Tom Stafford's Blog, page 33

June 21, 2014

Spike activity 20-06-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

OK Go’s new music video is like standing naked under a waterfall of optical illusions while wearing hipster spectacles.

The mighty Neurocritic looks at advances in physical brain tweaking and the possible rebirth of paradise engineering.

The Dana Foundation has an excellent piece on how to make sense of those ‘gene for’ behavioural genetics stories in the media.

Slow news day: The New York Times reports my killer robot opinions. Sadly the key quote (“To the bunkers if you want any chance of saving yourselves from the coming robotocalypse. RUN, RUN FOR YOUR LIVES!”) was omitted.

PsyPost reports on a new study finding that the ‘trophy wife’ stereotype is largely a myth, because not even good looks can break the class barrier.

Watching porn won’t shrink your brain. Just makes you a bit sore. Brain Watch comments on a widely misreported recent study.

The Atlantic has a great piece on five neurology patients who the way we think about the brain.

There’s an excellent article about maternal mental health in The New York Times.

Simon says Psychosis! is an excellent new mini-documentary on the first experience of psychosis and early intervention services.

The ever-interesting neuroscientist Molly Crockett is featured in this Wellcome Trust focus on scientists’ working days.

June 15, 2014

A peek inside The Skeleton Cupboard

You’ll get more out of The Skeleton Cupboard, Tanyan Byron’s account of her training as a clinical psychologist, if you read the epilogue first.

You’ll get more out of The Skeleton Cupboard, Tanyan Byron’s account of her training as a clinical psychologist, if you read the epilogue first.

It tells you that the patients described in the book are fictional, to preserve confidentiality, but indicates that the stories were representative of real situations.

This is a common device in clinical memoires, from Irvin Yalom’s existential tales of psychotherapy to Philippa Perry’s couch fiction, but I’m never quite sure what to make of these clinical quasi-biographies.

They are usually realistic, insightful and wonderful to read, Byron’s book is no exception, but the smudged line between truth and necessary fiction is sometimes hard to navigate.

In Byron’s case, her book is perhaps the most deliberately autobiographical in the genre, where she intends to reflect the role of the psychologist’s own psychology in working with distressed, impaired, and sometimes difficult individuals.

This is part of what clinical psychologists aim to do – understand how your own reactions are colouring your approach to the patient – but when the patients are literary collages of real people, it is perhaps the process rather than the content of those reflections that are the most informative.

From this perspective, The Skeleton Cupboard is best understood as an illustrated history of ‘how my thinking evolved as a clinician’ rather than a journal of patients past, although we assume the non-clinical parts are factual: the hard-boiled supervisor, the misjudged snogging of a psychiatrist, the friends through good times and bad.

Byron is Britain’s best ambassador for clinical psychology and a very good writer to boot and I’m sure The Skeleton Cupboard will prompt many to take up the profession or inspire them during their training. It’s also a good account of how thinking and practice evolves through first contact with patients.

It has some artistic license, maybe even melodrama in places, but it has some points of emotional truth that are hard to deny.

Link to more details of The Skeleton Cupboard.

June 9, 2014

Nostalgia: Why it is good for you

The past is not just a foreign country, but also one we are all exiled from. Like all exiles, we sometimes long to return. That longing is called nostalgia.

Whether it is triggered by a photograph, a first kiss or a treasured possession, nostalgia evokes a particular sense of time or place. We all know the feeling: a sweet sadness for what is gone, in colours that are invariably sepia-toned, rose-tinted, or stained with evening sunlight.

The term “nostalgia” was coined by Swiss physicians in the late 1600s to signify a certain kind of homesickness among soldiers. Nowadays we know it encompasses more than just homesickness (or indeed Swiss soldiers), and if we take nostalgia too far it becomes mawkish or indulgent.

But, perhaps, it has some function beyond mere sentimentality. A series of investigations by psychologist Constantine Sedikides suggest nostalgia may act as a resource that we can draw on to connect to other people and events, so that we can move forward with less fear and greater purpose.

Sedikides was inspired by something called Terror Management Theory (TMT), which is approximately 8,000 times sexier than most theories in psychology, and posits that a primary psychological need for humans is to deal with the inevitability of our own deaths. The roots of this theory are in the psychoanalytic tradition of Sigmund Freud, making the theory a bit different from many modern psychological theories, which draw on more mundane inspirations, such as considering the mind as a computer.

Experiments published in 2008 used a standard way to test Terror Management Theory: asking participants to think about their own deaths, answering questions such as: “Briefly describe the emotions that the thought of your own death arouses in you.” (A control group was asked to think about dental pain, something unpleasant, but not existentially threatening.)

TMT suggests that one response to thinking about death is to cling more strongly to the view that life has some wider meaning, so after their intervention they asked participants to indicate their agreement with statements such as: “Life has no meaning or purpose”, or “All strivings in life are futile and absurd”. From the answers they positioned participants on a scale of how strongly they felt life had meaning.

The responses were influenced by how prone people were to nostalgia. The researchers found that reminding participants of their own deaths was likely to increase feelings of meaninglessness, but only in those who reported that they were less likely to indulge in nostalgia. Participants who rated themselves as more likely than average to have nostalgic thoughts weren’t affected by negative thoughts about their mortality (they rated life as highly meaningful, just like the control group).

Follow-up experiments suggest that people prone to nostalgia were less likely to have lingering thoughts about death, as well as less likely to be vulnerable to feelings of loneliness. Nostalgia, according to this view, is very different from a weakness or indulgence. The researchers call it a “meaning providing resource”, a vital part of mental health. Nostalgia acts a store of positive emotions in memory, something we can access consciously, and perhaps also draw on continuously during our daily lives to bolster our feelings. It’s these strong feelings for our past that helps us cope better with our future.

Thanks to Jules Hall for suggesting the topic of nostalgia. If you have an everyday psychological phenomenon you’d like to see written about in these columns please get in touch @tomstafford or ideas@idiolect.org.uk

This was my BBC Future column from last week. The original is here.

June 8, 2014

Spike activity 06-06-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Psychedelic chemist, godfather of Ecstasy, and lover of phenethylamines, Alexander Shulgin, has left the building. PhysOrg has an obituary.

New Republic looks back at 50 years of the landmark account of psychosis ‘I Never Promised You a Rose Garden’.

The US Secret Service wants a sarcasm detection tool for Twitter reports The Telegraph. Their irony detection tool is apparently still switched off.

Aeon Magazine has a piece on how artificial intelligence is being used to develop the first generation of sex robots. Voight-Kampff plugin for Tinder coming soon.

British folk: Now that BBC Future is available to people in the country it is based in, do check out its large cache of excellent psychology and neuroscience articles.

Mosaic has an extensive article on the US Military’s interest in boosting the brain by passing small electrical currents through it.

Go check out this excellent piece on ‘mirror neurons’ and what they’re likely to be actually doing from Nautilus magazine.

Advances in the History of Psychology blog has an interesting piece on how Little Albert may not have been correctly identified after all.

How to Criticize with Kindness: Philosopher of Mind Daniel Dennett brings some wisdom and describes the four steps to arguing intelligently over at Brain Pickings.

The Economist has a great interview with risk psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer.

A festival of anxious art

If you’re in London during June, the Anxiety Arts Festival is surprisingly diverse and interesting series of events that looks at anxiety through film, theatre and visual arts.

If you’re in London during June, the Anxiety Arts Festival is surprisingly diverse and interesting series of events that looks at anxiety through film, theatre and visual arts.

The festival is being curated by the Mental Health Foundation who have put together a genuinely exciting programme that avoids the curse of constant niceness and goes into some quite challenging areas.

Highlights include the darkly comic play Non-stop Exotic Anxiety, Ian Curtis and Joy Division biopic Control, South London Gallery exhibition The Military Industrial Complex on consensual reality, the irrepressible CoolTan Arts event Mad Hatters Tea Party, and Hearing Things – a theatre production of improvised scenes with mental health service users, professionals, and professional actors.

There’s masses more events and its one not to miss.

Link to Anxiety Festival.

June 6, 2014

Happy Birthday Tetris!

Released on 6th of June 1984, Tetris is 30 years old today. Here’s a video where I try and explain something of the psychology of Tetris:

All credit for the graphics to Andrew Twist. What I say in the video is based on an article I wrote a while back for BBC Future.

As well as hijacking the minds and twitchy fingers of puzzle-gamers for 30 years, Tetris has also been involved in some important psychological research.

My favourite is Kirsh and Maglio’s work on “epistemic action“, which showed how Tetris players prefer to rotate the blocks in the game world rather than mentally. This using the world in synchrony with your mental representations is part of what makes it so immersive, I argue.

Other research has looked at whether Tetris’s hook on our visual imagery can be used to help people with PTSD flashbacks.

And don’t forget that Tetris was the control condition is Green and Bavelier’s now famous studies of how action video games can train visual attention

In my own research I’ve used simple games to explore skill learning. John Lindstedt and Wayne Gray at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have been pursuing a parallel line looking at expertise in Tetris players.

I’m sure there are more examples, if you know of any researching using Tetris let me know. Happy Birthday Tetris!

June 1, 2014

Spike activity 30-05-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

If you’ve not been keeping up with the internet, there’s been a replication crisis hoedown and everyone’s had a go on the violin.

Political Science Replication had a good summary. Schnall’s reply, the rise of ‘negative psychology’ and a pointed response.

Military Plans To Test Brain Implants To Fight Mental Disorders reports NPR. If only there was some way to avoid traumatising people…

The BPS Research Digest has been hosting some amazing guest mind and brain writers and here’s an index to all their articles.

The Myth of Einstein’s Brain. Neuroskeptic has an excellent piece about how studies of his kidnapped brain don’t actually tell us much.

The Best Illusion of the Year contest has just announced it’s 2014 winners.

Spacetimemind is a new podcast with some good philosophy of mind material.

Neuroscientists win 2014 Kavli Prize in neuroscience: Brenda Milner, John O’Keefe, and Marcus Raichle

The Blind Woman Who Sees Rain, But Not Her Daughter’s Smile. Another fascinating piece from NPR.

Brain Watch asks ‘what happens if you apply electricity to the brain of a corpse?’ Don’t try this at home.

Philosopher fight in the New York Review of Books: Patricia Churchland and Colin McGinn on brains and minds and retorts like only philosophers can manage.

May 26, 2014

The best way to win an argument

How do you change someone’s mind if you think you are right and they are wrong? Psychology reveals the last thing to do is the tactic we usually resort to.

You are, I’m afraid to say, mistaken. The position you are taking makes no logical sense. Just listen up and I’ll be more than happy to elaborate on the many, many reasons why I’m right and you are wrong. Are you feeling ready to be convinced?

Whether the subject is climate change, the Middle East or forthcoming holiday plans, this is the approach many of us adopt when we try to convince others to change their minds. It’s also an approach that, more often than not, leads to the person on the receiving end hardening their existing position. Fortunately research suggests there is a better way – one that involves more listening, and less trying to bludgeon your opponent into submission.

A little over a decade ago Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil from Yale University suggested that in many instances people believe they understand how something works when in fact their understanding is superficial at best. They called this phenomenon “the illusion of explanatory depth“. They began by asking their study participants to rate how well they understood how things like flushing toilets, car speedometers and sewing machines worked, before asking them to explain what they understood and then answer questions on it. The effect they revealed was that, on average, people in the experiment rated their understanding as much worse after it had been put to the test.

What happens, argued the researchers, is that we mistake our familiarity with these things for the belief that we have a detailed understanding of how they work. Usually, nobody tests us and if we have any questions about them we can just take a look. Psychologists call this idea that humans have a tendency to take mental short cuts when making decisions or assessments the “cognitive miser” theory.

Why would we bother expending the effort to really understand things when we can get by without doing so? The interesting thing is that we manage to hide from ourselves exactly how shallow our understanding is.

It’s a phenomenon that will be familiar to anyone who has ever had to teach something. Usually, it only takes the first moments when you start to rehearse what you’ll say to explain a topic, or worse, the first student question, for you to realise that you don’t truly understand it. All over the world, teachers say to each other “I didn’t really understand this until I had to teach it”. Or as researcher and inventor Mark Changizi quipped: “I find that no matter how badly I teach I still learn something”.

Explain yourself

Research published last year on this illusion of understanding shows how the effect might be used to convince others they are wrong. The research team, led by Philip Fernbach, of the University of Colorado, reasoned that the phenomenon might hold as much for political understanding as for things like how toilets work. Perhaps, they figured, people who have strong political opinions would be more open to other viewpoints, if asked to explain exactly how they thought the policy they were advocating would bring about the effects they claimed it would.

Recruiting a sample of Americans via the internet, they polled participants on a set of contentious US policy issues, such as imposing sanctions on Iran, healthcare and approaches to carbon emissions. One group was asked to give their opinion and then provide reasons for why they held that view. This group got the opportunity to put their side of the issue, in the same way anyone in an argument or debate has a chance to argue their case.

Those in the second group did something subtly different. Rather that provide reasons, they were asked to explain how the policy they were advocating would work. They were asked to trace, step by step, from start to finish, the causal path from the policy to the effects it was supposed to have.

The results were clear. People who provided reasons remained as convinced of their positions as they had been before the experiment. Those who were asked to provide explanations softened their views, and reported a correspondingly larger drop in how they rated their understanding of the issues. People who had previously been strongly for or against carbon emissions trading, for example, tended to became more moderate – ranking themselves as less certain in their support or opposition to the policy.

So this is something worth bearing in mind next time you’re trying to convince a friend that we should build more nuclear power stations, that the collapse of capitalism is inevitable, or that dinosaurs co-existed with humans 10,000 years ago. Just remember, however, there’s a chance you might need to be able to explain precisely why you think you are correct. Otherwise you might end up being the one who changes their mind.

This is my BBC Future column from last week. The original is here.

May 25, 2014

The day video games ate my school child

The BBC is reporting that a UK teachers union “is calling for urgent action over the impact of modern technology on children’s ability to learn” and that “some pupils were unable to concentrate or socialise properly” due to what they perceive as ‘over-use’ of digital technology.

The BBC is reporting that a UK teachers union “is calling for urgent action over the impact of modern technology on children’s ability to learn” and that “some pupils were unable to concentrate or socialise properly” due to what they perceive as ‘over-use’ of digital technology.

Due to evidence reviewed by neuroscientist in a recent paper (pdf) we know that we’ve really got no reason to worry about technology having an adverse effects on kids’ brains.

It may not be that the teachers’ union is completely mistaken, however. They may be on to something but maybe just not what they think they’re onto.

To make sense of the confusion, you need to check out an elegant study completed by psychologists Robert Weis and Brittany Cerankosky who decided to test the psychological effects of giving young boys video game consoles.

They asked for families to take part who did not have a video-game system already in their home, had a parent interested in purchasing a system for their use, and where the kid had no history of developmental, behavioural, medical, or learning problems.

They ran a randomised controlled trial or RCT where 6 to 9-year-old boys were first given neuropsychological tests to measure their cognitive abilities (memory, concentration and problem-solving) and then randomly assigned to get a video games console.

The families in the control group were promised a console at the end of the study, by the way, so they didn’t think ‘oh sod it’ and go and buy one anyway.

So, we have half the kids with spanking brand new console, and, as part of the trial, the amount of time kids spent gaming and doing their school work was measured throughout, as was reporting of any behavioural problems. At the end of the study their academic progress was measured and their cognitive abilities were tested again.

The results were clear: kids who got video game consoles were worse off academically compared to their non-console-owning peers – their progress in reading and writing had suffered.

But this wasn’t due to an impact on their concentration, memory, problem-solving or behaviour – their neuropsychological and social performance was completely unaffected.

By looking at how much time the kids spent on the consoles, they found that reduced academic performance was due to the fact that kids in the console-owning families started spending less time doing their homework.

In other words, if your kids play a lot of computer games instead of doing homework they may well appear worse off, and from the teachers’ point-of-view, might seem a little slowed-down compared to their peers, but this is not due to cognitive changes.

Interestingly, teachers may not be in the best position to see this distinction very well because they tend, like the rest of us, to measure ability by performance in the tasks they set and not in comparison to neuropsychological test performance.

The solution is not to panic about technology as this same conclusion probably applies to anything that displaces homework (too many piano lessons will have the same effect) but good parental management of out-of-school time is clearly important.

Link to locked study on the effects of video games.

May 24, 2014

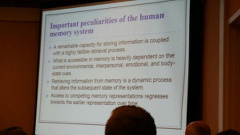

Important peculiarities of memory

A slide from what looks like a fascinating talk by memory researcher Robert Bjork is doing the rounds on Twitter.

A slide from what looks like a fascinating talk by memory researcher Robert Bjork is doing the rounds on Twitter.

The talk has just happened at the Association for Psychological Science 2014 conference and it describes some ‘Important peculiarities of memory’.

You can click the link above if you want to see if the image, but as it’s a little fuzzy, I’ve reproduced Robert Bjork’s text below:

Important peculiarities of the human memory system

A remarkable capacity for storing information is coupled with a highly fallible retrieval process.

What is accessible in memory is highly dependent on the current environmental, interpersonal, emotional and body-state cues.

Retrieving information from memory is a dynamic process that alters the subsequent state of the system.

Access to competing memory representations regresses towards the earlier representation over time

A lovely summary of memory’s quirks.

Link to Robert Bjork’s staff page.

Link to APS 2014 page with videos of the keynote talks.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers