Fernando Gros's Blog, page 14

December 8, 2020

Reading To Become A Better Writer

In order to become a better writer you have to read. A lot. It’s pretty standard advice. Everyone agrees: reading improves the quality of your writing, so read the work of good writers.

Stephen King put it pretty bluntly.

“…if you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot. There’s no way around these two things that I’m aware of, no shortcut.”

This advice is universal for a reason – it works. Reading widens your vocabulary. It introduces you to different kinds of ideas and different ways of telling stories. Reading opens you up to a world of human experience beyond your own. And as you read you develop the skills and stamina you’ll need to critically assess and edit your own writing.

But there’s one way in which this advice can go wrong, and it often begins with Shakespeare.

The Danger Of Asking The Internet

Imagine being that aspiring writer. You want to improve. You’re ready to read. But read what? So you go online and ask for recommendations. In they come: Joyce, Tolstoy, Melville, Proust, etc. And of course Shakespeare. The heavy hitters of classic literature all get dumped on you.

Follow this advice and things could quickly go wrong. Especially if you are not already a prolific reader. Soon you’ll be 200 pages into Infinte Jest, wondering if you should just give up on writing and take up something less arduous, maybe mountain climbing, or crocodile farming.

Book recommendations often say more about the people making the recommendations than the needs of those asking for something to read. People want to look clever and sophisticated so they recommend the heaviest and most difficult books they’ve read.

For all you know, the person recommending Dostoyevsky or Shakespeare has never read a line of their work. Or perhaps they did once, in college, or high school. But it’s unlikely they jumped from reading “Thou knowest the mask of night is on my face…” to answer a few questions on Reddit or Twitter.

Reading Like A Reader

I’m not saying no-one reads these heavy classics. They do. At least, sometimes. But talk to readers, the kind of readers who’d rather point their eyes at a book than Netflix, and you’ll find they read more widely, more contemporaneously, and often more lowbrow than the stuff you find in “classics you need to read” lists.

In a bookstore, the shelves carrying the classics and “literature” comprise only a small part of the layout. Think about the other shelves. The bestsellers, the crime, the romance, the children’s books, and all the non-fiction, from cookbooks to world politics.

All those other shelves offer the vast array of ideas you can explore and audiences you can connect with as a writer.

All those books have readers. They could, one day, be readers of your work as well. If you learn to write for them.

Reading Like An Artist

Artistry is all about process. Regardless of whether you’re a photographer, musician, or writer, how you consume is just as important as what you consume. Your goal as an artist is to make work that will resonate with an audience.

As a writer you don’t read in order to fulfil some need for validation or as a qualification. You read in order to figure out how to express your ideas and share your stories in ways that your readers will connect with.

“It’s an artist’s duty to reflect the times in which we live.”

– Nina Simone

You’ll hear people say things like “Shakespeare knew how to shape a story.” Sure. Structure matters. Shakespeare did it well. But so do many contemporary writers. And so do film and TV makers. Good storytelling is all around you.

Which one did more of your potential readers enjoy this year – Hamlet or The Queen’s Gambit?

The same goes for Shakespeare’s famous skill with language. You might never write anything as poetic as even the most disposable lines Shakespeare wrote. But if you try to write like him you’ll come across as fake and insincere, a mere copy of a famous style.

Finding a style you can explore and imitate, at least to begin with, is part of how you discover your style. It’s similar to what musicians do. They start playing covers and standards. That’s the way to get on stage. Then the original songs and the unique style develop as their musical vocabulary grows.

It’s the same with writing. You’ll struggle to grow if you don’t read writers who speak a similar language to yours, who live in a similar moment, who tell similar stories.

Reading Like A Writer

So, how do you read like a writer? Start with what you want to write. And, spoiler alert, unless you’re trying to write historial plays in an Elizabethan style, then Shakespeare didn’t write like you.

If you want to write personal essays, then read personal essays. Read travel memoirs if you want to write about travel. Start by making a short list of four or five writers who are currently writing in the style you want to emulate.

Since it’s 2020 and not 1620, add some diversity to your list. Don’t pick writers who all come from the same background, write for the same publications, or appear on the same bestseller lists.

You can take this further by paying attention to writers they mention, either in their work or maybe in interviews. Or take a look at the writers they are compared to, either in book blurbs or reviews.

Pretty soon you’ll have a reading list long enough to keep you going for some time. And all of it relevant to the style of writing you are hoping to make your own.

So, Do The Classics Not Matter

I want to acknowledge a bit of privilege here. I read a lot of classsics in high school. Not because I went to a great school; I didn’t. It was a terrible institution filled with demoralised teachers who were expected to train future factory workers.

But, thanks to some visionaries on the state school board, we were assigned a little bit of literature in English classes. And in my youthful naïveté I took that as a sign that I should trawl through the mostly untouched literature and poetry sections of the school library.

Did those books shape me? Yes. Did they inspire me to become a writer? No.

The distance between my world and those of Hardy, or James, or Solzhenitsyn was too great. I couldn’t quote them in regular conversation, to make friends laugh, or break the ice with girls I wanted to talk to.

Song lyrics, lines from movies, or more recent books and magazine articles were different. I still remember the moment I read this line in The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, by Douglas Adams.

“The ships hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don’t.”

The wit in that sentence, the literary device that makes it funny, was a tool I could use. As a writer, that’s what you want from your reading – tools you can use.

By all means read the classics if you’re inclined to do so. But read contemporary work too. Read writers who write the way you want to write. Read the writers your readers enjoy. Remember to read like an artist and read like a writer – using your reading as a way to become a better writer yourself.

The post Reading To Become A Better Writer appeared first on Fernando Gros.

December 3, 2020

Twyla Tharp On Choosing Which Friends To Keep

The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp is the first book I recommend when asked about the creative process. It’s full of lessons and examples from Tharp’s long and illustrious career in choreography and dance. The Creative Habit is also completely free of the usual abstractions, clichés, and romanticisation of art you often find in books about creativity.

So when Tharp released a book on growing older (Tharp is now 79), it promised to be something special.

Keep It Moving: Lessons for The Rest of Your Life doesn’t disappoint. With a beautiful mix of honesty, wit, and just the right amount of storytelling, Tharp lights up a path for us to follow towards enjoying our transition to old age.

Tharp On Choosing Which Friends To Keep

Keep It Moving is a rebellious and counter-cultural book. Tharp contends that society encourages people to become quieter, smaller, less mobile and more conservative as they get older. In contrast, Tharp’s advice pushes against this, encouraging you to express yourself, take up the space you are entitled to, and continue to move and enjoy your body.

One piece of advice in particular stands out – selectively revising the circle of people you spend time with.

Tharp uses the example of dancers who, as they age, are fighting the decline of their physical ability. It’s a battle they will lose. The best a dancer can do is lengthen the window of time when their experience and skill allow them to dance at the highest level, but when injury and the inevitable process of slowing down haven’t robbed them of the ability to perform.

Tharp says they can only do this with a positive attitude. If the dancer indulges their doubts or feelings of uncertainty, or internalises the negative attitudes of people around them, then they won’t have the energy for the fight. They will give in early.

Saying no to negativity and people’s negative attitudes is the same as saying no to bad food or other bad habits. It’s an investment in your potential.

“The older I get, the more I say no.”

– Twyla Tharp

The Wisdom Of Choosing Your Friends Carefully

The wisdom around carefully choosing the people you spend time is deep and vast. Jim Rohn famously said, “You are the average of the five people you spend time with.” Study after study confirmed that the people in your social circle are predictors for your weight, your health and your happiness.

In Algorithms to Live By, Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths describe the way people have smaller social networks as they age. This isn’t, as commonly explained, because of some deficit in older people’s way of life. Rather, it’s the result the way older people “…strategically and adaptively cultivate their social networks to maximize social and emotional gains and minimize social and emotional risks.”

When I wrote Seven Kinds of People You Need in Your Creative Universe back in 2011, one thing that stood out was the response from creative people I admired. Artists, craftspeople, musicians, and folks who had started and ran successful creative business all agreed that being intentional about the people in your life, and particularly those you called friends, was crucial to being at your best and doing your best work.

Tharp’s Method For Auditing Your Social Circle

How do you decide which friends and acquaintances to keep? Tharp suggests you let dopamine do the work for you. Draw two columns on a piece of paper. Go through the people you know, and notice how you feel about the prospect of seeing them. The ones who make you feel good go in the right column. The ones who don’t go on the left.

What matters here is how positive the people make you feel. Not how nice, or pretty, or popular they are, but how interesting, inspiring and stimulating their company is.

Now look at both lists and think about where you spend the most time. Is it with ‘…people who bring the best out of you or people who bring you down?’

It Begins With Saying No

Tharp says you should ‘give yourself permission to say no’ to people on the negative side of your list. It says a lot that we feel we need permission to do this. But it’s so true.

None of this is easy. Saying no to people is hard. It might take some effort to reconfigure your social life. But to maximise the creativity and freedom you experience, you need to minimise your exposure to cynicism and negativity.

As Parker J. Palmer puts it, we build our well-being by ‘…choosing each day things that enliven one’s selfhood and resisting things that do not.’

In the same way that we invest in our physical health by eating well and exercising, we also invest in our emotional health by consuming good ideas and spending time with people who inspire our potential.

And, as we get older, taking care of health becomes more urgent than ever.

The post Twyla Tharp On Choosing Which Friends To Keep appeared first on Fernando Gros.

November 25, 2020

On Not Losing Hope

The UK is going back into lockdown. Sort of. It’s not the kind of lockdown which Melbourne just successfully endured, allowing them to tame a rapidly accelerating outbreak and drive the number of new cases down to zero. It’s not the kind of lockdown Adelaide went into when it appeared a dangerous outbreak was threading there.

Rather, it’s a lockdown full of exceptions, and protests, and general lack of compliance. But it’s a lockdown all the same. We’re told it’s until early December. Most people expect it will be longer. Possibly lasting the whole winter.

We got picked for a random test. The courier arrived this morning to pick up the sample. He wasn’t wearing a mask and stood under the arch of our doorway expecting me to hand the parcel to him. We need to redefine our sense of farce and irony to accommodate the idea of someone sent by the government failing to follow basic health safety in the middle of a pandemic.

Hope In Covidtime

All this raises the question of how to cope, how to hold onto hope, and how to carry on living well with such an uncertain future ahead of us.

When news of viable vaccines hit a few weeks ago, it was disconcerting to see how plans for summer 2021 started trending on social media. So many people seemed to expect that, come May, life would be totally back to ‘normal’, and it would be a summer full of festivals and parties.

Maybe. But probably not.

We’re still not close to any vaccine being rolled out at scale. And the effort required to ramp up production to the number of doses needed for restrictions to go away is going to be epic.

And when the vaccine starts being rolled out – assuming you’re in a country that does this well – you (and I) won’t be the first to get it. We’ll be waiting in line behind healthcare workers and front line staff.

When the pandemic started, many expected it to be over by the summer. Then they expected it to be over when schools and universities went back, then by Christmas. If those predictions were so wrong, why expect fresh predictions like summer 2021 will be right?

Those predictions were hopeful. But they were wrong. Because that’s not the right kind of hope, the kind of hope we need right now.

How To Maintain Hope

Imagine you’re lost in the wilderness. Conditions are bad. You don’t know how far it will be to safety. How do you avoid losing hope? How do you keep going?

Blair Braverman’s answer is to ”act like you’re going forever.” I mentioned this in a recent post on having a good mindset, but it bears repeating. If conditions are difficult and uncertain, then the safest strategy is to assume the journey will be long.

Don’t get lured into the false hope and inevitable disappointment of expecting rescue to happen soon.

Victor Frankl And Hope In The Darkest Times

We find a similar message in Viktor Frankl’s haunting book, Man’s Search For Meaning. Writing from his experiences in the Nazi concentration camps of WW2, Frankl tries to understand what allowed some people to survive and others to give up.

At first, everyone felt lost and full of despair. But some struggled to move on. In terms of stages of grief, they were stuck in denial and negotiation. They found hope in fantasising about how circumstances would change, perhaps through imminent escape or rescue. Their spirit broke when that didn’t happen.

The people who coped better were more internally motivated. They focussed more on what life meant to them rather than what life was supposed to do for them. They were better able to find small moments of humour or joy amid the horror. Or they focused on the tasks they could do, given their situation, which added meaning to their days.

Of course our situation isn’t as brutal or stark. Lockdowns and quarantine are nothing like concentration camps. But Frankl wrote from the harshest of human experiences in order to inspire all of us when we faced suffering and uncertainty in our own lives.

Frankl On Re-Entering The World

The struggles didn’t end once people regained their freedom. Frankl said survivors often returned to society with complex feelings of bitterness and disillusionment. The world didn’t seem to care much, either about the suffering that they’d gone through, or human suffering in general. This made many survivors feel bitter. And freedom wasn’t as wonderful or free from suffering as they had hoped, which made them disillusioned.

Having fun wasn’t enough.

Again, the internal motivation, your personal “why,” was what mattered. Just having freedom wasn’t satisfying. A clear sense of why freedom mattered, what do with that freedom, especially in ways that helped and supported other people, gave survivors a sense of meaning that helped them enjoy their lives again.

A Recipe For Hope

One day this will all end. We won’t “go back to normal.” We’ll emerge in a new reality. A changed world. How do we hold onto hope now and develop a mindset for that future?

Here are a few suggestions.

1. Believe in a better future. This will end one day. Restrictions will ease. Freedom will return. We’ll be able to move and connect again.

2. Accept that it might take longer than expected. Disasters don’t conform to our timetables and wishes. We should avoid false hope that it will end quickly or conveniently. So plan your life assuming it will last a while and set yourself up to cope with that.

3. Focus on your internal motivations. This is the time to reflect on what matters to you. Why do you want freedom, and what will you do with it when it returns?

This has been a year like no other. There’s been plenty to make us question human nature, but also so much innovation and inspiration as people respond to the challenges before us. There are reasons to be hopeful. But we also need to clarify what we hope for. Then make that happen as the world opens up for us again.

The post On Not Losing Hope appeared first on Fernando Gros.

November 21, 2020

Work Blocks And Hyper-Scheduling

When the pandemic hit and people started working from home, a fascinating thing happened. Week after week, you’d read online articles, comments, and social media posts about how people were struggling to maintain a sense of routine.

Some lost track of what day it was or never got out of their pyjamas. Others saw the line between their professional and personal life blur as they worked ever longer hours.

People missed the way their workplaces, and their daily commute, structured their days.

Why We need Work Blocks

Back when I quit academia for creative work, I was lost. Totally lost. After years of working within external structures that told me where to be and what to work on, having to create my own routine out of thin air felt overwhelming.

Since then I’ve done what every artist, freelancer, and ‘company of one’ who works from home has done. I created a structure. Work blocks were the result of a decade of thinking about how to schedule time as a full-time creative and stay-at-home parent.

A work block is a chunk of time you assign to a defined task or a group of similar tasks. Work blocks are usually at least an hour long (mine are 90 minutes or 2 hours). Within the block, you might move from one app to another, or take breaks, but the time is focussed on one thing or a set of very similar things.

So, rather than doing email in tiny bursts scattered throughout your day, you might decide to dedicate a whole work block to it (and perhaps other communication). Or a work block may be focussed on a piece of work, like editing a batch of photos, or rewriting an essay.

Work Blocks And Scheduling

The 2014 article on using work blocks has been an evergreen favourite for readers of this blog. It explained the way I organised my day around four equal blocks of time, four short recurring breaks, and some long chunks for lunch and dinner, together with a regular night-time routine.

My use of the idea has evolved since then, but work blocks still inform the way I schedule things today.

If you work from home, structuring your days will help you stay focussed. But there’s no need to replicate an office style of working, especially since working from home can be more efficient and productive.

Work blocks can help you avoid constantly switching between tasks. They can help you block the times of day best suited to certain tasks. And dividing your day into bigger chunks of time can help you find a sense of flow.

Work blocks also help you say no. If you’re overwhelmed with all the tasks you need to do, then maybe the answer is as simple as having fewer tasks. But fewer tasks are only possible with fewer commitments. Decide what really matters. If you can’t make a block of time for something, maybe you shouldn’t make time for it at all.

Work blocks are a way to set your priorities.

Often the term work blocks appears alongside the concept of hyper-scheduling. But the differences are important.

Hyper-Scheduling

If you’re anything like me, the term hyper-scheduling suggests an aggressively overfilled schedule, maybe something alarming and anxiety-inducing like this:

It looks intolerable, but a lot of people live like that – possibly by design, as they try to control every variable in their life, but more often by chance, as they react to everything that comes up, including every distraction and call for attention, without noticing how fragmented their schedule really is.

It’s only through deep self-reflection, maybe journaling or time and habit tracking, that we might become aware of the routine chaos.

Hyper-scheduling responds to this chaos by taking control of every slice of time in your day. I don’t use – or recommend – this approach. It foments anxiety and stifles creativity.

Using Daily Themes To Batch Schedules

One common productivity idea is to batch similar tasks as a way to increase your sense of flow and avoid the potential for distraction when you switch tasks.

I’m thankful to Mike Vardy for introducing me to the idea of themes as a way to batch similar tasks. You might decide that Monday is your admin day, so you batch all admin-related tasks onto that day. Or Tuesday is your learning day, so you batch things like background reading, coursework, or other kinds of research onto that day.

This brings more order to the chaos and reduces the feeling that your days are full of random task switching.

With work blocks, you artfully streamline this even further.

Work Blocks Revisited

Over time, I had to evolve my approach to work blocks. Self-reflection is essential to making any productivity idea practicable, and my approach was still too random. Using Mike Vardy’s daily themes idea to batch similar work blocks together created this kind of schedule, which is how I worked for most of 2016–2019.

After a while, I started to question having the blocks the same size. Some activities lend themselves to larger blocks; some to smaller blocks. Trying to do all my email in one big weekly batch seemed like a good idea. But it was exhausting and anxiety-inducing. Splitting that into two much smaller blocks proved to be efficient and enjoyable.

Also, mornings and afternoons are different. My mornings are most productive when focussed on big, creatively demanding tasks. Typically, that’s writing. Afternoons are better suited to smaller work blocks, switching between tasks, doing things that involve more routinised workflows, or other chores.

By late 2019, my schedule evolved to look more like this. With the time required to walk to and from the studio, Pilates used to take out two mornings a week. Since lockdown, video lessons mean they take not just a different time of day but also much less time. Email was split into two blocks. Planning on Sunday mornings got a much bigger block of time.

And there’s a lot more white space.

The Danger Of Overscheduling

Whatever approach you take to scheduling your time, it’s important to avoid overscheduling. It’s hard to move mindfully through your day when all your events, meetings, and tasks are scheduled right up against each other.

Plenty of white space is important. It makes it easier to cope with interruptions, tasks taking longer than expected, having good transitions between activities, and ending your day well. But there’s also another reason.

Creativity.

Having some looseness in your schedule is essential for creativity. Giving yourself time in the day to let your mind wander, to make personal observations, or maybe go for a walk are essential for letting your brain switch gears in ways that foster creativity.

This was well observed in Michael Lewis’s The Undoing Project. The book is about the collaboration between Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Their work on decision making gave rise to the field of behavioural economics and later won Kahneman a Nobel Prize for economics. Both men were prolific and frequently published. They also enjoyed long, freewheeling conversations as a way to explore their ideas – something not possible in a rigidly structured schedule.

“The secret to doing good research is always to be a little underemployed. You waste years by not being able to waste hours.”

– Michael Lewis

Your schedule should liberate you. It should free you to focus and allow you to move through your life in a way that reflects your style. Work blocks can help you do this by encouraging you to set aside time each week for the activities that matter most.

The post Work Blocks And Hyper-Scheduling appeared first on Fernando Gros.

November 11, 2020

Time To Reclaim The Internet – And Our Minds

The fireworks have been going off all week here in London. The big display in the park nearby was cancelled, a casualty of the pandemic and the new (sort of) lockdown we find ourselves in. But, all over the neighbourhood, smaller displays have been going on for days.

The celebrations commemorate Guy Fawkes. He was a fundamentalist and terrorist, or zealous freedom-fighter, depending on how you tell the story. Either way, he paid with his life for his part in trying to blow up the government. Fawkes’ failure to kill the King 415 years ago is still celebrated every year with the lighting of fireworks and bonfires.

Democracy is a funny thing.

How We All Lost The Internet – And Our Minds

As far as inflammatory politics go, though, the past few years in the USA have been wild. This week, with fireworks randomly popping off in the background, we tuned in to reports from the presidential election. Would the USA vote for change – or more of the same?

During this pandemic, we’ve longed for normality. When will things return to normal? Or when will we have a new normal that isn’t so harsh, lonely, and restrictive?

The desire for normality sits within a larger question many of us have asked for the last five years. When will our public discourse, our online conversations, and our attempts to be informed about what’s going on in the world return to normal?

Part of my mission as a parent during these years has been to point, over and over again, at things happening in the USA, the UK, and elsewhere and say, ‘This isn’t normal.’

This week, for example, I’ve tried to draw attention away from baseless claims online and towards video of concession speeches from past presidents, like Jimmy Carter, and George Bush Sr. Again and again, the mission has been to point out this current season is not normal; neither is the way people act, nor the way they speak to each other.

Cleaning Up A Toxic Mess

It’s not enough to call out the toxicity of this moment. We have to face the mess and accept the work needed to clean it up.

A few years ago, I had a small operation. A cyst had grown on my back and I had to get it cut out. It was a small, messy thing, but it needed to be dealt with.

This week it flared up again. Not as bad, but it was painful and gross, at its worst just as the election results started to come in.

I hadn’t slept well and was curled up on the sofa, the pain in my back matched by a searing headache and general weariness. After breakfast and a dose of Ibuprofen, the news came through that Pennsylvania was swinging in favour of Joe Biden. I got up from the sofa and felt something cold and wet down my back. The abscess had burst.

The headache had also gone. And I took what felt like the first deep breath in a long while. It felt so good to just exhale.

I had a shower then called my doctor. Apparently, this was normal. Maybe even preferable. ‘The body is doing its job,’ the doctor said in a reassuring, doctorly voice.

Skin In The Game

After the 2016 election, I wrote about why people outside the USA care so much about these presidential elections. The piece was sparked in part by an internet troll who said my opinion didn’t matter because I had no ‘skin in the game’.

Sure, I don’t live in the USA, or pay taxes, which means I don’t vote. But the skin-in-the-game argument is false because we all live in the glow of the USA. If the country flames out, we all get sunburn.

The USA has more than 800 military bases in over 70 countries and has dropped bombs on at least 24 countries since WW2. While the USA’s economic supremacy is dwindling, it still has, at least for a few more years, the world’s largest economy. Moreover, from arts to education, media to technology, the US still leads and inspires the rest of the world.

We have skin in this game.

Withering In The Shadow

It’s been a brutal few years. Most of my friends owe some part of their work to life online. Virtual communities feed real-world work. And we’ve all suffered in recent years trying to protect smaller and smaller corners of the internet, trying to make sure it’s still okay to talk openly and authentically about things like art and creativity.

For many, it’s just been too hard.

It’s not just about one man or one office. But high office casts a long shadow. And this culture we live in feels coarse and harsh by design.

The surface of our online platforms is cut up, damaged and unsafe. Like an ice-skating rink after a hockey game. We need to run a Zamboni over it. Make it safe to play on again.

I hope that in the months and years ahead we can get our internet back. We can feel more comfortable sharing our stories and the things we make – without constant vigilance, not just against trolls, but against the troll in chief.

And I hope we don’t have to find new ways to drown out the amplified noise as we try to hear the inspiring voices we need to hear.

Regaining Our Optimism

One of the many disheartening aspects of the last four years is the way optimism has been co-opted as a tool of populist propaganda. Dave Chappelle highlighted it during his SNL monologue. A wedge was driven between optimism and science, between optimism and technology, between optimism and justice.

But it’s hard to be motivated for change without optimism, without hope, that the effort will lead to results.

It’s easy to forget, but just a few years ago we were on a path to increasing earnestness. Cynicism and sarcasm were the markers of being old, out of touch, short on ideas.

Authenticity was everything.

Time To Breathe Free

I hope this can be the start of a season of change. I hope we can all exhale and clean up the mess. The USA still clearly has a lot more work to do. This election is a bit like a new year’s resolution, more like deciding to go on a diet rather than shopping for clothes in a new size.

But it’s a step towards change and a reason to feel some hope.

We all, around the world, have work to do to fix the way we speak to each other. To stop shouting. Or cutting people out of conversations. To take responsibility for the harsh things that are said and the unjust ways people are treated.

Fear makes us react in strange ways, and there is so much fear. The last five years have been marked by fear.

In a year’s time, there’ll be more fireworks. Another election is always around the corner. Will we really be able to ‘breathe free’ by then?

The post Time To Reclaim The Internet – And Our Minds appeared first on Fernando Gros.

October 29, 2020

Clichés And Thought Terminating Clichés

Thought-terminating clichés are seemingly harmless and commonly used words and phrases that act to limit or stop conversation, discussion, or questioning.

“That’s just your opinion” and “It is what it is” and “I’m just saying” and of course “Whatever.” We hear these all the time. They, and other similar clichés, serve the same purpose.

They shut down conversations.

But they don’t just close down discussions. They also stop the questioning, the self-reflection, and the curious investigation that flows from good conversations.

The Nature of Thought-Terminating Clichés

Thought-terminating clichés derive their negative power in part from the nature of clichés as rhetorical devices that bypass new thinking. A cliché by nature is familiar. It suggests this thing is so similar to some other thing that no new descriptions or metaphors are required.

Think about the weather. It’s common to describe a rainy day as “miserable”. But are all rainy days like that? I can remember some very pleasant rainy days. And conversely, some sunny days that turned out to be very sad.

We might use only a few words to describe the weather, but in reality, there are thousands of shades of subtle difference, from one day to the next. Not all grey days are the same.

Clichés are to language what nostalgia is to the arts. Nostalgia can feel comforting and safe. But it can also cut you off from new experiences. They bypass having to deal with new ideas, new trends, new ways of doing things.

We Get Old Surprisingly Young

“Old people are just set in their ways.” That’s a thought-terminating cliché. The reality is, many people get set in their ways surprisingly early. Most have stopped listening to new music by their early 30s. Not started to listen to less new music, but stopped completely, entering a kind of “musical paralysis.”

Music is one of those parts of our culture that changes and evolves constantly. The sound or timbre of music reflects its age and the technology used in studios.

People start to dislike new music while still in their 20s. “Today’s music sucks” might be the reply. But isn’t that just a way to bypass the work of finding music you like among the many thousands of new songs released every year?

What Do Good Conversations Feel Like?

Conversations are open-ended exchanges of experience and ideas. The opposite of conversation isn’t silence, but a series of uninterrupted speeches, or monologues, where people just speak without exchanges or questions.

The anti-conversation obviously lacks the heat of disagreement. But it lacks the warmth of compassion and empathy as well. The closed-off encounter (I have my say, you have your say) means no one ever really says anything to anyone else.

This doesn’t mean conversations are or must be argumentative. You don’t have to fight, or even do philosophical martial arts, in order to have a meaningful exchange. In fact, the way many people resort to rhetorical tactics in arguments also kills the open and inquisitive vibe needed for conversations to happen.

Good conversations activate curiosity.

Why Clichés Kill Conversation

Clichés are singled out for criticism in all guides to writing well. They are seen as a mark of laziness; a tendency to use the most obvious and thoughtless way of expressing an idea. Stephen King, in On Writing, suggests that “…the use of clichéd similes, metaphors, and images” is often the result of “…not enough reading.”

Clichés don’t just make your writing look weak. They also weaken your connection to the reader. Clichés bypass the reader’s normal work of visualising and imagining what you are saying. When your ideas are replaced with a familiar image, the cliché, your writing becomes less memorable.

So, if clichés are the mark of bad writing, and they make your ideas less memorable, then why are they so popular?

The Role Of Thought Terminating Clichés

Conversations are not always welcome. Exploring ideas, asking questions, investigating stories, or following curiosity and imagination wherever it leads isn’t always acceptable.

Clichés have often been used as markers for the edge of acceptable debate in politics, especially in totalitarian regimes. This kind of language is satirised in both Brave New World and 1984.

But we also find thought-terminating clichés in democracies as well. Phrases like migrants, boat people, illegals, act in ways that load debates with superficial emotion in place of moral reasoning.

And they are perhaps most prevalent in folk wisdom and arguments based on so-called “common sense.”

They act to shut down conversations, or to move the conversation from a substantial footing (actual stuff in the world) that can be resolved, to an insubstantial one (ideas and emotions) which requires no resolution.

This is the insidious side of thought-terminating clichés. They turn someone’s request to be heard, to be taken seriously, to be given space, with a reply that basically says “I don’t really need to take you seriously,” but does so in an otherwise polite way.

Clichés Kill Creativity (And Democracy)

Clichés imply a sense of agreement. They suggest an obvious way to interpret reality. But at the core of creativity is a desire for divergent interpretations. OK, so it’s like this now, but why can’t it be better, different, or more fun some other way?

In a similar way, democracy needs creativity because many of the problems we try to face need new and novel solutions. We can’t get where we need to be by doing what we’ve always done. Fixing big problems requires creative thinking. Climate change, racial and social injustice, and controlling the pandemic and then rebuilding after it, are all very big problems indeed.

The Future For Clichés

Clichés, like nostalgia, can sometimes be fun. Perhaps they’re less like poison and more like sugar. A little is enough.

When expressing yourself, it’s worth pausing before using clichés. Is the idea I want to convey something simple? Then maybe a cliché is OK. After all, some days really are “hot as hell” and nothing more needs to be said about them.

Are you happy to be that predictable, though? Is your world that easy to explain? Or do you want the people around you to imagine with you all the possibilities for experiencing your world more deeply?

We must be more vigilant about clichés, especially thought-terminating clichés, the kind that close down conversations, that stop inquiry, and that make it so easy to avoid asking the questions we need to ask about how to make our world better.

The post Clichés And Thought Terminating Clichés appeared first on Fernando Gros.

October 22, 2020

Eddie Van Halen

I stood for a while in front of the Arctic white guitar. A kid in a crowded music store. It was a Korean-made clone of a Fender Stratocaster, but for less than a third of the price of the real thing. That meant I could afford to dream about taking it home. I was by myself, 16, and although I knew my way around a nylon string guitar, I’d never actually played an electric guitar before. Having travelled into the centre of town with cash in my pocket and the intention of buying a guitar, I now felt intimidated.

Once I had the guitar in my hands, it felt like the whole crowded store was waiting for me to play. I strummed a few chords, picked a handful of notes and meekly said: “I’ll take it.”

I’ve mentioned that guitar before, and how it reminded me of one Prince had played in a music video and of the guitar that Jimi Hendrix was often seen playing in posters and photos. That was the guitar I learnt to record with, the one that started me on the path from occasional player to serious musician. I took it to jam sessions, I led pre-show singalongs with the cast and crew of our high school theatre production, and I even played my first gig with it.

However, that guitar was a piece of shit.

The Genius Of Eddie Van Halen

In senior high school, my music tastes shifted away from the pop, funk and electronica that I’d been listening to and towards more muscular guitar music. Van Halen’s music, in particular, started to spend more and more time on my turntable.

Eddie Van Halen’s guitar playing sounded so fresh. By the time I got into his music, he was already a huge success, and Eddie was often featured in the guitar magazines I bought. Still, his playing sounded new, urgent, wild and unpredictable.

What also caught my attention, just as much as the music, were his guitars. Most guitarists customise their instruments in some way, but Van Halen did radical mad scientist-like surgery on his guitars. It’s no wonder his original copy of a Stratocaster (pictured above), made from DIY kit parts and bits salvaged from other guitars, came to be called the Frankenstrat!

How I Killed My First Guitar

My Stratocaster copy, that first guitar, was a lemon. By today’s standards, it would never have left the factory. If I knew then one tenth of what I now know about guitars, I would’ve put it down right away. It was noisy, it didn’t stay in tune and it had an irreparable fault in the neck that meant it would always be hard to play.

But, I kept looking at the photos of Eddie Van Halen, on stage with his red, white and black striped guitar. It was so ugly, hacked together in a thoroughly unprofessional way. At the same time, it was so cool, and it sounded amazing!

The sensible thing to do would’ve been to trade my terrible guitar in for a decent one. Instead, I doubled down on my mistake, spending way more than a new guitar would’ve cost on parts, enlisting my father’s help with rewiring the electronics, and refretting, refitting and refinishing the guitar.

The result was a guitar that sounded amazing, but not any easier to play. Eventually I bought another guitar, a Steinberger, inspired by one I saw Eddie playing on a concert video. I also modified that guitar, but not so radically, and it mostly played well.

The Van Halen Soundtrack

The soundtrack of the final days of my youth had a lot of Van Halen in it (from both eras, if there’re any fans reading this).That was a time when adult relationships felt unfathomably complex. Making music felt easy, and technology offered nothing but promising optimism.

But, it was also a time when everything I did felt riddled with mistakes. Sometimes, you can learn only by breaking things.

Eventually, I stopped listening to Van Halen’s music. My tastes changed. The lyrics didn’t connect anymore. And music styles kind of moved on. I don’t think I’ve put on a Van Halen album since the mid-90s.

But, when Eddie Van Halen passed and I gave into the inevitable nostalgia, long-forgotten lyrics started flowing from my lips and I could remember a surprising number of Eddie’s riffs and solos. While I wish the videos on YouTube were higher resolution, that doesn’t really matter because my memories are so vivid.

And, I kept that crappy old guitar. It was in pieces for decades. But I put it back together a few years ago and hung it on the wall of my Tokyo studio. Right now, it’s in storage again, along with most of my music gear. But, when I get it back, I’ll plug it in, and I know exactly whose music I’ll play.

The post Eddie Van Halen appeared first on Fernando Gros.

October 19, 2020

Readwise

As a kid, I would often borrow a book of quotations from my parents’ bookshelves. It had a mostly white cover, with a green and black geometric ʼ60s pattern, and it was part of a library of Reader’s Digest reference books.

The quotes, arranged by topic, were funnier, smarter, and more biting than the typical inspiration-lite quotes you find online now.

It’s been a dream of mine for years to recreate that sort of collection from my own reading. Rather than recycle familiar quotes, I always imagined a more vibrant personal library of ideas, expressed in concise ways, through fascinating quotes drawn from my own reading and research.

With Readwise this is possible.

The Readwise Ecosystem

Readwise is a piece of cloud-based software. You create an account online and access it via your browser or an iOS app. Readwise allows you to pull highlights from a variety of reading sources together into a digital stream which you can edit, manage, reorganise and tag to suit your personal interests.

What Readwise Replaced

Before using Readwise, I pulled highlights from my Kindle using the Bookcision applet. Then I would copy those into Bear.

This created a document for each book. But that’s not exactly useful for anything other than writing a review or summary of the book. Juxtaposing ideas from one book with similar (or contradictory) ideas from another isn’t made easy.

It’s also incomplete, because it doesn’t include highlights from physical books or sources other than the Kindle.

What Makes Books Useful

We read because it’s enjoyable. Whether it’s the thrill of a good story well told or the satisfaction of gaining a fresh perspective on life, the joy is discovering something new. The things we get from our reading – let’s call them ideas for the sake of simplicity – become useful when they interact with ideas from other things we’ve read, conversations we’ve had, and our experiences.

A system that holds onto these ideas is a useful tool for clarifying our thinking and decision-making.

The simplest way to do this is just write out a quote that inspires you and stick it on your wall, like a DIY motivational poster.

Readwise is simply a more robust and portable digital version of that.

How Readwise Works

Readwise is built on a three-stage workflow, described as Capture, Review, and Integrate. Capturing highlights and quotes is only the first stage in the process of any kind of research.

Readwise automates this stage. Your highlights are automatically pulled from your Kindle account. Then you can sync from other sources, like Pocket, Instapaper, Medium, and iBooks.

Importantly, Readwise also makes it easy to add highlights from books by using your iPhone camera to scan text. You can roll up Twitter threads and import them. You can import text via email. There’s also the option to add a browser extension to Chrome or use third-party web clipping apps.

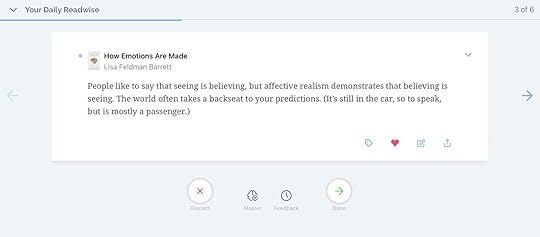

Once Readwise has captured highlights, you’ll be given the chance to review them either by visiting the app, email, or both. Readwise offers you a set of random highlights, together with the source and author, and you have a number of options to tag, like, keep, or discard the highlight.

Your Readwise feed is customisable in a number of ways. You can adjust the number of emails you receive and when they are sent. You can fine-tune how many highlights you review each day, from 1 to 15, and how new or old the highlights are. And it’s easy to adjust how often each book appears in your review feed.

Exporting from Readwise to notes apps like Notion, EverNote or Roam is easy, too. When you first connect Readwise to Notion, a database page is connected that pulls in your highlights. Not only does this pull in highlights as you add them, it also automatically updates in Notion to reflect changes when you edit your existing highlights in Readwise.

Using Readwise

Using Readwise is like surfing a perfectly curated feed of ideas you’ve already decided matter. It’s the ideal antidote to social media. Instead of navigating a random set of other people’s thoughts, you digest a sampling of ideas you know are relevant to your interests.

My feed is set to the default of five highlights per day. It takes only a few minutes but does a remarkable job of guiding my thinking throughout the day. Being reminded of important ideas puts everything else I see and read in context.

If you were doing a specific piece of writing, say a Longford essay or book, then it would be easy to adjust the references Readwise draws from to reflect only the topics you’re writing about.

I’ve done this to match my current writing interests for this blog: artistry, focus, and well-being.

It’s also easy to share quotes from Readwise. The app will even export quotes formatted for Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook. Or you can export quotes from within Readwise as plain text, which can be opened in a message, email, or any other shortcut you have set up.

Conclusion

Readwise has quickly become one of my favourite apps. Reviewing the highlights is one of my favourite moments in the day. In a short space of time, Readwise has become an essential part of my writing “stack”. And it’s become a fun way to share the best of what I’ve read, either on social media or directly with family and friends.

Now, finally, I’m a little bit closer to creating my own book of quotes, drawn from my own interests and reading experiences.

The post Readwise appeared first on Fernando Gros.

October 15, 2020

Advice For Living Well During This Pandemic

Too much water. Not enough yeast. The wrong temperature. Too long on the grill. Not long enough in the oven. The mistakes kept piling up in the kitchen.

Elsewhere similar problems arose. The missed spots while vacuuming. Or the poorly folded t-shirts. And the sofa cushions that didn’t go into the right spots.

In my work, articles weren’t falling into shape. Editing took far longer than normal. Even preparing photos for each blogpost seemed to invite all sorts of obvious mistakes.

It was pretty clear I was starting to feel burnt out.

Can We Live Well During This Pandemic?

The pandemic has been exhausting. Covidtime has disrupted our normal patterns, flooding our psyche with concern for the well-being of loved ones as we process the horrifying statistics of death and suffering and wonder how long this will continue.

This past week I’ve been drawing from some of the best advice I’ve read about how to approach this extraordinary year.

Learn From The Sled Dogs

From the wilds of Alaska, adventurer Blair Braverman wrote an extraordinary piece on facing hardship, with lessons learned from running sled dogs through arctic winters. It contained the best recommendation for how to deal with this pandemic.

“…if you don’t know how far you’re going, you need to act like you’re going forever.”

– Blair Braverman

On March 9, I cancelled all my appointments until “June at the earliest” and put off house renovations until “at least September”. It wasn’t that I thought the pandemic would end in three to six months. Of course it wouldn’t.

But I did think that would be enough time to rally around the need to make some sacrifices for the common good. That changes like mask wearing, common in much of East Asia, would be accepted globally. Or we’d notice how this challenge presented opportunities to be kinder, to rethink our patterns of consumption and work, and to be more ecologically sensitive.

It didn’t work out that way (at least not where I live), and now we face an indefinite future of limited travel and ongoing restrictions.

So, it makes sense to assume this will last forever. It won’t – plagues have always come and gone – but, given the uncertainty, it’s smart to build a way of life that is sustainable. We need to anticipate our need for rest. Or be able to support those around us. Take care of our mental and physical health. And we need to feel like our life counts.

Build Spaceship You

In the early months of the pandemic, YouTuber CGP Grey released a video about coping with lockdown and quarantine entitled Spaceship You. The idea was that any kind of shelter in place was a bit like building your own spaceship, then blasting off to survive the crisis alone, in space.

To live well, you have to define the limitations of your space, to clearly delineate the areas where you sleep, work, rest, and exercise, to support your own mental and physical well-being.

CGP Grey had previously explored the danger of creating an “everything space”, where you do all your activity in the same environment (spoiler: it will make you miserable).

It’s tempting to cave into a loungewear, sofa-oriented, “what day of the week is it” routine. But this isn’t some extended semi-holiday. It’s life. By adding some design thinking to the space around us we can navigate our days feeling better and more focussed.

The Future Is Now

There’s a wonderful episode of Veggie Tales (the surprisingly winsome, Christian animated children’s series) which makes fun of the way technology is changing entertainment. IL4 The episode is bizarre – Dada-esque – and its recurring theme is “the future is now.”

I think about that every time I hear NYU professor Scott Galloway rant about how the pandemic has accelerated change in business and society. Galloway likes to use a quote from Lenin about the way change can be sudden at moments like these.

“There are decades where nothing happens, and then there are weeks where decades happen.”

– Vladimir Lenin

From online shopping to work from home and online education, we’re seeing long-held patterns undergo years of change in a matter of weeks. Rather than expecting things to return to some past normal when “all this is over”, we should instead adjust to new realities in the way we work, or shop, or sell the things we make.

Turn Up The Volume

In an interview on the Knowledge Project, Jennifer Garvey Berger suggested the pandemic, especially the experience of lockdown and quarantine, will turn up the volume on the parts of our lives that need to change.

This crisis amplifies discomfort.

It makes clear the decisions you need to make. These could be changes you were already thinking about before the pandemic. Now, it’s impossible to drown out the call. It’s time to change.

This is also true for the voices we listen to and the ones we share with others. It’s a good time to prune our subscriptions, timelines, and inboxes. Make room for people who speak clearly, optimistically, and wisely.

Get To Sleep

Laurie Santos, creator of the Science of Well-Being, posted a great video full of self-care ideas that are supported by scientific evidence. These included exercise, gratitude, being sociable, accepting your emotions, and, of course, sleep.

Stress and anxiety, combined with changes in work and exercise routines, can make sleep harder. But sleep is the core of so many aspects of our health.

I’ve been researching and writing about the intersection of health, creativity, and productivity for five years now, and I’ve repeatedly read how the most solid way to improve your condition starts with getting better sleep. It’s the most reliable foundation for a better mindset, more focus, clarity, and effectiveness throughout the day.

Unknow Yourself

Anyone will tell you 2020 is a horrible dumpster fire of a year. In so many ways, that’s true. But it’s also been true of every previous year for a while – as if that’s the default story now. This year sucks. I can’t wait for it to be over.

The year 2020 has been awful.

But the story we tell about coping can also have some positive aspects.

A surprising example of this is how well many teenagers have fared during quarantine. While this year has been a challenging for many people’s mental health There are examples where the opposite is also true.

The teenagers mentioned in the article have be displayed better than normal mental health, due in part to improved sleep habits, more time with family, and less random social media consumption as recreational habits have switched to planned and intentional time online with friends.

The importance of the story we tell about our life situation is the subject of Lori Gottlieb’s TED Talk. Gottlieb suggests that if we want to live better, we could do with editing the story we tell about ourselves and our circumstances. The story we tell sometimes becomes a trap that limits our growth and our ability to deal with life.

“We talk so much in our culture about getting to know ourselves. But part of getting to know yourself is to unknow yourself. To let go of the one version of the story you’ve been telling yourself, so that you can live your life, and not the story that you’ve been telling yourself about your life.”

– Lori Gottlieb

Summary

These five strands of advice form the best recipe that I’ve found for having a good mindset right now.

Assume this will go on for a long time, design the spaces around you to take care of your physical and mental well-being, pay attention to voices you listen to and the areas of life that urgently need to change, get enough sleep, and be mindful of the story you tell about yourself and about this moment in your life.

The post Advice For Living Well During This Pandemic appeared first on Fernando Gros.

October 7, 2020

Before Planning Begin

He was full of questions. What’s the best software? What filing system should I use? What’s the best format? I’m pretty sure he had more questions than photos. Not an ideal place to be for a budding photographer I thought. But it wasn’t the first time I’d find myself in that sort of conversation, nor would it be the last.

What’s the best music recording software? What’s the best platform for a blog? What’s the best way to sell something online?

The mistake here is putting too much emphasis on planning and not enough on doing. You can’t build the perfect system until you have some sense of what the system is supposed to do.

When To Start By Planning

There’s a famous quote from Cicero: “Before beginning, plan carefully.” You’ve probably seen something similar on a motivational poster or before opening a chapter in a productivity book.

If you’re about to embark on a familiar challenge, it’s a good idea. Study the problem. Gather your tools. Make a plan. Get to work.

But what if “begin” means being a beginner? Or beginning a new kind of challenge?

When Planning Isn’t The Answer

Then, planning carefully could be a trap. You don’t know what’s involved. You don’t know what tools you need. Or what the roadblocks and pitfalls might be. You could easily invest too much time or money on things that end up not mattering.

This is also true for a lot of creative projects.

The shape of the challenge, the thing you are making, will evolve as you make it. I love Twyla Tharp’s suggestion to start each project with a box. When planning a new dance production, she would get a big box, then start putting inspiring things into it – maybe a CD of music or a clipping from a magazine. When it came time to choreograph the piece, she’d dump everything out and make sense of it.

That’s when the planning starts.

Sometimes what we need is to invert Cicero’s idea: “Before planning, begin carefully.”

Begin Then Plan

Take some steps. Try some things. Take some photos. Then start to figure out what software works for you and what catalogue system works. Just buy that paint kit, or take that course, or start banging away at that novel.

When you’re learning how to play, any guitar is better than no guitar.

Eventually, you’ll have something. Then you can start to think about what works for you. You can make informed decisions about tools, processes, and systems.

Then you can make a plan, draw your map, and chart your course.

The post Before Planning Begin appeared first on Fernando Gros.