Anthony McIntyre's Blog, page 1167

January 4, 2018

Brexit Blight

Writing his Ireland Eye Column in Tribune Magazine John Coulter foresees Brexit blight.

Given the almost frantic daily utterances pouring out of Dublin, any Tory-Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) deal with the European Union which does not include a soft border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland could spell economic disaster for the latter.

The DUP may only have 10 MPs at Westminster, but their votes are crucial to keeping the Tories in power and Theresa May herself in Number 10 Downing Street. But the DUP has always been a staunchly Eurosceptic party, and this is one of the main reasons UKIP never took off as a viable movement in Northern Ireland.

There are many Right-wing Unionists in Northern Ireland who view the concept of a so-called hard border as a stick with which to beat the Republic. Then again, Southern Irish politicians lamenting over the lack of a workable deal on Brexit is history repeating itself.

In spite of the global stereotype of the jolly Irish, especially March 17 on St Patrick’s Day when it seems as if everyone tries to claim an Irish heritage, the South of Ireland has been abysmal when it comes to political negotiations.

At the turn of the new millennium, the Republic could boast one of the most vibrant economies, not just in the EU, but right across the world. It was dubbed the Celtic Tiger.

Then the Tiger went bust and needed millions of euros to bail out the nation, with much of it coming from the UK. The Southern economy has crawled back onto its feet again, but now faces the Brexit bombshell – a financial crisis that could drive the Republic economically and politically to the fringes of Europe.

In 2019, when the UK leaves the EU, the Republic will commemorate the centenary of the war of independence with Britain, which led to the setting up of the Free State, the forerunner of the current Republic.

The Republican delegation agreed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which partitioned the island and sparked the bloody Irish Civil War.

Essentially, the English at those talks wiped the floor with the Irish – just as they had done earlier with the Act of Union in the 1800s and the Treaty of Limerick in the 1690s.

The DUP has backed May into a negotiating corner, but joining the Tory Prime Minister in a similar corner is the Republic. While pundits in mainland Britain may be wondering what further concessions the DUP can squeeze out of the Tories in exchange for its support, the real question is what the Republic is prepared to give up in return for a Brexit border that will keep its economy afloat.

Nationalists say that a special status is needed for Northern Ireland, given that it voted ‘remain’ in the referendum. But then other ‘Remain’ regions of the UK – especially Scotland – will also want special status. Go down this path and May’s regional headache becomes the mother of all migraines.

Like the battle cry of the Musketeers, the policy must be all for one and one for all.’ The DUP is demanding that Northern Ireland be treated like every other part of the UK, fearing that special status will signal a united Ireland by the back door. Southern politicians fear they will have to negotiate a new Anglo-Irish Treaty come 2020 because a lack of special status plus a hard border will signal the Republic needing a closer union with the UK to stay afloat financially.

The DUP tail is wagging the Tory dog at Westminster. At what point, then, does May cave in to her party rebels who want her to face down the DUP? Without DUP support, May and her Government will fall and there will be a general election.

If Jeremy Corbyn can restore Labour’s fortunes north of the English border, he may just have enough MPs to give him a slim House of Commons majority. But what are the chances of Corbyn having to rely on DUP MPs to prop up a minority Labour government?

The question then is could Corbyn persuade Sinn Fein MPs to take their seats – especially if a Labour-Sinn Fein coalition could guarantee special status for Northern Ireland?

It’s not the text of a Brexit deal that becomes crucial, but the text of the oath of allegiance to allow Sinn Fein formally into the Commons chamber. Could that be the key challenge?

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist.

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist.

Follow John Coulter on Twitter @JohnAHCoulterDr Coulter is also author of ‘ An Sais Glas: (The Green Sash): The Road to National Republicanism’, which is available on Amazon Kindle.

Given the almost frantic daily utterances pouring out of Dublin, any Tory-Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) deal with the European Union which does not include a soft border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland could spell economic disaster for the latter.

The DUP may only have 10 MPs at Westminster, but their votes are crucial to keeping the Tories in power and Theresa May herself in Number 10 Downing Street. But the DUP has always been a staunchly Eurosceptic party, and this is one of the main reasons UKIP never took off as a viable movement in Northern Ireland.

There are many Right-wing Unionists in Northern Ireland who view the concept of a so-called hard border as a stick with which to beat the Republic. Then again, Southern Irish politicians lamenting over the lack of a workable deal on Brexit is history repeating itself.

In spite of the global stereotype of the jolly Irish, especially March 17 on St Patrick’s Day when it seems as if everyone tries to claim an Irish heritage, the South of Ireland has been abysmal when it comes to political negotiations.

At the turn of the new millennium, the Republic could boast one of the most vibrant economies, not just in the EU, but right across the world. It was dubbed the Celtic Tiger.

Then the Tiger went bust and needed millions of euros to bail out the nation, with much of it coming from the UK. The Southern economy has crawled back onto its feet again, but now faces the Brexit bombshell – a financial crisis that could drive the Republic economically and politically to the fringes of Europe.

In 2019, when the UK leaves the EU, the Republic will commemorate the centenary of the war of independence with Britain, which led to the setting up of the Free State, the forerunner of the current Republic.

The Republican delegation agreed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which partitioned the island and sparked the bloody Irish Civil War.

Essentially, the English at those talks wiped the floor with the Irish – just as they had done earlier with the Act of Union in the 1800s and the Treaty of Limerick in the 1690s.

The DUP has backed May into a negotiating corner, but joining the Tory Prime Minister in a similar corner is the Republic. While pundits in mainland Britain may be wondering what further concessions the DUP can squeeze out of the Tories in exchange for its support, the real question is what the Republic is prepared to give up in return for a Brexit border that will keep its economy afloat.

Nationalists say that a special status is needed for Northern Ireland, given that it voted ‘remain’ in the referendum. But then other ‘Remain’ regions of the UK – especially Scotland – will also want special status. Go down this path and May’s regional headache becomes the mother of all migraines.

Like the battle cry of the Musketeers, the policy must be all for one and one for all.’ The DUP is demanding that Northern Ireland be treated like every other part of the UK, fearing that special status will signal a united Ireland by the back door. Southern politicians fear they will have to negotiate a new Anglo-Irish Treaty come 2020 because a lack of special status plus a hard border will signal the Republic needing a closer union with the UK to stay afloat financially.

The DUP tail is wagging the Tory dog at Westminster. At what point, then, does May cave in to her party rebels who want her to face down the DUP? Without DUP support, May and her Government will fall and there will be a general election.

If Jeremy Corbyn can restore Labour’s fortunes north of the English border, he may just have enough MPs to give him a slim House of Commons majority. But what are the chances of Corbyn having to rely on DUP MPs to prop up a minority Labour government?

The question then is could Corbyn persuade Sinn Fein MPs to take their seats – especially if a Labour-Sinn Fein coalition could guarantee special status for Northern Ireland?

It’s not the text of a Brexit deal that becomes crucial, but the text of the oath of allegiance to allow Sinn Fein formally into the Commons chamber. Could that be the key challenge?

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist.

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist. Follow John Coulter on Twitter @JohnAHCoulterDr Coulter is also author of ‘ An Sais Glas: (The Green Sash): The Road to National Republicanism’, which is available on Amazon Kindle.

Published on January 04, 2018 00:00

January 3, 2018

Technologies That Multiply Inequalities

Gabriel Levy reviews The Bleeding Edge: why technology turns toxic in an unequal world by Bob Hughes (Oxford: New Internationalist, 2016)

How is it that the internet – a technology with such powerful, democratic potential – hovers over us like a monster that intrudes and spies, interferes in our collective interactions and thought processes, force-feeds us corporate garbage and imposes new work disciplines? What happened?

Bob Hughes, by thinking both about how computers work and how society works, offers compelling insights about these and other questions.

One of Hughes’s riffs on technological themes starts with the Forbes web page about Marc Andreessen, one of the world’s richest men, who in 1994 released the first version of the Netscape Navigator browser. Microsoft distributed Netscape with the Windows operating system, making Andreessen an instant multi-millionaire.

picture of demo: by Rainer Jensen/AP.

picture of demo: by Rainer Jensen/AP.

When Hughes visited the page, he found 196 words of information about Andreessen (last week, when I looked, there were only 81). Hughes found (and so did I) about another 1000 words of promotional and advertising material.

Behind those words lay a HTML page with 8506 words, or 88,928 characters. The promotional material multiplied the capacity required by the page 88 times – and that was not including the graphics. Including these, the page took about three-quarters of a megabyte of memory.

In the mid 1990s, Netscape Navigator made such advertising displays easy. It allowed web pages to create “cookies” on users’ machines to monitor the information that they enter, and enabled them to record and monitor information used in commerce. It effectively buried the principle, with which Tim Berners-Lee and other founders of the internet began, that the system would base itself on a huge mountain of identifiable text-only documents.

Hughes describes how Netscape Navigator and other developments opened the way for the dotcom bubble on the world’s stock exchanges, in 1997-2000, and a new technological leap, Web 2.0. This made possible live search functions, interactive social media, and the proliferation of online auction, booking, commercial and banking sites.

The interactivity of the modern web is linked with an obsession among those who control it with speed – the computer-crunching power that allows pages to be updated and re-rendered instantaneously.

The crunching-power required has in the last 15 years turned the internet – which is often thought of as a relatively resource-light technology – into a massive user of electricity. Humungous data centres are built in parts of the USA where their owners cut special deals for bulk purchase with the local power companies. (See New York Times report here.)

Greenpeace has published estimates of the data centres’ electricity demand, compiled in the teeth of the internet companies’ maniacal secrecy, ranging from 263 billion kwh/year (including 76 billion kwh in the USA) for data centres only, to 372 billion kwh/year for data centres and telecoms infrastructure. (Another good article here.)

Consumption by the whole “cloud”, including manufacture and use of devices, has been estimated at 623 billion kwh/year. That’s more than the national total consumption of all countries except the USA, Russia, Japan and China. More than the total consumption for all purposes by India.

Hughes discusses all this and more. He argues that a society as unequal as capitalism constantly strangles and misdirects technological potential, instead of developing it.

Hughes points to ways that things could have gone, had it not been for the corporations’ grip – which was tightened not in the first stages of internet development, when the military and optimistic amateurs, by turns, pushed things forward, but later. There is a lengthy passage on the possibilities of analog computer technology, left unrealised as digital, and its corporate controllers, gained precedence.

The Moniac computer in the Science Museum in London (see “About the picture of Moniac”, below)

The Moniac computer in the Science Museum in London (see “About the picture of Moniac”, below)

In a section on the incredible, and largely planned, obsolescence of computers, he writes:

Such an attitude would always have struggled to thrive in a society that has “turned inter-personal rivalry into a cardinal virtue”, Hughes argues.

Hughes is attentive to the way that inequality not only provides the context for technology, but pervades the industry itself. Workers at the Foxconn factories in China, where there was a large number of suicides in 2010, were paid $130 per month, about one 31,000th of the salary of Apple’s then CEO, the late Steve Jobs, who was on $48 million a year.

“The inequality embodied in something like an iPhone could not be more different from the egalitarianism that made it possible, but it is not without precedent” (p. 57). Those precedents go at least as far back as the technological developments in the 16th century textile industry that enabled employers to wreck skilled labour systems and impoverish those that depended on them.

Hughes is no technophobe. The point he hammers home again and again is that technologies – and his examples are not only from computing history but from e.g. materials manufacture and road transport – take the directions they do because of the way society works. His emphasis is on inequality. At times it was unclear to me how, except by going past capitalist property relations, he thought that that would be overcome.

Nevertheless, I found Hughes’s approach a refreshing antidote to the one-sided technological determinism of writers associated with the “left” such as Paul Mason, in Post-Capitalism (see my review here) and Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, in Inventing the Future (see my comments here).

Hughes writes with knowledge, and feeling, about the egalitarian and liberatory potential of computers and other technology. He considers voices in technology that challenged its social role such as Norbert Wiener and Stafford Beer, both pioneers of cybernetics. He has a fascinating chapter on Cybersyn, the cybernetics programme used by Salvador Allende’s government in Chile – on which Beer, who was British, worked – before it was overthrown in the bloody CIA-backed military coup of September 1973. (See an article by Eden Medina here and another one here.)

Stafford Beer

Stafford Beer

I warmed to Hughes’s optimism. In his final chapter, he argues that we need to “take the whole notion of Utopia more seriously”. In a more equal world, “jobs would serve community needs rather than profit, caring roles would be a priority and automation would encourage skilled work rather than eliminate it. But to arrive there we will need to undermine the ‘apparatus of justification’ on which inequality depends” (p. 303). The Bleeding Edge is a fine contribution to a serious conversation about technology and radical social change. GL, 5 December 2017.

About the picture of Moniac (the Monetary National Income Automatic Computer). Moniac was built in 1949 by Bill Phillips, a New Zealand economist, and is now displayed in the Science Museum in London. Hughes writes: “Phillips had realised that the mathematical models John Maynard Keynes and Joan Robinson had used to describe economic systems were very similar to ones used in hydraulics. […] His computer modelled the flows of cash, credit, savings and investments in an economy with a system of plastic tubes, reservoirs, pumps and valves. […] MONIACs were used in teaching and in research at the London School of Economics and several other institutions until Keynesian economics went out of fashion in the 1970s” (pp. 232-233). This is an example of analog computing, which physically models systems you are trying to control or examine, and which has since died out.

Note (21.12.17). This article has been corrected, to say that Stafford Beer was British, not American.

Gabriel Levy blogs @ People and Nature

How is it that the internet – a technology with such powerful, democratic potential – hovers over us like a monster that intrudes and spies, interferes in our collective interactions and thought processes, force-feeds us corporate garbage and imposes new work disciplines? What happened?

Bob Hughes, by thinking both about how computers work and how society works, offers compelling insights about these and other questions.

One of Hughes’s riffs on technological themes starts with the Forbes web page about Marc Andreessen, one of the world’s richest men, who in 1994 released the first version of the Netscape Navigator browser. Microsoft distributed Netscape with the Windows operating system, making Andreessen an instant multi-millionaire.

picture of demo: by Rainer Jensen/AP.

picture of demo: by Rainer Jensen/AP.

When Hughes visited the page, he found 196 words of information about Andreessen (last week, when I looked, there were only 81). Hughes found (and so did I) about another 1000 words of promotional and advertising material.

Behind those words lay a HTML page with 8506 words, or 88,928 characters. The promotional material multiplied the capacity required by the page 88 times – and that was not including the graphics. Including these, the page took about three-quarters of a megabyte of memory.

In the mid 1990s, Netscape Navigator made such advertising displays easy. It allowed web pages to create “cookies” on users’ machines to monitor the information that they enter, and enabled them to record and monitor information used in commerce. It effectively buried the principle, with which Tim Berners-Lee and other founders of the internet began, that the system would base itself on a huge mountain of identifiable text-only documents.

Hughes describes how Netscape Navigator and other developments opened the way for the dotcom bubble on the world’s stock exchanges, in 1997-2000, and a new technological leap, Web 2.0. This made possible live search functions, interactive social media, and the proliferation of online auction, booking, commercial and banking sites.

Web 2.0 was created under pressure from increasingly powerful e-business interests, against principled resistance from the World Wide Web Consortium, whose founding principles included a commitment to making the Web accessible to all, including the visually handicapped and the blind, and in as many different ways as possible - Hughes writes (p. 226).

The interactivity of the modern web is linked with an obsession among those who control it with speed – the computer-crunching power that allows pages to be updated and re-rendered instantaneously.

The crunching-power required has in the last 15 years turned the internet – which is often thought of as a relatively resource-light technology – into a massive user of electricity. Humungous data centres are built in parts of the USA where their owners cut special deals for bulk purchase with the local power companies. (See New York Times report here.)

Greenpeace has published estimates of the data centres’ electricity demand, compiled in the teeth of the internet companies’ maniacal secrecy, ranging from 263 billion kwh/year (including 76 billion kwh in the USA) for data centres only, to 372 billion kwh/year for data centres and telecoms infrastructure. (Another good article here.)

Consumption by the whole “cloud”, including manufacture and use of devices, has been estimated at 623 billion kwh/year. That’s more than the national total consumption of all countries except the USA, Russia, Japan and China. More than the total consumption for all purposes by India.

Hughes discusses all this and more. He argues that a society as unequal as capitalism constantly strangles and misdirects technological potential, instead of developing it.

Hughes points to ways that things could have gone, had it not been for the corporations’ grip – which was tightened not in the first stages of internet development, when the military and optimistic amateurs, by turns, pushed things forward, but later. There is a lengthy passage on the possibilities of analog computer technology, left unrealised as digital, and its corporate controllers, gained precedence.

The Moniac computer in the Science Museum in London (see “About the picture of Moniac”, below)

The Moniac computer in the Science Museum in London (see “About the picture of Moniac”, below)In a section on the incredible, and largely planned, obsolescence of computers, he writes:

“Computers could be used to increase the size of the ‘economic pie’ for everyone while reducing human environmental impact. This was the confident expectation in the 1970s – but it would have required a large-scale determined commitment to mutuality that failed to develop” (p. 133).

Such an attitude would always have struggled to thrive in a society that has “turned inter-personal rivalry into a cardinal virtue”, Hughes argues.

Hughes is attentive to the way that inequality not only provides the context for technology, but pervades the industry itself. Workers at the Foxconn factories in China, where there was a large number of suicides in 2010, were paid $130 per month, about one 31,000th of the salary of Apple’s then CEO, the late Steve Jobs, who was on $48 million a year.

“The inequality embodied in something like an iPhone could not be more different from the egalitarianism that made it possible, but it is not without precedent” (p. 57). Those precedents go at least as far back as the technological developments in the 16th century textile industry that enabled employers to wreck skilled labour systems and impoverish those that depended on them.

Hughes is no technophobe. The point he hammers home again and again is that technologies – and his examples are not only from computing history but from e.g. materials manufacture and road transport – take the directions they do because of the way society works. His emphasis is on inequality. At times it was unclear to me how, except by going past capitalist property relations, he thought that that would be overcome.

Nevertheless, I found Hughes’s approach a refreshing antidote to the one-sided technological determinism of writers associated with the “left” such as Paul Mason, in Post-Capitalism (see my review here) and Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, in Inventing the Future (see my comments here).

Hughes writes with knowledge, and feeling, about the egalitarian and liberatory potential of computers and other technology. He considers voices in technology that challenged its social role such as Norbert Wiener and Stafford Beer, both pioneers of cybernetics. He has a fascinating chapter on Cybersyn, the cybernetics programme used by Salvador Allende’s government in Chile – on which Beer, who was British, worked – before it was overthrown in the bloody CIA-backed military coup of September 1973. (See an article by Eden Medina here and another one here.)

Stafford Beer

Stafford BeerI warmed to Hughes’s optimism. In his final chapter, he argues that we need to “take the whole notion of Utopia more seriously”. In a more equal world, “jobs would serve community needs rather than profit, caring roles would be a priority and automation would encourage skilled work rather than eliminate it. But to arrive there we will need to undermine the ‘apparatus of justification’ on which inequality depends” (p. 303). The Bleeding Edge is a fine contribution to a serious conversation about technology and radical social change. GL, 5 December 2017.

About the picture of Moniac (the Monetary National Income Automatic Computer). Moniac was built in 1949 by Bill Phillips, a New Zealand economist, and is now displayed in the Science Museum in London. Hughes writes: “Phillips had realised that the mathematical models John Maynard Keynes and Joan Robinson had used to describe economic systems were very similar to ones used in hydraulics. […] His computer modelled the flows of cash, credit, savings and investments in an economy with a system of plastic tubes, reservoirs, pumps and valves. […] MONIACs were used in teaching and in research at the London School of Economics and several other institutions until Keynesian economics went out of fashion in the 1970s” (pp. 232-233). This is an example of analog computing, which physically models systems you are trying to control or examine, and which has since died out.

Note (21.12.17). This article has been corrected, to say that Stafford Beer was British, not American.

Gabriel Levy blogs @ People and Nature

Published on January 03, 2018 12:00

Book Launch: Michael Ryan's Life In The IRA

Published on January 03, 2018 03:03

January 2, 2018

Rebecca

A poignant reflection from Sean Mallory on the death of a friend’s sister.

Prior to the result, I had just entered my local pub after gaining a free pass-out for all my chores around the house earlier that day and was sitting chatting and sipping a pint, happy as a pig in the proverbial. Shortly before the game started I received a message from an old friend. A very old friend, not old in reference to his age, but in reference to our friendship. We don’t see each other a great deal, in fact about only once in the last 10 years but nevertheless, a friendship that once kindled it is hard to blow out.

His message wasn’t about the game or football or even a quick hello but to let me know that his sister, Rebecca, had taken her own life earlier that day. She was around the same age of my own sister who died of a cancer related illness recently. Having experienced the loss of my own sister my heart sank on reading his text message. But suicide is different and the ‘what ifs’ are much more poignant in that they can never be answered.

Cancer is a diagnosis with the unfortunate recipient being present. Family, relatives and friends can gather round an offer succour and comfort. There is a prognosis, rarely benign and more commonly malignant, but a prognosis on a way forward to stave of the eventual terminal effect of it. A path that offers hope, perhaps false hope, and provides answers to difficult questions. A path that doesn’t throw up horrible surprises but only the inevitable, no matter how painful. But it's never immediate.

Suicide, on the other hand offers none of the above and it is immediate. Like cancer though, it is horrible and extremely unwelcome news to receive. It can break families apart, gradually wear them down and leave them no answer to the numerous ‘whys’.

What it has become in this materialistic and commodity driven society is much more common and frequent. It is very rarely something decided and acted upon in an instant with the obvious exceptions being substance overdoses by addicts.

From my own experience of having lost people, some very good friends and some work acquaintances, it tends to be a resolution determined by the individual, suffering from severe mental anguish, as the only alternative path to their predicament.

As we are generally not psychiatrists nor psychologists, and as most times engrossed in our own lives, we fail to spot the signs. There is no blame to lay at the door of the living and no blame to lay at the deceased, for the turmoil they unconsciously leave behind.

Mourn them as you would mourn a sister who died of cancer, for irrespective of how they met their untimely demise you’ll miss them dearly.

So sorry for your loss.

Sean Mallory is a TPQ columnist

Published on January 02, 2018 11:00

Zaghari-Ratcliffe And The Tale Of Unpaid British Debt

Left wing blogger Mick Hall asks:

Has Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe been held in an Iranian prison because the British government refuses to pay it's debts?

Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe with her family in happier times.

The truth is slowly emerging as to why the Iranian government is taking a strong line over the imprisonment of Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the British-Iranian charity worker and mother of one, who was arrested in Iran last April and has been held in detention since.

She and her husband have long believed she may be viewed as collateral by the government in Tehran. We now know why and it is no thanks to the British government but due to the persistence of her husband.

The history of this sorry saga began in the mid-1970s when the Shah of Iran’s regime was one of the British defence industry’s major cash cows. The vainglorious Shah was spending hundreds of millions of dollars on tanks, missiles and military infrastructure his people could ill afford.

On the eve of the Islamic Revolution in 1979 the Shah’s armed forces already equipped with 250 Scorpion reconnaissance tanks and 760 Chieftain battle tanks placed another order for 1,200 tanks.

A deal had also been signed to build a military industrial manufacturing complex at Ishafan, 200 miles south of Tehran, where Iran planned to develop its own arms industry.

Delivery of the second tranche of Chieftain tanks had barely begun when the Shah was ousted and the new revolutionary government of Iran which had replaced the Shah pulled out of the deal, understandably demanding the British government return its money.

The demand was made to Millbank Technical Services, an agency fully owned by the Ministry of Defence. The government refused Iran’s demands, setting in motion a legal case that has rumbled on for years.

In other words the British government refused to pay Iran what it was owed under the clauses in the contract.

In 2001 an international arbitration tribunal in The Hague ruled in favour of Iran and said the company, now renamed International Military Services, should repay Iran the money it was owed with damages and interest.

The Dutch courts upheld that ruling. Some £500 million to settle the debt has been paid into the High Court and is frozen pending an agreement.

The British government stalled and refused to pay its debt.

Boris Johnson would have known all this yet failed to act, instead sending a smokescreen down about Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe teaching Iranian journalists to suck eggs.

According to The Times a British government spokesperson put out a sorry excuse for welching on a debt:

Talk about the doublespeak of a conman, and a heartless one at that, for I doubt Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe and her family would believe the pressure is on Iran. Besides the legality of the debt has already been decided, not once but twice, first by the international arbitration tribunal in The Hague when it ruled in favour of Iran, secondly by Dutch courts when they upheld that ruling.

Is it any wonder Britain has become a laughing stock in the world when its government refuse to pay its debts and to justify it acts like a poor imitation of a flimflam man.

➤Information in this post provided by Sean O’Neill.

Mick Hall blogs @ Organized Rage.

Mick Hall blogs @ Organized Rage.

Follow Mick Hall on Twitter @organizedrage

Has Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe been held in an Iranian prison because the British government refuses to pay it's debts?

Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe with her family in happier times.

The truth is slowly emerging as to why the Iranian government is taking a strong line over the imprisonment of Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the British-Iranian charity worker and mother of one, who was arrested in Iran last April and has been held in detention since.

She and her husband have long believed she may be viewed as collateral by the government in Tehran. We now know why and it is no thanks to the British government but due to the persistence of her husband.

The history of this sorry saga began in the mid-1970s when the Shah of Iran’s regime was one of the British defence industry’s major cash cows. The vainglorious Shah was spending hundreds of millions of dollars on tanks, missiles and military infrastructure his people could ill afford.

On the eve of the Islamic Revolution in 1979 the Shah’s armed forces already equipped with 250 Scorpion reconnaissance tanks and 760 Chieftain battle tanks placed another order for 1,200 tanks.

A deal had also been signed to build a military industrial manufacturing complex at Ishafan, 200 miles south of Tehran, where Iran planned to develop its own arms industry.

Delivery of the second tranche of Chieftain tanks had barely begun when the Shah was ousted and the new revolutionary government of Iran which had replaced the Shah pulled out of the deal, understandably demanding the British government return its money.

The demand was made to Millbank Technical Services, an agency fully owned by the Ministry of Defence. The government refused Iran’s demands, setting in motion a legal case that has rumbled on for years.

In other words the British government refused to pay Iran what it was owed under the clauses in the contract.

In 2001 an international arbitration tribunal in The Hague ruled in favour of Iran and said the company, now renamed International Military Services, should repay Iran the money it was owed with damages and interest.

The Dutch courts upheld that ruling. Some £500 million to settle the debt has been paid into the High Court and is frozen pending an agreement.

The British government stalled and refused to pay its debt.

Boris Johnson would have known all this yet failed to act, instead sending a smokescreen down about Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe teaching Iranian journalists to suck eggs.

According to The Times a British government spokesperson put out a sorry excuse for welching on a debt:

It’s really not for the UK to make the move. The ball is in Iran’s court to show the money goes to the right place. That’s the point at which we can consider the legality. [But] that barrier of proof has not been in any way met . . . The pressure is on Iran.

Talk about the doublespeak of a conman, and a heartless one at that, for I doubt Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe and her family would believe the pressure is on Iran. Besides the legality of the debt has already been decided, not once but twice, first by the international arbitration tribunal in The Hague when it ruled in favour of Iran, secondly by Dutch courts when they upheld that ruling.

Is it any wonder Britain has become a laughing stock in the world when its government refuse to pay its debts and to justify it acts like a poor imitation of a flimflam man.

➤Information in this post provided by Sean O’Neill.

Mick Hall blogs @ Organized Rage.

Mick Hall blogs @ Organized Rage.Follow Mick Hall on Twitter @organizedrage

Published on January 02, 2018 04:00

January 1, 2018

Victor Notarantonio

Anthony McIntyre looks back on his friendship with Victor Notarantonio who died last January.

I came to know him through his son Crick, a friend of mine. Then he and I established a friendship in its own right. I would often visit his home, talk shop, chat with his wife, Kate, drink spirits or watch the soccer on his widescreen television, the first I had come cross in anybody’s home. It led to me to acquiring one myself which took years to pay off. Thing is – I wouldn’t go for a small screen again, and haven’t been without a big screen since. The sport and wild life in high definition big screen are something else.

We often talked politics and at the time of the Good Friday Agreement he bantered me about siding with the DUP by voting against it. I pointed out the UDA which had killed his father was supporting it, so if I was on the same side as the DUP he was on the same side as the UDA. He laughed but appreciated the irony I had drawn his attention to, even though neither of us was too serious about the matter. Political choices are more complex than the Manichean allows for.

Vic had a very laid back manner, which took verbal expression in the form of a drawl. He never got excitable over much. Frequently we would share a brandy in his home. On one occasion when I asked for ginger he dismissed the request with the retort that it cost seventy five quid a bottle so I would have to drink it straight and not ruin it with ginger. There is some wisdom in that but whiskey is easier taken neat than brandy.

The Notarantonio family had a history of association with republicanism. Victor's father, a former republican internee was shot dead in 1987 in a British dirty tricks operation. The British directed the UDA to kill him in order to divert the loyalist group away from one of the military’s informers. Victor and his brother Christopher, had both been internees, Vic at one time being held on the Maidstone prison ship, in Belfast Lough.

He was deeply hurt by the October 2000 Provisional IRA killing of his nephew, Joe O’Connor, in the same street where the British and UDA had slain his father. He further felt insulted by the organisation's denial of responsibility and cynical offer of sympathy to the family. Victor firmly believed felt he had negotiated a peaceful resolution to conflict between the Real and Provisional IRAs in Ballymurphy, only to be shafted down the line. Victor told the press, "I never thought the day would come when it would be the Provos killing us."

The extended Notarantonio family were the target of a fire bomb campaign in the wake of the 2006 killing of Gerard Devlin. While it was easy for many to lay the blame at the door of relatives and friends of "Dev," infuriated at the death of their loved one at the hands of one of Victor’s sons, much of the burning was orchestrated by the Provisionals in a score settling exercise. Although he had great relations with many in the Provos Victor always felt there was an underlying tension with key leadership elements because of a belief on their part that he had been the IRA volunteer responsible for kneecapping a brother of Gerry Adams back in the 1970s. Many times, when I was in the home prior to the killing of his nephew Joe O’Connor, Provisionals would call to see Victor and were undoubtedly friendly with him. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that he was in some way linked to the financial side of the organisation. He specialised in the acquisition and distribution of cigarettes.

At one point he went down to see the late Denis Donaldson in his remote cottage in Glenties, Donegal. He explained to me his reasoning behind the trip, feeling that the British agent might be able to provide him with some understanding of why there was such animosity from leadership towards his wider family circle.

That there was a volley of shots fired over his coffin suggests that if he was not a volunteer with one of the many republican groups that populate the nationalist political landscape, at the time of his death, he was held in high esteem by many from that quarter.

I found him a great friend. The last time we met was by chance in Dundalk, where he was shopping in the main street with his wife Kate. In the days before he died I tried ringing the house as he was expecting a call from me but the phone was permanently engaged, so many wanted to share a few last words with him.

The chance for a final spoken exchange might have been missed but the opportunity to remember him in written form was not something I was prepared to forsake.

Slan Vic.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Follow Anthony McIntyre on Twitter @AnthonyMcIntyre

I came to know him through his son Crick, a friend of mine. Then he and I established a friendship in its own right. I would often visit his home, talk shop, chat with his wife, Kate, drink spirits or watch the soccer on his widescreen television, the first I had come cross in anybody’s home. It led to me to acquiring one myself which took years to pay off. Thing is – I wouldn’t go for a small screen again, and haven’t been without a big screen since. The sport and wild life in high definition big screen are something else.

We often talked politics and at the time of the Good Friday Agreement he bantered me about siding with the DUP by voting against it. I pointed out the UDA which had killed his father was supporting it, so if I was on the same side as the DUP he was on the same side as the UDA. He laughed but appreciated the irony I had drawn his attention to, even though neither of us was too serious about the matter. Political choices are more complex than the Manichean allows for.

Vic had a very laid back manner, which took verbal expression in the form of a drawl. He never got excitable over much. Frequently we would share a brandy in his home. On one occasion when I asked for ginger he dismissed the request with the retort that it cost seventy five quid a bottle so I would have to drink it straight and not ruin it with ginger. There is some wisdom in that but whiskey is easier taken neat than brandy.

The Notarantonio family had a history of association with republicanism. Victor's father, a former republican internee was shot dead in 1987 in a British dirty tricks operation. The British directed the UDA to kill him in order to divert the loyalist group away from one of the military’s informers. Victor and his brother Christopher, had both been internees, Vic at one time being held on the Maidstone prison ship, in Belfast Lough.

He was deeply hurt by the October 2000 Provisional IRA killing of his nephew, Joe O’Connor, in the same street where the British and UDA had slain his father. He further felt insulted by the organisation's denial of responsibility and cynical offer of sympathy to the family. Victor firmly believed felt he had negotiated a peaceful resolution to conflict between the Real and Provisional IRAs in Ballymurphy, only to be shafted down the line. Victor told the press, "I never thought the day would come when it would be the Provos killing us."

The extended Notarantonio family were the target of a fire bomb campaign in the wake of the 2006 killing of Gerard Devlin. While it was easy for many to lay the blame at the door of relatives and friends of "Dev," infuriated at the death of their loved one at the hands of one of Victor’s sons, much of the burning was orchestrated by the Provisionals in a score settling exercise. Although he had great relations with many in the Provos Victor always felt there was an underlying tension with key leadership elements because of a belief on their part that he had been the IRA volunteer responsible for kneecapping a brother of Gerry Adams back in the 1970s. Many times, when I was in the home prior to the killing of his nephew Joe O’Connor, Provisionals would call to see Victor and were undoubtedly friendly with him. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that he was in some way linked to the financial side of the organisation. He specialised in the acquisition and distribution of cigarettes.

At one point he went down to see the late Denis Donaldson in his remote cottage in Glenties, Donegal. He explained to me his reasoning behind the trip, feeling that the British agent might be able to provide him with some understanding of why there was such animosity from leadership towards his wider family circle.

That there was a volley of shots fired over his coffin suggests that if he was not a volunteer with one of the many republican groups that populate the nationalist political landscape, at the time of his death, he was held in high esteem by many from that quarter.

I found him a great friend. The last time we met was by chance in Dundalk, where he was shopping in the main street with his wife Kate. In the days before he died I tried ringing the house as he was expecting a call from me but the phone was permanently engaged, so many wanted to share a few last words with him.

The chance for a final spoken exchange might have been missed but the opportunity to remember him in written form was not something I was prepared to forsake.

Slan Vic.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.Follow Anthony McIntyre on Twitter @AnthonyMcIntyre

Published on January 01, 2018 13:26

Go Head-To-Head With Germany

Form a new European Economic Community based solely on trade; that’s the suggestion of John Coulter as he opens up TPQ's account in the New Year. That's his advice for the British Prime Minister and Republic’s Taoiseach as the next phase of the trade talks heralding the UK’s divorce from the failing European Union shifts into top gear in 2018. In his latest Fearless Flying Column today, controversial commentator Dr John Coulter, propose an EEC Mark 2 comprising nine nations.

The German dream of European domination is now is tatters with Brexit, and the trade talks must head in only one workable solution – the creation of a new European Economic Community (EEC) based entirely on trading relations. The old EEC worked when the modern day EU is failing.

The United Kingdom has sparked a new political revolution across Europe which has the potential to take at least eight other current EU nation states into a new EEC.

Already there are rumblings in Poland – supported by Hungary – against EU diktats. Perhaps the only way Spain can resolve the Catalonian crisis and remain as a united nation is to follow the UK out of the EU.

With the emergence of the Far Right in Austria once again, serious questions will be asked about that nation’s future in the EU. Add in Ireland (cleared worried about the Brexit Bounce on its economy), and other states with strong Euro skeptic communities, such as Denmark, Italy and Greece and you have the basis of the EEC Mark 2.

During this year’s trade talks about UK withdrawal from the EU, all eyes will obviously be focussed on the reaction of the Germans. For Germany, history plays a major role.

It is very clear the Germans have never forgotten the crushing defeat which French Emperor Napoleon inflicted on Prussia in the 1806/07 War of the Fourth Coalition, which saw the French march proudly into Berlin.

It was equally clear the Prussians had learned nothing from Napoleon’s equally serious defeat of the combined Russian and Austrian forces at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, which paved the way for the French march on Berlin.

Twice in the first half of the 20th century, Germany has tried to rule Europe by military means. Kaiser Bill failed in 1918 and Hitler was defeated in 1945 with both wars costing millions of lives.

But with the fall of the Berlin wall and the reunification of the country, Germany was once more in a position to challenge for the position of top dog in Europe. But this time, there would be no tanks or planes – it would be purely economic.

The 2018 trade talks are not so much about how much the UK will have to pay the EU to guarantee its economic divorce, but are more about how much control can Germany have on its EU partners.

The other major factor which the current German government seems incapable of coming to terms with is the steady growth of the populist Far Right across many EU states, based on the concept of reclaiming national sovereignty. The rise of the Hard Right AfD party in Germany alone has proven that the fascist fox is once more in the moderate chicken coup!

Germany cannot even rely too much on neighbour France given the Far Right Front National’s continued strength. Throw in the Freedom Party in Austria, Golden Dawn in Greece and Jobbik in Hungary and the German economic blanket which once covered virtually all of the EU is starting to rapidly unravel at the seams.

Assuming British Prime Minister Theresa May’s minority Conservative Government survives with the help of the DUP MPs until at least Brexit in March 2019, how should the embattled Tory PM play the trade talks?

The tactic must be ‘divide and conquer’ rather than ‘we’ll go it alone’. She must fuel the ethos of Euro scepticism throughout the so-called ‘Gang of Nine’ nations under the strategy – one oorut, eight still to follow. Yes, in a worst case scenario, the UK may have to pay huge economic ‘reparations’ for daring to follow the democratic wishes of its citizens in a referendum and walk away from the EU. True, other nations – particularly within the Gang of Nine – which boast a strong Euro skeptic tradition may be also privately pondering their economic future within the EU, but are equally wondering what the financial bill will be for quitting the EU.

If the pro-German Europhiles have their way, the EU will make an economic example out of the UK by making the UK pay such a heavy financial divorce that other unofficial members of the Gang of Nine will be too afraid to leave.

However, if May and her colleagues – especially if she can allow MPs from the staunchly Euro skeptic DUP to be part of those trade talks – can play the strategy of ‘united we stand and we can all get out of the EU’, then the foundation of a new EEC will become a reality.

It’s not so much a question of ‘how much will we have to pay?’ but ‘how much can we pull the financial rug from under Germany’s feet’ which will be the key factor in 2018. Supplementary question – does the Tory/DUP coalition have the Maggie Thatcher-style courage to go head-to-head with Germany?

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist.

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist.

Follow John Coulter on Twitter @JohnAHCoulterDr Coulter is also author of ‘ An Sais Glas: (The Green Sash): The Road to National Republicanism’, which is available on Amazon Kindle.

The German dream of European domination is now is tatters with Brexit, and the trade talks must head in only one workable solution – the creation of a new European Economic Community (EEC) based entirely on trading relations. The old EEC worked when the modern day EU is failing.

The United Kingdom has sparked a new political revolution across Europe which has the potential to take at least eight other current EU nation states into a new EEC.

Already there are rumblings in Poland – supported by Hungary – against EU diktats. Perhaps the only way Spain can resolve the Catalonian crisis and remain as a united nation is to follow the UK out of the EU.

With the emergence of the Far Right in Austria once again, serious questions will be asked about that nation’s future in the EU. Add in Ireland (cleared worried about the Brexit Bounce on its economy), and other states with strong Euro skeptic communities, such as Denmark, Italy and Greece and you have the basis of the EEC Mark 2.

During this year’s trade talks about UK withdrawal from the EU, all eyes will obviously be focussed on the reaction of the Germans. For Germany, history plays a major role.

It is very clear the Germans have never forgotten the crushing defeat which French Emperor Napoleon inflicted on Prussia in the 1806/07 War of the Fourth Coalition, which saw the French march proudly into Berlin.

It was equally clear the Prussians had learned nothing from Napoleon’s equally serious defeat of the combined Russian and Austrian forces at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, which paved the way for the French march on Berlin.

Twice in the first half of the 20th century, Germany has tried to rule Europe by military means. Kaiser Bill failed in 1918 and Hitler was defeated in 1945 with both wars costing millions of lives.

But with the fall of the Berlin wall and the reunification of the country, Germany was once more in a position to challenge for the position of top dog in Europe. But this time, there would be no tanks or planes – it would be purely economic.

The 2018 trade talks are not so much about how much the UK will have to pay the EU to guarantee its economic divorce, but are more about how much control can Germany have on its EU partners.

The other major factor which the current German government seems incapable of coming to terms with is the steady growth of the populist Far Right across many EU states, based on the concept of reclaiming national sovereignty. The rise of the Hard Right AfD party in Germany alone has proven that the fascist fox is once more in the moderate chicken coup!

Germany cannot even rely too much on neighbour France given the Far Right Front National’s continued strength. Throw in the Freedom Party in Austria, Golden Dawn in Greece and Jobbik in Hungary and the German economic blanket which once covered virtually all of the EU is starting to rapidly unravel at the seams.

Assuming British Prime Minister Theresa May’s minority Conservative Government survives with the help of the DUP MPs until at least Brexit in March 2019, how should the embattled Tory PM play the trade talks?

The tactic must be ‘divide and conquer’ rather than ‘we’ll go it alone’. She must fuel the ethos of Euro scepticism throughout the so-called ‘Gang of Nine’ nations under the strategy – one oorut, eight still to follow. Yes, in a worst case scenario, the UK may have to pay huge economic ‘reparations’ for daring to follow the democratic wishes of its citizens in a referendum and walk away from the EU. True, other nations – particularly within the Gang of Nine – which boast a strong Euro skeptic tradition may be also privately pondering their economic future within the EU, but are equally wondering what the financial bill will be for quitting the EU.

If the pro-German Europhiles have their way, the EU will make an economic example out of the UK by making the UK pay such a heavy financial divorce that other unofficial members of the Gang of Nine will be too afraid to leave.

However, if May and her colleagues – especially if she can allow MPs from the staunchly Euro skeptic DUP to be part of those trade talks – can play the strategy of ‘united we stand and we can all get out of the EU’, then the foundation of a new EEC will become a reality.

It’s not so much a question of ‘how much will we have to pay?’ but ‘how much can we pull the financial rug from under Germany’s feet’ which will be the key factor in 2018. Supplementary question – does the Tory/DUP coalition have the Maggie Thatcher-style courage to go head-to-head with Germany?

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist.

John Coulter is a unionist political commentator and former Blanket columnist. Follow John Coulter on Twitter @JohnAHCoulterDr Coulter is also author of ‘ An Sais Glas: (The Green Sash): The Road to National Republicanism’, which is available on Amazon Kindle.

Published on January 01, 2018 03:00

December 31, 2017

Joe Armstrong

Anthony McIntyre shares his memories of a friend in neighbour from Belfast.

Not long before he died in March this year, Joe Armstrong wrote a piece for TPQ. He had been up and about in the early hours and was struck by the plight of the homeless. So he took to writing about it. Joe didn’t talk about people, he cared about them. I had hoped we would get more from him, but it was not to be.

Although he hailed from the Lower Ormeau Road, the same neck of the woods as myself, I didn’t actually meet him until I was released from prison and moved into Springhill. He lived a few houses away, at the bottom of the street. While his political sympathies lay with the IRSP, we never much discussed politics other than his dislike for the strong-arm tactics Sinn Fein employed in the area. When times were rough Joe was a reliable friend as were many others in the small cul de sac where we lived. He was great company to be in.

Over the years I would call on him regularly. We would smoke a joint, share a beer and chew the fat. We didn't go out on the booze much but on one occasion he accompanied a crowd of former blanket men out on a Christmas session. I later slagged him for not going the distance, he had taken enough and retired early. He later borrowed a book from me about the blanket protest written by Laurence McKeown and two other former prisoners. It is still borrowed! But most of the books Joe got from our shelves were novels for his partner Angie who read voraciously. Often, when I called on him I would end up talking to her about crime fiction.

Then there was the occasion when we got word that he had been arrested in Donegal for something minor but was being held until bailed out. The bail money was ridiculously low and we probably spent more in petrol making the journey to Ballybofey Garda Station and back. He was delighted to see me and we embraced as soon as I signed the bail papers. He and I took turns at the wheel on the return journey. We were joking that we would be arrested by the RUC for speeding along the Glenshane Pass, maybe even, in my case for being over the limit, but I can no longer recall if I brought tins for the return trip or not. Yeah, we were socially irresponsible and not politically correct, living life in the Orwell rather than the Orwellian sense of wanting to be good but not too good and not all the time.

When I moved down here I kept in touch with him after learning that he had taken ill. He was unfailingly supportive. His real passion was for his family and would email or text photos of them at an event or family gathering. He seemed to be on the mend, but then was snatched away by a heart attack. In his forties it was much too soon for the life of the “sexy bastard”, as he liked to jokingly refer to himself, to come to an abrupt end.

As we step across the line and move into 2018, we know that 2017 was that much better for having "Papa Joe" accompany us for part of the way.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Follow Anthony McIntyre on Twitter @AnthonyMcIntyre

Not long before he died in March this year, Joe Armstrong wrote a piece for TPQ. He had been up and about in the early hours and was struck by the plight of the homeless. So he took to writing about it. Joe didn’t talk about people, he cared about them. I had hoped we would get more from him, but it was not to be.

Although he hailed from the Lower Ormeau Road, the same neck of the woods as myself, I didn’t actually meet him until I was released from prison and moved into Springhill. He lived a few houses away, at the bottom of the street. While his political sympathies lay with the IRSP, we never much discussed politics other than his dislike for the strong-arm tactics Sinn Fein employed in the area. When times were rough Joe was a reliable friend as were many others in the small cul de sac where we lived. He was great company to be in.

Over the years I would call on him regularly. We would smoke a joint, share a beer and chew the fat. We didn't go out on the booze much but on one occasion he accompanied a crowd of former blanket men out on a Christmas session. I later slagged him for not going the distance, he had taken enough and retired early. He later borrowed a book from me about the blanket protest written by Laurence McKeown and two other former prisoners. It is still borrowed! But most of the books Joe got from our shelves were novels for his partner Angie who read voraciously. Often, when I called on him I would end up talking to her about crime fiction.

Then there was the occasion when we got word that he had been arrested in Donegal for something minor but was being held until bailed out. The bail money was ridiculously low and we probably spent more in petrol making the journey to Ballybofey Garda Station and back. He was delighted to see me and we embraced as soon as I signed the bail papers. He and I took turns at the wheel on the return journey. We were joking that we would be arrested by the RUC for speeding along the Glenshane Pass, maybe even, in my case for being over the limit, but I can no longer recall if I brought tins for the return trip or not. Yeah, we were socially irresponsible and not politically correct, living life in the Orwell rather than the Orwellian sense of wanting to be good but not too good and not all the time.

When I moved down here I kept in touch with him after learning that he had taken ill. He was unfailingly supportive. His real passion was for his family and would email or text photos of them at an event or family gathering. He seemed to be on the mend, but then was snatched away by a heart attack. In his forties it was much too soon for the life of the “sexy bastard”, as he liked to jokingly refer to himself, to come to an abrupt end.

As we step across the line and move into 2018, we know that 2017 was that much better for having "Papa Joe" accompany us for part of the way.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.Follow Anthony McIntyre on Twitter @AnthonyMcIntyre

Published on December 31, 2017 13:19

Keep Your God Off My Couch

Andrew McArthur blogging @ Atheist Republic advises:

Keep your god off my couch ... and don't forget to wipe your feet!

I was fortunate enough to pass through the early years of my childhood relatively unscathed by formal religious indoctrination. God probably came up once or twice, but as my parents were each members of different faiths, no particular importance seemed to be attached to him. Oh sure, we used to recite the Lord’s prayer in school, but that was just one more thing to get through before we could get out of there and get down to some serious fun. God, like Santa Clause and the Tooth Fairy were relegated to the ash heap of childhood fantasy once I began to realize that the real world bore scant resemblance to the realms of childhood mythology.

Despite this dearth of formal indoctrination, it was impossible to miss the dominant worldview that God created our world and everything in it for some inscrutable purpose. I still have vague memories of occasional “end of days” prophets roaming the neighborhood, harbingers of the wrath certain to descend upon us as punishment for our wicked ways. Being a child of the seventies, my imagination gave shape to these prophecies as nuclear holocaust; things were a little tense on the world stage at the time.

Now here it is decades later, and our eagerly anticipated doom has completely failed to materialize (much to the chagrin of the born again bunch who see such a cataclysm as a wonderful opportunity to unite with their god.) I can only assume that these “End Of Days” folks got their signals crossed somewhere along the way. God knows they weren’t the first.

Getting ready for the end

Segments of mankind have been awaiting the end almost since the beginning. This eagerness to put paid to the question of our earthly existence has motivated millions of ostensibly otherwise sane people to blindly follow anyone with sufficient oratory skills and a catchy slogan. Smugness reigns, as they are absolutely certain they will be among those saved when the time finally comes. Even today, many are looking forward to, and preparing for, the final battle between the forces of good and evil as foretold in the book of Revelations, certain they and their ilk will be on the winning team.

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have seen a dramatic rise in the visibility and popularity of the Evangelical Christian movement in North America. From the Canadian prairies to the American “Bible Belt,” Born Again Christians are attempting to foist their theocentric worldview on the rest of us, and achieving some notable successes. It is sobering to note that more than one past president of the United States; Commander In Chief of the largest nuclear arsenal on the planet, believed that God spoke to them personally and told them when to go to war. To be fair, they were not alone. The number of people cruelly murdered in any one of the many names of the One True God is impossible to calculate, but it is in the hundreds of millions to be sure.

Religions can no longer be tolerated

Religion is no longer some tolerable foible we can incorporate into our social and political fabric, it is nothing more than a tool used by desperate men and women (although predominantly men) to maintain their grip on power, and advance their personal agendas under the guise of piety. Religion is dangerous. We must outgrow our need for gods if we are ever to live up to our true potential as human being.

Paradoxically, it seems that if we are ever to re-enter the garden we need to understand that it never in fact existed and we are going to have to create it for ourselves. This is a call to arms. Our weapons are truth and communication. Demonstrable proof is our ammunition. At stake is nothing less than the future survival of our species. We have the ability to shape our own world and define our own experience. We need not tremble in fear at the terrors of the night. It’s time to put the demons back in the box.

Andrew McArthur is an Atheist Republic blogger and newsletter contributor.

Andrew McArthur is an Atheist Republic blogger and newsletter contributor.

Keep your god off my couch ... and don't forget to wipe your feet!

I was fortunate enough to pass through the early years of my childhood relatively unscathed by formal religious indoctrination. God probably came up once or twice, but as my parents were each members of different faiths, no particular importance seemed to be attached to him. Oh sure, we used to recite the Lord’s prayer in school, but that was just one more thing to get through before we could get out of there and get down to some serious fun. God, like Santa Clause and the Tooth Fairy were relegated to the ash heap of childhood fantasy once I began to realize that the real world bore scant resemblance to the realms of childhood mythology.

Despite this dearth of formal indoctrination, it was impossible to miss the dominant worldview that God created our world and everything in it for some inscrutable purpose. I still have vague memories of occasional “end of days” prophets roaming the neighborhood, harbingers of the wrath certain to descend upon us as punishment for our wicked ways. Being a child of the seventies, my imagination gave shape to these prophecies as nuclear holocaust; things were a little tense on the world stage at the time.

Now here it is decades later, and our eagerly anticipated doom has completely failed to materialize (much to the chagrin of the born again bunch who see such a cataclysm as a wonderful opportunity to unite with their god.) I can only assume that these “End Of Days” folks got their signals crossed somewhere along the way. God knows they weren’t the first.

Getting ready for the end

Segments of mankind have been awaiting the end almost since the beginning. This eagerness to put paid to the question of our earthly existence has motivated millions of ostensibly otherwise sane people to blindly follow anyone with sufficient oratory skills and a catchy slogan. Smugness reigns, as they are absolutely certain they will be among those saved when the time finally comes. Even today, many are looking forward to, and preparing for, the final battle between the forces of good and evil as foretold in the book of Revelations, certain they and their ilk will be on the winning team.

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have seen a dramatic rise in the visibility and popularity of the Evangelical Christian movement in North America. From the Canadian prairies to the American “Bible Belt,” Born Again Christians are attempting to foist their theocentric worldview on the rest of us, and achieving some notable successes. It is sobering to note that more than one past president of the United States; Commander In Chief of the largest nuclear arsenal on the planet, believed that God spoke to them personally and told them when to go to war. To be fair, they were not alone. The number of people cruelly murdered in any one of the many names of the One True God is impossible to calculate, but it is in the hundreds of millions to be sure.

Religions can no longer be tolerated

Religion is no longer some tolerable foible we can incorporate into our social and political fabric, it is nothing more than a tool used by desperate men and women (although predominantly men) to maintain their grip on power, and advance their personal agendas under the guise of piety. Religion is dangerous. We must outgrow our need for gods if we are ever to live up to our true potential as human being.

Paradoxically, it seems that if we are ever to re-enter the garden we need to understand that it never in fact existed and we are going to have to create it for ourselves. This is a call to arms. Our weapons are truth and communication. Demonstrable proof is our ammunition. At stake is nothing less than the future survival of our species. We have the ability to shape our own world and define our own experience. We need not tremble in fear at the terrors of the night. It’s time to put the demons back in the box.

Andrew McArthur is an Atheist Republic blogger and newsletter contributor.

Andrew McArthur is an Atheist Republic blogger and newsletter contributor.

Published on December 31, 2017 05:00

December 30, 2017

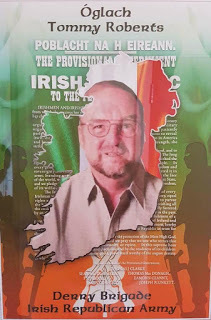

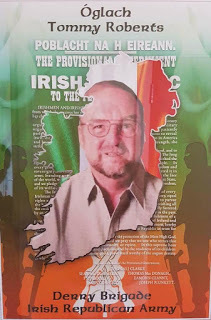

Tommy Roberts

Anthony McIntyre pays tribute to the first jail O/C he encountered during his imprisonment.

It was a Sunday afternoon in April 1974. I arrived on A Wing of Crumlin Road jail from the prison hospital just after lunch time lock up. One of the first people to greet me on the wing with a Derry accent was Tommy Roberts. He seemed old, but he was only in his early thirties. Although at 16, that made me half his age. Then, everybody twice my age looked old. He was the O/C of the republican remand prisoners in the jail.

One of the first things he asked me was whether I had led the prison riot that left the hospital wrecked. I told him honestly, that I had not. I was locked up at the time in a cell and not in the communal ward where the riot broke out. Apart from hearing the commotion I knew nothing about it.

At that young and impressionable age IRA leaders invariably seemed of a higher caste. We held them in a certain awe. I tended to revere Tommy. In the jail he was a quiet and reserved man. He would frequently excel at outdoor quoits which was favoured more by the older prisoners. Our generation preferred water fights.

Shortly after my arrival in the jail a poisoning scare broke out. British security agencies running agents in the prison hatched a plot to poison IRA leaders like Tommy and Brendan Hughes. We began refusing prison food, sustaining ourselves on what our families sent in via parcels. The hot water boilers in each of the canteens were under permanent guard by IRA volunteers. A tension and atmosphere of suspicion enveloped the prison. People on the wing one day would no longer be there the following. They were now in “the Annex” we were told. Rumours abounded, and the IRA intelligence people were not beyond the use of violence to extract information from those they suspected. Much of what they got was later proved to be nonsense. But the effect was to create a paranoia amongst the remand prisoners which extended into Cage 10 of Long Kesh. Brendan Hughes was later to describe some of it as akin to Japanese torture.

One of the saddest cases to emerge was that of Columba McVeigh. He arrived in the jail some time after Tommy Roberts was sentenced, only to admit during his debriefing that he too had been sent in to poison Brendan Hughes. It was probably the start of a dangerous odyssey for the young man which presumably led to his disappearance. His body has never been found. Others who had been on the wing and said to be involved in the plot were later shot dead by the IRA in Belfast.

So, Tommy Roberts led the prisoners at the start of a very volatile time, where he had to strive to protect those under his command, knowing at the same time that he was one of the primary targets. He dropped neither his guard nor his outward sense of calm. Shortly after it all blew up, he was sentenced to seven years and moved to Magilligan.

Four years later, when back in prison serving a life sentence in Cage 11, I read in the papers that Tommy had been arrested, stopped in a car ferrying him and others on a bombing operation. My first thought was that he was a bit old for it but admired him all the more for that.

The following year while lying in a filthy cell on the blanket protest, we learned that two new blanket men were on our wing. One of them was Tommy Roberts, the other Phil Nolan. The screws ribbed Tommy a bit about being born during the second world war, much too old to be hanging out with us. Tommy was one of the older blanket prisoners but he had the determination of youth. Such was his belief in the legitimacy of the IRA cause, He would never wear the prison uniform. I was delighted to see him although I would have preferred it to be in a different location with both of us more suitably attired.

Tommy was a realist and did not share the hopes of many of the blanketmen that the protest would be quickly resolved. He settled down for the long haul that it proved to be, and was there to the end. So when the following words were delivered during his funeral eulogy, I immediately recognised them as hyperbole-free.

When the protest ended I would meet up with him on different wings. By then he was Tommy Bap. How he got that handle I have no idea, but he was regarded and revered as one of the republican veterans.

When inquiring about him from a former Derry prisoner last year, I learned that he was doing poorly. The information was not wrong because he succumbed to the illness in June. His funeral was a republican affair. When Sinn Fein members arrived at the home with a wreath they were told where to go by his widow, Molly, herself a former republican prisoner. Tommy, apparently, loathed the Sinn Fein jettisoning of republicanism, seeing in it little other than an opportunistic grab for careers and booty. Tommy felt too much for the volunteers who had lost their lives to see their sacrifices traded in for political bling and no republican substance.

Forty five years after he had stood in a field on active service alongside two other unarmed IRA volunteer, when the British Army fired on them, leaving James “Junior” McDaid dead, Tommy’s own life ended. He had lost none of the republicanism that he carried through that field at Ballyarnett, or in the dank cells of the H Blocks blanket protest.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Anthony McIntyre blogs @ The Pensive Quill.

Follow Anthony McIntyre on Twitter @AnthonyMcIntyre

It was a Sunday afternoon in April 1974. I arrived on A Wing of Crumlin Road jail from the prison hospital just after lunch time lock up. One of the first people to greet me on the wing with a Derry accent was Tommy Roberts. He seemed old, but he was only in his early thirties. Although at 16, that made me half his age. Then, everybody twice my age looked old. He was the O/C of the republican remand prisoners in the jail.

One of the first things he asked me was whether I had led the prison riot that left the hospital wrecked. I told him honestly, that I had not. I was locked up at the time in a cell and not in the communal ward where the riot broke out. Apart from hearing the commotion I knew nothing about it.

At that young and impressionable age IRA leaders invariably seemed of a higher caste. We held them in a certain awe. I tended to revere Tommy. In the jail he was a quiet and reserved man. He would frequently excel at outdoor quoits which was favoured more by the older prisoners. Our generation preferred water fights.

Shortly after my arrival in the jail a poisoning scare broke out. British security agencies running agents in the prison hatched a plot to poison IRA leaders like Tommy and Brendan Hughes. We began refusing prison food, sustaining ourselves on what our families sent in via parcels. The hot water boilers in each of the canteens were under permanent guard by IRA volunteers. A tension and atmosphere of suspicion enveloped the prison. People on the wing one day would no longer be there the following. They were now in “the Annex” we were told. Rumours abounded, and the IRA intelligence people were not beyond the use of violence to extract information from those they suspected. Much of what they got was later proved to be nonsense. But the effect was to create a paranoia amongst the remand prisoners which extended into Cage 10 of Long Kesh. Brendan Hughes was later to describe some of it as akin to Japanese torture.

One of the saddest cases to emerge was that of Columba McVeigh. He arrived in the jail some time after Tommy Roberts was sentenced, only to admit during his debriefing that he too had been sent in to poison Brendan Hughes. It was probably the start of a dangerous odyssey for the young man which presumably led to his disappearance. His body has never been found. Others who had been on the wing and said to be involved in the plot were later shot dead by the IRA in Belfast.

So, Tommy Roberts led the prisoners at the start of a very volatile time, where he had to strive to protect those under his command, knowing at the same time that he was one of the primary targets. He dropped neither his guard nor his outward sense of calm. Shortly after it all blew up, he was sentenced to seven years and moved to Magilligan.