Tom Stafford's Blog, page 35

April 27, 2014

Spike activity 25-04-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Induced hallucination turns doctors into pizza chefs. New Scientist on a recent brain stimulation study that sadly didn’t actually get doctors to make pizza.

The Telelgraph has an interesting piece on human vision and its impossibilities.

There’s an excellent piece in The Guardian asking whether misused developmental neuroscience is defining early years and child protection policy.

New Republic has a fascinating piece on how different personality traits are in expressed when multi-linguals speak in different languages.

Drama in the teenage brain! The excellent science journal for kids – Frontiers for Young Minds – covers how the brain develops during adolescence.

TV Needs to Stop Treating Mental Illness as a Superpower says New Republic. It’s a step-up from treating it as a horror but still a poor cliché.

Nautilus has a fascinating piece on the quest to build the perfect painkiller – which doesn’t get you addicted.

Could the menstrual cycle have shaped the evolution of music? asks Science News.

Emotion Review has a meta-analysis of menstrual cycle effects on women’s mate preferences and finds little except publication bias.

The Face Recognition Algorithm That Finally Outperforms Humans. The Physics arXiv Blog covers the latest advance in face recognition AI.

April 25, 2014

Research Digest #3: Getting to grips with implicit bias

My third and final post at the BPS Research Digest is now up: Getting to grips with implicit bias. Here’s the intro:

Implicit attitudes are one of the hottest topics in social psychology. Now a massive new study directly compares methods for changing them. The results are both good and bad for those who believe that some part of prejudice is our automatic, uncontrollable, reactions to different social groups.

All three studies I covered (#1, #2, #3) use large behavioural datasets, something I’m particularly keen on in my own work.

Link: Getting to grips with implicit bias

April 24, 2014

Heartbreak among the roses

British Pathé, the vintage news organisation, have released all of their archive online including some fascinating newsreels on psychiatric institutions of times past.

A particularly interesting film is Inside Rampton! a 1957 newsreel which focuses on Rampton Secure Hospital – which was, and still is, one of England’s three highest security psychiatric hospitals.

The others are Ashworth and the more widely known Broadmoor Hospital – all three of which are designed to treat mental illness in people who pose a serious risk to the public.

On of the points of the film is to report on the hospital following accusations, common at the time, that people were admitted to the institution despite having ‘nothing wrong with them’ and that patients were subject to harsh treatment.

You can read about the controversy in this 1957 Spectator article that talks about the classic and still relevant tension in forensic mental health services between treatment and legal sanction.

Both the film and the article mention the case of Marie Mayo, who was sent to the hospital due to an ‘administrative error’ causing a significant scandal. One of the other Pathé films is a brief report on her release and return home.

There was widespread public concern at the time that psychiatric institutions were randomly locking people up and that residents were subject to abuse.

The Inside Rampton! film is the first wave of serious concern that subsequently led to Enoch Powell’s ‘water tower’ speech and the political moves to bring down the asylum system, as well as the anti-psychiatry movement and its push for a radical approach to mental distress.

Link to Inside Rampton! on YouTube.

Link to Spectator article ‘Heartbreak among the roses’.

Research Digest post #2

My time in the BPS Research Digest hotseat continues. Today’s post is about a lovely study by Stuart Ritchie and colleagues which uses a unique dataset to look at the effect of alcohol on cognitive function across the lifespan. Here’s the intro:

The cognitive cost or benefit of booze depends on your genes, suggests a new study which uses a unique longitudinal data set.

Inside the laboratory psychologists use a control group to isolate the effects of specific variables. But many important real world problems can’t be captured in the lab. Ageing is a good example: if we want to know what predicts a healthy old age, running experiments is difficult, even if only for the reason that they take a lifetime to get the results. Questions about potentially harmful substances are another good example: if we suspect something may be harmful we can hardly give it to half of a group of volunteer participants. The question of the long-term effects of alcohol consumption on cognitive ability combines both of these difficulties.

You can read the rest here: Alcohol could have cognitive benefits – depending on your genes.

See also, Tuesday’s post: A self-fulfilling fallacy?

April 23, 2014

Research Digest posts, #1: A self-fulfilling fallacy?

This week I will be blogging over at the BPS Research Digest. The Digest was written for over ten years by psychology-writer extraordinaire Christian Jarrett, and I’m one of a series of guest editors during the transition period to a new permanent editor.

My first piece is now up, and here is the opening:

Lady Luck is fickle, but many of us believe we can read her mood. A new study of one year’s worth of bets made via an online betting site shows that gamblers’ attempts to predict when their luck will turn has some unexpected consequences.

Read the rest over at the digest, I’ll post about the other stories I’ve written as they go up.

April 22, 2014

Why all babies love peekaboo

Peekaboo is a game played over the world, crossing language and cultural barriers. Why is it so universal? Perhaps because it’s such a powerful learning tool.

One of us hides our eyes and then slowly reveals them. This causes peals of laughter from a baby, which causes us to laugh in turn. Then we do it again. And again.

Peekaboo never gets old. Not only does my own infant daughter seem happy to do it for hours, but when I was young I played it with my mum (“you chuckled a lot!” she confirms by text message) and so on back through the generations. We are all born with unique personalities, in unique situations and with unique genes. So why is it that babies across the world are constantly rediscovering peekaboo for themselves?

Babies don’t read books, and they don’t know that many people, so the surprising durability and cultural universality of peekaboo is perhaps a clue that it taps into something fundamental in their minds. No mere habit or fashion, the game can help show us the foundations on which adult human thought is built.

An early theory of why babies enjoy peekaboo is that they are surprised when things come back after being out of sight. This may not sound like a good basis for laughs to you or I, with our adult brains, but to appreciate the joke you have to realise that for a baby, nothing is given. They are born into a buzzing confusion, and gradually have to learn to make sense of what is happening around them. You know that when you hear my voice, I’m usually not far behind, or that when a ball rolls behind a sofa it still exists, but think for a moment how you came by this certainty.

The Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget called this principle ‘object permanence’ and suggested that babies spent the first two years of their lives working it out. And of course those two years are prime peekaboo time. Looked at this way, the game isn’t just a joke, but helps babies test and re-test a fundamental principle of existence: that things stick around even when you can’t see them.

Maybe evolution fixed it so that babies enjoy peekaboo for its own sake, since it proved useful in cognitive development, but I doubt it. Something deeper than mere education is going on.

Surprise element

Peekaboo uses the fundamental structure of all good jokes – surprise, balanced with expectation. Researchers Gerrod Parrott and Henry Gleitman showed this in tests involving a group of six-, seven- and eight-month-olds which sound like more fun than a psychology experiment should be. Most of the time the peekaboo game proceeded normally, however on occasion the adult hid and reappeared as a different adult, or hid and reappeared in a different location. Videos of the infants were rated by independent observers for how much the babies smiled and laughed.

On these “trick trials” the babies smiled and laughed less, even though the outcome was more surprising. What’s more, the difference between their enjoyment of normal peekaboo and trick-peekaboo increased with age (with the eight-month-olds enjoying the trick trials least). The researchers’ interpretation for this is that the game relies on being able to predict the outcome. As the babies get older their prediction gets stronger, so the discrepancy with what actually happens gets larger – they find it less and less funny.

The final secret to the enduring popularity of peekaboo is that it isn’t actually a single game. As the baby gets older their carer lets the game adapt to the babies’ new abilities, allowing both adult and infant to enjoy a similar game but done in different ways. The earliest version of peekaboo is simple looming, where the carer announces they are coming with their voice before bringing their face into close focus for the baby. As the baby gets older they can enjoy the adult hiding and reappearing, but after a year or so they can graduate to take control by hiding and reappearing themselves.

In this way peekaboo can keep giving, allowing a perfect balance of what a developing baby knows about the world, what they are able to control and what they are still surprised by. Thankfully we adults enjoy their laughter so much that the repetition does nothing to stop us enjoying endless rounds of the game ourselves.

This is my BBC Future column from last week. The original is here

April 21, 2014

A history of the mind in 25 parts

BBC Radio 4 has just kicked off a 25-part radio series called ‘In Search of Ourselves: A History of Psychology and the Mind’.

BBC Radio 4 has just kicked off a 25-part radio series called ‘In Search of Ourselves: A History of Psychology and the Mind’.

Because the BBC are not very good at the internet, there are no podcasts – streaming audio only, and each episode disappears after seven days. Good to see the BBC are still on the cutting edge of 20th Century media.

The series looks fantastic however and it aims to cover psychology, psychiatry, neuroscience and the diverse history of dealing with mental distress.

The first episode is already online so worth tuning in while you can.

Link to In Search of Ourselves: A History of Psychology and the Mind.

Detecting inner consciousness

Mosaic has an excellent in-depth article on researchers who are trying to detect signs of consciousness in patients who have fallen into coma-like states.

Mosaic has an excellent in-depth article on researchers who are trying to detect signs of consciousness in patients who have fallen into coma-like states.

The piece meshes the work of neuroscientists Adrian Owen, Nicholas Schiff and Steven Laureys who are independently looking at how to detect signs of consciousness in unresponsive brain-injured patients.

It’s an excellent piece and communicates the key difference between various states of poor response after brain injury that are crucial for making sense of the ‘consciousness in coma’ headlines.

One of the key concepts is the minimally conscious state which is where patients show signs of fleeting and impaired consciousness but which is nonetheless verifiably present.

However, MCS is still a very impaired state to be in and this is sometimes missed by news reports.

For example, lots of coverage of a recent Lancet study suggested that ‘one third of patients in persistent vegetative state (a state with no reliable signs of consciousness) may be conscious’ as if this meant they were fully conscious but trapped in their bodies, when actually they just reached criteria for minimally conscious state.

My only point of contention with the Mosaic article is that it’s a little too enthusiastic about sleeping pill zolpidem, which has been reported to lead to a ‘miraculous’ recovery in some case report but where results from early systematic studies still look bleak.

Nevertheless, an excellent piece that’s probably one of the best accounts of this important and innovative area of research you’re likely to read for a long-time.

Link to Mosaic article ‘The Mind Readers’.

April 19, 2014

Spike activity 18-04-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Wired has a fascinating interview with psychopath researcher Kent Kiehl. He of the mobile brain scanner.

Scanning brain energy could help predict who will wake from vegetative state. Interesting piece on preliminary research covered by The Conversation

Contrary to news stories, a recent study did not tell us that smoking weed damages your brain, reports The Daily Beast.

Gay genes? Yeah, but no, well kind of… but, so what? Excellent piece from Wiring the Brain. You guys all read Wiring the Brain right?

The Association for Psychological Science has an archive of interviews with legends of psychological science. Harlow’s wire monkey, the Bobo doll, Mischel’s uneaten marshmallow…

In Search of Ourselves: A History of Psychology and the Mind. An extensive 25-part radio series on the history of psychology kicks off on Monday 25th April on BBC Radio 4.

The United Nations release a report that has everything you ever wanted to know about your chance of being murdered. Pro-tip: don’t be male.

The evolutionary psychology of facial furniture. Scicurious on the behavioural science of beards.

Scientific American Mind reports on highlights from the recent Cognitive Neuroscience Society Annual Meeting.

Irrationality ninja Dan Ariely has a kickstarter to make a documentary on dishonesty. 20 days left, a few more backers and it could make it. Looks fascinating.

Bloomberg on the booming business in behavioral finance. Although why not apply it to bankers rather than consumers to stop them fucking the economy? You can put the economics Nobel in the post.

A fascinating piece on the social and biopolitical role of bleach in a Nicaraguan community from the ever excellent Somatosphere.

April 18, 2014

Indie reports on surprising structure of artists’ brains

Artists brains are ‘structurally different’ according to The Independent, who report on a small, thought-provoking but as yet quite preliminary study.

Artists brains are ‘structurally different’ according to The Independent, who report on a small, thought-provoking but as yet quite preliminary study.

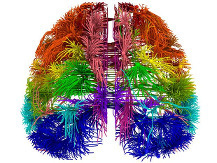

The image used to illustrate the article (the one on the right) is described as showing “more grey and white matter in artists’ brains connected to visual imagination and fine motor control”.

This could be a bit alarming, especially if you are an artist, because that’s actually a map of a mouse brain.

Whether artists have ‘different brains’ or not, in any meaningful sense, is perhaps slightly beside the point, but you can be rest assured that they’re not so different that they will give you a sudden desire to scamper around looking for cheese.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers