Michael Johnston's Blog, page 13

November 25, 2013

Booker Prize short-listed Ruth Ozeki tells “A Tale for the Time Being” and does so very well

Designers are taught that to bring two opposing colours closer together you need to add some of each colour into the other; which is just what Ruth Ozeki does in her fascinating, Booker short-listed novel A Tale for the Time Being. A ‘novelist’ with an American father and Japanese mother finds a diary and notebook washed up on a lonely island in British Columbia and written by a Japanese girl who spent her early years living in California. So the writer, called ‘Ruth’, can understand many of the Japanese aspects of the girl’s account of her troubled life and, fortunately for us, the girl, Naoko, writes in English. A bond is established; not just between writer and diarist but between them both and the reader.

Designers are taught that to bring two opposing colours closer together you need to add some of each colour into the other; which is just what Ruth Ozeki does in her fascinating, Booker short-listed novel A Tale for the Time Being. A ‘novelist’ with an American father and Japanese mother finds a diary and notebook washed up on a lonely island in British Columbia and written by a Japanese girl who spent her early years living in California. So the writer, called ‘Ruth’, can understand many of the Japanese aspects of the girl’s account of her troubled life and, fortunately for us, the girl, Naoko, writes in English. A bond is established; not just between writer and diarist but between them both and the reader.

Another thought occurs to me: in sociological experiments, it is often impossible to exclude the effects of the observer’s reactions and emotions which, in turn, will affect the outcome of the experiment. So it is with this book, where the slowly building tension in Naoko’s story provokes alarm, anxiety, frustration and even depression in ‘Ruth’ and, as you will surely confirm, in the reader too. Academic theorists will recognise the symptoms of ‘reader response theory’ and this book would make an almost ideal subject for any 21st Century contemporary fiction course.

Naoko has been uprooted from her comfortable Californian childhood and, as a vulnerable teenager, returned to Japan with her now-unemployed father. Her knowledge of her mother tongue is sketchy and her school-fellows bully her mercilessly. Finding a blank notebook bound into the hollowed-out cover of `À la recherché du temps perdu she buys it for her personal diary and, for the time being, wonders about time, about being and, just as often, about not being. Since her father is suicidal and her mother out working all day, she is very fortunate in have a good relationship with her centenarian great-grandmother Jiko who is a Zen Buddhist nun with a timeless philosophy. She pours out her heart into the diary and, somehow, unexplained, some little time after the tsunami that wrecked Fukushima power station and much else besides, this long diary, written over a period of three or more years, this carefully wrapped and packed notebook washes up in a barnacle encrusted polythene bag that ‘Ruth’ notices glinting in the low sun on her island shore.

Ruth Ozeki, the novelist (with an American father and a Japanaese mother who now divides  her time between New York and British Columbia) who wrote this book, is married to Oliver and this is her third novel. The central character in her book just happens to be a novelist called ‘Ruth’ who is married to an ecologist called ‘Oliver’. So we really have to keep in mind Waugh’s epitaph to Brideshead Regained: “I am not I; thou art not he or she; they are not they”: this is a work of fiction. (And if you read Philip Roth you are already familiar with such mind games.) As Naoko finds out more about her great-uncle who was one of the last kamikaze airmen and discovers his secret diary (written in French to complicate matters), she bundles these in with her notebook. ‘Ruth’ and the reader read the grim truth about the sadistic training and exploitation of the young men the failing Japanese military abused in this way. However, if the reader thinks that’s the most harrowing part of the story, be warned, the emotional turmoil moves up several gears as Naoko’s world collapses and, one can argue, in consequence, so is ‘Ruth’s’ put at great risk.

her time between New York and British Columbia) who wrote this book, is married to Oliver and this is her third novel. The central character in her book just happens to be a novelist called ‘Ruth’ who is married to an ecologist called ‘Oliver’. So we really have to keep in mind Waugh’s epitaph to Brideshead Regained: “I am not I; thou art not he or she; they are not they”: this is a work of fiction. (And if you read Philip Roth you are already familiar with such mind games.) As Naoko finds out more about her great-uncle who was one of the last kamikaze airmen and discovers his secret diary (written in French to complicate matters), she bundles these in with her notebook. ‘Ruth’ and the reader read the grim truth about the sadistic training and exploitation of the young men the failing Japanese military abused in this way. However, if the reader thinks that’s the most harrowing part of the story, be warned, the emotional turmoil moves up several gears as Naoko’s world collapses and, one can argue, in consequence, so is ‘Ruth’s’ put at great risk.

Although ‘Ruth’ searches and researches trying to trace the teenage diarist, she only manages to circle in closer and closer but they never meet. While the diarist tries to imagine the person who may eventually read her writings, the ‘author’ tries to picture the diarist as she must be now, if she is still alive; a woman in her twenties living somewhere, maybe Tokyo, maybe Paris.

And finally, the most important point: the quality of the writing and the pacing of the unfolding story are superb and it is easy to see how the book made the Man Booker prize short list this year. I will give this novel a rating of 8 out of ten and heartily recommend it to book reading groups.

The post Booker Prize short-listed Ruth Ozeki tells “A Tale for the Time Being” and does so very well appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 24, 2013

Video blog – review of The Luminaries, by Eleanor Catton

This is a video adaptation of my recent text blog, reviewing the 2013 Man Booker prize-winning novel.

The post Video blog – review of The Luminaries, by Eleanor Catton appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 13, 2013

Let’s Talk About Middlemarch – Michael Johnston’s first video blog

My Youtube Channel has now been launched and below is my first video blog – an introduction to Middlemarch, by George Eliot, outlining the three main groups of characters whose narrative strands run through the story.

I also make reference to the current, highly praised, ‘Middlemarch Trilogy’ of plays being performed at the Orange Tree Theatre, at Richmond, Surrey, between October 2013 and January 2014. I blogged about these plays recently.

I hope you enjoy this new, additional blog format. Please comment below, along with any suggestions for future video or written blog topics.

The post Let’s Talk About Middlemarch – Michael Johnston’s first video blog appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 12, 2013

Rustication by Charles Palliser: Victorian pastiche that is even better than the genuine article.

Ever since I read The Quincunx I have been hooked on the novels of Charles Palliser. He has a gift for writing complex Victorian-style mysteries that can stand comparison with those past masters Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins. Certain themes run through Betrayals (as funny as it is mysterious) and The Unburied and turn up again in Rustication, Palliser’s latest novel for which we have had to wait almost as long as it takes to take for a case to go through Chancery! (He also wrote, and I read, a novel set in the twentieth century, The Sensationalist: it doesn’t belong in the canon.)

Palliser’s plots are so complex the reader must pay close attention. Every word counts; the Preface or Foreword must be studied as well as the Afterword; even the Appendix and the List of Names or Characters need to be read and enjoyed. The choice of names for the characters rivals Dickens’s gift in this regard. If there is a map or a diagram, it means something. In Rustication (whose arrival I alerted you to in an earlier blog) every word of the handwritten anonymous letters should be looked at with care. These are mysteries and, to an extent, they are unravelled but the reader is still left, at the end, with questions that will nag away and never be answered. In other words, I loved this book.

Palliser takes readers back to the misty, rainy, snow-covered, and cold imagined town of Thurchester, which at a guess, might be somewhere in East Anglia, the location for The Unburied, but there are no characters who stray across into the new novel. Instead, we have the young narrator, Richard Shenstone who, in the winter of 1863, has been ‘rusticated’ from his Cambridge college for reasons that are teased out of him over the course of the book. He returns to an isolated house on the edge of the sea marshes to which his mother and sister have been literally rusticated following the death of his clerical father. No one in the book has an unblemished character and some are significantly more blemished than others.

Palliser takes readers back to the misty, rainy, snow-covered, and cold imagined town of Thurchester, which at a guess, might be somewhere in East Anglia, the location for The Unburied, but there are no characters who stray across into the new novel. Instead, we have the young narrator, Richard Shenstone who, in the winter of 1863, has been ‘rusticated’ from his Cambridge college for reasons that are teased out of him over the course of the book. He returns to an isolated house on the edge of the sea marshes to which his mother and sister have been literally rusticated following the death of his clerical father. No one in the book has an unblemished character and some are significantly more blemished than others.

Shenstone, of course, keeps a journal which someone (whose initials are CP) has recently uncovered in the County Records Office. An earlier ‘someone’ has gathered up the alarming anonymous letters and has pasted them into the journal at the point in Shenstone’s narrative where they were delivered to their appalled recipients. As young Richard relates his efforts to solve the whole mystery, he advances theory after theory, solution after solution, only to have each one confounded by a new turn of events and further revelations. His own reliability is not helped by his habit of smoking opium and his teenage sexuality that get in the way of clear-headed analysis. As the net closes, Shenstone suddenly finds that he is still inside it, along with his sister and his mother.

My hope is that if you have not read any of his other novels, Rustication will encourage you to seek them out. I hope too that Palliser has at least one more novel to come. I would recommend it, even unread! Meanwhile, I will give this one 8 out of 10.

The post Rustication by Charles Palliser: Victorian pastiche that is even better than the genuine article. appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 4, 2013

Man Booker Prize book reading groups have a treat in store: The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton

Fascinating for me to pick up the 2013 Man Booker Prize winning novel, The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton, just after putting down the very Victorian Middlemarch. The new book is 47 pages longer, so you might argue I was in training for it. Catton, a Canadian born and educated writer now living in New Zealand has set her book there in Victorian times, 1865/66 when men of all classes came to the country intent on discovering a ‘homeward bounder’; a strike that would earn them enough to go back home to a life of ease and comfort. And where there are fortunes to be made, there are others willing to relieve the diggers of their bonanzas by fair means or foul.

Fascinating for me to pick up the 2013 Man Booker Prize winning novel, The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton, just after putting down the very Victorian Middlemarch. The new book is 47 pages longer, so you might argue I was in training for it. Catton, a Canadian born and educated writer now living in New Zealand has set her book there in Victorian times, 1865/66 when men of all classes came to the country intent on discovering a ‘homeward bounder’; a strike that would earn them enough to go back home to a life of ease and comfort. And where there are fortunes to be made, there are others willing to relieve the diggers of their bonanzas by fair means or foul.

The first time I walloped through the book, desperately trying to pick the winner from the short list before it was announced (and getting it wrong), I was somewhat put off by the structure and the use of astrology charts at the beginning of each section of the book. Like the phases of the moon, the parts (chapters) start with a full 360 pages and then ‘wane’ to a single page. Reading this time with more care and attention, I am still not drawn into the astrological decoration but I have been completely overwhelmed by the quality of Catton’s plotting, structure and language of the story; English, with occasional New Zealand Maori and Cantonese. With the discursive abilities of George Eliot, or possibly a better comparison would be Wilkie Collins, Catton’s first chapter, ‘A Sphere within a sphere’, develops the events of a single day, 27 January 1866, in the gold rush port of Hokitika on the western, Tasman Sea coast of South Island where, to this day, there is a shipwreck memorial testifying to the difficulties of crossing the bar in stormy weather, where one can stand on Gibson Quay or walk up Revell-street. The story then is physically grounded in reality despite its astrologic surface decoration.

In this first chapter, we interrupt the twelve luminaries, Hokitika residents, holding a private meeting in the Crown Hotel when Walter Moody, a Scottish lawyer, ferried ashore that very day after a stormy and frightening passage on the Godspeed that will itself be wrecked on the bar, unwittingly enters and puts a momentary freeze on their conversation until one of them talks with Moody and the others are then persuaded to reveal their separate stories for appraisal and comment by this thirteenth person in the room. All of them seem to have some relationship with an unfortunate whore, Anna Weatherall, who has been found on the street unconscious and incapable, probably due to the effects of opium, and a former digger turned timber merchant, Crosbie Wells, who has just been found dead in his cabin with a fortune in retorted gold hidden away. With great skill, Catton manages both to thicken the plot and bring out the details that enable the reader to know what they need to know about all twenty characters in the book.

Subsequent chapters move backwards and forwards between dates in 1865 and 1866 (intriguingly, the book ends before it begins) and slowly peel layers of the onion to reveal more of the truth, the half-truths, and the downright lies they all tell and something of their motives and motivations. Some ‘facts’ are, in the end, never explained and the reader will need to formulate his or her own explanation or rationalisation of events, such as the death in a closed paddy wagon of one of the characters. When the (gold) dust settles, I think we have a wonderful book here, with much authentic period detail woven among sparkling language and literary ingenuity, that it is not hard to see how The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton won the Man Booker prize for 2013.

The post Man Booker Prize book reading groups have a treat in store: The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

November 1, 2013

Theatre review: The Middlemarch Trilogy at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond

There is always a period of nervous tension when one goes to see an adaptation; especially of a well-loved classic novel like Middlemarch which is being staged over the next three months at the ever-enterprising Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond. Will the adapted version convey the spirit of the original, even after making allowances for the different medium? We can all relax. Geoffrey Beevers’s Middlemarch Trilogy has got off to a tremendous start with the current production of ‘Dorothea’s Story’.

Readers of my earlier blog on the novel will recall that the Middlemarch story has three main strands which interweave throughout the book and are resolved, one way or another very near the end of George Eliot’s long book; (yet not quite as long as the Man Booker Prize winner, The Luminaries which I am currently re-reading to see why I did not pick it myself!) Beevers has written three plays; ‘Dorothea’s Story’, ‘The Doctor’s Story’ and ‘Fred and Mary’. The first is currently being performed and will be joined by the second in the middle of November and the third at the beginning of December. They will play in repertory until the end of January. A limited number of all-day three-play marathons are scheduled over the Christmas holiday period. Book now to avoid a major disappointment!

The adapter has several problems with Middlemarch. First, it is a very long book and much of the narrative shows up Eliot’s own wicked sense of humour, her acute and astute powers of observation and her understanding of human nature. Second, within the space of a novel, the writer can explore different story lines, switching from one to another as the development of the whole progresses. By contrast, the playwright must condense, boiling off the vapour but retaining all the essences; must show rather than tell to avoid making the exposition stick out awkwardly from the developing narrative. Third, s/he must make a drama out of it rather than simply a recital of choice extracts. (I noted especially how Beevers delays telling the audience what jealous Casaubon had done until the most dramatic moment to do so.) On the strength of ‘Dorothea’s Story’, Geoffrey Beevers has succeeded in all three areas.

The actors are generally all on stage, sitting at the four corners of the Orange Tree’s theatre-in-the-square. Thus the pace of the action is sustained as scene rapidly follows scene. Necessary but very brief exposition is spoken by actors from their corners or as they shift the very minimal stage props and, by using almost entirely Eliot’s witty prose and apposite comments, the audience not only follows the story but, right from the start, laughs out loud at the novelist’s ironic sense of humour. The humour of the book has been perfectly captured: Middlemarch may be long but it is never dull. Solving the complexity of the novel’s story line has been splendidly achieved by the device of making it into three plays. Each can be seen on its own and, if necessary, in any order but the ideal sequence would be Dorothea, the Doctor, then Fred & Mary. Some of the scenes will appear to be repeated in later plays but are witnessed from a different standpoint provoking the attentive Orange Tree audience to notice these subtle changes of perspective.

The actors are served by an excellent script and fast-paced direction and the adaptor is served by a company of enthusiastic actors who double many roles. Beevers has deliberately given them contrasting roles to play, such as the dry-as-dust Rector of Lowick and the lover-of-life vicar, Mr Featherstone. Do book soon for this feast of English provincial fun. Call the Orange Tree Box Office today!

The post Theatre review: The Middlemarch Trilogy at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

October 17, 2013

For ‘classic Victorian novel’ book reading groups: it’s time to revisit ‘Middlemarch’

Last night, I put down my well-thumbed copy of that classic, that almost archetypal Victorian novel, Middlemarch by George Eliot. Though some may have others as their favourite Victorian novelist, and Dickens, Trollope and even Henry James must run her close, Eliot has a quality of writing that sets her apart. Going even further, I believe Middlemarch is the best of her novels. And yet it was only twenty years ago I first read this story of English provincial life at a time when Reform was the political battlefield, rival theories of evolution divided the people and the railways were cutting swathes through the countryside (and the cities): a period Eliot knew from personal experiences she could draw on as she wrote her book in the early 1870s.

Last night, I put down my well-thumbed copy of that classic, that almost archetypal Victorian novel, Middlemarch by George Eliot. Though some may have others as their favourite Victorian novelist, and Dickens, Trollope and even Henry James must run her close, Eliot has a quality of writing that sets her apart. Going even further, I believe Middlemarch is the best of her novels. And yet it was only twenty years ago I first read this story of English provincial life at a time when Reform was the political battlefield, rival theories of evolution divided the people and the railways were cutting swathes through the countryside (and the cities): a period Eliot knew from personal experiences she could draw on as she wrote her book in the early 1870s.

Society then was a set of rules where there was a place for everyone and everyone was put in  their place by those even one step up the hierarchical ladder. Money, then as now, could buy you one or two steps up the ladder but those higher up never forgot where anyone lower down had started off. The sins of the fathers or the mothers incurred a penalty of being relegated one or two steps down. These truths found a set of characters who work out their relationships and their overlapping destinies over 785 pages, almost as many as the Man Booker Prize winner this year. Eliot writes with wit, irony and erudition and unveils her story and unravels its three plot strands at the pace that suited the taste of the readership of the 1870s and its fondness for three-volume ‘baggy monsters’.

their place by those even one step up the hierarchical ladder. Money, then as now, could buy you one or two steps up the ladder but those higher up never forgot where anyone lower down had started off. The sins of the fathers or the mothers incurred a penalty of being relegated one or two steps down. These truths found a set of characters who work out their relationships and their overlapping destinies over 785 pages, almost as many as the Man Booker Prize winner this year. Eliot writes with wit, irony and erudition and unveils her story and unravels its three plot strands at the pace that suited the taste of the readership of the 1870s and its fondness for three-volume ‘baggy monsters’.

Who’s who in Middlemarch

Saintly but naïve Dorothea [BBC photo] and her sister live with their well-to-do, well-read but little-remembered, uncle Mr Brooke. They are among the novel’s representatives of the landed classes. Dorothea aspires to do good for others and to learn, while her sister Celia just wants a rich husband. While the local baronet, Sir James Cheetham trails his coat in front of her and builds better farm cottages to prove his ability to do good, Dorothea allows herself to become convinced that the dry stick and Rector of Lowick, Mr Casaubon; decades her senior, who has spent his life researching the more obscure byways of myths, seeking to track them to a common origin; is someone she could look up to, learn from and assist in his great work. Reader, she married him!

Saintly but naïve Dorothea [BBC photo] and her sister live with their well-to-do, well-read but little-remembered, uncle Mr Brooke. They are among the novel’s representatives of the landed classes. Dorothea aspires to do good for others and to learn, while her sister Celia just wants a rich husband. While the local baronet, Sir James Cheetham trails his coat in front of her and builds better farm cottages to prove his ability to do good, Dorothea allows herself to become convinced that the dry stick and Rector of Lowick, Mr Casaubon; decades her senior, who has spent his life researching the more obscure byways of myths, seeking to track them to a common origin; is someone she could look up to, learn from and assist in his great work. Reader, she married him!

It turns out Casaubon has a much younger cousin, grandson of a Casaubon who married beneath her and that the Rector has been supporting him financially in his studies.  Dorothea encounters him first in Lowick as she walks with her fiancé then later in Rome on her wedding journey where Casaubon [BBC photo] takes his taper into the Vatican’s libraries rather than taking his candle up to the marriage bed. Cousin Will Ladislaw is certainly captivated by Dorothea, and she forms an innocent liking for her lively cousin-in-law, but Casaubon takes a dim view and eventually inserts a codicil in his will that will disinherit Dorothea if she ever marries Will. He then dies, Dorothea inherits and, over the rest of the book we watch and wonder if she and Will can ever get together, despite society’s disapproval and the will’s financial penalty. Don’t peek but the answer is on page 762.

Dorothea encounters him first in Lowick as she walks with her fiancé then later in Rome on her wedding journey where Casaubon [BBC photo] takes his taper into the Vatican’s libraries rather than taking his candle up to the marriage bed. Cousin Will Ladislaw is certainly captivated by Dorothea, and she forms an innocent liking for her lively cousin-in-law, but Casaubon takes a dim view and eventually inserts a codicil in his will that will disinherit Dorothea if she ever marries Will. He then dies, Dorothea inherits and, over the rest of the book we watch and wonder if she and Will can ever get together, despite society’s disapproval and the will’s financial penalty. Don’t peek but the answer is on page 762.

A village incomer, full of new, scientific ideas and a great ambition to do well by his fellow men is Dr Tertius Lydgate, representing the middle classes. He buys a practice in Middlemarch and plans to continue his medical and scientific researches funded by his  income from treating patients but not from selling them their medicines which other doctors do. Marriage is certainly on his agenda but not much higher than Any Other Business, until he is noted and coveted by Rosamond Vincy, a pretty, empty-headed noodle who cannot conceive that others would not want to do things her way and is so convinced of her rightness that, many a time and oft, she simply does the opposite of what she has promised. Reader, he married her!

income from treating patients but not from selling them their medicines which other doctors do. Marriage is certainly on his agenda but not much higher than Any Other Business, until he is noted and coveted by Rosamond Vincy, a pretty, empty-headed noodle who cannot conceive that others would not want to do things her way and is so convinced of her rightness that, many a time and oft, she simply does the opposite of what she has promised. Reader, he married her!

However, Lydgate’s patients are often slow to pay and he is shunned by other local practitioners, not least when Bible-punching, wealthy banker Bulstrode appoints him, but with no salary, as medical superintendent of the hospital he has financed. It wouldn’t be a Victorian novel if there were no skeletons in most characters’ cupboards and Bulstrode has his share. By becoming obliged and later indebted to Bulstrode while trying to please and placate Rosamond, Tertius is drawn inexorably into the banker’s problems. Rosamond, quite deliberately yet without telling Lydgate, thwarts her husband’s plans to move out of their expensive house into a more economical one, pushing him ever nearer financial and social ruin. How the doctor’s story ends is also not revealed until very near the end of the novel.

The real workers and hard grafters are the Garth family. Caleb Garth is a fairly representative businessman, a successful agricultural manager, surveyor and engineer, yet who cannot always manage his own finances well. He supports his family and is well liked in the community and loved by his wife and children including homely daughter Mary. Rosamond’s brother Fred Vincy is a young man who has never had to earn a living and who is destined by his mill-owning father for the church, since it seems he would be no use in the business. Fred doesn’t want to be a minister but doesn’t know what he really wants except  that for as long as he can remember he has wanted to marry Mary. The Garths are fond of him and Caleb foolishly signs a bill for Fred. When Fred’s horse-dealing plan comes unstuck it is Caleb and his family who have to pay up. The story of Fred and Mary, its romantic ups and downs, is the third main strand of Middlemarch. Fred thought he was going to inherit an estate from a curmudgeonly relative until the relative died and left it elsewhere. The funeral and the will reading is one of the many great set pieces of the novel, full of wicked irony and shrewd observation of life. Thus, Fred has to struggle to find himself and make a respectable career sufficient to be able at last to propose to Mary. You will have to read the book to find out if she marries him!

that for as long as he can remember he has wanted to marry Mary. The Garths are fond of him and Caleb foolishly signs a bill for Fred. When Fred’s horse-dealing plan comes unstuck it is Caleb and his family who have to pay up. The story of Fred and Mary, its romantic ups and downs, is the third main strand of Middlemarch. Fred thought he was going to inherit an estate from a curmudgeonly relative until the relative died and left it elsewhere. The funeral and the will reading is one of the many great set pieces of the novel, full of wicked irony and shrewd observation of life. Thus, Fred has to struggle to find himself and make a respectable career sufficient to be able at last to propose to Mary. You will have to read the book to find out if she marries him!

Now go and see the plays

As I have mentioned in another blog, the actor-director Geoffrey Beevers has adapted the novel into a trilogy of plays – ‘Dorothea’s Story’, ‘The Doctor’s Story’ and ‘Fred and Mary’ – which are going into repertory at the renowned theatre-in-the-round, the Orange Tree in Richmond-upon-Thames. I have my tickets bought for all three. Click through here to the Orange Tree Theatre Box Office. My illustration of Fred and Mary above comes by courtesy of the Orange Tree Theatre.

The post For ‘classic Victorian novel’ book reading groups: it’s time to revisit ‘Middlemarch’ appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

For ‘classic Victorian novel’ book-reading groups: it’s time to revisit ‘Middlemarch’

Last night, I put down my well-thumbed copy of that classic, that almost archetypal Victorian novel, Middlemarch by George Eliot. Though some may have others as their favourite Victorian novelist, and Dickens, Trollope and even Henry James must run her close, Eliot has a quality of writing that sets her apart. Going even further, I believe Middlemarch is the best of her novels. And yet it was only twenty years ago I first read this story of English provincial life at a time when Reform was the political battlefield, rival theories of evolution divided the people and the railways were cutting swathes through the countryside (and the cities): a period Eliot knew from personal experiences she could draw on as she wrote her book in the early 1870s.

Last night, I put down my well-thumbed copy of that classic, that almost archetypal Victorian novel, Middlemarch by George Eliot. Though some may have others as their favourite Victorian novelist, and Dickens, Trollope and even Henry James must run her close, Eliot has a quality of writing that sets her apart. Going even further, I believe Middlemarch is the best of her novels. And yet it was only twenty years ago I first read this story of English provincial life at a time when Reform was the political battlefield, rival theories of evolution divided the people and the railways were cutting swathes through the countryside (and the cities): a period Eliot knew from personal experiences she could draw on as she wrote her book in the early 1870s.

Society then was a set of rules where there was a place for everyone and everyone was put in  their place by those even one step up the hierarchical ladder. Money, then as now, could buy you one or two steps up the ladder but those higher up never forgot where anyone lower down had started off. The sins of the fathers or the mothers incurred a penalty of being relegated one or two steps down. These truths found a set of characters who work out their relationships and their overlapping destinies over 785 pages, almost as many as the Man Booker Prize winner this year. Eliot writes with wit, irony and erudition and unveils her story and unravels its three plot strands at the pace that suited the taste of the readership of the 1870s and its fondness for three-volume ‘baggy monsters’.

their place by those even one step up the hierarchical ladder. Money, then as now, could buy you one or two steps up the ladder but those higher up never forgot where anyone lower down had started off. The sins of the fathers or the mothers incurred a penalty of being relegated one or two steps down. These truths found a set of characters who work out their relationships and their overlapping destinies over 785 pages, almost as many as the Man Booker Prize winner this year. Eliot writes with wit, irony and erudition and unveils her story and unravels its three plot strands at the pace that suited the taste of the readership of the 1870s and its fondness for three-volume ‘baggy monsters’.

Who’s who in Middlemarch.

Saintly but naïve Dorothea [BBC photo] and her sister live with their well-to-do, well-read but little-remembered, uncle Mr Brooke. They are among the novel’s representatives of the landed classes. Dorothea aspires to do good for others and to learn, while her sister Celia just wants a rich husband. While the local baronet, Sir James Cheetham trails his coat in front of her and builds better farm cottages to prove his ability to do good, Dorothea allows herself to become convinced that the dry stick and Rector of Lowick, Mr Casaubon; decades her senior, who has spent his life researching the more obscure byways of myths, seeking to track them to a common origin; is someone she could look up to, learn from and assist in his great work. Reader, she married him!

Saintly but naïve Dorothea [BBC photo] and her sister live with their well-to-do, well-read but little-remembered, uncle Mr Brooke. They are among the novel’s representatives of the landed classes. Dorothea aspires to do good for others and to learn, while her sister Celia just wants a rich husband. While the local baronet, Sir James Cheetham trails his coat in front of her and builds better farm cottages to prove his ability to do good, Dorothea allows herself to become convinced that the dry stick and Rector of Lowick, Mr Casaubon; decades her senior, who has spent his life researching the more obscure byways of myths, seeking to track them to a common origin; is someone she could look up to, learn from and assist in his great work. Reader, she married him!

It turns out Casaubon has a much younger cousin, grandson of a Casaubon who married beneath her and that the Rector has been supporting him financially in his studies.  Dorothea encounters him first in Lowick as she walks with her fiancé then later in Rome on her wedding journey where Casaubon [BBC photo] takes his taper into the Vatican’s libraries rather than taking his candle up to the marriage bed. Cousin Will Ladislaw is certainly captivated by Dorothea, and she forms an innocent liking for her lively cousin-in-law, but Casaubon takes a dim view and eventually inserts a codicil in his will that will disinherit Dorothea if she ever marries Will. He then dies, Dorothea inherits and, over the rest of the book we watch and wonder if she and Will can ever get together, despite society’s disapproval and the will’s financial penalty. Don’t peek but the answer is on page 762.

Dorothea encounters him first in Lowick as she walks with her fiancé then later in Rome on her wedding journey where Casaubon [BBC photo] takes his taper into the Vatican’s libraries rather than taking his candle up to the marriage bed. Cousin Will Ladislaw is certainly captivated by Dorothea, and she forms an innocent liking for her lively cousin-in-law, but Casaubon takes a dim view and eventually inserts a codicil in his will that will disinherit Dorothea if she ever marries Will. He then dies, Dorothea inherits and, over the rest of the book we watch and wonder if she and Will can ever get together, despite society’s disapproval and the will’s financial penalty. Don’t peek but the answer is on page 762.

A village incomer, full of new, scientific ideas and a great ambition to do well by his fellow men is Dr Tertius Lydgate, representing the middle classes. He buys a practice in Middlemarch and plans to continue his medical and scientific researches funded by his  income from treating patients but not from selling them their medicines which other doctors do. Marriage is certainly on his agenda but not much higher than Any Other Business, until he is noted and coveted by Rosamond Vincy, a pretty, empty-headed noodle who cannot conceive that others would not want to do things her way and is so convinced of her rightness that, many a time and oft, she simply does the opposite of what she has promised. Reader, she married him!

income from treating patients but not from selling them their medicines which other doctors do. Marriage is certainly on his agenda but not much higher than Any Other Business, until he is noted and coveted by Rosamond Vincy, a pretty, empty-headed noodle who cannot conceive that others would not want to do things her way and is so convinced of her rightness that, many a time and oft, she simply does the opposite of what she has promised. Reader, she married him!

However, Lydgate’s patients are often slow to pay and he is shunned by other local practitioners, not least when Bible-punching, wealthy banker Bulstrode appoints him, but with no salary, as medical superintendent of the hospital he has financed. It wouldn’t be a Victorian novel if there were no skeletons in most characters’ cupboards and Bulstrode has his share. By becoming obliged and later indebted to Bulstrode while trying to please and placate Rosamond, Tertius is drawn inexorably into the banker’s problems. Rosamond, quite deliberately yet without telling Lydgate, thwarts her husband’s plans to move out of their expensive house into a more economical one, pushing him ever nearer financial and social ruin. How the doctor’s story ends is also not revealed until very near the end of the novel.

The real workers and hard grafters are the Garth family. Caleb Garth is a fairly representative businessman, an agricultural manager, surveyor and engineer, who cannot always manage his own finances well. He supports his family and is well liked in the community and loved by his wife and children including homely daughter Mary. Rosamond’s brother Fred Vincy is a young man who has never had to earn a living and who is destined by his mill-owning father for the church, since it seems he would be no use in the business. Fred doesn’t want to be a minister but doesn’t know what he really wants except  that for as long as he can remember he has wanted to marry Mary. The Garths are fond of him and Caleb foolishly signs a bill for Fred. When Fred’s horse-dealing plan comes unstuck it is Caleb and his family who have to pay up. The story of Fred and Mary, its romantic ups and downs, is the third main strand of Middlemarch. Fred thought he was going to inherit an estate from a curmudgeonly relative until the relative died and left it elsewhere. The funeral and the will reading is one of the many great set pieces of the novel, full of wicked irony and shrewd observation of life. Thus, Fred has to struggle to find himself and make a respectable career sufficient to be able at last to propose to Mary. You will have to read the book to find out if she marries him!

that for as long as he can remember he has wanted to marry Mary. The Garths are fond of him and Caleb foolishly signs a bill for Fred. When Fred’s horse-dealing plan comes unstuck it is Caleb and his family who have to pay up. The story of Fred and Mary, its romantic ups and downs, is the third main strand of Middlemarch. Fred thought he was going to inherit an estate from a curmudgeonly relative until the relative died and left it elsewhere. The funeral and the will reading is one of the many great set pieces of the novel, full of wicked irony and shrewd observation of life. Thus, Fred has to struggle to find himself and make a respectable career sufficient to be able at last to propose to Mary. You will have to read the book to find out if she marries him!

Now go and see the plays.

As I have mentioned in another blog, the actor-director Geoffrey Beevers has adapted the novel into a trilogy of plays – ‘Dorothea’s Story’, ‘The Doctor’s Story’ and ‘Fred and Mary’ – which are going into repertory at the renowned theatre-in-the-round, the Orange Tree in Richmond-upon-Thames. I have my tickets bought for all three. Click through here to the Orange Tree Theatre Box Office. My illustration of Fred and Mary above comes by courtesy of the Orange Tree Theatre.

The post For ‘classic Victorian novel’ book-reading groups: it’s time to revisit ‘Middlemarch’ appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

October 15, 2013

Man Booker Prize personal prediction: one of six; but which?

As I write about my personal choice for the Man Booker Prize in 2013, bookmakers, who react to the amount of money placed on each contender, have shortened the odds for two books: Harvest by Jim Crace and The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton (the youngest ever contender) with veteran Colm Tóbín’s The Testament of Mary lying third. In truth, though I have no money riding on the outcome, that is how I would rate the shortlist.

My problem with the Tóbín is simply its length: this isn’t a novel, being just too short. It is a beautiful writing exercise but I do not warm to the subject and feel short-changed by the length. Crace did better with his earlier novel Quarantine (which is the French word for forty days) which told the story of the forty days and nights spent by Jesus in the wilderness.

My problem with Catton is certainly not that, with over 800 pages, it is too long: no really good book can ever be too long. However, I did become weary of the structure where the first chapter takes up half the book and subsequent chapters are half the length of the preceding one. The first half is a great read and Catton deserves a loyal following of book buyers to support a very promising career but if (blissful thought) I had to read over a hundred novels to select a long and then a short list, I might not have picked out The Luminaries. Some readers’ polls put it out in front, however.

So, I am going for Harvest and for a writer who could well have won this prize for some of his earlier work. The mysterious village where the action takes place over a week seems to be mediaeval but some have even suggested it is post-apocalyptic. Who knows? The narrator is a one-time incomer of twelve years standing (in other words, despite marrying into the gene pool, still something of an outsider). It is barley harvest time when calamity strikes, and strikes again. Crace uses words like a true craftsman and you find odd ones that may not appear in the dictionary that create a sense of distance from the present day. He builds a crystal clear picture touching all our senses, not least smell, but occasionally lets smoke from fires drift over the plot to keep the reader on the qui vive. I hope Crace wins and that this prompts him to go on writing.

So, I am going for Harvest and for a writer who could well have won this prize for some of his earlier work. The mysterious village where the action takes place over a week seems to be mediaeval but some have even suggested it is post-apocalyptic. Who knows? The narrator is a one-time incomer of twelve years standing (in other words, despite marrying into the gene pool, still something of an outsider). It is barley harvest time when calamity strikes, and strikes again. Crace uses words like a true craftsman and you find odd ones that may not appear in the dictionary that create a sense of distance from the present day. He builds a crystal clear picture touching all our senses, not least smell, but occasionally lets smoke from fires drift over the plot to keep the reader on the qui vive. I hope Crace wins and that this prompts him to go on writing.

Now then, I must get back to work on a contender for next year!

The post Man Booker Prize personal prediction: one of six; but which? appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

October 10, 2013

Three different book clubs for hungry readers who like an element of surprise!

With so many books on my shelves that are either still to read or which I very much want to read again – right now it’s Middlemarch –, what do I need with not one or two but three book clubs that will be sending me still more books over the next twelve months? And yet, for their different reasons, they have all appealed to me. At least, all of them will be sending me physical books and I can continue my one-man campaign to boycott e-book readers. Admittedly, that’s not quite consistent with my own novel, Rembrandt Sings, being available across all e-platforms but, as the closing line of Some Like it Hot says, “Nobody’s perfect.”

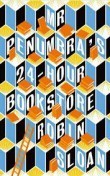

In order of joining, I am a member of the Litro Book Club which sends me a new book each quarter written by new and emerging writers; plus 10 issues of a C5 sized literary magazine, each issue full of news and a themed set of new writing, each month different. I almost never read magazines and newspapers since it takes me away too long from reading and writing fiction but I am quite hooked on the Litro mag. The last book they sent me took me completely by surprise. Many of the things about Mr Penumbra’s 24-hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan might have put me off if I’d had to choose between this and something else in a bookshop. However, I was very much taken by Sloan’s first full-length novel and wrote an enthusiastic book review blog about it. So; from Litro four books a year, not chosen by me but by them. Find them at www.litro.co.uk

In order of joining, I am a member of the Litro Book Club which sends me a new book each quarter written by new and emerging writers; plus 10 issues of a C5 sized literary magazine, each issue full of news and a themed set of new writing, each month different. I almost never read magazines and newspapers since it takes me away too long from reading and writing fiction but I am quite hooked on the Litro mag. The last book they sent me took me completely by surprise. Many of the things about Mr Penumbra’s 24-hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan might have put me off if I’d had to choose between this and something else in a bookshop. However, I was very much taken by Sloan’s first full-length novel and wrote an enthusiastic book review blog about it. So; from Litro four books a year, not chosen by me but by them. Find them at www.litro.co.uk

About the publisher And Other Stories I need to declare an interest. By taking out my subscription to books still to appear, which was very much the way to promote and finance books in earlier centuries, I find my name, in alphabetic order of given names, like the Icelandic Phone Book (a great read!) in the back of the book which is more than I do when I scan the index of political memoirs. Here’s what Litro has to say about themselves on their website www.andotherstories.org

And Other Stories has been set up as a Community Interest Company (CIC, pronounced ‘kick’ not ‘sick’). This means we are a not-for-private-profit company. What gives us a ‘CIC’? (Couldn’t resist!) We make our decisions based on what we think is good writing and a good way of working. This sets us apart from shareholder-driven publishing companies where all decisions are ultimately about increasing profits. Of course, in order to be able to continue our work in the long-term, we certainly can’t lose money … We are a literary publishing house that works on the principle that great new books will be heard about and read thanks to the combined intelligence of a number of people: editors, readers, translators, critics, literary promoters and academics. We hope we can host such collaboration.

The mention of translators is important as many of the books are first-rate translations that  are, through the subscription list, given access to the wider anglophone audience. They have reading groups in several countries to discuss works from other languages and assist in the selection of books and they claim that they are also able to pay translators a decent reward for their work which is by no means the general condition. I have read with pleasure and blogged about All Dogs are Blue

by Rodrigo de Sousa Leão

and

Quesadillas

by Juan Pablo Villalobos. Subscription levels vary but I went for the full whack, contracting for six books a year. So, six books from & Other Stories; again, not chosen by me!

are, through the subscription list, given access to the wider anglophone audience. They have reading groups in several countries to discuss works from other languages and assist in the selection of books and they claim that they are also able to pay translators a decent reward for their work which is by no means the general condition. I have read with pleasure and blogged about All Dogs are Blue

by Rodrigo de Sousa Leão

and

Quesadillas

by Juan Pablo Villalobos. Subscription levels vary but I went for the full whack, contracting for six books a year. So, six books from & Other Stories; again, not chosen by me!

Finally, on a whim, I have joined what could be a total waste of time (judging by the first book they have sent me which I will be giving to Oxfam unless any reader wants Stuck Up! 100 Objects inserted and ingested in places where they shouldn’t be , with loads of X-ray illustrations. (Contact me if you really must have this!) The Random Book Club is run by one of the UK’s biggest second-hand bookshops in Wigtown (Dumfries & Galloway). I must go there sometime and compare it with the Barter Books in Alnwick. Anyway, for £59 a year, they will send me a dozen completely assorted and varied books across all the genres including non-fiction. I will let you know how I get on but I leave you with one of their postcards and their website address, www.randombookclub.co.uk

The post Three different book clubs for hungry readers who like an element of surprise! appeared first on Michael Johnston's blog/website (akanos.co.uk).

Michael Johnston's Blog

- Michael Johnston's profile

- 4 followers