Fernando Gros's Blog, page 15

October 1, 2020

Personal Blogging In 2020

Right now a thing called blogtober is trending. More than in any recent year, there seems to be a flourishing of bloggers trying to post regularly.

It’s probably a consequence of 2020. We’ve been forced to think about what our lives mean. We’ve spent a lot of time alone. We’re frustrated by the limitations of our social connections. And we’ve decided we have a story to tell.

Personal Blogs In Times Of Crisis

Blogging originally flourished in a crisis. Blogging’s best years were the post-9/11 years. There was a crisis of confidence around the reporting of the second Iraq war. More specific crises, such as rapidly falling sales in the music industry, or reaction to abusive leaders and entrenched power structures in the Christian church, also gave rise to large and growing communities of bloggers.

Authenticity, truth-telling, and the value of personal, lived experience were core features of these blogs.

They also flourished because they shared unvarnished vignettes of life that were often absent in regular news and journalism. You could see this in restaurant, TV, and film blogs that broke with the established conventions of review writing. And especially, with blogs that focused on domestic life, and parenting (like this piece I wrote in 2008).

Why Blogging Declined

Personal blogging kind of fell apart as monetisation took hold. A new authenticity market flourished, promising bloggers financial rewards through ad revenue, free stuff, and payment for promoting things, in exchange for being themselves. The collaborative culture started to fail. Bloggers with smaller audiences grew tired of going unnoticed. Bloggers with bigger audiences got more mainstream opportunities, writing books, or working for larger publications.

Many of my fellow bloggers, the authenticity rebels, are now blue ticks on Twitter.

Eventually social media swept everyone up by offering a better (or at least easier) way for people to communicate online. Writing a blog and maintaining a website was hard and costly. Social media was free and easy.

However, the market for authenticity never went away.

The Market For Authenticity

Authenticity fuelled the early growth of Twitter, but that was when it was a more optimistic, tech-focused space. Later, the explosion of YouTube, thanks in large part to personal vlogs and video essays, met the need. The “ordinary person trying something” ethos of YouTube was in many ways the manifestation of blogging’s original promise.

Thanks to this, the market for authenticity has flourished. But it’s mostly been a visual flourishing, led by YouTube and followed up by Instagram (and lately TikTok). Twitter isn’t what it used to be. Of course, blogs are still around, though the growth in written expressions of authenticity seems increasingly to be in newsletters.

Beyond these forms of media there’s also the plethora of courses and learning opportunities that offer you the chance to discover yourself, be yourself, fulfil your personal ambitions, and tell your story.

I was wrong back in 2012 when I predicted the comeback of personal blogs. I was wrong because I expected the resurgence of authenticity to be literary, but it turned out to be visual. What took off was YouTube and Instagram rather than blogs and new blogging platforms. When words returned it was more spoken, through podcasts and audiobooks, than written with blogs.

But I repeat: the market for authenticity has never gone away. Now we find ourselves in another crisis. We’re hungry for new voices, and many established channels for published writing are shrinking.

I find myself feeling similar to how I did back in 2012, though less certain and more circumspect about making big predictions.

I’m going to enjoy this resurgence in blogging for as long as it lasts. I’m not sure what form will draw the most attention in the future. But I still believe the market for authenticity is vast; there has never been a more important time for all of us to invest in it.

As I said back in 2012,

“… any time life hands you the opportunity to be sucessful by being yourself, it is a beautiful thing.”

The post Personal Blogging In 2020 appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 30, 2020

Neo-Monasticism

I wake up at the same time. Every day. Usually a few minutes before the alarm goes off. I pick my morning attire from a selection of nearly identical indigo-coloured cotton jinbei (Japanese pyjamas). Breakfast is a bowl of granola, yogurt and berries, followed by some sort of home-cured meat, smoked salmon or bacon, with homemade bread. I eat this in silence while reading. Usually something inspiring about living well and having good habits. After writing for an hour or so, it’s time for coffee, made every time according to the same precise ritual and carefully measured combination of ground beans and hot water.

This is how I’ve lived for more than six months now. Here in London. During this pandemic. Call it quarantine, isolation, lockdown, or shelter in place.

I call it neo-monasticism.

The Trend Of Neo-Monasticism

The morning routine above is tinged with aesthetic hipsterism. It isn’t meant to be. But it’s not hard to imagine it being turned into a motivational YouTube video. There are so many methodical morning routine videos out there.

This is just part of a bigger trend in the productivity and self-help world, even in the fashion-oriented end of the influencer space.

Everyone is behaving increasingly like medieval monks.

We’re obsessed with habits and rituals. We don’t just write journals and self-reflections, capturing the ways we’re trying to be better people, but we decorate these journals in ornate ways. We embrace minimalism and minimise waste and emphasise the wholesomeness of what we consume. We treat our clothes like a uniform. We meditate to discipline our mind, and we exercise to discipline our bodies.

We’re focussed on being on the side of good in the world.

The Medieval Internet

Late last year, New York Magazine had a special feature with articles speculating on what life would be like in the coming decade. Amongst them was a piece by Max Read, entitled In 2029, the Internet Will Make Us Act Like Medieval Peasants.

Unlike the usual criticisms of internet culture, Read suggested that being online is fostering an enchanted, crypto-magical worldview, where behind every conversation lurks invisible, seemingly mystical forces.

“The internet doesn’t seem to be turning us into sophisticated cyborgs so much as crude medieval peasants entranced by an ever-present realm of spirits and captive to distant autocratic landlords.”

It’s not hard to see this at work in the surprisingly popular QAnon cult and other online conspiracies. IL2 But this feels like something bigger than what’s happening at the ends of society.

Technology’s Mystical Qualities

This hasn’t happened because we shun technology but because we embrace it. You could say the internet is our new religion, while apps and devices are the altars and churches. But there’s something deeper.

There’s a metaphysical quality to so much discourse today. Beliefs have replaced ideas. An abstract battle between good and evil stands in place of more substantial and nuanced moral reasoning. It’s not hard to imagine the warring hordes fighting it out on daily online battlefields as New Age virtual crusaders out to lay claim to their own slice of the holy land.

“Thanks to ubiquitous smartphones and cellular data, the internet has developed into a kind of supernatural layer set atop everyday life, an easily accessible realm of fearsome power, feverish visions, and apocalyptic spiritual battle.”

Waiting For The Reformation

The social order that included monks dominated European society for centuries before it came to an abrupt halt thanks to the Reformation. Depending on where you study the Reformation, it might be presented as a much-needed cleansing of church and society, or a needlessly brutal upheaval of a system that needed improvement.

But regardless, it feels impossible to justify the suffering, the people killed and tortured in order to purify society.

In a way it feels like we, the new monastics, are also waiting for change, for reform of our social order as well. We’re obsessing about habits and rituals and daily practices because we know so much of the way we’ve inherited doesn’t work.

We are right to want change. We’re also right to believe change will start with the way we live our lives down to the smallest details.

But we’ll need to think hard about the way today’s internet culture is changing the way we speak, and think, and treat the people around us. The way ideas travel from disembodied voices online into our own bodies, out of our mouths, and through our actions.

The post Neo-Monasticism appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 24, 2020

Attention Span

It’s a recurrent complaint – people’s attention spans are shrinking. Neil Postman wrote about it in the 1980s, suggesting that human attention had peaked at some point soon after the Enlightenment and was quickly fading, thanks to the corrosive effects of TV.

By the mid-2000s it had become conventional wisdom to blame the Internet for shortening our attention span. Since then the lure of social media has inspired stronger and stronger calls to consider the effect of the Internet on our attention, such as Ten Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, by Jaron Lanier, and Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport.

Curious to know what you might think about this, I ran a snap poll on Twitter. The results were stark. More than 80% of respondents felt their attention span was getting shorter.

Has your attention span decreased in recent years?

— Fernando Gros (@fernandogros) September 16, 2020

Understanding Attention Span

All these stories share a common understanding of what an attention span is. It’s a function of time. Our attention span is how long we can work on a task without our focus being lost to some distraction.

Span is a fascinating word, though. It’s used in numerous ways. Span can measure time, including the duration of our concentration, of course. Or how long we live. Span can also refer to distance: the length of a bridge, or the width of a plane’s wings.

Span can even be used to explain relationships. Take the term “span of influence”, used in business to describe how many people report, directly and indirectly, to a manager or leader in an organisation.

What if we try to consider all these uses of the word, to help understand how our attention span works? To do that we can borrow from a very old concept – the Quadrivium.

Attention In Time

The Quadrivium was a set of four subjects, which in medieval times formed the basis of study at the schools that would lead to what we now know as universities.

Inspired by the thinking of Pythagoras in ancient Greece, the Quadrivium took on their final form thanks to Boethius in sixth-century Rome. There are still echoes of the Quadrivium throughout liberal arts education today.

The Quadrivium was focused on the study of numbers. First was arithmetic, which is simply numbers, or quantities. Next was geometry: numbers in space, or quantities at rest. Music is numbers in time, or the relations between quantities. Finally there’s astronomy, which is numbers in time and space, or quantities that are inherently moving.

What the Quadrivium reminds me of is that in any act of measuring something we can consider other ways it could be measured. There’s often more than one way to think about relationships between a thing and that thing’s moment in time and space.

A concept like an attention span can be more than just a number in time. It’s also a relationship that exists in both time and space.

Attention In Space

So, if our common understanding of attention is a number in time (for example, how many seconds you can keep reading this article before checking your social media feed), then what might attention as a number in space mean?

Well, if this article is one amongst a sea of other open tabs in your browser, then that might be one way to look at it. Or perhaps it’s one e-mail in an inbox full of other ideas.

The number of things you try to give your attention to is just as important as how long you try to pay attention.

Attention Doesn’t Have To Be Infinite

When people suggest our attention span is getting shorter, blaming TV, the Internet, social media, or something else, it always begs the question – how long does our attention span need to be?

If you can’t read even one page of a book without reaching for your phone, then obviously there’s a problem. But must you be able to read the entire book at one sitting? At some point, wouldn’t it be natural for your attention to shift? Perhaps it’s time to go to the bathroom, or walk the dog, or feed yourself?

Attention is task-dependent. The bridge span must be wide enough to safely cross the river, the aeroplane’s wings wide enough to keep it in the air.

Your attention span must be wide enough and long enough. It need not be infinite.

“People who feel like they have enough time know how to linger in moments that deserve their attention; they can stretch the present when the present is worth being stretched”

– Laura Vanderkam

Attention – The Final Frontier

What we’re doing is moving away from the idea that attention is a fixed attribute, like liquid in a bottle, or a single muscle you can work out. Attention is how we react to the challenge of focussing or concentrating in a specific moment and in a given environment.

Attention is a system.

Our mind isn’t directly wired to the things we try to concentrate on. Attention happens (or it doesn’t) within a system. What’s happening inside your body is only one part of that system.

So going back to the question of whether or not our attention span is getting shorter, it might be better to reframe the question and ask: how has our attention system changed?

Growing Your Attention System

A 2017 study showed that just having your smartphone around, even if you’re not looking at it, can reduce your ability to pay attention.Having our smartphones with us all day can lead to a kind of mental weariness that hampers our decision-making and even our well-being.

Building our attention system necessitates taking control of the environment within which we want to pay attention. This starts with minimizing distraction.

Trying to concentrate in an environment full of devices screaming for our attention through notifications and red “message waiting” icons is a battle we cannot win. The distraction economy was already too big for us back when I wrote about it in 2010. It’s only grown bigger, smarter, and harder to beat since then. Your devices, and all the apps in them, are designed by smart people who are paid lots of money, to eat up your attention.

If you can’t pay attention to that book because you keep reaching for your phone, then put away your phone.

Engineering A Bigger Attention Span

Any system that works has been designed. Sometimes that design is beautiful and elegant. But it doesn’t have to be.

Designing a system requires choices. What is the problem? How can it be solved? And what steps are required to make solving the problem a reliable process?

The steps to improving our attention system require us to adopt a somewhat countercultural frame of mind. There are at least three choices to be made.

The Attention Mindset

First, we need to stop filling the silence. We must become comfortable once again with the ambiguity of not knowing what this moment means.

Humans developed the ability to pay attention as a way to decide what information matters from among a variety of sources. But if you pay attention only to a small set of sources of information (say, what appears on your screen), you’ll struggle to pay attention when faced with another source of information, such as a book.

The best way we can start to do this is to avoid the urge to fill silence, by which I mean a moment that seems empty of information, by reaching for a device like a phone or a computer screen, or a specific, highly stimulating app on either of those.

We struggle to accept silence because we’ve grown to fear boredom. We have to break down this resistance, maybe even welcoming boredom into our lives again as part of an ebb and flow of attention.

We so easily retreat to places in the distraction economy, such as social media, because there’s an almost guaranteed pay-off. Gazing at a tree for a few minutes might give us a glimpse of a bird or a squirrel, but a scroll through Instagram will give us a funny animal meme almost instantly.

But that’s not a given. It doesn’t have to be your default. And if you’re still reading this there’s a pretty good chance you don’t want it be.

Attention Span And Making Memories

I don’t hate memes, or social media, or screen entertainment. Often I enjoy them very much. But the odds I will remember that cat meme in a few years are close to zero. Conversely, I can vividly remember moments spent watching wildlife many years later.

This mindset shift, embracing the silence and empty moments, not fearing boredom, not going into some default mode that always looks for fun, does take some getting used to. It’s not the way most people are living now. But, then again, most people seem to be struggling with their attention span.

Once you make these kinds of adjustments, it will become easier for you to build an attention system that lets you concentrate, with more focus, for longer periods of time. Your attention span hasn’t gone. It’s waiting for you to give it space again.

The post Attention Span appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 17, 2020

How Friction Can Help

“Maybe we could jam soon.”

“Sure. Send me some charts and a tape of your music and we’ll work something out.”

“Ummm, OK.”

We often think the path to greater productivity involves removing barriers and obstacles. We aim for a frictionless life. But perhaps some friction is a good thing?

Friction Can Add Clarity

Ryder Carroll, creator of the Bullet Journal Method, was recently on the Focussed podcast discussing productivity. He described being in a new job where everyone was calling a lot of meetings. Many of the meetings felt like a waste of time. People were talking so they could figure out what they thought. A lot of the meetings ended with no clear set of actions.

So he instigated a plan. Before calling a meeting, co-workers had to write out its objectives and some guidelines for the decisions that had to be made.

The result was: people asked for fewer meetings.

This wasn’t Carroll’s goal, of course. He wanted better meetings. What happened was fewer meetings, and workers finding other ways to solve problems or figure out how they wanted to work.

A little friction made a huge difference.

Learning To Add Friction

Back when I was playing a lot of live music I’d often get asked to “jam”. This is musician-speak for turning up at a rehearsal space with no real plan, just to “see what happens.”

Jam sessions can be magical. But all too often they’re just like the kind of workplace meetings Ryder Carroll was trying to avoid. For every transcendent experience of improvised bliss there were scores of frustrating moments as people faced their creative and musical limitations.

Back then I barely had enough time as it was to play the gigs, teach the students I had, learn new material, and improve my own skills. This only got worse when I had a day job.

So I came up with a simple hack. Whenever someone got talking about their idea for a band, or a music project, and then asked me to jam, I would say “Sure” but also invite them to just send some charts and a recording of their music. I always promised to make time after that.

One of two things then happened. Most people never got back in touch. But the people who did had amazing ideas, and were fun to work with.

A little friction did a lot to lift the best opportunities out of the pile of requests.

Adding Friction To Maximise Efficiency

It’s tempting to focus always on the fastest and most convenient ways of doing things. But convenience and speed don’t always maximise efficiency.

Part of the reason why paper-based planning is so popular right now is the way it naturally slows you down. The methodical nature of writing down your notes and plans, the friction of pen on paper, helps focus the mind.

Planning on paper makes it evident when you are over-committing. You can feel the resistance as your to-do list grows too long. Using a Kanban to visualise your work has a similar effect.

Friction invites reflection. Slowing down creates the space for your productivity habits to become more mindful.

Adding Friction To Improve Social Media

Recently I’ve been using the Toikimeki app to go through the accounts I follow on Twitter. It’s a play on the Marie Kondo approach. The page shows you one account at a time and asks you if that person’s timeline still “sparks joy.”

It’s a slow process. Thankfully the app lets you stop and start and pick up later where you left off. It’s also deeply rewarding. You are reminded of cool people you’d forgotten about, either because the algorithm wasn’t sharing their thoughts with you or just because you weren’t online at the same times. And of course, it’s satisfying to unfollow accounts that are now sharing ideas you don’t want to amplify.

Friction Clarifies Purpose

Friction invites questions. Why this? Why now? Why me? When the answers are clear, the motivation rises to meet us. But if the answers are not clear the friction makes it easier to say no.

Adding a little friction to your processes does two things. It clarifies what effort must be put into doing something; how well prepared we and others are for the task. And it helps us decide whether to commit to doing it or not.

In a way, everything revolves around being good at knowing when to say yes and when to say no. Friction can be surprisingly helpful at making us better at doing just that.

The post How Friction Can Help appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 12, 2020

How To Create A Personal Kanban

It begins in Japan in the 1950s. The Toyota Motor Company is struggling. Its cars aren’t as good as those made in America, and its factories are less productive. Taiichi Ōno, an engineer, starts looking at the company’s processes. He finds a number of ways in which Toyota is wasteful and inefficient.

Taiichi devises a system using paper cards – Kanban, from the Japanese for sign board – that tracks products through the manufacturing process. Using Kanban makes Toyota more productive, reduces waste, and improves quality. Kanban are the backbone of a series of changes that go on to help Toyota grow throughout the ʼ60s and ʼ70s and eventually will influence approaches to manufacturing around the world.

By the 2000s, Kanban have made their way into software development. Developers in large companies like Microsoft start using them and, through blogposts and conference presentations, the use of Kanban becomes popular.

Kanban In Personal Productivity

In 2009, Jim Benson started to write about using Kanban approaches for personal productivity. Personal Kanban, which Benson co-wrote with Tonnianne DeMaria Barry, brings together these ideas.

Personal Kanban is a relatively short book. A hundred and eighty-six well-spaced pages. At times it’s a frustrating read. There are anecdotes that don’t go anywhere. The history of Kanban, or the vast literature that explores Kanban at a philosophical or academic level, is glossed over.

What Personal Kanban does well is explain how to build a Kanban system for the various tasks we face in our personal and working lives.

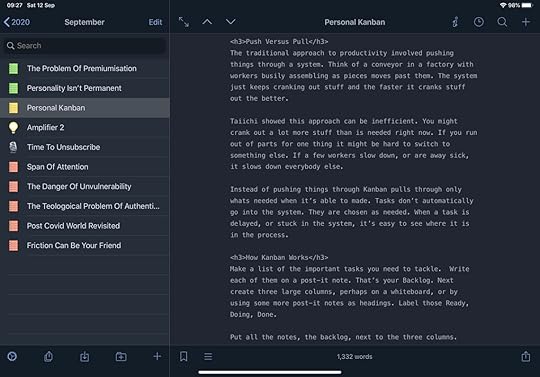

Push Versus Pull

The traditional approach to productivity involved pushing things through a system. Think of a conveyor in a factory with workers busily assembling as pieces move past them. The system just keeps cranking out stuff, and the faster it cranks stuff out the better.

Taiichi showed this approach can be inefficient. You might crank out a lot more stuff than is needed right now. If you run out of parts for one thing, it might be hard to switch to something else. If a few workers slow down or are away sick, it slows down everybody else.

Instead of pushing things through, Kanban pulls through only what’s needed when it’s able to be made. Tasks don’t automatically go into the system. They are chosen as needed. When a task is delayed or stuck in the system, it’s easy to see where it is in the process.

How Kanban Works

Make a list of the important tasks you need to tackle. Write each of them on a Post-it note. That’s your Backlog. Next, create three large columns, perhaps on a whiteboard, or by using some more Post-it notes as headings. Label those Ready, Doing, Done.

Put all the notes, the Backlog, next to the three columns. Next, pick some of the tasks – the ones that are your highest priority, and that you could do in your succulent situation with the resources available to you. Put those under Ready.

Next, pick a small number of tasks – maybe three, no more than five – you are going to start working on. Move those to Doing. That’s your work in progress.

Here’s the thing. Until you finish those, until they start going into the Done column, you can’t grab anything else from the Ready group. You must focus on the Doing items. As things move from Doing to Done you can replace them, one at a time, from the Ready group. As you start to empty the Ready group, you can add more items from the Backlog.

That’s your Kanban in action.

Personal Kanban and Notion

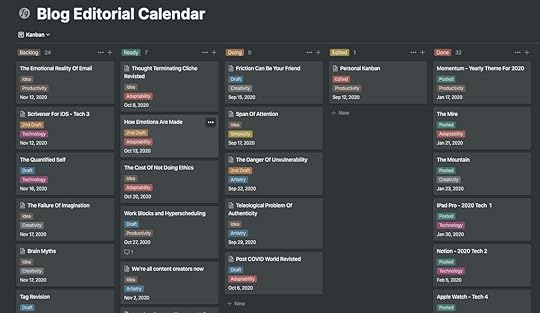

My current fascination with Kanban stems from finding them inside Notion. When you create a database in Notion, a number of standard views are available. These are familiar to anyone who uses productivity software. Table, List, and Calendar. There’s also Kanban.

Using Kanban for this blog’s editorial calendar helped me address a number of problems with my approach to writing.

There are always a lot of ideas in the system. Right now, there are enough potential articles for me to post once a week through until spring next year. But those ideas don’t all go from first draft to final edit at the same speed. The recent piece on premiumisation took a week from inspiration to going live. The one about having fewer beliefs was kicking around for more than a year.

When I sit down to write every morning, I don’t want to be scanning a long list of possible topics. Doing that just invites procrastination.

Using the Kanban view to limit work in progress helps me keep the focus down to four or five ideas. It makes that morning’s choice clearer.

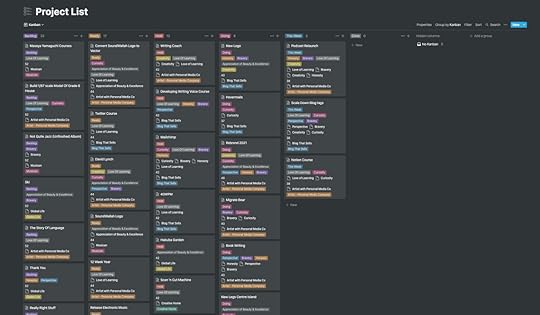

Expanding Your Personal Kanban

As you use your Kanban, you can add more stages to the basic Ready/Doing/Done schema. Personal Kanban suggests two useful additions: Pen and Today.

Pen is a holding place for projects that are waiting for something to arrive or someone to reply. During the delay, it makes sense to work on something else. In my editorial calendar this is replaced with a self-explanatory column called Edit.

Today is simply a column for the thing, or things, you want to work on today. For my editorial calendar this wasn’t necessary. But for the bigger list of personal projects, I adopted a This Week column, since I tend to look at my week as a whole, rather than changing focus day to day.

Using Kanban For Mindful Productivity

Visualising your work with Kanban helps you become mindful of your approach to productivity. You can see when projects get stuck. Using Kanban highlights any tendency to focus on things other than the tasks you’ve decided to focus on.

It invites reflection and personal innovation around the way you work.

You can customise your Kanban further depending on your insights – maybe using different colours to denote different kinds of projects or areas of interest, or adding more columns for other kinds of interruptions in your flow, like review stages – or some kind of priority hierarchy.

In my experience, though, keeping it simple, with as few layers as possible, heightens the benefits of limiting your work in progress and focussing on only a few projects at time.

Personal Kanban Productivity

What I love about Kanban is how platform-agnostic the system is. Right now I have Kanban in Notion. I could port that to some other software, or recreate it with Post-it notes on a wall or cards on a cork board.

Since it’s a way of visually representing your work rather than a total philosophy, you can use it alongside other productivity systems. It enhances my otherwise standard approach to editorial calendars, together with Getting Things Done and Build a Second Brain ideas in my other projects.

For me, the key insight from exploring Kanban has been limiting current work in progress.

Too often, I’m prone to swoop down on any shiny new distraction or idea. The disarmingly simple logic of Kanban is the best solution I’ve found to help me avoid that while still feeling like all the creative possibilities remain, waiting to be played with another day.

This is a strange time, with many of us still working from home and opportunities for collaboration and travel still limited. But the time will come when we can create and move more freely. Then, as opportunities blossom again, we’ll have to make hard choices about where to focus our energy. Kanban could help.

The post How To Create A Personal Kanban appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 7, 2020

The Problem With Premiumisation

‘We’d like you to submit five or six unpublished features on your favourite undiscovered locations in Japan. Please include a few photos for each article.’

What sounded like a freelancer’s dream offer was, once I read the fine print, something close to a scam. As I explained back in 2017, a high-profile magazine had asked me to submit a whole bunch of work for their consideration. Maybe they’d publish it; maybe they wouldn’t. Maybe I’d get paid; maybe they’d send a cheaper in-house writer to do the job instead.

This is just one of the challenges freelancers face today. On one side, you’re often working for free or expected to accept ‘exposure on social media’ in place of payment. On the other side, if you want to be paid well, the accessibility afforded by the internet means you’re often competing with the best in the business.

‘An increasing number of individuals in our economy are now competing with the rock stars of their sectors.’

– Cal Newport

The solution a lot of creatives aspire to is leaving freelancing for making. Instead of selling your time, you sell your products. It’s an idea expertly explained by Paul Jarvis in The Company of One, (which I discussed here).

If your work involves selling your time for money, then you soon hit a limit for how much you can earn. Even if you’re the best in the world, there’s a limit to how much time you can trade for money. If you’re not the best in the world, then you’re competing against free. There’s always someone willing to do it for less – or for nothing more than likes online.

And if you’re not working, you’re not making money.

You need to break the connection between the amount of time you work and the money you make.

Of course, making stuff isn’t easy. If you’re going to replace a freelancing income, you’ve still got a big hurdle to overcome. Broadly (and at the risk of making an either/or simplification), you have two choices: scale or premium.

Scale simply means you make a lot of things. Premium means you make fewer things but charge more.

Premiumisation is the ugly word we use for the process of trying to cultivate a premium business. You aim to make things that are better, unique, or perhaps limited in availability and grow an audience of people willing to pay a premium for them.

For me, releasing the limited edition version of my book was an eye-opener. There were the usual products – a paperback, a Kindle version – but then I also produced a $65 hardback version handmade by a Japanese printer. And it sold surprisingly well. I’ve also had a lot more success selling big, expensive prints of my photos than chasing scale by selling my images to stock libraries. So my focus shifted to premiumisation as well.

Premiumisation During A Pandemic

The premiumisation strategy has been effective for everything from boutique guitar pedals to handmade stationery for most of the last 20 or 30 years.

But with the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic now affecting so many people, premiumisation feels problematic.

The question of where to go with premiumisation has been on my mind all summer. From email exchanges and Zoom calls, I’ve discovered I’m not the only one wondering about this. Looking at my online store makes me wonder where to go from here. It’s even seeped into my writing, like when discussing the cost of things like the Building A Second Brain course.

The problem of premiumisation in an age of pandemics came up on The Pen Addict podcast. Brad Dowdy discussed a thoughtful update from the owners of Musubi, a premium stationery company. Musubi’s statement outlines three strategic pillars for addressing the challenge anybody in the business of premiumisation is now facing.

First, Musubi plans to focus on products that promote their consumers’ creativity and mental health. As they put it, ‘…many of our customers use their Musubi journals as part of their daily routine, whether to write, draw, or journal in, and we play an important role in helping people cope.’

This will mean paying even more attention to materials and design of the products to make them more joyful and satisfying to use.

Next, Musubi plans to cut FOMO (fear of missing out) from the marketing strategy. They’re getting rid of ‘special edition’ language, or anxiety-inducing processes like expecting consumers to log in at specific times, or within narrow opportunities, to place an order.

Finally, Musubi is going to explore ways to be more affordable, most likely through new products that can be offered at lower price points.

Healthy Commerce

This threefold strategy involves being positive, patient, and price-sensitive. It resonates deeply with how I’ve been feeling about adjusting my premiumisation model. Healthy consumers, healthy purchasing decisions, and a healthy market feels like the right response.

What Musubi isn’t doing is massively cutting the price of all their products. Rather, they are thinking deeply about the benefits they provide to their customers.

It does feel like the mix of kindness and commerce we need right now.

The post The Problem With Premiumisation appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 4, 2020

Personality Isn’t Permanent

I adore personality tests. I’ve written about them before. They can be fun. You can gain insights about yourself and understand why you react the way you do in various situations.

Of course, they’re not perfect. Too often these tests make wild generalisations. People use them like horoscopes to predict behaviour. This can be deeply unhelpful in relationships or workplaces.

Benjamin Hardy isn’t a fan of personality tests. He believes they perpetuate myths about personality that have been debunked by research. Personality tests encourage us to view personality as innate and fixed. But this isn’t so. Rather, our personality can evolve and be shaped by the choices we make.

Hardy suggests that instead of doing a test to discover the personality we’ve inherited, we should be setting goals that will create the personality we want.

Your Personality Is Who You Will Be In The Future

Most people describe their personality by looking back over their life. They draw a picture based on past decisions and events. And that picture is who they authentically understand themselves to be.

Hardy’s contention is that this approach is wrong, self-limiting and potentially harmful. It’s not the path to a fulfilled life.

We should have a clear sense of who we want to become, then behave in ways that align with those goals. For Hardy, being authentic means being true to the person you’re becoming, and not the person you were.

So if our personality can change, why is the idea that personality is fixed so popular?

The reason most people don’t change isn’t because personality is fixed. People don’t change because change isn’t a goal for them. They are in a rut because of trauma or limiting beliefs. Or they simply don’t have an appetite for change.

The meat of Personality Isn’t Permanent is the way it addresses four reasons why people’s personalities stop evolving.

Personality And Trauma

Trauma is a negative experience that shapes your self-identity in limiting ways. Trauma is the most challenging reason why people’s personalities get stuck.

Hardy tells the story of someone in their eighties who had a lifelong passion to write and illustrate children’s books. They never did, though, because back in early adulthood a bad experience in a drawing class robbed this budding children’s book author of any belief in their drawing skills. So, despite a lifelong passion, and 50 years of trying to improve their drawing skills, they never wrote the books they dreamed of writing.

A lot of people have similar negative experiences with learning maths. This led Jennifer Ruef, a professor of mathematics education, to coin the phrase “fragile math identity”. People who suffer from this grow to fear maths, avoiding failure by not taking on challenging classes or problems – which, of course, limits their chances of becoming better at the subject.

The fear of failure leads them to become risk averse and inflexible, and then to avoid challenges that could stimulate personal growth.

This is the key to understanding how trauma shapes your personality. Unresolved negative experiences make a person less flexible when to comes to handling emotions. Negative emotions foster self-limiting beliefs, or what Carol Dweck calls fixed mindsets.

Eventually a person’s belief that they can’t reach their goals becomes a bigger barrier than any obstacles they might normally face.

This lack of flexibility increases the time it takes to get over negative experiences. This is made worse in the absence of an empathetic person to discuss the experience with, someone who sees them and helps them put their emotions in context.

“Trauma is not what happens to us, but what we hold inside in the absence of an empathetic witness.”

– Peter Levine

An important step in overcoming trauma is reconsidering the people in your life. You need to be able to talk openly about your struggles and experiences. As Hardy says, “…if you’re serious about transforming your life, you need to surround yourself with a whole new cast of friends, mentors, and supporters.”

An example of this is an entrepreneur who regularly gets together with a group of friends who keep each other accountable. They each keep a tally of personal metrics – things like income and net worth, health numbers, even the quality of their relationships. This radical openness allows each of the friends to process their emotions and insecurities.

Trauma is a fixed, deeply internalised memory that leads a person to avoid living fully. If the person learns to face difficult experiences and memories, usually with the help of others, the possibility opens up to reinterpret past experiences and learn from them. This might happen through friendships, or therapy, or both. The person can then learn to become more emotionally flexible and more able to imagine their future, self-growing and enjoying life more.

“Healthy memories change over time. A growing person continually has a changing past, expanding in meaning and usefulness.”

–- Benjamin Hardy

How Our Story Shapes Our Personality

We instinctively try to create meaning from the experiences we have. We use stories to do this. The story helps us define the experience, what happened, what is says about us, and what it says about the way the world works.

This is natural. But, if we’re not careful, these stories can define us in very fixed and limiting ways.

Our memory isn’t a perfect recorder. We create the memory in the way we tell the story of our experience. We can choose to describe the same experience either as a failure or as the courage to overcome a disappointment. It’s a lesson I had in talking my PhD attempt.

It’s possible to strategically rewrite your history to serve the person you want to become.

An example of this is “the gap and the gain” idea Hardy cites from Dan Sullivan. The gap mindset constantly frames experiences as disappointments which prove you don’t measure up to the standard and will struggle to improve. The gain mindset would frame the experiences as proof of the progress you’ve already made and your potential to improve.

“Your authentic self is your future self. Who you aspire to be.”

– Benjamin Hardy

Shifting Our Subconscious

Emotions happen in our bodies. Our bodies are like living memory banks. This idea was popularised by Bessel van der Kolk’s book, The Body Keeps The Score. The language with which the mind and body speak to each other is emotions.

Our bodies become accustomed to having the same kinds of emotions and the chemicals that carry those emotions. Our bodies have an “internal thermostat” for emotions and seek to return to familiar (but not necessarily comfortable) emotional states (as described in The Big Leap, by Gay Hendricks).

If we don’t process these emotions and deal with our subconscious, then our body may manifest these repressed emotions as pain. As John Sarno explains in Healing Back Pain, our body can manifest physical pain as a way to distract attention from emotional pain. Physical pain can even be your inner self crying out for attention. As Steven Ozanich explains in The Great Pain Deception, pain can be a manifestation of “…unresolved internal conflict”.

Our subconscious is like a circuit that’s constantly running throughout our bodies. It keeps pulling us back to familiar emotional states, even if those are unpleasant. We must engage in actions that rewire the circuit. Hardy recommends three: keeping a journal to log emotions; practising fasting; and making regular charitable gifts. There are more, however, which are explored in the Science of Well-Being course. IL9

Designing Your Personality

In a 1979 study by Ellen Langer, graduate students designed the interior of a building so it looked like something from 1959, then invited eight men in their seventies and eighties to live in it for five days. Pretty soon they changed. Not only did they act like they were younger, being more active; they changed physically. They got taller and their hearing, eyesight, memory and appetite improved.

They improved by being in an environment designed for them.

If the environment around us doesn’t change, then we tend to fall into routines, with predictable attitudes, behaviours and habits. Our personality remains constant because our environment encourages us to be consistent.

This is perhaps most evident in the people around you and the role your place in society has in shaping your self-identity and the way you behave. Your social group will influence everything from health to ethics, academic achievement, productivity and success.

Hardy suggests you be intentional about designing the environment around you. One way to do this is make sure you’re surrounded by reminders of what is possible for you and not just reminders of who you were. You should ask whether your environment pushes you forward or pulls you back. You might what to swap those old posters full of nostalgia for art that challenges you to see the world in new ways.

“Look at your closet and get rid of anything your future self wouldn’t wear.”

– Benjamin Hardy

Being selective and setting boundaries isn’t limited to things; it also applies to what has your attention. There are so many things you could focus on, but precious few that really matter if you have clear goals and desires. In order to be focused you’ll need to become comfortable with things that might have the attention of those around you.

Finally, you can force change by imposing limitations. Hardy recounts the story of Christina Tosí, of Momofuku Milk Bar fame, who was writing food safety plans for the Momofuku restaurants when David Chang challenged her to come up with a dessert that would be served that night in the restaurant. He then pushed her again to open her own outlet, Milk Bar, to sell her fantastic ideas.

When you commit to doing something, with a time constraint, where quality matters, you find more motivation to succeed. Hardy calls this a forcing function and suggests we build these kinds of loops into our regular life.

Ultimately, this enhances our imagination, giving us permission to dream bigger, to see ourselves doing things we didn’t fully believe we were going to be able to do.

Your Personality As You Age

But as you get older, it almost feels like society is designed to lock you into the past and into self-limiting stories. Nostalgia is the default mode. Even digital technology feeds you the past through algorithms, suggested playlists and recommended viewing. It’s assumed that from your thirties onwards you are looking backwards more often than you are looking forwards.

I wish Hardy had spent more time on the role of people in your life. Knowing when to cut people from your social circle. Or how to coach those who remain to have the right kind of mindset for future-oriented personality growth. This is a challenge that never goes away.

Personality Isn’t Permanent is a welcome reminder that you can rewrite your self-limiting stories, that your past isn’t your destiny, and that your personality ought to evolve over time. You can change, and here’s the science to prove it.

The post Personality Isn’t Permanent appeared first on Fernando Gros.

August 29, 2020

Weekend Wednesday

In a recent video, YouTuber and podcaster CGP Grey explained his newfound enthusiasm for what he calls Weekend Wednesday. Instead of structuring your week with five working days followed by a two-day weekend, you could follow a plan of two days of work, followed by a day of rest, followed by three days of work, and another day of rest.

Before you read on, take a few minutes to watch his explanation of the idea.

Watching Grey’s video made me angry. Not because I disagree. On the contrary, I’ve worked this way for most of my adult life. But I had never written about it. Now there’s an excellent video with this “new idea.” And I’m here at my desk muttering “Yeah, but I’ve done this for years.”

The Evolution Of My Weekend Wednesday

Five days of work. Two days of rest. We inherit this idea from family and school. But at some point it’s worth asking: why? Isn’t there another way?

I started wondering about this in my late teens. A lot of the best music gigs, especially if you wanted to see jazz, or experimental music, were on Monday nights. This made no sense if you looked at it from the perspective of the regular working week. But it made complete sense if the audiences for those gigs weren’t people who worked Monday to Friday jobs, but people who were busy working on the weekends. You can’t go and see live music on a Saturday night if your job means you’re also on stage then.

Those Monday night gigs often had a different vibe. The audiences were quieter; more obviously focused on the music. More intense. And the musicians were more daring. Feeling less constrained by the need to entertain a crowd that was only half-listening, the musicians were more willing to explore challenging ideas with an audience that was interested in being pushed creatively.

The same was true in other ways. The people who visited galleries in the mornings during the week, or who went to the cinema on weekdays, had a different intensity.

An Idea Becomes A Habit

Pretty soon a pattern was set. I would joke that the problem with going out on a Saturday night was that everywhere was full of the kind of people who only went out on Saturday nights. But behind the joke was a growing personal insight. The stuff most of us cram into the weekend, like going to the cinema, or to see live music, or to enjoy a gallery or restaurant, was best enjoyed during the week.

This notion had become formalised by the time my daughter was old enough to start pre-school. I took every Wednesday off and we spent the whole day together. Saturdays became mother-and-daughter days, which left me free to catch up on the week, giving me an extra day or at least a half-day to work.

And whenever I could, I kept up that pattern. Saturdays often had a specific focus. For several years they were when I recorded and edited podcasts. Or focused on editing photos. Sometimes I would swap Saturday and Sunday around, almost always to suit family commitments.

But the split week pattern, with a day off in the middle of the week, continued.

The Pandemic Challenges Weekend Wednesday

The pattern has been challenged during the pandemic. Just like other established patterns that had served me well. I got sucked back into a regular five plus two pattern, like everyone in the household.

But this didn’t have to happen.

In this season of working from home, and with a student daughter at university (or on summer holidays), we could’ve negotiated a different arrangement.

Except I got lulled into accepting the normal.

Watching the Wednesday Weekend video was a much-needed reminder of a pattern that had served me so well for so long. I’m now wondering if the emotional toll of the pandemic is only partly to blame for my feelings of exhaustion.

The Rest Day

Test match cricket used to include a rest day. The five-day match was split into three days of cricket, followed by a rest day, then two more days to decide the result. It was a throwback to the days when it was supposedly a “gentleman’s sport” and was done away with as the game modernised in the 1980s and 90s.

But the idea that three days of work is enough and should be followed by a rest is fascinating. Particularly given everything we now know about the role of rest and a wandering mind for creativity. Taking a break after three days stops problems from overwhelming you, and gives you more chances to put work into context with the rest of your life.

Sometimes I dream about a schedule that is simply three days on, one day off throughout the year, ignoring the sequence of seven-day weeks. Of course, this would put you out of sync with the rest of society. But regular routines are increasingly uncommon anyway. Sports, for example, no longer follow their old-established start times and kick-offs. Once you get into adulthood, finding time to see friends typically takes a bit of to and fro to find a shared space in both (or all) schedules.

I’m shelving that dream for now. But as the hot days of summer fade, I am going back to Weekend Wednesday. There might not be anywhere to go yet. Galleries, museums, and live shows still feel like something we are months away from being able to enjoy. But long restorative walks in the park, or afternoons spent reading or playing guitar, are very much available and are there to be enjoyed.

The post Weekend Wednesday appeared first on Fernando Gros.

August 28, 2020

Manage Your Energy Not Your Time

“It’s Friday afternoon. I won’t do this now. Bring it back on Monday.”

“But my boss said it’s urgent.”

“Bring it back on Monday.”

For a few years in my early twenties I had a regular job. I was a clerk, in a bank, with short hair, a suit and tie. It was a day job. It was a means to buying more music gear, airplane tickets, and a car I could get home in without having to call roadside repair or a tow truck.

Occasionally the job managed to be interesting. This was usually when I could figure out a way to get away from my department, which dealt with car finance, and have meetings in other parts of the bank.

One example of this was my visits to the “credit cycle guy” as everyone called him. Every now and then there would be a car lease that for some reason didn’t comply with the normal rules. And there was only one guy in the bank who could sign off on it. So I would walk down to an office that was full to the ceiling with papers and files, and which was where the Vice President for Credit Cycle Management was to be found.

My first visit to that office involved a loan for a Rolls-Royce. The car cost more than most people’s homes. But that wasn’t the problem. We had people on our floor who could sign off on a lease that big.

What the buyer wanted was for all the optional extras to be included in the lease. One of the extras was a matching picnic set, with folding tables and chairs, that slotted into a custom-made space in the boot. We didn’t have a category for furniture in our car finance policy!

Everyone – our sales reps, our preferred dealer, and our private banking people – was desperate to get this VIP deal approved. I volunteered to go see the credit cycle guy. No-one else seemed to want to. And on a Friday afternoon I was told: “come back on Monday!”

Know Your Energy Levels And Your Limits

Feeling a little chastened and wary, I returned on Monday morning. He sat me down and explained why he had sent me away.

Friday afternoons were not a good time for complex decisions. You’re tired. Maybe you had too much for lunch. You’re thinking about the weekend. You rush things. You make mistakes.

This was my introduction to the idea that there are right and wrong times to do things, based on how your body is behaving, and what your energy levels are.

Managing Energy Levels

An influential 2007 article in the Harvard Business Review called Manage Your Energy, Not Your Time popularised the idea of thinking about your energy as it relates to your work.

Time is a fixed resource. You can’t add more hours to your day. At first, managing your time makes you a lot more productive. Then the incremental improvements start to taper off. Pretty soon you run the risk of turning time management into something that consumes more time than it’s worth.

By contrast, your energy levels are suprisingly elastic. You can bring more energy to your day by getting enough sleep, or being well rested. You can manage your energy during the day by eating well, or taking breaks. Your habits and routines, from exercising regularly to taking care of your frame of mind, can help you bring the most energy to what you do.

You can also do a lot to match the tasks that require the most energy (or require you to be at your best) to the times of day when you have the most energy available.

This involves knowing yourself a bit. Maybe you take on the most complicated or demanding challenges in the morning, when you feel fresh? Perhaps you put those mundane, repetitive tasks into the afternoon, when you feel a little flat? Or you spend a little time on those creative things in the early evening, when you feel relaxed, but not yet too tired?

And of course, this involves not scheduling challenging tasks at those times when you aren’t at your best. Like not looking at complicated deals late on a Friday afternoon.

Energy And Productivity

Time is an equally distributed resource. We all have the same number of hours in a day. You can try to hack your way to more time by sleeping less, but it doesn’t pay off in the long run.

Energy isn’t equally distributed. Consider the people who turn up every Monday complaining about another working week. That kind of mindset makes it impossible to be productive or to be at your best.

We’ve all had that feeling when we do something and feel great while doing it. We know that when we turn up at our best, physically, mentally, emotionally, we’re at our most productive. An hour at our best is worth more than an hour expertly crammed full of stuff we don’t feel up to taking on.

Self-Knowledge Is The Key To Using Energy Well

Thinking back to the credit cycle guy, it’s clear he was trying to manage his energy. Who knows what mistakes he made, or saw, that made him enforce his Friday afternoon rule.

The office gossip was that he was grumpy and difficult to deal with. If all I had to go on was my experience taking a fraught request to him late one Friday afternoon, I might’ve agreed with them. But the guy I got to know, who was into golf and sailing and loved his grandkids, was very different. He was smart, had a nice grasp of personal boundaries, knew his limitations, managed his energy, and was good at his job.

I still don’t really know what the credit cycle guy did during the rest of his time in the bank. But the lesson about managing your energy, picking when to do things and when to avoid doing them, has stuck with me ever since.

The post Manage Your Energy Not Your Time appeared first on Fernando Gros.

August 18, 2020

You Don’t Need To Be A Hero To Change Your Habits

‘15 minutes a day is enough.’

‘It can’t be.’

‘Just try it.’

I used to teach guitar. It’s not something I talk about. I did it because other guitarists did it. And it helped pay for strings and food.

The question of practice would always come up. Even people who weren’t getting lessons would ask, ‘How much do you have to practise?’

Before answering that question, you pause. Because what you, as a professional musician, do to practise isn’t what a student, especially a beginner, might need.

Back then, my guitar practice schedule was pretty out there. Two to three hours a day was normal. And that was just for the mechanics of playing. Add more time for learning theory or new songs. Add even more for doing maintenance on guitars, experimenting with recording and effects, writing arrangements, or just jamming with friends.

But all of that isn’t what someone is asking you when, a few months into learning the instrument, they ask, ‘How much practice should I do?’

So I settled on saying, ‘Fifteen minutes a day.’

How I got there was a simple process. I looked at the amount of material a beginner or intermediate guitarist might practise, assuming they were getting lessons weekly or fortnightly and assuming they wanted to make a step change in their playing over the course a year.

Then I thought, assuming they practised every day, in a focussed and distraction-free way, what was the minimum time they needed to play through the material. And somewhere from 10 to 15 minutes felt like the answer.

I asked my students to do exactly that. Practise 15 minutes a day. Never less. They all got better. A lot better.

I didn’t ask them to practise like I did. I asked them to practise the way they needed.

Heroism Stops You From Changing Habits

We overestimate how much effort is required to develop a habit, whether it’s practising to learn a musical instrument or improving a skill we already have – and mostly because we underestimate how effective a small effort can be at driving change. Especially if we sustain that effort for a long period.

So we’re tempted to make one of the greatest mistakes of all: trying to change heroically.

We muster equal parts courage and delusion and march forth with a plan to radically alter how we live. We make our goals as big and bold as possible.

And we fail.

We fail to recognise where the effort should go.

We make one big effort, instead of making a lot of small efforts.

Practising 15 minutes a day is doable because there are plenty of 15-minute slots you can slip the practice into. There are fewer 60-minute slots. And, if you need to add some time for getting ready, you are still only 20 minutes. But 65 minutes suddenly feels like two hours. And if you practise an hour a day, every day, you’re going to be changing strings a lot more often, which is more time and effort you have to budget for. The resistance comes when the change we strive for is so big.

Be Atomic Not Heroic

The tragedy is we usually don’t need to be heroic. Thinking we do holds us back from making all sorts of changes and improvements in our lives.

This is the key insight from James Clear’s book, Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones . A small change sustained for a long period can lead to a dramatic change.

Clear outlines four ways to build new habits, by making sure they are obvious, attractive, easy to follow through on and satisfying.

He also suggests something I left out of the earlier story about guitar practice: change your environment.

Change Your Environment To Change Your Habits

‘Make a space to play guitar,’ I would tell students.

Don’t waste your time taking your guitar out of its case, trying to find your sheet music, setting up a stand, or finding somewhere to sit. Prepare the space. Have your guitar, music stand and sheet music ready. Make sure you have a chair or a stool and a decent light. Then, when it’s time to practise, you practise.

It’s like the opening lines of Wendell Berry’s poem, ‘How To Be a Poet’:

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

Creating the right environment removes the hesitation and decision making from the doing. Designing your environment to support good habits beats willpower every day of the week.

Design For Better Habits

This is the message of Brian Wansink’s book, Slim by Design: Mindless Eating Solutions for Everyday Life.

From a long-term study of more than 1,500 people who had struggled with diets, Wansink found the people who best managed to make sustained changes didn’t do so heroically. Rather, they made a few changes, usually just one or two, but they stuck with them, typically for at least 25 days a month. People who tried to make radical changes to their eating habits often got frustrated and gave up.

Wansink also found that kitchen design made a difference in people’s eating habits and health. Not how big, or pretty, or Instagram-worthy a kitchen was, but how it was filled. Having snacks or sugary cereals didn’t determine if people were fit or not, but having them out on display often did.

“Our Syracuse study showed we could roughly predict a person’s weight by the food they had sitting out.”

– Brian Wansink

A number of design-driven changes to the environment – from making the kitchen less “loungable,” making healthier snacks visible while hiding less healthy ones, and by making it easier to cook from scratch – all supported good eating habits.

When it comes to changing our habits, it’s best to start out small, stick with it, then design the spaces around us to support the change.

The post You Don’t Need To Be A Hero To Change Your Habits appeared first on Fernando Gros.