Matthew Buscemi's Blog, page 25

August 10, 2017

Achievement Unlocked: Insomnium, Second Edition

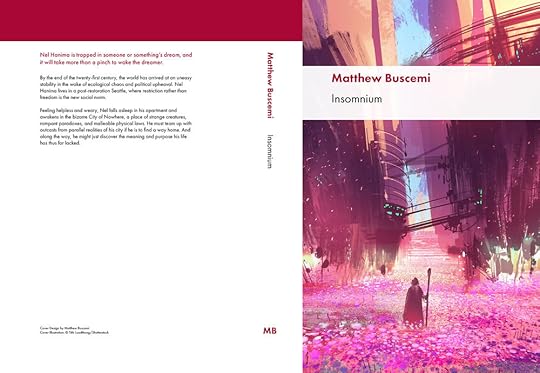

Insomnium is a weird novel.

It possesses both surface and sub-surface weird. A group of people, each from parallel realities of late-twenty-first-century Seattle, wake up to discover themselves in the City of Nowhere, a place populated with anthropomorphoid creatures and sectioned off into "wards," each of which operates according to different physical laws than the others.

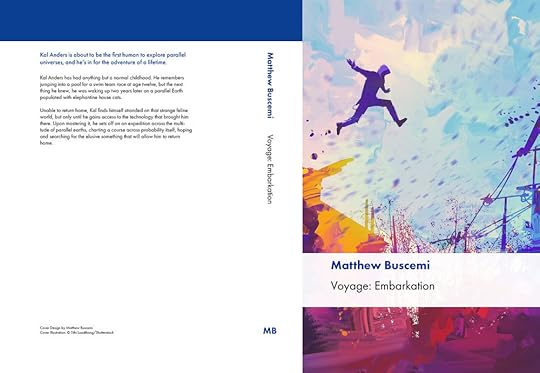

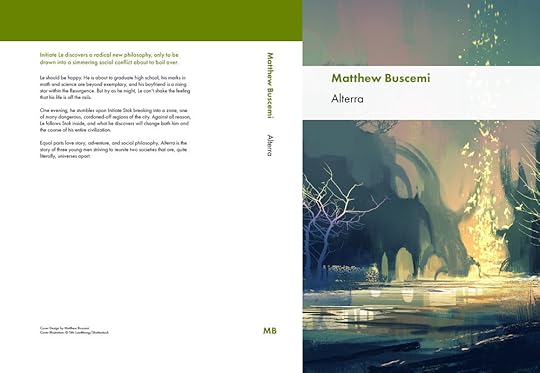

Two weeks ago, when I released the second edition of Alterra, I wrote about how that novel was a turning point in my writing. Insomnium marks an earlier victory, smaller but still important. Within science fiction, there exists a certain ideological group of writers and readers who believe that technology is the absolute measure of human progress and that the goal of science fiction literature is to proselytize the scientific worldview and aggrandize scientific achievements. While writing Voyage: Embarkation, I endured and attempted to incorporate significant amounts of such feedback, but it took only a few months for me to realize how misguided such feedback was.

The big shift with Alterra was still a year off, but when I sat down to write Insomnium, I reflexively reached for the bizarre, for an opportunity to twist, contort, invert, and skew the physical laws of the universe each and every way I could. In response to my detractor's insistence that I be more "scientific" I served up a story whose setting was inspired by Escher.

Insomnium also wasn't supposed to happen.

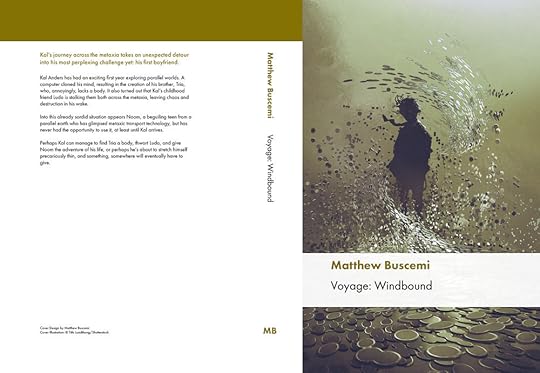

There was a confluence of situations at the beginning of 2013. I was putting Voyage: Embarkation through its final editing paces, and I was simultaneously writing the first draft of Voyage: Windbound, the second book in the Voyage series (which proceeds to Adrift, Wake, and finally Tempest). In February 2013, for reasons I'll go into in another blog post, I found I could no longer work on Windbound.

I set that manuscript aside and began Insomnium instead. I remember being conscious of the fact that I wanted to use the setting to poke fun at the science absolutists. What I was not consciously aware of, at least until I was a good way through the manuscript, that Insomnium was the novel that I needed to write in order to be capable of finishing Windbound, which I did. The moment Insomnium's first draft was done, I returned to Windbound and found myself able to continue through it.

Sometimes the novel a writer wants is not the novel a writer gets. Sometimes what a writer wants to write, and what a writer needs to write are two different things entirely. This is one area where I feel I have a big advantage over people trying to make this their living at novel writing. If I need to scrap a project and start another, I can. I wrote in the introduction to Lore & Logos about how restrictions can drive creative development. Freedom more certainly can, as well. The trick is getting them in the right ways and at the right times.

Insomnium explores people who have made mistakes, really big ones, and all emotions that come with that. It explores sorrow, it explores loss, it explores persecution, and it explores something like redemption. More like owning up to where you've been and how you got yourself there so that you can build a better present. It makes some not-so-subtle allusions to this happening at the societal level, too.

Insomnium is a good novel for the times we live in now, for the answer is not more hatred, more blame, more regret, more angst, more recrimination, nor more selfishness. The answer, at least to such problems as the one described above, is forgiveness.

Insomnium By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview

Insomnium By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview  Paperback ($16.99)

Paperback ($16.99) Insomnium By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview

Insomnium By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview  Hardcover ($29.99)

Hardcover ($29.99)Goals Progress

Voyage: Embarkation

Release a second edition with a new introduction, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

Insomnium

Release a second edition in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

Alterra

Release a second edition paperback and hardcover.

Update the ebook formatting.

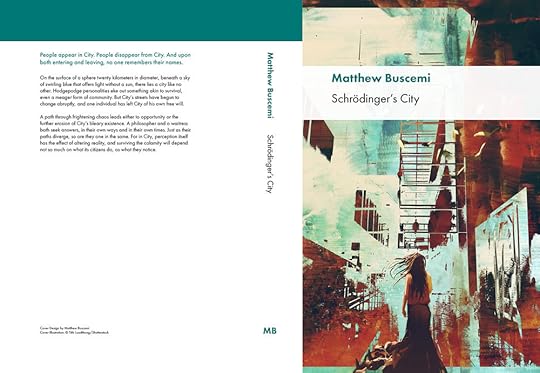

Schrödinger's City

Release a second edition paperback and hardcover.

Update the ebook formatting.

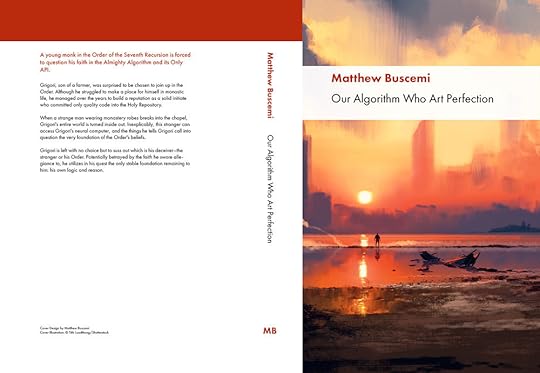

Our Algorithm Who Art Perfection

Release a first edition paperback and hardcover.

Update the ebook formatting.

Voyage: Windbound

Release the first edition, including an introduction about why it took me three years to release this novel, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

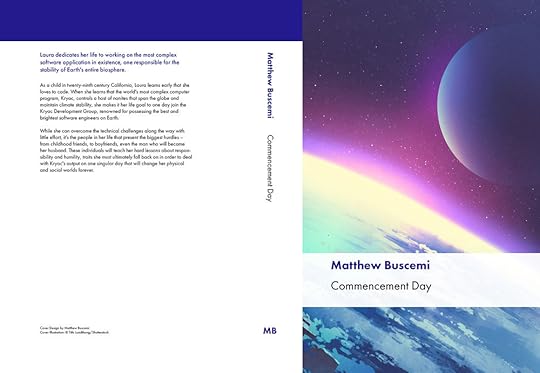

Commencement Day

Release the first edition in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

July 28, 2017

Achievement Unlocked: Alterra, Second Edition

At the end of 2013, I was searching for something new to write about. It had been a tumultuous but productive year for my writing. I'd begun Voyage: Windbound, gotten fed up with it halfway through, written a completely new novel instead (Insomnium), then gone back to Voyage: Windbound and finished it (without publishing it).

And so I found myself, in the final months of 2013, searching for the next story I would tell.

In the middle of Insomnium, I'd written a short story one weekend on a whim. In the middle of all the angst of Insomnium and Windbound, it felt good to write something very simple, a brief interlude about two guys in love.

This was fine for a short story. I had never intended it to be anything more than a flight of fancy. However, after Windbound, I found my imagination straying toward that short story whenever I thought about my next novel, and at first I actively resisted that impulse. A Matthew Buscemi novel can never be merely a romance; it has to explore ideas. When I realized what the romance meant to the two guys involved, and most especially, a third guy was not involved, it was then that I realized what Alterra was really about, and with it, I was able to put a capstone on one era of my writing, and usher in an entirely new one.

The more my writing develops, the more I realize that Voyage: Embarkation, Voyage: Windbound, Insomnium, and Alterra are different from all the writing that came after them. They represent a phase of my development that I find myself still proud of, despite the fact that I will never write quite that way again.

Alterra is three things. It is a love story, it is an adventure, and it is also philosophy. The love story is the foundation for the other two. An ideological divide separates two boyfriends, Le and Shey, then unites Le and Stok, but the latter relationship, like the society these men live in, is unstable. In order to find one another again, they will have to combat the broken belief systems imposed by the culture they live in at the story's start, and the culture Stok discovers as the adventure portion of the story kicks in.

The protagonists of the book are able to stand up to cultural rigidity and intransigence and insist on a better future. I didn't realize it at the time, but I actively carried out such a philosophy in my personal life during Alterra's production. The main reason that it represents such a shift in writing, is that with Alterra, I was finally able to recognize the malign feedback I was subjecting myself to as malign. It was with this novel that I demarcated lines of quality I would not compromise and formulated stylistic principles that I would not breach for the sake of potential popularity or profit.

Alterra's observations about technology and religion are more relevant than ever, especially after what has happened politically since this novel's first printing three years ago. We can no longer afford simplistic thinking or self-satisfied disaffection. Our world is changing, and so must we.

I have re-released Alterra first, because the revisions have been ready to go for over a year. When I still had Fuzzy Hedgehog Press, Alterra was my first novel to sell out. I prepared a second edition, but by the time I was ready to print it, I found my financial resources for the press dwindling, and I was unable to justify the print run.

In this edition, I have affected some minor edits, mostly stylistic changes, but a few substantial ones as well. I found a scene involving Le and Stok being clever with technology that needed readjusting, and I had wanted to improve Le's conversation with the Deranged (one of my personal favorite scenes) since shortly after the printing the first edition. Those changes are here, but it remains largely the same novel as the first edition.

I offer the text of Alterra now with a new cover and new interior design, which I will be using for all my books going forward. You can download the updated PDF free from this website, and you can also purchase a paperback or hardcover from my portal on Blurb.

Alterra By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview

Alterra By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview

Paperback ($11.99)

Alterra By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview

Alterra By Matthew Buscemi Book Preview  Hardcover ($24.99)

Hardcover ($24.99)Goals Progress

Voyage: Embarkation

Release a second edition with a new introduction, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

Insomnium

Release a second edition in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

Alterra

Release a second edition paperback and hardcover.

Update the ebook formatting.

Schrödinger's City

Release a second edition paperback and hardcover.

Update the ebook formatting.

Our Algorithm Who Art Perfection

Release a first edition paperback and hardcover.

Update the ebook formatting.

Voyage: Windbound

Release the first edition, including an introduction about why it took me three years to release this novel, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

Commencement Day

Release the first edition in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.

July 25, 2017

Goals

When I closed down Fuzzy Hedgehog Press last year, I ceased all publishing operations, including printing my own books. I knew that I wanted to continue getting my books into the world in some form, but I had to clean up my mess first.

Now, seven months later, I find myself in a much better position. My business and all its associated administrative functions have been shut down, and my apartment is now my apartment again. Remaining copies of previous editions of my books have been moved to storage.

A few months ago, I started looking into book printing again, this time determined that I would not end up paying enormous sums for print runs. I wanted to a place that would set up my books for print-on-demand direct to customers for a reasonable price, at a quality that is not egregiously low, and with distribution terms that respected my intellectual property.

I have now found such a printer.

I can now make beautiful print versions of my books available to anyone at low cost, while continuing to provide free ebooks from my website. The ones currently available, by the way, need an upgrade. When I prepared the extant copies of Alterra, Schrödinger's City, and Our Algorithm six months to a year ago, I simply output the print book into ebook form, but I realize now that the ebooks need their own formatting.

In the next five months and change, I plan to accomplish the following:

Voyage: EmbarkationRelease a second edition with a new introduction, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.InsomniumRelease a second edition in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.AlterraRelease a second edition paperback and hardcover.Update the ebook formatting.Schrödinger's CityRelease a second edition paperback and hardcover.Update the ebook formatting.Our Algorithm Who Art PerfectionRelease a first edition paperback and hardcover.Update the ebook formatting.Voyage: WindboundRelease the first edition, including an introduction about why it took me three years to release this novel, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.Commencement DayRelease the first edition in ebook, paperback, and hardcover.This may look like a lot of work, but, in fact, it should fit inside six months. Insomnium, Alterra, Schrödinger's City, and Our Algorithm are "ready to go" from an editing/proofreading standpoint and simply need to be laid out in the new format. The Voyage books need a little more editing, but not much. That leaves only Commencement Day, the draft for which is currently at around 60-70% completion.

And I have covers.

Look for these to come available over the next five months. Subscribe to this blog to find out when each title and format becomes available.

July 12, 2017

Schrödinger's City Illustrations

The very talented Zhivko Zhelev has just put the finishing touches on a batch of illustrations I commissioned from him for a limited edition copy of Schrödinger's City that I'm going to have printed. You can find all of the illustrations over on the Schrödinger's City web page of this site, and you can see Zhelev's other work on his DeviantArt page.

June 24, 2017

Lessons From Publishing, Part 2: Typesetting

Three and a half years ago, I set out on the adventure of becoming a publisher. Although I have shut down the economic entity representing my publishing endeavors, known as Fuzzy Hedgehog Press, the parts of publishing most interesting and valuable for me remain. As I discovered, those valuable bits have nothing to do with the operation of a business unit.

If, like me, you are a writer and publisher more interested in crafting literary art than in turning a monetary profit or becoming popular, then this series is for you.

TypesettingOf all the skills I picked up on my publishing journey, my favorite, far and away, is the art of typesetting. It consists of the ability to lay out a page that is both readable and elegant, a skill that, for all its surface simplicity, contains remarkable depth.

When I started out three and a half years ago, I merely surveyed all the fiction I owned and mimicked the elements of the layouts I liked best. Once I had a half dozen designs under my belt, I came to realize that what I thought was a simple affair—text block here, page numbers there—was actually a highly complex medium, and not to mention, one highly sensitive to minute changes.

In this article, I will summarize what I have learned about typesetting a book for print. I have four major sources: The Form of the Book by Jan Tschichold, The Elements of Typographic Style by Robert Bringhurst, On Book Design by Richard Hendel, and Book Typography: A Designer's Manual by Michael Mitchell.

SoftwareAt the time of this writing, there are two professional software applications used to lay out book interiors, Adobe InDesign and QuarkXpress. I personally use Adobe InDesign.

These applications are admittedly pricey. Unfortunately, no good free and open source option exists. The closest is Scribus, but this application's main failing, when I last investigated it six months prior to the time of this writing, was that it refused to read in any fonts that did not conform to its bizarrely dogmatic standard of "correctness." Unfortunately, this excluded many legitimate and beautiful fonts. I can recommend Scribus as a sandbox in which to practice typesetting without incurring the fees of the professional products, but that is all.

All of the above software is designed to output layouts as PDF files. The PDF format is the standard amongst all book printers I have ever worked with. Even custom dies for book binderies are cast from PDFs these days.

TerminologyI'll need to start by establishing some basic terminology, as Mitchell was kind enough to do in Book Typography.

When you open up a book, typically you are looking at two pages. These two pages together are called a spread. The left page is called a verso and the right page a recto. Printers expect to get book layout files in an even number of pages, beginning with a single recto page, ending with a single verso page, and containing some number of spreads in between.

Most pages will have page numbers, which amongst typesetters are called folios. Odd numbered folios must appear on rectos, and even numbered folios on versos.

The part of the page where the text appears is called the text block, and the empty parts of the page around its edges are called the margins. There are four margins: the inner margin, the outer margin, the top margin, and the bottom margin. The top margin and the bottom margin are in the places their names suggest them to be: the top and bottom of the page respectively. The inner margin sits against the spine, so the inner margin lies on the right of a verso, and on the left of a recto. The outer margin lies against the outside page edge, which is on the left of a verso, and on the right of a recto.

The text may or may not have running heads, a running head is a line of text, which can consist of the author's name, the title of the book, or the title of the current section or chapter, which sits atop the text block. Some publishing houses insist that they be included, but some professional typographers find them to be unsightly in a work without chapter or section titles.

Most print works of fiction will have the following parts, though some are optional: the half-title, the title page, the copyright page, the dedication, the table of contents, the introduction, and the text. The order of this list is, generally speaking, the order in which these sections should appear.

A print work of fiction will have three major sections, the front matter, the text, and the back matter. The pages of the front matter are numbered with lowercase Roman numeral folios, and the pages of the text and the back matter are numbered with Arabic numeral folios. The first page of the front matter should be page i and the first page of the text should be page 1. Since odd numbers need to be on rectos, it is common to add a blank page to the front matter if it has an odd number of pages. Otherwise, page 1 of the text would be on the wrong side of the spine.

The Text Block and the Van de Graaf CanonOne of the most important decisions the typesetter will make is that of the size and positioning of the text block upon the page. It determines the shape of absolutely every page in the book, even those without blocks of continuous text.

When I was preparing to typeset the first edition of Voyage: Embarkation (my first novel), I surveyed the typesetting of my favorite books. A couple of things jumped out at me, especially as I considered the effects of the text block on how I read:

I liked it better when the text box was far enough away from the spine so that I didn't have to tilt the book into the roll of the spine to see the words properly.I liked it better when there was enough room in the outer and bottom margins for my thumbs when I was holding the book open. If either of those margins was too narrow, my thumbs would cover up the lines, and I had to shift my hand positioning constantly as I read.As a result, I ended up with this design for the text interior:

[image error]

Example spread from "Voyage: Embarkation" first edition hardcover

Text excerpts Copyright © Matthew Buscemi 2013

I made the inner margin huge, to keep the text away from the spine, and the outer and bottom spine was large enough to accommodate fingers. I set the top margin to something that looked right, given the proportions of everything else (I should note that in the above example, my earliest work, I put the running heads inside the text block space, which I now feel was a mistake). I put folios and the standard running head at the top and called it a day.

To my eyes now, I consider this a good first effort, but it is crude. Once I started reading up on typesetting, I discovered other considerations.

One of the goals of a good text block design should be to make the text legible within a spread, not a page. When the text block is pulled out from the spine, as I did with my first edition of Voyage: Embarkation (and five more books afterward), I broke that unity.

I was right in my thinking that the text should not roll inward toward the spine, but by leaving the outer margin smaller than the inner margin, I made the text appear to be two blocks on two disconnected pages, when, in fact, these pages should feel connected.

In The Art of the Book, Jan Tschichold discusses a property he discovered of medieval books. He noticed that a great many of them had the same text block proportions, even though page sizes varied wildly (there were not yet standards among paper makers).

The trick, he discovered, was a mathematically derived arrangement for the text block, one which medieval printers could create with just a pencil and a straight edge, and results in text blocks with elegant properties. The most notable properties are that the height of the text block is the same as the width of the page, and that the text block height and width ratio always come out at the same as the page height and width ratio. Tschichold named this style of deriving the text block after the typographer who figured out how to draw the straight-edge lines that would yield such a text block regardless of paper size, Johannes A. van de Graaf (The Form of the Book, pg. 45; further reading)

On a page size of 6" by 9", the canon will yield the following: a ⅔" inner margin, a 1" top margin, a 1 ⅓" outer margin, and a 2" bottom margin.

[image error]

Example of margins delineating the Golden Section on a 6" x 9" page spread

This spread is elegant, but not economical. It leaves an enormous amount of whitespace on the page, and it does not leave enough margin near the spine for a book with a glue binding (which is all paperbacks, and some hardcovers, certainly every book created with print-on-demand services; only hardcovers with a sewn binding will find this inner margin acceptable). I have used the canon to print a one-of-a-kind edition, but it is simply not practical for most contexts.

As a result, my standard text block/margin rules for myself are now:

The inner margin must be as close to the spine as possible without rolling into it.The margins must increase in size in this order: inner margin, top margin, outer margin, bottom margin.The outer margin and bottom margin must be large enough that I can look at a spread and feel that the text blocks of each page are unified.Here's an interior text spread from the upcoming second edition of Voyage: Embarkation, which utilizes these principles:

[image error]

Example spread from "Voyage: Embarkation" second edition hardcover

Text excerpts Copyright © Matthew Buscemi 2017

The Half-Title

When the reader opens up the front cover of the book, they will be presented first with the endpaper. This is sturdy piece of paper glued to the back of each cover. Its practical purpose is to cover up whatever material the cover is made of. It is highly irregular for any text to be printed on the endpaper, but a design is common. In some fantasy books, such as my hardcovers of Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea series, a map of the novel's world is printed on the endpaper.

When the reader flips over the endpaper, they should be presented with the half-title. This will be page i, but it would be highly unusual for the half-title (or any other front matter page) to present a folio.

The half-title should be a very simplified form of the title page. Where the title page will list the author, information about the publisher, and even, if applicable, the sub-title, the half-title should contain the title in its most basic form. Voyage: Embarkation is a good exemplar of this difference.

Voyage Embarkation first edition half-title and title pages

Notice that the half-title contains only the most basic form of the title, "Voyage Embarkation," while the title page displays the entire extended title, "Voyage Along the Catastrophe of Notions / Volume I / Embarkation." Since I was a publisher at that time, I included the press logo and name as well. Some publishers put which cities they are based in, but I decided not to do that here.

This is a flawed design. I don't like the small caps everywhere, the five different font sizes, and the fact that some elements are centered and others are right aligned. I also hadn't yet learned about vertical unity among front matter pages when I made this design. The half-title should not be vertically centered on the page!

Below are the half title and title for the upcoming second edition of Voyage: Embarkation.

Voyage Embarkation second edition half-title and title pages

So, things have gotten a lot simpler, and in my humble opinion, typesetting is a craft where simpler is almost always better. There are exactly two font sizes at work now, and no small caps. Notice also the horizontal guide I've placed on these pages. This guide is set at the same position on all three pages. Front matter looks more unified (and more pleasing) when all elements are aligned to a guide (its placement can vary between books, but not within the same book).

This is one of the squishier rules. Start by aligning all front matter elements vertically, but if you find a really good reason not to, try it out and see how it goes. Starting out by having vertical alignment unity among your front matter pages is certainly preferable to placing elements willy nilly.

Finally, notice that in all the examples given, the elements of the half-title and the title are contained within the text block shape that we chose for the text, and they are also aligned (centering, right alignment, left alignment, everything) against the text block, not the page. This is extremely important. Whereas the vertical alignment rule is kind of squishy, the text block rule is decidedly firm. It would be highly unusual for a page of the front matter that breaks text block unity to look good. Some artistic elements, such as styles and graphics, may certainly bleed out, but it would be highly unusual for text elements to do so.

The Title PageThe title page should be on page iii, as shown in the above examples.

It is typical for page ii to be blank. Some publishers and authors like to put a list of the author's other publications or promotional material on this page. I did this for many of my earlier books, but nowadays I prefer to leave page ii blank. I find that ads or even the list of publications distracts from the title page, and then the title page has to be more embellished, and the more typesetting I do, the more I try to find the simplest solution that could possibly work.

The Copyright PageThe United States Copyright Office will recognize a copyright notice placed in any of the following locations within a book: on the title page, immediately after the title page, just inside either the front or back cover, or the first or last page of the main body of the text (source).

It is typical to place the copyright information, along with other publication information, on page iv. However, many typesetters have written that, although they find page iv placement of the copyright information unseemly, the publishing houses remain adamantly opposed to any other position. The typesetter's goal is to serve the reader, and thus the copyright information, which the reader does not typically care about, should, some argue, be placed at the end.

In all of my published books so far, I have placed the copyright page on page iv. Going forward, I will be placing copyright information on the very last page of the book, the very last section of the back matter, which is also compliant with the United States Copyright Office guidelines.

If you survey enough books, you will realize that there is no "standard" way to lay out a copyright page, except that the text is typically very small. Use your best judgment, keeping the text inside the text block and obeying the vertical alignment guide you set for the front matter (if your copyright page is in the front matter).

Schrödinger's City first edition copyright and dedication spread

Though it predates my knowledge of van de Graaf and vertical alignment, this copyright page from my first edition paperback of Schrödinger's City is a good example of the contents of a page iv copyright notification.

Above is the final page copyright notification from the second edition of Voyage: Embarkation. In this edition, page iv has been left blank. Notes about typography have been moved to their own special back matter section, and printing and press information, as well as legal notifications, have been omitted.

The DedicationThis page is usually simple enough. If there is a dedication, it should be on page v. Dedications are usually short. The font should be consistent with the font for the body of the text, and the same size, too. It is common to use italics. A lot of what looks good in a dedication depends on how long the dedication is. You will have to experiment and discover such nuances for yourself.

Be sure to follow your vertical alignment guide for front matter and keep everything inside of and aligned against the text block!

This is our first optional element. If there is no dedication, that's fine. Page v should then contain the next applicable element.

The Table of ContentsA table of contents should appear if a book has chapter titles, or if it is sectioned in some way other than plainly numbered chapters. The goal is to help readers quickly return to parts of the text they are trying to find. In a book with chapters that are merely numbered, a table of contents serves no purpose (no one is likely to remember that their favorite scene was in chapter sixteen, just that it was the part where the antagonist was finally defeated).

There are many different ways to style a table of contents. Again, I recommend doing a survey of books you own and seeing what others have done.

My personal preference is for chapter titles flush left with folios flush right against the text block.

Voyage Embarkation second edition table of contents

However, things get more complicated if there are multiple levels of sections and chapters.

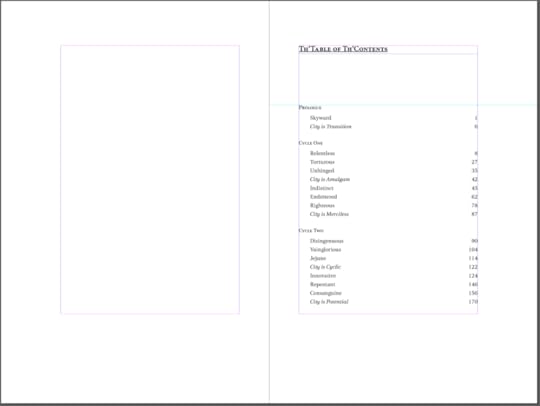

Schrödinger's City unpublished limited edition hardcover table of contents

Notice that lines need a lot of space between them in order for the reader to easily trace a line from the chapter title to the folio (space between lines of text is called leading). The less leading there is, the harder this tracing becomes.

If there is no dedication, the table of contents should appear on page v, otherwise it should appear on page vii. Some typesetters like to start a multi-page table of contents on a verso, so that the reader can see the entire table of contents on a single spread. I have mixed feelings about this. I like the idea of looking at the entire table of contents on one spread, but it is typical for every other major piece of front matter to start on a recto. If the table of contents starts on a verso, it can feel as though it has started "wrong." All I can suggest is that you do what you think is best.

The IntroductionWith the introduction, it is important to ask yourself whether the introduction belongs with the front matter or with the text. This has broad implications.

If the introduction merely provides additional context about the novel, then it should be part of the front matter. Its pages should use the lowercase roman numeral folios, and it should start on the first available recto.

If the introduction is a part of the novel, that is, if its contents is more like a prologue, then it should start on page 1. Again, make absolutely sure that page 1 is a recto. Odd numbered folios must appear on rectos.

The TextYou may be thinking that there's not much left to talk about with the text, since we decided the shape of the text block way back at the beginning, but the layout of the main text leaves a lot for us to discuss.

Chapter HeadersThe page that begins a chapter can either be a verso or a recto. Some typesetters like to start all chapters on rectos, but this will incur the cost of a blank page when the previous chapter ends on recto. This can significantly increase page count, and I have yet to discover a printer whose pricing structure does not increase per page.

Usually there is significant whitespace around the chapter title, and the text begins some ways down the page. Folios and running heads almost never appear on chapter header pages.

I have studied a lot of chapter titles in the books on my shelves, and that is about where the similarities end. This is another area where typesetters tend to get more creative (as should be obvious by now, my tendency is toward simpler designs).

[image error]

Example chapter header from "Voyage: Embarkation" second edition hardcover

Text excerpts Copyright © Matthew Buscemi 2017

Folios and Running Heads

The main pages of a text should include folios. I have seen these placed above the text block flush with the outer edge, below the text block centered, or below the text box flush with its outer edge. My personal preference is for the lattermost, but I have used other styles on occasion. In a book with very large margins (such as a design that utilizes the canon) it is possible to get even more creative.

Many typesetters I've read have complained about running heads. These typically appear above the text block, either centered or flush against the outside. They are extremely useful when the book has named chapters or sections, but useless for a continuous text. However, the house rules of some publishers dictate that all books must include running heads of the author's name and book title. I followed this convention for all my early publications, because I was mimicking what I saw in other novels. I now leave off the running heads in works where they are unnecessary. A running head of the chapter title (see above) can be very helpful to the reader who is searching out a particular section of the text.

Running heads and folios are unusual on chapter header pages, but I have seen some books that place them there anyway. I recommend leaving running heads and folios off of chapter title pages. Whatever you do, do not place the folio in a different place on the chapter header pages than on the main text pages. The reader should be able to find the folios easy as they flip through pages of the book. If their location differs on some pages, they lose their utility. For this same reason, folios should never be placed near the spine.

Text LayoutThe text itself deserves the most attention. This is where the reader will spend the bulk of their time with your book.

All paragraphs should use left justified alignment. This is not the same as the default Microsoft Word setting of "left alignment." The full name of that setting is "left ragged alignment." It is called "ragged" because the lines don't necessarily fill all the available space in the line. In "justified" alignment, each line does, unless it is the last line of the paragraph.

Adobe InDesign and QuarkXPress will automatically hyphenate words when it would be unseemly to stretch or shrink the spaces between words too far. However, when the programs fail to make a good call, the justification can be modified by using shift+enter to insert a line break character manually.

Paragraphs that begin a new section of text should have no indentation. All other paragraphs should be indented. A good size for an indent will depend on the length of the line in your text block. For a 5.5" x 8.5" page with a typical text block, start with a 1 pica (one-sixth inch) paragraph indent and make adjustments until it feels right. The indent should be just big enough to be parsed quickly as a new paragraph but should not so large as to cause the reader to pause and gawk at it.

ConclusionI covered a lot of ground here, and there's still so much more I could talk about. I laid out the basics of what I've learned from typesetting, given four books as my sources, and walked through the basics of designing each kind of page for all the major sections of a novel.

I have turned comments on for this post, and as long as things stay civil, I'm happy to field questions or continue discussion there.

June 21, 2017

Lessons From Publishing, Part 1: Registering Works

Three and a half years ago, I set out on the adventure of becoming a publisher. Although I have shut down the economic entity representing my publishing endeavors, known as Fuzzy Hedgehog Press, the parts of publishing most interesting and valuable for me remain. As I discovered, those valuable bits have nothing to do with the operation of a business unit.

If, like me, you are a writer and publisher more interested in crafting literary art than in turning a monetary profit or becoming popular, then this series is for you.

Registering WorksAs a part of operating Fuzzy Hedgehog Press, I acquainted myself with the many ways it is possible to register writing with various economic and political entities. By the time I was shutting down my business, I had discovered that the most highly recommended form of registration was useless to me, and the most discouraged form was the one I should have been focusing my attention on all along.

Methods of registration differ depending on what country you reside in, especially in terms of cost. My examples are from the United States of America.

International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs)ISBNs serve a strictly commercial interest. They are the reference number that bookstores and distributors use to identify titles and their formats. Publishers that sell their books directly to customers exclusively through their own sales portals, like The Folio Society, don’t register ISBNs for their books, since they are bypassing bookstores and distributors.

Due to ISBNs' commercial necessity, online sources for independent authors and publishers tend to play up the importance of acquiring ISBNs.

In the United States, ISBN registration is operated by a company called Bowker. ISBNs must be purchased from the Bowker website and assigned to books using Bowker’s web portal. Each title must have its own ISBN (source). If the title has multiple formats, such as paperback, hardcover, ebook, audio book, etc., then each format must also have its own ISBN.

At the time of this writing, Bowker’s price structure is as follows: 1 ISBN costs $125, 10 ISBNs costs $295, 100 ISBNs costs $575, and 1,000 ISBNs costs $1,500 (source; all prices are USD). These prices represent a 25-50% markup from Bowker’s price structure when I was looking at ISBNs for Fuzzy Hedgehog Press three and a half years ago.

In Canada and some other countries, independent authors can apply for ISBNs from their government at no cost (source). No such government service exists in the United States at the time of this writing.

Having an ISBN is necessary to get your book carried with a distributor, and most bookstores will not order your book unless is carried by a distributor. The ISBN must be turned into a barcode and displayed prominently on the back cover of your book, along with the human-readable price (which you can also optionally encode into the barcode).

I am no longer interested in assigning ISBNs to my books, and, if you are also interested in writing and publishing for the art of it, and not the business, then I can’t recommend that you do so either. At the prices charged for ISBNs in the United States, you had better be certain that your book is going to turn a profit if you go down that road.

Library of Congress Control Numbers (LCCNs)The United States Library of Congress has been running the LCCN systems since 1898 (source). Public libraries and services like WorldCat use this information to categorize and organize books.

Some resources for independent authors and publishers mention LCCNs, and I’ve never seen it mentioned negatively, but advice in their favor occurs less frequent than ISBNs, probably because this form of registration is of unknown interest to bookstores, distributors, and vendors such as Amazon (their interest is probably very little).

However, getting one certainly won’t hurt sales, and, unlike the expensive ISBNs, there is no direct fee associated with LCCN registration. However, you must ship a single copy of the printed book to the Library of Congress upon its first printing (source). Ebooks are not accepted, and an LCCN will not be assigned to electronic-only publications (source).

Public libraries in the United States will order books based on readers making a request for the title. At some certain threshold of requests, a copy of the book is ordered. It will depend on the individual libraries’ policies, and these are opaque. I believe having an LCCN can only help libraries find a book, but I also believe that books do not need an LCCN in order for most libraries to be willing to make a purchase. The only way to find out about the threshold of requests necessary to result in an order being placed or other requirements for doing so (that I am aware of), is to ask the staff at a particular branch, and I would not expect individual librarians to be particularly forthcoming about such information.

I eventually came to the conclusion that libraries in the United States are operating nowadays much like bookstores: they are supplying customers with things that they want. Gone are the days when librarians helped shape public discourse by intentionally curating texts (if those days ever existed). I have little use for such a system in my current endeavors. I can recommend this method for others if they simply want one more copy of their book out there in the world, even if it’s just somewhere in the Library of Congress, but I wouldn’t count on this leading to any more or less visibility for your art.

Amazon Standard Identification Numbers (ASINs)Amazon maintains their own book identification system independent of both international standards and the United States government. Amazon assigns them automatically to both ebooks and print books when the author or publisher registers them for sale on Amazon.

Unlike ISBNs and LCCNs, ASINs do not typically appear on a book’s copyright page, either in independently or professionally published books. They are, however, a crucial component of a book’s Amazon URL (source).

Since Amazon controls an enormous portion of the print and ebook markets, most sources of information for independent authors strongly encourage selling their books through Amazon.

I no longer have any interest in participating with Amazon in any way. According to the fine print, any book registered with Amazon gives the company perpetual distribution rights to all portions of your writing anywhere within Amazon properties (“Amazon versus non-Amazon properties” is a distinction that is on the verge of meaning very little within the media realm; source). If you agree to these terms, I wouldn't count on maintaining any control over where and how your writing gets reproduced. Amazon is banking on the fact that most writers these days will just want to become popular and get paid royalties, and hence will be more interested in the scope of their book’s distribution than the manner in which such distribution is accomplished or the compensation such distribution should entitle them to.

The most fascinating element of this situation to me is that the dashboards indicating sales and book metrics are entirely owned and controlled by Amazon. They offer no receipts, no proofs of purchase, and everyone just assumes that these dashboards are displaying fair and accurate information. Color me paranoid if you want, but after reading through Amazon's terms of service, I have little confidence in the overall fairness of their system.

GoodreadsGoodreads is a social network for book readers. Readers mark which books they are reading and which books they have finished. Anyone can register a book on the Goodreads system for free (source). It is up to readers to mark that book as “reading” or “read,” or to perform various other social features with it, such as curating lists.

Advice for independent authors generally suggests adding a book to Goodreads.

I still register my books on Goodreads, and I have yet to find any reason not to, even reading the terms of service (general and writer-content specific). Registration does not necessarily entail handing over a copy of the book over to Goodreads, so they only get access to the publication metadata, which I'm happy to make public. That said, I keep an eye on those terms periodically, as Goodreads is a subsidiary of Amazon.

CopyrightRegistering for a copyright with the United States Copyright Office grants authors the means of legally enforcing distribution control of their work. Registration can be completed by filling out an online form and submitting a Word document or PDF copy of the work (source). Each work an author registers for copyright costs $35 USD at the time of this writing.

Online sources for information for independent authors are generally pretty negative about applying for copyrights. The crux of most arguments is that copyrights aren’t “necessary.” A variety of reasons are given, everything from not worrying oneself over the possibility of theft and illegal distribution, to copyrights being offensive to potential publishers (a very old-school variation on sales and popularity being more important than quality; source). Having been a publisher myself, I would be extremely skeptical of the motives of any publisher who got upset with me for possessing a copyright to my writing, and I certainly would never allow a publisher to copyright my work. Contracts from publishers should grant them distribution rights, not copyright ownership!

I now hold such sources of advice about copyright in contempt. In my opinion, copyright protection is the most important form of registration the quality-oriented author can engage in. It is not terribly cheap, but it is also not terribly expensive. It is also ideologically congruent with “art over profit.” Copyright is about enforcing the form in which your writing is presented to the world and demanding appropriate compensation when such presentation is enacted by a second party.

ConclusionI can no longer recommend ISBNs and LCCNs, since I see them to be of limited value. I discourage purchasing ISBNs on the basis of cost. I make no suggestion regarding LCCNs. If you can afford the single copy and the shipping, go for it, but don’t expect to get much for it, either. My stance toward Amazon and their ASINs is decidedly contrary. I am neutral toward Goodreads.

I highly recommend that independent authors register copyrights for their work.

March 26, 2017

Bellum Omnium Contra Omnes

The central sections of this review contain plot spoilers,Introduction

but the Introduction and Conclusion can be read without fear of exposure to major plot details.

At a company event, I was once asked to share a “guilty pleasure” as part of a team building activity. Others’ guilty pleasures included daytime television and Pokémon video games. Mine was, and remains, disaster movies–the more ludicrous the better. But this is not as clear cut a distinction as one might assume.

For example, while 2012 contains significantly less science-contradictory plot scaffolding than The Core, I would argue that The Core is the “better” disaster movie by dint of the way that every cheesy special effect, every poorly written line, every awkward mini-disaster hangs gracefully together in a coherent web of campy, absurdist contrivance. By contrast, 2012 is merely a sequence of catastrophic events, which fail to synergize thematically. I prefer my dreck to be well organized, thank you very much.

It is this sense of events’ interrelatedness and consequentiality that I feel is paramount to the construction of a disaster narrative. A still more successful narrative would tie the interconnected plight to some element of the human condition.

In my youth, I imagined that narratives of the apocalypse were somewhat new. The glitz of the big screen implies, through its dominion over special effects, that it owns the disaster narrative outright. I did eventually discovered the long tradition of disaster literature. J.G. Ballard wrote The Drowned World in the sixties, and George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides was written earlier still. However, it was with much delight that I discovered that apocalyptic fiction is at least as old as the science fiction itself. In 1826, Mary Shelley, renowned author of Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus, published The Last Man, the earliest apocalypse narrative of which I am aware.

The Last Man is the life story of narrator Lionel Verney. He and his sister Perdita begin their lives destitute, but through good fortune are brought into the company of a man named Adrian, one who would have been King of England, except for the fact that his father abdicated the throne in order to support the establishment of the first Republic of England. In Adrian’s company, Lionel and his sister are given access to education, philosophy, the arts, and most importantly, the social connections that will help them thrive as adults.

However, their happy lives are interrupted by a plague, which breaks out somewhere in Asia and quickly spreads across the globe. It is relentlessly virulent–one hundred percent contagious and one hundred percent lethal. Its victims lie dead within days of the onset of symptoms.

But what of the “coherent web” of interrelatedness and relevance to the human condition? The Last Man accomplishes much on this measure as well, for, unlike its modern silver screen incarnations, it is exceedingly philosophical and political at its core.

The English RepublicThe Last Man is set throughout the decade of the 2080’s. Shelley maps the social and technological landscape of the early nineteenth century directly onto this timeframe, for she appears to have exactly one major societal modification in mind. It was this long duration, the passage of nearly three centuries, from her perspective, that would allow the English to arrive in a social configuration ready to convert from a monarchy to a republic. And it is here I should note that England still is a monarchy in the real world, albeit a constitutional one with democratically elected members of parliament.

If we try to transport ourselves back to Shelley’s time, we will find our modern attitudes about the feasibility and sustainability of a democratic republic significantly diminished. The United States was, at that time, an agrarian nation only about fifty years old, and with some decidedly hypocritical, undemocratic tendencies, most notably the widespread practice of slavery. A survey of the rest of the world would turn up scattered monarchal powers dominating Europe and authoritarian or tribal conditions dominating nearly everywhere else.

It was a time much closer than us to the dawn of the Enlightenment, and in which the power of the church was more deeply entrenched and ideologically ingrained.

While the idea of an English Republic might seem a small skip of the imagination for the modern reader, in Shelley’s time, this particular novum demanded significant effort of her readers. It is unsurprising that she decided not to burden them with additional sociological and technological alterations.

However, this one vector of change is all that The Last Man requires in order to shine.

Early in the novel, we are introduced to Raymond, a noble member of Adrian’s social circle. Raymond is contrasted with his political opponent Ryland during an election in which both vie for the title of Protector (roughly equivalent to President in the United States, or Prime Minister in the modern United Kingdom).

Raymond wins and serves in this position until scandal forces him to step down. It is then that Ryland easily takes the Protectorship, and appears to hold the position well for over a year.

It is not long after this that the plague breaks out and begins ravaging Asia. Lionel draws out the details of the disease’s encroachment, as England loses its trade routes to Africa and India, then later Greece, then the disease is reported in southern Italy and France. As the certainty of safety inside the borders of England unravels, so does Ryland.

Ryland flees London and seeks the advice of none other than Adrian. Ryland ignores Adrian’s gentle persuasion that he lead the effort in curtailing the disease. Fearing for his own safety, Ryland instead insists on isolating himself in the far reaches of northern Scotland, in other words, as far away from the contagion as he can take himself.

It turns to Adrian to rally the country against the outbreak and ensure order and stability. This event is part of an undercurrent, which persists throughout the novel, a supposition that egalitarian and enlightened social organizational schema are dependent upon human flourishing. Under the pressure of diminished resources, natural calamity, and other stresses, such systems falter.

Do democratically elected officials really care about their constituents in the way that a nobility is impelled to, and acculturated to do so from birth? The insinuation of Shelley’s narrative construction vis-à-vis Ryland and Adrian seems to suggest not. And while one might be tempted to point out the corruption and decadence of various monarchal figures littered throughout history, we must also acknowledge that elections and republics seem to have done little to blunt the corrupting effects of concentrated power upon leaders. In fact, as the prevailing political order in the United States demonstrates (at the time of this writing), our duly elected leaders appear to be even more extreme forms of Ryland, not merely abandoning their constituents in a time of crisis, but willing to plunder the state of its remaining wealth while the world burns.

Despite Adrian’s enlightened leadership, England is further diminished by the plague’s continued onslaught. With a loss of critical mass of nobility, even monarchy falls away, at first to authoritarianism (specifically Adrian’s authority, although he is a benevolent dictator), and later tribalism, as religious and policy dissenters rise up against him and seize political control of their own small groups. Even these social orders, crude as they may be, are each in turn leveled by the plague.

Eventually only Lionel, Adrian, Lionel’s son Evelyn, and Raymond’s daughter Clara remain alive.

Love in the RuinsAnd yet, though the plague has passed, other misfortunes befall Clara, Evelyn, and Adrian, eventually leaving Lionel entirely alone. The final portions of the novel are among the most chilling. Lionel is confronted everywhere with the remnants of humanity—banquet tables fully set, but with all the food reeking of multiple years’ spoilage. Even the great works of Rome, the Coliseum and great museums, mock his loneliness. The former joy and energy he had found in the intellectual depths of philosophy, art, and literature, have all become sour reminders that he is alone.

Seeking to find whatever meager companionship he can manage, he attempts to feed a family of deer, but even the beasts of the forests spurn him. He eventually befriends a sheep dog, but his internal monologue makes it clear that such animal bonds are no replacement for human ones.

Lionel’s plight begs a deeper question, one especially relevant for our modern day, some two centuries after Shelley. We move through the modern world in pursuit of acquisition—more time, more possessions, better job, better accomplishments—more, more, more. Ironically, at the end of the novel, Lionel Verney has everything. He pointedly draws attention to the fact that all the world’s granaries, libraries, and museums are open to him. He wants not for food, for health, nor even for time—he has no obligations nor duties and his entire life lies ahead of him. Having lost all political bonds, including individual relationships with his most beloved family and friends, Verney is now perfectly free and simultaneously perfectly oppressed, for how can any of his great works be great if there is no one to appreciate them? Why bother appreciating another’s great work without a companion to share in the experience and help make sense of it?

Perhaps, at the end of leveling all the social strata and doing away with oppressive systems, we end up back where we started, a perfect infinity of freedom and oppression collapsed into one. We end the novel wondering which would be worse, the achievement of “utopia” or the utter destruction of social bonds, or perhaps each is its own kind of hell.

ConclusionThe Last Man surpasses your average disaster narrative. By eschewing a contrived scientific or fantastical “victory” climax in the form of a cure for the plague, the novel treads more interesting water by letting everything collapse completely and inspecting what remains of the human condition in the disaster zone.

As our own modern world staggers forward, perpetually demanding ever more extreme forms of individualism and personal liberty, it might be sobering for us to reflect on the questions posed by the philosophers of supposedly “simpler” times. Our resources and infrastructure can bear the weight of our prevailing social order… for now. If last year taught us anything, it’s that perhaps we are in for just such a lesson as was encoded by Mary Shelley in The Last Man nearly two centuries ago.

February 16, 2017

Write Anyway: A Dialogue

They tell me I can’t write.

Write anyway.

Well, not that I can’t. That I shouldn’t.

Same answer. Why do you even trust this “them” anyway?

My stories weren’t selling on Amazon, so I found a local writing critique group and started submitting segments to them. They meet in person once every two weeks, sit around a table, and each person takes a turn talking about everyone else’s writing. They seem like they know what they’re talking about.

What kind of changes do they tell you to make?

Well, the biggest problem is that my stories don’t have enough action. It means that I don’t start the story in the right away. That I don’t capture the reader’s attention in my opening paragraphs.

Ah. Yes. “Action.” This is a word that, when it comes out of a critiquer’s mouth—especially a writer-critiquer’s—you should nearly always cease paying attention to them.

But then… won’t my writing be boring?

Maybe.

Isn’t that a problem?

Probably not.

It’s not a problem if my writing bores people?

Sort of. It depends who you’re boring. Let me ask you this. Have you heard of a guy named Chuck Tingle?

Uh, yeah. That’s the Dinosaur Billionaire Forced Me Gay guy, right?

Yup. Do you think it’s possible to read his work and be bored?

Probably not.

Right. Lots of action. Of the sexual variety. How many neurons do you think it takes to comprehend his work on an intellectual level? Are there nuances of emotion and character to appreciate? I can see you’re choking on your own laughter, and I think you’re beginning to understand.

So… “action” isn’t necessarily good?

Right.

But there are these other writers in my writing group who tell me it’s the most important—

Stop listening to them!

What about “tension?” Is that nonsense, too?

Yes. That’s code for using plot to create the kind of “surprising” situations that will only surprise readers who aren’t paying very much, or any, attention to the narrative. It’s sad how easily dumb people’s emotions are manipulated.

Whoa. Dumb people? Isn’t that elitist?

Yes.

Wait. You’re advocating my writing be elitist? That I be elitist? I don’t know if I’m comfortable with that.

To some degree, yes. Here’s the alternative: You have to accept that Space Raptor Butt Invasion is equally legitimate literature as, say, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus and The War of the Worlds. If you believe that they’re not, that we should build ourselves a literary framework that allows us to dismiss Space Raptor Butt Invasion as garbage while privileging Shelley, Wells, and other writers who have withstood the test of time and hundreds of thousands, if not millions of readers’ scrutiny across multiple centuries, then yes, you have to be at least a little bit elitist. Allow me to be even more stark about this, using an example from very recent history. This insane, postmodern mindset of aesthetic relativism, which allows the complete dismissal of the authority of both standards and experts, has just four months ago allowed sixty-three million odd people to vote against the continuation of the democratic republic as a form of government in my country. Terrifyingly, these individuals are not even aware of what they have actually done, because aesthetic relativism has allowed them to insist that all evidence that correctly depicts reality is a lie. The end result of any mindset which allows such complete and total relativism will be a fantasy world in which the absurd and grotesque demand more significance and attention than that which is legitimately good and uplifting. The believer will end up debased by his own insistence that he is right, and that the world must agreeably conform to how he believes it should be. So yes, I’m going to insist that you be at least a little elitist, as well as suggest that you will be better off as a writer if you start ignoring this ridiculous claptrap about “action” and “tension.”

Anything else you want to add to list of banned writer advice?

Well, one more, but it doesn’t have a sexy nomenclature like the other two. It’s rather context specific: if a reader tells you that they didn’t like a thing, but their explanation makes it clear that they are using only their emotional reaction as the foundation for their opinion, just ignore, ignore, ignore. This phenomenon is all over our culture in spheres beyond literature and art. It’s really hard to find any other kind of opinion, actually. Within literature, this phenomenon is frustrating, because most writers these days have read hardly anything at all. And this isn’t even genre-specific. It’s as much a problem in sf as anywhere else.

Okay, Mr. Smarty Pants. If you’re so awesome, what kind of feedback should I be soliciting?

Intelligent feedback.

That’s rather subjective.

Yes.

Wait! Now come on. This is just too much. You go on this long, self-important spiel about the inanity of aesthetic relativism, and you follow that with the assertion that I should search for feedback that demonstrates some “intelligence” quality which you openly admit is subjective?!

Yes.

Well, I guess I’ll just sit here patiently and wait for you to resolve the obvious paradox.

The paradox doesn’t have a resolution.

…

Our entire world is an irresolvable paradox. Endlessly pushing freedom and liberty causes their effects to fold back in on themselves into authoritarianism and oppression. In order to be good at leading, you must be good at serving others. In order to gain true power, you must be truly humble. In order to be wise, you must admit that you know nothing. The person giving you feedback is giving intelligent feedback when she is certain that she is right, but simultaneously open to learning about what you meant when you wrote what you did. She brings her own viewpoint to your work, but tries, for some brief period, to meld it with what you put into your words, and then she steps back, looks at that brief merger, and evaluates it against everything else she has ever experienced. The more other books she brings to her side (from her experience) and the better those books are, the better will be the resulting feedback, and that goes for your side, too. That’s why writers have to read. Every book you read with your attention fully engaged makes you a better writer (and probably a better human being, too). And it’s not enough to simply scan your eyes across hundreds of thousands of words, as I’m convinced most people these days are doing when they “read.” In order to have a more intelligent viewpoint, you have to actively engage. And you will never be done. There is always more human experience to explore. You will perpetually know nothing, but your opinion will rise in legitimacy relative to others over time.

This all sounds very dubious. Can you point to any piece of research, any evidence, anything else that can back up your case?

No. And I’m not interested in doing so. Mostly because this is all stuff that I feel is best (and probably only) learned from experience. This is why undergraduate literature programs are often of the format, “read a bunch of this stuff that your professors know is good and then talk/write/think about it.” The only way to really understand a good approach to literature is to experience it for yourself.

Do you have a PhD in Literature at least?

I have a BA in English Literature I got about a decade ago, which I got mostly B’s in.

Forgive me for being so blunt, but it doesn’t sound like you were very intelligent yourself back then.

I wasn’t. In fact, I was a giant idiot until about age thirty.

Why should I trust you now?

You shouldn’t. Not blindly anyway. You’ll have to arrive at your own truths. I can’t help you there. This will either resonate with you, or it won’t. The same way you can either choose to believe that climate change is real, a discernible condition, the inevitable conclusion of all evidence around you. Or you can make up your own evidence and believe whatever you want. Like that it’s a hoax invented by the Chinese government. Or the work of space raptor butt invaders with ice-sheet-melting flame throwers. And that Chuck Tingle’s writing is the emergence of a new literary form, which we can tell is legitimate because so many people are paying attention to it. Is my sarcasm coming through?

Loud and clear. While I might agree with this last point at least, I don’t think you’ve helped anything by elaborating all of this. In fact, I think you've made everything worse. I don’t know who to trust anymore!

Good. Don’t trust anyone. Most especially me. But if you now suspect people who want you to load your writing up with “action” and “tension” and omit any detail that their limited minds aren’t capable of comprehending (these people are toxic), well, I’ve made the world a little bit safer for literary complexity, and I think that is worthwhile. Perhaps, just maybe, you yourself might consider following the advice of the guy who wants you to discover your own difficult, paradoxical truths, rather than follow a bunch of dubious, rote claims about the proper structure and form of literature. Here’s a great exercise for you: get this writing group of yours to make a list of about half a dozen books whose writers they think follow the advice they espouse, then survey the results and ask yourself how individual those authors’ voices sound, how differentiated they are structurally. Ask yourself if you really want to force yourself to sound this way on the page. I went through one such exercise, and I found my list’s books appallingly similar and limited in cognitive scope. A complaint from a critiquer that your writing is “boring” is usually a compliment. It means you’ve crafted something too complex for a dumb person to comprehend.

But… If my writing’s boring, no one will read it.

No one? Or just people who fail at paying attention to the most basic of narrative details?

Well—

How about just people who find their attention wandering after two pages without a sex scene or the graphic depiction of a dismemberment to keep them interested?

But, um—

How about just people who will refuse to engage with any stories that fail to reconfirm, in fantasy form, their own simplistic views of the world and their place in it, a reflected world, which shamelessly indulges and aggrandizes the reader’s ego? How about just people who want their literature to be an opiate and aphrodisiac, rather than a gateway to expand their cognition?

That last argument sounds a lot like the one made by proponents of literary realism as the only valid genre.

It’s similar, sure. But their assertion is the scary, extremist opposite of aesthetic relativism: aesthetic authoritarianism. There is some truth to the realist’s claims that sf is self-indulgent and vulgar, at least with regards to some individual works. They are wrong when they try to make claims about the entire genre aesthetic on this basis.

I see. This is that whole “some elitism is okay” thing, right?

Yes.

So, I should ignore the people who tell me to add more “action?”

Yes.

And ignore the people who tell me to add more “tension?”

Yes.

And I should read a lot, and find other people who read a lot, and we share our writing, and we learn from reading each other’s writing by reading it and talking about it?

Yes.

And we don’t talk exclusively about how we emotionally respond to writing, but a composite of how we intellectually and emotionally react, using everything we’ve read before as a framework?

Yes.

Most people will ignore me.

Yes.

They’ll tell me I’m boring.

Yes.

They’ll tell me I can’t and shouldn’t write.

I know. Write anyway.

February 12, 2017

The Shining City in Shambles

The central sections of this review contain plot spoilers, but the Introduction and Conclusion can be read without fear of exposure to major plot details.Introduction

Science fiction has a very long tradition of societal critique. Although the genre modes with the most currency in the popular culture – space opera and high fantasy – are overwhelmingly asocial, the tradition of social exploration in SF goes back to Shelley by way of Atwood, Huxley, Orwell, and Wells. The dystopian/utopian subgenre is all about raising the reader’s awareness of society’s present state, so as to bring about greater justice, or at the very least avoid a future darker than our present day.

I have been well aware of the above writers for many years, as these are the ones most commonly talked about vis a vis SF utopias and dystopias. Two years ago, I happened upon a book on the Folio Society website by J. G. Ballard called The Drowned World. After a bit of research, I discovered I had unknowingly already been exposed to one of his works in movie form, The Empire of the Sun, and I promptly picked up some of his most interesting-seeming novels – Kingdom Come, High-Rise, The Unlimited Dream Company, and Hello America among them.

My reading list being what it is, all of these titles remained in the category of “many years out,” and until 2017, my first Ballard novel was slated for 2020. However, the recent political events in my country prompted me to search out literature that examines the American condition, and this caused me to move Hello America into an early 2017 slot.

The novel’s action is set in the early twenty-second century, a time in which climate change has rendered the majority of the North American continent uninhabitable. A group of European explorers, descendants of US refugees, return to America a century after their ancestors left, and begin a cross-continental expedition, whose challenges and discoveries call into question some American values, while exulting others.

Hello America was published in 1981, but my Liveright edition includes an introduction written by Ballard in 1994. He writes, “[a] curious feature of the United States is that this nation with the most advanced science and technology the world has ever seen, which has landed men on the moon and created the super-computers that may one day replace us, amuses itself with a comic-book culture aimed for the most part at bored and violent teenagers. … Nonetheless, as the reader will find, Hello America is strongly on the side of the U.S.A., and a celebration of its optimism and self-confidence, qualities that we Europeans conspicuously lack.”

Hello America accurately depicts the best and worst of American culture through its dystopian lens, and the depth of that analysis far exceeded my expectations.

The Forty-Fifth PresidentBy the middle of the twenty-first century, the United States of America has been abandoned. The Russians dam the Bering Strait, and climate change advances rapidly across the North American continent, turning everything east of the Rockies into a parched desert and the West coast into a tropical rainforest. By the early twenty-second century, America is merely an idea, an antiquated memory in the minds of American descendants living throughout Europe.

North America itself remains ignored – until scientists begin picking up atmospheric radiation spikes, and trace them back there. Worried that old nuclear reactors, or worse, weaponry, is malfunctioning, The American University at Dublin sends a team to investigate the continent.

Our narrator for the expedition is Wayne, a gregarious, idealistic, early-twenties stowaway, who dreams of rebuilding American society, restarting the American industrial engine, and, quite shocking to the ears of a reader in 2017, he articulates this desire most succinctly, as that of “making America great again” (158).

His ambitions are at first held in check by the political hierarchy of the scientific expedition. He is kept aboard the ship when they first arrive in New York, but after the ship is beached (due to an accidental run-in with the underwater torch of the Statue of Liberty), he is given more and more responsibilities. Eventually, he finds himself guardian of the water distillation equipment on a horseback expedition from New York City to Washington D.C.

Most of the ship’s crew loot the dead cities for profitable memorabilia, but Wayne has loftier goals. Once in D.C., he seeks out the Washington Monument, the National Mall, and most tellingly, he cleans out the Oval Office, wipes the graffiti off its walls, and digs the Lincoln Memorial out of the hills of sand that have surrounded it.

As the expedition soon learns, America is not completely abandoned. Some people have remained, and roam the desert in tribes. Most of these are shades of various socio-economic groups we would find recognizable – executives, professors, bureaucrats, astronauts – all reduced to a few hundred illiterate nomads done up in the costumes of their ancestors.

Another nuclear strike occurs in Boston, driving the expedition further West, through the vast desert, and toward the Rockies, where they discover the source of the nuclear detonations. In a lit-up Las Vegas, covered now in jungle vegetation, a man calling himself Charles Manson, a member of a prior European expedition (all of whom were presumed dead) has set up a small enclave of civilization and declared himself the forty-fifth president of the United States.

From the onset, Wayne is wary of President Manson, who speaks of a “plague” arriving on the East Coast from Europe, one which can only be contained by dropping nuclear missiles on the affected cities. His citizens are disaffected teenagers, who seem interested in allowing him to rule mostly because he lets them play with guns and helicopters, and smoke pot in their free time. While this does not instill Wayne with confidence, he goes along with Manson’s plans upon being offered the vice-presidency. Wayne hangs his dream of leading America to a brighter future upon Manson’s hook, and that job means managing Manson’s very dangerous and erratic impulses.

Elitism and Xenophobia‘We need people with the highest skills—computer specialists, systems analysts, architects, agronomists. For the first time in history we’ll be recruiting an entire nation using the personnel selection techniques perfected by Exxon, IBM, and DuPont. … We’ll take only the best because America needs only the best…’

…

Only Anne had objected, frowning with some surprise at this impassioned speech. ‘But, Wayne, that’s an incredibly elitist viewpoint. What about those tired, huddled masses, yearning to breathe free…?” (162)

As a nation focused intensely on individual achievement, individual responsibility, and individual liberty, we have often found it difficult to correctly balance these very noble imperatives with the necessity of caring for society’s weakest and most vulnerable members. Quite ironically, we often forget about creating equality of opportunity for the disadvantaged, a goal which tends to get lost in the glare given off by the needs and wants of our best and brightest. That individualism often gives these best and brightest inflated egos does nothing to help the matter.

However, as Anne rightfully points out, the necessity of creating that equality is written into our DNA as a nation. We cannot shrug the value off when it becomes inconvenient, as much as we, and Wayne, might like to.

As Wayne’s role as vice-president proceeds, he discovers a second survivor of Manson’s expedition, a Dr. Fleming, who has been holed up in the Las Vegas Convention Center and is constructing animatronic robots of all forty-four American presidents. It is Fleming who reveals the real reason for the East Coast nuclear strikes.

‘But Dr Fleming,’ Wayne insisted, ‘[President Manson] was forced to destroy those cities. The plant and animal life in the New World have lost their resistance to Old World bacteria.’

‘Is that what Charles told you? … Yes, there’s certainly a deadly plague on the way now—it’s very virulent, and there’s no known antidote.’

‘You know about it?’

‘Of course. It’s the most threatening disease of all. It’s called “other people.”’ (183)

The “disease” President Manson is so worried about is not a disease at all, but a thin veil of an excuse for building a wall of radioactivity between Europe and the Rockies.

At our worst, we Americans can lead ourselves to believe that our strength comes from the ability to control a zone of land and keep others out, rather than our ability to stitch together a complex social fabric out of pluralistic consensus-formation – e pluribus unum. We have repeated xenophobia throughout our history, at times targeting races, most blatantly and exploitatively with African Americans, but also with immigrants from Italy and Ireland. Religion has also been also a vector, with Catholicism in the past and Islam today.