Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 93

April 16, 2013

Amy Brill talks about The Movement of Stars, the first female astronomer, what's love got to do with it?, fave chocolate bars, and so much more

Amy Brill's written the kind of novel you are going to find yourself giving to friends because you want to discuss it with them. A Pushcart Prize nominee, she's been awarded fellowships by the Edward Albee Foundation, The Millay Colony, the Constance Saltonstall Foundation, and more. A broadcast journalist, she's received a George Foster Peabody Award for writing MTV's The Social History of HIV, and she's researched, wrote, or produced many projects for the network's pro-social initiatives. I loved her novel and I'm deliriously happy to have her here. Thank you, Amy!

You said you were inspired by Maria Mitchell, the first female astronomer in America. The book is also set in 1845 Quaker Nantucket and involves whaling. All of these facts absolutely mesmerize me. What was your research like and what took you by surprise?

Well, since I picked a time, place, subject(s), religion, and occupation(s) about which I knew absolutely nothing (note to aspiring novelists: do as I say, not as I did), the more I learned, the more I felt I needed to learn. The research was sometimes a trap, especially because it was my first book. I more or less gave myself a PhD in mid 19th century maritime New England women’s studies, while conveniently avoiding the real work of writing a novel.

The biggest surprise, research-wise, turned out to be essential to the story. When I asked a librarian at the Mitchell archive on Nantucket for journals and letters written when the astronomer was a young woman, she said there were none: Maria Mitchell burned her own papers and diaries in her fireplace during the “Great Fire” of 1846. A third of Nantucket Town burned that night, and people’s private papers were being blown around, so she destroyed hers. I think I just stood there and stared at her, speechless, my writer-brain firing on two fronts. Firstly: Great Fire. What more do I need to say about that? That turned into one of my favorite scenes in the book to write, and one of the most challenging. Secondly: What was she hiding? In that moment, the character of Isaac, and thus the novel that became The Movement of Stars, was born.

So much of The Movement of Stars is about what we will do for what we love, even when the world seems against us. Could you talk about that a bit?

What’s love got to do, got to do with it? I’ll tackle anything that channels Tina Turner. Following one’s passion almost always requires some kind of sacrifice, be it leisure time, or family time, or the pursuit of other endeavors, or of other people, or of money, or of fame—unless fame is your passion, in which case it is statistically likely that you’re wasting your time. Anyway... Hannah sacrifices almost everything in pursuit of her comet, but she is deaf to the music of her heart. She takes a slow road to self-awareness, and since it took me 15 years to finish the book, I took that journey along with her. And by slow road, I don’t mean sluggish, I mean glacial. When I began the book I was single, in my twenties, and searching for both love and my writing voice. When I finished I was married, over forty, and the mother of two very young daughters. I understood her journey quite differently by then. The twin engine of love is discipline. Especially when it comes to surmounting obstacles, be they political, creative, intellectual, or even emotional. You have to carry on, push forward, keep working. Love alone is not enough. I think Hannah taught me that.

I'm always fascinated by process, so can you tell me about yours? Do you map your novels out or go by inspiration?

Oh, I’ve tried everything; mapping, outlining, postcards, winging it. Inspiration is wonderful, but it’s only a leaping off place, an essential spark. After that it’s a hard slog through the swamp. A little bit of structure does go a long way toward getting me started, though; if I know, say, where a story is going, or what happens in part one, part two, part three, that really helps me get off page one and go forward, which is really the only direction you can go if you hope to finish a novel.

This is your debut, but I read that you first came upon the home of Mitchell 15 years ago, which sparked the idea for the book. Can you talk about how that idea crystallized into the novel?

I first learned about “Miss Mitchell” on a day trip to Nantucket in 1996 (see: glacial pace, above.). I loved the idea of a young woman, a teenager really, up on her roof, searching the sky night after night for something that would change her life. Plus an isolated island, a rigid religious community, whaleships, a country expanding yet divided... what a story! I convinced myself I had to hew unswervingly to the facts of her life, to get it “right”—but in doing so I hamstrung my story. I only realized it when Iberia lost my whole backpack of research, in 2006. (I’m still waiting for the reparation money they promised and never delivered.) After a long break from the novel during which I licked my wounds and whined, I reread what I’d written and realized that I wasn’t telling the story I wanted to tell, which was inspired by Maria Mitchell but not about her. When I started again, I was writing The Movement of Stars.

What's obsessing you now and why?

I’m really into writing short stories again, which feels like a post-novel restorative of sorts. But I’m already turning over a couple of new ideas for longer investigation that I can’t seem to let go of. I’m squirrely like that. I turn an idea over and over and store it in my tree or my cheek or my heart until I’m ready to dig in.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

If you were stranded on a desert island and could only have one chocolate bar, what bar would it be? I’d have to say that it’s a close contest between Mast Brothers Maine Sea Salt and Equal Exchange Organic Dark Chocolate with Almonds. Can’t have the sweet without the savory.

Published on April 16, 2013 08:30

April 9, 2013

Luanne Rice Talks about The Lemon Orchard, being drawn to places, changing the brain's wiring, and so much more

Every time writers get together, we end up talking about other writers we love--and Luanne Rice's name keeps coming up in the conversations. The author of 31 novels, including 22 consecutive New York Times bestsellers, she's had her work turned into plays, movies and mini-series. Her new novel, The Lemon Orchard is about compassion, love, and the way we can navigate our way through pain. I'm thrilled to have Luanne here, and Luanne--coffee in Chelsea is on me! And we need to have pie, too.

You are the beloved and acclaimed author of 31 novels, which makes me breathless just to write that. Did you always know you were going to be a writer? (I want to reference your great essay in What My Mother Gave Me (Algonquin). What's your writing life like? And how has it changed through the years?

Beloved! Thank you. I’ve always wanted to be a writer. The desire began when I was young, and probably in an unconscious way—I preferred to live in stories than real life. I read constantly, in a sliver of light from the hallway after bedtime, and regularly missed over half the school year from first grade through twelfth. My family was complicated, and I was afraid that if I wasn’t home it would fall apart. I read and wrote while home from school, and kept my ears open for signals of what was going on in our family; I’d sit upstairs and write stories in which everything turned out well and happily. Family troubles have always pierced my heart and therefore inspired me, and that has old roots.

My mother encouraged my writing. She wrote herself—she had a play produced while in college, short stories published in the Saturday Evening Post and the American Magazine, and after she had three daughters wrote into the night after she’d put us to bed. The sound of her typewriter was our lullaby. When I was eleven she sent a poem of mine to The Hartford Courant, and it was published in the poetry column. Somehow that gave me the idea that all one had to do was write something and it would appear in print.

Years later, when I dropped out of college to write I realized how hard it was to get published. The stack of rejected short stories grew tall on my desk—I’d get really nice notes from Mimi Jones at Redbook and initialed rejection slips from The New Yorker saying, “Try us again.” My first acceptance was by Ascent, the literary magazine at the University of Illinois, edited by Dan Curley. He was so kind and generous.

My writing life is very solitary, an excuse to be a hermit. I get up early and have a talismanic need to be at my desk before speaking out loud. I write till I’m hungry, take a break, sometimes take a walk, then get back to work. I use my dreams, terrors, obsessions, and loves as material. Often my writing revolves around family or ruined love. My main character is usually a woman about my own age although any resemblance to anyone alive or dead is purely a coincidence.

The Lemon Orchard explores how we can and should connect through pain--and it does it in a very beautiful way. Can you talk a bit about that, please?

The Lemon Orchard is set in Malibu California, where I moved after living over half a century in the northeast. I can’t adequately explain it, even to myself. Sometimes I panic over the whole thing. My whole family is back east. I still think of myself as a New Yorker—I’ve had a place in Chelsea forever and I love New York. Most of my best friends are there. But I always crave nature and the ocean, and I have a Buddhist respect for detachment, so maybe it was time to leave everything that was familiar and move to a new ocean and write about something new. Place figures so predominately in The Lemon Orchard. Are you yourself drawn to certain places, and if so, why?

I am so drawn to places. Settings in fiction make me want to visit—this goes back forever. My family took us to Chincoteague and Assateague on my fourth grade spring vacation, because of loving Misty and the Marguerite Henry novels so much. I lived in Paris for two years and still seek out novels that evoke that city for me. My grandparents had a beach cottage on the Connecticut shoreline, and my imagination gets pulled back there over and over. Malibu is interesting—I think many people imagine it as Celebrity-Central, glitzy and fancy. A lot of actors do live here, but what draws me, and fuels The Lemon Orchard, is the wilderness and extraordinary natural beauty. Malibu sits at the edge of the continent, bounded by the Santa Monica Mountains and the Pacific Ocean. Driving along Mulholland Highway you see vineyards and canyons, and you might think you’re in Italy. I have one very old lemon tree in my yard, so that inspired an entire orchard. Hawks ride the canyon thermals, owls hunt the hillside at night, and during the spring California Gray Whale migration, I can stand at the edge of my yard and see mothers and calves swimming north.

Your work has been made into movies, plays and mini-series. Do you think one form is better for a novel than the other? Have you been happy with all of the translations of your works into other forms, or do you feel it's always a slightly different work?

I feel very lucky to have had TV movies made from my work. Once I write something, it’s out in the world, and if the story becomes a movie, then it becomes something entirely different—in each case the script was written by a screenwriter, not me. I’ve enjoyed the process, and love visiting the sets, getting to know the writers, producers, directors, and cast. Some of them have become good friends. I sometimes have holidays with the family of an actor who appeared in one of the movies. I love the theater. When I was nineteen, my mentor was Brendan Gill, then the drama critic of The New Yorker. Like me he was a Connecticut transplant to New York, and he gave me two very good bits of advice: go to Central Park for nature, and see as many plays as possible. I was a starving writer, and he was very generous with tickets. Since then I’ve had a passion for theater and was so thrilled to have a monologue in Motherhood Out Loud, a play that’s been performed off-Broadway, at the Geffen Playhouse in LA, and at regional theaters. You have a reputation of being one of the kindest writers around.

Wow, thank you. I love my readers and my writer friends, so that makes it easy.

What's obsessing you now?

Oh, my obsessions. Sisters, best friends, family, secrets, owls, protecting the environment, Mexico, immigration as a human rights issue. The Lemon Orchard was inspired by my friendship with an undocumented worker from a small village outside Puebla, Mexico. I’m also obsessed with a book called Mindsight, by Dr. Daniel Siegel. He is a psychiatrist at UCLA and writes about awareness and mindfulness, how one can work with one’s own internal world to change the brain’s wiring. It’s shockingly wonderful, and very helpful in terms of depression and healing trauma.

What question did I forget to ask that I should have?

Just, “when are we having coffee?”

Published on April 09, 2013 18:07

Cameron Stracher talks about Kings of the Road: How Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers and Alberto Salazar Made Running Go Boom, how running has changed, why caffeine is so important and so much more

I first met Cameron Stracher through the Author's Guild. I needed legal help and the Guild sent me to him. After he solved my legal woes in about ten minutes (I will be forever grateful), I discovered, a few days later, that he was also a mind-bendingly terrific writer. A graduate of Harvard Law School and the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he's the recipient of a 1998 fiction fellowship from the New York Foundation of the Arts and the author of a novel, The Laws of Return, and his newest book, Kings of the Road, about three men who changed the world of running, is fascinating. I knew I wanted to talk to him about his book on my blog. Thank you so, so much, Cameron! I'm honored to have you here.

I was so surprised to learn that running has not always been a huge sport in America. Why did America embrace it? And why and how did running hook you?

I think the running boom happened just as the US was transitioning from the hippie 60's to the go-go 80's. It was the perfect sport to straddle both periods because it celebrated freedom and an iconoclastic lifestyle, but it also required tremendous discipline and a narcissistic devotion to the body and self. It hooked me (as it hooked Shorter, Rodgers, and Salazar) because I discovered I was good at it (when I won the 880 yard run in gym class in 8th grade) and for a teenage boy trying to find himself, it gave me something I could feel good about.

The book was an addictive read, especially as it centered on the three pivotal players who transformed distance running: Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers and Alberto Salazar. Shorter gave up a promising med career to run; Rodgers (my favorite) had his life fall apart until he turned to running, and Salazar just knew he would make it big in running--and he did. Would you say that these three very different personality traits probably would have made these men succeed no matter what they chose to do, or do you think it was particular to running, and if so, why?

It was one of the great puzzles to me as I wrote the book: What common feature did these three different personalities share that made them all great runners? The cerebral Shorter, the "flakey" Rodgers, and the glowering Salazar? What they shared, however, was an intense competitive drive. When they ran, they were completely focused on running and drove themselves to ignore pain in pursuit of faster times and victory. I think for Shorter and Salazar that drive would have led them to succeed in most anything they tackled, but I think for Rodgers it was very running specific. In a sense, running saved him and gave him a focus that his life was missing at the time he started competing.

Why and how has running changed? And do you think it's for the better? What are we missing?

Running has become more social for the masses and less social for the elite athletes, which has been both good and bad. More people than ever are running, in large part because running organizations have turned it into a social experience. At the same time, elite athletes train mostly on their own and have not been able to duplicate the success of Shorter, Rodgers, and Salazar without companions to push them.

What was the writing like? What surprised you about it?

Trying to get into the heads of other people is very difficult. You want to be accurate and fair, but you also want to tell a story. I tried very hard to do both. I think I was surprised by how difficult it was.

You're also a talented lawyer. How do you find the time to write?

Caffeine and discipline. I learned (at Iowa) to make writing a "job" and get myself up early in the morning to do it, no matter how I'm feeling. I'll start writing at home before my family is awake, and then continue while on my long train ride into NY (about 70 minutes). Once I arrive in Manhattan, if I'm lucky, I will have done 3 hours of writing. As soon as I step off that train, however, I change back into a lawyer.

You also run--did writing the book change anything about your running, or how you feel about it?

Writing the book made me painfully nostalgic for the days when I was fast. I remember Frank Shorter telling me that the thing he missed the most, now that he was older, was running fast on the track, which he could no longer do. I completely understand how he feels. The freedom and power and strength that comes from barreling down the track while doing a workout with 5 or 6 other runners is something I can no longer do, and I miss it every day.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Because my book was published today, I'm obsessed about its ranking on Amazon and its reviews. I wish I could ignore all this "noise," but I can't.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

What's next? I've got two fiction projects that I'm working on (a young adult novel and a humorous novel). Kings of the Road was my first real book-length work of non-fiction, and I'm looking forward to getting back to fiction for a while.

Published on April 09, 2013 17:57

Rob Roberge talks about his knockout novel The Cost of Living, eating foods in the right color order, redemption tales soaked in acid and so much more

When Gina Frangello (editor and co-founder of Other Voices Books, plus the most amazing author of Slut Lullabies and an astonishing new novel coming from Algonquin Books) tells me to read something, I always listen. The Cost of Living by Rob Roberge is unlike anything you've ever read before. Gritty, crackling, alive--it's the story of a guitarist who fights to stay clean and sober, even as he battles his inner demons. Gina was right--the book's a marvel, and I'm thrilled to have Rob here on my blog. (And I'll be reading with him and host of others at KGB on June 2! Please come!) Anyway, thank you Rob for being here.

What I loved so much is that your book boasts high praise from musicians as well as authors (and you're a musician yourself) for the knockout gritty authenticity of the book. Is there a difference for you in terms of music and writing? Does one feed a greater part of the soul for you, and if so, why?First, thank you so many of the kind and generous things you've said about the book/my writing—and your generosity, both here and with other writers. It's enormously appreciated what you do for the community. I was pretty thrilled, actually, by the response of the musicians, all of whom I respect a great deal, so it was truly an honor to have them saying such nice things. And while I am, I suppose, a musician (in the literal sense—a musician being one who plays music), the four musicians who praised the book—Steve Wynn, Wayne Kramer, Scott Shriner, and Billy Pitman are real musicians. People in bands and solo artists who've had a lasting social impact. I mean I've played 30 years. I've recorded. I've toured. But, I'm hardly in their league so…yeah…it knocked me out that these people had such things to say—especially saying that the work was authentic. In the music sense/the professional sense. And of course that they were entertained. That meant a lot to me.As far as music and writing—the differences…does one feed a greater part of the soul? I suppose if I HAD to give up one (a terrible scenario), it would be the music. I LOVE both tremendously. One of the fun things about this book was that some friends and I made a record performing AS the band in the book. It's available for free download at my new website: www.robroberge.comBut being a writer is simply who I am and what I do. Though I suppose I'm a musician, too…I play 1-3 hours a day most days…but it's mindless. It's not practice the way a serious pro would approach his/her instrument. It's relaxing. Writing is NOT relaxing, much as I love it. I do music for fun with friends. I'm too old to be in a van with a bunch of guys who after two weeks on the road have devolved to the point that they may as well be zoo monkeys who fling their shit at one another. Those days are long gone for me. Though I still LOVE touring. I just tour with people who make for a tension-free experience. The Urinals—John Talley Jones and Kevin Barrett—are two of the funniest, smartest people I know and they are a ball to be out on the road with. Music's also where I fill my need for collaborative art—like theater used to do for me. But I'm not trying to be a rock star anymore—that's been gone from my goals for over 20 years. A young person's game. I'm doing it for fun. Whereas, I AM trying to advance my writing career and I always am challenging myself to be better with each book and try to do something I've never done before. If a song's not as close to perfect as I can get it, but the energy's good…hey, that's good enough for me. I like the happy accident of collaboration and playing with friends. When I work on my writing, I'm very open to the happy accident in the early drafts, but I'm ruthless with myself on revision. I want to be the best writer I can possibly be. I want to have the most fun I can possibly have playing music. Not that I have any interest in putting shit in the world musically.Of course…a lot of my early days of playing in bands were days where I was swimming in liquor and nodding out on various opiates and whatever else I could get my hands on. I lost over a decade of my life being fucked up—daily—and I'm lucky to be around. Being the non-stop fuckup doesn't make you the most fun guy to be locked in a van with for weeks at a time.Though, for the record, I never did fling my shit at anyone. One last very odd difference between the two forms is that I recently played a show where a very attractive younger woman (maybe thirty) was dancing in the front row all night, looking at me. Not the worst thing for your ego. And when the show was over, I was drenched in sweat (the lights on stage are hot) and she took the set list off the stage, asked me to sign it and then asked if she could lick the sweat off my chest. I told her my partner probably wouldn't be too thrilled about that. We ended up with a compromise and she licked the sweat off my arm. It was…odd. This almost never happens when I do a reading. And by almost never…I mean never. Jeez…I hope I've answered your question.The novel's a redemption tale, but it's one soaked in acid and told in a raw, hilarious and deeply original voice. In fact, you've been accused of writing "dangerous" stuff. I'd love to hear your take on that. I'd also like to ask, do you think there is always a cost on the way to redemption?Shit…again—thanks for the kind words. They mean a lot coming from a writer of your caliber. And I'm enormously grateful you mention the humor. It's a dark book in many ways, but I try to balance that. If work is relentlessly dark, it can be oddly simple. You need light to see shadow—light actually makes the darkness more harrowing for me. To be only dark is as one dimensional as a hallmark card. The world is both beautiful beyond belief (and surely love and laughter are at the top of that list), AND it's an ass kick and a half and it can rip you to pieces and make you want to eat a gun at times. So, my acid and my humor…they come kind of naturally, I guess. A world view. If it's cool, I'll answer the cost of redemption issue first—that it's a redemptive tale. And…it's simultaneously the saddest book I've written, the most autobiographical AND the only redemptive narrative I've probably ever done. So, that's a little new to me-ha!I suppose from both its religious and the secular definition, redemption is about settling a score—an evening up where you balance the scales with an effort on your part to make up for earlier mistakes. So, in the literal sense, I suppose redemption has a cost. You know…in recovery, one of the things that helps me stay clean is helping other people and trying very hard to be a much more ethical person than the man I was. I owe the world some good years…though, as junky drunks go, I was a pretty sweet one. That doesn't mean I didn't hurt an awful lot of people who loved me. So…well, a LOT of things/behaviors in this life can't be redeemed. And it's taken me some tough years to realize that. So, you go forward and try to be good from now on. There are things you—or I—just simply can never fix. And I'll have to live with that. But maybe if I can be a better person…well…I don't know if that settles my debts. But, what are the other options?It's part of the price of trying to be a better person. So, yeah…if there IS such a thing as personal redemption, it probably has a cost. As far as being "dangerous"…I've been called dangerous? By whom? It must have been someone afraid of the air. And cookies. And tiny woodland creatures. I'm a teddy bear. A vulgar perverted one, maybe, but still…More seriously—I'm not sure, sadly, a writer can BE dangerous in the United States. I've had friends and colleagues from other countries who've been imprisoned for their poetry…we have journalists who've been killed….writers who've had their eyes gouged out by agents of their government. This, of course, makes me wonder if my work could truly be something dangerous to a reader in contemporary American culture. Not that I'd like to be imprisoned or have my eyes gouged out, clearly. But, no…I don't feel my work is dangerous in that sense. But, I do think, on a daily level, that most people are terribly afraid of letting other people (including those close to them) see the truth of what's in their hearts. We've all heard the idea that we only use ten percent of our brain…and I'd say, I think that we may use the same percentage of our metaphoric heart. I think we may use ten percent of our empathy. And a culture that loses its empathy is a dangerous culture indeed. And literature IS the art form that best creates empathy. It's the form where the audience most learns what it might be like to be inside someone else's brain and someone else's damaged and needy heart. We are all, as Hemingway said, broken by this world. And our job, I think, is to help each other survive and try to heal those broken parts.If we think about it this way—if we lose the ability to feel what others feel, we are in a terrible state as human beings. Most of the ways we form the other is because we haven't taken into account that this unknown person or persons has an interior that we would understand were we open to investigating it. Every war is a result of an absence of empathy. The corporate sociopathic behavior of Enron executives…every greedy fuck who stole from people who worked for a living in the 2008 bailout…even every love relationship that ultimately doesn't work is the result, I think, of people not really SEEING each other.To be loved is to be seen. To be understood. And without love, we're fucked. So, maybe that's where redemption partially comes from. Mending that fracture. Seeing each other. I want to ask about the voice, which was as addictive as any substances that find their way in the story. Was the voice fully formed when you started to write or did you have to write your way into it?That's a great question (not that your other questions have been some bucket of shit…they've all been great…I always get a little scared saying "that's a great question"…but that's my neurosis, maybe. If someone tells me my hair looks good one day, my first thought is "has my hair looked shitty all the other days?").But voice is essential to me. I labor over voice a tremendous amount—and making every sentence a good as it can be. I love language—the way words sing and clang and rattle and thrum with and against each other. And/but it does usually take me a while to get INTO the proper voice. It never comes first in my novels. I ALWAYS have to write myself into it. I have no plan. I write a sentence. That sentence offers me opportunity and obstacle and I try to go from there. But it usually takes me months to find the voice of a novel—to write my way into finding it. Stories come much more quickly—sometimes right away. I think about the importance of voice before I think about anything else. I've never planned a novel's plot. I have no idea where I'm going. But that's probably not the case with my next novel, which I'm starting after I finish a memoir this summer. The next novel has at least five POV…my first three novels have been first person and, until THE COST OF LIVING (which covers, I think, well over 30 years in the life of the protagonist Bud), all my novels have had a short time period. The next one covers from the Bikini Island atomic tests (Operation Crossroads, which started in 1946) to the late 1990's. From, as I said, several POV…so, I think I may plan that one out a bit. It's a lot to keep in my head at once. But, still, voice with be, in many ways, the primary thing.I think of voice as character. The main character.Tell me about your writing life? Do you write every day? Do you have rituals? Do you map things out or figure them out as you go along?Nope. Sometimes I wish I could write every day. But I'm a binge writer. Part of it is that I take a lot of pride in my teaching and it's VERY hard to write while I teach…and I teach a lot. I wish I could juggle better. But, so long as I write, I figure I'm doing my job. If I haven't written in 3 months, something is wrong and I feel it itching at me. But every day? No. I have some mental health issues with up and down sides…rapid cycling bi-polar…and this can allow me 72 hour writing stretches. I had my best single day on the memoir a while back 13,000 words…of which about 12,000 were keepers. So…no. Not every day. I certainly admire writers who can. I have days where writing is all I can do—I get too obsessed to stop to eat. I also have days where I'm too depressed to bathe or shave or see any reason to get out of bed and I just pray for the day to end from the second it starts. So, there are upsides and downsides.As for rituals…yes, some. I can't do drugs anymore…but addicts love their rituals. I can only write with one type of pen in my notebook…or one type of mechanical pencil. If I write with another, I try to transfer the notes to the right pen or pencil BEFORE I type them up. If the writing is sucking, I'll dress up. Put on some nice clothes…maybe a suit and some good shoes. Very rarely a tie. Makes me feel like I'm going to work and not just kicking around the house.Other rituals? I also have some mild OCD where I can only eat food in the same order of colors every time. But, that's not about writing. That's just me being crazy.So what's obsessing you now and why?

Wow. I'm not sure. The release of a new book is a bit scary—at least for me. With the fear that no one will give a shit. But I'm trying not to obsess about that. I'm probably obsessing the most about not being able to sleep. I've averaged about two or three hours of sleep for the last ten or eleven days. It's hard not to obsess about being awake when you don't want to be.And I'm not sure I'm obsessing, but I'm REALLY looking forward to teaching in Mexico at OTHER VOICE QUERÉTARO this summer (http://othervoicesmexico.com/). Actually, I guess I am obsessing about that…I've never taught out of the country and I'm doing a fiction and memoir workshop I'm pretty excited about.I'm pretty obsessed with my new memoir and the form of memoir/non-fiction itself (which is a term I kind of hate…like Nabokov said, "memory is a revision")…I'm more interested in honestly and creation than I am in EVENT (since 5 people can witness the same thing and come away with radically different takes)…the way America has fetishized the "real" with so called reality TV (and this has infected our literature). I guess I'm obsessed with the difference between telling A truth and THE truth. And the music of Ike Reilly and Virginia Dare (both AWESOME) and the new season of Mad Men. There are probably other obsessions, but I'm blanking at the moment.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?I don't know….Maybe: Do you ever shut up, Rob?Thank you SO much for this. It's been a pleasure. I hope it was of some use/entertainment. But/and, thank you for the opportunity, Caroline.

Published on April 09, 2013 17:45

Filmmaker James Mottern talks about God Only Knows, Harvey Keitel, Modigliani, me (!) and so much more

I first met James Mottern because he wanted to option Pictures of You. I knew and loved his first film Trucker, a gorgeously haunting film about a woman trucker and the 11-year-old son she deserted years ago, (Rent it. Trust me.I've seen it twice.) so I was thrilled to get have real conversations with James. He's so smart about story, and truly, so cool, too, and his newest film, God Only Knows is a thrillingly brutal crime drama written by Emilio Mauro and starring Ben Barnes, Harvey Keitel, Slaine, Leighton Meester, Toby Jones, Paul Ben Victor, Kenny Wormald and Jay Giannone. I can't wait until it's out so i can see it.

I'm so thrilled to have James here. The only thing better would be to hang out and have some coffee and pie with him. A million thank-yous, James.

Your film Trucker, which won the Nichols Fellowship, is one of my favorite films of all times because of the haunting sensibility. How is your new film God Only Know different? What attracted you to this project? What about the story spoke to you? Did anything about it surprise you?

James: Thank you, Caroline. My approach to TRUCKER as well as my current film GOD ONLY KNOWS, among several things, is to try to draw out the inner lives of the characters, what's really going on inside of them; and sometimes when that does happen in the performance or the shot or scene it can have a somewhat dream-like quality, as if the character in the film might be a real person and they are simply stepping into the movie of their subconscious or inner life, as if the supporting characters might even be figments of the central character's imagination, or at the very least a memory or the notion of a memory. It's a somewhat French technique that Godard the maestro achieves time and time again, and I give it my best shot.

When you are walking around in the day everyone more or less does the same thing physically. The outer life is very often about meals, children, relationships, bathing, work, etc., and even if it is interesting or fun it still takes place within 24 hours and those hours are very often devoted to similar things for all people. But arguably the inner life is endless; it transcends space and time and reason, really. A person's inner life can be quite rich and wide and deep, thrilling, terrifying, maybe bottomless, filled with imagination or memories or desires all banging together into something entirely mind blowing. I mean, walking down Broadway past all the people and if you were to film everyone's inner life you'd probably see a bunch of crazy shit you wouldn't want to know about, but also some things that were beautiful and tender and jaw-dropping. If we could all live our inner lives in the open and watch everyone else's there wouldn't be a dull day ever. And we'd recognize we are all much closer in our hearts than we sometimes want to believe. In some ways film can capture that inner life.

In the end I want the movies to be entertaining and accessible so people can have an emotional connection to them and so I can make more, but I am conscious of the power of subtext. Also, I like a big wide frame and to make the pictures beautiful. So these two films are different in some ways, but my approach is the same.

What's the process of directing a film (for those of us who are clueless). Do you know what the whole film will look like before you start, or do things change as you are making the film? How collaborative is it?

I usually work through visual references of art or photographs. For this new film I used Modigliani's paintings and Brassai's photos. And I do a great deal of scouting myself and let the locations talk back to me, and the look evolves in my mind; the DP and the Production Designer add to the mix, and everyone else involved, really, and it begins to take shape tonally and visually.

I open my heart to the story and recognize those things that touch me viscerally and emotionally. I also engage the actors on theme and tone and listen to what they have to say early on, if possible. Obviously, they have an opinion of the characters they have agreed to play. Each actor brings something special to a character, something only he or she can bring. I try to recognize what that special something is early and work and build off that. There are top-secret ways for me to know what that special something is ;) but I really prize actors and what they can bring.

And then when you start making the film, it talks back to you the instant you shoot that first frame. Every movie has a personality it seems, and the personality reveals itself a little at a time, like a newborn baby; and as you shoot you get to know that personality more and better and help develop it as you would a child; be kind to it, let it sit on your lap, make it stand in the corner and ultimately raise it to go out and make something of itself! :) That's all a little facile, maybe, but those are some highlights. And really what I try to do is open myself up emotionally to all my talent and crew and let them know it is my deepest intention not to let them down and to make something that will stand the test of time. My job is to be the voice of quality and to bring out the best in people. There's no one who deep down doesn't want to make something great, so why not go for it?!

And what drew me to this new project was that I wanted to make a butt-kicking action film with an emotional edge and I think I've achieved that.

I know I've asked you this already, but I bet readers will want to know: so what was it like working with Harvey Keitel?

Keitel doesn't take bullshit and he asks questions he really wants an answer to. He takes his acting seriously; as serious as a surgeon with his hand in your chest. He looks you in the face and he doesn't blink. Very kind, actually, but he keeps asking questions and they are good questions and it makes you realize your own deficiencies and that can be a royal pain in the ass! But in the end you are lucky because it makes you a better filmmaker; like all great artists he makes others rise to the occasion, push past boundaries.

Every script has got dirty little secrets meaning every script has parts in it that are not perfectly thought out; they're glossed over or ignored because everyone just wants to go make a movie! and any structural problems or character problems can get forgotten for expediency. But guess who's face is gonna be up on the screen for the next two hundred years or longer? The actor. Harvey Keitel's been doing this long enough to know what a legacy is, and each part he does he wants to be part of a body of work that is well-crafted, well-respected and timeless. He respects acting for the art form it is and he expects everyone else involved to hold themselves to a high standard. Was painting the Sistine Chapel easy? Was building the Taj Mahal a cake walk? You got Harvey Keitel show up on your set you think he's gonna let you throw some paint on a wall and send it to the Met? He's sweet as can be. He and his wife were very kind to me and there was one night in his hotel room where he told me all sorts of stories about TAXI DRIVER: talk about being in a dream-world! That was cool. I respect him to no end for a variety of reasons, and hope he will do this other film I have in the works. Harvey Keitel is one of the greats and nobody forget that ever!!

What's obsessing you now?

Besides looking at pictures of the Ferrari 308 on Ebay? That's the one Thomas Magnum drove. I can't afford it and I pretend that my interest in it is ironic, but that car possesses zero irony no matter what you try to do. It's cheesy and gorgeous and if you give yourself over to it it almost seems reasonable to spend $50,000 for a used car that you would be embarrassed to drive in public. Besides that, the God Particle is really pissing me off. I can't get my head around it and it's really bothering me and I'm sick of Yahoo News trying to describe particle accelerators to me and make it seem like everybody should know what all this stuff is. This is time travel talk, folks! I think. My head is too filled with photographs of the Ferrari 308 and the Magnum PI theme and the vague notion that I should learn how to make wine. Also, in terms of obsession, my wife is very beautiful and if I showed you a picture of her you would think she was a Norse Goddess but straight out of a volcano with no bullshit and maybe she'd breathe lovely fire and please print this because I need all the help I can get.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

You should have asked me how we know each other and then I would say that you wrote an extraordinary book called Pictures of You and I made a movie you like and we talked it all over and now we are all looking forward to the not too distant future when you win a Pulitzer, an Oscar and Maximum Millions all in the same year. But really, your writing is exquisite, Caroline, and you are very kind to include me on your site. Thank you.

Published on April 09, 2013 17:28

Jeanine Cummins talks about The Crooked Branch, why not using an outline can be borderline disastrous, if she can come to dinner (yes, you can), and more

A modern young mother in Queens begins to delve into her family history, which might include a murder during the Irish famine--got you enraptured yet? Jeanine Cummin's book, The Crooked Branch is all about fate, heritage, and how our family past can impact our future. I'm thrilled to have her on the blog. Thank you so much, Jeanine!

For me, every book is a question I wanted to answer. What question did this novel ask of you, and did it answer it in the way you expected? I guess the question I accidentally asked myself was this: is it possible for me to become the mother I want to be? Or is my capacity for parenting (for love, for nurturing, for virtues like patience, resilience, kindness, warmth) predetermined by inheritance? My personal transition into motherhood was rockier than I expected it to be – it took me a while to find my footing as a mother, and to create a modern mama-identity that made me feel whole, rather than subjugating the person I was before those gorgeous babies came along. So all of that got me to wondering about the mothers who came before me – my mom and my grandmothers and their mothers, and so on. I started thinking about the experiences of those past generations – how their particular difficulties influenced their parenting, and how that influence might ripple (directly or indirectly) across the generations and into my lap, and how I might unintentionally sing it or whisper it or scream it into the waiting ears of my daughters.

I love the way the novel turned out – these two divergent story lines, these two fierce and feisty young mothers, many generations apart from the same family, battling their very different personal demons. Ultimately, the contemporary mother is able to draw strength from the mothers who came before her. She is able to forgive them for their (real or imagined) maternal shortcomings. In doing that, she liberates herself from that heavy tradition of self-criticism that mothers so often engage in. She chooses what to inherit and, more importantly, she chooses the parts of her inheritance that she wishes to discard. In that way, she gets to determine what kind of mama she will be.

What's your writing life like? Do you plan things out?

My writing life is slightly disjointed right now. In addition to being a writer, I’m a mother to two very small children, so my creative endeavors have to contort themselves around the shape of my family. I feel very lucky in that regard – I have a super supportive husband, and good part-time childcare, so I devote my child-free hours entirely to my books. Because of all that, I have to be very disciplined in my writing. If left to my own devices, I would probably ride my bike, read, and watch television all day for months on end, and then binge-write a whole book in like six weeks. But tragically, I don’t have that kind of luxury of time.

I wrote my first novel, The Outside Boy, without using an outline, and I found that process to be borderline-disastrous. I ended up doing three major revisions (almost three complete drafts) before the book was complete. So this time, for The Crooked Branch, I spent about six excruciating months writing a painstakingly detailed outline. I hated every minute of writing that outline. It was awful. But when it was finished, the book came flying out of me – I wrote the whole thing in about eight months, and the first draft was clean. It needed very little revision. So now, I am sad to say, that I have become a believer in the power of the outline. And I am even sadder to report that I am now working on the outline for my next book. I find that nachos and doughnuts are crucial to the creative process, during the outline months.

What's obsessing you now? Nachos and doughnuts. Oh okay, you probably were hoping for a more literary and inspired answer than that, huh? Well, I’m afraid my brain is pickled from the recent publication and subsequent sleep-deprived tour for The Crooked Branch, so I haven’t had time to cultivate obsessions with my usual gusto. So instead I’ll just tell you that I heard Maya Angelou talking about her mama on the BBC this morning, and I spontaneously wept in my car. I will be buying her new book pronto.

What kind of research did you do for this book? Well first, in order to research the challenges of 21st century motherhood, I conceived, gestated, and bore two human babies. Okay, in truth, I did that just for fun. But certainly, my trials as a first time mama count as “research” where this book is concerned. The contemporary character, Majella, has a lot of familiar struggles in her early weeks as a parent.

But most of my research for this book centered on Ireland of the 1840s, and the potato famine in particular. I always knew I wanted to write a book about the famine, which in Ireland, is not called “famine,” but rather An Gorta Mor which means “The Great Hunger.” It’s called that because the famine was caused by the failure of only one crop: the potato. Wheat, oats, and livestock were all unaffected by the blight, so English landowners continued to export all of that food from Ireland in great quantities throughout the famine years, all while about two million Irish starved to death. By conservative estimates, Ireland lost at least quarter of her population during those years. To me, the most abhorrent thing about that famine – about all famine in a global economy – is how preventable it was. That was the story I wanted to tell, through Ginny and her family.

What’s the best thing about being a writer?

Access to other writers. I am not of the intelligentsia. I don’t have an MFA. I am regular person from a regular family from a regular suburb. My mom was a nurse and my dad was a sailor. I have always loved stories and words and books, and now I get to live a life that is saturated with them. I get to meet smart, soulful, funny people like you all the time, and talk about books and art, even though I am probably secretly thoroughly unqualified for this life. Please don’t tell anyone.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

If I would like to come over for dinner.

Published on April 09, 2013 17:12

Marcia Riefer Johnston talks about Word Up! How to Build Powerful Sentences and Paragraphs (and Everything You Build From Them), why good grammar and punctuation are her mission in life and so much more

Want to learn to write more powerfully? Um, is Italy in the spring wonderful? Well, Marcia Riefer Johnston has just the book to learn how to do it. What I loved so much about Word Up! is that it's so entertaining, that bettering your prose is almost effortless. I'm thrilled to have Marcia here on the blog. Thank you, Marcia!

Why are good grammar and punctuation your mission in life?

Grammar and punctuation are to me what engines and transmissions are to car lovers: mechanisms behind the magic. Just as a car maker needs to get hundred of parts working under the hood to create an enjoyable ride, a writer needs to get lots of things working behind the words to create an enjoyable read. Grammar and punctuation. Rhetorical devices. Style guidelines. Logic. Structure. Rhythm. Sound. Meanings and connotations. A clear purpose (the answer to why am I writing this?). An understanding of audience (who will read this? what will they want or need or wonder about or respond to?). A sense of readers’ situations (where and how and when will people read this?). Open-mindedness. Persistence.A brilliant novel, billboard, or love letter doesn’t just roll out of someone’s head any more than a Rolls-Royce does.If I have a mission regarding grammar, punctuation, and all the elements of masterful writing, it’s to inspire and help equip writers—how shall I say it?—to tune up their engines (Listen! You can hear a certain hum when all the parts are oiled and working together), to clear out their cars (Toss out those stray apostrophes like so many empty food wrappers), and, then, to invite their readers to hop in for a ride to remember.What I love so much about the book is the easy-to-remember tips and tricks. Are these from your own hard-won experience?Yes and no. No, the tips and tricks in Word Up! don’t belong to me. I haven’t figured out anything new. Aristotle said it all two thousand years ago, and writers have been repeating his wisdom ever since.But in a way, yes. After years of reading and writing (and rewriting and rewriting), I’ve arrived at my own sense of what works and why. I’ve discovered what a difference these tips and tricks make. I wrote the book because I’ve discovered that many writers haven’t yet made the same discoveries.What's the best way for anyone to read this book? Skip around? Start to finish?Skipping around works. The chapters are short and self-contained. You could think of Word Up! as a bathroom book: pick it up, and follow your interests. A few minutes here, a few minutes there. Ideally, as with most bathroom books, you put it down with a smile. Next time you pick it up, you can start anywhere.A straight-through reading works, too, because the three main sections increase in complexity—in “chewiness” as one friend puts it. But the topics aren’t cumulative. You don’t need to read Chapter 1 for Chapter 2 to make sense.Can you talk about some of the rules that really aren't rules at all and why we persist in still following them even when they don't serve us?Many people were taught that it’s wrong to end a sentence with a preposition, wrong to start a sentence with and or but, wrong to use passive voice, wrong to use sentence fragments. Like this.I’m not saying that prepositions belong at the end, or that sentences should start with and, or that passive voice is good, or that fragments rock. Here’s the point: strong writers use discernment in these things.Why do we persist in following these “rules” even when they don’t serve us? The fear of being wrong keeps us from doing many things. Writers who want to grow can start by letting go of that fear.What's obsessing you now and why?Now that Word Up! is finished, I want to get it into the hands of English teachers and others faced with passing on writing skills to the next generation. I didn't write this book as a textbook, but from the beginning I’ve had educators in mind. One professor at Portland State University ordered advance reading copies for his editing class this semester. Several other teachers are looking at it. At the request of one writing-center director, I've created a set of exercises that complement the book. Those exercises are available here: http://howtowriteeverything.com/exercisesTeachers, think handouts. One less thing you have to do.I know how challenging it is to teach writing—and how important. Students who write well, think well. The world can’t have too many capable thinkers.What question didn't I ask that I should have?What was the biggest eye-opener in writing Word Up? The importance of feedback. If I had published this book two years ago when I thought it was ready, I wouldn’t be answering interview questions right now. Lucky for me, my husband encouraged me to send that early manuscript to everyone I could talk into reading it. The thoughtful, wise, honest, generous, insightful feedback I received transformed this effort into something I never could have done alone. Every reader's perspective contributed. Feedback helped me get this book’s engine purring and its chrome gleaming. At least that’s how it feels to me. Thanks to a crew of helpers, this baby’s raring to hit the road.Let's take 'er for a spin.

Published on April 09, 2013 17:02

Meg Pokrass interviews Jackie Davis-Martin about Surviving Susan, bravery in the face of grief and so much more

Thank you, Meg Pokrass for this interview

Jackie Davis-Martin’s stories and essays have appeared in Trillium, Midway, Flashquake, Fastforward, JAAM, 34th Parallel, Sleet.com, Bluestem Magazine and Fractured West, Curly Red Shoe Stories (featured writer). A novella, Extracurricular, was a finalist in the Press 53 Awards. Jackie teaches at City College of San Francisco. Surviving Susan is her first memoir.

Jackie, can you give us a brief synopsis of "Surviving Susan"?

Surviving Susan is explained by its rather long subtitle: A Mother Deals with the Death of Her Daughter and Reflects on Their Relationship. I guess “deal” is the operative word; in the beginning of the book I write about the suddenness of Susan’s death and my literal “dealing” –our traveling to Wilmington, Delaware, from San Francisco, and all the physical things that needed to be attended to there. Then of course the further definition of “deal” has to do with coping with the loss. I tried to intersperse my bouts of finding Things that Helped with scenes and vignettes of our past. I wanted the readers to know something of Susan, too. Ultimately, what I hope that the book does for readers is to provide comfort for those who suffer, to tell them they are not alone, as well as offer insights into one particular mother-daughter relationship which might resound in others. I’ve heard from both mothers and daughters who say, Now I understand something I didn’t before. That’s a focus that I am pleased with. The other outcome that has pleased me is to have strangers say, “I feel I know your daughter.” How long did it take you to write this book?I did a great deal of writing for six months. Then I spent a year shaping that writing into particular chapters and vignettes and another few months having parts reviewed, and editing it. The book spans a year, although it took closer to two to put it together.If you can, please discuss the most challenging aspects of writing something so intensely personal. What was challenging was doing something different with grief. What can be different? Particularly daunting is the fact that famous writers have dealt with the subject. Joan Didion, Isabel Allende, Roger Rosenblatt all talked of a daughter’s loss, but they are well known. Who was I, an ordinary person, to talk about Susan, another ordinary person? I wanted to shape the grief into a personal immediacy that others (also not famous) could identify with. Another challenge was to decide what to include and what I had to let go. My own pain had to keep shifting a bit, or reacting to new events, or to old events in new ways. Susan, too, I wanted to represent over time, so it was a challenge to decide what to tell about her, or how to re-create her. I wanted so much to boast: do you know how many trips we took together? There’s much I left out, but the challenge was in the choices. When people experience tragedy, is the tendency to hide or to talk about things.. What you have done here is so very brave. Has it helped to get it outside of yourself?This is an interesting question. Writing about Susan, about us, did help me get outside the experience. And yet, bizarrely, it brought home the realization: I don’t have her anymore; now I have this [the book]. I have to fight against that “realization” because of course it’s too real. However, mostly writing about my personal experience, and the bad and good things about the way we got along, did help. I felt I made concrete what was surely slipping away entirely. What is next for you? What are you working on now?I’m returning to fiction. My fiction is usually based on events in my own life, but there is much more leeway in fiction; one can bend the event the way one likes it, or invent the truth of an experience that had no truth. For a while I was really interested in short shorts—they’re like writing poems—a trick of observation or circumstance neatly turned. But I want to focus on longer fiction—stories beyond 3,000 words. I’m planning to review some old stories and rewrite them, as well as linking and combining stories. I’m thinking of naming my main character Olive Kitteridge. Just kidding.

Published on April 09, 2013 16:49

April 1, 2013

Meg Wolitzer talks about The Interestings, why you should write the books you want to write rather than the books you think you should write, how talent sustains and so much more

I'm so honored to have one of my literary heroines here, today, Meg Wolitzer. Meg is not only a brilliant writer, she's also one of the most generous people on the planet. Soft-spoken, incredibly smart (and, just so you know, I also deeply admire and like her literary mother, Hilma, too), Meg hasn't just achieved huge success for herself, she fights for it for other writers .

Her new novel, The Interestings gets at the thorny, provocative questions, any artist thinks about. How do they keep it growing, and what happens when it gets stunted? Those are just some of the provocative questions raised in Meg Wolitzer's extraordinary novel, The Interestings. Her other novels include The Uncoupling: The Ten-year Nap, The Position, The Wife, a novel for young readers, The Fingertips of Duncan Dorfman. Her short fiction has appeared in The Best American Short Stories and the Pushcart Prize. She'll be a guest artist in the Princeton Atelier program at Princeton University, along with singer-songwriter Suzzy Roche. I'm so thrilled to have her here. Thank you so, so much, Meg.

The whole issue of fame is always a queasy one. I've heard the argument that "talent will out," that it's not a question of luck or timing, but I'm not so sure I believe that totally. Can you talk about that, please?

I suppose it's true that talent will often out, but "out" has its degrees. You can be known among your group of friends as a stellar artist, for instance, or only among other artists, or else you can have a far bigger, more mainstream following than that. I think luck and timing can really be a big part of the equation. Also, what makes someone's career take off in a major way often has to do with zeitgeist issues. An artist's success can be connected to the ways in which he or she intersects with the cultural moment.

So much of The Interestings is about how talent evolves or sustains. You published the wonderful Sleepwalking while still an undergraduate and you've built a stellar career, and gotten more brilliant with every book. Was there anything in particular (besides talent, of course) that helped you craft such a stellar career and keep growing and evolving? Were there ever moments when you despaired or doubted?

Thank you for those kind words about my work. Many things were helpful along the way, but I would say that chief among them was (and is) a supportive mother (more about her a little later) and a wonderful pack of writer friends. My friends and I have always helped one another make certain hard craft decisions in manuscripts, and we've provided publishing advice too, and dark-of-night insecurity-reduction services. Because writing is solitary, it's easy to second-guess oneself, and, left to one's own devices, to feel crushingly bad about a small, perceived slight or a large, public one. Good friends help you take the long view.

As for desires for fame and attention, they are certainly often at their strongest when you're young. They seem so important then, and you're often taking your own pulse based on what others think of you, which is generally an unhealthy way to live. My first editor always said, "Writing isn't a horse race." And this is really good advice to try and remember.

I doubt myself with real frequency, of course, though by the time I hand a book lately, I tend to feel more and more comfortable with my writing decisions.

The envy and despair your characters feel as they watch others grab the prizes of success they are dreaming for felt so real and palpable. Can you talk about how our desires for fame/acclaim/attention change as we age?

Issues of success and attention don't matter in the same way to me that they used to when I was in my twenties and had dreams about what a writing life would entail. Of course I want people to read my novels, and I hope to continue earning a living as a writer, but I see it differently now. First of all, book culture is really changed from when I first started publishing in the 1980s. Back then, people would gather and talk excitedly about, say, an Ann Beattie story in "The New Yorker." You felt that the kind of fiction you liked was a real part of the culture. And now you know that for the most part, fiction is read by a very narrow slice of society. So it's incredibly great when something wonderful breaks through without an obvious hook or reason. But it's not the norm. Most of the writers I know who used to care more about getting attention now seem to focus on finding uninterrupted time to work. Also, they may care less about being well-known and more about having money security--though those two aren't unconnected. But money security frees you up from money anxiety, which is a real writing killer.

I wanted to ask about your incredible essay in the NYT, On The Rules for LIterary Fiction for Men and Women, particularly the odious term "women's fiction" which always, to me, seems to damn a book before it is even out of the gate. What do you think readers and writers can do to start changing these rules, besides talking about them?

You can certainly have a look at your book jacket before it's final and see whether you feel it accurately represents the book and who you are as a writer. You can see that your agent and publisher are sending your books to the people you wish would read them. You can become involved with the organization VIDA, which compiles important gender-breakdown statistics about the publishing industry. And you can, of course, write the books you want to write, not the ones you think you should write.

What's your writing life like? Do you have rituals you need? Do you map things out or do you tend to let the characters lead you?

I work all the time. It's not a fixed routine, but it tends to be pretty constant. I guess I'm sharpest in the early part of the day, and I get dull as the light drain. I love to work, I love to be deep in a book; this is the happiest time I can imagine. I work at home, or in coffee shops, or at The New York Society Library. I don't have rituals, exactly, though I do drink copious amounts of Ito-En green white tea (iced) all day when I'm working, and I even have it delivered so I don't run out.

As for the novels, I usually start with an idea, and the characters seem to fall into line fairly soon afterward. "The Interestings" was a big "character" novel for me, but I never lost sight of the fact that I wanted to write about what happens to talent over time. I tend to let myself write freely for about eighty pages, and then I start to look back at what I've done and see if it's any good or if it needs to be put out of its misery.

Your mother, Hilma Wolitzer, is also an acclaimed writer. Did you know, like your characters, early on, that you were going to follow in her career footsteps? What was that whole experience like?

In addition to my friends, she is an enormous positive influence in my writing life. She was always supportive of my work from the start. Plus, she's so talented, and I loved having a talented mother when I was growing up. I wanted to be a writer from the time I was very young, and through her I saw a writer's life in action, up close. It's been a great gift, seeing how hard it can be, and how rewarding.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Oh, I'm always obsessed with the next thing: how to nail it down and love it and stick with it. It's really hard to switch from one book to another. I guess all novelists are serial monogamists (did I read that line somewhere? Maybe, maybe not...), and this can be difficult.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

I can't think of any. You are very thorough and thoughtful, which is no surprise, since your fiction is too.

Published on April 01, 2013 05:22

March 31, 2013

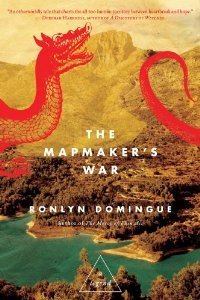

Ronlyn Domingue talks about The Mapmaker's War, the quest for peace, and so much more

I'm so honored to have Ronlyn Domingue here today! She's the author of The Mapmaker's War (Atria Books, 2013). Set in an ancient time in a faraway land, The Mapmaker’s War accounts the life of an exiled mapmaker who must come to terms with the home and children she was forced to leave behind. In this tale, her autobiography, she reveals her pain and joy, and ultimately her transformation, in her own voice. Her prior novel, The Mercy of Thin Air, was published in ten languages. Her writing has appeared in The Beautiful Anthology (TNB Books), New England Review, Clackamas Literary Review, New Delta Review, The Independent (UK), and Shambhala Sun, as well as on mindful.org, The Nervous Breakdown, and Salon.com. Born and raised in the Deep South, she lives there still with her partner, Todd Bourque, and their cats. Connect with her at www.ronlyndomingue.com, Facebook, and Twitter.

Ronlyn's debut novel, The Mercy of Thin Air, was critically acclaimed and published in ten languages. In 2005, it was a Borders Original Voices Award finalist and a RedBook Magazine RedBook Club selection. More recently, in 2010, the novel was a Costco Pennie's Pick. About this book, bestselling author Jodi Picoult wrote, "This is that rarest of first novels--a truly original voice, and a truly original story," Library Journal's starred review stated, "This is a novel that gets under ones skin," and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer called it,"[E]ntrancing and ethereal."

Thanks so much, Ronlyn, for being here!

The Mapmaker’s War takes place in what feels like an ancient period of history. Aoife is out of step with her time, but ahead of it, too. One reason she becomes a mapmaker is to define her life in some way. She’s aware women are meant to be only wives and mothers, and she doesn’t have much interest in either role, especially when she’s young. How do you perceive her struggle with these expectations?

It’s not that she’s opposed to marriage or motherhood. It’s a matter of choice. She writes, “You had no inclination to become what every woman you knew became. A wife, mother, domestic. You didn’t begrudge them their roles if they were freely chosen. Yet who can choose freely when the options are few?” She wants the opportunity to direct her own life and use the capabilities she has. She struggles against the coercion of custom and tradition, the limitations which usually don’t take into account an individual’s potential beyond gender. But readers will see her evolve with her circumstances. Aoife isn’t quite the same woman as Wyl’s wife and mother to his children as she is as Leit’s spouse and mother of their daughter.

There’s a major theme in the novel about the concept of choice, individual and collective. Why is that so significant?

As Aoife’s story emerged and I reflected on the details of her life, I kept thinking about a book I read, Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century by Jonathan Glover. It was a difficult read because it’s about war and genocide, an exploration of man’s inhumanity to man, but Glover includes examples of soldiers and civilians who didn’t give in to violence and cruelty. Most of the book is a complete horror, but when I finished, I had a clear, distinct thought: We choose the evil we do to each other. All of it—from the level of a family to the level of nations. Of course, the reverse is also true. Aoife explores the interrelationship among individual, group, and collective choices—and the power these have to cause suffering and strife as well as peace and contentment.

For me, every book is a question I wanted to answer. What question did this novel ask of you, and did it answer it in the way you expected?

I had to sit with your question for a while. What I realized is that I didn’t know what the question was until I had the answer, but I’m not sure I can so cleanly name the question itself. It has to do with finding peace within one’s self and within a community. In The Mapmaker’s War, Aoife grows up a typical kingdom with the hierarchies we’re all familiar with from stories we’ve been told and the history we all know. But when Aoife crosses the river border of her kingdom, she visits a hidden community of people who call themselves The Guardians. I’ll let readers discover whom they guard, but I will say their culture is based on compassion, equality, and non-violence. In time, she learns why this is so and how they actively, consciously, keep this balance.

As a writer, I found I was challenged to be conscious, too. Personally, I believe our species and every being on this planet are in tremendous peril, much of which we’ve brought upon ourselves. Dystopian and post-apocalyptic stories have a crucial purpose—they allow people to experience, but contain, their feelings of terror and confusion and even rage. However, these stories also fuel bleak narratives of our collective future—a future that in fact isn’t fixed. I discovered I wanted to write from a place of hope, even though I struggled to find it. I realized part of this novel’s power was its offer of an alternative. Aoife’s quest for peace is incredibly human—messy and complicated—but the rewards are possible. She proved that to me. I needed to know, and I imagine I’m not alone in this.

What's your writing life like? Do you plan things out?

Once a project takes root, I spend months and years in what I call my research and incubation phase. This is a period when I keep a giant notebook of what streams through—images, bits of dialogue, fragments of an event in a character’s life, random linkages—and notes on everything I read which somehow has a relationship to what I’m working on. In time, the plot reveals itself, sorts itself out, and I’m able to sketch out the entire arc, beginning to end. So I guess, yes, I plan things out. I already know “what” happens, and I’m often writing to discover “how” those events unfold and connect.

When the writing finally starts, I work full days, six to ten hours a day, usually four or five days a week, but it’s not unusual for me to work on weekends. When the energy runs out, I’ll take a break from the writing and/or revising, sometimes to do more research and thinking, sometimes because I’m exhausted.

I wrote my first novel, The Mercy of Thin Air, on a computer, but almost every word of The Mapmaker’s War was written by hand. I typed up the handwritten manuscript in the break periods.

What's obsessing you now?

I wish I could say it was the revisions of my forthcoming novel or a new project, but it’s not. I’m rallying for The Mapmaker’s War in whatever ways I can conjure. Many of your readers are no doubt aware of the dispute between Barnes & Noble and Simon & Schuster, which has affected dozens of S&S authors who’ve had spring book releases. It’s a tough situation for everyone—B&N, S&S, and the authors. We’re all losing something in this. Ultimately, I have a responsibility to my little beastie to give it a fighting chance. I spent five years on this novel—it pushed me to my limits as a writer and human being—and I believe the story’s message of peace and hope is one this world desperately needs right now.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

So, what’s next for you?

Why, thank you for asking. The Chronicle of Secret Riven will be out in 2014, the epic sequel which takes place 1,000 years after The Mapmaker’s War. In Mapmaker’s, Aoife is told a prophecy about children who will be born in a distant future and a great event that will take place in the land from which Aoife was exiled. Secret Riven, the daughter of a translator and an historian, is one of those children. From an arcane manuscript, Secret learns of her connection to Aoife, and in time, she discovers her role in these mysterious events. I’ll say for the record it involves a plague… (For a hint about the aforementioned manuscript, readers might take a close look at the translator’s note at the start of The Mapmaker’s War.)

Published on March 31, 2013 09:52