J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 1085

January 29, 2015

The Rebalancing Challenge in Europe Today: The Honest Broker for the Week of February 1, 2015

The Rebalancing Challenge###

J. Bradford DeLong :: U.C. Berkeley

OëNB Conference on European Economic Integration :: Vienna :: November 24-25, 2014

There is an important purpose of an opening keynote talk like this one. Its task is to start from first principles and then give a large-scale bird's-eye overview to what is to come. We have panels to come on monetary policy, balance-sheet adjustment and growth, inequality and its role in generating internal macroeconomic imbalances, external macroeconomic rebalancing, and banking sector regulation. They all presuppose that Europe, and within it the regions of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe that we focus on here, need not just higher aggregate demand in the short-term but more. They need large-scale sectoral rebalancing. And that sectoral rebalancing needs to be rapid. Why? Because these economies will not grow smoothly without deep structural reforms--in these reforms need to be not just at the bottom but at the top, reforms of institutions, governance structures, and regulatory practices and mandates need to be carried out as well.

Note that the need, while urgent in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Southeastern Europe, is not by any means more urgent here then in the other regions of Europe.

Note that the need, while urgent in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Southeastern Europe, is not by any means more urgent here then in the other regions of Europe.

So why is more than higher aggregate demand right now what is needed? And which of the many things that go under the labels of "rebalancing" and "structural adjustment" are most needed? And why?

If in the next half-hour I can answer these questions convincingly then there will be an intellectual framework into which the rest of the conference's pieces will fit naturally, and we will all go back to our day jobs with a firmer grasp of the rebalancing challenge in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe.

Thus let me try to place the rest of today in its proper perspectives.

The first perspective to take is the very long-run perspective.

Let me note three dates: September 12, 1683; June 18, 1815; and November 19, 1942.

September 12, 1683 was, of course, the end of the Turkish imperial project. It was the date of the last truly mass slaughter right here. On that day the defending armies commanded by Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, reinforced by the relieving forces of King John III Sobieski of Poland, defeated and forced the retreat down the Danube Valley of the armies commanded by Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha.1 That was the last time that this segment, at least, of the Danube Valley saw the chaos, destruction, and death of large-scale long-lasting war. If von Starhemberg and Mustafa Pasha could see Southeastern Europe now, while they might mourn the loss of power of the dynasties they served, they would both be very pleased at the state of the people who live her--and both be very grateful that the peoples and states are, for the most part, not still locked in what looked then like an eternal region-encompassing destructive war of intolerant, militant faiths.

June 18, 1815 was, of course, the end of the French revolutonary-imperial project with the final defeat at Waterloo in Belgium of the army of the French Emperor Napoleon I Bonaparte by British, Dutch, and German forces under the command of the Irish-born Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. We all do owe a great deal to the implementation and then transmission of the good ideals of the Enlightenment by the French Revolution. We owe less than zero to the habit of deadly ideological purges introduced by the Convention in Paris and in the Vendee. And the practice of introducing and maintaining those ideals by every four years having a French army come through, burning as it went and living off the land, leaving famine in its wake, is something we can live without.2 If either Metternich or Talleyrand could see right now that we are now longer engaged in the military destruction of the struggle for French dominance over Europe that consumed the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries and that seemed to them to be perpetual, they would be pleased.

And November 19, 1942 was, of course, the end of the Nazi imperial project with the initial breakthrough of the Soviet Union's Red Army at Stalingrad on the Volga.3 It was followed by two-and-a-half more years of fire, blood, and death, and then a process of reconstruction that hang in the balance in Western Europe for a decade and is still not complete in Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, if those whose job it was to start rebuilding in 1945, if the Adenauers and de Gaulles could see us now, they would be very pleased. Right now the European project is a success. And we could not have said that on September 12, 1683; on June 18, 1815; or on November 19, 1942.

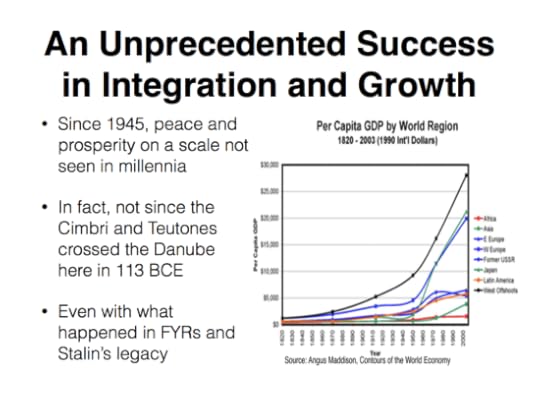

In fact, we can take a much longer perspective in which the post-World War II project of European community, unification, and peace has been a success. It was not far from here that the tribes of the Kimbri and the Teutones who had left their previous homes somewhere in or near Jutland crossed the Danube River into Noricum in 113 BC.

Was it 111 BC that the Kimbri and the Teutones, having moved down from Jutland to what is now Austria and crossed the Danube, decided they would rather cross the Rhine into the land of feta and olives in the Rhone Valley rather than eat Sauerkraut and sausage--or, back then, probably auroch jerky--in Noricum, near what is now Salzburg? So they went. And so they looted, burned, ravaged, killed, and ruled until a decade later they were broken at the battles of Aquae Sextiae and Vercellae by the new-model Roman Republican army commanded by Gaius Marius C. f. seven times consul.4 Ever since then, by my count, it is every thirty-seven years that a hostile army crosses the Rhine going one way or the other bringing fire and sword. The original Swiss--the Helvetii. Julius Caesar. All of those who claimed to be Julius Caesar's adoptive descendants. The Visigoths heading for Andalusia. Louis XIV commanding his armies to make sure that nothing grows in the Rhinish Palatinate so that his armies attacking Holland have a secure right flank. And, last, Remagen bridge in 1945. Every thirty-seven years, with increasing destructiveness as time passes.

Thirty-seven years after 1945 carries us to 1982. Thirty-seven years after 1982 will carry us to 2019. By 2019 we will have missed two of our appointments with slaughter. Even with Stalin's legacy, the difficulties of post-Cold War transition, everything that has happened in the republics of the Former Yugoslavia, and the current struggle over austerity and adjustment between the northern and southern pieces of the Eurozone, things have gone very well indeed recently.

Yet, I believe, most think that we desperately need political union in Europe as insurance to keep the bad old days from 111 BC to 1945 from coming again. We do not want Europe to once again fall victim to the tragedy of great power politics5. That means that politicians find some way to union--so that differences are thrashed out in conference rooms in Brussels and Strasbourg rather than in the streets with Molotov cocktails, submachine guns, armed drones, and worse. That is the necessity.

This does not mean that we should minimize Europe's current problems, just note that the problems are not as large as the achievements. The problems facing us are many. A very quick list consists of five. There are two major political problems:

Incorporating ex-superpowers into the common European home--a problem Europe has faced over and over again since 1600, first with Spain, then with France after 1815, then with Germany after 1870, and now with Great Russia.

Building institutions for continental governance in our late-Westphalian nationalist age.

And there are three major economic problems and opportunities:

Grasping rather than letting drop the enormous fruits of continent-scale economic integration that nearly all studies of economies of scale and economic integration say are there.

Accelerating the painfully and disappointingly slow convergence of both east and south to northwest European standards. Looking at the Asian Pacific Rim reveals that if we can get the institutions, the trade patterns, and integration more than half-right we can look forward to a régime of convergence in which living standards and productivity levels in a region converge halfway to the standards of that region's core in a generation. We can do it. We have done it elsewhere in the past. We should be doing it now in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. And, frustratingly, we are not: it is more the slow-boring-of-hard-boards than it is the thirty-glorious-years.

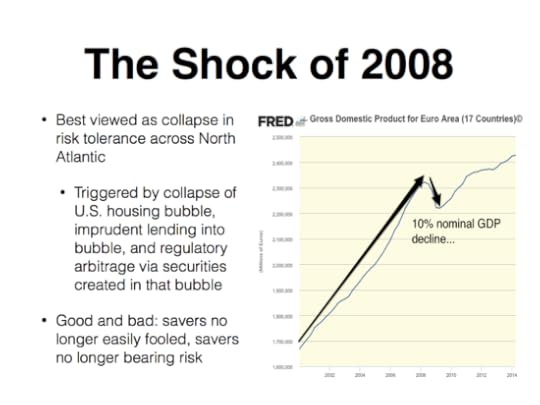

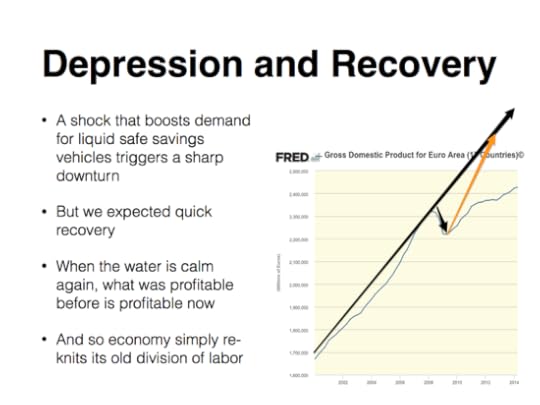

Successfully resolving and recovering from the shock of 2008 and its aftereffects. This is, mostly, what concerns us today. The other four problems are, mostly, in the background right now.

And the need is to do all of this in a global context that is not terribly supportive.

The global context of 2008 is a world that was characterized either by a global savings glut6 or a global investment shortfall, depending on which blade of the scissors is your favorite to focus on. That imbalance in turn produced either what one might call a global overleveraging: the gap between desired global savings at global full employment and planned global investment at global full employment was filled-in by credit creation to create funding for long-term investment projects that was not backed by savings commitments to long-run patient capital.7 One might, alternatively, call it a global shortage of risk tolerance: the gap between desired global savings at global full employment and planned global investment at global full employment was filled-in by promising savers that they were not bearing large amounts of systemic business-cycle risk when they in fact were.8 These are alternative ways of labeling the same underlying economic failure of expectations to be consistent that focus on somewhat different things--the apocryphal tale of the five wise men and the elephant comes to mind.9

We had a world in which there was no global hegemon, in a Keynes-Kindleberger sense, in Washington, willing to take responsibility for managing the level of global aggregate demand, even if the consequences for the domestic United States were potentially unfortunate.10 If in the 1950s and 1960s the U.S. under Bretton Woods had made a durable commitment to serve as the world's importer of last resort, its falling into the same role during what some called Bretton Woods II was contingent and evanescent.11

Moreover, we had a world in which there was no alternative local continental-scale orchestra-conductor focused on balancing effective demand to potential supply over the European continent as a whole. Instead, there were many countries, some of them very large, most of them focused inward, none of them thinking that responsibility needed to be taken. That, it was thought, ws the business of the European Central Bank, which had the proper monetarist tools to do the job of managing continent-wide demand. But what if those tools proved insufficient? The ECB did not have the power, and nobody had the power to do banking regulatory or fiscal policy in Europe on the proper continent-wide scale.12

Plus there was little sense in the years before 2008 of what a North Atlantic-wide Keynes-Kindleberger international economic hegemon would actually do. Such are used to dealing with problems of excessive aggregate demand, de-anchoring inflation expectations, and upward price spirals on the one hand; or with problems of liquidity shortage on the other. But we did not have a liquidity shortage--certainly not after the start of 2009. The monetarist playbook for how the Great Depression ought to have been handled was taken down from the shelf, dusted off, and applied.13 As a result the North Atlantic economy floated on an absolute sea of liquidity from the start of 2009 to the present day: so much has there been not-a-shortage-of-cash that central bank deposit velocity has fallen to low levels that I, at least, never thought I would ever see.

We have, instead, since the middle of 2008 had another kind of deficiency in the macroeconomy: aggregate demand has fallen below potential supply because there has been an excess demand for and a shortage of safe assets in the North Atlantic economy. That has been a consequence of an excess of risky assets, of an excess of nonperforming loans, of the transformation of assets formerly seen as safe into risky status. These problems are more sophisticated and less tractable to monetary interventions. Open-market operations that simply swap one interest-paying, or potentially interest-paying government liability with duration for a non-interest paying government liability with zero duration have next to no effect on the supply-and-demand for safe assets as a class.17

All this came to an end in 2008.

Now, in order to properly rebalance--even though rebalancing has been ongoing for six years--peripheral workers in Europe must either boost their productivity in making tradable goods or find something safe to do, must find something that does not require the mobilization of any substantial amount of European core risk tolerance in order to make the financing work, or must accept large real wages declines. These are the options. If it were not for the existence of the eurozone, all or nearly all peripheral European economies would choose the third: real wage reduction via depreciation of the currency. But for many that is not an option, or not a good option, or not seen right now as the best of the bad options. Peripheral depreciation for countries not in the eurozone and peripheral internal deflation for countries that are may in the end be the road chosen, in spite of all the economic pain and chaos it is generating now and will generate in the future. Euro-core inflation--"structural adjustment" in the northern core rather than in the periphery--is another possibility. Real "structural reforms" that successfully and substantially boost productivity in making tradable goods would be an option, if that unicorn could be found.

The problem is that "structural reform" too often stands as a placeholder for all good things that would increase an economy's productivity. The danger is that when commitments to "structural reform" are not accompanied by any political economy strategy to successfully disrupt the current stakeholders blocking reforms in order to confiscate their current rents.

Attempting to restore financial-market risk tolerance--but, we hope, not to go-go levels--is another possible strategy. A 7%/year gap between the returns to properly-diversified real European equity baskets and the returns to lending money to the German government could be greatly lessened without, in my judgment, running any risk of a new round of bubble finance. There is using the governments' powers to tax to mobilize the risk-bearing capacity of Europeans continent-wide--but if taxpayers are bearing the risk they deserve the returns of enterprise as well, and history had not been kind to those who think that governments' interventions in industry can take the form of a very large and high-return investment portfolio. Better, probably, for the government to boost the supply of safe assets via deferring the taxation to ultimately amortize expenditures it ought to be undertaking anyway than to involve governments on a larger scale as venture capitalists and industrial financiers.

This would be the case even were there not the additional problem that the risk-bearing capacity of taxpayers is mostly in the core of Europe, while the need for additional demand right now is mostly on the periphery. In the United States we do not track economic flows between states as Europe tracks flows between nations. We do not assign our national debt to individual states. We do not have to worry about this. In the United States back in 1991-2 after the collapse of the Savings and Loan bubble the United States central government transferred to Texas a sum equal to 25% of a year's Texas GDP--an amazing no-strings bailout--without there being any complaint or worry about fiscal transfers or about encouraging a feckless culture of moral hazard in rattlesnake country. Part of it was that we did not notice. Part of it was that the senior senator from Texas was in the key position of being Chair of the Senate Finance Committee. Europe cannot do the equivalent, or anything close, without political upset.

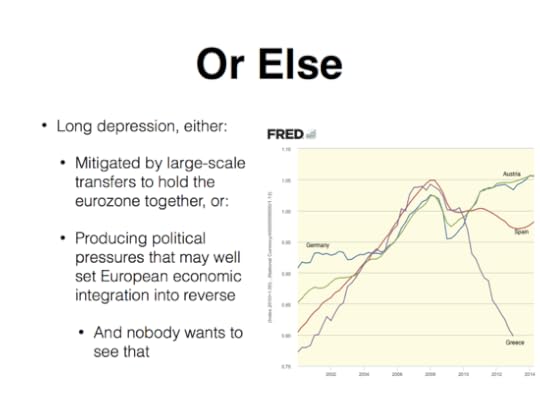

Or else?

If structural reform and demand management are not both successfully performed, the alternative for Europe is then a long and uneven depression. Such might produce political pressures to set European economic integration into reverse. That, however, is a low-probability scenario. The higher-probability scenario in the event of the failure of structural reform and demand management is for European union and the euro to be held together by, year after year, just enough fiscal transfers and debt relief from the core to keep the grinding pain of deflation in the euro periphery from becoming so great as to trigger reversal. This would, in the end, be a much more expensive strategy for the core's than taxpayers than one of biting the bullet and immediate resolution and debt writedown.

What can we say about the roads toward structural adjustment--toward an economic configuration that could sustain continent-wide full employment without relying on unreasonable expectations of risk and return?

For some countries, exchange rate policy is possible. Exchange-rate policy is very effective medicine. It is a very good way of improving competitiveness and sharing social burdens. The problem is that it is such only as long as inflation expectations are anchored in domestic nominal terms. When they are not--especially when inflation expectations become anchored to inflation in import prices--relying on exchange rate depreciation is worse than useless. It is a medicine that is effective until resistance develops, and the fear is that alongside resistance there will also develop addiction to this mechanism. Hence it should be resorted to gingerly, lest overuse lead to high inflation and to even more intractable structural problems.

Nevertheless, if the largest global financial shock in a century is not a time to resort to it for those countries that can, when would the proper time to resort to it be?

But how can we know whether tolerance has developed? That is a question. I do not have an answer.

Within the eurozone, internal devaluation is not a possibility. External devaluation--chiefly vis-a-vis the dollar, hoping that the United States will once again be willing to take on the role of importer of last resort--is a possibility. However, it does not resolve Europe's internal structural problems. What it does do is make life very pleasant for the export powerhouse that is Germany. And while life is pleasant for Germany, perhaps its politicians can be induced to make concessions and provide funding and take policy steps that do resolve Europe's internal structural problems.

There is the possibility of replacing the missing private risk-tolerance for large-scale loan guarantees, asset purchases, or public spending to create demand for products that enterprises in peripheral regions can produce. That requires that European politicians know and understand and be willing to use the debt capacity of Europe's core for the benefit of primarily the periphery but of the eurozone as a whole. There is "structural reform", and the knotty question of whether structural reform is harder when unemployment is high or when it is low. Those in Frankfurt and Berlin are sure that structural reform can be accomplished only when unemployment is high and politicians feel a sense of crisis in their bones. Those in Washington are sure that structural reform can be accomplished only when unemployment is low and politicians can assemble fleshpots of resources to be distributed to assemble majority political coalitions. I avoid taking a stand on this issue by saying that I am just an economist. I do, however, note that the fact that at most one of these can be true does not mean that at least one of these is true.

And, as noted above, inflation in the European core and deflation in the European periphery round out the list. We have not had much of the first. We have had a lot of the second. A 2%/year inflation rate for the eurozone as a whole with a 0%/year inflation rate in the eurozone's poorer half does mean 4%/year inflation in the eurozone's richer half. I do not see how anything good could come out of a monetary target that turns into a mandate that inflation in the European core must always be less than 2%/year. Whether all who staff the ECB fully understand this is not clear.

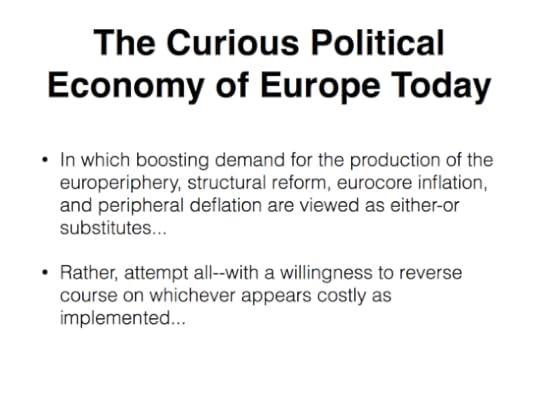

But among all these possibilities, why choose? These all seem to me to be not substitutes but complements.

Yet the political economy of today in Europe seems curious: these are all, overwhelming, posed as either-or substitutes, as mutually-exclusive alternatives. And I hear the same thing in the United States as well. Yet I have never understood this. I have always thought that the best and obvious strategy is to attempt them all--and to be willing to, pragmatically, reverse course on those that appear to turn out to have implementation costs greater than their potential benefits.

I have been waiting for five years for somebody to tell me why what seems obvious and best to me is not obvious and best.

And I am still waiting.

5720 words

Liveblogging World War II: January 29, 1945: Red Army Encircles Breslau

World War II Today: 29 January 1944: Bitter struggle as Red Army encircles Breslau:

The tide of war had turned decisively against the Germans and they faced defeat after defeat, retreat after retreat. For the captured German soldier, especially if they belonged to the SS, the fate was in many cases even worse. Some accounts refer to them being ‘given a beating’ but others are more explicit. One female Red Army soldier recalled that any captured German soldiers:

were not shot dead – that would have been too easy for them, we stabbed them like pigs with spears, chopped them to pieces. I saw it with my own eyes. I waited for the moment when their eyes bulged with pain.

She felt no mercy ‘They burned my mother and my young sister at the stake in the middle of the village’.

German soldiers were under few illusions about their potential fate and many saved the last bullet for themselves. Others made desperate attempts to escape to the west. Paul Arnhold was a Pioneer officer who had been on the run after his Panzer Corps had fallen apart. With three others he crossed Poland on foot, much of the journey across country, trying to evade the pursuing Russians.

Late in January they found a remote peasant hut and forced the elderly Polish occupants to supply them with food. At first they were offered potato stew but they suspected something better was available. They threatened the old couple until bread and salted meat were produced:

We could not contain ourselves and attacked it like wild animals. We paid the price for doing so; a short time later we brought it all back up again. Our weak stomachs could not cope with something like that any more.

The cottage gave them a brief opportunity to rest – but they were in poor state:

We carefully removed our boots and shoes, What was left of our socks and foot-cloths had gone hard from dried blood and pus. My soles were just pus-filled flesh, but the worst pain came from inside. As I’d been running for three weeks on soles which were bumed and warped, my metatarsal was horribly inflamed. When I stood up, the pain coming from it was unbearable.

In addition, my ankles had swollen badly where the top edge of my boots rubbed with every step. Our feet were a pathetic sight. In normal times, no one would have believed it possible that we could run even one more step.

Three weeks by day and night in snow and ice, hungry and hunted like wild animals. None of us had washed or shaved for three weeks. We had not changed our clothes for three weeks. We had worn our uniforms for three weeks.

During the ‘bathe’ in the Pilica they had been soaked. Then they had frozen solid in the icy storm, and then we’d been hunted and harried in our wet gear.

We huffed and puffed for three long weeks through undergrowth covered in snow and over vast expanses of snow. The uniforms were torn a thousand times by the brittle frozen branches and thorns. Ten days after our swim in the Pilica, our clothes were still damp.

My beard, with its many silvery-grey streaks, had grown so thick that my hands could reach into it.

We’d not been able to wipe our arses for three weeks. But what’s the use of telling this to someone who hasn’t experienced it? That little scrap of Pravda was more important for our [Russian] Machorka cigarettes than a civilisation which wouldn’t have suited us anyway.

For three weeks we’d been living like creatures in the jungle, ready to kill anyone who stood in the way of our progress, and ready to kill anyone who refused to give us food. Our mindset had become so primitive that we could no longer think of anything other than food and getting to the Oder.

There were only three of us left now. Never did we want to raise our hands in the air! Never! If we’d fired the last round and thrown the last hand-grenade, then we would have smashed the enemy’s face in with our bare rifles!

These accounts appear in Richard Hargreaves: HITLER’S FINAL FORTRESS – BRESLAU 1945. Hargreaves has used many original German and Soviet accounts, few of which are available in English, to tell the story of the savage fight for the capital of Silesia, the city of Breslau which Hitler had now declared to be ‘Fortress Breslau’. It would be defended ‘to the last man’ in a battle that would continue through to the end of the war.

Morning Must-Read: Daniel Davies: Rules for Contrarians: 1. Don’t Whine. That Is All

Apropos of Jonathan Chait's "Not a Very P.C. Thing to Say" and Hanna Rosin's "The Patriarchy Is Dead", some constructive advice from Daniel Davies:

Daniel Davies: Rules for Contrarians: 1. Don’t whine. That is all: "I like to think that I know a little bit about contrarianism...

...So I’m disturbed to see that people who are making roughly infinity more money than me out of the practice aren’t sticking to the unwritten rules of the game.... The whole idea of contrarianism is that you’re... setting out to annoy people.... If annoying people is what you’re trying to do, then you can hardly complain when annoying people is what you actually do. If you start a fight, you can hardly be surprised that you’re in a fight. It’s the definition of passive-aggression and really quite unseemly, to set out to provoke people, and then when they react passionately and defensively, to criticise them for not holding to your standards of a calm and rational debate. If [Levitt and Dubner's] Superfreakonomics wanted a calm and rational debate, this chapter would have been called something like: ‘Geoengineering: Issues in Relative Cost Estimation of SO2 Shielding’ [rather than the book being subtitled 'Global Cooling'], and the book would have sold about five copies....

The other point of contrarianism is that, if it’s well done, you assemble a whole load of points which are individually uncontroversial (or at least, solidly substantiated) and put them together to support a conclusion which is surprising and counterintuitive.... Because of this, if you’re writing a contrarian piece properly, you ought to be well aware of what point it looks like you’re making, because the entire point is to make a defensible argument which strongly resembles a controversial one. So having done this intentionally, you don’t get to complain that people have ‘misinterpreted’ your piece by taking you to be saying exactly what you carefully constructed the argument to look like you were saying.... A degree of diffidence is appropriate here, because the confusion is entirely and intentionally your fault: '(That is the ‘global cooling’ in our subtitle. If someone interprets our brief mention of the global-cooling scare of the 1970’s as an assertion of ‘a scientific consensus that the planet was cooling,’ that feels like a willful misreading.)' No it doesn’t; it feels like someone read the first two pages for the plain meaning of the words and didn’t spot that you were actually playing a little crossword-puzzle game... ‘global cooling’ meant, it was put on the cover in full knowledge of the impression it would give... so... it is not legitimate to complain that this phrase was interpreted in the way in which it was intended to be interpreted. In general, contrarians ought to have thick skins, because their entire raison d’etre is the giving of intellectual offence to others. So don’t whine, for heaven’s sake. Own your bullshit...

Belle Waring on Jonathan Chait: Political Correctness Gone Mad OMG I’m Scared: Live from La Farine

It is a true fact that Jon Chait's extremely ill-advised New York Magazine article crossed my desk at the same moment that I was watching this equally ill-advised piece by Meg Perrett and Rodrigo Kazuo go by. They try to condemn an eight-person classical moral-philosopher reading list for various sins against leftism1. The interesting thing is that they get no traction whatsoever, even though they are here at the University of California Berkeley at what Jonathan Chait imagines to be the hotbed of American crazy leftism.

Belle Waring administers the smackdown:

Belle Waring: Jonathan Chait: Political Correctness Gone Mad OMG I’m Scared: "By now you’ve probably heard that Jonathan Chait has written an article for New York Magazine....

Chait has about 75% of perhaps two points, but the wheat/arsenic-laced chaff ratio is bad. Very bad.... There is some element of pulling rank in questions about privilege.... [In] campus culture.... Chait cites examples of straight-up vandalism in which people’s signs were torn from their hands b/c they expressed the wrong views. This, plus the dude in the opening para, merits one full argumentative point....

[But] Jonathan Chait’s whining about “Political Correctness gone mad,” or, as I like to call it:

people criticizing me forcefully, in such a way as to call my liberal bona fides into question, and pretty much just calling me racist, when actually I was only adjacent to racists, and people should look into these things more carefully before they say something that might hurt someone’s feelings.

The shutting down last year of the storied magazine The New Republic, aka “The Even The Liberal.” When the magazine folded, Jonathan Chait wanted everyone to dab at their eyes with folded, clean linen handkerchiefs and mourn the death of A Higher Journalistic Calling. Instead, many writers reminded people... Marty Peretz more or less called... Palestinians... animals and savages.... The Bell Curve... how then-editor Andrew Sullivan pushed that to the forefront of American political discourse... and then claimed that the vigorous debate... was retroactive justification for the choice, and proved... Murray was one of the most prominent social scientists of his day, rather than the racist loon he was?... So Chait didn’t get the glorious send-off he wanted. He got a lot of fully deserved hits coming his way. So what lesson has he learned from this? That people should stop saying mean things about him on Twitter....

98% of what people angrily claim is “Political Correctness” is just manners. Politeness. If something I were saying at a dinner party offended another guest and my host explained why, I would stop saying that thing, in all likelihood. I myself used to call things “retarded” all the time when I was a kid.... I will occasionally call something retarded.... It’s not an appropriate thing to say; will you please correct me when I do it?... Does it make me angry because the word “cisgender” exists now? No, because I’m not an asshole.... Is this killing me? No....

Re-reading I see I haven’t addressed like 12 other weaksauce points, such as that outrage farming is a moneymaker (that’s why everyone’s always hiring queer disabled minority men to… wait, WTF?)

And also the complaining about trigger warnings AAAAAGH. Just don’t read Shakesville, no one’s making you!.... I, personally, have wanted and needed trigger warnings.... At times... I have wanted John to tell me in advance about a book, whether there’s rape in it or not, and then I won’t read it right then. My home did not suddenly become a den of feminist groupthink in which John was forbidden to speak...

The list of authors not containing women, People of Color, or (supposedly) LGBTQ* representatives, but instead being composed of white males from the five imperial powers of France, Germany, Italy, America, and England--never mind that the authors don't seem to know that Michel Foucault did not come from America; that Plato and Aristotle did not come from Italy; that Aristotle at least half came from the city of Atarneus, in what is now Turkey, hardly an imperialist power; that Plato, Aristotle, and Foucault would today be coded as LGBTQ*; etc. It may all be a joke.

January 28, 2015

Noted for Your Nighttime Procrastination for January 28, 2015

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Project Syndicate: What Failed in 2008?

The Macroeconomic Situation and Macroeconomic Policy: Insiders and Outsiders: Focus

Macroeconomics: Listening to Reality: A Note from Twitter I Want to Save

Tim Duy: While We Wait For Yet Another FOMC Statement

Nick Bunker: The federal budget, interest rates, and savings gluts

Plus:

Things to Read at Nighttime on January 22, 2015

Must- and Shall-Reads:

Loren Adler: What the CBO Budget Outlook says about the ACA

Phillip Rucker: "If he runs again in 2016, Romney is determined to re-brand himself as authentic..." <--Greatest line ever!

Alan Beattie: Greece: the case against ‘structural reform’

Yanis Varoufakis: Finance Ministry slows blogging down but ends it not

William Cohan: "These gifts to Wall Street came without a requirement that it change any of the most fundamental aspects of the way it does business..."

Martin Wolf: "Creditors have a moral responsibility to lend wisely. If they fail to do due diligence on their borrowers, they deserve what is going to happen. In the case of Greece, the scale of the external deficits, in particular, were obvious. So, too, was the way the Greek state was run..."

Christopher Neely: "The strong market reactions to the Federal Reserve’s suggestion that it would taper its asset purchases are consistent with the similarly strong reactions—in the opposite direction—to unexpected Federal Reserve asset purchase announcements. The lesson from the taper tantrum is that the QE programs have had the desired effect on asset prices, suggesting that the purchases have influenced output, employment, and inflation expectations in the desired direction."

Glenn Greenwald: "I fundamentally agree with Jill Filipovic’s reaction: ‘There is a good and thoughtful piece to be written about language policing & ‘PC’ culture online and in academia. [Jonathan Chait's] was not it...’"

Steven J. Davis and Till von Wachter (2011): Recessions and the Costs of Job Loss

Tim Duy: While We Wait For Yet Another FOMC Statement

And Over Here:

Hoisted from the Archives: Special David Gelernter and Michael Kinsley Feel-Bad Piece of the Month of July 2005

On the Fed's Policy of Quantitative Easing Coupled with Promises Not to Let Prices Recover Any of the Ground Relative to Trend They Lost in the Recession: Hoisted from the Archives from Three Years Ago

What Failed in 2008? by J. Bradford DeLong - Project Syndicate

Over at Equitable Growth: The Macroeconomic Situation and Macroeconomic Policy: Insiders and Outsiders

Macroeconomics: Listening to Reality: A Note from Twitter I Want to Save

Liveblogging the American Revolution: January 28, 1777: John Burgoyne

Steven J. Davis and Till von Wachter (2011): Recessions and the Costs of Job Loss: "We develop new evidence on the cumulative earnings losses associated with job displacement, drawing on longitudinal Social Security records from 1974 to 2008. In present-value terms, men lose an average of 1.4 years of predisplacement earnings if displaced in mass-layoff events that occur when the national unemployment rate is below 6 percent. They lose a staggering 2.8 years of predisplacement earnings if displaced when the unemployment rate exceeds 8 percent. These results reflect discounting at a 5 percent annual rate over 20 years after displacement. We also document large cyclical movements in the incidence of job loss and job displacement and present evidence on how worker anxieties about job loss, wage cuts, and job opportunities respond to contemporaneous economic conditions. Finally, we confront leading models of unemployment fluctuations with evidence on the present-value earnings losses associated with job displacement. The model of Mortensen and Pissarides (1994), extended to include search on the job, gener- ates present-value losses only one-fourth as large as observed losses. More- over, present-value losses in the model vary little with aggregate conditions at the time of displacement, unlike the pattern in the data."

Tim Duy: While We Wait For Yet Another FOMC Statement: "The Fed recognizes that hiking rates prematurely to 'give them room' in the next recession is of course self-defeating. They are not going to invite a recession simply to prove they have the tools to deal with another recession. The reasons the Fed wants to normalize policy are, I fear, a bit more mundane: (1) They believe the economy is approaching a more normal environment with solid GDP growth and near-NAIRU unemployment. They do not believe such an environment is consistent with zero rates. (2) They believe that monetary policy operates with long and variable lags. Consequently, they need to act before inflation hits 2% if they do not want to overshoot their target. And they in fact have no intention of overshooting their target. (3) They do not believe in the secular stagnation story. They do not believe that the estimate of the neutral Fed Funds rate should be revised sharply downward. Hence 25bp, or 50bp, or even 100bp still represents loose monetary policy by their definition. I am currently of the opinion that there is a reasonable chance the Fed is wrong on the third point, and that they have less room to maneuver than they believe."

Should Be Aware of:

Gary Legum: Ron Paul Escapes Tethers In Son’s Basement, Heads To Fun Secession Conference For Fun

Kenneth Vogel: "Since the tea party burst onto the political landscape in 2009, the conservative movement has been plagued by an explosion of PACs that... exist mostly to pad the pockets of the consultants who run them... plow most of their cash back into payments to consulting firms for additional fundraising efforts..."

Dietz Vollrath: Techno-Neutrality

Joe Romm: The Climate Science Behind New England's Historic Blizzard

Jim VandeHei and Jonathan Martin (2011): "We love Palin. And if Palin does not exactly love us... she knows how to exploit our weakness to guarantee herself exposure far out of proportion to her actual influence in Republican politics... mutual dependency and mutual enabling.... Palin is great at the box office.... Should we really be giving so much attention to somebody who faces so many hurdles to becoming president or even the GOP nominee?... Why... is she covered so intensely?... The Palin obsession says as much about the modern media as it does about the state of American politics right now: We just can’t quit her.... She’s a draw. The left loves to mock her, the right rushes to defend her and folks in between seem to be fascinated by the whole spectacle.... We know we’re part of the problem--and we’ll surely continue to run stories about Palin.... Yes, she’s good copy, and yes she’s good for business. But that doesn’t mean she should be treated as a president in waiting."

2009: Berkeley Political Economy 100: Reference Document DRAFT

2009: Berkeley Political Economy 101: Reference Document DRAFT

Jamelle Bouie: The Imaginary 'Moynihan Report': "it’s absolutely true that Moynihan wanted to strengthen the black family... he saw this as a core duty of the federal government, a stance at odds with both Christie and Lewis: 'The policy of the United States is to bring the Negro American to full and equal sharing in the responsibilities and rewards of citizenship... shall be designed to have the effect, directly or indirectly, of enhancing the stability and resources of the Negro American family.'... Moynihan was absolutely clear-eyed about the reasons for the weakness of the black family.... Pace Lewis, he didn’t blame ‘the welfare state,’ he blamed racism: 'The Negro situation is commonly perceived by whites in terms of the visible manifestation of discrimination and poverty, in part because Negro protest is directed against such obstacles, and in part, no doubt, because these are facts which involve the actions and attitudes of the white community as well. It is more difficult, however, for whites to perceive the effect that three centuries of exploitation have had on the fabric of Negro society itself. Here the consequences of the historic injustices done to Negro Americans are silent and hidden from view'.... Welfare dependency, in Moynihan’s view, wasn’t a given—the inevitable result of giving unearned aid to able people. Welfare dependency, he argued, was a direct consequence of family disintegration, which—in turn—was a direct consequence of America’s brutal treatment of African Americans..."

Freddie de Boer: The Condescending Neoliberal Dicknose Is Right! To a Degree: "I got something cooking, but let me just say this in this space: privilege theory itself, which is used endlessly by the people that Chait is critiquing, explains why Chait is correct to a degree. (Only to a degree.) And it's in this sense: there is a large number of very vocal people online who have no personal stake in social justice whatsoever who, in the way that they argue for social justice, actually make political progress less likely. I know this annoys people; I know it aligns me with a lot of noxious assholes. But there really are people who are broadly associated with the left who seek outrage for outrages sake. There really are. These people are white, but constantly speak for people of color; they're affluent, but speak for the poor. They hate oppression but don't suffer from it. So they have no skin the game. They don't care if the way they engage actually contributes to a more just world. They don't care if their engagement is politically constructive or destructive. They don't care if they are building a political coalition that could win. All they want is to earn this weird social credit that we've developed, where you get social and cultural capital for being the person who pronounces something offensive. They are more interested in calling things problematic than in solving problems. (Some of them appear very regularly in this very commenting space.) What could be a bigger indication of privilege than not caring whether your political movement actually can win? And so as much as Chait is a condescending neoliberal dicknose--and I have gotten into more fights with him than I can count--the left has to actually acknowledge that there is a problem, here. The left has to acknowledge that there are people who speak in the name of the left who are actively hurting the cause of social justice. It's easy for us to talk shit about Chait, and I have and I will continue to. But there is a no-bullshit, honest-to-god problem with today's left, and telling jokes on Twitter won't solve it."

Links:

Jim VandeHei and Jonathan Martin (2011): "We love Palin..." http://dyn.politico.com/printstory.cfm?uuid=C1F5F8DC-18FE-70B2-A81430A8C754FA08

Joe Romm: The Climate Science Behind New England's Historic Blizzard http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2015/01/26/3615330/blizzards-climate-scientists

Dietz Vollrath: cite>[Techno-Neutrality https://growthecon.wordpress.com/2015/01/26/techno-neutrality

Phillip Rucker: "If he runs again in 2016, Romney is determined to re-brand himself as authentic..." http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/romney-ahead-of-2016-run-now-calls-utah-home-talks-openly-about-mormon-influence/2015/01/27/c3875940-a4ef-11e4-a06b-9df2002b86a0_story.html <--Greatest line ever!

Yanis Varoufakis: Finance Ministry slows blogging down but ends it not http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/01/27/finance-ministry-slows-blogging-down-but-ends-it-not

Christopher Neely: "The strong market reactions to the Federal Reserve’s suggestion that it would taper its asset purchases are consistent with the similarly strong reactions—in the opposite direction—to unexpected Federal Reserve asset purchase announcements. The lesson from the taper tantrum is that the QE programs have had the desired effect on asset prices, suggesting that the purchases have influenced output, employment, and inflation expectations in the desired direction." http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/es/article/10036

Tim Duy: While We Wait For Yet Another FOMC Statement http://economistsview.typepad.com/timduy/2015/01/while-we-wait-for-yet-another-fomc-statement.html

Loren Adler: What the CBO Budget Outlook says about the ACA https://storify.com/onceuponA/what-the-cbo-budget-outlook-says-about-the-aca

Martin Wolf: "Creditors have a moral responsibility to lend wisely. If they fail to do due diligence on their borrowers, they deserve what is going to happen. In the case of Greece, the scale of the external deficits, in particular, were obvious. So, too, was the way the Greek state was run..." http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/44c56806-a556-11e4-ad35-00144feab7de.html

Freddie de Boer: The Condescending Neoliberal Dicknose Is Right! To a Degree http://gawker.com/i-got-something-cooking-but-let-me-just-say-this-in-th-1682128509

Alan Beattie: Greece: the case against ‘structural reform’ http://blogs.ft.com/the-world/2015/01/the-greek-economy-the-case-against-structural-reform/

Jamelle Bouie: The Imaginary 'Moynihan Report' http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/03/14/the-imaginary-moynihan-report.html

William Cohan: "These gifts to Wall Street came without a requirement that it change any of the most fundamental aspects of the way it does business..." http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/01/wall-street-rises-again/383514

Steven J. Davis and Till von Wachter (2011): Recessions and the Costs of Job Loss http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/steven.davis/pdf/RecessionsCostsJobLoss.pdf

Gary Legum: Ron Paul Escapes Tethers In Son’s Basement, Heads To Fun Secession Conference For Fun http://wonkette.com/574042/ron-paul-escapes-tethers-in-sons-basement-heads-to-fun-secession-conference-for-fun

Kenneth Vogel: "Since the tea party burst onto the political landscape in 2009, the conservative movement has been plagued by an explosion of PACs that... exist mostly to pad the pockets of the consultants who run them... plow most of their cash back into payments to consulting firms for additional fundraising efforts..." http://www.politico.com/story/2015/01/super-pac-scams-114581_full.html

2009: Berkeley Political Economy 101: Reference Document DRAFT http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2009/06/berkeley-political-economy-101-reference-document-second-draft.html

2009: Berkeley Political Economy 100: Reference Document DRAFT http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2009/05/berkeley-political-economy-100-reference-document-draft.html

Hoisted from the Archives: Special David Gelernter and Michael Kinsley Feel-Bad Piece of the Month of July 2005

The feel-bad piece from the month of July 2005 is, of course, David Gelernter and his editor Michael Kinsley, beating out--mirabile visu!--even the works of Donald Luskin.

Here's the quote from David Gelernter, the thing that Michael Kinsley thought worth spending the Los Angeles Times's space on back in July of 2005. I put it below the fold. Don't look at it unless you are willing to be triggered:

David Gelernter:

You might argue that dark-skinned people are a special case, given the way the United States has treated them. I agree--we have treated them so solicitously, and worked so hard to suppress racial prejudice, that dark-skinned people owe their country the benefit of the doubt...

An Open Letter to Michael Kinsley

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2005/07/an_open_letter_.html

2005-07-30

On the Fed's Policy of Quantitative Easing Coupled with Promises Not to Let Prices Recover Any of the Ground Relative to Trend They Lost in the Recession: Hoisted from the Archives from Three Years Ago

Hoisted from the Archives: The conventional Fisher-Friedman approach to the determination of nominal spending and income focuses on the equilibrium demand and supply of money through the quantity theory:

(1) PY = MV(i)

If the economy’s money-supply process has produced “too little” money for the current level of spending, businesses and households attempt to shift their portfolios and accumulate more money by (i) trying to sell some of their other financial assets for cash, and (ii) cutting back on their spending. Thus the flow of spending—and income, and production—falls until PY has fallen by enough to make households and businesses no longer seek to increase their money holdings. Combine this focus on money supply and money demand equilibrium with some model of price theory and price adjustment, and the result is a theory of the monetary business cycle.

At the zero-interest rate lower nominal bound, this Fisher-Friedman framework breaks down. With no opportunity cost to holding wealth in money rather than in other short-duration safe nominal assets, there is no reason for changes in the money stock to induce any changes in the flow of spending at all. Anybody seeking to model nominal and real income determination must then find another, alternative equilibrium condition to focus on.

The conventional theoretical macroeconomic step to take is to focus on the intertemporal Euler equation of a representative household with rational expectations: is it on an optimal consumption-savings path? But focusing on the Euler equation requires that there be (a) no disagreements between investors, and (b) a meaningful representative household, with (c ) correct rational expectations. If we are unwilling to make those assumptions, we are then driven back to the equilibrium condition from which, given the existence of no disagreements, a representative household, and rational expectations, the Euler equation was derived.

This equilibrium condition--appropriate for a more general theory—-is the Wicksell-Hicks flow-of-funds through financial markets condition: the supply of savings vehicles must be equal to the demand for savings vehicles. If the demand for savings vehicles is greater than the supply, people will cut back on spending their savings on currently-produced goods and services as they try to boost their holdings of savings vehicles. Spending, production, and incomes will fall until people feel so poor that they no longer wish to boost their holdings of savings vehicles. When the supply of savings vehicles is greater than demand, people will increase their spending as they try to turn their excess asset holdings into current consumption. Spending, production, and incomes will rise until the richer society is happy holding the existing supply of savings vehicles.

Thus theories about the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of any kind of policy—monetary, fiscal, banking, whatever—at the zero nominal interest rate lower bound are ways of deploying Wicksell-Hicks flow-of-funds equilibrium condition. They are theories about:

(2) B + S = B + I + (G - T)

about the demand for savings vehicles—the sum of the current stock of financial assets in the economy B and desired additions to that stock through savings S—and the supply of savings vehicles—the sum of the current supply of financial assets B plus business investment I plus government debt issuance G - T.

Note that if you wish to assume a (a) representative agent with (b) rational expectations you are still committed to an analysis via (2). It is a consequence of your intertemporal Euler equation. If and only if (2) holds, then your representative agent with rational expectations is on its optimal consumption-savings path.

Equation (2) gives us insight into the potential effectiveness of monetary policy at the zero lower bound. Such non-fiscal policies do not, by definition, change the supply of savings vehicles: they simply swap one savings vehicle in private portfolios for another—cash for Treasuries, short Treasuries for GSEs, private obligations subject to bankruptcy risk for private obligations backstopped by a government guarantee. For them to boost the economy therefore, they too must work via their effects on reducing private savings S or boosting private investment I.

How can they do this?

Mostly, they do this by convincing financiers that the path of real interest rates will be lower in the future than they had expected. Even though at the zero nominal lower bound the current size of the money stock is irrelevant because the opportunity cost of holding money is zero, this will not always be the case. Someday the size of the money stock will matter again. And if the central bank now takes steps that credibly promise such a larger money stock in the future when it matters, then expectations of lower nominal interest rates and higher price levels in the future which should boost investment and other real interest-sensitive components of spending now.

What are these policies?

Jawboning to reduce anticipated real interest rates: The central bank can claim that it will maintain interest rates in the future at a lower level and the money stock at a higher level than that of its normal policy reaction function. Thus, the central bank would claim, inflation will be higher in the future than forecasts based on normal reaction functions would allow. That means that real interest rates will be lower—and that would push down savings and push up investment.

The potential difficulty is that open-market operations can be unwound. That the Federal Reserve has raised the money stock this year does not necessarily mean that it will keep the money stock five years hence above the level called for by its standard reaction function. Pure jawboning is the ultimate in cheap talk. Jawboning backed by quantitative easing at the short end of the term structure is not quite pure cheap talk: the central bank is taking action. The problem is that the action is easily reversible.

Quantitative easing at the short end to reduce anticipated real interest rates: The central bank can claim that it will maintain interest rates in the future at a lower level and the money stock at a higher level than that of its normal policy reaction function—and back up those claims by expanding the money stock now by continuing to buy short-term government bonds for cash even though this is simply a swap of one zero-yielding short term safe nominal asset for another. The idea is that the Federal Reserve is not just claiming it will expand the money stock in the future—it has already expanded the money stock.

The potential difficulty is that open-market operations can be unwound. That the Federal Reserve has raised the money stock this year does not necessarily mean that it will keep the money stock five years hence above the level called for by its standard reaction function. Pure jawboning is the ultimate in cheap talk. Jawboning backed by quantitative easing at the short end of the term structure is not quite pure cheap talk: the central bank is taking action. The problem is that the action is easily reversible.

Quantitative easing at the long end to reduce anticipated real interest rates: The central bank can claim that it will maintain interest rates in the future at a lower level and the money stock at a higher level than that of its normal policy reaction function—and back up those claims by expanding the money stock now by to buying long-term government, agency, and private bonds for cash and committing to holding them to maturity. The idea is that the Federal Reserve is not just claiming it will expand the money stock in the future—it has already expanded the money stock. And such transactions are not or at least are not as easily unwound. Price pressure effects mean that the Federal Reserve will, embarrassingly, probably lose money on the round trip if it breaks its commitment to hold its purchased securities to maturity.

Quantitative easing at the long end may have another significant effect as well. By taking duration and, in the case of private bonds, default risk onto its balance sheet the Federal Reserve transfers that risk from the marginal investor to the marginal taxpayer. If the marginal taxpayer is at a corner solution in their financial market holdings or has a higher rate of time discount than the marginal investor or simply does not see through the government’s balance sheet, one consequence of quantitative easing at the long end is that investors will then have unused risk-bearing capacity. Duration and default risk spreads should then fall, and this fall in spreads should turn more investment projects into positive NPV ones. Quantitative easing at the long end thus has not only its potential principle effect on private investment and other forms of interest-sensitive spending via expectations of inflation and thus of real safe interest rates but also a secondary effect on investment via the government’s assumption of a role as a risk-bearing partner in private enterprise.

Back-of-the-envelope calculations based on standard finance principles suggest that this portfolio-composition effect should be insignificantly small. But similar arguments based on standard finance principles have long suggested that standard open-market operations in normal times should not be able to shake the intertemporal price system out for thirty years either, and there is a lot of evidence that standard open market operations in normal times do in fact have substantial effects.

Quantitative easing accompanied by declarations that the central bank has not changed its long-run inflation and price level targets: I do not understand why a central ban would pursue such a policy.

But that is the policy that the Federal Reserve appears to have decided to pursue.

Ryan Avent:

Monetary policy: The Fed's communications problem: As I've written before, the commitment to allow higher inflation in the future is one of the key methods through which the central bank can have a positive effect on an economy stuck at the zero lower bound. The Fed's efforts to clarify and push out the date at which it is likely to raise rates strikes me as a means to try and commit itself to higher inflation in the future. But the Fed's communications efforts in this regard run up against a serious obstacle in the form of the Fed's long-term inflation forecast, which is 2%. The Fed can't force future central banks to keep to any policy path. If the Fed were to project a long-run inflation rate above 2% then, as Mr Bini Smaghi says, markets might suppose that monetary tightening lay ahead, whatever the fine print says.

This is not an unsolvable problem but is, I think, one of the tight spots in which the Fed finds itself as it transitions from a framework that wasn't very good at boosting the economy at the ZLB to one that might be. One way to get around the problem would be to change the target, to 3% inflation or to something else, like a price or nominal GDP level, that implies future inflation above currently acceptable levels. The Fed may get there eventually, but probably not soon enough to have a meaningful impact on this recovery.

An alternative might be to bring the point at which future inflation is tolerated a bit closer to the present. That is, the Fed doesn't necessarily run into problems of inconsistency if it projects inflation above 2% 1 or 2 years from now—a timeframe over which markets readily understand this group of policymakers to have control—while maintaining the long-run 2% goal. Achieving that would require the Fed to give itself a framework within which it's acceptable to have inflation above 2% (and even to try to generate inflation above 2%), and as I wrote last week, I thought the Fed took a big step in that direction at its latest meeting. But one then has to choose to act within that framework. I suspect that what that will take is a near-term projection of inflation above 2% combined with action—asset purchases—designed to demonstrate that, yes, the Fed is actually trying to create a little catch-up inflation. At the last press conference, Ben Bernanke all but admitted that that would be a sensible thing to do. Now we just need to excise the "all but".

2025 words

What Failed in 2008? by J. Bradford DeLong - Project Syndicate

Over at Project Syndicate: For a while the best book on the macroeconomic catastrophe that struck the North Atlantic starting in 2007 was Gary Gorton's Slapped by the Invisible Hand. Them for a while the best book was Alan Blinder's After the Music Stopped. Now these have been superseded by two: the extremely-observant sensible Tory Martin Wolf's The Shifts and the Shocks; and my friend, patron, teacher, and (until the last reshuffle) office neighbor Barry Eichengreen 's Hall of Mirrors. Read and grasp the messages of both of these, and you are in the top 0.001% of the world in terms of understanding what has happened to us--and what the likely scenarios are for what comes next.

Consider, first, Martin Wolf's The Shifts and the Shocks. Its spine is a masterful cataloguing of all the major shifts we have seen that set the stage for the disaster that hit the North Atlantic in 2007-9:

The huge rise in the wealth of the global 0.01% and 0.1%, with its consequent pressures for overleverage and demand volatility

The global savings glut, with more of the same pressures.

The "insouciance" toward the resulting risks generated by the intellectual victory of the rational-expectations and efficient-markets hypotheses.

The resulting deregulation, that made it easy to sell assets perceived to be safe that were not in fact so and to greatly multiply the systemic risk in the system beyond any central banker's imagining.

The resulting policy-making climate, with the three-fold hubris of: (1) underestimating tail risks, (2) settling on a 2%/year inflation target that did not provide sufficient systemic risk sea-room, and (3) the greater hubris of the creation of the euro.

The continuation in which it apparently made sense in 2008 and since to do what was necessary but no more than necessary to handle the immediate crisis

In the context of these shifts, Martin Wolf sees immediate need in the short-run for policies to solve the immediate crisis: more spending, especially investment spending, by reserve-currency issuing sovereigns; more issue of high-quality debt to resolve the safe asset shortage by reserve-currency issuing sovereigns; and reserve-currency issuing central banks that monetize enough of this debt to raise the trend inflation rate from 2%/year to 3%/year or 4%/year. The argument seems, to me at least, to be convincing and unassailable.

But that is not all. Wolf's book calls as well for medium run policies: (1) Either "break up... or... create a minimum set of institutions and policies" to make the euro work. And (2) the obvious but undone regulatory measures to greatly diminish leverage and the use of debt. And last come Wolf's recommendations for the long-run: policies for more equal wealth; better economics less in thrall to rational-expectations and efficient-market ideologues; "more global regulation... and more freedom for individual countries to craft their own responses". These seem to me to be obvious requirements on the situation.

But 2005-2014 did not create the pressures to do what Wolf and I see as the obvious things. Why not? And here is where Eichengreen's Hall of Mirrors is most useful.

It tells the story of a historical process with dicw stages. The first is the intellectual victory within sensible economics of monetarist over old Keynesian and Minskyite interpretations of the Great Depression. The second is the resulting ability and willingness of governments to pull the monetarist policy package--what Milton Friedman had promised would have stopped the Great Depression in its tracks and erased its effects--off of the shelf and apply it in 2008-2009. The third is the very incomplete but also very real partial effectiveness of that package, for the monetarist interpretation of the Great Depression was, to put it baldy, wrong and radically incomplete. But it did enough good that a full-fledged repetition of the Great Depression was avoided.

And that led to the fourth stage: the declaration by governments of victory--of green shoots--of the successful resolution of a crisis--of a need to turn policies toward more important "structural" issues involving the necessity for "austerity" in the size of government. This fourth stage has been followed by the sixth in which we are now embedded: First, a very partial barely-a-recovery, one that is turning into a new normal in which the North Atlantic will turn out to have thrown away a full ten percent of all of what was its potential future wealth. Second, the failure to undertake the financial regulatory and economic governance reforms needed to diminish the chances of a repeat of the disaster in which we are still embedded.

Thus, Eichengreen concludes, partial success turns out to be global failure: immediate pain of a proportional magnitude equal to that of the Great Depression was avoided, but the potential for economic growth and successful macroeconomic stabilization in the North Atlantic going forward will be (because of failure to learn the lessons of 2000-2010 and make the obvious reforms) less post-2015 than it was post-1945, back when the lessons of 1925-1935 had been learned and the obvious reforms had been made.

Wolf sets out what we ought to have done. Eichengreen provides the narrative of the historical process which has led us not to do it.

889 words

Over at Equitable Growth: The Macroeconomic Situation and Macroeconomic Policy: Insiders and Outsiders

Somebody Is Inside an Echo Chamber. But Who?

Paul Krugman fears that somebody is trapped inside an echo chamber, hearing only things that confirm what they already believe:

Disagreement... over US monetary policy... [between those] very worried that the Fed may be gearing up to raise rates too soon... [and the] sanguine... seems to depend on one thing: whether the economist in question is currently in a policy position.... We don’t have access to different facts; we don’t, in any fundamental sense, have different economic models...

But how can we tell which side has lost contact with the reality out there?

Well, I think--as does Paul--that it is the "insiders" who are being optimistic and unrealistic in their plans to start raising short-term safe interest rates from zero in June 2015 and then, if past tightenings are any guide, raise them to what they regard as a full-employment growth-along-the-potential-path level of 5%/year or so by the end of 2017. READ MOAR

One reason is that I do not see a strong world and a weak dollar that would produce a stronger export boom relative to potential, do not see a recovery of relative government purchases to normal levels, cannot envision much stronger business investment without support from other strong components of demand, cannot see the restructuring of housing market finance that would produce even a normal pace of housing construction, cannot see where else durable demand expansion could come from, and fear adverse shocks.

But I do not think we have to decide. I think that even if we are uncertain whether the optimistic "insiders" or the pessimistic "outsiders" are correct, elementary prudent optimal-control theory tells us that we should act as if the "outsiders" are right.

But I have gotten ahead of myself:

Tim Duy says:

Tim Duy: Policy Divergence: "The Federal Reserve stands...

...in stark contrast with its... counterparts.... The ECB... quantitative easing, the Bank of England... more dovish... Denmark joined the Swiss in cutting rates... the Bank of Canada.... How long can the Fed continue to stand against this tide?... The Fed should of course be cautious.... But how does the Fed communicate such caution?

The challenge I see for the Fed is that they will want to hold the statement fairly steady.... Such a steady hand, however, may be viewed as hawkish, which is also a message the Fed does not want to send.... Bullard wants to ignore the market-based inflation metrics that would have in the past told him to hold off on any tightening. He really, really wants to liftoff from the zero bound, the sooner the better. I don't think this level of immediacy is felt by other FOMC members, but I do think they are hoping and praying the data gives them enough to move by mid-year...

And:

Tim Duy: While We Wait For Yet Another FOMC Statement: "The Fed recognizes that hiking rates prematurely...

...to 'give them room' in the next recession is of course self-defeating. They are not going to invite a recession simply to prove they have the tools to deal with another recession. The reasons the Fed wants to normalize policy are, I fear, a bit more mundane: (1) They believe the economy is approaching a more normal environment with solid GDP growth and near-NAIRU unemployment. They do not believe such an environment is consistent with zero rates. (2) They believe that monetary policy operates with long and variable lags. Consequently, they need to act before inflation hits 2% if they do not want to overshoot their target. And they in fact have no intention of overshooting their target. (3) They do not believe in the secular stagnation story. They do not believe that the estimate of the neutral Fed Funds rate should be revised sharply downward. Hence 25bp, or 50bp, or even 100bp still represents loose monetary policy by their definition. I am currently of the opinion that there is a reasonable chance the Fed is wrong on the third point, and that they have less room to maneuver than they believe.

Paul Krugman says:

Paul Krugman: Insiders, Outsiders, and U.S. Monetary Policy: "even smart, flexible people can fall prey...

...to incestuous amplification.... I worry that this is what is happening to the insiders. On the whole, it seems less likely for the outsiders, although it’s true that the Keynesian econoblogs form what amounts to a tight ongoing discussion group that could be doing some amplification of its own...

And:

Unusually, Olivier [Blanchard] and I... have a... disagreement... over US monetary policy.... I’m very worried that the Fed may be gearing up to raise rates too soon; he’s sanguine... part of a wider split... [that] seems to depend on one thing: whether the economist in question is currently in a policy position. Larry [Summers]... sounds exactly like me:

Deflation and secular stagnation are the threats of our time. The risks are enormously asymmetric.... The Fed should not be fighting against inflation until it sees the whites of its eyes....

We don’t have access to different facts; we don’t, in any fundamental sense, have different economic models.... If you ask me, there’s a worrying complacency among the insiders right now, and I would urge them to consider the potential consequences...

So how would we tell whether, right now, it is the outsiders are overstating the dangers to premature tightening, or it is the insiders who are understating the dangers to premature tightening here in the United States?

To answer this question, I think we need to consider five points--the first about our decision procedure, the second about the level of spending consistent with full employment, the third about the degree of uncertainty and variability, the fourth about the vulnerabilities of the economy to spending deviations above and below the projected current-policy path, and the fifth about the effectiveness of our optimal-control levers in different scenarios.

The first point is that if it turns out that we cannot tell--that we have to split the difference--then the considerations that rule are the asymmetries in the situation.

The second point is that no one right now has a good and convincing read on what, exactly, the level of spending consistent with full employment at the currently-projected price level is. Uncertainty is rife: if there was ever a time for considering not just the central tendency of the forecast but the risks on either side and taking optimal control appropriately valuing these risks seriously, it is right now.

The third point is that we are not just uncertain about what the proper full-employment path for demand is, we have much more than the usual amount of uncertainty about nearly all other dimensions of the structure of the economy. To suppose that any of the emergent properties that are policy multipliers can be estimated from data collected during "normal" times is to make an enormous leap of faith.

The fourth point is that downside risks to the forecast greatly exceed upside opportunities. The inflation rate is so low that marginal deviations from the target on the upside have little cost. The employment-to-population ratio is so low that marginal deviations of it on the downside from its projected current-policy path are very costly.

And the fifth point is that, while the Federal Reserve has powerful levers to restrict demand if spending shoots above the desired policy path, its levers to expand demand if spending falls below have been demonstrated over the past six years to be relatively weak.

Thus, if it turns out that we cannot tell--and we cannot tell--then it is not correct that we should split the difference. The considerations that rule are then the asymmetries in the situation. It is, right now, much worse to undershoot than to overshoot full-employment demand: the one causes extra and pointless unemployment, the second disappoints the rentier, and we live in a poor world in which the first is more of a policy error than the second. It is, right now, true that entral banks have a very easy time restricting aggregate demand via contractionary policy but--at and near the zero lower bound, at least--a hell of a time boosting aggregate demand via expansionary policy.

These asymmetries mean that, as far as policy is concerned, the "outsiders" win any tie and win any near-tie: the "insiders" should govern what policy should be only if there is not just a preponderance of the but clear and convincing evidence on their side.

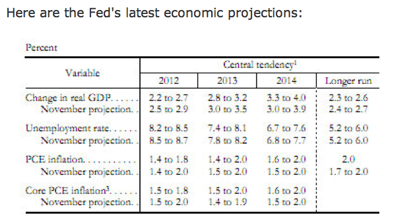

Yet the Federal Reserve appears to have decided:

that those who think that the economy is near full employment and is in a durable recovery have by far the better of the argument as to what the central tendency projected current-policy demand path is.

that it is appropriate to make policy via certainty-equivalance.

Given the inability of the Federal Reserve to attain traction at the ZLB, its current frame of mind--which appears to be doing certainty-equivalence policy--makes no sense to me. Certainty-equivalence is appropriate only with a symmetric loss function and a symmetric ability to compensate for deviations on either side of the target. We do not have either of those.

Has there been an explanation of why the Federal Reserve's policy is appropriate, given the uncertainties, given the asymmetry of the loss function, and given the asymmetry of the control levers, that I have missed? If so, where is it?

1644 words

Macroeconomics: Listening to Reality: A Note from Twitter I Want to Save

.@MikePMoffatt: Things like this have raised and greatly sharpened my estimate of current ZLB fiscal multiplier: http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2015/01/over-at-equitable-growth-yes-the-past-four-years-are-powerful-evidence-for-the-keynesian-view-of-what-happens-at-the-zero-l.html

Since 2007, reality has spoken.

Since 2007, reality has raised my estimate of the U.S. fiscal multiplier from 1.5 to 2.5, and sharpened it. Since 2007, reality has raised my estimate of the U.S. debt capacity from 75% of a year’s GDP to >150%. Since 2007, reality has left my very fuzzy estimate that the effects of QE are small unchanged.

Now Scott Sumner says 2013-14 a huge surprise that should have shifted my estimates again, substantially. And I really do not see why...

.@cellsatwork: There’s an extended substantive pre-response [by Krugman to Sumner]:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/01/06/the-record-of-austerit

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/01/07/professors-politicians-and-moments-of-truth

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/01/21/euroblunders

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/01/22/how-super-was-mario-wonkish.

Sumner doesn't seem to have read any of it...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers