there was, too, something I had not told the company; the parents of the boy in Bedlam were members of a radical Protestant congregation, and their son’s mental problems were religious in nature. I wished I had not taken the case, but I was obliged to deal with the Request cases that were allocated to me. And his parents wanted their son released.

Sansom has the knowledge and the gift to describe graphically the sights, sounds and smells of the city which is the location for his story. Very soon, his close friend and fellow lawyer, Roger Elliard, is brutally murdered and his body placed in a fountain in Lincoln’s Inn. Shardlake vows to Roger’s widow that he will find her husband’s killer. He is summoned to a meeting with Archbishop Cranmer where he learns that there has already been a similar brutal killing, possibly even two killings. With the King’s Assistant Coroner, he is charged by Cranmer to solve the cases and find the killer. For political reasons, however, it must be a secret inquiry.

The intense and internecine battle between those whose preference would be to drift back to the ‘old’ religion, Catholicism, and those who want to achieve a completely Protestant church and nation colours the whole narrative. Fear of the consequences of being on the ‘wrong’ side in these intolerant times permeates the minds of everyone involved. After all, these consequences could include being burned alive.

Shardlake’s investigations uncover the possible motivation for the serial killer’s actions and a hint of his future targets. You will need to read Revelation to find all revealed in a way that grips the reader to the very last chapter. As my blogs eschew plot spoilers, that is all I can say here but I have bought the first in the series Dissolution to see how it all began. Readers new to Sansom can, of course, read any one of the six Shardlake books in any order but will probably gain from starting at the beginning.

The post ‘Revelation’ by C J Sansom appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

December 30, 2015

‘Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs’ by Lina Wolff, trans. Frank Perry

Swedish writer Lina Wolff has both lived and worked in Italy and Spain, experience she has put to use in her first novel, Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs [High Wycombe: & Other Stories, 2016]. An eye-catching title is never a disadvantage and this one does have its origin in the text but you would never guess it until you come across the reference. Wolff’s novel is cleverly constructed and conspicuously well written; aided in the English version by the excellent translation by Frank Perry.

Swedish writer Lina Wolff has both lived and worked in Italy and Spain, experience she has put to use in her first novel, Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs [High Wycombe: & Other Stories, 2016]. An eye-catching title is never a disadvantage and this one does have its origin in the text but you would never guess it until you come across the reference. Wolff’s novel is cleverly constructed and conspicuously well written; aided in the English version by the excellent translation by Frank Perry.

The novel’s narrator, Araceli, is a young Catalan girl, living in Barcelona, but the author uses several devices to expand the number of voices. Other protagonists talk to her and, at one point, there is a short story ‘written’ by Alba Cambó, an eccentric writer around whom the narrative circles. Araceli has read several of Alba Cambó’s short stories in the fictional magazine Semejanzas (Similarities) and, as the book begins, she is living with her mother in the apartment above the one shared by Cambó and her black companion, Blosom. However, Alba persuades her mother to let Blosom move upstairs to make space for Alba’s latest conquest, Valentino. Valentino makes himself useful including driving Araceli to school, which is how the book opens.

‘It was Friday two weeks ago,’ Valentino told me on one of the days he drove me to school. ‘Alba Cambó and I met up at ten that morning and went for a spin in the car. They were playing Vivaldi on the radio. I had pushed the top back and it was a lovely day, the kind of day when the air smells of figs, salt water and sweet exhaust fumes. Alba was sitting in the same place as you are now, her head against the neck-rest, looking up at the roofs as we drove through the streets and avenues, I recognised the music they were playing on the radio and hummed along to it while driving. I could never make love to Vivaldi, Alba said at that point. Vivaldi’s beautiful, don’t you think, I said. That’s why, she said. Imagine making love to the Gloria. Only a saint can do that, and saints aren’t supposed to make love.

Alba has other lovers, such as Ilich and Rodrigo Auscias, whose paths cross and the latter relates his experiences to Araceli in an extended section that takes him a whole night. It is in this passage that we realise where the book’s title comes from. Interwoven with the accounts of others, Araceli tells her own story. This makes the book a series of episodes with an interlinking narrative and the whole hangs together in a very satisfying and highly readable text.

It would be hard to say more without revealing the subtle plot of the novel, so suffice to say that this last book of my reading year merits an 8.5 out of 10 rating and encourages me to look forward to Wolff’s next novel, due out in Sweden in 2016, De polyglotta älskarna, which Frank Perry might translate as The Polyglot Lovers. I hope he is working on it already.

The post ‘Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs’ by Lina Wolff, trans. Frank Perry appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

December 21, 2015

‘Martin John’ by Anakana Schofield

This is Anakana Scofield’s second novel. I seemed to have missed her first, Mularky. Martin John [High Wycombe: & Other Stories, 2016] is an artistic and intellectual tour de force. In the tradition of writers who can project themselves into the mind, mannerisms and minefield of seeing the world from an altogether different and damaged perspective (for example, Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, and Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time) Schofield creates a character whom we might well cross the street to avoid but who, even so, deserves our compassion.

This is Anakana Scofield’s second novel. I seemed to have missed her first, Mularky. Martin John [High Wycombe: & Other Stories, 2016] is an artistic and intellectual tour de force. In the tradition of writers who can project themselves into the mind, mannerisms and minefield of seeing the world from an altogether different and damaged perspective (for example, Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, and Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time) Schofield creates a character whom we might well cross the street to avoid but who, even so, deserves our compassion.

My tutor would have called her style post-modern but the material and the message is in the here and now. Having transgressed in his Irish hometown, Martin John is packed off to London by his mother, at a loss to know how to cope with his behaviour. It might have momentarily have eased her problem but it simply means that Martin John continues his obsessive-compulsive and anti-social behaviour elsewhere. We see too how difficult it is for a fragmented, inadequately funded and endemically poor-to-communicate social care sector to cope with problem behaviour like Martin John’s.

Martin John is convinced that his unofficial lodger, Baldy Conscience, is out to get him and that everyone else is in league with Baldy; perhaps even his own mother.

Mam said I can’t save you.

She never said the truth. The truth is THEY ARE COMING FOR HIM. How long has she known about Baldy Conscience?

Did she maybe send him? Have they met?

Did they meet at Euston?

Was it mam who told him to go do the circuits at Euston?

No. No. That’s not it. She said keep the head down. She said she didn’t want him on the Tube. She said Keep the head down, Into bed at night, Don’t mind anybody and they won’t be minding you either. She said other things. He cannot remember the other things. Did she warn him about Baldy Conscience? How did she know about Beirut?

He is confused. Painfully confused. He must walk. He must settle this question of what mam knows.

The book is built from short, sometimes very short, blocks of text. The text repeats and restates Martin John’s problems exactly as one imagines they occur to him. It also conveys his mother’s despairs and exasperations. It brings home the obsessive-compulsive mind-set of Martin John. How can one convince a sociopath that we are not all out to get him since some of us so obviously are? In this respect alone, Schofield’s book is a ‘must read’. We shall hear more from this English-born Irish-Canadian author and we are indebted to & Other Stories for publishing this book.

The post ‘Martin John’ by Anakana Schofield appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

December 14, 2015

‘The Conquest of Plassans’ by Émile Zola; trans. Helen Constantine

Visiting Lyon for a week, I took with me The Conquest of Plassans by Émile Zola [Oxford: OUP, 2014]; a good choice as it turned out. Never short of ambition and seemingly able to write to a band playing, Émile Zola completed this fourth volume of the twenty book Rougon-Macquart novels in 1874. The two connected but opposing families have their roles in this volume. The two central characters are Marthe, a Rougon, and the Abbé Faujas, a zealous and, it seems, cunning supporter of the Imperialist government after the coup d’état. Marthe’s husband, François Mouret is a semi-retired businessman who does not consult his family about important decisions which is why, in the first chapter, Marthe finds out that he has rented their rather decrepit second floor to a newly arriving priest and his mother. The Mourets are not practising Catholics although one of their sons seems to have chosen the priesthood. Marthe is unhappy with the prospect of any strangers, not least such strangers in her house. The story unfolds as the Abbé gradually takes over the house, the local church hierarchy, the town and, finally, Marthe herself as he sets out to conquer the too republican Plassans as a covert agent for the government in Paris.

Visiting Lyon for a week, I took with me The Conquest of Plassans by Émile Zola [Oxford: OUP, 2014]; a good choice as it turned out. Never short of ambition and seemingly able to write to a band playing, Émile Zola completed this fourth volume of the twenty book Rougon-Macquart novels in 1874. The two connected but opposing families have their roles in this volume. The two central characters are Marthe, a Rougon, and the Abbé Faujas, a zealous and, it seems, cunning supporter of the Imperialist government after the coup d’état. Marthe’s husband, François Mouret is a semi-retired businessman who does not consult his family about important decisions which is why, in the first chapter, Marthe finds out that he has rented their rather decrepit second floor to a newly arriving priest and his mother. The Mourets are not practising Catholics although one of their sons seems to have chosen the priesthood. Marthe is unhappy with the prospect of any strangers, not least such strangers in her house. The story unfolds as the Abbé gradually takes over the house, the local church hierarchy, the town and, finally, Marthe herself as he sets out to conquer the too republican Plassans as a covert agent for the government in Paris.

From the point of view of the Mouret family, the story goes from bad to worse. Faujas has seedy relatives who join him upstairs, greedy and rapacious. The Abbé schemes and accomplishes his successive goals while poor François is literally driven out of his mind and into the local asylum as Marthe becomes devoted to the church and a disciple of Faujas. The Mouret family members are, one by one, driven from their home. All this is set against a backdrop of back-biting and intrigue concerning local rivalries, Rougon versus Macquart feuding, and national politics. Familiar motives like greed, envy and self-indulgence play the roles they seem to play not only in Zola’s novels but in life writ large.

For what it’s worth, since this blog does not reveal plots, the Abbé gets his come-uppance, as do the other villains of this complex piece but, as is so often the case in Zola, the good seldom get their just reward; not in this world anyway.

For those new to Zola, try out two novels first: Germinal and The Ladies’ Paradise and if they take your fancy that leaves only eighteen others to read over the next few years. As it says of favoured restaurants in the Guide Michelin, ça vaut le détour. Zola can be compared and contrasted with Dickens as a powerfully observant chronicler of his century but bear always in mind that as the author himself said, ‘the real in literature cannot be the real in nature’ and that the work of art is ‘a corner of nature seen through a temperament’. I lifted these last two observations from the excellent introduction by Patrick McGuiness and I also commend the lively new translation by Helen Constantine.

The post ‘The Conquest of Plassans’ by Émile Zola; trans. Helen Constantine appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

December 7, 2015

‘Number 11’, or ‘Tales that Witness Madness’ by Jonathan Coe

Twenty-five years on, Jonathan Coe has written a fascinating sequel to his satire of the nineteen-eighties. Number 11 [London: Viking, 2015] in which he now sends up the early years of this century. Coe is a talented novelist with a gift for pointing up the absurdity and selfishness of a certain type of person; in simple terms the haves, at the expense of the have nots. He is also a master of his craft as a novelist.

Twenty-five years on, Jonathan Coe has written a fascinating sequel to his satire of the nineteen-eighties. Number 11 [London: Viking, 2015] in which he now sends up the early years of this century. Coe is a talented novelist with a gift for pointing up the absurdity and selfishness of a certain type of person; in simple terms the haves, at the expense of the have nots. He is also a master of his craft as a novelist.

The novel begins and (almost) ends with Rachel visiting her grandparents’ house in Beverley. The events in between interweave Rachel and her friends and acquaintances as they encounter and usually come off worst against the next generation of the Winshaw family and its hangers-on. It has to be the next generation since Coe killed off all of the previous generation in one gory night back in 1991. However, their spirit lives on.

Coe’s political heart is on the left, further left than some but with a tolerance for those to the right of him. Whereas What a Carve Up! is an out-and-out rollicking satire that provides great and often very funny entertainment, this apparent successor novel, written a quarter of a century later by a more mature author, has greater depth and subtlety. The five different set pieces portray various aspects of austerity Britain and give the lie to the humbug that we are all in this together. To the extent that time travel is not yet possible, Osborne may be right; but that we are all sharing a proportionate amount of the burden was never less true. Having got that off my own chest, and not being able to reveal too much (my one rule of these reviews) I suggest that one ought to re-read What a Carve Up! and then tackle Number 11 which was nearly subtitled What a Whopper!. Both that fairly forgettable film and this new novel end with a big surprise. Coe’s surprise lifts the book even further in my estimation and puts it in contention for the next Man Booker, if it is time for a humorous novel to win again; which doesn’t happen often enough.

The post ‘Number 11’, or ‘Tales that Witness Madness’ by Jonathan Coe appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 30, 2015

‘The Blue Guitar’ by John Banville

John Banville’s latest novel, his fifteenth, is up there with the best. The Blue Guitar [London: Viking, 2015] is the confessional monologue of a lapsed artist, chronic petty thief, occasional adulterer, runner-away from troubles and product of his somewhat chaotic life. That narrator, Oliver Orme, talks almost as well as John Banville writes and that is a serious compliment.

John Banville’s latest novel, his fifteenth, is up there with the best. The Blue Guitar [London: Viking, 2015] is the confessional monologue of a lapsed artist, chronic petty thief, occasional adulterer, runner-away from troubles and product of his somewhat chaotic life. That narrator, Oliver Orme, talks almost as well as John Banville writes and that is a serious compliment.

Spanning the somewhat fraught most recent year of Orme’s life it sees the events through his own self-critical (but sometimes self-pitying) eyes as he ‘steals’ his friend’s wife and, as that affair reaches its bathetic conclusion, finds himself back with his own wife who has something very interesting to tell him. What I have enjoyed in all the Banville works I have read is his gift for surprising similes, magical metaphors and attractive alliteration that adds to the poetic character of his prose.

Last night I had a strange dream, strange and compelling, which won’t disperse, the tatters of it lingering in the corners of my mind like broken shadows. I was here, in the house, but the house wasn’t here, where it is, but on the seashore somewhere, overlooking a broad beach. A storm was under way, and from the downstairs window I could see an impossibly high tide rolling in, the enormous waves, sluggish with the weight of churned sand, rumbling over each other in their eagerness to gain the shore and dash themselves explosively against the low sea wall, the waves were topped with soiled white spray and their deeply scooped, smooth undersides had a glassy and malignant shine. It was like watching successive packs of maddened hounds, their jaws agape, rushing upon the land in a frenzy and being violently repulsed.

Not much later in the book there is a passage that conveys his feelings of guilt and the strand of humour that, for the reader, is woven through the novel from first to last.

Caught, by God! Or by Gloria at any rate, which in my present state of guilty dread amounts to much the same thing. She has guessed where I am fled to. A minute ago the telephone in the front hall rang, the antiquated machine on the wall out there the palsied bell of which I had thought was surely defunct by now. I started in fright at the sound of it, a ghostly summons from the past. At once I rushed from the kitchen – I’ve been using the old wooden table under the window for a writing desk – and snatched the earpiece from its cradle. She spoke my name and when I didn’t answer she chuckled. ‘I can hear you breathing,’ she said. My heart in its own cradle was joggling madly. I’m sure that even if I had wanted to speak I wouldn’t have been able to. I had thought I was so safe! ‘You’re such a coward,’ Gloria said, still amused, ‘running home to Mother.’ My mother, I might have told her coldly has been dead for nigh on thirty years, and I’ll thank you not to speak mockingly of her, in however oblique a fashion. But I said nothing. There really wasn’t anything I could say. I had been run to earth; collared, caught.

There is tragedy that can make us laugh and humour that makes one weep with pleasure. The narrative is interspersed with painterly observations of the landscape and the ever-changing Irish sky. The prose is polished until it shines and, for those who like such things, I even spotted a chiasmus. If you haven’t already begun reading and revelling in John Banville’s prize-winning books, now is the time to start.

The post ‘The Blue Guitar’ by John Banville appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 23, 2015

‘1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear’ by James Shapiro

Many a bardophile will hope to find James Shapiro’s 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear [London: Faber & Faber, 2015] in their Christmas stocking. Not only is Shakespeare lauded as our greatest writer but many believe King Lear is his greatest play. Mine was a very early present and I have found it a fascinating study of the events in and around 1606 and how the Bard seems to have reacted to what were current events for him. Not least of these were the Gunpowder Plot and the efforts of the new king, James VI & I, to create the Union of his kingdoms.

Many a bardophile will hope to find James Shapiro’s 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear [London: Faber & Faber, 2015] in their Christmas stocking. Not only is Shakespeare lauded as our greatest writer but many believe King Lear is his greatest play. Mine was a very early present and I have found it a fascinating study of the events in and around 1606 and how the Bard seems to have reacted to what were current events for him. Not least of these were the Gunpowder Plot and the efforts of the new king, James VI & I, to create the Union of his kingdoms.

It was also a time of plague deaths and the consequent closing and re-opening of theatres in London which sent the several companies of players out to tour the provinces. Also to die during the year were the convicted plotters who had tried to destroy almost the entire governing elite of the country with one massive bomb. Why does this, as does Shakespeare always, seem so contemporary.

If you find history, literature and life at all levels of society interesting then there are hours of information, education and entertainment in this book written by one of the best of our current Shakespeare scholars, James Shapiro; a worthy successor to his earlier prize-winning 1599.

The post ‘1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear’ by James Shapiro appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

October 20, 2015

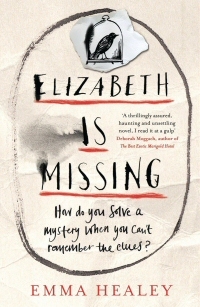

‘Elizabeth is missing’ by Emma Healey

Emma Healey’s book won the Costa Book Award in 2014 for a debut novel: Elizabeth is missing (London: Viking, 2014) richly deserved the prize. The author served a hard-working apprenticeship including taking a Masters degree in Creative Writing from the renowned University of East Anglia, during which she began her work on this moving story.

Emma Healey’s book won the Costa Book Award in 2014 for a debut novel: Elizabeth is missing (London: Viking, 2014) richly deserved the prize. The author served a hard-working apprenticeship including taking a Masters degree in Creative Writing from the renowned University of East Anglia, during which she began her work on this moving story.

Authors can set themselves interesting challenges. Healey chose to write this story from the viewpoint and within the confused mind of Maud who is slowly slipping into the penumbra of dementia. Maud’s recollection of past events is often sharper and less confused than her short term memory. She seeks to overcome her problem by writing notes to herself but too often she cannot make much sense of these notes herself. The one thing she is completely certain of is that ‘Elizabeth is missing.’ Elizabeth is her friend and contemporary who bonded with Maud as the pair of them worked as volunteers in the Oxfam shop. When she goes to report her friend’s disappearance to the police we learn that this is far from the first time she has done so but she cannot recall the earlier times. When she goes out shopping, she forgets what she needs and cannot find her note so, once more, she buys tinned peaches to add to her store cupboard full of them.

The author’s challenge is to make the narrative of an eighty-year-old dementia sufferer both credible in its confusion yet accessible to the reader, whose role is to note and accept the writer’s approach. Healey does this with great skill so that we seldom notice how well Maud is telling her story. The mask slips only once or twice when Maud recalls the ‘mad woman’ being run over and killed on the road, her foraged leaves and plants scattered around her ‘like an old Ophelia who’d mistaken the road for a river.’ Even so, it is a beautiful simile and I could be accused of nit-picking: forgive me Emma.

Emma Healey was motivated to research and write her novel by her two grandmothers, both of whom suffered from Alzheimer’s. Anyone who has an ounce of empathy will be moved by the way Maud’s narrative and the events of the story become progressively more confused in each succeeding chapter. Those with first-hand experience of the illness will find so many echoes of actuality.

Emma Healey was motivated to research and write her novel by her two grandmothers, both of whom suffered from Alzheimer’s. Anyone who has an ounce of empathy will be moved by the way Maud’s narrative and the events of the story become progressively more confused in each succeeding chapter. Those with first-hand experience of the illness will find so many echoes of actuality.

While Maud worries increasingly about Elizabeth, the story of her sister Sukie who disappeared with little or no trace seventy years before is intertwined, and clues and red herrings are interspersed cleverly. To find out if the two parallel stories finally converge, you will need to read the book as, according to my strict rules, the outcomes cannot be revealed. However, this beautiful book can be enthusiastically recommended to everyone.

The post ‘Elizabeth is missing’ by Emma Healey appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

Michael Johnston's Blog

- Michael Johnston's profile

- 4 followers