Tom Stafford's Blog, page 122

October 2, 2010

A nasty case of misery

BBC Radio 4 has a short but excellent programme on the increasing medicalisation of human sadness which notes that even everyday talk about difficult but necessary life events is being increasingly couched in medical terms.

BBC Radio 4 has a short but excellent programme on the increasing medicalisation of human sadness which notes that even everyday talk about difficult but necessary life events is being increasingly couched in medical terms.

The writer and presenter of the piece, journalist Mary Kenny, notes, for example, how the concept of trauma is being increasingly applied to mourning, previously considered a painful but normal response to tragic circumstances. She also tackles how this tendency is being reflecting in the ongoing widening of the criteria for mental illness.

Kenny's piece neither relies on tired simplifications of 'evil drug companies' nor falls back on simple explanations for mental illness and makes for a insightful short analysis of how our understanding of human distress is changing.

Unfortunately, you can only listen to a streamed version of the piece and it will disappear in four days, so catch it while you can.

Link to 'Medicalising Melancholy' on BBC Radio 4.

Link to article on BBC News website based on the programme.

The taste of the past

The latest edition of The Psychologist has a fascinating article on 'sensory history' – the practice of investigating how people from the past differently interpreted and understood sensory experiences.

The latest edition of The Psychologist has a fascinating article on 'sensory history' – the practice of investigating how people from the past differently interpreted and understood sensory experiences.

I was first alerted to the idea by a book review we covered back in 2009 which noted that the superstition of the 'evil eye' – where you can curse someone by looking at them – makes more sense when you realise people believed that the eyes actively emitted rays rather than passively receiving them.

This new article is by sensory historian Mark Smith, author of the book Sensing the Past, who examines how the meaning of the senses has changed over time.

This part particularly caught my eye (pun intended) as it describes how the print revolution made the sense of sight seem more 'truthful' and 'objective':

In part, at least, historians of the sensate attend to the nonvisual senses principally because we have, for so long, assumed the supremacy of the eye in the human sensorium. Historical interest in smell, sound, touch and taste has been animated often because of the assumed ascendancy of vision that emerged following the print revolution and the developments of the Enlightenment, many of which supposedly elevated the eye as the arbiter of truth, the producer of perspective and balance (courtesy of the invention and subsequent dissemination of visual technologies such as the telescope, microscope and camera) and, in the process, diluted the value placed on the nonvisual, often proximate senses of hearing, olfaction, tasting, and touching.

It seems – or, at least, some sensory historians now theorise – that this supposed revolution in the senses was so thoroughgoing that moderns –at least those of the Western 18th-, 19th- and 20th-century variety – increasingly dismissed the other senses as reliable indicators of reason and truth and, instead, came to associate them with emotionalism or, more often than not, hardly worthy of sustained scholarly investigation.

Link to 'The explosion of sensory history'.

Full disclosure: I'm an unpaid associate editor and occasional columnist for The Psychologist who has trouble sensing breakfast, let alone history.

October 1, 2010

Inattention to details

Neuroskeptic has excellent coverage of the recent headline-making study on the genetics of ADHD that was overly-hyped as the 'first direct genetic link' to the disorder and overly-slammed as a drug company ploy.

Neuroskeptic has excellent coverage of the recent headline-making study on the genetics of ADHD that was overly-hyped as the 'first direct genetic link' to the disorder and overly-slammed as a drug company ploy.

For example, BBC News has a report on the study where you can see researcher Anita Thapar making some unrealistic claims for the significance of the interesting-but-preliminary study while the science-retardant child psychologist Oliver James counters by cherry picking evidence (and not even very accurately).

Neuroskeptic does a great job of untangling the actual import of the research and discusses why the finding of copy-number variations or CNVs in about 16% of the ADHD kids compared to 7.5% of the controls is neither a 'direct genetic link' nor evidence against the idea that the condition is 'socially constructed'.

However, I was particularly drawn by Thapar's comments that discovering the genetic component "should address the issue of stigma."

The common idea is that if we can demonstrate a particular mental disorder is a 'brain disease' or the result of a biological dysfunction people who have the condition will be less stigmatised due to a vague notion that their behaviour 'is not their fault'.

Unfortunately, studies to date have shown that biological explanations for mental disorder actually increase stigma in public, patients and mental health professionals because the affected people are typically seen as more unpredictable and dangerous than when social or psychological explanations are given.

It is genuinely important that we understand the genetic influences to behavioural problems, including those that get classified as ADHD, and this new study is a small but important step toward that aim.

But we kid ourselves if we think this evidence automatically decreases stigma and we do society a disservice if we make our acceptance and compassion for people with behavioural difficulties dependent on certain types of scientific explanation.

Link to excellent Neuroskeptic piece on genetics and ADHD study.

2010-10-01 Spike activity

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

The science of choking under pressure is discussed in a brilliant piece on Neuron Culture.

New Scientist has a debate on whether psychoanalysis should have a place in London's Science Museum. Although getting science in London's Freud museum would be the real challenge.

The performance of young children on the 'mirror self-recognition test' varies hugely across cultures, according to an bull-in-the-china-shop study covered by the BPS Research Digest.

TED has a great talk from neuroscientist Sebastian Seung on the 'connectome' – the project to understand the brain's 'wiring diagram' and what it means. Quite speculative in places but good fun.

Macho financial stereotypes affect female financial behaviour making women more risk averse. An intriguing study looking at how 'stereotype threat' impacts on economic behaviour elegantly covered by Not Exactly Rocket Science.

The Wall Street Journal has an article on ambivalence. Not too bad.

The idea that the time in the womb is one of the most powerful shapers of your life hits Time. See the essential background from Neuroanthropology.

Wired Science covers the under-researched area of group intelligence, finding that emotional awareness, not individual intelligence, contributes most to group problem-solving power.

A fascinating study explaining why self-touch on the site of an injury reduces pain but a touch from someone else on the same spot can be excruciating is covered by Nature's The Great Beyond blog.

The Independent has a good piece on 'blindsight' patients who are consciously blind who can be avoid obstacles.

To the bunkers! Largest ever swarm of flying robots takes to the sky. Wired UK pre-warns us of the threat from above.

A cherry picking lesson from Big Pharma, via Neuroskeptic.

The New Yorker has a big Malcolm Gladwell article on online social networks and damp squib activism. Don't take without two fantastic commentaries: one from The Atlantic and another from The Frontal Cortex.

A first translation of the 18th century French Royal Commission Report on 'animal magnetism' (i.e. 'mesmerism') is covered by Advances in the History of Psychology.

Time asks why do heavy drinkers outlive non-drinkers?

Every time you reach for something, there's a squabbling match in your brain, according to a study covered by Not Exactly Rocket Science. Often, my brain keeps squabbling afterwards.

Discover Magazine has a short piece by Oliver Sacks on his hopes on how neuroscience will develop in the next thirty years.

There's a fascinating look at life and ideas of prison reform theorist Kenneth Hartman over at In the News. Unlike most other thinkers in the area, he's currently serving life.

The Lancet has a fantastic piece on the psychology of selecting medical students to be good professional doctors. Science grades, it turns out, count for shit.

Fulfilling your child's desires may help them understand those of others. An intriguing study covered by Evidence Based Mummy.

Slate has a fascinating piece on the history of male-female friendships, noting that before the 20th century, friendship was single-sex.

A new World Health Organisation report on mental health and mental illness in the developing world is covered by Providentia. "…over 80 per cent of people in need have no access to psychological or psychiatric treatment".

New Scientist has an excellent piece on how handbags are flying over the science of evolved altruism.

Our brain connections become more sparse and sharp with aging. Deric Bownds' MindBlog covers a new scanning study on inevitable decline – has some lovely images.

BBC News reports that US executions are delayed because of a nationwide shortage of sodium thiopental.

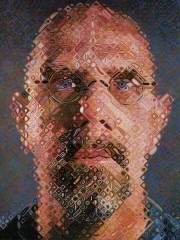

Visual science in the art of Chuck Close

I've just found this amazing article on the work of artist Chuck Close from a 2008 edition of the Archives of Ophthalmology.

I've just found this amazing article on the work of artist Chuck Close from a 2008 edition of the Archives of Ophthalmology.

It examines the visual science behind his pixelated style and how a stroke left the artist paralysed – after which he has produced some of his finest work.

Chuck Close (1940- ) is one of the most famous American artists working today. His distinctive paintings are huge canvases that depict faces, often his own. He works in a nontraditional manner by combining many small geometric forms, usually squares or rectangles, to create a portrait. The individual elements he uses in making an image may be termed pixels. The word pixel is a neologism used in computer technology to mean the smallest form in a digitized image and is a combination of the words picture and element.

Chuck Close is a compelling individual who has endured a great physical misfortune. In 1988 he experienced an occlusion of a spinal artery in the neck, which left him quadriplegic. The occlusion has affected the way he paints, but not his style of painting. Many experts have found it difficult to differentiate work done before the onset of his quadriplegia from that done afterward.

The paintings lead to important questions concerning visual perception and the possibility of artificial vision. What determines our ability to combine many small geometric units into a coherent image? How many different elements are needed to create an image? What are the effects of changing colors within the elements?

Close has had a long interest in science, and even painted a cover for the journal Science.

For someone who paints such remarkable portraits, you might be surprised to learn that he recently revealed he has prosopagnosia, a life-long difficulty in recognising faces.

The Archives of Ophthalmology article looks at how we perceive coherent images from patterns that seem chaotic when viewed at close quarters and how Close takes advantage of these processes in his work.

You can click on the images in the article to see them much larger and really get an idea of how they're constructed.

Link to Archives of Ophthalmology on Chuck Close and visual science.

September 30, 2010

Hypnosis in the lab: the suggestion of altered states

I've got an article in The Guardian online about how hypnosis is being increasingly used in the neuroscience lab to simulate unusual mental states and alter the normal flow of automatic psychological processes.

I've got an article in The Guardian online about how hypnosis is being increasingly used in the neuroscience lab to simulate unusual mental states and alter the normal flow of automatic psychological processes.

After years of neglect, it turns out hypnosis is a useful experimental tool that allows temporary changes to both the conscious and unconscious mind that are normally very difficult to achieve.

Whenever AR sees a face, her thoughts are bathed in colour and each identity triggers its own rich hue that shines across her mind's eye. This experience is a type of synaesthesia which, for about one in every 100 people, automatically blends the senses. Some people taste words, others see sounds, but AR experiences colour with every face she sees. But on this occasion, perhaps for the first time in her life, a face is just a face. No colours, no rich hues, no internal lights.

If the experience is novel for AR, it is equally new to science because no one had suspected that synaesthesia could be reversed. Despite the originality of the discovery, the technique responsible for the switch is neither the hi-tech of brain stimulation nor the cutting-edge of neurosurgery, but the long-standing practice of hypnosis.

As it turns out, our scientific paper on the cognitive neuroscience of hypnosis and the 'hysteria' has also just been published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

'Hysteria' is the traditional name for an interesting condition now often diagnosed as 'conversion disorder' where people are paralysed, blind, have seizures or show other seemingly neurological problems without any evidence of nervous system damage that could explain the problem.

The 19th Century French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot proposed that hypnosis and hysteria might work in a similar way – brain circuits outside of conscious control might be inhibiting or 'shutting down' other functions.

The idea was dismissed for many years, but we review neuroimaging and neuropsychology studies that suggest he might have been on the right track and something similar may explain why people can seem to lose conscious control over their body and senses during both hysteria and hypnosis.

The Guardian article explores the use of hypnosis in neuroscience more widely, how it is becoming an important experimental tool, and dispels some of the common myths about the effects.

One of the problems with researching or using hypnosis in the lab is its association in popular culture with quacks and stage hypnotists, which means many scientists give it a wide birth as they did with consciousness research a decade ago.

You'll notice the piece has been given an odd title and a cheesy picture which I suspect is similar to how articles on consciousness are typically accompanied by a picture of a brain flying through space.

Link to Guardian piece on hypnosis in neuroscience.

Link to abstract of paper on neuroscience of hysteria and hypnosis.

September 29, 2010

I've got a cAMP that goes up to 11

Eric Kandel, push that Nobel Prize to the back of the cabinet. Your work has inspired a song by Canadian death metal band Neuraxis.

Eric Kandel, push that Nobel Prize to the back of the cabinet. Your work has inspired a song by Canadian death metal band Neuraxis.

The track is called Imagery from the 2002 album 'Truth Beyond…' Sadly, I can't find any audio of the piece online, but if you want a taster of what the band sound like, get someone to repeatedly drive a tank into a guitar shop, or click here.

Presumably the band have a long-standing interest in neuroscience as they are named after the layout of the central nervous system.

Anyway, here are the lyrics to Imagery, which reference Kandel's work on the neurobiology of memory:

Imagery by Neuraxis

Striving… Memories. Striving… Memories.

Aplysia's sensory neurons, alter response level to a given stimulus based on action transpired.

Protein synthesis; Involved in learning.

The strengthening, weakening of synaptic connection; The cellular basis of memory.

All thoughts and feeling; Euphoric or bizarre.

Results of endless interactions of neurochemicals.

Altered perception, re-altered beliefs, affects the mind, the thought process.

Endless emotions, infinite dreams.

Endless emotions, infinite dreams.

Affects the mind, the thoughts patterns.

This machinery called imagination.

Weaves an intricate.

Web of imagery… Imagery.

This machinery called imagination.

Weaves an intricate.

Web of imagery…

Imagery.

Link to Wikipedia page on Neuraxis.

Doyle's father, Sherlock's first portrait artist, seized

A brief piece on Charles Altamont Doyle, father of the famous Sherlock Holmes author, from an article on artists and epilepsy just published in Practical Neurology.

A brief piece on Charles Altamont Doyle, father of the famous Sherlock Holmes author, from an article on artists and epilepsy just published in Practical Neurology.

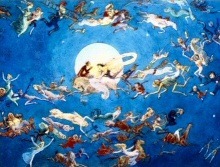

Probably more famous as the father of Arthur Conan, Charles Altamont Doyle (1832–1893) was said to have epilepsy for the last 10–15 years of his life. The cause on his death certificate was epilepsy of 'many years' standing. He was not a particularly successful artist and perhaps is best remembered for his illustrations that accompanied the Sherlock Holmes novel A Study in Scarlet (1888). Charles was another depressive, but he chose to self-medicate heavily with alcohol. It is possible that his seizures, occurring late in life, were related to his consumption of alcohol and rapid withdrawal. He was committed to the Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum in 1881, where finding peace at last, he created some of his best work. It is said that he persevered with his art in an attempt to show that he had been wrongfully imprisoned in the institution; ironically, the recurring themes that he used to plead for his sanity were elves, fairies and other fantastical characters [above]. It is said that he died during a prolonged seizure.

Charles Altmont Doyle is best known for the picture above, named 'A Dance Around the Moon', although my favourite is one from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London who have a self-portrait where he is surrounded by devils, demons and a levitating woman.

Rather than looking terrified or wallowing in self-pity, he just looks fed-up.

Link to PubMed entry for article on epilepsy and art.

Link to Charles Altmont Doyle self-portrait at the V&A.

The murder club

I'm a bit embarrassed to say that my latest Beyond Boundaries column for The Psychologist was published last month and I managed to miss it.

I'm a bit embarrassed to say that my latest Beyond Boundaries column for The Psychologist was published last month and I managed to miss it.

It's about how murder is one of our most social acts. Think of it as like your local community cake sale, but for killing.

Murder is not antisocial. If you want a demonstration that we are governed by society even when breaking its rules, homicide is one of the best and grimmest examples. Studies show that victim and offender tend to resemble each other to a striking degree – the young murder the young and the old murder the old, rich and poor rarely kill each other, gang bangers prey on other gang members, and you are likely to be personally acquainted with the person who later ends your life. Socially conservative it may be, but homicide remains a deeply social act.

In a remarkable 2010 study published in the American Journal of Sociology, academic Andrew Papachristos took these findings to their logical conclusion and conceptualised each murder over a three-year period in Chicago as a social interaction between groups. Surprisingly, the pattern of homicides resembled an exchange of gifts. One gang 'presents' a murder to another, and that group must reciprocate the 'gift' or risk losing their social status in the criminal underworld. From this perspective, murder is perhaps the purest of social exchanges as the individual is left in no position to reciprocate on his own.

Murder, is not, however, an equal opportunities reaper and you are considerably more likely to be dispatched if you are poor and marginalised. It was not always the case though. Historical records show that homicide was used equally by all levels of society but has become increasingly less democratic over time as access to formalised systems of dispute resolution have become more widely available. The fact that the legal system is preferentially used by those with money is perhaps not surprising, although the fact the distribution of justice is unjust should give us pause for thought.

Nowhere is this contrast more striking than in Latin America. Although the region has the highest murder rates in the world the generalisation tell us little – the devil is really in the detail. A 2008 study led by the Venezuelan sociologist Roberto Briceño-León found that poverty in the region predicted little of the homicide rate on its own. It was inequality that explained the trend: in areas where wealth and extreme poverty coexist, violence occurs more frequently.

Despite the horror, society adapts and nations with higher levels of slayings have been found to have higher acceptance of murder. If we want to prevent violence we need to understand that murder is not a stain on the fabric of society, it is one of its threads.

Thanks to Jon Sutton, editor of The Psychologist who has kindly agreed for me to publish my column on Mind Hacks as long as I include the following text:

"The Psychologist is sent free to all members of the British Psychological Society (you can join here), or you can subscribe as a non-member by emailing sarsta[at]bps.org.uk"

September 28, 2010

Taking the sponge

A curious case of a two year old infant who had a sponge-eating obsession. The report is taken from a small case series of compulsive sponge-eating in children, published in medical journal Acta Pædiatrica.

A curious case of a two year old infant who had a sponge-eating obsession. The report is taken from a small case series of compulsive sponge-eating in children, published in medical journal Acta Pædiatrica.

Remarkably, the child was successfully and quickly treated just by correcting low iron levels in the blood.

A general practitioner referred a 32-month-old girl with an obsession of eating sponge since the age of 7 months. The obsession for the sponge aggravated to the extent that she could rip the cushions, car seats and mattresses to get the sponge out. The child was noticed to have a strong, irresistible urge and was seen finishing a fifth of sponge from a cushion in less than half an hour. Occasionally she had been seen eating carpet fibres and tissue papers. She was otherwise a fit and medically healthy girl with a normal intelligence and behaviour. The examination including general physical and systemic resulted to be unremarkable except pallor…

The child was diagnosed to be a case of pica with IDA [iron deficiency anemia] and was kept on 4 mg/kg per day of iron. The symptoms of eating sponge disappeared fully by correcting her IDA.

The mentions of "a case of pica" refers to a psychiatric disorder where people feel compelled to eat the inedible.

We've discussed several unusual adults case of pica previously on Mind Hacks, including people who compulsively eat bullets, coins and roofing plates.

Link to PubMed entry for sponge-eating case series.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers