Mariella Hunt's Blog

August 27, 2025

James Madison, Father of the Constitution

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

SubscribeAugust 19, 2025

How the Post Office Created America

I have long been a fan of ‘snail mail,’ the practice of writing letters on paper. Using envelopes and stamps, we send tangible evidence of affection to family and friends. However, our mailboxes do not provide the same sort of thrill as in olden days; many approach it every day with a chagrin.

It seems that, lately, we receive junk mail and advertisements more often than letters. We traded all of that for the speed and convenience of instant messaging and e-mail.

From the beginning, there was more to the post office than bills and catalogues. It was important to the growth of America.

In her fantastic book, How the Post Office Created America, Winifred Gallagher tells the story of our Post Office. This story is far more exciting than I expected. Today, a walk to the mailbox can be a waste of time (and a disappointment, when bills arrive).

You might see your mailbox in a new light, once you learn how the Post Office kept us together as a nation. Before the explosion of catalogues and coupons, colonists and revolutionaries depended on the post.

If America was a body, the post offices were her veins. Mail sent life to little towns as they were established. The post office kept this newly independent body running, united, and healthy.

Benjamin Franklin, Postmaster GeneralA post office did exist before the American Revolution. It belonged to the British government, and one of its purposes was to keep the colonies in check. (It’s no coincidence that the Stamp Act was one of the ‘last straws’—sparking rebellion in colonists who were already disgruntled).

Benjamin Franklin seemed to have been involved in many things, but I wasn’t aware of his contributions to the post. He was certainly a celebrated scientist and scholar. I learned from Gallagher’s book that he had also been America’s Postmaster General.

Appointed in 1753, Franklin served as overseer for all existing post offices in the colonies. He was given the ability to appoint new postmasters in small towns.

Franklin, ever the innovator, had ideas for streamlining the process, ensuring that letters reached their destinations faster.

I quote from Gallagher’s book:

At a time when overland travel was a grueling ordeal, he personally surveyed and strengthened the sketchy system that connected, albeit erratically, the widely scattered, culturally diverse provinces from Falmouth, Maine, to Charleston, South Carolina. He made many improvements, from plotting more efficient routes marked with milestones to speeding up delivery; round-trip service between Boston and Philadelphia was cut from six weeks to three, and one-way service between Philadelphia and New York City to a mere thirty-three hours.

The post office was not only important for delivering letters. Vital newspapers traveled by post, as well. Newspapers helped people in remote places keep up with what was going on in their shifting world.

Benjamin Franklin was also the editor of his own newspaper. During the French and Indian War, Franklin used the post and his newspaper to begin rallying troops:

Just a month before the Albany Congress, Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette had debuted America’s first political cartoon. The simple drawing showed a snake that had been cut up into pieces, signifying the colonies, and the caption read JOIN, OR DIE. The immediate reference reflected Franklin’s concern over the need for the English provinces to unite against the French in the looming colonial wars. On a subtler level, however, the sketch invited a provocative question: Why stop there? Within a generation, Franklin and the post would be at the center of a revolution.

Franklin’s 1754 political cartoon for the Pennsylvania GazetteBenjamin Franklin’s Print Shop

Franklin’s 1754 political cartoon for the Pennsylvania GazetteBenjamin Franklin’s Print ShopThe first chapter of Gallagher’s book tells us about Benjamin Franklin’s early years. This includes his work as the owner of a print shop. Such facts are crucial for understanding important figures, but they’re not often taught in history class.

I enjoyed reading about these details, because they added color to his image in my mind. They explained how he was largely a self-made man. He did have various patrons, but worked hard all the same.

Benjamin Franklin aimed high, and this reflected in his work as Postmaster General. He was not content to settle for a flawed post system.

I’d love to offer some context about his print shop, as well. Such was its success that the British government offered him a promotion:

Franklin went on to open his own print shop on Philadelphia’s bustling Market Street and prosper. … In 1737, Britain recognized the enterprising printer’s merits by appointing him Philadelphia’s postmaster, and in 1753, he was promoted to the important position of joint postmaster general for all the North American colonies.

A map of early U.S. Post Routes

A map of early U.S. Post RoutesBenjamin Franklin worked hard to improve the Post Office system. However, this service had not yet finished evolving.

Since the country was growing at a fast pace, its Post Office was in constant need of fine-tuning. As settlers began to move west, postmasters faced new challenges. They needed a postal service that would connect settlers with communities they were leaving behind.

This meant new Post Offices and improved roads to get to them. The country was growing; new veins were needed in order to keep her alive.

The Value of FarmersIt was important for farmers to make their homes in distant places. The country depended on their work. It was in the government’s best interest to make them as comfortable as possible. The least that could be done was ensure that their mail would arrive.

This would not be a simple matter. After the war, it was difficult to coax all thirteen states to agree on a road system. They might have fought for independence together, but a sense remained that they were thirteen different bodies. Not all of them had the same priorities.

If roads could not be built to make the process easier, was it possible to improve the system?

Eventually, after several debates among various states, a few postal roads were established. These roads soon became gathering points. Settlers built their homes as near as possible to Post Offices.

The Post Office became a much-needed social spot. Men and women went to gather their mail, enjoying chats with neighbors in the process. This was especially common in places where the post office happened to be inside stores, such as farmers’ markets.

Early post office with post boxes.

Early post office with post boxes.If only it could be like that now! We could look forward to checking local shops for our mail. Even if we didn’t have any mail, it would offer opportunities to talk—not text—with friends.

We would look forward to getting the mail again.

Inventing Home DeliveryAs the Post Office grew, more changes arrived.

During the Civil War, it was suggested that the Post Office should deliver news from battlefields to family members. We can understand the reasoning behind this. Countless men died during that war, due to injury and illness. Imagine the constant scenes of heartbreak if, each time a wife or mother visited the Post Office, she were to discover that the man she was waiting for had died.

The Postmaster General of that time insisted that such moments be private. Initially, there was debate about the propriety of having a mailman approach a house where a woman might be alone.

However, the proposal was approved. These families had lost so much; they at least deserved privacy in which to grieve.

Delivering letters was another challenge. This service was new; mailboxes were not yet common. Therefore, the post had to be hand-delivered. If no one was home the first time to receive their letter, the postman held onto it, finished his rounds, and tried again.

Eventually, the envelope was received. If the news was bad, we can imagine that the recipient wished it had never arrived.

Though our Post Office has had many improvements, the process of delivering mail from all over the world continues to present complications. These include transportation, organization, and hiring workers.

Since the Post Office is a service that benefits all of us, many postmasters have tried to find solutions. How the Post Office Created America offers, in its final chapter, a compelling summary of what could be improved.

I read this book on a whim. I never gave much thought to the importance of mailboxes. It is now clear to me that they served as lifelines, holding together a brand-new nation as it grew and explored unfamiliar land. It connected families, fending off a crushing sense of total isolation.

How the Post Office Created America was a fascinating read. If you want to know more about our early history and would like a new perspective, I recommend this book. It is not incredibly long, and it’s an engaging read.

What to Read Next:

A Brief Course on Revolutionary Painters

Though the American Revolution is recent history when compared to other events, much of it remains a mystery. With no photos to provide clarity, we rely on our imaginations for a good deal of it.

August 12, 2025

5 Reasons to (Finally) Read 1776

All book lovers know the happy dilemma of having too many books.

Many of us are blessed with shelves and shelves of volumes that we intend to read one day. There are so many—it could be a long time!—but no, we are not donating them. How dare you suggest such a thing?

We’re not donating them, but we haven’t read them yet, either. The reason is simple: We have several other books to choose from. (For the record, few book lovers understand the order in which they choose their own reads. It has little to do with the order in which the books were purchased.)

It has been said that a book is a friend—and that the friend is aware. A book will always tell you when the time has come to enjoy it.

(The quotes in this post are all from 1776.)

Owned, but not read…This year, I was beckoned by the book 1776 by David McCullough. I remember purchasing it long ago, soon after it was published. I purchased it in the spirit of “Everyone is buying it. Therefore, it must also be on my shelf.”

The risk with this mindset, is that such books can end up on the “Owned but Not Read” shelf.

This year was my time to read 1776. It didn’t take as long to get through as I thought, and I knew halfway through that it didn’t deserve to be in the “Owned but Not Read” shelf.

It is an important story, especially now that we are nearing the 250th anniversary of our country. Now that I have, at last, finished this book, I understand why it’s been so popular (for those who’ve actually read it).

It isn’t only important for Americans. The story is so surreal that I’m sure everybody would enjoy it.

If you need five reasons to read 1776, here are my suggestions. (I’m aware that six reasons would make more sense, but for the sake of post length, we’ll limit it.)

If you are on the fence, maybe a couple of these points will compel you to reach for the book!

1- It tells about ordinary soldiers.This year, during my journey exploring early American history, I’ve been reading a lot of biographies about the Founding Fathers.

These were obviously not ordinary men, with many born into some form of privilege. They tended to be wealthy in land and well-educated. Even gentleman-farmers did not get sweaty. Jefferson owned farms, but slaves took care of the hard work.

1776 does mention these men. How could we tell this story without them? However, they do not overshadow the ordinary soldiers. This book honors the common men who fought and died for that cause, which I appreciated.

McCullough helps us to see that war from the viewpoints of working husbands and fathers. There is a special greatness about those who signed up to fight, knowing that they were imperfect and unprepared—and might lose their lives.

McCullough makes a point of “showing” us how precarious the matter was for these men and their families. In the following passage, he recounts how British commanders Burgoyne and Percy dismissed them as ‘peasantry,’ ‘ragamuffins,’ and ‘rabble in arms’:

2- It introduces us to King George III.That so many were filthy dirty was perfectly understandable, as so many, when not drilling, spent their days digging trenches, hauling rock, and throwing up great mounds of earth for defense. […] It was dirty, hard labor, and there was little chance or the means ever to bathe or enjoy such luxury as a change of clothes.

In many books about this war, King George III is mentioned in passing. It’s not hard to imagine why; after all, he didn’t do the fighting.

1776 was the first book I’ve found in which the author troubled himself to introduce the human who was king.

King George III of England (1771), Johan Zoffany

King George III of England (1771), Johan ZoffanyKing George III was more than an ominous figure feasting in the background. The following paragraph helps us to “see” him:

George III had a genuine love of music and played both the violin and piano. (His favorite composer was Handel, but he adored also the music of Bach and in 1764 had taken tremendous delight in hearing the boy Mozart perform on the organ.) He loved architecture and did quite beautiful architectural drawings of his own. […] He avidly collected books, to the point where he had assembled one of the finest libraries in the world.

It’s important to know about the king. Knowledge of King George III provides contrast, which in turn helps us understand George Washington.

Much has been made of the fact that the two rivals were called George. Many think it fate that the George who won did not have natural children; therefore, no American royal line followed.

This balance makes the story more poignant and exciting.

3- It mentions an imperfect Washington.George Washington is famous for having been able to maintain calm in impossible situations.

We remember him as being forever in control. I believe this does him a disservice—he was also human. There were times when he lost his patience; how could he not?

George Washington had been placed in charge of young, untrained, undisciplined soldiers. He needed to mold them into an army that could defeat an empire. Given those circumstances, there were surely instances when he felt fear.

During the battle at Kips Bay, he rounded on his soldiers, overcome with anger:

It was everything he had feared and worse, his army in pellmell panic, Americans turned cowards before the enemy.

In a fury, he plunged his horse in among them, trying to stop them.

Cursing violently, he lost control of himself. By some accounts, he brandished a cocked pistol. In other accounts, he drew his sword, threatening to run men through. “Take the walls!” he shouted. “Take the corn field!” When no one obeyed, he threw his hat on the ground, exclaiming in disgust, “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?”

There were also times in which Washington was a source of courage. He knew that, in spite of the odds, these men hadenlisted. They were imperfect, yet chose to risk their lives.

Washington’s March through the Jerseys (1908), J. L. G. Ferris

Washington’s March through the Jerseys (1908), J. L. G. FerrisDuring another battle, his presence stirred a different spirit:

4- It’s truthful about human fear.

The sight of Washington set an example of courage such as he had never seen, wrote one young officer afterward. “I shall never forget what I felt … when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him. Believe me, I thought not of myself.

“Parade with us, my brave fellows,” Washington is said to have called out to them. “There is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly!”

It’s said that hope is the last thing to die. We would like to believe that the rebels were always ready to fight. When provided with context, we can understand why this was not so.

Rebel towns were under siege from an experienced army of men, professed soldiers. They were prepared tactically; they had the motivation of decent pay. When Hessian soldiers arrived to assist the British, even the British shook their heads at Hessian savagery.

American men continued to die or become grievously wounded. Towns were raided, women and children brutally attacked. As victory seemed less and less likely, people grew desperate. They wished to ensure the safety of their families.

This safety seemed to arrive at last, when Admiral Lord Howe presented a proclamation on behalf of the King. It offered “free and general pardon” to all who, within sixty days, would take an oath of allegiance and “peaceful obedience.”

Those who took such an oath would:

reap the benefit of his Majesty’s paternal goodness, in the preservation of their property, the restoration of their commerce, and the security of their most valuable rights, under the just and most moderate authority of the crown and Parliament of Britain.

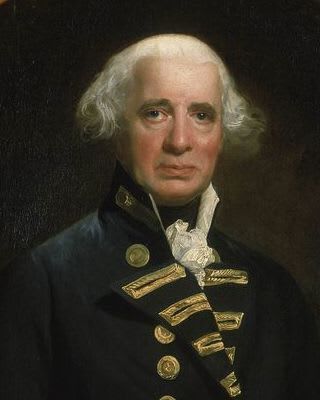

Admiral Lord Howe (1794), John Singleton Copley

Admiral Lord Howe (1794), John Singleton CopleyIn New Jersey, thousands eventually flocked to take the oath. It seemed the prudent choice, a way to ensure safety.

Astonishingly, Washington’s army held out. In spite of the flickering nature of their hope, the Treaty of Paris was eventually signed, ending the war.

5- 1776 was just the start.The war did not end until 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. During those years of tumult, the rebels suffered losses and gains. There is so much to write about during the years in between.

I’ve written about Benjamin Franklin, whose influence in France offered us great advantages. I’ve read about the frustrations of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, as they tried to forge alliances with other nations.

1776 wasn’t the only notable year of the Revolutionary War. It was the time when ordinary men—farmers and shopkeepers by profession—decided to risk it all. They went forth to fight an enemy that was much bigger than them.

McCullough’s book, 1776, tells their stories with sparkling prose. It offers vivid pictures of men and women who realized that better lives were possible.

If you are on the fence about reading it, I hope that this review can sway you.

David McCullough was an excellent author. Though this was one of his shorter books, it tells an important story.

Nearly 250 years later, the spirit of 1776 is alive. With our country’s anniversary drawing near, these pages offer an opportunity to go back in time. It’s an opportunity to celebrate, learning about 1776—how it started, and why it is worth fighting for to this day.

Have you read this book? If so, what do you think about my points? Feel free to comment and start a conversation!

August 5, 2025

Mary Todd Lincoln Wasn’t ‘Crazy’

This week, I discovered an article on a website called President Lincoln’s Cottage. It mentions a piece published in The Washington Post which bears the title, “Mary Lincoln wasn’t ‘crazy.’ She was a bereaved mother.”

I agree with the title—and am grieved that such an article is necessary. It was written by Callie Hawkins, who had been working at Abraham Lincoln’s Cottage for ten years when, tragically, her baby was stillborn.

It was not enough that she was grieving her lost child. Familiar with Mary Lincoln’s story, she was afraid that she would be perceived by others as ‘crazy’ because of the time that she spent grieving.

Mary Lincoln’s grief began in childhood, when she lost her mother, but it was after she began to lose her children that her brokenness became more visible—and more aggressively criticized. She even contacted spiritualists. Already a reckless shopper, she decided to purchase more things.

The Washington Post article comments of her husband:

President Lincoln felt these losses deeply, too, but he expressed it in more socially acceptable ways, like throwing himself into work, locking himself in his office or secretly visiting the crypt that temporarily held his son’s coffin at night. In a sexist society, his grief was viewed as a more heroic “melancholy” than Mary’s, who was dismissed as self-absorbed or insane — a stereotype that persists to this day.

More socially acceptable ways. In the three books that I’ve read so far about the Lincolns, it is Abraham whose melancholy is perceived as normal and even heroic. Only in the book Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly by Jennifer Fleischner is Mary Lincoln given a gentler portrayal: that of a broken soul born into the wrong time.

Click here to read the Washington Post’s article.

Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary

Mary, Mary, Quite ContraryIt’s said that history is written by the victors. While I don’t wish to believe that all historical outcomes we know of were composed in this spirit, one thing is for certain.

In 2025, we enjoy great advantages when it comes to learning. Not only are books more readily accessible for scholars (or simply people who wish to learn). If used with caution, seeking credible sources and cross-referencing, the Internet can provide us with many answers. We hold the world in the palm of our hands; we need only learn how to use it.

With such great power readily accessible, it’s no wonder that so many of us have committed our free time to digging truth out of texts written by ‘victors.’ By means of patient study, reading, and preparing to be wrong, we search for the truth. This includes seeking the truth about people who’ve been painted unfairly, based on the standards of their time.

Mind, I’m not saying that Mary was necessarily the gentlest of hostesses. I can’t claim, either, that everything negative written about her is wrong. At the end, I have neither the sources nor the talent to clear someone’s name and set history as we know it to rights.

I do have an opportunity to share my own thoughts. I’m not alone in perceiving an imbalance in the lore of our great President, Abraham Lincoln.

It’s true: there’s much about the Lincoln family that I don’t know. I’ve been to the museum near Ford’s Theater; I’ve seen that tower of books about his life. It’s not possible that I can read them all, but the first one I reached for this year disappointed me.

A Bone to Pick with CarnegieIt started with a friend’s copy of Lincoln: The Unknown by Dale Carnegie. He is a famous author who has become a staple in the literary canon. From his book, I hoped to learn things about the President, or be inspired to write an article. The book succeeded in that goal, but my research was driven by disappointment in how Carnegie wrote about Mary Lincoln, the President’s wife.

Lincoln: The Unknown seems, at first glance, to be a sensible narrative. Its length is not too overwhelming for younger readers. Style-wise, it is excellent, capturing Lincoln and portraying him as a hero. I felt that this was achieved at the expense of the woman to whom he was married.

By the time I finished that book, I could not say that I enjoyed it. I would never recommend it to someone who is just learning about that great President. Carnegie was determined to make Mary look as bad as he could.

It’s not possible that she could be perfect—no human being ever is. Neither is any human naturally the villain from every angle.

Lincoln: The Unknown consistently paints Mary in a negative light. First, she is the stalkerish, spurned lover. She’s a selfish woman who coerced a man into a miserable marriage. Immediately after this, she’s still selfish—but now she is a nagging wife, who goes out of her way to embarrass her high-profile spouse.

I do not justify the behaviors that have been described by those who knew Mary Lincoln. If it is true that she chased her husband into the street with a knife, we can only imagine what took place behind closed doors. In 2025, though, negative claims should be balanced with research and rational thinking.

The More Things Change…We now know that certain disorders can cause behavior such as hers (irritability, manic shopping, obsessiveness). Modern historians suggest that she suffered from many things, including bipolar disorder.

This is not an excuse for knife-brandishing. However, a reasonable person will know that it makes a difference. Only recently have we begun to see mental health for what it is.

What troubles me about Carnegie’s presentation of her is that she’s given no opportunity to redeem herself. He does not mention how Mrs. Lincoln volunteered at hospitals during the war, helping wounded soldiers. He does not express sympathy for the pain she felt when her children died. Instead, he slanders her as an ambitious woman who did not know her place.

When I returned Lincoln: The Unknown to the friend from whom I borrowed it, I spotted another book on the same shelf: Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly by Jennifer Fleischner.

Carnegie had mentioned, sparingly, that Mary developed a trusting friendship with Lizzy Keckly, a freed Black woman who had become a talented dressmaker for the important ladies of Washington. Fleischner tells this story in detail, and she does include pieces of information about Mary’s background that could explain her behavior.

Fleischner’s book is honest about Mary Todd’s flaws, beginning in childhood. She is honest about all of these tidbits. It’s amazing the difference that a writer’s tone can make! She managed to sound objective and sympathetic. Is this because Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly was written by a woman? Is it because more time had passed since the subjects of that book lived?

Mary Todd was a ‘loud child’ in an age when children were expected to be seen, not heard. Later, as a young woman, Mary Todd was still loud—and also, a shameless flirt. Having been born into a family of good name, she enjoyed her own ‘Season’ and had no shortage of suitors.

By the end of Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly, the impression I had was this: ambitious Mary Todd was born at a time when there were few ways for ambitious women to achieve anything. Her ambitions were political, and a good marriage was Mary’s only option. She could certainly never run for office.

Knowing all of this, is it really such a surprise that, meeting a man she believed would make it in politics, she pushed hard for that union?

Dreams of the White House

Dreams of the White HouseMary Todd’s dreams began when she was young. Jennifer Fleischner recounts something that Mary, as a child, said to her father, Robert:

Mary’s earliest political ambitions were tied to her father’s success before they were tied to her husband’s. In 1832, when she was twelve, she is supposed to have “begged” Robert Todd to run for President because she wanted to live in the White House.

Mary knew what she wanted when she asked her father to run for President. She was being brought up in a household where politics were discussed at the dinner table. Doubtlessly, she knew about the ‘hot issues’ of the day.

Carnegie writes about young Mary Todd’s ambitions in less flattering words. Note the difference in tone:

Mary was possessed of a high and haughty manner, an exalted opinion of her own superiority, and an abiding conviction that she would one day marry a man who would become President of the United States. Incredible as it seems, she not only believed that, but she openly boasted of it.

He writes about Mary’s political ambition in such a way that her dream is painted as shockingly evil. I suppose that, in her lifetime, such an ambition could seem sinister.

Mary Todd’s flawed behavior would have been influenced by fear of abandonment that began in her childhood. Her mother died of childbirth complications when Mary was only six.

After this loss, Mary sought a maternal figure in her older sister, Elizabeth. She also sought a mother in Mammy Sally, one of the slaves in the Todd home. It was not uncommon for children of slave-owning families to become close with the slaves.

Mary and Mammy Sally developed such a trusting bond that Mammy Sally confided to Mary a dangerous secret. She had been helping runaway slaves who stopped at the Todd home, offering them food and rest as they fled lives of bondage.

Young Mary did not get Mammy Sally into trouble about this, even though she could have. (This is a detail that Dale Carnegie failed to mention). Instead, she offered to take food to a fleeing slave. In her youth, she believed that this would be perceived as good. Mammy Sally explained that runaway slaves were afraid of recapture. The sight of even a white child could cause the man great fear.

Mary’s shortcomings as a wife should be balanced with details like this. Rather than painting her as a manipulative woman who bullied Lincoln into marriage, we should recall that she had moments of compassion. It is important to do this, because she is a significant figure in American history.

He’s Also the ProblemI’m not naive—by all accounts, the Lincolns’ marriage does not seem to have been happy. A lot of drama surrounded their engagement and, eventually, their vows. Before we blame Mary’s temper for all of it, I would remind readers that Abraham Lincoln’s melancholy existed before he ever met Mary.

Lincoln struggled with depression. He’d been born into poverty, and he also lost his mother as a child. He was never a happy man, and while disagreements with Mary would have worsened matters, she was not the sole cause of his misery.

Look at the context; they lived during the Civil War. How could a serious writer try to blame his wife for all of his unhappiness?

Abraham Lincoln did apparently fall ‘out of love’ with Mary Todd, during their courtship phase. This was after they exchanged several letters. Something she wrote revealed an angle of her personality that he didn’t like.

He decided that he could not happily live with her, which is valid. No one should feel obligated to marry someone they don’t think they could live with. Yet he married her, anyway.

My impression is that their relationship was mutually toxic. Abraham Lincoln had depression. Unlike Mary, he’s portrayed as someone who seldom lost his patience. He’s lauded as someone who agreed to marry Mary in order to preserve his honor. He then settled to live an apparently miserable life with a woman who could never shut up.

The dynamics of their marriage seem to have been odd, as well. Fleischner suggests that Mary sought men who would present as a replacement father figure. She found the perfect example in Lincoln:

Lincoln, who was nine years older and possessed the air of a much older man, had these qualities in spades; he moved as if from a central core of being. In him, Mary might have sought the father she never quite had: the striving politician and lawyer whose ambitions were fulfilled and the tenderhearted and steady provider whose home life centered on her.

I sense an imbalance between their personalities, but not in the traditional sense. Mary might have sought in him a father figure. This awkward dynamic meant their relationship, already imperfect, was bound to end in disaster. But it wasn’t all because of her.

What I’m trying to ask with all of this is, Why does Mary seem to get all of the blame for their broken marriage? While we’re at it, Why was Mary offered so little sympathy, even after her husband was killed by her side?

It seems cruel, because the stereotype is perpetuated to this day.

In my next post about Mary Lincoln, I will write more about her time as First Lady. I’ll write about the good things that she did. She did indulge in shopping sprees and create outstanding debt, but that should not be her sole legacy.

She was not all bad. Being ambitious should no longer be a sin in a woman. Let us begin, then, to change how ambitious women in the past are perceived.

It is only just, so that we can move forward as a society.

What to Read Next:

July 29, 2025

The Early Sorrows of Martha Washington

If you’ve been keeping up with my newsletter, you’ve seen me talking about my new project—The Tearoom: First Ladies. It’s going to be a series focusing on the wives of US Presidents.

They will not necessarily be posted in historical order. My inaugural First Ladies post was about Mary Todd Lincoln—read it here:

Mary Todd Lincoln Wasn’t ‘Crazy’

For First Ladies, I will be writing posts in the order of what grips me in the moment. It is, after all, the Muse who decides what deserves the most attention in the moment. Individual projects tend to know when they begin and finish.

Dauntless Martha WashingtonToday, we jump from Mary Lincoln to Martha Washington. I’ve written a post about her mother-in-law, Mary Ball Washington (read it here!) I even wrote a post about the Founders’ daughters, including Martha’s.

Until now, it hadn’t occurred to me that she deserved a spotlight of her own. She certainly does, because her presence proved to be a tremendous source of strength to her husband.

When George Washington was chosen as the general of the continental army, he was not yet President of the United States—but had been unanimously chosen as leader in a war where the odds were against him.

His wife, Martha, was very involved. She even traveled, courageously, to join him at camps near the battle sites. She did this, even when there were rumors that the British might try to kidnap her.

Her story, however, began not with George Washington, but with her first husband. They married when she was in her late teens—but they were very much in love.

Two Different MatchesMartha Dandrige’s romance with Daniel Parke Custis was not conventional. The Custis family were wealthy, and Martha’s parents were only middle-class. Because of this, they had to endure the protests of Daniel’s father.

In spite of this, they chose a life together. It is with Daniel that she would have her children. After Daniel’s death in 1757, his widow received a respectable fortune—especially in the form of land.

Flora Fraser writes in her book The Washingtons:

In accordance with English common law, which obtained in the colony, all [Daniel’s] personal property, minus his lands and slaves, was divided equally between his widow and his children. … Eight thousand acres, the Custis mansion in Williamsburg, and 126 slaves were settled on Martha for life. Should she take a new husband, this dower share, as well as her share of her late husband’s personal property, would come under his control.

Martha would, indeed, take a new husband. The initial motives for George Washington’s pursuit of her were worldlier. It’s no secret that her wealth was appealing to him. Some have questioned whether he was ever in love with Martha in the poetic sense.

His first real love seems to have been a woman named Sally Fairfax. He had been unable to pursue her because she belonged to a wealthy family, while he was of the middle class—and he, it seems, was not brave enough to fight the norm like Martha.

Sally would go on to marry one of Washington’s friends, and after he took a wife of his own, he appears to have committed such yearnings to his past. But there’s no question about it: Martha’s money was attractive to him.

He was interested in using it to renovate his beloved home:

Convenience and SorrowHe could tend his estate at Mount Vernon with the aid of the income from Martha’s dower lands in southern Virginia. … As guardian and stepfather to the rich and well-bred Parke Custis children, he would derive worldly benefit. Washington was to describe Martha, soon after their marriage, as an “agreeable partner.” Five months later, in a letter to the same correspondent, she had become “an agreeable Consort for Life.”

Though it was initially a match of convenience, George would learn to feel tenderness for Mrs. Washington. Later, however, when asked for marital advice by one of his young relatives, he would advise against such sentiments.

Much of the Washingtons’ union remains a mystery. After George’s death, Martha burned most of the letters they exchanged. We can only gather from accounts of their friends, as well as scraps of surviving correspondence, that George and Martha Washington loved each other.

Daniel Parke Custis (1757), John Wollaston

Daniel Parke Custis (1757), John WollastonIn her first marriage, Martha would be strengthened by the pain of loss. This was probably one reason why she was able to accompany her second husband to battlefields.

Though Martha and Daniel were happy, tragedy struck. In motherhood, Martha experienced crippling sorrow. Her first two children were Daniel II (born in 1751) and Frances Parke Custis (born in 1753), and this would be the beginning of the end.

Deaths in childhood in this period were common, and there was no reason why more children should not follow. But only three months after the death of his elder daughter, Daniel himself was abruptly taken ill in July. Despite the attentions of a Williamsburg doctor, he died the following day. … Her husband and two elder children now all lay in the Queen’s Creek plot.

It is believed that Daniel II died of malaria in 1754; his sister’s cause of death is not specified. After Daniel’s death, Martha would be left with only two children—John (known as Jacky) and Martha (known as Patsy).

The losses of her first two children made her a doting, anxious mother, especially when Patsy began to display signs of what historians believe was epilepsy.

The Fortunate StepchildrenFortunately for Jacky and Patsy, their stepfather was genuinely fond of them. Here, he displayed remarkable character. In spite of his hope for heirs, George Washington would have no natural children.

He did not allow himself to mope, instead making meticulous plans for Jacky’s education. George hadn’t had a classical education; he was determined that his stepson should enjoy that privilege.

Washington was committed to finding a cure to Patsy’s ailments. She would live to the age of seventeen. In that short span, her stepfather contacted countless physicians and obtained dubious treatments, refusing to give up hope. He sent his stepdaughter on trips to so-called healing springs, though those trips were fruitless.

Martha and George were not ashamed of Patsy, even when she had her so-called fits. They lived in a time when symptoms of epilepsy were hidden from society. This was not the case for Patsy, who joined her family for public activities, such as shopping and visiting acquaintances.

John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis

John Parke Custis and Martha Parke CustisSeventeen years is not long, but Patsy Custis was happy. She was cherished by her mother until the end. She found in George Washington a stable, comforting father. He is said to have wept bitterly when she passed away.

After the death of Patsy, Martha retreated once more into mourning. She found comfort in her husband and in Jacky, the last remaining Custis child. Though his life also ended tragically, he would survive into adulthood.

Young John Custis proved to be a willful soul. In spite of his stepfather’s hopes, he did not have the discipline to attend a prestigious college. Instead, he proposed to a young lady named Eleanor Calvert. It does not seem as if he asked anyone for advice before proposing. What resulted was a scare for his honor that led to a rushed wedding.

Rushed or not, the marriage seems to have been happy. It provided George and Martha with four grandchildren on whom to dote—Elizabeth, Martha, Eleanor, and George.

Three other grandchildren died soon after birth.

The Final Child DiesJacky’s death would be different in nature, though no less painful to George and Martha. He’d convinced his stepfather to let him join the Continental Army as an aide-de-camp during the Siege of Yorktown.

On the journey there, the young man came down with “camp fever”—likely a disease such as dysentery. He never saw the battle; instead, he was taken upriver to the home of an uncle. There, his mother and wife both attempted to nurse him to health.

Unfortunately, their efforts were in vain; he succumbed to “camp fever” at the age of twenty-six. His widow would move to Mount Vernon with their surviving children, until she remarried.

Though Martha grieved, she did not allow herself to be destroyed. In spite of her losses, she said that it was important to meet darkness with a lively spirit. One of her most famous quotes is this:

“I’ve learned from experience that the greater part of our happiness or misery depends on our dispositions and not on our circumstances.”

Martha married twice. Both marriages placed her in prominent positions. She displayed her inner strength, even in the form of grief for her children.

Her second marriage might have seemed, at the start, to be driven by material reasons. She wouldn’t have predicted the great role her second husband would play in history. I like to think that when she married him, she did know he would be capable of caring for her and her children.

Of Martha’s two husbands, Fraser writes:

In contrast to Daniel Parke Custis, George was Martha’s contemporary. He was, also unlike reclusive Daniel, ambitious, for all his talk of retirement, and of an adventurous spirit. Daniel had had dark good looks. Washington, pale-skinned and with chestnut hair, had fine, classic features. He was, besides, a man of unusual height and with a powerful physique. And last but not least, when Washington came calling, he was a serving officer in uniform.

Martha, in turn, had much to offer George, who would find himself in great need of a strong consort after the war began:

George, for all his physical grace, was nervous at home and stiff and uncertain in company, except with intimates or fellow officers. Martha instilled in him a self-confidence that had hitherto been lacking. Under her tutelage he was to embrace possibilities of friendship and family life.

These men were different in many ways. They had Martha in common, as well as the children who lived longest. George Washington’s story is proof that family is often chosen, not made.

Certain things are far more important than blood.

Only the StartThere was more to Martha Washington’s life than her children, of course. She was active as First Lady, setting standards to a public role that was very new. She would charm guests in her parlor, and admirers would call her Lady Washington.

I will write about other things Martha Washington did. The truth is, she would probably have said that her children were the most important part of her life. All she did, in the end, was for the benefit of her family. That sort of sacrifice is often written off as basic, but it’ll shape a person in many ways.

Both of her marriages were happy in unique ways. Both of her husbands valued her opinion when making choices, even if these choices had different contexts. She is, to me, an example of how strong people can adjust to great life changes.

Like Martha Washington, we all have the ability to get back up when challenges threaten to bowl us over. We’re stronger and more adaptable than we might think.

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you had to reinvent yourself? Do you think that this situation helped you to grow?

What to Read Next:

Shackleton’s Endurance: A Tale of Survival

July 23, 2025

Martha Washington: The First Founding Mother

Read more of my historical articles here!

We can learn a lot from history by focusing on the ladies who were alive at the time, finding out where they stood and how the changes affected them. In the case of American history, the wives of the presidents are an excellent focal point—after all, they were very often in the room when momentous decisions were made. Though they were often quiet, these women had important roles to play as well. That’s why I decided to add the First Ladies to my project this year—I had decided to read biographies of the Presidents in order, and that’s been enjoyable, but there was something missing.

I have now read two books about the Washington family, to use as research for my First Ladies project. The first was The Washingtons by Flora Fraser. This week, I finished Martha Washington: An American Life by Patricia Brady.

As Brady herself says in the final chapter of her book, Martha Washington is probably the most important First Lady, because what she did set an example for all of the future presidents’ wives. The irony is that very little is normally known about her. She has become a shadow to her husband and the things that he did. Thankfully, historians have done some digging; they reveal for us the portrait of an amiable, firm-willed, and courageous woman who proved invaluable to her second husband when he needed a source of strength.

After the war against Britain for independence, the infant nation was stumbling and learning to walk; it was not yet clear what the job of this new leader would entail. George Washington, the unanimously elected first President, had to figure it all out as he went along—matters such as where he would live and how he would be addressed. It was the same for his wife, Martha, but I gathered from Patricia Brady’s book that Martha was more prepared for her role, even if she resented it. (I can’t blame her—she was looking forward to living with George in peace at Mount Vernon, and protested vividly to his being elected President, though she went with him, as usual, where he needed her).

The reason why Martha Washington is a mystery, in spite of her prominent role in history, is a lack of evidence. Her own family seems to be a riddle, a family dating so far back that not everything is documented, and the numerous Marthas and Fannys make genealogy a puzzle indeed. Researchers do not have many letters to work with, either—after the death of her husband, she burned almost all of the correspondence they shared. This action ensured that their romantic life would remain private. It also meant that Martha herself would be shrouded in mystery.

Not all is lost, though; just enough records exist of her life to form an image. Though hazy, this image depicts a woman who loved her family (and was deeply grieved when all of her children died). Martha had enough charm that she was able to win the heart of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, in spite of their social differences—he was of the upper class, and her family were middle class; those two groups did not generally mingle. After Daniel’s death, she took charge of household affairs in his stead, keeping matters organized even during her own period of grief. When her second husband was offered a role where victory was dubious, she supported him fully, though she would worry when he went off to battle. Often, she would follow George out to the uncomfortable battlefields, and she seldom complained about conditions there at all.

I’ve already written one post about Martha and her two marriages, but now that I’ve finished Patricia Brady’s book, I wanted to share further thoughts about the Martha we aren’t told about. She was a courageous woman who took a risk, choosing to be inoculated for smallpox so that she could follow George to the most devastated camps. When she visited, the soldiers would take kindly to her, many learning to view “Lady Washington” as a mother figure when so much in their lives had become uncertain. She was a devoted grandmother who enjoyed purchasing fine gifts for her family, and when George became President, two of these grandchildren would move with them to New York, where Martha would bring them up.

In our world, it might be a bit unusual to pair these qualities with the sort of greatness that stands out in a historical figure. The truth is, there’s great honor in the art of running a house and loving a family. Brady explains:

It’s almost impossible to write the biography of a woman before the twentieth century without writing a lot about daily life, especially for a woman as happily domestic as Martha Washington. To write only of high points and great deeds is to ignore most of human life and the things that give the greatest joy—whether riding around the fields to check on the progress of a new strain of barley for George or Martha’s knitting stockings and hemming hankies for her grandchildren.

As L. P. Hartley wrote, “The past is another country. They do things differently there.”

They do things differently there. I was struck when I first saw that quote from L. P. Hartley—because it makes sense. We might struggle to understand some customs if we hold them to our modern standards. There is a great difference between people who lived in 1776, and people who are alive today. We now have more choices available with regards to our lives and how we would like to be remembered. This doesn’t mean that people in those years weren’t proud of what they did. Besides, if we think of the ease with which disease could beckon death and put an end to families, we can understand why the family unit was the most important thing. It was incredibly fragile.

The Washingtons

The WashingtonsHer first husband is an obvious example of this, for he died only seven years into their marriage. After he died, Martha did not give herself much time to mope. She still had responsibilities, and she took care of them with efficiency. In Daniel’s final memorandum book, his handwriting disappears abruptly after his illness and death. The next page contains Martha’s writing, in almost instantaneous continuation.

She was newly widowed, but she didn’t have time to sit and wallow. The memorandum-book contains a record of an order that she placed from London. It includes a heart-wrenching item that no loving wife would wish to require:

One handsome Tombstone—with the following Inscription and the Arms sent in a Piece of Paper on it, 10 with ‘Here Lies the Body of Daniel Parke Custis Esquire who was born the 15th Day of Oct. of 1711 & departed this Life the 8th Day of July 1757. Aged 45 Years.

Martha was steady and economical, guiding her household, slaves included, into an appropriate period of mourning. Later, she would gracefully guide an entire nation through periods of uncertainty and fear. She did all of this while maintaining the grace and wisdom of a grandmother. She learned to function under pressure, and had a knack for befriending the right people. Her charisma was perfect, for it provided balance to the stoicism of her husband:

Although Washington was sometimes criticized for stiff ceremoniousness, his lady was always praised for her easy friendliness. The president was a man of natural dignity and aloofness, never one for back-slapping camaraderie. – But his wife’s first thought was for her guests. In putting them at their ease, she softened and humanized her overpowering husband, allowing him to relax a bit and show something of the private family man.

Patricia Brady’s book is a quick, enchanting read. Her writing manages, with ease, to complete the image of the first President’s wife. Using letters and other such documents as evidence, she presented the life of Martha Dandridge in a way that I’d never seen before. “Lady Washington” was, for the longest time, a silent image in my head; now I know more about her. This image has come to life, restoring humanity to this admirable woman.

At the end of the book, Brady sums up the significance of Martha Washington’s role. She also comments on her actions, and how they still matter now:

There is no guidebook to help a new First Lady; she must look back at her predecessors to decide how to shape her role and to survive in the limelight. Martha Washington’s imprint on the position has been decisive. As the first in a long line, she invented the role while confronting with grace its inevitable quandaries, successes, and heart-aches.

When George finally retired for good, they were able to spend their final years at Mount Vernon. Martha continued to entertain guests into her old age, old allies and young admirers alike. She spoke to them about history and politics, an unusual activity for women at the time. She was able to answer questions in a uniquely relevant way, because she had been around to see so much of the new nation’s birth.

It is no wonder, then, that many saw her as a mother. Indeed, if there were Founding Fathers, there must have been Founding Mothers, too—and foremost of them all is Martha Washington. From her, we can learn to soldier on through challenging times. She shows us that humans are resilient, and can adapt to situations far from their zones of comfort. She is an example of a doting mother and supportive spouse.

This is what I wanted to learn when I picked up Patricia Brady’s book. I highly recommend it to anyone who would like a different angle from which to examine the American Revolution; you will not be disappointed, I assure you.

June 3, 2025

History in Art, #1

Life of George Washington – Deathbed (1851) by Junius Brutus Stearns

Life of George Washington – Deathbed (1851) by Junius Brutus StearnsDoctor, I die hard; but I am not afraid to go; I believed from my first attack that I should not survive it; my breath can not last long.

Haunting and poignant, these are George Washington’s final recorded words, spoken as life slipped from his body.

His death occurred on December 14, 1799. He had lived to the age of sixty-seven. In life, he had built a reputation as a strong and capable leader, fending off the strongest army with poorly trained but determined soldiers. He was now regarded as almost superhuman.

However, in these final moments, illness reminded him of his humanity. We all become ill sometimes—and at one point, it will be the last time.

These final words were recounted by Washington’s secretary, Tobias Lear. Lear was in the room with Martha and the physicians, waiting for the inevitable.

According to Lear, Washington continued: “Do you arrange and record all my late military papers—arrange my accounts and settle my books, as you know more about them than any one else, and let Mr. Rawlins finish recording my other letters which he had begun.”

Washington’s body, as he spoke, was weakened by infection. An 1851 oil painting by Junius Brutus Stearns aspires to capture these moments. It is a gripping piece, heavy with emotions like awe and finality.

Washington’s election as the first President was nearly unanimous (except for Washington himself, who did not want the title). His beloved home, Mount Vernon, was a lifelong project. Today, it remains—an elegant, dignified reflection of its master’s spirit.

It can be thought of as our house, the home of the people. Ironically, Washington had no natural children of his own. His adopted son and daughter—children of his wife, Martha—both died young. He has left an impressive legacy, all the same.

His Excellency by Joseph J. Ellis describes the almost trivial circumstances which led to Washington’s illness. They began after he went riding on a cold, December day in 1799:

Despite a storm that deposited a blanket of snow, sleet, and hail on the region, Washington maintained his regular routine, riding his rounds for five hours in the storm, then choosing not to change his wet clothes, because dinner was ready upon his return and he did not wish to inconvenience his guests with a delay. The following day he was hoarse, but insisted on going out in the still inclement weather to mark some trees for cutting. He presumed he had caught a cold, and felt the best treatment was to ignore it: “Let it go as it came,” as he explained.

Let it go as it came—but it did not. The weather was severely cold; due to his advanced age, Washington was perhaps more vulnerable to the maladies of cold.

That night, he found himself suffering from shortness of breath and a severe pain in his throat. He woke Martha:

Word went out at dawn to fetch Lear and Dr. James Craik, Washington’s personal physician and friend for over forty years. Craik immediately diagnosed Washington’s condition as serious, possibly terminal, and he dispatched riders to bring two local physicians to Mount Vernon to assist him in prescribing treatment.

But nothing could be done. As was the custom, physicians bled him in hopes that the infection would be flushed out. Today, we know that the human body does not work like that. Many believe that he died faster because of the amount of blood that he lost.

I have twice visited Mount Vernon, twice seen the room in which he died, decorated in such a manner that it seems I stepped back in time. The painting is a powerful reminder that times change, medicine advances, and heroes remain bright in our nation’s history. It is more impressive, even, than the real thing.

May 23, 2025

My Thoughts on Pope Leo XIV’s First Homily

*The featured image for this post is Pope Leo XIV when he visited the tomb of Pope Francis.

Last week, I published a post that I was writing while watching Pope Leo XIV’s inaugural Mass at the Vatican. That post ended just before he was to begin his homily. Click here to read the transcript.

While writing last week’s post, I considered including my thoughts about the homily in the same post. However, I realized that it would be a very different matter. Such a topic merited its own post, a place where it can have its unique commentary.

These are my humble thoughts about some notable things the Pope said. For the sake of the length of this blog post, I will not comment on everything, though if there’s a matter you would like to discuss, feel free to leave a comment about it.

Pope Leo XIV became emotional after receiving the Ring of the Fisherman.

Pope Leo XIV became emotional after receiving the Ring of the Fisherman.In the past few weeks, members of the Church have experienced many emotions. The death of Pope Francis filled our hearts with grief. In those difficult hours, we felt like the crowds that the Gospel says were “like sheep without a shepherd” (Mt 9:36).

From the beginning, Pope Leo XIV acknowledged his predecessor. I found it touching because I, like many, do miss Pope Francis. I thought often about how Pope Francis, after such a long stay in the hospital, managed to wait. He did not go to the house of the Father until after Easter. It feels as if he did this on purpose, so that we could have joy during Holy Week.

Did Pope Francis know his time was nearly up? Perhaps he had that thought in mind when giving us his final blessing.

My family and I watched this Mass, and the celebration that followed, on television. I listened to the bells ring joyously over St. Peter’s Square. They rang for a long time, a striking sound. It never crossed my mind that this would be the last time they would ring with that Pope alive.

The next time I heard those bells on television, the Pope was at peace. The grieving Church was orphaned, waiting to find out who God had in mind for the next pontiff. I wondered every day, and even then it never occurred to me that Pope Francis’ successor would be American.

Pope Francis giving his final blessing to the faithful on Easter Sunday, 2025

Pope Francis giving his final blessing to the faithful on Easter Sunday, 2025Pope Leo acknowledged this. His words were: “we received his [Pope Francis’] final blessing and, in the light of the Resurrection, we experienced the days that followed in the certainty that the Lord never abandons his people but gathers them when they are scattered and guards them “as a shepherd guards his flock” (Jer 31:10).”

Next, Pope Leo acknowledges the importance of the faithful during a conclave, and especially their prayers. He expresses this thought poetically:

“Accompanied by your prayers, we could feel the working of the Holy Spirit, who was able to bring us into harmony, like musical instruments, so that our heartstrings could vibrate in a single melody.”

Pope Leo then expressed his hope to be a good shepherd:

“I was chosen, without any merit of my own, and now, with fear and trembling, I come to you as a brother, who desires to be the servant of your faith and your joy, walking with you on the path of God’s love, for he wants us all to be united in one family.”

Do not overlook the part where he asks for unison.

The Church has had trouble in recent years. Many opposing ideas have threatened disorder. It is truly a great promise that ‘the gates of hell will not prevail against her’ (Matt. 16:18). We should not be arguing, but prayerfully discerning the will of God—and it’s not so difficult to know this. He desires for us to love one another.

Too many people attempt to keep their faith under wraps. It is certainly valid to serve Him on one’s own, by means of personal devotions and sacrifices such as fasting. However, we cannot forget the value of living the Christian life together. We were not created to be alone.

I could not express it any better than Pope Leo did, in this striking statement:

“Love and unity: These are the two dimensions of the mission entrusted to Peter by Jesus.”

Love and unity. God desires for us to love, even when it seems like we can’t. We are encouraged to listen to one another with patience and compassion. All humans, even those who have strayed, were created by God.

As the late Pope Benedict XVI stated:

“Each of us is the result of a thought of God. Each of us is willed, each of us is loved, each of us is necessary.”

We sometimes have the idea that love is passive and cannot bring about great change. This is simply untrue. True love is not passive. Love can require great effort. It asks us to put aside our prejudices. It moves us to offer gifts—even immaterial gifts, like time and a kind word—to individuals that we don’t think deserve them.

Love improves us, and even if it does not happen immediately, the person being loved does benefit from it. Why? Because God is love. God is not passive. We cannot always see Him, but He never tires of loving us. We should strive to imitate Him in doing the same.

The homily urges us to go forth and spread the Good News. Another poignant phrase from Pope Leo XIV calls for unity:

“Brothers and sisters, I would like that our first great desire be for a united Church, a sign of unity and communion, which becomes a leaven for a reconciled world.”

What does this mean? It’s impossible to ignore that, due to various reasons, some Catholics have been arguing amongst themselves. Rather than spreading the Gospel, they try to one-up each other. It is a bad look for outsiders who might be interested in the Church. If we do not show love for each other, how can we compel a possible convert to come near?

The human soul seeks peace in the arms of God. I can understand why many would avoid a place of worship where strife exists.

Rather than being unkind to converts, we should welcome them and share the faith we love. Rather than obsessing over types of Mass (I consider the Novus Ordo and Latin to both be valid), we should be thankful people are compelled to attend. It’s human to have preferences, but I’ve encountered too many people who sneer at one form or the other.

Rather than initiating arguments, should we not take time to learn what the other party believes? As stated in my previous post, I’ve learned much about God by conversing with people who don’t worship in the same way I do. Through their help, I have come to enjoy a closer relationship than ever with the Lord.

Let’s focus our energy on becoming fishers of men. Cliquish behavior does not call to the broken. Only love can lure the shattered, for love is the greatest of balms. Love is Christ; love saves.

I believe our new Pope understands this. It is very similar to what Pope Francis called for. Pope Francis’ words were often taken out of context. I dare say that his message was the same: We must love one another like Christ loved us (John 13:34-35).

This month, Google searches for ‘how to become Catholic’ have begun to rise. I challenge you to educate yourself about your faith. Be prepared to answer questions, as they will surely come.

During this pontificate, there is a high likelihood that you will meet people with questions. We should be prepared to give reasons for our faith. Let us be warm and welcoming to the people making those Google searches.

It is time to be unified again. It is time to rethink what it means to do things as Christ did, with love.

Did something in particular strike you about Pope Leo XIV’s homily? I would love to hear from you!

May 18, 2025

Pope Leo XIV & New Beginnings

As I edit this blog post, the television is on. I’m watching as Pope Leo XIV rides in the Popemobile through St. Peter’s Square. This is the first of many times that he will do this.

He is waving at people from all different countries. I see American and Peruvian flags in the crowd. They both make me feel warm inside; my mother is Peruvian and I was born and live in the USA. Diplomats and world leaders have traveled to Rome to attend this inaugural Mass.

At this moment, the world is curious and optimistic about the 267th Pope of the Catholic Church. It’s not every day that we are presented with blank slates in which to make history.

Ten days ago, that famous chimney sent forth white smoke. Believers all over the world were filled with joy; the Church had been orphaned since the death of Pope Francis.

During the Conclave, names of specific Cardinals were put forth as favorite candidates. I always considered this a bit silly; the Church does not work like Presidential elections. Polls are not as useful in this context.

What takes place during a Conclave is secret. Those inside take vows of silence, at risk of excommunication. If no one can go in to eavesdrop, I hardly think our speculation will do much good.

It’s fair to say that everyone was surprised when Cardinal Prevost stepped out as the new successor of St. Peter. The common opinion was that there would not be an American Pope anytime soon. I am still surprised that the 267th Pope, elected a week ago, is an American. With a Peruvian mother, living in the country where Pope Leo XIV was born, I feel that I can see a unique angle of his papacy.

I intend to use this angle and be open with my faith; to begin with, I wanted to reintroduce myself as a Catholic. Twenty years ago, at the age of fifteen, I chose to be baptized in the Catholic Church.

It seems like a remarkable coincidence that an American Pope should begin his papacy on this significant personal anniversary.

I want to write about my faith journey and what it means to me. I used to do it on this blog, but became discouraged because I did not consider myself to be knowledgeable enough; I did not feel Catholic enough to put forth worthy commentary. I now understand that all of our voices deserve to be heard, and if I do not understand something, I can learn. We never do finish learning.

We are discouraged from speaking about politics and religion, for fear of stepping on toes. I am going to assume my readers are able to respect my faith.

If you’ve been following my Substack blog, you’ve seen my historical articles. American history is important to me. This opportunity is perfect! I have a chance to write about American history as it is happening. Why should I refrain?

I was baptized in the 2005, after the death of Pope John Paul II. I’m not a convert; I was given the chance to choose when I was old enough. I had been exposed to Catholicism and its traditions by my grandmother, who would come from Peru to visit with prayer books, holy cards, and statues. She would keep these on her bedside table, where they fascinated me.

After Pope John Paul II died, my mother remembered that I hadn’t been baptized, and asked me if I would like to be. That spring I celebrated my Baptism, Holy Communion, and Confirmation. At this time, Pope Benedict XVI was elected. I was alive for the four most recent Popes in history, but had only been baptized for three of them.

The fact that I chose baptism at an age when I understood it, probably helped me love the faith more. I’ve met a lot of cradle Catholics who don’t seem to think much about the Church’s beauty. It seems that a person who grows up in an environment can sometimes (not always) become desensitized to tradition.

I also have periods in which I lose interest; I’m by no means full of perfect zeal. I constantly have phases when I forget to care about things of God, but I do go back to Him.

As flawed humans, it can be difficult to love something we cannot see. Blessed are those who believe without seeing. We cannot see air, but there’s evidence of it when wildflowers sway in its presence. A thing can be invisible and still make an impact on objects around it.

In a like manner, a Person can be ‘invisible’ to the sight, yet still sensed by a seeking soul. Those who wish to encounter Him, can ask; in humility, they will find Him.

In my mind, three things are true: God is real. God is not always visible. I could not be happy without God.

Religion is difficult to speak of, because many are not able to discuss opposing ideas calmly. While I don’t plan to put forth multiple posts about dogma, there are many interesting events in church history! Certain Saints’ stories are inspiring, even for people who don’t believe. A lot of traditions are misunderstood, yet beautiful after explained.

It is my hope to offer knowledge. It is not my mission to make you believe, as faith can only come from God. The Internet is a great place to find different perspectives. I, for one, have enjoyed learning what friends of different religions and philosophies believe.

Though we are trained to think people of opposing beliefs cannot be friends, the truth is that my most fulfilling friendships have been with people who approach the world differently. There is no need to pick a fight. I might not feel inclined to believe everything my friends do, but I’m always honored when they take time to explain something that was foreign to me.

I know this world has become hostile, intolerant, fearful. People are quick to anger when they encounter something they disagree with. Again, it is not my intention to force a belief down your throat.

I do know that in the coming years, there will be a rise in people wanting to learn about Catholicism. They might not want to convert, but I hope that, since humans are curious by nature, there might be questions in their hearts. It’s my intention to inform, entertain, and celebrate the special time we are living now.

As I write this final paragraph, Pope Leo XIV is about to soon begin his homily. I am eager to hear his words; I’m also eager to share them.

Thank you for reading this post. I look forward to experiencing history with you, and hopefully, having engaging discussions. There is great joy in learning together. Let us not waste this opportunity.

December 30, 2024

Book Review: Once Upon a Wardrobe by Patti Callahan

I finished reading this last night. I had started in October but became sidetracked due to life things; I’m glad I came back to it during the Christmas season, because it is a perfect book to read during Advent.

George is a sickly child who is aware that he won’t live to adulthood. He finds solace and escape in C.S. Lewis’ book The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. He asks his older sister, who is a college student, to find the author at his home in Oxford and ask where Narnia came from. She is willing to do anything for him, so she agrees.

His sister, Margaret, is skeptical of anything that isn’t factual like math. She has a sick brother she’s going to lose any time – how can she have hope? How can she daydream? But as she sits down for regular conversations with Professor Lewis, she finds her heart beginning to change. Maybe George was right all along…

This book very nearly made me cry towards the end. It helps us see grief, especially expected grief, from a different perspective.

It’s a short read; I do recommend it.