Michael Johnston's Blog, page 14

October 7, 2013

A forward thinking theme for Book Reading Groups: the Future as imagined in the Past

‘Future Imperfect’ might be a theme for book reading groups to pursue when planning a season of older literary novels. There is a fascination in reading accounts in literary novels of a future world written many years ago and to see how the mind-set of the period in which it was written colours the book’s picture of its own imagined future. Someone once remarked to me, “There’s surely no future in the prediction business.” but, in actual fact, there are many people who make a worthwhile living out of telling the rest of us what life is going to be like in 10, 20, or 50 years time. Businesses will pay serious money attempting to reduce uncertainty. Shell used to be famous for constructing future ‘scenarios’ to guide the company’s long term planning. However, we can now read authors who set their books in a future that is already, in calendar terms, part of our own past. However, close reading of these books will almost invariably reveal that, since the future is unknowable, projections into the decades and centuries ahead are conditioned by the issues and concerns that are part of contemporary thinking and debate at the time the book is being written. For today’s reader of futuristic novels, they are commentaries on what worried the world then and should provoke reflection on not just how right or how wrong the novelists were but rather on how relevant is their message for our own today.

Generally, futurologists are a gloomy lot; predicting floods, famines and enslavement of the masses if we were not, in fact, wiped out all together; but one, tongue in cheek, in 1931 predicted a Brave New World. Aldous Huxley envisaged a society some six hundred years in the future, where natural human reproduction has been replaced by not just in vitro fertilisation but the pregnancy and ‘birth’ all occurring in the laboratory and the output being graded from Alpha to Epsilon, the lower quality Deltas and Epsilons being the ones who did all the labouring and menial work but, being chemically conditioned, never found their lot unsatisfactory. Consumption is now a moral imperative to sustain output and employment. Apart from hypnopaedic learning (learning while you sleep) to reinforce the conditioning message that everything’s for the best in the best of all possible worlds, whatever your societal rank, there was blanket use of the hallucinatory drug soma and reproduction-free sex was a common way of spending the afternoon. What turns a funny novel into a social tragedy is the existence of native reserves, a tourist venue for the Alphas and Betas, and the discovery of John, illegitimate son of the current Director of Hatcheries and Conditioning, who is brought back to the ‘civilised’ world. The novel looks at the havoc this causes and which ends with two Alphas being exiled to the Falkland Islands and a tragic end for John.

Generally, futurologists are a gloomy lot; predicting floods, famines and enslavement of the masses if we were not, in fact, wiped out all together; but one, tongue in cheek, in 1931 predicted a Brave New World. Aldous Huxley envisaged a society some six hundred years in the future, where natural human reproduction has been replaced by not just in vitro fertilisation but the pregnancy and ‘birth’ all occurring in the laboratory and the output being graded from Alpha to Epsilon, the lower quality Deltas and Epsilons being the ones who did all the labouring and menial work but, being chemically conditioned, never found their lot unsatisfactory. Consumption is now a moral imperative to sustain output and employment. Apart from hypnopaedic learning (learning while you sleep) to reinforce the conditioning message that everything’s for the best in the best of all possible worlds, whatever your societal rank, there was blanket use of the hallucinatory drug soma and reproduction-free sex was a common way of spending the afternoon. What turns a funny novel into a social tragedy is the existence of native reserves, a tourist venue for the Alphas and Betas, and the discovery of John, illegitimate son of the current Director of Hatcheries and Conditioning, who is brought back to the ‘civilised’ world. The novel looks at the havoc this causes and which ends with two Alphas being exiled to the Falkland Islands and a tragic end for John.

Another bleak view of a future dystopia made up of three warring power groups, and which  ends with no relief in sight, is George Orwell’s 1984 in which one prole tempted to rebel against Big Brother is brought to heel and submission by cruel psychological terror in Room 101. The book created its own vocabulary with Newspeak being the word to describe the state propaganda emanating from the Ministry of Truth whose slogans included ‘War is Peace’ and ‘Freedom is Slavery’. Winston and Julia try to carry on a love affair out of sight of the ever present ‘Big Brother’ cctv but are discovered by the Thought Police and when, a long time after, they run across each other, they confess that each had betrayed the other. Of course, Orwell’s purpose was to rail against anti-libertarian tendencies that stalked the world, such as Stalinism and what would soon become McCarthyism. Orwell’s book was finished in 1948 and he inverted the last numbers of that year to create his title. As with the Huxley book, 1984 quickly became a classic and a part of the canon of English Literature. (Could that mean the Thought Police were successful after all?)

ends with no relief in sight, is George Orwell’s 1984 in which one prole tempted to rebel against Big Brother is brought to heel and submission by cruel psychological terror in Room 101. The book created its own vocabulary with Newspeak being the word to describe the state propaganda emanating from the Ministry of Truth whose slogans included ‘War is Peace’ and ‘Freedom is Slavery’. Winston and Julia try to carry on a love affair out of sight of the ever present ‘Big Brother’ cctv but are discovered by the Thought Police and when, a long time after, they run across each other, they confess that each had betrayed the other. Of course, Orwell’s purpose was to rail against anti-libertarian tendencies that stalked the world, such as Stalinism and what would soon become McCarthyism. Orwell’s book was finished in 1948 and he inverted the last numbers of that year to create his title. As with the Huxley book, 1984 quickly became a classic and a part of the canon of English Literature. (Could that mean the Thought Police were successful after all?)

Other books which could fit into this category include The Old Men at the Zoo by Angus Wilson, about what happens when a giraffe escapes, and other things besides, but, since I have still to read it, I cannot say more. H G Wells wrote about The Shape of Things to come but this has dropped off the modern radar. A more up-to-date book that I suggest is a mixture of future prediction, SF to a degree, and contemporary commentary is Pattern Recognition by William Gibson. I quote here from Wikipedia:

Pattern Recognition is a novel by science fiction writer William Gibson published in 2003. Set in August and September 2002, the story follows Cayce Pollard, a 32-year-old marketing consultant who has a psychological sensitivity to corporate symbols. The action takes place in London, Tokyo, and Moscow as Cayce judges the effectiveness of a proposed corporate symbol and is hired to seek the creators of film clips anonymously posted to the internet. The novel’s central theme involves the examination of the human desire to detect patterns or meaning and the risks of finding patterns in meaningless data. Other themes include methods of interpretation of history, cultural familiarity with brand names, and tensions between art and commercialization. The September 11, 2001 attacks are used as a motif representing the transition to the new century.

I set off to explore books written in the past and purporting to foretell the future and I justify the inclusion of Pattern Recognition by its being already 10 years old. As a way of getting to think seriously about modern data-mining techniques, which have expanded dramatically in the ten years since the book was published, and of the ways in which that accumulated knowledge of our consumer and political motivations and how to influence them, this is a seminal text.

The post A forward thinking theme for Book Reading Groups: the Future as imagined in the Past appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

September 18, 2013

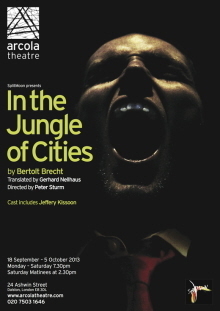

Brecht at the Arcola: SplitMoon present “In the Jungle of the Cities”

Having just come from seeing The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui at the Chichester Minerva Theatre and been bowled over, I am very tempted to go and see SplitMoon’s production of a young Brecht’s play, In the Jungle of the Cities which will be playing at the Arcola Theatre from today (18 September) directed by Peter Sturm.

Having just come from seeing The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui at the Chichester Minerva Theatre and been bowled over, I am very tempted to go and see SplitMoon’s production of a young Brecht’s play, In the Jungle of the Cities which will be playing at the Arcola Theatre from today (18 September) directed by Peter Sturm.

Brecht said himself, “You are in Chicago in 1912. You are about to witness an inexplicable wrestling match between two men and observe the downfall of a family that has moved from the prairies to the jungle of the big city. Don’t worry your heads about the motives for the fight, concentrate on the stakes. Judge impartially the technique of the contenders, and keep your eyes fixed on the finish.” The premiere in Munich in 1923 and was interrupted by Nazi hoodlums shouting and throwing stink bombs, suggesting it was as effective as a play! The play runs until 5 October.

The Arcola Box Office is at 020 7503 1646 or on line at www.arcolatheatre.com

The post Brecht at the Arcola: SplitMoon present “In the Jungle of the Cities” appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

Theatre-goers (and book reading groups) should start reading now – Some great stage adaptations are coming up

Theatre-going book lovers have three wonderful novels they should be reading over the next two or three months, in anticipation of forthcoming stagings at the RSC, Stratford-upon-Avon and The Orange Tree, Richmond.

Over the years, many books and films have been successfully or otherwise adapted for the theatre. As long as we remember that, in a different medium, the story becomes a different work of art, standing or falling on its own artistic merits, then we can enjoy both versions. This autumn, the enterprising and intimate theatre-in-the-round, the Orange Tree in Richmond is staging a trilogy of plays adapted from Middlemarch by George Eliot; ‘Dorothea’s Story’, ‘The Doctor’s Story’ and ‘Fred and Mary’ which première in October, November and December respectively. The adaptation is by Geoffrey Beevers who is also directing the season.

Over the years, many books and films have been successfully or otherwise adapted for the theatre. As long as we remember that, in a different medium, the story becomes a different work of art, standing or falling on its own artistic merits, then we can enjoy both versions. This autumn, the enterprising and intimate theatre-in-the-round, the Orange Tree in Richmond is staging a trilogy of plays adapted from Middlemarch by George Eliot; ‘Dorothea’s Story’, ‘The Doctor’s Story’ and ‘Fred and Mary’ which première in October, November and December respectively. The adaptation is by Geoffrey Beevers who is also directing the season.

Ambitiously, the Orange Tree, under Sam Walters’s artistic direction, is staging not only each separate play but some all-day three-play days. The idea of separating out the strands of the novel which George Eliot wove together makes a great deal of dramatic sense. What the patient reader can adapt to as s/he reads through the book, with its bewitching ironies and occasional voice-of-the-author interjections, would be confusing and distracting in the stricter confines of a couple of hours on stage.

Beevers will tell the story of the saintly Dorothea so sadly let down in her expectations by that dry-as-a-stick Casaubon and how she eventually finds love with Ladislaw; he will recount the adventures, both medical and matrimonial of Dr Lydgate; and he will tell the story of true love between the feckless Fred and the angelic Mary.

So, now is the time to get hold of Middlemarch and (re)read it lovingly. The book and the prose date from the period of the three-volume ‘loose baggy monsters’, in the words of Henry James, who wrote a few of these himself. However, the wit and the intellect of the author and the humanity of the story make for the book’s enduring hold on novel readers. If you do not find time to read the book before seeing the plays, you are almost certain to want to read it afterwards.

Next on the ‘must read again’ list for theatre-going novel readers are the two Tudor novels by Hilary Mantel; Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies charting the rise and rise of Thomas Cromwell at the court of Henry VIII, which are being adapted for the stage by Mike Poulton for the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford-upon-Avon, opening in mid-December, and will also be screened around the same time by the BBC in their own adaptation.

Next on the ‘must read again’ list for theatre-going novel readers are the two Tudor novels by Hilary Mantel; Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies charting the rise and rise of Thomas Cromwell at the court of Henry VIII, which are being adapted for the stage by Mike Poulton for the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford-upon-Avon, opening in mid-December, and will also be screened around the same time by the BBC in their own adaptation.

Mantel is already hard at work on what will be the third and final volume of this Tudor tale which will take the reader to the death of Thomas Cromwell, central character of all three books. Having won two already for the first two volumes, bookmakers might not give you too long odds on Mantel winning another Man Booker Prize with this third volume, not due to appear in print until next year at the earliest.

How long it will then take both the RSC and the BBC to present it remains to be seen. Such is the complexity of their background stories; as well as the clarity of their language of course; it would make more sense to have read the books first: so this is fair warning. The RSC Box Office is taking bookings for both plays already: my seats are booked for a long weekend next March.

The post Theatre-goers (and book reading groups) should start reading now – Some great stage adaptations are coming up appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

September 16, 2013

Russ Litten’s new detective novel Swear Down is a possible for Crime Book Reading Groups

[image error]This book came to me through the book club Litro and is an example of a book I would not have bought myself but which I’m glad to have read. Swear Down tells the story of the patient detective work of newly promoted, and newly returned from holiday, Detective Sergeant Ndekwe who is confronted not only with a superior officer who fills his day with biscuits and coffee, counting the days to retirement, but by a case of murder by a single stab wound to which two men have confessed. Since there was only one assailant and no weapon yet discovered, is he confronted with mutually exclusive confessions neither of which can be proved.

Litten uses the literary device the Sergeant and the Inspector playing over the recordings of the two interviews as a means of telling the reader the back story. Ndekwe listens patiently to tease out the story while the Inspector listens to it almost as background white noise. The recorded interviews give place to the live interviews as Ndekwe pushed his questioning forward and questions others not under arrest for the crime. Again, the two accounts of the young black man and the old and feckless white man diverge although they both drove out of London up to Hull to ‘escape’ from the consequences of the crime they both claim to have committed.

The connection that he eventually makes and the old man’s secret which eventually helps him solve the case is embargoed under the Reviewer’s Non-spoiler Convention but they make sense. However, the book’s secondary roles, like Ndekwe’s wife, or among the police and the juvenile, criminal fraternity lack depth and, for my taste, could have been made more three-dimensional. That said, this is a well-constructed and sufficiently page-turning book to be worth the read. Score: 7 out of 10.

The post Russ Litten’s new detective novel Swear Down is a possible for Crime Book Reading Groups appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

September 6, 2013

Booker Long List contender for Book Reading Groups: The Marrying of Chani Kaufman is highly recommended

We will find out any day now if this debut novel makes the Short List but The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris is an ideal book for Reading Groups. Full marks to the Sandstone Press up in the Highlands for picking this up and running with it. (I wonder if anyone has ever sent them a novel about the Wee Frees: I fear it would not have the same quality of humour.)

Harris tells the story of two Golders Green couples from different generations, linked by belonging to a strongly Orthodox Jewish sect, the Charedi. It relates with a light and always sympathetic touch the struggle of Baruch to marry the girl of his choice and of Chani to overcome the snobbish objections of her future mother-in-law and the disparity in worldly wealth between the groom and his self-chosen bride.

Harris tells the story of two Golders Green couples from different generations, linked by belonging to a strongly Orthodox Jewish sect, the Charedi. It relates with a light and always sympathetic touch the struggle of Baruch to marry the girl of his choice and of Chani to overcome the snobbish objections of her future mother-in-law and the disparity in worldly wealth between the groom and his self-chosen bride.

Their story is contrasted with that of the Rebbetzin, wife of Rabbi Zilberman, and her passionate encounter with her future husband while they are in Jerusalem but then the steadily deepening religious observance of Chaim Zilberman.

Weaving in and out of these stories is the tragic-comedy of Avromi Zilberman, their son and Baruch’s best friend, and his encounter with a beautiful Gentile.

Like every good novel, a new, strange and sometimes wonderful world is opened up for the reader’s inspection. This one takes us into the mind-set of a community feeling, much of the time, under threat from the outside world and seeking to maintain its God-given standards and its commitment to prayer and observance in the face of ignorance and incomprehension from those who can have no knowledge or feeling for their traditions. There are also internal battles to fight. The rule is no television but, for a while, the Zilberman family bond in front of a tiny TV in the bedroom where they sin by watching football together. Alas, when the Rabbi is promoted in his synagogue he feels the TV has to go. The novel asks how far the contemporary world of colour and cross-pollination of ideas can be allowed into a religiously-observant life without risking possible fatal damage to many centuries of faith and tradition.

Above all, the humanity and reality of the main characters comes through while the character actors, like the mother-in-law and the matchmaker, are picked out in the fine detail that allows the reader to feel for them as well.

This is a book in the tradition of Issac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Potok, so, to Eve Harris, we say mazel tov! And every good wish for the Booker Prize in 2013. 8 out of 10.

The post Booker Long List contender for Book Reading Groups: The Marrying of Chani Kaufman is highly recommended appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

August 30, 2013

Barbara Kingsolver’s first novel should be on Book Reading Group lists: It is a classic!

When, some time back, I saw Barbara Kingsolver had won a prize for her literary fiction The Lacuna, set in Mexico, I read it with great pleasure and then kept seeing references to how highly readers had rated her first novel,. So I bought a copy but only managed to take it down off the shelf this month. That’s a shame because her book should feature on any serious book lover’s ‘must read’ list.

The story opens gently with a mother recalling, from her present-day home on Sanderling Island, Georgia, how life was for her back in the 1960s, the era of Sputnik, of the election of JFK and how the world was polarised between the those who felt the land of the free and the home of the brave had the only viable formula for success and those who felt that Communism and the Soviet Union had all the right answers. It was the era when America seemed to believe and act on the principle that whoever was not for them must be against them and that neutrality was simply ignoring reality. How much contact with reality some Americans had can perhaps be measured by the opening sentence of the main story, narrated by one of the daughters of a Southern Baptist minister who chose that time of all times to take his entire family to the Congo to save souls for Jesus.

The story opens gently with a mother recalling, from her present-day home on Sanderling Island, Georgia, how life was for her back in the 1960s, the era of Sputnik, of the election of JFK and how the world was polarised between the those who felt the land of the free and the home of the brave had the only viable formula for success and those who felt that Communism and the Soviet Union had all the right answers. It was the era when America seemed to believe and act on the principle that whoever was not for them must be against them and that neutrality was simply ignoring reality. How much contact with reality some Americans had can perhaps be measured by the opening sentence of the main story, narrated by one of the daughters of a Southern Baptist minister who chose that time of all times to take his entire family to the Congo to save souls for Jesus.

We came from Bethlehem, Georgia, bearing Betty Crocker cake mixes into the jungle.

Head of the family, preacher Nathan Price for whom it becomes more and more clear that this is not just a mission but an obsession, his wife and his four children are in for progressively more and more disturbing encounters with reality, deep and remote in the Congolese jungle at that moment in history when the Belgians turned the country over to the Congolese and the Americans took fright at the ‘communistic’ tendencies of the democratically elected leader, Patrice Lumumba and acted against him.

Kingslover unfolds the story a step and a disaster at a time, through the voices of the mother and her four, very different daughters. An enduring joy of the book is the way in which the author successfully inhabits the characters of these five women from whom we hear the story related, each seeing events from their very personal points of view. While twin Leah seems at first to yearn for her father’s affections and tries to support him in all he does, gradually she becomes aware of just how large are the blinkers her father wears. She becomes more involved in the life and education of the children and grows to love the people and even the country. Her ‘crippled’ non-identical twin Adah, who chooses not to speak, has an inner and more intellectual life in which she revels in words, palindromes and language. Since she is hemiplegic, her left side drags and she is always the one trailing behind. At one point, when the whole village flees a column of fire ants marching through, Adah sees her mother choose the youngest, Ruth May, to carry into a canoe to escape. This denial of love is the low point from which she has to work for the rest of the book to recover.

Ruth May is the one who, like little children everywhere, adapts and integrates into the life of the village, teaching the Congolese children to play ‘Mother may I?’ (like ‘What time is it Mr Wolf?’ if you know that better) which they chant phonetically. Like her elder sister, Rachel, but for a different reason, she will never leave Africa. Rachel is the one who takes an instant dislike for everything that is not what she was used to in America; which means almost everything she finds there.

I didn’t much care for looking at these men in the pageant. We aren’t all accustomed to the African race to begin with, since back home they keep to their own parts of town. But here, of course, with everyplace being their part of town. Plus, these men in the pageant were just carrying it to the hilt. I didn’t see there was any need for them to be so African about it.

Rachel has another talent. She is the perfect modern Miss Malaprop, using words to mean what she thinks they mean, which adds delightfully to one’s picture of this pert Miss America. Don’t worry about her, though. She has a hard and self-protective character that will see her survive the worst that life, nature and the climate combine to throw at her and she will finish up in the French Congo doing well. But we shall come to that.

The extended drought seems about to finish them off, although father Nathan sees it as the Lord’s work, seeking to show everyone, including his family, the errors of their ways. He, of course, is never wrong. But disaster strikes the women and, as the rains begin to fall in torrents, they abandon him and simply walk away and leave him.

The final third of the book sets down the different accounts of the women, their exodus and their later lives over the next three decades as they face up to their current lives and look back to see how their spell in that Congolese village has shaped their ends. It is ironic that the one that turns out to be least changed as a character is Rachel who still sees the world through her all-American 1960s tunnel vision. It is beautiful and moving that it is Ruth May who provides the extended coda.

This book is a parable for its times; one which seems even more relevant today than it did when it was first published in 1998; although I doubt if Rachel would ever read it. You should read it in your Book Reading Group and debate its place alongside other classics like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mocking Bird or possibly Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. I have to rate this at 9.5 out of 10.

The post Barbara Kingsolver’s first novel should be on Book Reading Group lists: It is a classic! appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

August 26, 2013

Bank Holiday reading for Book Groups? Two magical works of literature to compare and contrast

Here are two classic novels from very different parts of the world but they have in common a degree of magical realism that adds zest to their stories that should appeal both to lovers of literature in general and book reading groups in particular. As it happens, both were published in their original languages in the latter 1960s and distinguished critics as well as millions of readers have acclaimed them as two of the very best works of literature in any language in the twentieth century. Both tell tall tales with an ironic twist. I am referring to The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov and One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez.

Bulgakov had the sort of tormented life that afflicted free-thinking writers in the Soviet Union under Stalin. Although Stalin did, at one point, intervene to let him continue working in the theatre and writing, the atmosphere was still so restrictive and stifling that, when he organised a private reading of what he called his ‘sunset’ novel, and crowning literary achievement, to a circle of friends in 1939, several tried to persuade him not to publish. In fact, it was officially censored. Bulgakov died the following year of a hereditary kidney disease and it was left to his third wife and widow, perhaps the inspiration for the character Margarita, to struggle to have the book published. It finally appeared in the Soviet Union, in a truncated version, in 1966. It appeared in the West later and I have read The Master and Margarita in its translation by Michael Glenny [London: Harvill Press, 1967]. I do not know the later and highly regarded translation, based on a more complete version of the original, by Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O’Connor, but with annotations and an afterword by Ellendea Proffer, it has much to commend it [New York: Vintage Books, 1996.]

Bulgakov had the sort of tormented life that afflicted free-thinking writers in the Soviet Union under Stalin. Although Stalin did, at one point, intervene to let him continue working in the theatre and writing, the atmosphere was still so restrictive and stifling that, when he organised a private reading of what he called his ‘sunset’ novel, and crowning literary achievement, to a circle of friends in 1939, several tried to persuade him not to publish. In fact, it was officially censored. Bulgakov died the following year of a hereditary kidney disease and it was left to his third wife and widow, perhaps the inspiration for the character Margarita, to struggle to have the book published. It finally appeared in the Soviet Union, in a truncated version, in 1966. It appeared in the West later and I have read The Master and Margarita in its translation by Michael Glenny [London: Harvill Press, 1967]. I do not know the later and highly regarded translation, based on a more complete version of the original, by Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O’Connor, but with annotations and an afterword by Ellendea Proffer, it has much to commend it [New York: Vintage Books, 1996.]

The story alternates between two locations; Russia in the 1930s and Jerusalem around the time of Pontius Pilate’s trial of Yeshua about which the Master is trying to write his own novel. Satan, in the mask of Professor Woland, with a retinue including an upright-walking, talking black cat called Behemoth, arrives in Moscow and by magic and deceit takes over the apartment of the bureaucrat Berlioz. Woland predicts that Berlioz will be decapitated by a young Soviet woman, and that is exactly what happens when he ‘accidentally’ slips on a slick of sunflower oil and falls under the wheels of a passing streetcar driven by a young woman. (This was written at a time when apartments were so scarce that some might well have contemplated murdering the sitting tenants.) Woland continues to wreak havoc in Moscow but he does return a copy of his manuscript to the Master with the words that have entered the Russian language, “Manuscripts don’t burn.” I will not attempt a plot summary but simply say that in the second part of the novel, the Master’s young mistress Margarita works to rescue him from the asylum to which he has been banished. The novel has instances of miraculous teleportation and, overall, the air of both charivari and magical realism and will captivate all but the most literal minded.

[image error]If one is looking for arresting opening statement, there is much to commend the first sentence of One Hundred Years of Solitude by the acknowledged leader of South American writers of the last century. “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember the distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” [London: Penguin, 2007, translated by Gregory Rabassa.] The Colonel’s father, José Arcadio Buendía, had founded the village of Macando and the novel takes the history of Macondo down through seven generations of the Buendía family. Many critics interpret the story as a critical metaphor for the story of Colombia, from the colonial rule of Spain and onwards through events such as the Thousand Days War (1899-1902) and the neo-colonial ‘rule’ of the American United Fruit Company, ‘disguised’ in the novel as the American Fruit Company, the arrival of life-changing inventions such as the cinema and the automobile and brutalities like the industrial relations policy of using the military to massacre striking workers.

It is the founding father’s solipsistic belief that Macondo is an island rather than a remote village of a larger country that encourages the family’s inward looking view of events. José Arcadio flees from a duel in which he has killed his opponent and has a dream. Buendía dreams of a city of mirrors named Macondo and decides to establish a new town on the spot. While he is the patriarch, the figure who oversees six of the seven generations is his wife, the matriarch, Úrsula Iguarán. She manages this by living to be 130 years old. She is the one who, despite previous failures by the menfolk, finds a way out of Macondo.

Apart from its well-known ‘signatures’ of magical realism and fatalism, there is the continuing story of the undecipherable manuscript put into their hands by an old gypsy and, as the story unfolds, fewer an fewer seem aware of its existence until, finally, someone discover the message hidden within it. Since book groups and lovers of literature generally will know of both of these books, no further exposition of the plot is appropriate. Suffice to say that if you haven’t already packed your holiday reading, think about laying aside the Booker Long List until the Short List is known and take these two books with you instead.

The post Bank Holiday reading for Book Groups? Two magical works of literature to compare and contrast appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

August 11, 2013

Book Reading Groups Recommendations: Two “Foreign” Books – read dangerously!

Bought in a bookshop in Caen, Normandy, to read with my lunch in a wine shop, Les Domaines qui Montent (which gets four stars from me as a restaurant), I have been reading the first novel by Muriel Barbery, Une Gourmandise (in English Gourmet Paradise translated by Alison Anderson) and needed to have several lunches there to make progress through the book and the menu.

The story is of a world-famous and very-much-feared critic whose verdict could make or break the reputation of a chef and his restaurant. And this particular Titan, or tyrant, is dying. As he lies in his room, he searches in the taste buds of his imagination for an elusive savour that he somehow cannot quite recall. Interspersed between the chapters of his reminiscences of meat, fish, soup, raw vegetables, mayonnaise and whisky, are the feelings of family and acquaintances whose lives he has affected, not forgetting his cat. They are a fascinating counterpoint and, together, paint a very different image of the dying man. Surprisingly, his wife still loves him. Not surprisingly for the loving way in which Barbery describes and makes us drool over the gourmandising, the book won a prize in 2000 for the best literary book about gourmet matters. I recommend a 2012 dry white wine from Gers to go with the book.

Barbery went on to use the technique of multiple narrators in another wonderful book, The Elegance of the Hedgehog which, like Gourmet Paradise won prizes for its author. I will give Gourmet Paradise 8 out of 10 (and The Elegance of the Hedgehog 8.8 out of 10).

I have to declare an interest in the next book, Quesadillas by the Mexican writer Juan Pablo Villalobos. I subscribe to the publisher And Other Stories who brings out around ten books a year and this is the second I have received. On the strength of the first two I am certainly looking forward to the third. Quesadillas is translated beautifully from the original Spanish by Rosalind Harvey. The little glossary at the back of the book explains that a quesadilla is a tortilla filled with cheese or other savoury ingredients.

I have to declare an interest in the next book, Quesadillas by the Mexican writer Juan Pablo Villalobos. I subscribe to the publisher And Other Stories who brings out around ten books a year and this is the second I have received. On the strength of the first two I am certainly looking forward to the third. Quesadillas is translated beautifully from the original Spanish by Rosalind Harvey. The little glossary at the back of the book explains that a quesadilla is a tortilla filled with cheese or other savoury ingredients.

The narrator looks back on his childhood experiences surviving on a diet of quesadillas whose quality and quantity varies according to the family’s finances and how many there are to feed. Academics tend to call such books Bildungsroman but we can simply call this an angry, scabrous but humorous account of a Mexican childhood far from the fleshpots and, often enough, the cheesepots as well. On no-cheese days, his mother would write the word ‘cheese’ on the inside of the tortilla. Orestes has a schoolteacher father who has given all his children classical Greek names, including ‘the pretend twins’ Castor and Pollux who are non-identical and, as the story opens, no longer there, having disappeared in a supermarket. A wealthy Polish family; father, mother, and teenage son the same age as Orestes, build a deluxe villa next door and tensions mount between the boys. Jarek has been everywhere while Orestes hasn’t been anywhere. Orestes’s visits to Jarek’s house are a torment for Orestes’s mother who is fearful he will break something (or maybe even steal something!) and his family will have to pay for it. Eventually, Orestes and his older brother, Aristotle, do rob the Pole’s house and run away; Aristotle seeking the pretend twins who have, he is convinced, been abducted by aliens and Orestes seeking just to get away. At this point, elements of South American magical realism enter the narrative but with a very light touch. The plot develops to a satisfying, and realistically magical conclusion that you will need to read the book to find out. I will rate this at 7.5 out of 10.

Book reading groups should seek to winden their reading horizons by including at least one, better two, “foreign” books every season. These two would do well for a start.

The post Book Reading Groups Recommendations: Two “Foreign” Books – read dangerously! appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

August 8, 2013

Stoner by John Williams: A Vintage American novel for Book Reading Groups

I am sure book reading group members have this experience too. Every so often serendipity, synchronicity, or simply sheer chance bring a book to my attention by an author who I am embarrassed to admit I had never heard of but will now never forget. Such a book has the simple title Stoner by John Williams and it was first published in 1965 in the USA: where was I looking at the time that I did not spot it then, or even in 1973 when it was first published in the UK?

Stoner, reissued now by Vintage Classics, is the life story of an able man with a stubborn streak. Born to work the soil like his parents and forefathers, his abilities attract the attention of the County Agent in rural Missouri who tells his parents he should take the new four-year agricultural degree now being offered at the University in Columbia. Although it means losing his free labour, they encourage him to go. There, it happens that a required module for all students is a one-semester survey of English literature, taught by a jaded man in his late fifties who yet manages to blow on the spark of interest that began to glow in William Stoner’s imagination. He abandons agriculture and completes his degree in English Literature. It is only when he completes his first degree that he breaks it gently to his parents that he is not coming back to work on the farm.

Stoner, reissued now by Vintage Classics, is the life story of an able man with a stubborn streak. Born to work the soil like his parents and forefathers, his abilities attract the attention of the County Agent in rural Missouri who tells his parents he should take the new four-year agricultural degree now being offered at the University in Columbia. Although it means losing his free labour, they encourage him to go. There, it happens that a required module for all students is a one-semester survey of English literature, taught by a jaded man in his late fifties who yet manages to blow on the spark of interest that began to glow in William Stoner’s imagination. He abandons agriculture and completes his degree in English Literature. It is only when he completes his first degree that he breaks it gently to his parents that he is not coming back to work on the farm.

Going on to take his Masters degree and then working part-time as an instructor while progressing to his PhD, Stoner reinvents himself as a scholar and teacher. (He reminds me of the Scots ‘lad o’ pairts’ who is spotted in his early years in the parish school and encouraged to blossom by his teachers and the whole education system, goes on to the High School and University and finds, as one sad consequence, he can no longer talk with his parents about topics of mutual interest and yet, because of his origins, is not entirely accepted by his more sophisticated peers.) In his final year, Stoner’s English tutor talks to him seriously.

Sloane tapped the folder of papers on his desk. “I am informed by these records that you come from a farming community. I take it that your parents are farm people?”

Stoner nodded.

“And do you intend to return to the farm after you receive your degree here?”

“No, sir,” Stoner said, and the decisiveness of his voice surprised him. He thought with some wonder of the decision he had suddenly made.

Sloane nodded. “I should imagine a serious student of literature might find his skills not precisely suited to the persuasion of the soil.”

“I won’t go back,” Stoner said as if Sloane had not spoken. “I don’t know what I’ll do exactly.” He looked at his hands and said to them, “I can’t quite realise that I’ll be through so soon, that I’ll be leaving University at the end of the year.”

Sloane said casually, “There is, of course, no absolute need for you to leave. I take it that you have no independent means?”

Stoner shook his head.

[…]

“But don’t you know, Mr Stoner?” Sloane asked. Don’t you understand about yourself yet? You’re going to be a teacher.”

[…]

“How can you tell? How can you be sure?”

“It’s love, Mr Stoner,” Sloane said cheerfully. “You are in love. It’s as simple as that.” [pp. 19/20]

Stoner does love English literature but he is still in some respects a naïve and awkward farm boy. This is pointed up when, at a University event, he catches sight of Edith Elaine Bostwick, is smitten, and asks a colleague for help.

“I want you to introduce me,” Stoner said. He felt his face warm. “Do you know her?”

“Sure,” Finch said. The start of a grin began to tug at his mouth. “She’s some kind of cousin of the dean’s, down from St Louis, visiting an aunt.” The grin widened. “Old Bill. What do you know. Sure, I’ll introduce you. Come on.” [p. 48]

Alas, of all the women in the room, Elaine was probably the worst choice but they were neither to know this until after they married only a few months later. John Williams does not spare her in his character sketch.

She was educated upon the premise that she would be protected from the gross events that life might thrust in her way, and upon the premise that she had no other duty than to be a graceful and accomplished accessory to that protection, since she belonged to a social and economic class to which protection was an almost sacred obligation. She attended private schools for girls where she learned to read, to write, and to do simple arithmetic; in her leisure she was encouraged to do needlepoint, to play the piano, to paint water colors, and to discuss some of the more gentle works of literature. She was also instructed in matters of dress, carriage, ladylike diction, and morality.

Her moral training, both at the schools she attended and at home, was negative in nature, prohibitive in intent, and almost entirely sexual. The sexuality, however, was indirect and unacknowledged; therefore it suffused every other part of her education, which received most of its energy from that recessive and unspoken moral force. She learned that she would have duties toward her husband and family and that she must fulfill them. [p. 54]

The nature of these duties becomes clear on their disastrous wedding night and sets the pattern for a life in which, Stoner realises, he will have to compromise, and do it her way! There is one brief period when Edith suddenly craves motherhood and demands sex until she becomes pregnant but seldom if ever thereafter. They pursue their separate lives and Stoner rises very slowly to the level of tenured associate professor, very much in love with his only child, Grace.

University politics and personalities do intrude when he declines promotion to Head of Department and the newly appointed Head and he manage to fall out spectacularly, a rancorous feud that persists for the rest of Stoner’s life. He also crosses swords with an erratic and, in Stoner’s view, incompetent student whom he wants to fail but the Head of Department wants to pass with distinction, maybe because both are physically handicapped. By this time, Stoner has fallen in love with a young graduate student and it is their affair that is both the most glorious and, inevitably, the most tragic event of his life.

John Williams prose is matter-of-fact, never florid but is masterful in the way it moves events forward relentlessly. Subtle wit is uncovered in every paragraph; a book to savour and to reread to which I will give a well-deserved 8.5 out of 10.

The post Stoner by John Williams: A Vintage American novel for Book Reading Groups appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

August 1, 2013

Book Reading Groups: Review of “Mr Penumbra’s 24-hour Bookstore”

Robin Sloan’s first full-length novel is a book for today in every sense of the word; ideal for book reading groups of all ages. It has only just been published by Atlantic Books in the UK. The author is young and tech-savvy; he lives in San Francisco where the book is set; he has done his research; and, best of all, he writes with a touch that James Thurber, Dorothy Parker and S J Perelman would have admired and commended.

Why did he write it? Not a very subtle question at the best of times but Sloan himself says: I wrote this book because it’s the one I wanted to read, and I tried to pack it full of the things I love: books and bookstores; design and typography; Silicon Valley and San Francisco; fantasy and science fiction; quests and projects. If you love those things too, I hope and believe you will enjoy a visit to the tall skinny bookstore next to the strip club. I couldn’t have put it more neatly myself. The book’s hero (and the word suits the young man) is Clay Jannon, who is out of a job as a web-designer, “a result of the great food-chain contraction that swept through America in the early twenty-first century, leaving bankrupt burger chains and shuttered sushi empires in its wake. […] The whole economy suddenly felt like a game of musical chairs, and I was convinced I needed to grab a seat, any seat, as fast as I could.” Walking for miles, eyes peeled for ‘help wanted’ signs, Clay finally sees, of all things, a 24-bookstore wanting someone for the late shift.

Why did he write it? Not a very subtle question at the best of times but Sloan himself says: I wrote this book because it’s the one I wanted to read, and I tried to pack it full of the things I love: books and bookstores; design and typography; Silicon Valley and San Francisco; fantasy and science fiction; quests and projects. If you love those things too, I hope and believe you will enjoy a visit to the tall skinny bookstore next to the strip club. I couldn’t have put it more neatly myself. The book’s hero (and the word suits the young man) is Clay Jannon, who is out of a job as a web-designer, “a result of the great food-chain contraction that swept through America in the early twenty-first century, leaving bankrupt burger chains and shuttered sushi empires in its wake. […] The whole economy suddenly felt like a game of musical chairs, and I was convinced I needed to grab a seat, any seat, as fast as I could.” Walking for miles, eyes peeled for ‘help wanted’ signs, Clay finally sees, of all things, a 24-bookstore wanting someone for the late shift.

Now I was pretty sure “24-hour bookstore” was a euphemism for something. It was on Broadway, in a euphemistic part of town. My help-wanted hike had taken me far from home; the place next door was called Booty’s and it had a sign with neon legs that crossed and uncrossed.

The self-styled ‘custodian’ of the store, Mr Penumbra explains that while he does look for employees with some enthusiasm for books this is no ordinary bookstore. Clay gets the job. He becomes the night clerk, taking over from another employee in the late evening and handing the watch back to Mr Penumbra in the morning. But the store is not open 24 hours per day to cope with a steady flow of customers. In fact, there are scarcely any and most of the shop’s occasional traffic consists of strange infrequent but regular callers who come in and ask for a book by author’s name. Clay tracks its location on the store’s elderly Mac and then shins up a ladder to retrieve it and lend it out to the borrower on production of their membership card. Clay is forbidden to “browse, read, or otherwise inspect the shelved volumes. Retrieve them for members. That is all.” However, he must make a detailed note on how the caller seemed, was dressed, and what he or she returns and takes out. The shop’s logbooks, labelled NARRATIO and with sequential Roman numbers, seem to go back a long, long way.

Inevitably, Clay breaks the rules and finds that every one of the books seems to be alphabetic gibberish. That just gets him going; he’s a geek, or do I mean nerd, after all; and he uses his computing knowledge and skills to try and crack what might be code. At the same time, he writes an algorithm to allow him to make a computer based 3-D model of the store on his own laptop including all the books’ locations. What would you do in the middle watch, from midnight until four in the morning? He does not make progress until, one night, he ‘borrows’ an earlier volume of the logbooks, copies the pages and analyses the pattern of borrowings of the callers against their location on the shelves. That’s when he makes his first big discovery.

And that’s where any further revelation of the storyline must stop. Of course, there is some love interest; there is a visit to Google’s HQ; some very futuristic but entirely credible computer programming (programming knowledge inessential) and all these satisfying morsels are enfolded in a tale told with self-deprecatory humour. There are pen-sharp portrayals of identifiable 21st century characters that are both witty and empathetic.

Almost all of my reading is a pleasure; but I seldom come across novels that are such rumbustious fun to read; subtle gags and mordant wit on every page. I admit I was wary of it when I came through my letterbox as part of the Litro book-subscribers selection process but I have to say now that it is one of the most satisfying and intriguing books of my reading year and I will rate it an exceptional 9.2 out of 10. More please Robin!

The post Book Reading Groups: Review of “Mr Penumbra’s 24-hour Bookstore” appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

Michael Johnston's Blog

- Michael Johnston's profile

- 4 followers