Tom Stafford's Blog, page 121

October 7, 2010

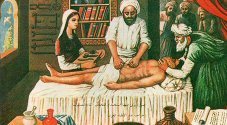

The Arabic anaesthetic sponge

A 1997 letter to the British Medical Journal describes an innovative surgical anesthetic used by Arabs in the middle ages that involved placing a sponge soaked in opium, hashish and scopolamine over the patient's face.

A 1997 letter to the British Medical Journal describes an innovative surgical anesthetic used by Arabs in the middle ages that involved placing a sponge soaked in opium, hashish and scopolamine over the patient's face.

From the ingredients, the patient was probably aware of little, let alone any pain, and it appropriately features in the dreamy Middle Eastern classic, Arabian Nights.

Editor—Anthony John Carter's review of sedative plants skipped several centuries and did not mention the "Arabic anaesthetic sponge." Opium infusion was known to Arab clinicians throughout the middle ages and was used commonly to relieve pain associated with inflammation or procedures such as tooth extraction and reduction of fractures. Poppy seeds were used in oral perioperative analgesic syrups or paste; their boiled solution was often used for inhalation.

Anaesthesia by inhalation was mentioned in R Burton's Arabian Nights, and Theodoric of Bologna (1206-98), whose name is associated with the soporific sponge, got his information from Arabic sources. The sponge was steeped in aromatics and soporifics and dried; when required it was moistened and applied to lips and nostrils. The Arabic innovation was to immerse the "anaesthetic sponge" in a boiled solution made of water with hashish (from Arabic hasheesh), opium (from Arabic afiun), c-hyoscine (from Arabic cit al huscin) [aka scopolamine], and zo'an (Arabic for wheat infusion) acting as a carrier for active ingredients after water evaporation.

Link to full text of BMJ letter.

Dealing with delinquents in the 1920s

Canada's The Daily Gleaner has a brief but revealing insight into the understanding of juvenile crime and delinquent behaviour in the 1920s.

Canada's The Daily Gleaner has a brief but revealing insight into the understanding of juvenile crime and delinquent behaviour in the 1920s.

Obviously the cultural standards of the day were different, so some behaviours considered 'delinquent' then were not be considered so now, and vice versa.

However, it is also clear from the piece that theories of how delinquency came about were influenced by very different sets of assumptions.

Prior to the emergence and expansion of psychiatry, moral and eugenic discourses dominated the understanding of juveniles and their treatment. However, Toronto Mayor Howland and other 19th-century reformers believed "allowing youth to go to the devil was a sheer waste."

They believed there was no "such thing as a youth being really criminal at heart," and that all deviant actions were just "surface depravity."

Children were considered to be the product of their surroundings, and if a delinquent grew up in idleness and crime, that is what any child would be in a similar situation.

Previously, the dominant explanation for juvenile deviance was a 'defective mind' due to an inherited degenerate constitution. Famous at the time were life histories of degenerate families, with their poverty, prostitution, alcoholism and incest.

The brief article also mentions case reports of the time with a short excerpt which seems nothing short of jaw-dropping from a modern perspective:

Amanda, for example, had become "impudent of late" with a tendency to become "foxy and cunning." Physical examination of her hymen showed she "had been immoral," so she was found guilty of vagrancy and sent to the home for girls.

When Amanda was asked by a social worker about her life goals, she said she wanted to be an actress, and the psychiatrist was appalled. He suggested that a better occupation would be milliner, with release conditional on her acceptance.

Link to psychology and delinquency in the 1920s (via @jonmsutton).

October 6, 2010

Campaign man

Wired Science has an exclusive interview with Ari Ne'eman, the first openly autistic White House appointee in history, who has been given a place on the National Council on Disability that advises the president on equality for disabled people.

Wired Science has an exclusive interview with Ari Ne'eman, the first openly autistic White House appointee in history, who has been given a place on the National Council on Disability that advises the president on equality for disabled people.

Ne'eman is an advocate of neurodiversity, which rather than automatically seeing conditions like autism and Asperger's syndrome as diseases to be cured, understands them as another form of human variation that should be accepted.

As a society, our approach to autism is still primarily "How do we make autistic people behave more normally? How do we get them to increase eye contact and make small talk while suppressing hand-flapping and other stims?" The inventor of a well-known form of behavioral intervention for autism, Dr. Ivar Lovaas, who passed away recently, said that his goal was to make autistic kids indistinguishable from their peers. That goal has more to do with increasing the comfort of non-autistic people than with what autistic people really need.

Lovaas also experimented with trying to make what he called effeminate boys normal. It was a silly idea around homosexuality, and it's a silly idea around autism. What if we asked instead, "How can we increase the quality of life for autistic people?" We wouldn't lose anything by that paradigm shift. We'd still be searching for ways to help autistic people communicate, stop dangerous and self-injurious behaviors, and make it easier for autistic people to have friends.

But the current bias in treatment — which measures progress by how non-autistic a person looks — would be taken away. Instead of trying to make autistic people normal, society should be asking us what we need to be happy.

This issue is a particularly heated one, not least because describing someone as 'on the autism spectrum', or even 'autistic' tell us little about the individual.

People with a diagnosis of autism can range from highly intelligent but socially atypical individuals, to people who are unable to attend to their most basic needs and are severely cognitively impaired.

This diversity means that anyone seeming to champion autistic people is assumed by one party or other to be an interloper who doesn't fully represent the range of life experiences, either of individuals or families with autistic members.

Ne'eman is certainly a powerful and articulate speaker and as the first autistic person to be appointed to an official advisory position, he will be seen as the 'voice of autism' whether he likes it or not.

Link to Wired Science interview with Ari Ne'eman.

Drone war psychology

As US military attacks by unmanned drone aircraft intensify, I was interested to find a podcast (mp3) on the psychology of combat drone piloting from Texas Tech University's Psychology Podcast.

As US military attacks by unmanned drone aircraft intensify, I was interested to find a podcast (mp3) on the psychology of combat drone piloting from Texas Tech University's Psychology Podcast.

Unfortunately, their podcast series is not well indexed, but from what I can make out, the piece was from 2007 and interviews aviation psychologist Nancy Cooke and ex-fighter pilot and current drone interface designer Missy Cummings.

The discussion is notable for a couple of things. The first is the interesting point that although drones are aircraft, the designers are trying to stop engineers automatically designing control centres that look and work like aircraft cockpits.

Cockpits are designed to do the best job in the space allowed, and, although familiar, control systems for drones can be much better designed if the whole concept is divorced from the cockpit metaphor.

The second is that they don't mention killing anyone.

I allowed myself a grim smile when Cummings is asked how the drones are used and she replies "search and rescue, for instance, downed hikers in remote areas, border patrols, we can use them to take pictures and that's what happens a lot in Afghanistan and Iraq – they use predatory UAVs to really monitor a situation".

The stress of being interviewed obviously caused 'running an illegal air war in Pakistan' to slip her mind.

Snarky comments aside, the psychology of killing remotely must play a huge role in how the drones are managed in combat, and it's not as if the topic has never been broached.

'On Killing', a book on combat that analyses the role of psychological distance in kill decisions and their aftermath, is a classic in military psychology.

Nevertheless, the podcast is a brief but interesting interview on the psychology of drone flying and how the wider public feel about unmanned aircraft as they inevitably migrate from military weapons to civilian workhorses.

mp3 of interview on drone piloting psychology.

Link to Texas Tech podcast page.

October 5, 2010

The '68 comeback perceptual

Elvis makes a fleeting comeback, accompanied by a milk drinking chimp and some well-dressed mice, in the hallucinations of a patient with Parkinson's disease who is described in the Southern Medical Journal.

Elvis makes a fleeting comeback, accompanied by a milk drinking chimp and some well-dressed mice, in the hallucinations of a patient with Parkinson's disease who is described in the Southern Medical Journal.

He had compulsive gambling behavior and multiple hallucinations (visual and auditory). Visual hallucinations were simple (shapes of shadows, animal shapes like a raccoon, a cat, and a dog) and complex (a woman sitting next to him in car, two well-dressed little mice running around, a chimpanzee drinking his milk standing next to his lunch table in a restaurant, and Elvis Presley standing outside his door in his white coat and white trousers without a guitar). Once while fishing, he saw his dead uncle standing next to him and his uncle said, "It's not going to work." Auditory hallucinations were also both simple (incomprehensible sounds) and complex (like his uncle talking to him, nonspecific symphony, and constant melody of chimes). All hallucinations were associated with intact insight and were nonthreatening.

Although the patient was diagnosed with Parkinson's, which is known to trigger hallucinations, it is likely they were caused as much by the dopamine-boosting medication than by the effects of the disease itself.

The patient was taking quite a selection, reportedly prescribed "a combined regimen including carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg four times a day (q.i.d.); carbidopa/levodopa 50/200 mg sustained release three times a day (t.i.d.) with a half tablet in the morning; entacapone 200 mg 5 times a day; pramipexole 1mg q.i.d. with 1.5 mg at bedtime (h.s.); amantadine 100 mg twice a day (b.i.d.); and clonazepam 1mg h.s."

Despite the perceptual distortions encouraged by the meds, the patient is quoted as saying "It is the best control I have had of my motor functions in a long time" and refused to discontinue any of the treatments.

Link to PubMed entry for case study (via @anibalmastobiza).

October 4, 2010

Whacking off: a psychological history

The Insight Therapy blog has a fantastic dash through the psychological history of masturbation – looking at how self-pleasuring has been linked to everything from madness to blindness and has even inspired a type of biscuit [no, not that type].

The Insight Therapy blog has a fantastic dash through the psychological history of masturbation – looking at how self-pleasuring has been linked to everything from madness to blindness and has even inspired a type of biscuit [no, not that type].

Through the 19th century, the assault on "self-abuse" continued: Reverend Sylvester Graham invented the Graham crackers to curb sexual impulses. In the 1830s, Benjamin Rush, renowned physician and signer of the declaration of Independence, argued that masturbation caused tuberculosis, memory loss, and epilepsy. JH Kellogg, turn of the century medical writer and creator of breakfast cereal, believed signs of masturbation included acne, weak back, and convulsions. Noted 19th century physician and early sex research pioneer Richard von Krafft Ebing linked masturbation to homosexuality and other types of what he considered deviance and illnesses.

The piece makes the interesting point that that the practice is more common in men than women and has been linked to range of positive health outcomes, perhaps suggesting that we should be aiming to include masturbation in the drive to close the gender gap.

Link to Insight Therapy on 'The Maturbation Gap'.

Edvard Munch in 100 words

This month's British Journal of Psychiatry has the latest in their '100 words' series on the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, famous for his iconic painting 'The Scream' and his own struggles with mental illness.

This month's British Journal of Psychiatry has the latest in their '100 words' series on the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, famous for his iconic painting 'The Scream' and his own struggles with mental illness.

The Norwegian Expressionist Edvard Munch caused outrage when his paintings were first shown in Berlin but became one of the most prolific artists of his time. Often described as having had bipolar affective disorder, his low moods and sense of isolation are evident in works such as The Scream, Separation,and Evening on Karl Johan. Yet the evidence of his diaries and his many biographies suggest more plausible diagnoses of depressive disorder and comorbid alcohol dependence. Art historians acknowledge his ability to represent extreme emotional states, while debating the extent to which Munch exploited the market for his 'flawed personality'.

Link to DOI entry for article.

Distracted by the data

Wired has an incisive article looking at the science behind the 'technology and multi-tasking are damaging the brain' scare stories that regularly make the media.

Wired has an incisive article looking at the science behind the 'technology and multi-tasking are damaging the brain' scare stories that regularly make the media.

The piece does a fantastic job of actually looking at specific studies on multi-tasking and distraction and questioning whether the 'tech scare' headlines are warranted given the findings.

The conclusion is neither that 'all is well' or that 'we are all doomed' but that we really have very little data – although none of it so far has given any credence to popular concerns that technology is impairing our intelligence.

The piece also hits on the crucial idea that talking of 'technology' or the 'internet' as a coherent whole is unhelpful because it has such different forms each with potentially different effects:

A solid consensus on digital multitasking is unlikely to be reached anytime soon, perhaps because the internet and technology are so broadly encompassing, and there are so many different ways we consume media. Psychological studies have seen a mix of results with different types of technology. For example, some data shows that gamers are better at absorbing and reacting to information than nongamers. In contrast, years of evidence suggest that television viewing has a negative impact on teenagers' ability to concentrate. The question arises whether tech-savvy multitaskers could consume different types of media more than others and/or be affected in diffferent ways.

A research paper authored by a group of cognitive scientists titled "Children, Wired: For Better and for Worse" (pdf) sums it up best:

"One can no more ask, 'How is technology affecting cognitive development?' than one can ask, 'How is food affecting physical development?'" the researchers wrote. "As with food, the effects of technology will depend critically on what type of technology is consumed, how much of it is consumed, and for how long it is consumed."

There are some quotes from me included, but don't let that put you off, as it remains a lively discussion of the science behind a common 21st century talking point.

Link to Wired piece on media, technology and brain studies.

October 3, 2010

The war changed me: brain injury after combat

The Washington Post has an amazing series of video reports on US soldiers who have returned from Iraq and Afghanistan with brain injury – often leading to a marked change in personality.

The Washington Post has an amazing series of video reports on US soldiers who have returned from Iraq and Afghanistan with brain injury – often leading to a marked change in personality.

The reports cover veterans who have suffered numerous types of brain injury, from shrapnel-driven penetrating brain injuries to concussion-related mild-traumatic brain injury, and how they have adapted after returning home.

The treatments range from brain surgery to psychological rehabilitation and the interviews cover the difficulties from all angles – including the patients', families' and medical professionals' perspectives.

It's probably worth noting that this combat brain injury is not an area without controversy and the Washington Post piece follows the US military orthodoxy on mild traumatic brain injury – that all problems after blast concussion are due to brain damage.

Owing to the widespread use of improvised explosive devices many soldiers get caught up in a blast without suffering any visible physical injury, although they may suffer concussion due to the shock waves.

The US military is focused on the idea that subsequent problems – such as headaches, mood problems, trouble concentrating, irritability, impulsiveness or personality change – are due to the physical effects of the blast. This cluster of symptoms is often diagnosed as post-concussion syndrome or PCS.

Studies have found that, on average, soldiers who have experienced a blast are more likely to show changes in the micro-structure of the brain. However, not every soldier who shows the PCS symptom cluster has detectable brain changes or shows a clear link between the symptoms and the blast.

This latter point is important because the same symptoms can arise from combat stress – being caused by the emotional impact of war rather than a direct result of a shock to the brain.

It becomes clear why this distinction is crucial when you read the US military's guidance on screening for mild traumatic brain injury which doesn't have a specific way of distinguishing the effects of emotional stress from the effects of brain disturbance.

Owing to the fact that blasts are such common experiences for soldiers, this could lead to false positives where veterans are thought to have brain damage when they would be better off being treated for combat stress.

In fact, this exact same scenario was played out in World War I where 'shell shock' was originally considered to be caused by blast waves affecting the brain (hence the name) only for it to be later discovered that not everyone who had the symptoms had even been near a shell explosion.

Regardless of this medical debate, The Washington Post special report is a fantastic combination of real life experiences and the neuroscience of combat-related brain injuries. Highly recommended.

Link to WashPost 'Coming home a different person' with intro clip.

Link straight to main menu.

Rehabilitating the most vilified

ABC Radio National's 360documentaries has a confronting edition that interviews two child sex offenders currently in treatment along with their psychologist, examining their offending behaviour, what led up to it and what they hope to change in their lives.

ABC Radio National's 360documentaries has a confronting edition that interviews two child sex offenders currently in treatment along with their psychologist, examining their offending behaviour, what led up to it and what they hope to change in their lives.

It's neither morbid sensationalism nor an apology for crimes committed but there are plenty of moments that don't make for easy listening.

It does, however, challenge lots of stereotypes about the sort of person who undergoes treatment in such a programme as the two people involved are very different – one of which has never actually committed a personal offence against a child but who sought treatment after struggling with his desires.

The programme is a rare look at the sort of treatment programme that is often vilified by the press, despite strong evidence that such programmes reduce offending and keep the public safer as a result.

There are a few places in the piece that I thought could have been done better, but in general, it's unlikely you'll get a more stark insight into a difficult and controversial area.

Link to 360documentaries on sex offender treatment programme.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers