Matthew Buscemi's Blog, page 24

January 21, 2019

New Editions Released

In February of 2016, I sold out of all my paper copies of Voyage Embarkation and Insomnium. I ran out of Alterra later that same year. By that time, I was already toying with the idea of shutting down the press, and I wanted to redesign the covers of those books, anyway. I also knew that Voyage Embarkation needed a textual overhaul before I would consider republishing it. As a result, I ended up leaving those books out of print.

I decided to shut down Fuzzy Hedgehog Press in November of 2016, and with it went the Amazon availability of all the rest of my first editions: Lore & Logos, Schrödinger’s City, Transmutations of Fire and Void, Adventurers of Opytt, and Beyond the Hedge Volume 1. The novella I wrote in November of 2016, Our Algorithm Who Art Perfection, never got print published anywhere, except for a one-of-a-kind edition I had printed as a gift to my husband.

As of today, most of these books are back on Amazon, and with snazzy new covers:

One of my behind-the-scenes projects during my long blog absence was a mega-overhaul of Voyage Embarkation’s text. When I first decided to sit down and really write Voyage in 2011, I went searching for writing groups. Most of the groups I found were abysmal in quality (there were a few exceptions), and being relatively naive in 2011 and 2012, I ended up absorbing and incorporating a lot of very bad feedback into Voyage Embarkation’s first edition. During 2017, I completely reworked the novel’s first five chapters and affected other heavy edits throughout the rest of it. The plot structure is still essentially the same, but stylistically it should feel much more consistent with my later writings.

I’m generally not a fan of that kind of thing. I could probably do something very similar to Insomnium or even Alterra at this point, but in those cases I would prefer to let the original text stand. That’s because even though the voice there is less developed, at least it’s mine. The thing that really started to bug me re-reading Voyage was that it sounded too much like a hodgepodge of voices from my former writing group. That had to go.

Insomnium, Alterra, and Schrödinger’s City are largely unchanged; I made only minor edits here and there.

Transmutations is my new, definitive early short fiction collection. It contains the best stories of Lore & Logos and Transmutations of Fire and Void, organized thematically, and with new commentaries at the beginning of each thematic grouping. I also included the novella Our Algorithm Who Art Perfection, making it available in print for the first time ever.

All of these books are available as paperbacks and for Kindle both. You can find the Amazon links to my books on the new ‘Books’ section of this website, and also on my Amazon author page.

Next StepsI have some unpublished stories sitting around that I am working on getting into publishable shape. In 2015, at one of the good writing groups, I sat down to write, and I found myself instead sketching out an archipelago and placing city-states upon it. Out of that came six stories—one flash fiction, three short stories, and two novelettes—set in the world of Palípoli. These will be released soon as The Shipwright and Other Stories.

Another novel has been brewing in my mind, one inspired by both Palípoli and my recent excursion into Classical literature (specifically Herodotus’s Histories and Thucydides’s The Peloponnesian War). In my novel, three writers, each separated by a thousand years, attempt to narrate the history of a war, but each brings their own distortions to the events, and much to their dismay, the distortions begin to cross timeframes, further disrupting each writer’s ability to form a coherent narrative. Even more disturbingly, the distortions begins to steer the war, which was won, toward being a war which was in fact lost, an outcome that would have disastrous consequences for all three characters’ civilizations. The working title is The True History of the Ksezian War. It is in the drafting phase.

January 12, 2019

SF is Already High Literature

I have just finished Andrew Milner’s Locating Science Fiction, which was a wholly useful and insightful as well as a fully frustrating book. Milner devotes many pages to expounding upon various cultural artifacts of an enormously wide range of qualities (for example, the first chapter contains a protracted analysis of “Dan Dare,” a kind of British Flash Gordon, while the sixth chapter contains an exploration of Orwell’s reaction to Huxley and Zamyatin). Milner is responding to the now-famous derision that SF generates within certain circles of the literary establishment. He even goes so far as to codify how the literary establishment treats SF (67).

This, in my opinion, is wrongheaded. I, personally, understand the frustration of being in an academic setting where the works I valued were being undervalued by the establishment. I experienced as much, and with regards to SF as well, during my own undergraduate career. Milner has responded the way I once did, by grasping at relativism, in order to undermine the legitimacy of the structures of power.

The logic goes like this. Literary scholars are wrong in their sweeping generalization of all SF being bad, therefore all SF and all literature must be equally valuable. Milner has taken this a step further with the help of postmodernism via Max Weber. All acts of “valuation” are merely acts, and there is no inherent value to anything (179).

This, to me, is going much too far. SF literature is a subset of literature generally speaking, regardless of what any particular member of the academy thinks. Also, there exists a lot of bad SF writing and a lot of bad realist writing. It does no one any good to pretend that we live in a value-free world that merely contains lots of writing, one where we set Dan Dare comic books alongside Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We for serious consideration.

Milner’s definition is, “SF is a selective tradition, continuously reinvented in the present, through which the boundaries of the genre are continuously policed, challenged and disrupted, and the cultural identity of the SF community continuously established, preserved and transformed. It is thus essentially and necessarily a site of contestation.” (39-40) In other words, SF is whatever all the random people of the world identify it to be. Any challenge to the existing norm, no matter how blinkered or ignorant, gets fully absorbed into SF by this definition.

I do not like constructionist definitions. In my opinion, literary critics should do more than merely survey the vast conglomeration of human creative output and make value-free observations. Intelligent experts need to set boundaries, clearly delineating the good from the bad, discerning what is common to both, and engaging in analysis of works that are both critical of the work being analyzed and of the critical theory itself. (The “of the critical theory itself” part is extraordinarily difficult, which is why we have so many academics who wrongly believe that SF has no value.) This is what it means to generate a definition of a literary genre. This is what is means to do literary criticism. To accept a definition such as Milner’s is to eschew that responsibility and collapse all distinctions, and that is simply not a worldview I accept.

Form and ContentOne portion of Damien Broderick’s definition of SF is, “[a] de-emphasis of ‘fine writing’ and characterisation.” (Broderick, 155) In the same vein, Milner writes that, “the binary between Literature and popular fiction is almost entirely an artifact of Literary modernism, designed to valorise form over content, and cannot be applied to SF, which, by contrast, is a genre of ideas and therefore privileges content over form.” (Milner, 14)

These claims also go too far in that they attempt to push SF aesthetically out of literature entirely. Writing of poor form cannot be literature anymore than the category ‘cat’ could be reclassified as not belonging to animalia on the logic that meowing is “un-animalistic.” Either an unnatural redefinition of SF/cat is taking place, or, the proposal is a radical redefinition of literature/animalia. In Milner’s case, I understand his proposal to be the latter. He is not just attempting to classify SF with this proposal; his is attempting to redefine the boundaries of literature entirely.

The topic of “form and content” in literature is extraordinarily complex, and I could devote hundreds of hours of research to its exploration. Suffice it to say, both are crucial to any conception of literature. To relegate one or the other to lesser- or non-importance constitutes a radical re-imagining of the boundaries of literature itself.

I personally hold my SF to high standards. I have limited time in my life to devote to art and literary research. I do not want to waste it on anything but the best. I demand rigorous attention to form and content from the authors of everything I read, SF and non-SF alike. If I, a professionally unpublished independent author and scholar can maintain such standards, I expect those supported by research institutions to do so as well.

SF and PoliticsEver since Darko Suvin’s Metamorphoses of Science Fiction, SF studies have been bound up with Marxist literary criticism. This is another of the critiques leveled against Suvin, that his definition turns SF into a kind of literature of utopian struggle. (Milner, 179)

In this, I would tend to agree with Milner. Suvin’s definition is too narrow in precisely this sense. The themes and motifs of a novel can reach toward the Good (in the virtue ethics sense) without forwarding the Marxist agenda, much as Marxist might like for the two concepts to be conflated. My only difference with Milner on this point is that I would exclude works that are either vulgar, or which reach elevate the Bad instead of the Good. Milner indicates that he would include the former (179), and I suspect that he would categorically reject the existence of the latter.

The History of Science FictionMilner devotes an entire chapter to discovering the origins of SF. Milner agrees with the conception common in SF literary studies, which is that SF begins with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. He rejects Darko Suvin’s and Adam Roberts’s proposals, which is that SF has a much longer history. As their proposal has it, in pre-industrial times it expressed itself in the form of the fantastic voyage to faraway lands, a tradition that reaches back into antiquity.

Milner writes, “Borrowings from Shakespeare or Lucian or More can be important and interesting, but they are borrowings from outside the selective tradition of SF, nonetheless.” This is because SF, “is a ‘type,’ that is a radical distribution, redistribution and innovation of interest within the novel and short story genres. … [T]hese innovations of interest were focused above all on the practical capacity of sciences to become technologies and that they first occurred only in the early nineteenth century.” (153)

This is one of the many points at which Milner contradicts himself. He has already established a constructionist definition of SF. By his own definition, the fact that Suvin and Roberts have claimed The Tempest, A True Story, and Utopia to be part of the SF tradition, they gain some small amount of SF-ness. If Milner had set out a binary or a multivalent definition, his argument would hold some weight, but it is defeated by his own desire to be inclusive of elements of the genre which he feels have been unfairly dismissed.

Milner’s definition qualifies Suvin’s and Roberts’s proposals as “transforming the cultural identity of the SF community.” His arguments against them hold no weight under the parameters of his own methodology.

RelativismIn the end, I would call my experience with Locating Science Fiction more perplexing than anything else.

On the one hand, I find myself awash in some extraordinary insights. I will almost certainly come back to it for its segments on Zamyatin, Huxley, and Orwell, and its exploration of Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of the cultural field, which are among its best portions, and it contains a myriad of minor insights.

However, I cannot help but quote what I find the be the work’s most glaring self-contradiction. “… I certainly do not mean to suggest the kind of relativism that became de rigeur during high postmodernism, only that what Eagleton says of literature in general is also true of SF in particular: ‘There is no such thing as a literary work or tradition which is valuable in itself … “Value” is a transitive term: it means whatever is valued by certain people in specific situations.’” (179) It may not be the relativism of high postmodernism (which, I admit, I am ill-equipped to assess), but Milner proposes relativism enough to seriously undermine any potential coherency of what he means by the term ‘SF.’

Next StepsAs mentioned previously, I’ll be collecting up reviews of Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr.’s Seven Beauties of Science Fiction and doing an analysis of those.

ReferencesBroderick, Damien. 1995. Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction. London: Routledge.

Milner, Andrew. 2012. Locating Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press.

January 7, 2019

A Typology of SF Definitions

This is not the post where I will be exploring Andrew Milner’s book. I’m still planning on writing up a summary of my thoughts on his book Locating Science Fiction, but for this post, I’d like to elaborate on the typology of SF definitions I created in my last post, which I admit was rather ad hoc. It would be good to give that typology some detail.

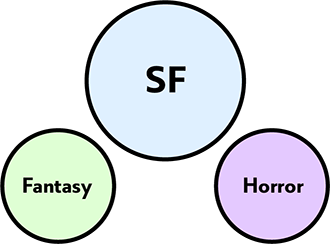

The Binary DefinitionDarko Suvin, Robert Scholes, and Adam Roberts have all presented what I call binary definitions of SF. The definition proposes boundaries that determine whether a given work is SF or not SF. Here is a visual representation of this style of definition:

Of course, such definitions will be susceptible to the critique that they elevate SF above other genres, that they do not allow for hybrid genres, and that they do not allow for a work to contain elements of multiple genres.

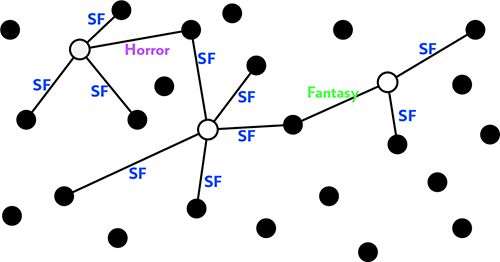

The Constructionist DefinitionPost-modernism provides a solution to those problems. This leads us to the SF definitions of Damien Broderick and Andrew Milner, which I term constructionist. Here is an illustration to represent a constructionist definition:

Notice that the field of all eligible works is now the visible universe (rather than just works of literature), and, crucially, SF is not a delimited field containing the works, but rather SF is defined as the connections between works. The connection lines represent instances of an individual identifying a thing as SF (or Fantasy, or Horror). So, if I point at a copy of Wuthering Heights and call it SF, under this definition, it gains some small amount of SF-ness. I could also point at a map of Zimbabwe and call it SF, or a twelve-year-old’s illustration of her pet cat. It doesn’t matter what the thing is. What matters is how individuals identify it.

A constructionist definitions makes hybrid genres and multiple genre identification possible.

The Multivalent DefinitionIstvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr. proposes a definition of SF of a type I call multivalent. Rather than a single litmus for SF-ness (ala binary), a multivalent definition proposes many litmuses. The definition therefore allows for SF to exist on a spectrum, as illustrated below.

The multivalent definition is still normative, like the binary definition. However, the multivalent lacks the firm boundaries of a binary definition. Further, it is presumed that related genres project similar fields, and in this way, the spectrums of SF, Fantasy, and Horror can overlap.

My AnalysisI find the binary definitions I have encountered useful in as much as they attempt delineation, and while I agree with the constructionists’ sentiment that the binary delineation is unnaturally limiting, I find that constructionist definitions problematic in that they lack limits. Without any limits, we arrive at the situation where anything can have any meaning, ergo nothing is capable of really meaning anything.

The multivalent definition neatly avoids both of these problems. Works can be SF, not-SF, but also partially SF or somewhere between SF and other genres. A critic might argue that the delineation of many vectors or “beauties” makes such a definition overly complex, and therefore more troublesome than it’s worth.

Next StepsI’ll be searching out reviews of Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr.’s The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction soon, so that I can see what critiques of this approach have already been made. In the meantime, I’ll be finishing up Andrew Milner’s Locating Science Fiction.

January 6, 2019

SF as Constellation

So far, all of the definitions I have explored have fallen into one of two categories: binary and constructionist. Darko Suvin provides a binary definition; it divides works of fiction into two categories. They either possess sufficient “cognitive estrangement” or they do not. In this way, works can be classified as either SF or not-SF. Damien Broderick’s definition appears constructionist (note that at the time of this writing, I am still limited to what Adam Roberts has written about him). According to Broderick, SF comes into existence as a web of inter-related works, whose SF-ness is defined by those relationships.

In The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr. proposes a third kind of definition. His is multivalent. Csicsery-Ronay identifies seven vectors (or “beauties”), which each act as a kind of science fictional litmus. A work can be simultaneously strong in one vector and weak in another. Works of fiction are no longer judged as either “in our out” of SF, but rather occupying a spectrum of SF-ness, depending on how many beauties they exhibit and how strongly they exhibit them. The beauties are:

Fictive Neology

Fictive Novums

Future History

Imaginary Science

The Science-Fictional Sublime

The Science-Fictional Grotesque

The Technologiade

The ConstellationFictive Neology is the invention of new words to signify the altered reality of the science fictional world. For example, the many components of Newspeak in George Orwell’s 1984, such as “Ingsoc” and “doubleplusgood,” are examples of neology.

Fictive Novums is essentially a reiteration of Suvin’s definition of the novum, with a few important exceptions. Csicsery-Ronay attempts to free the term from its Suvin-endowed direct association with utopianism (The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction, 54). Also, whereas Suvin was adamant that a good SF text should only have one novum, Csicsery-Ronay is quite happy to accept multiple nova (61-5).

Future History involves the reader extrapolating a history from his real moment in time up to the time of the future setting of the novel. Alternatively, it could be that the reader must extrapolate the history of an altered timeline rather than a future one, with the fiction’s divergence point from the real world timeline serving as the base. Therefore, a story strong in “future history” does not necessary need to take place in the future.

Imaginary Science, as the name suggests, involves the presence of technological artifacts that have not been invented in reality. They do not necessarily need to be continuous with real science as known to the reader of the text. They need merely to produce a “cognition effect,” a modification to Suvin elaborated by Carl Freedman in Critical Theory and Science Fiction. For details and a justification, see the previous post’s section on hard and soft science fiction.

The Science-Fictional Sublime is a sense of awe and wonder at the ordered and beautiful magnitude of some element of the fiction. In space adventures, this usually manifests as exotic space phenomena. In mystical or quasi-religious SF, sublime elements manifest themselves as (usually technologically mediated) manifestations of God. This element is often the bridge between fantasy and SF.

The Science-Fictional Grotesque is the inverse of the sublime. Whereas the sublime is the epitome of order and beauty, the grotesque is the manifestation of chaos and horror. Epistemological boundaries break down in the grotesque’s wake. The best examples are the many demonic creatures of Lovecraftian fiction. See also anything written by Edgar Allen Poe, such as eviscerated hearts that still beat beneath floorboards. This element is often the bridge between horror and SF.

The Technologiade is a term invented by Csicsery-Ronay. It identifies a type of plot structure that he describes as a technologically-inflected Robinsonade. In other words, a high adventure, “quest for the grail,” or colonial-style adventure to new lands, but with a science-fictional setting and addressing science-fictional concerns.

Comparison to Prior DefinitionsThis “constellation” style of definition solves many of the quandaries that have vexed science fiction literary critics since Darko Suvin introduced his binary definition of “cognitive estrangement generated by the novum.” One piece of criticism was that his definition too narrowly focused on utopian literature. Another was that it excluded fantasy, horror, and other genre interplay with science fiction entirely.

Csicsery-Ronay’s definition solves both of these quandaries. Utopian SF will be necessarily strong in its Fictive Novum and Future History, and can utilize the other beauties as it sees fit. Fantasy-inflected SF will probably take advantage of some combination of Neology, Sublime, Future History, and the Technologiade. It will probably ignore Imaginary Science, but under this definition that’s okay. A work is now allowed to be science fictional to a degree, rather than wholly in or out of the genre.

My ThoughtsThe Seven Beauties of Science Fiction is the first work of SF literary criticism I ever read, so if my analysis seems less involved, that’s only because I’m returning to it in review. This is the book that sent me off searching out Darko Suvin’s Metamorphoses and Carl Freedman’s Critical Theory and Science Fiction. Especially returning to this text after reading Suvin and others, I am struck by just how effective the constellation approach appears when compared to either the binary or constructionist approaches. Csicsery-Ronay’s definition will play a strong role in my approach to the large SF critical analysis project I announced two weeks ago.

Next Steps

Next I will be reading Locating Science Fiction by Andrew Milner, another work which purports to make sense of a complex genre in a way that a binary definition isn’t capable of, at least according to the book’s back matter. More on this in my next post!

January 5, 2019

A Historical Definition of SF

I’ve spent the last few days with two books by Adam Roberts. The first was the New Critical Idiom handbook Science Fiction, and the second The History of Science Fiction, part of Palgrave Macmillian’s “Histories of Literature” series.

Naturally, in order to proceed with a history of SF, one must first define it, and so Roberts begins each book with a chapter that lays out common definitions, as well as his own. His definition, unsurprisingly, is rooted in an understanding of the genre’s history.

The Origin Point

When did SF properly begin as a genre? Most fans today would probably agree with one of two common answers to that question. The answer most common in academic circles was articulated by Brian Aldiss, who considers Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to be the first SF novel. Thus, according to Aldiss, SF begins in 1818. However, another conception of the SF has the genre beginning in the twentieth century. That position is rooted in the fact that Hugo Gernsbeck coined the term “science fiction” in 1926.

Roberts poses an entirely different origin altogether: “SF [is] a specific and, as it happens, dominant, version of fantastic (rather than realist) literature; texts that adduce qualia that are not to be found in the real world in order to reflect certain effects back upon that world. The specificity of this fantasy is determined by the cultural and historical circumstances of the genre’s birth: the Protestant Reformation, and an attendant cultural dialectic between Protestant rationalist post-Copernican science on the one hand, and Catholic theology, magic, and mysticism on the other.” (The History of Science Fiction, 3)

According to Roberts, SF arrives at the moment when scientific rationality becomes powerful enough to come into conflict with older traditions, roughly the late sixteenth century. SF arose in response to the need to explore the changing ideological landscape of the world via literary art. His definition encompasses both science fiction and fantasy. The technologist and engineering-oriented strand of SF is a result of the Protestant ideological influence, and the fantastic strand a result of the Catholic influence.

Roberts goes on to outline a position that dismantles the terms “hard” and “soft” science fiction. The former refers to SF that purportedly adheres to scientific principles, while the latter refers to SF that adheres only loosely or not at all.

However, science proves no truths. As Karl Popper famously showed, science consists of a very large set of postulates, for which we do not yet have any contrary-indicating data. To give a concrete example, I can propose a theory, such as, “all trees have leaves.” As long as my experience is limited to certain biomes, I can hold this theory; it will remain “scientific.” But, the first time I or one of my colleagues encounters a conifer, my theory will fail and will no longer be accepted as science. (This principle of the body of scientific knowledge being in perpetual flux is the crux of China Miéville’s critique of Suvin’s “cognitive estrangement,” which I discussed in the previous post.)

In light of this, theory does not seem to support dividing SF into “hard” and “soft” variants, regardless of whatever the SF fandom may do. In Roberts’s opinion, this division is useful only in as much as it indicates two kinds of SF readership, one which accepts only “hard” SF as valid and ideologically aligns with Protestant rationalism, and another perfectly happy to engage with “soft” SF and ideologically aligns with Catholic mysticism (or, more often, some interesting intersection of the two).

One Old Definition and Two New Ones

In his review of extant definitions of SF, Roberts first cites Suvin, whose definition I’ve already discussed in two previous posts, that of SF as a literature of “cognitive estrangement” defined by the presence of one or more “nova” . Roberts goes on to cite two more definitions, those of Robert Scholes and Damien Broderick. Their respective works are Structural Fabulation and Reading by Starlight. At the time of this writing, I am still waiting for my copies of these books to arrive, and so I will have to limit myself to discussing what Roberts says about them.

Robert Scholes’s definition is the title of his book, “structural fabulation.” “Fabulation” equates essentially to a text which depicts a world disjunct from the real world, and “structural” to those fabulations being arranged in such a way as to cause the reader to reflect the fantastic world onto their lived experience. Essentially, this sounds like a reiteration of Suvin’s “cognitive estrangement” in different words, but Roberts insists that Scholes is departing from Suvin, in that his definition accepts fantasy, whereas Suvin’s opposes it. Notice that fantasy nova can still be “structured,” whereas Suvin insisted that fantasy nova were “non-cognitive” or even hostile to cognition.

Damien Broderick’s definition is much more complex, not to mention multivalent. I will dedicate a future post entirely to its exploration. Suffice it to say, Roberts seems to latch on to one of its components, that SF contains “foregrounding icons and interpretative schemata from a collectively constituted generic ‘mega-text’” (Broderick in Roberts, Science Fiction, 11). That’s an impressive bundle of words with a crucial concept for Roberts: the “mega-text.” This “mega-text” is, in other words, all works of SF that have come before. This definition (or at least, this chunk of Broderick’s definition) defines SF as the sum of all props (“icons”) and explored concepts (“interpretative schemata”) that have come before in SF literature. I can see the appeal for Roberts, given his interest with SF history and the large portion of SF literature prior to Shelley that’s been unfairly consigned to lesser status than more recent work, but this definition of Broderick’s is essentially post-modernist, and that introduces (for me) a big problem.

Post-ModernismRoberts opens Science Fiction with discussion of those writers who have tried to define SF in the form of a tautology, a thing defined as being its own definition. He gives a number of examples, and dismisses them. It is then curious to see him latch on to Broderick’s definition, since a post-modern definition such as his is, essentially, a much more complex tautology.

For example, if one individual says, “this book is SF, because I recognize it as SF,” this is a tautology that Roberts denies. However, if, as in Broderick’s definition, hundreds of people across multiple centuries construct stories, and an individual at some future point is able to show how all those works form a web of relationships with one another, and then that individual points at that web and says, “this is SF,” this, Roberts (via Broderick) seems to accept. I would argue that that is just another tautology, unless the critic were to apply some kind of normative principle to the creation of the relationships, but this intervention of the critic is a behavior that post-modernism discourages, because post-modernism aims to be descriptive rather than prescriptive.

Darko Suvin articulated a version of my sentiments well in the second edition preface to Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: “Thus, homo sapiens sapiens is … a norm-creating animal, there’s no way out of that. Nihilism is only useful insofar as it destroys norms and values which deserve that, … and quite useless insofar as it pretends there are no norms. … [A]t any particular moment in sociohistorical spacetime there exist for given purposes normative systems—however flexible and complex—which enable us to say that David Feintuch and Dean Koontz wrote bad SF whereas Piercy or Robinson write good SF. … [I]f Post-Modernism means no norms…, then I’m an impertinent modernist.” (xlvi-xlvii)

You can call me an impertinent modernist, too.

Next Steps

In my next post, I will be returning to the book that contained such an interesting description of Suvin’s concept of cognitive estrangement and the novum, that it got me hunting for and ultimately reading Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. That book is The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction by Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr. His definition of SF is interesting because it is multi-faceted, but it decidedly not post-modern, as in Broderick’s.

January 1, 2019

Genre Boundaries: SF and Fantasy

Today I continued my exploration of the backmatter of the second edition of Darko Suvin’s Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. The second essay of the backmatter is titled “Considering the Sense of ‘Fantasy’ or ‘Fantastic Fiction’: An Effusion.” This essay explores the relationship between science fiction and fantasy in detail.

Suvin dismissed Fantasy entirely in the main text of Metamorphoses. Recall from yesterday’s blog post that the crux of SF is “cognitive estrangement.” The “cognitive” portion involves the reader reflexively comparing the altered world of the SF novel to their real world and reaching a new understanding about humanity, society, etc. Suvin allows in Metamorphoses that Fantasy can produce estrangement, but owing to the fact that the worlds of Fantasy are completely and utterly disjunct from the real world, he concludes that Fantasy’s estrangement cannot be “cognitive” in the way that SF’s estrangement can.

His “Considering the Sense of ‘Fantasy’” essay (written more than two decades after Metamorphoses) partially reverses this claim. Suvin opens with the admission that both SF and Fantasy are capable of sufficiently “cognitive” estrangement, but maintains that for SF the job is easier due to Fantasy’s structural limitations (Metamorphoses, 388). In a telling section on “science fantasy,” Suvin adamantly denies that anything productive can come from blurring the genre boundaries, since doing so would corrupt any potential cognitive qualities that the SF elements of the text might be capable of (415-20).

China Miéville on Fantasy

I decided to follow up Suvin’s essay with China Miéville’s essay, “Cognition as Ideology,” in Red Planets, since I recalled from Gerry Canavan’s introduction to Metamorphoses that Miéville dissented from Suvin’s definition, and I trusted that Miéville would have something interesting to say on behalf of Fantasy. As I’ve come to expect with Miéville, I was not disappointed.

Miéville deconstructs Suvin’s concept of cognitive estrangement rather deftly in my opinion. Here’s a rough outline of his logic:

Science is an evolving field. The body of knowledge it generates gets revised as new discoveries are made. What is accepted science today, may be discovered to be unscientific tomorrow. Ergo, in order for a story’s elements to generate conformant “cognition,” they must constantly adapt to changing and evolving research. This is impossible for a story, since a story is an artifact fixed in a specific time, place, and culture of its creation. No work can be sufficiently “cognitive” by this definition.

Okay, let’s adjust the definition, then. Miéville introduces Carl Freedman, author of Critical Theory and Science Fiction, who wrote that what is important is not “cognition” per se, but rather a “cognition effect.” The difference is subtle. “Cognition” involves a story being consistent with the science and technology of the real world. A “cognition effect” involves a story being internally consistent with the mechanics of any science and technology it represents within itself.

But, wait a minute. If a “cognition effect” doesn’t depend on any connection to the reader’s reality, then neither is it dependent on the reader’s logic and reason. Rather, as with fiction of all kinds, it requires readers to suspend disbelief and enter this world of the narrative. This leaves the door open not just for legitimate cognitive engagement, but also for flimflam and more insidious influences.

At this juncture, “cognitive estrangement” has fully broken down. A text cannot contain it, because any text that is internally consistent meets the definition, even if it maintains no connection or relationship to real-world logic and formal reasoning; ergo, no cognition of any kind. (Red Planets, 239)

Miéville proposes instead to understand SF and Fantasy both as genres of alterity (244). Miéville agrees with Suvin that a good SF text allows the reader to reformulate their conception of reality by offering a vision of a radically different world, but Miéville disagrees that Fantasy is any less up to the task, and further, both genres accomplish that goal through depictions of alterity.

My ThoughtsIt seems to me that most readers’ consideration of genre happens at the time of book selection, as opposed to theorists, who are concerned with genres for much longer after the fact. Whereas the theorist’s job is to organize works into systematically comprehensible and analyzable corrals, readers tend to use genres to find work that they will engage with best.

I can think of three different kinds of reader approaches to SF and Fantasy genres. Group 1 searches out books that contain the kinds of props they enjoy (aliens, spaceships, and black holes; or, knights, wizards, and goblins). Group 2 is invested in stories of particular plot-type or espousing a particular worldview (engineering and math being utilized complex problems and improving the world; or, heroic adventure, and the struggle for good to overcome evil). Group 3 expects stories to contain cognitive spaces for intellectual exploration (questions of where we are going as a society, how we are changing, and how we should direct change). The generic division into “SF” and “Fantasy” will be highly practical for groups 1 and 2; it will be confounding, and probably more than a bit irritating, for group 3, especially if the individual in question is also a literary theorist.

I suspect that both Suvin and Miéville fall into group 3. Suvin solved the conceptual problem by denying that groups 1 or 2 were worth his theory paying any attention to (it’s worth noting that SF represented a much larger body of work than Fantasy in 1979). Miéville appears to wish to solve the problem by collapsing the distinctions completely, if not now, then hopefully in the near future (he suggests as much on p. 244).

I can see how the generic categories are useful to groups 1 and 2, even though I find myself in group 3 as well—either genre will do as long as the story is sufficiently intellectually engaging, and I personally would happily clump the genres together if I had only myself to worry about. I think that Miéville is on to something with “alterity” being the shared component that unites SF and Fantasy, but I wouldn’t wish to obliterate the distinction between SF and Fantasy, because I can see how it is useful to others. Like Miéville, I am opposed to Suvin privileging SF over Fantasy.

Further Reading

J.R.R. Tolkien wrote essays, and one of them is about Fantasy! The book is called The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays. I can’t wait for this one. Thank you, Darko Suvin!

Suvin also cited an article by Umberto Eco called “Towards a New Middle Ages.” It’s in a collection of essays called On Signs. Astonishingly, it was written in the 1970’s.

December 31, 2018

Revisiting Darko Suvin

The Metamorphoses of Darko Suvin

My interest in the literary theory surrounding science fiction (SF) goes back years. When I first started exploring it so many years ago, it became overwhelmingly apparent after only a cursory survey that one writer had powerfully influenced all subsequent work in the field. His name is Darko Suvin, and he is best known for a book first published in 1979, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction.

At the heart of Metamorphoses is the question of what SF is. The answer to this question may seem obvious at first blush. One is tempted to think, “If I walk into a bookstore, I go to the science fiction section, and that’s where I know the science fiction is. Everything there will be science fiction, and everything else will be something other than science fiction, right?” You might be able to do just that, but remember that books are shelved at bookstores and libraries according to the genre designation assigned by their publishers. Is SF, then, whatever the publishing companies of the world decide it to be? Or, is there some measure one can apply to determine whether or not a story is SF, even in isolation of any publishing company, bookstore, literature department, or other institution? Is there a definition of SF that doesn’t ultimately come down to an arbitrary choice made by a person who wants a work to have a particular label attached to it?

In 1979, Darko Suvin was the first to attempt such a definition, and the definition he outlined in Metamorphoses has shaped the discussion of what SF is in literary scholarship ever since. The crux of his definition is the phrase “cognitive estrangement.” In essence, Suvin argues that an SF text must pose world configurations or human relationships substantially altered from those of the ones we see around us in our everyday lives. These could be new technologies, aliens, mutations, altered social dynamics, a different history—any difference that causes the reader to feel that the story “estranges” them from their everyday reality. However, mere estrangement is not enough. The differences in the world of the story should not be random or merely interesting, but rather, they should cause the reader to see something about their real world that they weren’t aware of before. That is the “cognition” part, and Suvin is adamant that the two elements, both cognition and estrangement, must interact in order for a work to be considered SF. Some researchers found this to be problematic, but that’s a big discussion, so I’ll save that exploration for a later post.

The manifestation of cognitive estrangement within an SF story, for example, the androgens of Ursula K Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, or the flooded, tropical London of J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World, Suvin called a story’s “novum.” SF stories can have many nova (China Miéville’s novels provide a panoply of examples), but for Suvin a good SF story only needs one.

Implications for My SF Critical ReviewYesterday, I announced that I will be writing a critical review of the science fiction genre. The review will have two major parts. The first will be a trio of essays about science fiction. The second, much longer part, will be biographies of the twelve authors I consider most important to SF over the last two centuries, and reviews of their major works.

The first of the three essays is titled “What is Science Fiction?” My goal for the essay is to review Suvin’s work, the work of his supporters and his critics, and then to formulate my own position. At the time of this writing, I find cognitive estrangement to be an enormously useful tool for analyzing SF stories’ merits and demerits. However, I am open to alternative definitional schemata, should they prove superior.

The Second Edition and MetaphorWhen I first tried to get my hands on a copy of Metamorphoses of Science Fiction, it was out of print. I did manage to snag a first edition, which I still have today. Fortunately, Peter Lang Publishing has put out a Second Edition with additional material a few years ago, and so the work is now much more readily available.

Today, I re-read the introduction by Gerry Canavan and Darko Suvin’s second edition introduction. I initially read these a few years back when the second edition was first released. The second edition also contains additional essays by Darko Suvin, which I had never gotten around to reading. I read the first of those, “Science Fiction, Metaphor, Parable, and Chronotope,” in which Suvin draws connections between metaphor analysis and his conception of the novum. Both, he argues, are vehicles for cognitive estrangement. Even more interesting was the section describing how good stories (and not just SFF stories!) can be interpreted as sequences of interlocking metaphors.

There are two more essays in the back of the second edition, which I’ll be reading tomorrow.

Further ReadingAs always happens when reading scholarly works, the bibliographies and footnotes provide a number of vectors for further study. Here’s a summary of where I’ll be heading after I’ve finished Metamorphoses.

Positions and Presuppositions in Science Fiction, by Darko Suvin. Canavan cited this work by Suvin as containing a formulation of Suvin’s reponse to critics of his theory of cognitive estrangement. Seems like a good place to start hunting for references to dissenting voices.

Red Planets, edited by Mark Bould and China Miéville. Canavan also quoted an essay at the back of this book by Miéville called “Cognition as Ideology: Dialectic as SF Theory.” It seems Miéville recommends a reformulation of cognitive estrangement along somewhat different lines. Clearly worth a look.

Scraps of the Untainted Sky, by Tom Moylan. Canavan cited chapter two of this book, published in 2000, as containing an analysis of Metamorphoses in the context of the time it was written.

Speculations on Speculation, edited by James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria. Canavan cited an article from this collection in order to make a point about terminology (the shift from “science fiction” to “SF”). That particular topic isn’t terribly relevant to the thesis of the essay I’m developing for my book, but Speculations could turn out to contain other useful insights.

And last but not least, I ran into citations of two articles from Science Fiction Studies that are worth following up. The first is “Surveying the Battlefield” by Ursula K Le Guin. The second is “The Absent Paradigm” by Marc Angenot. Both are available freely online.

December 30, 2018

New Year; New Project

About eighteen months ago, I embarked on a completely new kind of literary adventure. I scrapped my long science fiction reading list and began reading Classics, starting with Plato and Aristotle. I’ve been away for a while, and I even announced earlier this summer that I would be giving up this site and the domain, but when the due date came, my gut told me to keep it going.

I now feel I have gained adequate perspective to return to SF on my own terms, and with a new purpose. I want to write a survey of the genre.

This survey will be divided into two parts. The first, much shorter part, will be a series of essays about topics concerning SF. The second, much larger part, will be biographies, reviews, and literary analyses of the twelve authors I consider most important to the last two centuries of science fiction.

I plan on debuting the rudiments of all this work on this blog for free. Each of the essays and reviews will appear here first, in somewhat abridged form. The final, more substantive works will appear in ebook and print form, as I finish each section.

Here is the working outline (subject to revision):

TopicsWhat is Science Fiction?

Solidity in Science Fiction and the Intellectual Divide

A Trajectory for the Future

Biographies & ReviewsMary Shelley

Jules Verne

H.G. Wells

Aldous Huxley

Yevgeny Zamyatin

Boris & Arkady Strugatsky

Staisław Lem

J.G. Ballard

Ursula K Le Guin

Kazuo Ishiguro

David Mitchell

China Miéville

This is a big, multi-year project. I will consider 2019 a success if I can get through Mary Shelley. The three topics above may appear simple in outline form, but there’s a lot of research for me to do. Fun research. Exciting research! On my own terms, too. This is going to be great.

Hey, SF. I’m back.

September 9, 2018

The Many Conflations of Jeff Goins

Introduction

About a month ago, Real Artists Don't Starve popped up on my Goodreads feed, and, based on the title, I decided to check it out. My history with the practice of an art (in my case, prose) is extensive, and although my history with the business of publishing is sordid, I also learned a ton. I was curious to see if Jeff Goins had written something that would rise above the general dredge of self-help literature and teach me something I didn't already know about managing the business aspects of art.

Sadly, it was worse than that. Not only did Goins fail to teach me anything new, his approach to discussing the topic introduces further confusion with a number of inappropriate conflations. By this I mean that Goins's frames of reference for argumentation only fit reality if you focus on a very narrow band of human experiences.

My intent in this review is to pull apart these conflations and fit their targets into frames of reference that fit broader swaths of reality. I will show that the sentiment behind the title, that "real artists don't starve," while, in a sense, true, is not true for the reasons Goins claims. On the contrary, the current state of the world is about as far from a "New Renaissance" as it could possibly be.

Artwork versus ProductI will start with the conflation that makes most of the book's premise possible—namely, the conflation of a piece of artwork with an artifact of commercial production. It is through this lens that we can see Goins at his most self-contradictory. Money both "matters" and "does not matter" (chapter 12), and immediately following chapter 9, "don't work for free" (e.g. sell your work), comes chapter 10, which encourages the artists to "own your work" (e.g. don't sell your work).

The fundamental tension here is ultimately the question, "who does the generative activity serve?" Goins appears to want to live in a world where the products of artistic endeavor can be made profitable solely by making the right social connections. However, this stance ignores the fundamental reality that works of art, in the true sense of the word, will be inherently unattractive to the vast majority of people, and therefore fail as a product.

Artwork and products are fundamentally different things. Works of art are crafted for no goal other than an artist's realization of their vision. Products are crafted to sell. Real artists decide to create the former, and only later concern themselves with the latter, if at all (because the artist should be devoting as much energy as possible to honing their art). To pretend that there is some world where works of art can also be successful products is either to debase art or to presume a wildly unrealistic analysis of the kinds of things that are capable of selling well.

If one adopts the more realistic outlook I have outlined here, the result is a fundamental tension between spending one's time on making enough money to live comfortably and spending one's time practicing one's art.

Buying Time versus Selling OutGoins treats the subject of selling out haphazardly. He gives no concrete examples of what it consists of, but it seems to be something akin to spending all of one's time practicing one's art in a context in which the terms of that art are dictated by someone else. This is odd, because all of the paths Goins defines as leading to the "Thriving Artist" (a counter archetype to the "Starving Artist") consist of being a slave to market forces of one sort or another.

Goins outlines the three forms of supposed independence in chapter 12: create "art" that the market approves of, get a patron, or teach people how to create "art" that the market approves of (and charge for the service). To my mind, the first and third of these options entail enslavement to the market, and the second entails enslavement to a patron.

Interestingly absent is the concept of buying time, by which I mean the act of saving up money for the purpose of freeing oneself from any of the above constraints. Money is power, and, as such, is the only way in our modern society of achieving freedom from market forces. Having conflated artwork and product, the concept of "selling out" has become non-sensical, and the real path to freedom (generating a savings) has been lost in the ensuing quagmire.

Patronage versus EmploymentGoins's treatment of patronage is also problematic. Michelangelo features prominently throughout the book, and it is here that the topic of patronage is first broached. However, when the discussion moves on to modern forms of patronage, another conflation appears.

Patrons, in Goins's model, can be a business that wants to invest in one's art, or crowdfunding channels like Kickstarter and Patreon. I would argue that neither of these is truly "patronage." A better term would be "employment."

In the case of a business, this is quite clear. A business will be forced to shutter if it does not submit to the pressure of market forces, and those forces will inevitably translate to pressure on their hired artists. Furthermore, Kickstarter and Patreon "patrons" are actually nothing more than the pure manifestation of market forces with the middlemen (managers and executives) removed.

What Goins glosses over is the fact that real artists like Michelangelo had difficult relationships with their patrons, since they realized that their ability to execute on their vision would ultimately be constrained by the relationship. We know that Michelangelo's relationships with his patrons were difficult at best. "[A]lthough I have served popes, ... this I did under compulsion," he writes.¹ For his last major work, the cupola of St. Peter's, Michelangelo refused payment, worrying that he would sunder his art by tainting its creation with the profit motive.

Executing on a Vision versus Pandering to the MassesGoins displays a complete lack of understanding of this difference, and if he weren't writing a book about the logistics of creating art, then I might give him slack. Our culture at large seems to have lost this distinction entirely. I've written before about how it seems that our only remaining measure for "good" seems to be "market value."

If artwork and products are the same thing, and if patrons and employers equate, then the idea of executing on a unique vision evaporates. Goins even goes as far as propping up the idea that artists should "steal" from one another (chapter 2). Interestingly, he uses the more correct term of "influence" many times, but his frame describes a method for making products more appealing by clearly appropriating the tropes and genre conventions of prior works ("stealing"). The title of chapter 2 is, "Stop Trying to Be Original."

A better frame for the conversation would be to start with the fact that originality is a hard sell, but trying to achieve it is the only way to execute on a vision that is true to oneself. Market motivations have little place in a discussion of art.

Artist versus Creator versus BusinessmanI have saved my least favorite conflation for last, and that is the total merger of artists, creators, and businessmen into a single category. Goins considers all of these to be "artists."

The conflation is most evident in the example biographies he provides. Michelangelo, Van Gogh, and F. Scott Fitzgerald are discussed vis-a-vis Elvis Presley, Jay-Z, Beyoncé, an astronaut who paints, and a major league baseball player you will never have heard of who is working on a movie. Most disturbingly of all, the following also fit easily into this same category: Gordon Mackenzie, Jeff Bezos, and Steve Jobs. All are, apparently, "artists."

Let me make this utterly clear. Artists (Michelangelo, Van Gogh, and Fitzgerald) fight tooth and nail in a rough world to execute on their artistic vision as faithfully as they possibly can. Creators produce what might be generously called mass-cultural artifacts, because they either pander to the market, or more likely, lack a vision entirely, but still enjoy the act of creation for its own sake (Presley, Beyoncé, et al.). And, completely outside the realm of any of this are businessmen, who neither have artistic vision nor produce artifacts, but simply manage large organizations of people (Mackenzie, Bezos, and Jobs).

The ability to manage groups of people is certainly a skill, and it is certainly important, but it is far too much of a stretch to call such work "artistic." Further, our society would benefit from a renewal of the distinction between art and products, and consequently artists and creators. The reason that many people can get excited by the artifacts generated by creators is because they are designed to be appealing. And for many, this feeling of appeal equates to goodness.

But that feeling is shallow. I fear that too many consumers have never reached, albeit counter-intuitively, for something difficult, something old, something strange, something complex—simply for the joy of doing the work to understand someone else's vision. That is the truly lost art.

ConclusionMost real artists probably don't, in fact, starve. But what they do realize is that, optimally, they would hone and practice their art independently of market forces. This invariably means compartmentalizing one's life to separate practicing one's art from the business of thriving in the world. This was my big lesson from publishing, and it was disappointing to see Goins send people off to run the same fool's errand I ran for three years.

What real artists do is execute on a vision that is wholly theirs, one which may have a number of influences, but which is truly original. Too bad that sentence can't be turned into a catchy title. But even if it could, I doubt that such a self-help book would sell.

Bibliography¹ The Story of Art, E. H. Gombrich, Phaidon Press, 1995

May 28, 2018

Leveling Up

I've been quiet this past year, but I've been busy. Right around the time I finished up the prior post on this blog, the one about the publication of the second edition of Insomnium, I also finished reading a book called The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom. Reading this book helped me to pull together a number of intellectual threads I'd been exploring for the prior three years.

It is too early for me to go into much detail on the topic of where my intellectual explorations have led me. Such elaboration will have to wait for a later date.

What I can say is this. In August 2017, I scrapped my science fiction reading list and began reading the Classics, starting with Plato's dialogues. I kept two science fiction books on my list, Second Foundation by Isaac Asimov and MaddAddam by Margaret Atwood. This was solely because I had already read the first two books in their respective trilogies, and I wanted to close those stories off. I finished reading both of those books last year. At the time of this writing, I am in the middle of The Histories by Herodotus and The Laws by Plato.

A closely related parallel in my life is the subject of finances. I realize now that when I started Fuzzy Hedgehog Press, it was much, much too early for me to be starting a small business. A business requires a prolonged investment period before it will break even, let alone generate a profit. I learned a ton from the experience, most importantly that I love book interior layout and cover design, but I must get my financial house in order before I can properly approach these disciplines.

A year and a half ago, I shut down Fuzzy Hedgehog Press. At the time, shocked by the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency, I simply wanted to rid myself of my onerous student loan debt as quickly as possible, and so I nixed my most my onerous expense—the press. I wasn't at all considering what might come after that debt was gone. Now, I find myself within striking distance of being debt free, and I am giving a lot of thought to just how I am going to go about achieving my goals once that day arrives.

I now have a plan. Part of that plan involves shutting down this blog when my renewal comes up this October. The purpose of this is to free up those funds so that I can invest in the future I want to create.

Goodbye for now. I promise, however, I will return stronger and better than I am as I depart.