J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2122

January 14, 2011

Austerity and Monetary Policy

At some deep level, a lot of us believe in hubris, nemesis, and retribution--in spite of the fact that there is no evidence for and an awful lot of evidence against the proposition that the arc of the universe tends toward justice. Paul Krugman meditates on how this belief has messed up our analysis of the current slump:

Monetary Morality:

A further thought inspired by the meditations that led me to today’s column: I think I now understand the otherwise weird resurgence of paleomonetarism in the midst of a prolonged liquidity trap. It’s not really about analysis, it’s about morality.

You see, if you’re the kind of person who views being taxed to pay for social insurance programs as tyranny, you’re also going to be the kind of person who sees the printing of fiat money by a government-sponsored central bank as confiscation. You may try to produce evidence about the terrible things that happen under fiat currencies; you may insist that hyperinflation is just around the corner; but ultimately the facts don’t matter, it’s the immorality of activist monetary policy that you hate.

And this is also why politically conservative economists arguing for something like nominal GDP targeting, and pleading with their perceived political allies to stop talking nonsense, are going to be disappointed. If you’re in the intellectual universe where monetary policy is to be evaluated by results, you’re already out of the true believers’ moral universe. At a fundamental level, Milton Friedman and John Maynard Keynes are on one side; Ron Paul is on the other. And it’s not a debate in which evidence really matters.

January 13, 2011

Four Rules of Strategy

Never draw to an inside straight. Never fight a land war in Asia. Never go up against a Sicilian when death is on the line. And never, never, never fight a war of lurk-and-pounce against a race of alien spiders.

Over at tor.com Jo Walton--author of the Best Dragon Novel of All Time and of the Damnedest Version of the Tale of Sir Launcelot du Lac I Have Ever Read and company are talking about Vernor Vinge's A Deepness in the Sky--which may be the Greatest Science Fiction Novel of All Time.

Among other things, they are talking about the clues that Vinge drops as to [spoiler], and whether anybody un-Focused could possibly figure out in advance that [spoiler], [spoiler], and [spoiler]. They have come up with only two clues: "steganography" and "I'm not a machine?"

There is a third, at the start of the kidnapping sequence:

He reached out to Smith, the tremor in his head and arms more pronounced than ever. "There has to be a way to find them. There has to be. I have computers, and the microwave link to Lands Command." All the resources that had served him so well in the past. "I can get them back safely. I know I can."

Smith was very still for a moment. Then she moved close to him, laid on arm across Sherk's shoulders, caressing his fur. her voice was soft and stern, almost like a soldier bracing another about lost comrades. "No, dear. You can only do so much"...

The U.S. Government Brings the Health Insurance Industry 32 Million New Customers

Why the insurers haven't told the Republican members of the House of Representatives to cool it on ACA "repeal" is something I do not understand.

Sarah Kliff:

Investors see health law's potential: SAN FRANCISCO – As Republicans push forward on repealing health reform, planning the law’s demise, a different conversation is happening among thousands of health care investors gathered in San Francisco for this week’s J.P Morgan Health Care Conference: how to capitalize on health reform’s new business opportunities.The Congressional Budget Office estimates 32 million Americans will gain health insurance by 2019 if the law stands. For health insurers, that represents a potential boon for both their individual market business as well as in the Medicaid market, where states regularly contract with private insurers to manage care.... [R]egulations released this year have been relatively industry-friendly, increasing stability, and the health reform’s new business opportunities are beginning to look more tangible....

At the J.P. Morgan Health Care Conference in San Francisco this week, major health insurers outlined the major expansion opportunities they see in the health reform law. Aetna is exploring how to capitalize on the individual market, expected to boom in 2014 when Americans must purchase health insurance or pay a fine. “We have major efforts underway to strategize on how to take advantage of those opportunities,” said the insurer’s CFO, Joseph M. Zubretsky, in a presentation to health investors. “We’re clearly understanding the risks…but with millions coming on to the health exchanges, one needs to not only balance risk but really understand the opportunity for growth that exists in this market place.” “We’ll really be ready for the individual market as it evolves,” Humana CEO Michael McCallister said. “We’re likely to have 51 flavors of this.” In the wake of the health reform law, Humana sees opportunities both in its Medicare and individual market products.

Medicaid also presents serious growth opportunities. The program will expand to cover everyone below 133 percent of the federal poverty line and, as the Wall Street Journal first reported, insurers are actively pursuing contracts with states to manage their Medicaid plans. As Aetna’s Zubretsky put it, “Medicaid is going to be a critical component of our business model with 17 million joining that program.” Molina Healthcare, a company that has a large book of business in Medicaid, listed the millions of Americans who will become newly-eligible for Medicaid as a “health reform growth opportunity” in an investor presentation....

Wellpoint spent much of last year sparring with the Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius over a double-digit rate hike and policy recissions, at one point writing a letter to President Barack Obama accusing the president of spreading “false information.” Speaking on Monday, CEO Angela Braly framed health reform as a collaborative project with the Obama administration. “We’re working collaboratively with the administration and intend to continue to do so,” she said. “We have brought to them input both from our voice and our consumer advisory group, and they give us a lot of feedback. Our job is to work very carefully with the administration and Sebelius to get the answers to our consumers.” For their part, Wellpoint has found the new regulations manageable. While they expect the new medical loss ratio regulations, which require insurers to spend at least 80 percent of premiums on medical costs, to have a negative impact on their business, it won’t be unmanageable. “We’ve sized about a $200 to $300 million headwind taking our existing book of business and overlaying the MLR rules,” Wellpoint CFO Wayne Deveydt said. “We’ll modify commissions paid to brokers… Brokers will continue to be viable but there’s a shared responsibility [for the new regulations].”...

Health insurers spent barely anytime discussing Republicans’ repeal efforts. Aetna’s Zubretsky touched on the subject briefly only to say that Republicans understand that a rifle shot approach to tearing out specific health reform provisions, particularly the individual mandate, would not bode well for their business. “The unintended consequence of repealing and replacing part of the legislation is the biggest risk here,” he said. “If guaranteed issue stays but the enforceable mandate disappears, you need another mechanism to make the costs in the risk pool work.” Zubretsky said Aetna has been in touch with the GOP on the issue and “believe the Republican leaders we’ve been talking to understand the consequences of decoupling the mandate from the guaranteed issue.”

The Trend of Resource Prices

Tyler Cowen:

Marginal Revolution: How robust are Julian Simon's predictions?: Not the ones about population, the ones about falling real resource prices.

Here is a simple model: it is easier to transfer technologies of resource extraction than it is to transfer most other technologies. In other words, Nigeria has low TFP but still their oil rigs work pretty well. If that's true, when the wealthiest economies are opening up a commanding lead in terms of living standards, real resource prices should be falling. Nigeria can supply a lot of oil without demanding very much. When most of the growth is catch-up growth, the poor countries demand more resources but supply technologies are not racing so quickly ahead. Real resource prices are more likely to rise.

There is a long history of falling real resource prices, but is this simply reflecting the fact that the last three hundred years don't offer many periods of catch-up growth? Now, an era catch-up growth seems to be upon us. So why should we be so confident that Simon's predictions will continue to hold?

This Week Has Bad News on the Unemployment Front

Jefferey Bartash:

U.S. jobless claims climb 35,000 to 445,000: WASHINGTON (MarketWatch) - The number of U.S. workers who filed new applications for jobless benefits jumped 35,000 last week to 445,000, the highest level in more than two months, but a government official attributed the sharp increase largely to administrative backlogs. Some people don't file claims right away during the holiday season and state unemployment offices are open fewer hours, leading to paperwork delays. Economists polled by MarketWatch had expected initial claims in the week ended Jan. 8 to fall to a seasonally adjusted 405,000. The four-week average of new claims rose a much smaller 5,500 to 416,500. The moving average is considered a more accurate measure of employment trends because it evens out fluctuations in the weekly data that can give a distorted picture of the labor market. Continuing claims, meanwhile, fell by 248,000 to a seasonally adjusted 3.88 million. Altogether, 9.19 million people received some kind of state or federal benefits in the week of Dec. 25, on an unadjusted basis. That was up 422,523 from the prior week.

The End of Procyclical Labor Productivity?

Nick Rowe:

Worthwhile Canadian Initiative: US Productivity Exceptionalism: I could understand if the US had the worst output and employment during the recession. I could fake up some explanation. "The US, with the bursting of its house price bubble, was the epicentre of the financial crisis, blah, blah...". I could understand if the US had the best output and employment during the recession. I could fake up some other explanation. "The US, with its free market economy and labour mobility, is remarkably resilient to shocks, blah, blah...". What I can't understand is why the US had the second best output, and yet by far the worst employment. That would require two fake explanations, and it would be hard to make those two explanations consistent.

Each of us thinks our own country is normal. We try to explain why other countries are different. That's especially true if our own country is a large country, like the US. But when you compare the US to all the other G7 countries, you see that it's the US that is abnormal, and in need of explanation.

Ignore the US in Stephen's graphs, and everything looks normal. Some countries did worse than others, and the countries that did worse on GDP tended to do worse on employment. You get roughly the same ranking on either measure. Moreover, the decline in GDP was about two or three times as big as the decline in employment. That's what we would expect, from Okun's Law. It's the US that doesn't fit the pattern. The US is abnormal, and in need of explanation.... [I]n the US [labor productivity] didn't fall at all. Labour productivity actually increased. GDP fell a little over 4%, peak to trough, and employment fell nearly 6%, so the GDP/employment ratio increased by over 1%.... Why did US productivity increase during the recession? Why doesn't your explanation also apply to the other 6 countries?

Why is the US an exception?

I am not sure, but it happened in the last recession as well. As I wrote back in 2003:

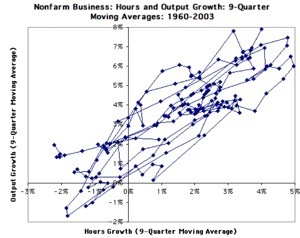

Things have been different, however, in this recession (and to a lesser extent in the preceding early-1990s recession). The standard relationship between output growth and hours worked has gone substantially awry. See that branch poking out of the scatter diagram on the left side? That's the most recent data. (The smaller twig pointing out below and to the left of the branch is from the early-1990s recession and recovery.)

The fact that falling hours have been accompanied by rapidly-rising productivity is what has given us not a jobless recovery but a massive job-loss recovery. The normal pattern we would expect from the past two years' output growth would be that employment and hours would have been nearly flat. Why the different pattern this time? We think that it is because firms are no longer "hoarding labor" when times are slack because the industries losing jobs no longer expect employment to bounce back.

This means that we no longer have any confidence that we understand the cyclical pattern of productivity growth--which means that we have little ability to translate the (high) productivity growth numbers we see into information about what the underlying long-run trend growth rate of the economy is.

Why is this? Why have firms changed their behavior? Let me turn the mike over to Erica Groshen and Simon Potter of the New York Federal Reserve Bank:

Erica Groshen and Simon Potter (2003), "Has Structural Change Contributed to a Jobless Recovery?" (New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York): The sluggishness of payroll growth during the 1991-92 and current recoveries stands in sharp contrast to the vigorous rebound in employment during earlier recoveries (Chart 1). To be sure, these earlier recoveries had rocky moments, with occasional jobless intervals. At the start of any recovery, many employers will delay hires or recalls for a time to be certain that the increase in demand will continue. Nevertheless, although the job market resurgence in the past may often have lagged the output recovery by one quarter, only during the two most recent recoveries has the divergence between job and output growth persisted for a longer period. The divergent paths of output and employment in 1991-92 and 2002-03 suggest the emergence of a new kind of recovery, one driven mostly by productivity increases rather than payroll gains....

Recessions mix cyclical and structural adjustments. Cyclical adjustments are reversible responses to lulls in demand, while structural adjustments transform a firm or industry by relocating workers and capital. The job losses associated with cyclical shocks are temporary: at the end of the recession, industries rebound and laid-off workers are recalled to their old firms or readily find comparable employment with another firm. Job losses that stem from structural changes, however, are permanent: as industries decline, jobs are eliminated, compelling workers to switch industries, sectors, locations, or skills in order to find a new job. A preponderance of structural--as opposed to cyclical--adjustments during the most recent recession would help to explain why employment has languished during the recovery. If job growth now depends on the creation of new positions in different firms and industries, then we would expect a long lag before employment rebounded....

The difference from the pattern of the early 1980s is quite stark: now, the industries cluster heavily in the two structural quadrants. Most of the industries that lost jobs during the recession—for example, communications, electronic equipment, and securities and commodities brokers—are still losing jobs. Balancing the structural losses of these industries, however, are the structural gains of others. For example, nondepository financial institutions, an industry grouping that includes mortgage brokers, added jobs during both the recession and the recovery...

It used to be that labor productivity was procyclical: businesses would hold onto workers in downturns even when there wasn't enough for them to do--would put them to work painting the factory--because the match between businesses and their skilled, experienced workers was valuable, and businesses did not want to see their skilled, experienced workers drift away in a temporary downturn and then have to go through the expense and loss of training new ones. We know this because when the overall unemployment rate rose higher, and so there were fewer places for laid-off workers to drift off to, labor productivity became less procyclical.

That era is over. (Well, there is still a very small sign of it in manufacturing.)

These days U.S. labor productivity looks to be countercyclical: firms take advantage of downturns in demand to rationalize operations and increase labor productivity, pleading business necessity in the face of the downturn to their workers.

It seems fairly clear to me that calling this "structural change" is somewhat of a misnomer. Structural change is when workers find jobs in expanding industries. That happens overwhelmingly during booms. For workers to lose jobs in contracting industries and to not find them in expanding industries is not "structural change" but rather something else.

If we were to pump up demand we would pump it up in expanding industries, and so accelerate rather than obstruct labor reallocation.

January 12, 2011

Is This a Real Vegetable?

Mitch Daniels, Deficit Arsonist: "The Building Was on Fire Anyway!"

Via Mark Thoma:

Economist's View: "Bush, the Bubble, and the Deficit": Indiana's Republican Governor Mitch Daniels tries to blame the 2001 recession for the deficits that occurred under president Bush. David Leonhardt sets the record straight:

...Here is [Wolf Blitzer] interviewing Mitch Daniels...:

BLITZER: A columnist in The New York Times wrote recently ... saying if you decide to run for president, you need to explain .. “why as budget director, [you] did not try to prevent the Bush administration from turning a big surplus into a huge deficit, not just through the war, but through tax cuts and other policies, too... If he runs for president, that question deserves to be a big part of the vetting.” Do you want to respond to that?

DANIELS: You know, the nation went into a deficit then because the bubble burst. We had a recession. It wouldn’t have mattered what policies you tried to implement. ...

That is not quite right. When President Bill Clinton left office in 2001, the Congressional Budget Office was forecasting an average annual budget surplus of $850 billion for 2009 through 2012...

The bursting stock-market bubble and recession that Mr. Daniels mentions erased a little less than $300 billion of the surplus. The Bush administration’s policies — including the tax cuts, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the Medicare prescription-drug program — erased another $673 billion. ...[I]t is not true that “it wouldn’t have mattered what policies you tried to implement.” The Bush administration’s policies did more than twice as much damage to the budget as the recession did.

Here's a bit more of the interview. If spending cuts are so important to Republicans, Blitzer asks, why did the government get larger under Bush?:

BLITZER: ...the national debt doubled during the eight years of the Bush administration...

DANIELS: Well, nobody is happy about that. ...

BLITZER: But the government turned out to be during those eight years a lot bigger than it was when he started?

DANIELS: It did and you know, we don't have to agree with that to agree --

BLITZER: Who was to blame for that? Because Republicans have been saying forever, the government has to be smaller. The national debt - there's going to be balanced budgets, but during the eight years of the Republican administration and you work for the president. It got bigger the government and the debt doubled.

DANIELS: I think there is plenty of blame to go around and we can spend the next couple of years trying to apportion it and assign it between Republicans and Democrats and the economy, which two bubbles popped and led to a plunge in revenues, but --

BLITZER: For six of those eight years, the Republicans had the majority of the House and Senate as well.

DANIELS: Yes, some of my biggest fights were the members of our own party. ... So I will just say that the choices that were made in those years were not all accurate, not all good ones...

Buce Watches Justice Kagan

I don't think he likes what he sees very much. This one goes to 11 on the snark meter:

Underbelly: Justice Kagan's Torture Memo: "It Can't Possibly Mean That": [T]he issue is a precise point of statutory interpretation (so precise you could be excused for wondering why the Court messes with it at all)... does the debtor get to deduct expenses for a car payment when he owns no car? On a hasty reading, the uninitiated reader might conclude that "yes, he does get the deduction." He might also conclude that the result is a bit silly but clarity and coherence have apparently never been part of Congress' brief.

Justice Kagan was not so easily fooled. She reads the statute a second time and finds that "the key word...is 'applicable'," and that the deduction just wasn't applicable.... From a more spacious vantage, however, the case really needs to be filed not under "bankruptcy" per se but under "statutory interpretation." And here, you might be tempted to wonder whether what they learn at the Harvard Law School is the art of torturing the statute until you extract a confession.

There's a back-story here that you'd never suss out of the opinion itself. Specifically, the language in question comes from the famous-all-over-town bankruptcy amendments of 2005, which made it much tougher for ordinary folks to get bankruptcy relief. Whether that's A Good Thing or not is the kind of issue on which, inevitably, tastes differ. But another issue, apart from substance, is quality of the statute as a piece of draftsmanship. Here there is much wider agreement: it's a mare's nest, a dog's breakfast, a can of worms, just about anything but the cat's meow.... No surprise, then, that an kind of cottage industry has developed in the lower courts since 2005 which you might call Saving Congress from Itself--more precisely, trying to read some sense into a statute which often doesn't make any sense. But this endeavor has not been purely technical. Rather, there seems to have developed a sense among the lower courts that what Congress intended to do was jam it to the debtor good and hard, and that if Congress didn't get it right the first time, then we must help them. Bankruptcy lawyers have fashioned a new canon of statutory interpretation: if the statute seems to favor the creditor, apply the statute; if it seems to favor the debtor, assume it's a mistake and favor the creditor anyway.

I wouldn't put Kagan in quite that camp. Her reading seems more rooted in the "Congress couldn't have said anything that stupid" school. And she obviously has a lot of company: the whole crew is on board. The whole crew, that is, with one exception: Antonin Scalia who ways in with a typical blunt assertion of a kind of plain-meaning rule (whatever Scalia may be willing to torture, you'd have to say that statutes are not on the list).... So we are left with the ironical conclusion that Justice Kagan, late darling of the left, begins her Supreme Court career by putting money in the pocket of the credit card companies. while the last man standing at the pass in defense of the beleagured debtor is Antonin Scalia...

Me? I'm tickle to see eight justices signing up for the principle of statutory implementation noted by Robert Unger in his article on the "Critical Legal Studies Movement": that if a statue is enacted as part of the political victory of the cowmen over the farmers, you interpret the statute to the benefit of the cowmen and to the detriment of the farmers. (OK, OK. Unger is not making an "Oklahoma" reference--it's not "farmers" but rather "sheep-herders.")

You Know, I Think Having Had Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs (and Others) as My Teachers Gives Me an Unfair Advantage

Ryan Avent gets puzzled as he tries to work his way through the causes of unemployment:

Labour markets: Sticky, sticky wages | The Economist: what we see is a two-track labour market. Workers who never lost their jobs... have potentially enjoyed pay increases. But... jobless workers... have struggled to find work and who can generally only do so at a significant wage cut relative to their previous pay.... I mentioned a few explanations ventured by Rob Shimer....

One big issue is the problem that nominal wages aren't very flexible in a downward direction. Another issue could be that since existing firms aren't motivated to hire new and cheap workers, new firms are needed to absorb jobless workers, but new firm creation is hampered by tight credit conditions. Mr Shimer also speculated that unemployed workers could somehow be different—uniquely unskilled or improperly skilled—or they could be pinned in place by housing conditions in particularly bad job markets....

Why wouldn't firms swap out older, more expensive workers for the cheaper unemployed ones available to them? One possibility is that firms are worried about the disruptive impact of such workforce turnover and have decided that it's better to keep employing existing labour at existing wages...

Bingo. That appears to be the answer--that has been the rule for nearly two centuries: firms are scared that swapping out their current workforce for a new one or even cutting nominal wages by threatening to swap out their current workforce for a new one is devastating for worker morale and thus productivity.

The answer is, as Ryan points out, that the currently-unemployed need new or expanding firms to hire them, and:

Robert Hall argues that credit conditions remain tight for new businesses, who are the big job creators.

Or it could be that jobless workers are simply much less productive than those who continue to work.... But... why [did] firms [have] them on payrolls before the recession[?]... The data seem not to point toward structural factors as the primary driver of unemployment.

Perhaps the problem is a shortfall in demand, which is preventing existing firms from expanding. It could be that the real interest rate simply isn't low enough to induce firms to invest in new plants and equipment--investments that would produce corresponding jobs.

It is at this point that Ryan should have noted that nominal demand is now 8% below its pre-2008 trend. Surely if something were to suddenly and quickly without harming worker morale reduce the level of nominal wages by 8%--so that real demand were back at its trend--we would magically discover that all those "low-productivity" workers were very employable.

Well lo and behold, that is how it worked in the Great Depression. Exchange rate depreciation is--if you are a small open economy--an extremely easy way of reducing your nominal wages in world prices without harming worker morale.

Could there possibly be any reason to think that things are working any differently today?

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers