Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 74

March 4, 2014

Therese Walsh, author of THE MOON SISTERS talks about the subconscious, muddling towards characters, and so much more

I'm honored to host Therese Walsh, author of the wonderful new novel, The Moon Sisters. Thank you, Therese!

When I’m ready to start a new story, I sit with ideas but not crystal clear ones. Rather, these ideas are like partially formed apparitions; they blink and sway and leave me feeling both unsure about my vision and entranced by it.

When I first sat to write “The Moon Sisters,” I had a fairly good idea about the book’s themes and who one of the sisters would be—a dreamy synesthete named Olivia Moon, who could see music and smell her mother on the sun and knew the taste of hope. Her sister, Jazz, was much less revealing, which made things interesting when she claimed the first chapter for her own. She was angry, this sister—bitter and put upon. She didn’t want to cooperate with me any more than she wanted to cooperate with Olivia, who had plans to track down a legendary will-o’-the-wisp light—a different sort of partially formed apparition that blinks and sways and lures with false promises. Olivia wanted to find one of these wisps because it was her mother’s dream to see one, and her mother had died without this wish fulfilled. Though Olivia believed that seeing a light would help in some significant way, I couldn’t pinpoint the why of that, exactly; and every time I tried to saddle Olivia with a simple reason, like a desire to lay her mother’s spirit to rest, it rang hollow.

Whatever Olivia’s fuzzy logic, Jazz was not interested in the trip. She let me know, almost immediately, that she had other priorities, like starting her new job at a funeral home—the same funeral home her mother’s body had been laid out in just a few months earlier. She wanted to work there, but she wouldn’t tell me why. Fascination with death? Obvious. But why?

Each chapter of The Moon Sisters begins with some form of reflection from either Olivia or Jazz. Sometimes these reflections are a single memory, sometimes they're puzzle-piece realizations about how life up to that point created the person they had become. I fell in love with these segments, and would look forward to writing them and learning more about the girls and their troubled mother, Beth, as the story progressed.

And eventually—eventually—there it was, toward the end of my draft. Illumination. When I realized why Jazz wanted to work in a funeral home, I cried. When I realized why Olivia wanted so desperately to connect with a will-o’-the-wisp light, I cried again.

If you’re a writer, and you’re one who knows all that’s needed about a canvas of characters before you begin writing, then I applaud you. I am not like you, though. I have to muddle through until my characters trust me—or until my subconscious bubbles to the surface. I have to write and write to learn why because it does not come any other way, and never easily. And perhaps I’m a touch masochistic, but I think I like this blink-sway process. As the characters come to trust me with their issues, I come to trust myself with them as well.

Published on March 04, 2014 07:20

February 23, 2014

Censorship is never a good idea: Rebecca Kanner talks about Sinners and the Sea and the Christian readers who boycott it

I was rambling around on FB when I happened to find a conversation from the author Rebecca Kanner about how her novel Sinners and The Sea, which focuses on Noah's wife, was the target of some censorship. A Christian reader was so incensed by the book that she had her local Christian bookstore pull it from the shelves. There was a heated and lively dialogue going on about this on Facebook, and I decided to invite Rebecca here to talk about it. Thank you, Rebecca!

So when you wrote your novel, did you anticipate any of this backlash with Christian readers?

As a girl I attended a small Jewish school where we were free to discuss and even disagree with religious writings. We treated the bible as an open text, a learning tool that allows for multiple interpretations. (I’ve always loved the saying, “Two Jews, three opinions!”)

In Sinners and the Sea I presented one explanation for why Noah’s wife wasn’t named in the bible. I didn’t think everyone would agree with this midrashic explanation, but I didn’t foresee the violent reactions that I’ve gotten from certain Christians. There seems to be a sense of ownership of the bible, even the Old Testament, among fundamentalist Christians. I don’t understand the urge to burn or ban a book, but clearly some people are threatened merely by my novel’s existence, and they want to make sure other people aren’t exposed to it. I imagine sometimes this is out of concern for the other people who they think might be harmed by the book, and sometimes they’re just trying to punish me. I feel that discussing a biblical text, and even arguing with it, is the greatest way to honor it.

Tell us about your novel and what thou intended this story to do. It's been called incredibly cinematic, moving, and you've brought Noah's wife to life on the page. Which brings us to the question: why must a book be written with a Christian sensibility? Isn't the job of fiction to enlarge our world? Would only holocaust survivors be allowed to write about the holocaust?

Several years ago I realized I didn’t remember anything about Noah’s wife. I found this odd because bible study was such a large part of my early education. I went back to Genesis and discovered that she wasn’t named. She was just mentioned in passing five times as “Noah’s wife.” When I saw this, I understood why I couldn’t remember her. Because she didn’t have a name it would have been hard for us to talk about her. It also made it more difficult for me to think about her. I was hoping that by naming her I would bring her into my consciousness and also give us a way to talk about her.

Identity naturally became a theme in the novel. I dismissed the possibility that I found least interesting—that Noah’s wife had a name but she was so unimportant it wasn’t mentioned. When my novel begins she actually doesn’t have a name. She is only able to be identified by her relationships to other people—wife, mother. There is a point in the novel where she asks Noah for a name, and he tells her he’s already given her one, “wife.” Later, when they are on the ark and she considers the possibility that Noah and her sons might die, she wonders, if they die, who will I be?

I came to this question and the other questions I raise in the novel with a Jewish sensibility, one of enquiry and exploration. The narrator wrestles with questions of whether G-d is watching over her or not, and whether this G-d is benevolent or wrathful. Some Christian fundamentalists are upset by these questions.

I naively assumed most people would agree that the most interesting way to study any topic is to get different perspectives. I didn’t expect to hear comments like this one from a post about the criticism my book has received, “… as a Christian, I am not interested in a secular or non-biblical version of a Biblical story and other reviewers seem to feel the same way.” In further explaining to me why my book shouldn’t be in Christian bookstores, she emailed me to say, “The NT indicates that a person is blind until saved through Christ and that the Word does not begin to make perfect sense until this conversion has been made.”

How are you handling this maelstrom? There's a huge discussion about this going on at FB right now, and I see the strong support you have, but do you think there is ever a way of dealing with this?

I allow myself to get worked up or be in a funk for a designated period of time, (usually the amount of time it takes to ingest a couple of bowls of ice cream), then I try to do something productive. I want to engage in discussion with people of differing viewpoints, but I also have to weigh that desire against what I might be exposed to if I open myself up to further hostility. Right now I’m contemplating a response to a woman who burned my book and wrote to me that she had it removed from her bookstore because it “comes straight from the pit of hell.” It’s hard for me to pass up the opportunity to try to reach someone, and I’m curious about what this woman might say if I send her a kind email thanking her for reading my book and explaining myself. But there’s also the very real possibility that she is unreachable and will continue to harass me if she knows I’m reading her emails. My sense is that the fundamentalist Christians who don’t like my book are angry because I tried to engage readers in a discussion about faith in my novel, and these fundamentalists are going to be just as resistant to a discussion with me via email or message board.

The support of readers and friends has been invaluable. They remind me to keep jumping for joy that I have a book in the world, regardless of how angry some people are that I wrote it.

Published on February 23, 2014 15:20

Anna Hope talks about her fantastic debut, Wake, how being an actor might help her writing, the difference between the UK and the USA, her obsession with extreme weather, and so much more

Anna Hope's astonishing debut, Wake, takes place over just five days, where three distinct women grapple with the ramifications of World War I, and how it impacts both them and the men they love. I'm thrilled to have Anna here. Thank you so much, Anna.

So, Wake is your debut, and what an astonishing entry into the publishing world it is. Can you talk about your road to publication?

Ah, thanks so much! My road to publication was not all smooth by any means. I wrote the first draft fairly quickly, in about six months, but then redrafted many, many times before the book was ready to go out to publishers. It was a real struggle to balance all of the different elements of the book. Once it was sent out however, the process was swift, and exciting; in the UK seven publishers entered an auction for the rights and the rights were pre-empted by Random House in the US.

1920 London is an indelible character in WAKE--and so really, is World War I. What was the research like? Did you research before you wrote or during or both? And when did you know it was time to stop--(I imagine there are whole libraries devoted to WWI!)

I’m so glad that London emerges as a character in the book for you; it certainly did for me as I was writing. I was fascinated by what I read about London in 1920 – this empire brought to its knees and crippled by grief. Returning soldiers (the lucky ones) coming home to mass unemployment and severe economic depression. Ex-servicemen homeless and begging on street corners, or selling cheap goods door to door like my character Rowan Hind. And then the tension between the sexes too – the women who had entered the workplace in their millions to take over men’s jobs, only to be pushed back into the home when the war was finished. It seemed such a turbulent, fertile period to focus on.

I read for a year before starting to write, and then I read continually for the two years it took me to finish the book. I became a total geek in the process! It was very difficult to know when to stop, partly because I loved the process so much. I often wished I’d studied history at University and this gave me the chance to indulge my passion for the past.

You've brought to life three astonishing women: Hettie, Ada and Evelyn, all desperate for some sort of closure. Did you always know that you would be writing about multiple characters?

Thank you again, and yes, I did. Firstly I always knew I wanted to write about women as I was very aware that all the known tropes of the war: the trenches, the mud, the barbed wire, were all from the male experience. It felt a though there was an untold story there. I also wanted to write about women from different classes, so that I could explore the breadth of grief and experience there must have been across British society. But I wanted to broaden my canvas even further and include small vignettes of anonymous characters who accompany the body of the Unknown Warrior on its journey home. In this I was very inspired by Colum McCann’s New York novel ‘Let the Great World Spin.” In that book he takes one event, in his case Philip Petit’s tightrope walk between the twin towers in 1974, and explores multiple characters reactions to it. In doing so he brings 70s New York vividly to life. Writing those extra vignettes was liberating for me – I could conjure a myriad of characters to flesh out my narrative and add extra scope to my story. (I could also get more of my research into the book!)

What was your process writing Wake? Did you outline, or did the book grow organically? Do you have rituals? Was there ever a moment when you thought that you were stuck in the mire and you couldn't get out? And what surprised you about the writing?

I knew from the start that I wanted the book to take place over the five days from exhumation to burial of the body of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey in London, but beyond that I didn’t plan at all! Sometimes I wished I had - I wrote organically, and it was a real struggle to balance each characters backstory with the events of those five days; to make enough happen to build a compelling narrative, without things seeming gratuitous.

I got stuck very many times. The redrafting process went on and on. Many long dark nights of the soul! (But then, I can’t imagine what writer doesn’t have these – a novel is such a complex undertaking, just when you think you have got one element sorted, another problem pops up and you have to attend to that.) I have no real rituals when I write, other than writing first thing, before any of the demands of the day interfere. That’s when I get the best of my writing done. If I answer emails or check my Twitter feed first thing then my concentration is fractured before I’ve even begun.

Critics have praised your astonishing ability to get at the emotional landscape of your characters. Can you talk about how you do this alchemy?

That’s extremely lovely to hear. I’ve been an actor for the past twelve years and I suppose my acting background helps with this. In acting training we are taught techniques to immerse ourselves into the physical, imaginative and emotional landscape of our characters. If I’m stuck in my writing then I’ll often return to these – starting with the senses – what can this person see, hear, smell, taste and see? How do they process this information? What is their pace? Is it fast or slow? These sorts of questions are just as helpful to a writer as they are to an actor, they can really help to create rounded, multidimensional characters.

What's obsessing you now and why?

At the moment I’m thinking a lot about the heatwave of 1911 . I’m writing a novel set in an asylum in 1911 during a summer in which the temperature didn’t drop below 90 for the best part of four months. We are having some extreme weather here in the UK – lots of storms and floods – and I just got back from Canada and NYC where there is extreme weather too. So I’d say I’m obsessed by extreme weather, and what it does to us, inside and out.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Good question! I suppose I’m interested in the book’s reception in the US. In the UK and in Canada there’s such a strong relationship to WW1 – in the UK we keep returning to it over and over again. It’s like a scab that we can’t let heal. I think it marks the point at which an empire had to come to realize it was no longer the most potent force on the world stage, and that it had sent close to a million of its young men to their deaths trying to prove that it was. I don’t think Britain can quite forgive itself for that. In the US the cultural narrative of WW1 is very different of course. It will be really interesting to hear US readers’ reactions to the book.

Published on February 23, 2014 13:31

Christian Jungersen talks about You Disappear, brain trauma, the uneasy question of moral responsibility and so much more

What happens when the person you love the most changes because of a brain injury? You Disappear by Christian Jungersen explores just that. Fascinating, and gorgeously written, it's a provocative novel about neurology, compassion, responsibility and so much more. It's truly one of those novels that makes you see and feel the world differently.

Jungersen is also the author of Undergrowth, which won the Best First Novel award in Denmark, and The Exception, which was on the Danish bestseller list for 18 months, won two Danish awards and was shortlisted for major prizes in the United Kingdom, France and Sweden. You Disappear, already a bestseller, recently won the 2012 Laesernes Bogpris, a literary prize decided by thousands of Danish library users.

I'm honored to host Christian here. Thank you so very much, Christian.

You Disappear explores how a brain injury can transform a person you thought you knew into a stranger. How did you research this? What surprised you in the research?

I got the idea for the book because I have an old school friend who’s now a psychiatrist. Whenever we would meet, I would hear stories from her work, and it struck me that her way of looking at people was very different from what I’m used to seeing in fiction. The kind of knowledge she has simply doesn’t inform fictional descriptions of people. Besides of course writing a page-turner readers would find relevant and thought provoking, I wanted to write a novel that tried to modernize the way we conceive of people in literature.

As part of my research, I got to know a variety of brain-damaged people and their families. I worked on this novel for almost five years, and several of these family members became my friends. I’ve grown quite close to some of them, and they’ve shared private details about living with someone who suffers from brain damage, details that I don’t think they’ve even shared with their best friends.In the course of five years, this neurological world became my world. I traveled around hospitals and visited one expert after the other. The novel also features a support group for family members of people with brain damage. I got to know one such group, and I learned what an important role it can play in the lives of affected spouses in particular.

I also want to hear about the sense Mia has that many people, and not just those who are noticeably brain damaged, are not who we think they are. Can you talk about this, please?

The novel revolves around Frederik, who undergoes radical changes because of a brain tumor. But the book’s actually more about his wife, Mia, who changes a great deal too. She’s changed by the difficult challenges that someone always encounters when a person they love becomes seriously ill. And she’s also changed by all she feels compelled to learn about the brain in the course of the book.She starts to look at other people with a neurological knowledge that she didn’t have when the book began. In some ways, it makes her more understanding and compassionate toward others. In other ways, it makes her more egotistical and less respectful. And we follow her as she changes from chapter to chapter.

Sure, she probably becomes a little paranoid toward the end of the book. She sees brain damage wherever she looks, and since the plot unfolds through her eyes, readers may well begin to see brain damage everywhere around them too.

I’ve thought half-jokingly that I might be able to measure the book’s success by how many family doctors start hating me because they’re being pestered by women who now think that their husbands may be genuinely sick in the head.

What do you feel our moral responsibility is? And in what context do you feel that someone whose brain is altered is morally responsible for his or her actions?

Oh, moral responsibility. That’s the question of free will. The world’s most intelligent thinkers have debated it for thousands of years. I have my own take on whether we have free will or not, but I actually prefer not to tell you what my position is. Let me explain.

Regardless of what I might say, it would necessarily be a simplification of the book’s world. Writing a novel is a huge job. You should only undertake it if you can get some substantial pleasure out of it that compensates for all the toil. One thing that gives me great pleasure is the potential that I have as an author to express something that just can’t be expressed in any other form. And one of the ways an author can do this is to create a world in which diverse viewpoints interact and collide with one other. My own little opinion would seem dull and uninteresting in contrast to the totality of all the different approaches to the topic found in the novel. I’m delighted when people tell me that one of my novels seems more intelligent than I am. Then my efforts have succeeded, and I’ve created a complexity and richness that is greater than what you would experience if you met me. So the book’s answer to your question is more nuanced and authentic than anything I could ever say in conversation.

What I loved most about You Disappear was the encroaching sense of dread in the book, the feeling that in a way, we've entered a funhouse world.

That’s really great to hear. It is an entirely different world. And yet I checked everything I wrote with neuropsychologists, neurologists, and psychiatrists. It’s a strange and scary world – and one that is 100% based on fact.

What's your writing life like? Do you have rituals?

Anything that works is permitted. I have a girlfriend who’s studied comp lit. She understands what’s entailed in writing a novel, so she gives me lots of room to indulge myself in the writing process. If I get an idea at 3 in the morning, then I can get up and write as long as I wish, and sleep instead the next day. My writing governs a great deal of my life – and so it comes to govern much of hers too. I’m just grateful that she’s so accepting of what it demands.

I love taking long walks with a pad of paper to write on. I also like lying down and dozing, getting ideas in a state of half dreaming. Sometimes, what’s called for is long hours of grinding away in front of the computer. Other times I might be struck by an idea while I’m out eating with friends. Then I’ll pretend that I have to go to the bathroom during dinner, while in reality I sit out there and write away on the notepad I always have with me. Anything’s permitted.

What's obsessing you now, and why?

I'm obsessing over my next novel. I have loads of ideas in my computer, but I don’t know yet which of them I should choose. Perhaps I’ll combine five of them into a single novel; perhaps I’ll twist one of them in some way that intrigues me. Or someday, an idea might hit that I’ll just know I can’t run away from.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

You might have asked if there were anything I’d like to know about you. And then over lunch, we could have discussed the terrors and great joys of the writing life.

Published on February 23, 2014 13:20

Its or It's? I go ahead and test drive Grammarly

My own grammar-checker just happens to be my husband, who's an editor. But I saw advertisements for a new grammar checker called Grammerly and I thought I'd take it for a test spin, as well as interview the folks responsible for it, or actually just one, Nikolaus Baron. So is Grammarly worth it? I think it actually is. It doesn't take into account creative writing, but if you have an issue with lay and lie, or its and it's, it's certainly helpful. And thank you, Nikolaus, for talking to me.

And don't take my word for it. Test drive it yourself, right here:

So, what made you create Grammarly? How is it different from other grammar programs? And what has been the response to it?

Grammar rules can be confusing to many people and are constantly evolving. Grammarly was created to provide an easy way for students, professionals, job seekers, and English language learners to become better, more accurate English language writers and help them learn and understand the rules of grammar. Grammarly utilizes sophisticated algorithms and powerful cloud-based computers to identify and correct English spelling and grammar mistakes. Grammarly’s technology catches significantly more errors than competitors, while also offering unique features such as writing enhancement and citation suggestions. Grammarly can be accessed 24x7 from any computer via the Internet.Grammarly has more than 3 million registered users, and usage is doubling every year. It is also trusted by more than 250 educational and corporate clients. Moreover, Grammarly currently has more than ONE MILLION enthusiastic and engaged fans talking about grammar on its Facebook fan page.Does Grammarly still work with someone writing creatively? For example, novels often break grammatical rules, using sentence fragments, etc. Grammarly’s grammar checker is built around a powerful and ever-evolving algorithm, which is not designed to replace teachers or proofreaders but to provide students, professionals and advanced language learners with an automated, cost-effective, accurate and always available online tool to help improve their written English skills.

Grammarly isn't intended for professional writers to achieve the next level of language mastery, or to judge artistic prose. Grammarly is meant to proofread mainstream text like student papers, cover letters, and proposals." Masterful and creative English writing sometimes triggers our alerts. There are limits to what modern technology can accomplish.

What mistakes do writers most often make and how can Grammarly help them? Here's a great blog post from the Grammarly team on the top writing mistakes that writers often make: http://www.grammarly.com/blog/2013/writing-great-american-novel-top-three-mistakes-youll-make/

What's up next for Grammarly and why?One of the most innovative products that Grammarly has introduced to market is the Grammarly® Plug-in for Microsoft® Office Software. This integrates Grammarly’s core grammar checking engine with native editing interfaces such as Microsoft® Word™ and Outlook®. As a result, writers may now incorporate Grammarly’s industry-leading spell, grammar and plagiarism checking technology into their Microsoft Office suite. Grammarly also has plug ins for Chrome and Firefox.

We’re looking forward to integrating in the future other Web-based platforms and applications to help writers perfect their English, wherever they happen to be writing.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?We'd love to share some of our most meaningful company-wide accomplishments at Grammarly:

Grammarly makes a meaningful impact in users’ lives; students get better grades, professionals accelerate their career progress, and language learners improve their written English.

Grammarly saves users time in the writing process.Grammarly is licensed by leading colleges and universities.Grammarly was bootstrapped by Alex Shevchenko and Max Lytvyn, both English language learners, to 3 million members.

Cheers,

Published on February 23, 2014 13:07

February 13, 2014

Escape from Ultra-Orthodoxy: Leah Vincent's brave, astonishing memoir: Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After My Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood

Some books just grab you by the throat. What would you do if you had been raised to worship only God and the men who ruled your world? Leah Vincent grew up in a Yeshivish community, and when, at sixteen, she dared to exchange letters with a male, she found herself cast out by her family into New York City, where she often by using her sexuality to survive. Brutal and bruising, Cut Me Loose is about how we find our freedom, and what that freedom might cost. I'm honored to host Leah here today.

You are incredibly brave. At 16, after exchanging letters with a male friend, your parents, ultra-Orthodox Jews, put you on a plane and cut off ties. How were you able to hold it together and become a dazzling author? Did you ever imagine that this would be the outcome of your life?

Thank you Caroline. It was a very long journey – and I did a whole lot of falling apart along the way. It took radical hope, and a willingness to pick myself up after I fell down, again and again and again, to get to where I am. When I was going through the worst of it, as a teenager and in my early twenties, it was inconceivable to me that I’d be as happy and blessed as I am now, with a new family, friends and community that support me, and a life busy doing what I love.

What sparked the writing of this book and what surprised you as you were writing it?

I had promised myself, that if I survived, I would write this book. About a year after finishing graduate school, I heard about the suicide of another former ultra-Orthodox Jew and it moved me to fulfill that promise. Hearing about this tragedy reminded me that there were still so many people out there struggling, and that telling my story might help them feel less alone and might help raise awareness about how challenging it can be to leave ultra-Orthodoxy.

I was surprised by how difficult it was to write this story. I thought I could just transcribe my dairies, but it takes a lot more thoughtfulness and self-awareness and technique to effectively convey a personal story to the public.

So much of the memoir is also about how women are taught to find male approval, even in an Orthodox setting, and how that transformed into your trying to find male approval through sex. Can you talk about that please?

Yes, this seeking of male approval was particularly intense in the patriarchal community I was raised in, and once I found myself on my own, the hunger to please the men in my life translated into a very toxic relationship with my sexuality. But even outside ultra-Orthodoxy, many women are groomed to spend an inordinate amount of energy vying for male approval. It’s such a waste of energy and potential. It’s so important to have a strong sense of self permission and not rely exclusively on the approval of people around us. That said, it is natural to want the approval of authority figures, so it’s important to expose our daughters to strong female role models to emulate, so that the hunger for approval is directed towards someone young girls can one day imagine becoming.

How difficult was it to write such a dazzlingly honest book? Did you fear repercussions?

Very difficult. And looking back over the past few weeks, I can say that in some ways talking about it in the public sphere has been even more difficult than the actual writing. Although revisiting some of these memories was painful, writing for a reader felt intimate and safe, but standing tall and sharing my story on the radio or in newspapers has been even more challenging. I am deeply grateful to my friends who have supported me and loved me as I grapple with confronting my ghosts and finding my strength. That said, the whole experience has been an enormously gratifying one and I am so appreciative that I have this opportunity.

I did fear repercussions. Other former ultra-Orthodox Jews who have spoken openly about their lives have faced a fierce backlash and I expected the same. It hasn’t been as bad as I had expected, but I am still vigilant about raising awareness when it happens – I don’t mind the things people say about me – I mind the message that bashing sends to others in the ultra-Orthodox community who are contemplating leaving. Ultra-Orthodox leaders who bash dissenters need to be held accountable.

You've not only transcended your past life, you've created a new one, becoming an activist. What prompted this decision and can you talk about it?

In the past few years the community of former ultra-Orthodox Jews has blossomed, and it’s a fascinating, creative and passionate community. There are many people who are struggling to leave ultra-Orthodoxy for a self-determined life and I believe it’s a moral imperative to support them. I’m involved in Footsteps, the only organization in the United States serving ultra-Orthodox Jews, and a number of other advocacy projects that support these individuals. It’s very exciting to be working with my peers on these fundamental human rights issues.

What's obsessing you now and why?

What’s obsessing me now is the question of truth and women—how hard it is sometimes for women to speak openly about the more painful aspects of their lives, but how much value there is when we do so, and then how much backlash – both inner and outer—that we have to face when we do, and how to support each other so we can live in a world where we don’t have to suffocate our “shadow” sides.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

These are all great questions!I love to talk about memoir in general, to give a context to the story I tell. I learned a lot about memoir as I was writing my book, and since we all tell the stories of our lives to ourselves and the people we know, I think it can be interesting for readers to think about memoir as well. Think about this art of how we construct the narratives of our lives, think about the choices we all have, in who we cast in which roles, where we find the arcs of redemption, where we find the opportunity to mark a milestone, to start a new chapter, how much judgment and analysis we overlay on the past, how much compassion we can have for the characters in our life, and when we should choose to share our deepest stories with the world.

Published on February 13, 2014 17:49

Jessica Handler talks about Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief, being in the moment, writing, and so much more

I wish I were, but alas, I'm no stranger to grief. Grief isn't easy. But sometimes, writing about it, can help heal or at least put the pain into perspective. Jessica Handler has written a compassionate, compelling and deeply helpful book for anyone facing grief and wanting to write about it. She is the author of Invisible Sisters and Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief and Lost. Invisible Sisters was named one of the "Twenty Five Books All Georgians Should Read and was Atlanta Magazine's Best Memoir of 2009. I'm so honored to have her here to talk about the book that Vanity Fair called, "A wise and encouraging guide."

What is so great about Braving the Fire is that it talks about grief from a writer's perspective instead of a more clinical one. Can you talk about that please?

I’m not a clinician, but because I grew up in a situation where doctors, prescriptions, and medical terminology were a part of my family’s life, so I’m conversant in a certain level of “medical speak.” I’m also acutely aware that in clinical environments, there’s an unfortunate tendency to consider a patient or family member as an illness or a diagnosis rather than as a person. That’s sometimes reinforced by the use of clinical language, which can be de-humanizing. Writing about ourselves and the difficult experiences that have changed us requires that we see ourselves and write about ourselves as what we are – as people. For writers, techniques like detail – the sensations surrounding the time you took the dog’s leash down from the peg for his last walk – or character – finding an empathetic element in the person who sold your friend that fatal dose of drugs – brings a story fully to the page. That’s some of how a personal narrative becomes universal.

You write about being "transformed by loss." How are people transformed and what happens if they get stuck in their grief? How can writing help?

Grief, which isn’t only death and dying, but all kinds of loss, changes who you thought you were going to be or how you thought your life would work out. There you were, living your regular life, and this thing happened. Maybe you’re uprooted by war or environmental disaster, maybe your romantic relationship ended badly, perhaps an illness or accident or addiction (which is an illness) has changed your story. That’s what transforms us, against our will. For those of us who want to write about who we were and who we have become, writing is our way of examining how we’ve changed. It’s exactly what you say; that stories are what saves us.

I've long felt that stories are what saves us. Are their stages in writing about grief that lead to healing?

In Braving the Fire, I applied the Elizabeth Kubler Ross “Five Stages” of Grief as a kind of scaffolding for beginning to write about what I sometimes call “the tough stuff.” I don’t subscribe completely to the idea that we all experience grief in a specific, linear, way. I’ve spent plenty of time in Depression, but very little in Denial, for example. Most people, though, are familiar with the “Five Stages” as a concept. I added a sixth stage, “Renewal,” that relates purely to writing. So, in Braving the Fire I write about how that first stage, Denial, can be seen as denying yourself the prerogative to write. I give examples of how denial stopped me, at first, and other memoir writers, and then writing exercises and prompts to overcome that. Anger has to do with character and interrupted life. I loved applying the third stage, “Bargaining” to research techniques and to form. We bargain with our work – and it bargains with us – about what will go into a manuscript and what we’ll leave out, and figuring out the form a piece will take is also a bargaining process. That sixth stage that I made up, “Renewal,” is about learning to recognize yourself as a writer who has built a bridge between who you were before the loss and who you have become in its aftermath.

You talk about how some people burn their journals of grief, and it's funny, although I cannot bear to look at the journals I wrote when someone I loved died, I can't let them go either. Can you talk about that, please?

I don’t know that I can talk about it from my own experience, because the idea of burning my journals is just so antithetical to my own writing! I have several friends who’ve done it, and I speculated in Braving the Fire about why they did it, but in my case, my first book, Invisible Sisters: A Memoir wouldn’t have worked without my journals (speaking of bargaining!)

I’ve kept journals since I was about nine, and I still have them. I read through them when I wrote Invisible Sisters in order to get a sense of who I was as a little girl, teenager, young woman, as my sisters’ lives went on around me (and then as they died.) I didn’t write for months after my sister Sarah died, and that gap in my journal writing was, in a way, a representation of my voice unable to speak. Maybe people can burn or otherwise discard their journals because they don’t want to look back, or find it too hard (it can be very hard!) or they want to make a new start without any reminders.

What's the most important thing you would like readers to take away from your book?

I’d like readers to come away from Braving the Fire feeling confident in writing about the difficult subjects in their lives, and knowing that they’re not alone in their desire to do so.

What's your writing life like?

I like to think that the more I have on my plate, the more productive I am. I try to write about two hours a day, first thing in the morning, which for me is around 7 a.m. If I get those few hours in, I feel settled, and then I can focus on other responsibilities. I teach creative writing at Oglethorpe University here in Atlanta, and I lead writing workshops on line and in person around the country, so there’s preparation and reading that I want to focus on without fretting that I haven’t written. I have a studio in my house, but I find that if I’m writing an essay, I sometimes do that better at a coffee shop. With earplugs. And a soy cappuccino.

What's obsessing you now and why?

There was a category on my elementary-school report cards called “Uses Time Wisely,” and I’ve never forgotten that. I was always proud when I got a check mark in that column, but I have no idea what the standard was. I’m pretty obsessed lately with making sure that I am present in whatever I’m doing, including giving myself time to space out and think and just be. In yoga it’s called witness consciousness. I’ve noticed my attention span is getting kind of fried, so I’m thinking about enforcing a “digital Shabbat” for myself one day a week.

What question did I forget to ask?

In writing this book, I reached out to friends and mentors and people I hadn’t met but I admired their memoirs about loss and trauma. I wanted to talk with them as a writer about how they managed to write so beautifully and clearly about their own difficult subjects, and with permission, included their insights and salient excerpts from their work in Braving the Fire. I talked with about twenty people overall, including Abigail Thomas, Nick Flynn, Natasha Trethewey, Lee Martin, Rebecca McClanahan, and Katharine Weber, because their work mattered so much to me as I learned to write my story. I feel strongly that there’s a community of writers who address this subject, and I wanted my readers to know that community exists.

Published on February 13, 2014 14:51

February 5, 2014

Rachel Joyce talks about Perfect, children forced to become their parents' parents, jumping in to find the story and how she always wants a cup of tea

Perfect, by Rachel Joyce is a perfect book. About a strange accident that changes the lives of the characters, in particular, a young boy, it's also about time, class, and the glue that can hold lives together. Rachel, the author of the critically acclaimed The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, is also the award-winning author of more than 20 plays for BBC Radio 4. I'm honored to have her here. Thank you so much, Rachel.

I always ask, what sparked this novel? Where did the idea come from?

The first nugget of the story came to me about thirteen years ago. My third child had just been born, and I was driving my oldest daughter to school. She was very nervous. My second daughter was cross, the baby was crying, traffic was heavy. I hadn’t slept for days. And I suddenly realised that if I made a mistake, if someone ran into the road, if anything unexpected happened, I didn’t have the energy, or the space, or even the imagination, to deal with it. I was stretched as far as I could go. It was terrifying. I began writing the story as soon as I got home.

Of course – like most things – the story I began with changed over time. But I came back to it as soon as I had finished ‘The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry.’ I think I had to write that story first because I had to learn I could get to the end of a book. I had to work out how to do it. Perfect is – for me – a much more complex and ambitious piece of story telling. It takes two time strands – 1972 and the present – and asks the reader to make the connections.

What I loved so much about Perfect was the sense of weirdness skating under the ordinary. How difficult was to achieve that balance? And were you unnerved in the writing of the book?

I suppose the things that I see and the things that interest me are the very small ordinary details which in fact tell huge truths. We all have different ways of seeing the world and being part of it, and that is mine. I am never un-nerved by the writing of a book, or at least not by the turns it takes. I just try very hard to find what feels like the most truthful way through a story.

The book delves into how children sometimes have to take control of things, and they have to tend their parents, rather than get the tending they so desperately need. Can you talk about that, please?

I think it is a very sad and tough thing when a child feels he or she has to mother or father a parent. But it happens. Byron, the boy at the centre of Perfect, has just reached the point where he is physically bigger than his beautiful and fragile mother. That is such a delicate stage in a child’s growing up. You want your parents to remain bigger than you and suddenly you are looking down on them.

Of course when a child does as Byron does, and tries to become the parent, they make terrible mistakes. They try to fix an adult world but they still have a child’s understanding. And I think it causes them to miss out a crucial part of their development. They jump from boy to middle aged man. There is often a penalty to pay for that. Byron becomes split from himself and it takes the course of the book for him to heal.

What's your writing life like? Do you outline or do you simply follow your muse?

I do both. For me, an outline is all very well but I don’t really find a story until I jump in there. I have to accept that I will make lots of mistakes and some days I will be very fed up with it. Having said that, the structure of a book is so important. As far as I am concerned, there is the story and then there is the question of how you will tell it. I also write the ending very early on. It helps me to know where I’m heading.

I write every day. Until I’ve finished a new story, it is always loitering around on the kitchen table, making a nuisance of itself.

What's obsessing you now and why?

My third book! Oh it is dragging me around by my neck. This is the way it goes. For me a new book is there all the time, trying out sentences in my head, trying out different ways of telling itself. I end up waking at stupid hours in the night when the family is asleep. I end up sitting at the kitchen table and writing in the dark. It is in my head when I drive the children to school or make the tea. There is no getting away from it. And that isn’t always a pleasant thing to go through. I liken it to being at sea. (Not that I am a sailor.) It’s lonely, very lonely, and you hope you are going the right way. You hope you will see land and an end. But you do. In the end you do.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

You could ask me if I would like a cup of tea. (Yes. Always yes.) Or a walk? (I need to get away from my head.) Or you could ask what inspires me? The answer to that would be the landscape where I live. The changing sky. The longing for spring. In England we have spent six months being rained on. It’s not surprising we need stories.

Published on February 05, 2014 09:09

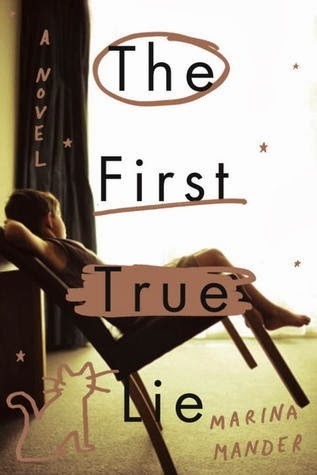

Marina Mander, author of The First True Lies writes about writing, creativity, and so much more

Marina Mander's exceptional novel, The First True Lie is harrowing and poetic, a combination I love.About a young boy who navigates his life after something terrible happens to his mother, the novel also explores the connections between people, and the ways we create narratives so we can survive. I'm honored to have her hear, writing about her creative process. Thank you, Marina.

From Marina Mander, author of THE FIRST TRUE LIE

Everything I write comes from a spark, an intuition, a thought or a fact that hits my imagination for its high emotional potential. They are little seeds that already have a whole story inside, writing is allowing them to grow, caring for them with patience and love. My novel, The First True Lie, for example, was born from a simple but strong idea: even in a big city you can feel totally abandoned.You don’t need to be poor or neglected to experiment the depth of loneliness. It’s a clear feeling that I tried to develop in a creative way to the extreme. My last novel, Nessundorma, was born from a more complex and multifaceted story. I started writing after discovering a terrible reality: that people who are waiting for an organ transplant have a greater chance to get one after major events, because healthy young people can die, drinking and driving or celebrating too much. The contrast between life and death, joy and despair, is already a story in itself, I only had to build it, one brick at a time. Writing is a way to investigate the oxymorons of our lives…

But I’m not a methodical person, the kind a writer that wakes up at the same time to produce a certain number of pages. I can spend a lot of time just thinking about an idea, waiting for the right moment to write it. If the process is ripe, the words are ready to inundate the page, just like a pianist playing on the keyboard. The more precise and accurate work comes later. When the overall plot is fixed, I start revising it over and over again--this is the stage I love most. If I come to the point of edits, it means that the idea has worked well and I can really twist the words around, digging into my personal dictionary to find the most appropriate correspondence between words and emotions. That’s not as rational process as it might appear at first sight, however.I have to concentrate on my deepest feelings, trying to bring back to life forgotten sensations--only then can I properly name them. As I usually say, you don’t need to have survived an airplane crash to describe it, but you must have fallen off your bike when you were a child; you have to be able to re-enhance the fear you once felt and be as honest and faithful to your inner feelings as much as you can. The plot may be influenced by cultural, political, or historical circumstances and beliefs, but the undercurrents of the emotion are universal and could be shared by almost anybody, anywhere. We all have experienced the terror of abandonment once in our lives, never mind why and when: if I can reach the heart of this, I’ll probably reach my readers’ heart as well. Writing is giving style and coherence to elemental forces that we are not always able to connect to. This is the challenge!

Published on February 05, 2014 08:59

The sublime Gina Frangello talks about her devastatingly great novel A Life in Men, how illness defines us, how others save us, and so much more

If you had to choose one person to hang out with over a glass of wine, you'd want to hang with Gina. Funny, smart and warm, Gina's also something of a genius writer. When A Life in Men came through my door, it was one of those books that literally changed my life. About two friends, about illness and what it does to us and to others, about memory and how we choose to live our lives, this extraordinary novel is unlike anything I've read before.

Gina's the Sunday editor for The Rumpus and the fiction editor for The Nervous Breakdown, and is on faculty at UCR-Palm Desert's low residency MFA program in Creative Writing. The longtime Executive Editor of Other Voices magazine and Other Voices Books, she now runs Other Voices Querétaro, an international writing program.

And On February 11, at 7, Brooklyn's fabulous Word Bookstore, I will be interviewing Gina and Rob Roberge. Come see us if you can!

And Gina, as always, thank you. For this, and for everything else.

I always ask, what sparked this book?

It’s strange what a hard question something this basic can be—which I’m sure you well understand. The most direct answer is that the novel was inspired by a college friend of mine, with whom I briefly lived in London in 1989, who had Cystic Fibrosis, as Mary does in the novel, and who was then—and became even more so—an avid traveler despite the very real challenges of her disease. I found her a deeply inspirational person, in a very non-cheesy, anti-Hallmark kind of way: she was bold and funny and irreverent as hell and wild to the point of at times seeming a bit reckless, or at least impulsive. We were close briefly, and I saw her only a couple of times in the next ten years before she died when we were 30. She was at that time living in Jordan among the Bedouin people, while pursuing a degree in cultural anthropology. I had a kind of short-lived sentimental obsession with the idea that I should write her biography, and even wrote her mother (who probably had no idea who I even was) a letter about it. It was sort of a crazy idea. I had never published a book and nonfiction was not my area and in reality I barely knew this woman as an adult…we had lived and traveled together for a few months when we were both very young, and the gulf between 20 and 30 is a wide one, and whoever she had become in that period was not someone I had any claims on. Anyway, that idea quickly dwindled. I went on to write several other books—all fiction—and two of them were published. Then one day I was writing a short story inspired by a place I had lived and worked in London the year after studying abroad, and out of nowhere I gave the main female character, who was actually based…well, on me, cystic fibrosis. My friend who had CF never lived in that house or known the men the other characters were inspired by—she and I were not even in touch at the time. But it became clear to me that the ways she had inspired me were still…at work, I guess. And suddenly A Life in Men was off and running, not attempting to be true or factual to its inspirations but becoming solely a work of fiction.

This novel is so multi-layered and so ambitious--and also so totally harrowing, moving and alive. I’m wondering about your whole writing process, so please spill the beans. Did you map it out ahead of time? How did it morph and change through the writing, and what surprised you about the book? What did you discover that you didn’t know before? And were you scared writing?

I never outline short stories but I do always have an outline for novels by the time I hit a certain stage in the writing—and of course the outline always ends up changing by the very end. Two major changes completely upended this novel during the course of the writing. The first was that initially, the character of Nix, Mary’s best friend, was going to appear only in the first chapter—the Greece chapter—and the entire “truth” of what happens to Nix and how it impacts Mary was all revealed in the first 30 or so pages of the novel. But after initially writing it that way and my former agent even approving that and beginning to shop it, I realized that I needed Nix’s presence threaded more throughout the entire novel, and for Mary’s revelations about what occurred and what their friendship had meant in her life to be more gradual and to serve as echoes for the events of Mary’s own life, as she moved into true adulthood. So I broke that chapter up—expanding and changing it a great deal in the process—and ended up creating kind of a dual narrative where Nix’s story, though much shorter than Mary’s in pages, threads throughout the entire text too. The other major change, which happened around the same time, was that I spent a month in Kenya thanks to Summer Literary Seminars, because Mary Gaitskill (whose work I worship) chose me as the winner of their fiction contest and that got me sent to their Kenya seminar all expenses paid, and then prompted me to travel within Kenya once I was there. I came back from Kenya basically…well, knowing that Mary had been there, and that I had to include that part of her story. The Kenya chapter became the second chapter of the novel, and necessitated, in a radical way, a revision of all of the other chapters. Which, yes, was terrifying. As an editor, I’ve seen that sometimes writers don’t know when to let a project go, to surrender and trust that something is done, so I wondered whether I was in fact fixing something that wasn’t broken and if I would consequently ruin everything. But ultimately I believed so strongly in the new direction that I would not have wanted the previous version published anymore, so I really had no choice.

So much of your novel for me was about the people who save us, in both friendship and love or just in experience; the people we want to save us; and the ways we can try to save ourselves. Would you talk about that, please?

I both love that you asked this question, because there is nothing in the world more interesting to me or that I would more like to talk about, and yet I’m horrified that you asked this question, because it’s a deeply difficult thing for me to try to articulate. I think the most accurate thing I can say on this front is that I have something of an obsession with the ways in which people love and save one another, and how that doesn’t always look the way we are told it should. But that sounds more general than I mean it. Here is what I mean: I think in life, unconditional love and a kind of primal recognition are about the hardest things to find. I believe that most lucky people are able to experience love and a certain level of intimacy, but that even this being true, many people also go through life feeling fundamentally alone and misunderstood, even if they have best friends and siblings and spouses and decent relationships with their parents and whatnot.

It seems to me that many people feel, perhaps without even consciously realizing it, that a certain amount of loneliness is simply the human condition, or that there is a core of ourselves that we would be less loved, less approved of, less embraced if we revealed fully, even to ourselves. Some people, like Yank in the novel, have very dramatic secrets and guilts, or past traumas like what happened to Joshua in South Africa or Nix in Greece, whereas other people simply feel that somehow the “essence” of them is not quite as good as what they are performing for the world, even if they can’t place why this is so and are not explicitly hiding anything concrete and haven’t committed any crimes. There can simply be a great deal of disconnect between the level of intimacy we would like to feel with others versus what we really do feel, even in very close, loving relationships. And we are all told relentlessly in this culture about how no one else can “save” us, and this is…well, frighteningly true on one level. I mean, no one can be saved, or experience true intimacy, if they insist on coming at the world from a place of self-loathing and alienation and victimization and viewing people as fundamentally Other from themselves. No one can be dragged into a state of peace or self-acceptance. And yet, without an intersection with others, saving and loving oneself would be nothing but a lonely business. That intersection of what it is to do this for ourselves juxtaposed with what it is to fully trust, to stop performing what we think the “best version” of ourselves is, to let other people really see and know us—I feel like there is a level of trust or recognition that can happen between people that can almost shock the human system and rewire it, and that fascinates me. I believe that when these connections happen, it gives self-saving a new meaning. I’m not sure this was very comprehensible or articulate, because like most things that mean a great deal, it’s very hard to express cleanly. And yet, it’s really for me what the entire novel is about.

Tell me about the title. It works perfectly and yet it’s so evocative.

The title has a couple of functions, really. On the one hand, Mary’s relationship with Nix, as a kind of absent presence, is so psychologically dominant for her through much of the novel that the title is almost ironic, because the relationship in Mary’s life that impacts her the longest and the most is with another woman. Mary also spends much of the novel pining for and imagining her biological mother. And yet in a sense, because of the dominance these two absent-women have in her psyche, she is not terribly good at letting other, real-life women in, including her adoptive mother, but also other potential female friends over the years. Consequently, she is far more comfortable and unguarded with men, and her life, on the surface, seems entirely shaped by her relationships with the men she encounters, whether familial like Leo and Daniel, or her husband Geoff, or friends like Sandor, or lovers like Joshua and Eli, or those like Yank who straddle a line between many of these things. Mary is a collector of experiences, very volitionally, and in her early years men like Joshua and Eli are almost, for her, like collecting new countries. By the end of the novel, the men of her life serve very different roles and functions than in the beginning. By the end, she has come to both understand Nix more and yet to have outgrown her dependency on that phantom relationship, and to have forged more intense intimacies with men who really know her on a level she and Nix never allowed themselves to be known by one another—for noble reasons, probably, out of a desire to protect one another, yet that kept them as distinct islands regardless.

There is a thread about terrorism that runs through the book, but you touch on many different types of terrors that people live with, as well. The terror of a life not lived well. The terror of losing a friend. The terror of illness. Do you feel that human connection can save us?

I probably said quite enough earlier in terms of my thoughts about the nature of how we save ourselves and each other through connection, but I guess here, in terms of the way we process danger—because, I mean, life is danger, right?—I would add that human connection is all that can save us. Mary’s life is impacted by many terrifying forces, whether it’s the Lockerbie Disaster or the threat from inside her own body, at work in her genetics, in her lungs. But of course, every body on the planet is born to eventually break down and die. Whether we never survive childhood or whether we live to be 90, no one gets out of Life alive. Whether we live through the extremity of genocide or a holocaust or a 9/11 or losing a child, or whether we simply face the more “ordinary” tragedies of caring for our dying parents and losing some of our friends in middle age to cancer or accidents, excruciatingly painful loss is a fundamental part of the human experience. Everyday life includes war waging somewhere and earthquakes and tsunamis, and even the safest and most fortunate life on the planet ends with death and loved ones left behind grieving…I mean, it’s hard to understand, existentially, what it’s all about, and probably there is no answer to that question, there is no ultimate Meaning or Purpose. But the moments that transcend fear or that make loss bearable are all about human connection. A lot of people have experienced moments of such complete love and happiness and connection that they have felt variations on “If the world exploded right now—if the walls fell down—if my heart stopped beating—I would die perfectly happy and I have had enough.” Those moments are almost always inextricably linked to connection and love. If there could be a “why” in terms of why we live and why it matters, I cannot really imagine what else on earth it would be.

The novel also brilliantly captures what it’s like to be young and out in the world and unaware of the dangers, even though they are very, very present for both Nix and Mary. One of the passages that really undid me comes at the end when Mary is reflecting, in the midst of tragedy, on what a lucky life she’s had, and it was at this point, I felt she was truly an adult. Actually, a lot of the characters have this hard-won knowledge at the end, coming at a time where they can’t really use it anymore, but it’s still incredibly valuable to them because it shapes their lives. Can you talk about this, too?

I believe strongly that a great deal of both luck and happiness lies in perception. Take a look at my essay “This Is Happiness” from The Nervous Breakdown. I mean, I want to be clear about this in that I feel very cognizant of the fact that there are a lot of people in the world whose levels of just being dealt a shitty hand are so astronomical that “perception” would be a ridiculous and privileged way to frame it—no one is going to tell someone who, for example, is watching their children waste away with hunger that they should get their ass in gear about “perception.” And yet that said, there is something I have long found deeply objectionable about certain “entitled” aspects of the American consciousness that pushes people—especially those of us who are educated and have enough money to live comfortably—to believe that somehow perfect health and the attainment of all our goals and living to be eighty-five is, like, our birthright or something.

The truth is that illness and struggle are intrinsic parts of life and that no one is entitled to have it easy as some natural order of the universe. In the late 90s I was chronically ill with a pain condition for three years—it was one of the darkest periods of my life, maybe the darkest, really, because when you’re in extreme bodily pain all the time it’s very hard to access other kinds of joy over achievements and relationships. Yet it was also desperately important to me to understand, fully, that this shit just happens. Like that it wasn’t the world somehow singling me out and screwing me over. It’s not a “why me?” situation. It’s not a Somehow-The-World-Would-Be-A-More-Fair-Place-If-This-Happened-To-Someone-Who-Was-Not-Me situation. I’ve always been kind of shocked by that phenomenon, you know, when someone is devoutly religious and then their wife gets in a car crash and dies, and suddenly that person is shaking their fist and saying, “How can God allow these unfair things to happen?” Like they had never heard of the Holocaust or no one else’s wife ever died. If your world view and perspective is contingent on the world having to be “fair” to you amidst the wider chaos of other people’s misfortunes…I mean, it’s a recipe for misery and stagnation. Life is very difficult. Even the easiest of lives is full of challenges.

There is virtually no horrible thing that can possibly happen to you that has not happened to thousands or millions of other people throughout history. Tragedy can be horrifyingly impersonal. It is impossible to make sense of it. And yet life can be blindingly beautiful, too. Almost no one wants it to end. We humans love it—we cherish it.

Perspective matters. Mary is born with a life-shortening illness. Some genuinely awful things also happen to Nix, that are even more violent and disturbing than being terminally ill. It would be very “easy” to see either of these women as victims of a bad fate or unlucky circumstance. And yet to see your own life that way is to guarantee your life being unsatisfying. It is to guarantee that what time you have, however long, will be full of thrashing anguish and unfulfilling and full of feeling cheated and frightened and enraged at what “should” have been yours. It felt incredibly important to me that both Mary and Nix, in their separate ways, would come to a place of being able to choose love and joy over bitterness and victimization. Nix writes in her letters that for her this is not about some Buddhist notion of detachment or emptying herself of desire—she is someone who desires profoundly, as does Mary. They don’t achieve acceptance by distancing themselves from their feelings or their own stories or the scale of their lives, but by the exact opposite, if that makes sense. Both Mary and Nix, separately, ultimately come to a place where they desire joy more than they desire bitterness or self-pity or score-keeping. It turns out to be, for both, very late in their short lives…but I would say that it is not at all too late. I think it’s never too late.

Mary struggles with being chronically ill, hiding it, while trying to gulp down the life she does have. As someone who survived a critical illness for a year, I have to say, you got this so, so exactly right. What was your research for this like? How did you know what you know to put into the book?

I read a lot of books about cystic fibrosis, of course, and a lot of blogs and things like that, but honestly this part of the novel, psychologically, comes much more from a very close woman friend of mine who had—and survived—cancer twice in high school, and who almost never admits to anyone, even now, that she was ever ill because of the fear of being seen differently, and pitied or treated awkwardly or with kid gloves. Also, when I was in chronic pain for three years, where every single day was kind of an unremitting physical struggle, it very quickly became exhausting to me to be asked “how are you feeling?” by well meaning people, because the answer was never what they hoped to hear or what I wanted to say and was never new. I learned very quickly to hide how badly I was feeling if I wanted to be able to interact with people about anything that was remotely compelling or interesting to them or to me, because illness and pain are, while brutal and horrible, also in some ways relentlessly boring. No one wants to be defined by having to talk to their friends and lovers and colleagues as though they’re at a doctor’s check up. People who live with their illnesses every single day are often sick of the way illness dominates. When Mary goes to London and takes Nix’s name and doesn’t tell anyone she meets that she has CF, she is hoping…well, she is hoping for reinvention and escape, not so much because then she can believe she isn’t dying, but because then it might be possible for her to live as though she isn’t just in some suspended animation or Waiting Mode, but as though things are possible for her. And what she finds, oddly, is that of course they are. That all any of us has is this moment, this day.

What’s obsessing you now and why? What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

I’m working on a new novel called Every Kind of Wanting, which is about two gay men who decide to become parents and pursue a gestational surrogacy…but that’s just part of where the novel goes. It spans thirty years and parts take place in Venezuela and other parts in Chicago, on Beaver Island in upper Michigan…it’s about family secrets, and about losing and finding various forms of desire, and about birth and the body and death and the things we carry, because all books I want to read are about all of those things. Like A Life in Men, it has multiple points of view, and unlike A Life in Men maybe it doesn’t have a “protagonist” in a traditional sense but is a true ensemble piece, which is different for me. It is also, in my own admittedly weird opinion, very funny. It’s goofier than other books I’ve written, even though parts are serious or even dark.

And if you asked me anything else, your audience would kill you, as clearly I never shut up.

Published on February 05, 2014 08:53