Jose Angel Araguz's Blog, page 26

November 17, 2017

raining with Martorell & Pizarnik

Earlier this week, I had the opportunity to do a small reading at Linfield College’s Miller Fine Arts Center. The Linfield Gallery is in its last week of hosting Antonio Martorell’s solo exhibit “Rain/Lluvia.” In talking about the origins of the exhibit, Martorell told Linfield Gallery: “When the opportunity came my way to bring an exhibition to Oregon, a place that I had never visited before, I candidly asked: ‘¿Qué pasa en Oregon?’ (What happens in Oregon?) I received an equally candid answer: ‘It rains every day.’”

[image error]In this spirit, I selected poems from my own work that dealt with rain in one way or another, in Oregon and rains elsewhere as well. Along with “Thinking About the Poet Larry Levis One Afternoon in Late May” by Charles Wright, I read two poems by Alejandra Pizarnik, both in the original Spanish and in English translations I did specifically for this reading. I share both poems and translations below as well as a clip of my reading of “L’obscurité des eaux.” Pizarnik’s work felt appropriate for the space as it interrogates the ways meaning is made, engaging with the ephemeral nature of words.

Rain works with a similar ephemerality. There is only something we can call rain when water is in motion between sky and earth; similarly, poetry lives in the space between set words and the motion of reading.

Special thanks to Brian Winkenweder for the invitation to read and to all those who attended!

*

Despedida – Alejandra Pizarnik

Mata su luz un fuego abandonado.

Sube su canto un pájaro enamorado.

Tantas criaturas ávidas en mi silencio

y esta pequeña lluvia que me acompaña.

*

Farewell

— translated by José Angel Araguz

An abandoned fire kills its light.

A bird in love raises its song.

So many avid creatures in my silence

and this little rain that accompanies me.

[image error]

L’obscurité des eaux – Alejandra Pizarnik

Escucho resonar el agua que cae en mi sueño.

Las palabras caen como el agua yo caigo. Dibujo

en mis ojos la forma de mis ojos, nado en mis

aguas, me digo mis silencios. Toda la noche

espero que mi lenguaje logre configurarme. Y

pienso en el viento que viene a mí, permanece

en mí. Toda la noche he caminado bajo la lluvia

desconocida. A mí me han dado un silencio

pleno de formas y visiones (dices). Y corres desolada

como el único pájaro en el viento.

*

The darkness of the waters

— translated by José Angel Araguz

I hear the water that falls in my dream resound.

The words fall like water I fall. I draw

in my eyes the shape of my eyes, I swim in my

waters, I tell myself my silences. All night

I hope my language manages to configure me. And

I think about the wind that comes to me, remains

in me. All night I walked in the unknown rain.

I have been given a silence

full of forms and visions (you say). And you run desolate

as the only bird in the wind.

*

photo credit: Linfield Gallery

November 10, 2017

poetryamano project: february 2017

This week I’m sharing the second installment archiving my Instagram poetry project entitled @poetryamano (poetry by hand). This account focuses on sharing poems written by hand, either in longhand or more experimental forms such as erasures/blackout poems and found poems.

I’d like to give a quick thank you to Kenyatta JP García for giving @poetryamano a shout out here.

Below are the highlights from February 2017. Be sure to check out the first installment.

Stay tuned next week for more of the usual Influence happenings. For now, enjoy these forays into variations on the short lyric!

[image error]

In February, I had been coming back to rain and mirrors in my free writes. I always worry about retreading, but then some words and images are like worry stones, no?

[image error]

Translation: Alejandra Pizarnik’s poems are full of a tense intimacy, like each word could say everything, so we gotta be careful with them. The hardest line to translate here was the first, specifically the phrasing of “sin para qué, sin para quién,” which translates as “without a reason, and for no one,” sense-wise. But I like the whimsy of “what/whom” and feel it’s in keeping with Pizarnik’s overall punk vibe.

[image error]

True story. I was working on a poem when I came across a draft that had the quoted text above in the middle of some rough writing. The quote stuck with me for a few hours, yet I couldn’t remember the source. So I decided to go the haibun-like route of including this story of the quote while letting the quote shine in its own space. I like the result, despite the poem showing how flawed my own memory is – and again, that could be the point, no, that words last?

[image error]

Those fragments on the side are from a hematite ring that broke a month ago. Found out recently that these rings break for two reasons, the brittleness of the metal, and when they have absorbed too much negativity. Words work in the same way, able to hold what they can, until they can’t.

[image error]

Talismans: The absence of my father growing up comes in and out of my poems. It’s an influence like weather, which changes. He died when I was six, but left my life earlier. In response to my worries about writing too many poems about this absence, someone called it a talisman of sorts, something I carry in the presence of these words.

[image error]

Throwback to the original version of a line that made its way into my book, Everything We Think We Hear (Floricanto Press). It got revised into: “Stay with me, love, the world is ours for the aching” which is recalled by the speaker of the newer poem as lines he used to say trying to be slick. True story.

[image error]

When you write poems in more than one language, you realize quickly how what you are really doing when you write is translating something yet spoken inside you into a shape and expression. Here, I like how the filter places a bit of light in the space between the two versions of the poem, light like a fingerprint itself.

[image error]

February brought my first attempts at erasures/blackout poems for the poetryamano project. My first attempts, like here, were done on my phone, using photo studio to mark out words. This one reads: “the real world / dwells in the / absorption of passion, / And / mirrors it” – From The English Renaissance of Art by Oscar Wilde.

[image error]

This last one of the month comes from a time when I’d walk around all poet-lonely, then go home and write poems about walking around being poet-lonely. We all went through that, right?

*

Happy amano-ing!

José

November 9, 2017

new audio!

Just a quick post to share this clip of me reading my poem “Flea Market” which will be featured in the next issue of The Inflectionist Review!

Thank you to John Sibley Williams and A. Molotkov for the opportunity to put these words on the air!

See you Friday!

José

November 3, 2017

poetry feature: Oka Bernard Osahon

This week’s poem is the first poetry feature drawn from submissions! For guidelines on how to submit work, see the “submissions” tab above.

*

Often when I read a love poem, I find myself most invested in what the poem evokes in terms of connection and disconnection. Love poems aren’t love, but are expressions of the world around a love relationship, a world made up of inside jokes, shared intimacies and understanding. The reader of a love poem is privy to something akin to gossip and confession, and involved in an engaged listening.

[image error]This week’s poem, “When We Are Too Tired to Fall in Love” by Oka Bernard Osahon, is a great example of a poem that makes the world around a relationship come alive for the reader. Line by line, the speaker of this poem engages the narrative of their relationship through imagery. Lines like “I felt the cold retraction / Beneath the glare of tossed hair as you carried the pages of your face away,” which moves from the visual “glare” to the tactile “pages” in its efforts to render a passing moment, run on an engine of imagery. Yet, the use of “pages” also implies change, and creates a sense of urgency.

The poem continues in lines that reach for similar turns of understanding. The use of imagery gives a sense of control in a poem that digs into the feeling of a relationship slipping out of one’s control, from connection to disconnection. Similar to “pages,” the use of the word “show” in the final line rings out beyond itself, reflecting on the relationship and the moment, as well as the fact of the poem itself.

*

When We Are Too Tired to Fall in Love – Oka Bernard Osahon

We laughed without moving our lips –

Our eyes – signs of joy fading – crowfeet wrinkled gaze.

We taped our selves together within the ineffective hug of weathered arms

And our thoughts shivered between us like a ghost trying to stay alive.

Our feet carried us away from our shadows – excuses and regrets limping behind

And when you stumbled into me on the steps, I felt the cold retraction

Beneath the glare of tossed hair as you carried the pages of your face away.

We lost a moment, when we could have found a tiny piece of what was lost.

We are unraveling even as I speak,

Like a single thread off the warp and weft of the table cloth

That hold the old china your mother gave you.

We are bartering words for points and we have lost so much in this match.

There was meaning in our trading once – with loud voices and broken fragile things

But now the words are bland and though we have not grown carapaces,

We are too worn out to fight the hurt. So we sit on the couch – two distant halves

Watching a show that used to make us laugh.

*

[image error]

Oka Benard Osahon is creative writer, poet and fantasy novel addict from Benin, Edo State, Nigeria. He attained his B.A in English and Literary Studies at Delta State University, Abraka. His poetry can be found on Brittle Paper, Kalahari Review, Praxis Magazine Online, Spillwords and Visual Verse. He was one of the winners of the Praxis Magazine Online 2016 Anthology Contest as well as the winner of the June 2017 Edition of the Brigitte Poirson Poetry Contest. He lives and works in Abuja where he writes at night after work. He can be reached at Twitter: @serveaze

October 27, 2017

artificing with denise levertov

[image error]What occurs in this mix of looking backward and forward is an evocation of the personal meaning of the wedding ring; this evocation isolates the ring, and allows for an imaginative distance. The “artificer” imagined towards the end who is able to re-work the ring strikes me as a metaphor for the poet. In poems, we work “simple gifts” out of the materials of a fleeting existence.

The Wedding Ring – Denise Levertov

My wedding-ring lies in a basket

as if at the bottom of a well.

Nothing will come to fish it back up

and onto my finger again.

It lies

among keys to abandoned houses,

nails waiting to be needed and hammered

into some wall,

telephone numbers with no names attached,

idle paperclips.

It can’t be given away

for fear of bringing ill-luck

It can’t be sold

for the marriage was good in its own

time, though that time is gone.

Could some artificer

beat into it bright stones, transform it

into a dazzling circlet no one could take

for solemn betrothal or to make promises

living will not let them keep? Change it

into a simple gift I could give in friendship?

October 20, 2017

inspired by richard wilbur

One wading a Fall meadow finds on all sides

The Queen Anne’s Lace lying like lilies

On water; it glides

So from the walker, it turns

Dry grass to a lake, as the slightest shade of you

Valleys my mind in fabulous blue Lucernes.

The beautiful changes as a forest is changed

By a chameleon’s tuning his skin to it;

As a mantis, arranged

On a green leaf, grows

Into it, makes the leaf leafier, and proves

Any greenness is deeper than anyone knows.

Your hands hold roses always in a way that says

They are not only yours; the beautiful changes

In such kind ways,

Wishing ever to sunder

Things and things’ selves for a second finding, to lose

For a moment all that it touches back to wonder.

[image error]

*

I remember first reading this poem by Richard Wilbur and just holding my breath: those last lines speaking sundering “things and things’ selves for a second finding,” speak to what I see as the crucial gift of lyric poetry. How, for example, even the word beautiful, a word poets in general are wary of, is reclaimed, refreshed in this poem, made a thing in motion. This is what Wilbur means.

Richard Wilbur’s recent passing has me thinking again on his work, on the poems that mattered to me as I read his books. A great formal sensibility and nuance. He, alongisde WH Auden, Donald Justice, and Rhina P. Espaillat, inspired me to go inside forms and find a pulse. Moving a person to go and write, that is one of the greatest compliments to a poet, and one of the greatest gifts the reading of poetry has to offer.

Below is my own poem inspired after my first reading of Wilbur’s poem years ago. I don’t know if I give anything back or refresh the word beautiful. This poem came in one of my seasonal sprees of bad sonnets. I do know that I wrote it at a time where the friendship invoked was one of the few things keeping me going. Which is another way friendship works, even at a distance. Engaging in the creative space of poetry writing brings one in communion with others who have taken the time to catch something of how the world “changes.”

*

The Beautiful Poems – José Angel Araguz

My friend set down to write the beautiful poems,

Set himself against lightning storms,

Against crowded rooms and bars where men belong

To each other and hold in an almost fist

Small shots of pain. In such a room, I lost him,

And he went on and became one among faces to remember.

The years have gone and I have yet to write

Much of anything myself; still, each night

I chase ghosts until the sky is an ember

And cracks, until I find myself thinking of him,

What he might be writing for the lovers who kissed

His eyes to visions. Tell me, is there no drink strong

Enough to unbolt proud hearts where only silence roams?

Tell me, are these the beautiful poems?

October 13, 2017

seeing with jennifer met

One of the great pleasures of writing reviews is catching onto things that poems do when they live together in a book. By “things” I mean, of course, the standard fare of themes, symbols, imagery, etc., but also something for which I am learning/discovering the technical terms for. In teaching, I often use the words engine or guiding principle, words that imply the mechanical and structural. Yet, what these words point to in my own use is more in tune with intuition.

[image error]In my recent microreview & interview of Jennifer Met’s compelling chapbook Gallery Withheld (Glass Poetry Press), I center my discussion around two visual poems whose layout on the page become another aspect to explored by reading. Through the visual poem form, one is able to guide text in the same way a spoken word or slam poet is able to command attention via vocal tone and gesture. Because of the presence of visual poems in Met’s collection, I couldn’t help but pay attention to the other poems that were more traditionally lineated. As a reader, these other poems became charged with importance, evoking a number of new questions: How is the vision of the collection different in these non-visual poems versus the visual poems? Where is the line drawn between what is on the surface a visual poem and what is, in my imperfect terms, a more traditionally lineated poem?

In answer to this last question, I present the poem “Collaboration” below whose presence on the page could be said to have a foot in both visual and lineated ideas of poetry. The poem is a complex ekphrastic that sneaks up on you; that is, the speaker goes from contemplating a photograph of the aftermath of an earthquake to the cover of an issue of The New Yorker. This move comes naturally, and what develops in the speaker’s meditation are images of a crack in the ground. These images are evoked, in part, by the visual layout of the lines of the poem. But beyond this, the meditation advances in such a deft manner, that what the reader is left with is not only an image but a way of imaging and imagining. This poem, for me, is at the conceptual heart of the collection because of the way it creates an engine out of seeing with which the reader is invited to see “the flowers float seemingly at random” at the end. These flowers are both an image and a motion. While there is so much seeing done in Gallery Withheld, it is done via poems which invite the reader to “collaborate” in the seeing, an interaction that is its own distinct poetic accomplishment.

Collaboration – Jennifer Met

for Christoph Niemann and Françoise Mouly

When I was young I saw a photograph

of a fence after an earthquake

where its man-made border was interrupted

as one half was heaved forward and

one half was pulled back leaving a large gap

like a warped spring—a latch

that can’t quite be forced close or like someone

painting a line down the right

side of a large and invisible street fell

asleep and when they woke up

they accidentally resumed their drawing

on the left side instead—the width

of a street—a common ground—a public right

of way owned and maintained

by the city—now left unconnected and you

couldn’t see where the earth ground

against itself sliding or where it rippled

like a blanket being shaken

because there wasn’t a mark and wasn’t a rift–

wasn’t a scar in the grass—and I

always associated this image with earthquakes so much

so that now the New Yorker’s cover

illustration reminds me of an earthquake fissure

the leafless cherry branch like lightning

slightly off-centre and striking upon the left-hand

side of the page where trefoils blossom pink

and loose petals drift back and up and I think

how the artist’s editor was right

to change the background color of this dark

crack canyoning up the beautifully clean

white—too obvious—to a new version of a branch

drawn black against black—unseen–

and the flowers float seemingly at random…

*

Happy seeing!

José

October 9, 2017

microreview & interview: Jennifer Met’s Gallery Withheld

review by José Angel Araguz

[image error]

[image error]

At the end of “Coming of Age in Idaho,” the second poem in Jennifer Met’s chapbook Gallery Withheld (Glass Poetry Press, 2017), the reader is presented with the phrase “an immovable feast” which hearkens back to Ernest Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast. This reference is key on a number of levels beyond wordplay. For one, much of the poems in Met’s book challenge and subvert the very stereotypes and gendered double standards that make possible the aura of a writer like Hemingway. Rather than rail against said aura directly, these poems imply it through sharp insights. As Idaho is “Hemingway country” and the site of his final days, the speaker’s “coming of age” is akin to rising from the ashes of a certain kind of writing tradition and taking flight into another.

Which is where another level of meaning can be found: this collection brings together lyric poems that trouble traditional poetics through engaging, experimenting, and expanding upon the visual poetry and projective verse traditions. Each poem can be seen as “an immovable feast,” either fixed on the page through intuitive choice or fixed into shape through a formal choice. In “The Object of His Desire,” for example, the narrative of a young boy collecting rocks is troubled when presented in the poetic shape of a woman. This confluence of content and form is purposeful and distinct; if the words were flushed left, they’d still be the same words, but they wouldn’t say the same thing they say in this shape. It is the gift of a visual poem to engage with a language’s plasticity and provide opportunities for multivalent, complex readings. For example, as the poem ends on the idea of facelessness, one can’t help but return to the shape of the poem, and note that where a woman’s face would be are the words: “You see / I’ve always / been drawn / to metaphor.” This implies another facelessness, a societal one. The casual tone of these words further point to the learned narratives of childhood and their insidiousness.

This critique of stereotypes continues in “Old Made: Self-Portrait in a Negative Space,” (below) which lives across from “The Object of His Desire” on the facing page. Where the shape of a woman is the shape of the poem in “Object,” in “Old Made” a woman’s shape is everywhere the poem is not. Even in describing this difference due to formal choice carries with it some of the charged critique that is everywhere in the poem. The assumptions behind the phrase “old maid” are challenged in the title; the rephrasing to “old made” implies how ideas of “old” are “made” in lack of knowledge and lack of connection. It is telling, then, to consider the way this poem ends and begins with the word “Us.” Stereotypes like the one challenged here can make a person feel that they are nothing in the face of others. This feeling is further implied in the form; where the woman’s face would be in this shape, there is instead a list of conjunctions, “if….and….but.” Which is to say that where a face, one’s most personal, recognizable feature, would be, there is instead a brief scatter of words standing alone. Read alone as they are, this list could be read as a half-started, unfinished, and unlistened to protest.

The poems of Gallery Withheld again and again make space to listen and engage with the half-started and unfinished. Reading these poems, one is left like the speaker in “Lefty Loosey” who contemplates Robert S. Neuman’s painting “Monument to No One In Particular” along with another woman who

contemplates

the structure with a frown

and when she leaves I take

her angle hoping

for direction

Each of these immoveable feasts invites the reader to come closer to the text in their reading. And like the speaker above, we must reflect that “its chaos is just / not meant for me or her / or my father in particular / but us all.”

[image error]

Influence Question: How would you say this collection reflects your idea of what poetry is/can be?

Jennifer Met: I don’t have an MFA and my undergrad degree is in Molecular Biology, so I have a very open opinion of what poetry can be—I am not limited by an idea of what a perfect “workshop” poem should sound like in order to be accepted as real, good poetry. In fact, I am often drawn to forms (like haiku/haibun, speculative, ekphrastic, and concrete poetry) that seem to have more of an outmoded or niche status in the contemporary poetry scene. In a time when poetry has such a limited readership I think it is silly of us to narrow the definition of what poetry can be. I love to read and write widely, and without labels!

In this vein, Gallery Withheld contains poems that have abandoned frames and formal spaces of presentation. They run the gamut from experimental to lyrical to narrative and contain variations of haibun, ekphrastic poems, persona poems, and more. While they share thematic elements exploring definitions of gender, objectification, and the intersection of word, art, and identity, the main binding thread of the collection is that the form of each poem contains some sort of shape/concrete element. More than just a gimmick or a literal, visual shorthand of the content, I think a good shape, like a good title, can lend an extra layer of meaning and engagement to a written piece. It is particularly important in these identity poems as we are so often judged and defined by our visual elements.

For example, take the poem “Object of His Desire” from the collection (originally appearing in experimental poetry journal The Bombay Gin). On the surface it is a charming anecdote about a child keeping pet rocks in an egg carton, but add the shape—an icon—a perfect, bathroom-door skirted woman—and the words become much more sinister. You notice how the rocks are being objectified and their plight becomes symbolic. Sure, they are treated nicely, but are “animals” (implying a hierarchy), and taken care of (again, implying power), named (implying possession and external definition/validity). Then, when the rocks, just like the woman-icon shape, are left without faces, we see how their feelings, even their individuality, ceases to matter. How without eyes, nose and mouth, they are unable to sense stimuli. Static—unable to interact with their environment, process or ever change. Trapped unable to speak and respond. But without any sensory input, they are unaware that this is even an issue—the system feels perpetual, grand, safe, even desirable. Hence the poem becomes the definition of “woman” as seen not just by a man, but by us all—a blank, yet somehow identifiable, object. However, this meaning only exists when the text is paired with the shape.

Influence Question: What were the challenges in writing these poems and how did you work through them?

Jennifer Met: One of the challenges in writing these poems was wrestling with their literally “concrete” nature. Generally I started with an anecdote (narrative or image-based), then formed the polished prose into a meaningful form while trying to be mindful of good line breaks. However, poetry is such a fluid and organic process that this proved limited—the content would inform the shape, which would then re-inform the content, which would then re-inform the shape, in an endless cycle. However, it is not easy to cut or change even a single word without seriously disturbing a set, concrete, typographic shape, so I found myself constantly constructing a shape only to take the writing back out and revise it before reworking it back into a form. Because of this I actually felt the freedom to do a lot more straight-out rewriting than my revisions would usually entail.

Rewriting seems like a lot of work, and even a betrayal of our charged first-words, but it benefitted this collection so much that I have continued the practice in my current poems to great success. While changing single words or just reworking stanza breaks has never been my idea of revision, I have started to really scrap and rebuild poems—often saving only a few phrases, a single image, or even an idea that had unexpectedly developed during its initial writing—a process I highly recommend.

*

Special thanks to Jennifer Met for participating! To find out more about her work, check out her site. Gallery Withheld can be purchased from Glass Poetry Press.

[image error]Jennifer Met lives in a small town in North Idaho with her husband and children. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee, a finalist for Nimrod’s Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry, and winner of the Jovanovich Award. Recent work is published or forthcoming in Gravel, Gulf Stream, Harpur Palate, Juked, Kestrel, Moon City Review, Nimrod, Sleet Magazine, Tinderbox, and Zone 3, among other journals. She is the author of the chapbook Gallery Withheld(Glass Poetry Press, 2017).

October 6, 2017

blues, song, & sea: amiri baraka

The distance between the list poem and the ode varies. A list poem, for one, implies attention, if not praise. Yet, the act of listing is the act of making space and placing importance on a subject. Odes, which are made up of mainly attention and praise, also create an empathic space for readers. Whenever I begin to see a list occurring in a poem, I take it as a cue to listen/watch closely: something is being paid attention to in an engaged manner.

In this week’s poem, “Legacy” by Amiri Baraka, what is listed is a series of actions: sleeping, growling, stumbling, frowning, etc. There is a momentum generated in this listing of actions that embodies the tortured tone of the speaker. I call it a “tortured tone” but not a passive one; what this list of actions brings attention to is the act of evocation made possible by song. This speaker goes on to tell us that “(the old songs / lead you to believe)” in the sea. To expand on this logic: Songs, which exist on the air, can create hope, illusion, feelings, etc. out of the very air that holds them.

In this week’s poem, “Legacy” by Amiri Baraka, what is listed is a series of actions: sleeping, growling, stumbling, frowning, etc. There is a momentum generated in this listing of actions that embodies the tortured tone of the speaker. I call it a “tortured tone” but not a passive one; what this list of actions brings attention to is the act of evocation made possible by song. This speaker goes on to tell us that “(the old songs / lead you to believe)” in the sea. To expand on this logic: Songs, which exist on the air, can create hope, illusion, feelings, etc. out of the very air that holds them.

This poem is dedicated to “Blues People,” and what these people mean to the speaker can be felt through this listing and attention to action. This list itself becomes like the sea, existing in motion as long as the poem is read.

Legacy – Amiri Baraka

(For Blues People)

In the south, sleeping against

the drugstore, growling under

the trucks and stoves, stumbling

through and over the cluttered eyes

of early mysterious night. Frowning

drunk waving moving a hand or lash.

Dancing kneeling reaching out, letting

a hand rest in shadows. Squatting

to drink or pee. Stretching to climb

pulling themselves onto horses near

where there was sea (the old songs

lead you to believe). Riding out

from this town, to another, where

it is also black. Down a road

where people are asleep. Towards

the moon or the shadows of houses.

Towards the songs’ pretended sea.

from Black Magic (Bobbs-Merrill, 1969)

October 5, 2017

latest review for The Bind!

Just a quick post to share my latest creative review for The Bind!

Just a quick post to share my latest creative review for The Bind!

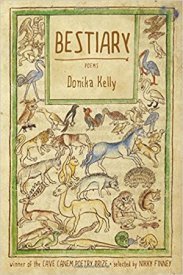

This time around I review Donika Kelly’s powerful collection Bestiary (Graywolf Press) and create a writing prompt based on Kelly’s work!

Check out the review and prompt here.

José