Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 118

December 9, 2011

Tamar Cohen talks about learning to like the public side of being a writer

I love this post with a passion. Tamar Cohen's a wonderful author (go out and read her darkly funny and richly imagined The Mistress's Revenge if you haven't already) and I was thrilled that she wanted to write something for my blog. She could have been writing about my life! The oddness of being a solitary writer who suddenly has to "go out of the house" and speak and perform and be "on" all the time, is captured perfectly and wittily here. Thank you, Tamar!

On Monday night I went to hear the celebrated Turkish novelist, Elif Shafak, talk about her books and her characters and the meaning of love. She was beautiful, impressive, articulate. She made jokes in two different languages. She told anecdotes about her grandmother, shared her thoughts on identity, and on the concept of home. She took questions from the floor and replied coherently and generously and made the questioners feel validated and special. Afterwards she signed books and chatted to people she'd never met and answered the same questions over and over again without her smile once slipping.

Now here's the thing – if Elif Shafak was a politician or a film star or a motivational speaker you wouldn't be surprised. But she's a writer. For 99 per cent of our lives, we're expected if not encouraged to hibernate inside our own homes, dressed in pyjamas and ugly fleece-lined boots and refusing to answer the phone, insisting instead that all communication be done remotely via the medium of email and Twitter. Yet, for the remaining 0.1 percent, we are expected to magically transmorph into public figures, at home in front of an audience, dressed in clothes without egg stains down them, able to converse on a range of topics in voices that haven't atrophied from under-use, and to remember not only our own names, but also interesting and relevant anecdotes, all delivered with a winning smile.

It was a huge shock for me when my debut novel The Mistress's Revenge came out in June this year to realise that certain things were expected of me as a published writer. There were meetings and parties to go to, people to impress, questions to answer (often the same questions, again and again), intelligent points to be made, books to be signed. And all of these things took place outside of the house! After months spent holed up in a back room, hunched over my computer with only the dog for company (and believe me, my dog's conversational ability leaves a lot to be desired), it was like entering into another space/time dimension.

Now, I'm not saying most people go into writing because they're socially inept misfits who can't handle the real world but… oh who am I kidding, that's pretty much what I am saying. But the great paradox of being published is that, having gone into writing because you're naturally a shy retiring type who prefers tweeting to chatting and doesn't own a single pair of trousers that aren't elasticated at the waist, the payoff for success is that you leave all that behind and go out into the world to be on show – the very thing you hoped to escape by becoming a writer in the first place.

I'm a truly terrible public speaker. Give me an audience of any type and my tongue becomes velcroed to the roof of my mouth, I say things like 'um' a lot or else make a strange nervous humming noise. I start sentences with no clue of how they might end. I also develop a rather disturbing giggle. The thing is I've never been taught how to do it. I like to see things written down, I like to play around with words and sentences until they're exactly how the way I want them to be. That's why I write. When I speak, it comes out in either a trickle or a gush, I get words wrong. I gesticulate madly (even if I'm on the radio). My mind goes blank. Doing a series of live radio interviews to publicise the book in the USA a few months back, I took to placing a sheet of paper in front of me with the names of my main characters written in big capital letters, after embarrassingly getting one of them wrong on my first attempt.

God knows how big-name writers go into television studios to perch on sofas and talk knowledgeably in front of audiences of millions. How on earth do they know what to wear? At home I have a Writing Cardy, an outsized, woolly moth-eaten cardigan that sits draped over the back of my chair and that I put on over the top of whatever I have on (usually garments of the 'leisure-wear' variety), basically because I'm too mean to put the heating on when it's just me in the house. This is what I spend most of my life wearing. After publication, not only did I have to step away from the cardy, I also realised that none of my other clothes would stand up to public scrutiny. Things had to be bought in a hurry and chosen according to criteria other than whether they were a) comfortable and b) able to accommodate a pair of wellies for the daily dog walk. For the first party after I'd been signed by my publisher, I bought a pair of shoes with sky-high heels and spent the night grimacing rather than smiling at important people I was introduced to and hardly able to talk for the pain. I suspect the collective verdict was that the company's latest signee was clearly a sociopath.

But you know how they say you can get used to anything? Well, the truth is that after a couple of months blinking in the unaccustomed light of an external environment in my non egg-stained clothes, I started to quite like it. I relaxed enough to throw out my characters crib-sheet when I did interviews, and stopped feeling like a child dressing up as a grown-up whenever I ventured out to work-related events. So it was a bit of a rude shock to find myself, after a whirlwind couple of months, back at my desk in the Cardy, writing Book Two and once again wisecracking at the dog (a wasted exercise if ever there was one).

The last year, since The Mistress's Revenge was accepted for publication, has been the steepest of learning curves in so many respects. But perhaps the one thing I was least prepared for was this schizophrenic arc of the published writer's life. Next time, hopefully, I'll be more ready for it. Next time I'll step seamlessly from the solitary subterranean fug of my home-office straight into any number of public situations and be impeccably dressed and effortlessly impressive in the style of Elif Shafak. I'm working on the bilingual jokes as we speak. The dog thinks they're great!

The Mistress's Revenge is published by Free Press (Simon & Sc

Published on December 09, 2011 08:46

November 28, 2011

The editors of "Men Undressed: Women Writers and the Male Sexual Experience" talk about sex scenes, male critics and more

How could I possibly resist wanting to talk to the editors (Stacy Bierlein, Gina Frangello, Cris Mazza and Kate Meads) of the provocative Men Undressed: Women Writers and the Male Sexual Experience? The book is a terrific collection of bold, brave and brash essays from such extraordinary female authors as A. M. Homes, Aimee Bender, Tawni O'Dell, Gina Frangella, Cris Mazza, and many more. Thanks to all the editors for talking with me.

CL: So, what made you decide to gather women writers to write about the male experience?

Cris Mazza: Someone said to me, as the controversy over the title Chick-Lit for the first anthologies I co-edited subsided, that maybe it was now time to do Dick-Lit. Ha-ha, I said, as though that hasn't already be done in so many anthologies since the onset of printing presses. But … there was a way in which the "male experience" hadn't been anthologized.

At first, I was also playing amateur psychologist. I wanted to see if the way women wrote sex from a male POV said anything about how they themselves view sex – something about their attitude that wouldn't be consciously available, even to them. This curiosity, of course, could not be satisfied because I had no way of knowing if any assumption I could make after reading their material was, in fact, anywhere close to plausible. And, quickly, the initial curiosity that launched the project quickly changed when I discovered (a) many women didn't even write graphic sex, let alone from a male POV, (b) many submissions claimed to have graphic sex and didn't, (c) other anthologies of "women's sensual writing" or "women's erotic fiction" completely ignored the issue of perspective or point-of-view and men exploring sexuality from anywhere other than their own experience. Some of my old bells started re-ringing: the comment a male editor had made to my then-agent about a male perspective sexual situation, a general lambasting at a women's-writing conference from a woman-of-color who said no one else had the right to imagine or depict of character outsider her own cultural reality. [Note: co-editor Kat Meads has a new book out in which she did exactly this. http://www.katmeads.com/] I decided to go see what was out there and what might be said of it if I gathered it together under one cover.

Kat Meads: My motivation was similar to Cris's. I get very perturbed when critics or reviewers or readers start making rules about what can and can't be written about. Very perturbed. I'm truly stunned and amazed that anyone would suggest/demand restrictions on a creative composition. Imagination: no creed, no color, no age, no gender. Anything and everything up for grabs. Does it work/convince as a piece of fiction? That's what counts, the only judgment that matters. But when Cris and I started thinking about and reading for this project, it was clear to us that a particular kind of censorship—either absorbed or self-imposed—was operating in terms of women writing from the male viewpoint about sex. And I think both of us—and then all four of us—were a bit taken aback by the difficulty of finding work that met our vision for the book. But when we did find those stories and novels, we were ecstatic. In Men Undressed, women not only write as men about sex, they write very, very well.

CL: What kinds of stories did you expect to receive and were you surprised at what you got? I'm also curious what direction you gave your writers, and how you chose the stories you chose.

Stacy Bierlein: Several colleagues asked, "Are you sure about this? People write so badly about sex." But I didn't believe that. A well-written sex scene can be central to any powerful literary work. Sex scenes are often an ideal means for both writers and readers to really know a character. In the 1700s male writers like Samuel Richardson got to know their female narrators by writing their soul-baring letters. This was a time of high censorship, so these letters likely stood in for sex scenes that would have prevented a novel's publication. (It's interesting to note too that Richardson's work inspired more than one American clergyman to call fiction itself "a sinful form of writing.") In our age of texts and tweets, our characters do not write soul-baring letters, but certainly writers can put their characters in sex scenes to reveal their most intimate, honest, or horrifying selves. Certainly as writers we can attempt these moments that allow heightened power to details. The guy who reaches for his Blackberry before his partner has finished coming …. Well, we know exactly who he is. (It's better to be writing him than dating him, of course.) As we began work on our book, we asked writers for works of literary fiction with "frank sexuality." It took our attention that in the early months of our reading for Men Undressed we received strong, deeply admirable stories that were highly sensual yet void of real sexual tension or actual sexual encounters. Our associate editors got a little tired of the four of us saying things like, "Great story, but my god, why don't they fuck?" And to be honest, due to the high quality of some of the not-quite-sexual work we were rejecting, I wondered on several occasions if we might consider altering our mission for this book. Certainly "narrative cross-dressing" on its own was a formidable topic. Cris, Kat, and Gina held firm to the frank sexuality requirement and they were right to do so. We chose visual stories that held us in awe, stories whose vibrant characters pushed at us in some way, and stories we envied and wished we had written. I think the results are stunning.

CL: Why don't men--and some women--want women to write raunchy?

Cris Mazza: I'm breaking this question down to "why do so many writers avoid graphic sex?" I believe some writers, male and female alike, might fear the appearance of using graphic sex only to amp up a book's "drama" – that old "only for prurient interest" criticism which, outside obscenity court cases, just means sensationalizing, on par with including graphic violence and gore. Some, perhaps, fear always being associated too closely with their characters and don't want to feel that readers are able to peer into their own private intimate lives. Some men likely don't want their writing to live in the same sphere as locker-room one-upmanship. But when it comes to what you've actually asked, why don't men want women to write frank sexuality …? Okay, you said "raunchy," and I find I can't apply that word to the category of sex-writing I'm talking about; and that's why I'm demurring. Raunchy is defined as vulgar, crude, coarse, gross, etc., and we're right back into that court definition of obscenity.

Staring over: Why don't men want women to write graphic or frank sex scenes? Porn video makers in the 70s and 80s included some girl-on-girl scenes because men are very interested in women expressing their sexuality. (Hey, have there been any women porn film makers?) But publishers and editors and critics? Somehow many were infused with or confused by a standard their mommies taught them for what kind of girl they should marry. A virgin who would never use a "bad word" or even refer to her own body parts (or his) and wants to get undressed in the dark.

OK, I know I'm being snarky. I don't know if men don't want women to write sex scenes. I do know that some women writers simply said to me, "I don't do that," as though I'd asked them if they like to have sex in public.

Gina Frangello: I'm not sure that men don't want women to write sex scenes, exactly. What I do think is that "the market"—which both men and women are responsible for in different ways—tends to discourage literary women writers from focusing much on sex, whereas it actually very much encourages female genre writers—whether romance or pop or chick-lit or even thrillers—to write more overtly about sex. This is so complex, really. I'm not that much younger than Cris but we did come of age, so to speak, in a different literary era, and in my formative years as a writer/editor there was no huge shortage of women writing sexual fiction—some of my influences were Mary Gaitskill, Kathy Acker, Kate Braverman, really many women writers by the early 90s were writing candidly about sex, I sometimes think more so than in today's market. This was just on the brink of the wide-scale corporatization that took place in the publishing world, and it was also prior to 9/11 and the economic downturn, both of which had a somewhat "Puritanizing" influence on the publishing world (as well as on other art forms such as film).

Between the fact that trade publishing is now almost synonymous with shareholders and marketing teams making more decisions than editors, and the fact that there started to be this prevailing belief post-9/11 that audiences couldn't stand anything other than "feel good" or simple, inspiring stories, I think the truth is that bold, risk-taking art forms have really suffered pretty much across the board. In my view, serious explorations of sex in fiction has been a casualty of these developments. In the 90s, you had even mainstream magazines like Vogue talking about "perversion chic"—Quentin Tarantino was all the rage in Hollywood.

The post-9/11 landscape, paired with what corporatization and economic recession did to the publishing world, really changed that cultural zeitgeist. I think this has far less to do with men as a sweeping gender discouraging or disapproving of women talking about sex, and much more to do with an actually (much more discouraging) move away from serious art on a wider scale and with an anti-intellectual movement in the country. Women are still writing plenty of sex. But they're not encouraged to do so in a serious way, outside of beach reads. With the downsizing of serious art/literature in the United States, it seems to me that sexism has reared its ugly head in a way that would have seemed passé in the 1990s. There are fewer and fewer "slots" available to writers of literary fiction, and among those writers only a certain number can also be edgy, risk-taking writers who are pushing the boundaries of convention with graphic content, and among those writers even fewer can be women because the publishing industry seems to accept without question that male work is Universal whereas female work is "for women."

I guess, Caroline, I think this question is almost unspeakably complex—it's fascinating to me so I have to put the brakes on myself. There are a few trade publishers out there, like Algonquin and Harper Perennial, that still seem to really be encouraging writers to take risks and that seem very open to women writers with big, bold or subversive ideas, but this seems to be less and less prevalent due to the current Armageddon in publishing. People are going with the safe, the crowd-pleasing, and a lot of women writers are being ghettoized, with literary fiction becoming more a boy's playground than it was in the 1990s, paradoxically. And in this vein, women writing frankly, graphically and honestly about sex has never been exactly "safe." Which is why it's more important than ever right now.

CL: How have male critics responded. Has there been any, "How dare you!" type of response? (And, by the way, I loved the foreword by Steve Almond.)

Gina Frangello: Well here's the irony, really. My personal belief is that once a book is published—once it's been given that "stamp of approval" by being in book form, the general public tends to be far less aghast by it than marketing departments might have imagined they would be. A lot of people seemed to believe, going into this project, that we were going to get some serious flack. However, that hasn't actually proven true thus far. I did see a fairly heated exchange on the Facebook wall of one of our contributors, where some of her male "friends" were agitated by the book's concept. They felt it was reverse-sexism and that the book was going to be all about turn-about being fair play or about a reaction against male writers or men in general. But the fact is, these guys hadn't read the book; it wasn't even released yet. I think it would be very hard to come to a conclusion like that if they had.

While the male characters in the anthology are often flawed—as all great literary characters are—the anthology is a celebration of male sexuality, not an indictment. The women writers we selected are grappling mightily to understand men and get inside their skin in a visceral way. Steve Almond remarks, as you note, that we are sorely in need of that understanding, and I think that's precisely true. No critics have yet disputed that or taken issue with it. I'll be somewhat surprised if things play out in that way. The women in Men Undressed aren't just trying to get revenge on D.H. Lawrence or something. They feel their characters very deeply and care about them and breathe life into them. Some of these women—like A.M. Homes, for example, were at the forefront of launching this new literary tradition, in which women are equally free with men to explore the Other. There's much to debate on the pages of Men Undressed, but I don't think anyone who really cares about literature—as obviously critics do—would dispute the right of women writers to do that.

CL: Do you think male writers and female writers have different ideas on what makes a good sex scene? In reading these stories, I actually thought the writers were really more interested and focused on individual character, rather than trying to reveal the male at large, Could you talk a bit about that?

Gina Frangello: I'm not sure if male and female literary writers have different conceptions of good sex scenes, broken down cleanly into gender. Certainly it does seem that there are ways of portraying sex, i.e. much of the porn industry on the male side, or romance novels on the female side, that appeal strongly to one gender and less strongly to the other. But is this true in so-called "literary fiction?" I'm not sure. I think of someone like Mary Gaitskill, who is just a master at writing sexuality, and it seems to me that she has as many male fans as female fans, even though she's a woman writer. So I think the further away from stereotypes—and the closer to "individuality"—the art form becomes, the more it actually eschews a gendered definition, you know?

Which actually ties in to the next part of your question, Caroline, because yeah, on the one hand our anthology is intended to focus on how women writers may envision Male sexuality, capital M. As a compilation of 28 pieces of fiction, we hope to be able to launch discussions about that. But on an individual, story-by-story level, I doubt that was any writer's singular intent. What I mean is: the focus on individual character, rather than some concept of "male at large," is probably why the stories/chapters we chose are so strong.

If a story attempted to capture the "male experience" in some global sense, it would likely be disastrously didactic and annoying. After all, what would we think of a male writer who was trying to capture the "essence of woman" in his fiction, as opposed to writing about an individual female character, right? Even in the example of Lady Chatterly, which—as Cris Mazza points out in her Introduction—may have misled many women readers over the years in terms of being a role model of female sexuality, we have to remember that Lawrence was only positing that one woman might have this sort of experience, not that all women were Lady Chatterly. And as Cris also points out in her Introduction, this is the task of all fiction, really.

It's always about the individual character, even when you are writing about a gender, race or ethnicity to which you as a writer also belong. Toni Morrison may be a black female, but her character, Sethe, in Beloved is not meant to be Every Black Woman. Imagine the critical outrage if Morrison had been implying that Every Black Woman would murder her child! But she was writing about one woman, and therefore her task was to make this action believable, resonant, and even understandable in that one character's eyes and circumstances—and she succeeded brilliantly. That's all any writer can ever hope to do unless they're conducting a clinical study, not writing a piece of fiction.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Stacy Bierlein: I realize this echoes some of what we have discussed here as well as Steve Almond's forward, but for the writers reading this interview I would suggest again, Why not write about sex? It baffles me how many writers still avoid or dismiss this vibrant and important arena in their work. In an era where we have so-called leaders discussing things like abstinence-only education for young people, there is precious little frank discussion of sex as a means of self-exploration or self-expression. For many characters on the pages of Men Undressed, sex is that and more.

Kat Meads: Stacy Bierlein: Indeed!

Published on November 28, 2011 13:39

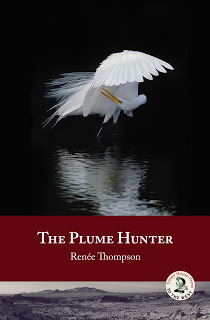

Renée Thompson talks about The Plume Hunter

Renée Thompson writes about her love of birds, wildlife, and the people who inhabit the American West. Her first novel, The Bridge at Valentine, received high praise from Pulitzer Prize-winning author Larry McMurtry, author of Lonesome Dove.--but more importantly, at least to me, she's also warm, funny, and a wonderful friend. Her second novel, The Plume Hunter, about conflict, friendly, love and plume hunting (killing birds to sell the feathers for hats) is due from Torrey House Press on December 1. I'm honored to host her here.

Renée, I'm intrigued. I've heard of plume hunters – which I thought existed only in Florida. Yet your book is set in Oregon? I know, Caroline – it's a surprise, right? Most readers assume that birds were killed strictly in Florida, but plume hunters also shot birds in other regions of the country, including the marshes of Klamath and Malheur, in Oregon, where my novel is set (Portland also plays a small role).

What kinds of birds did they shoot? Great egrets (hunters were attracted to the "bridal plumes" on the birds' backs during breeding season), snowy egrets, western grebes, pelicans, terns, owls, and all sorts of songbirds and shorebirds. In the winter, market hunters in Oregon and California also shot thousands of ducks for the restaurant trade in San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle.

What inspired you to write a novel about plume hunting? I was intrigued by a photograph of William Finley and Herman Bohlman, who, in the late 1800s were oölogists (egg collectors) in Portland, Oregon, but who turned to photography when egg collecting became unpopular with bird lovers. About the same time, I saw a historical photo of market hunters with their kill, and something just clicked. I did some research, and learned that in 1885 more than five million birds were killed in the United States alone for the millinery trade. When I read that feathers sold for $32 an ounce – which in 1903 made plumes worth about twice their weight in gold – I knew I would craft a story about a plume hunter and his best friend – someone stalwartly opposed to pluming – and that their differing philosophies would provide conflict, and help propel the plot.

Can you tell us more?I don't want to give away too much, but I will say that at its core, Plume is about two best friends who are torn apart by their differences; Fin is Plume's dark hero, and Aiden Elliott is his best friend, a man who considers himself the birds' savior. I'll also mention that it was an interesting paradox that men who collected eggs and bird skins in the name of science – often for museums – didn't see themselves as contributing to the demise of birds, since they weren't "real" killers, but men furthering the understanding of our avian world. To that end, I've also incorporated a fictionalized version of Frank M. Chapman, who, in real life, was the curator of birds for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Chapman was instrumental in the re-formation of the Audubon Society after its failed first start, so I've cast him as Aiden's mentor.

Where does that leave Fin?That's actually a pretty important question. Fin loves to hunt – it's in his blood and bones. Still, he struggles to understand if it's hunting that fuels his soul, or the actual killing. I think this is a question some hunters ask even today, and so I've explored it in Plume, allowing readers to decide for themselves the moral implications.

Speaking of moral implications – am I giving away too much by saying Fin and Aiden fall in love with the same woman?Not at all – we just won't let on who gets the girl, or what it costs the "winner"!

Published on November 28, 2011 13:27

Amy Bourret talks about Mothers and Other Liars and the novel experience of being a novelist

A young drifter. A baby. A split second decision that will have ramifications for all involved. That's the subject matter of Amy Bourret's incredible new novel, Mothers and Other Liars. I'm thrilled to host her here on my blog writing about the experience of having a novel out! Thank you so much, Amy.

Novel Experience

The first one was sent to me through my publisher before my novel was even published. A woman had received an advance copy of "Mothers and Other Liars," and just had to write to tell me that she loved my book and couldn't get my characters out of her head. I was thrilled! I have been a voracious reader since I could read and can't think of a time I wrote to an author just to say I loved a book. I'm sure "famous authors" get them by the bagful. But here was nobody me holding an honest-to-goodness fan letter.

The letters have continued to arrive. Granted email, websites and facebook make it easier, but some readers have taken the time to put actual pen to actual paper and sent them with actual postage stamps: "I don't even know what to say……what a moving, wonderful story"; "I just wanted to write and say thank you for sharing your story with me"; "I wish to congratulate you on writing such a thought-provoking and beautiful story"; "I am still walking around days after finishing wondering what I would do if I were in Ruby's shoes."; "Your debut novel is a journey through betrayal and forgiveness, secrets of the past, and the love and dedication that defines 'family'"; "I stayed up all night reading"; "WOW. I just finished Mothers & Other Liars, and I had to email you to let you know how much I loved every single word of it"; "Thank you so much for the amazing novel Mothers and Other Liars, the book is such a gift;"

The true gift – and genuine surprise -- for me has been receiving these letters. People are busy trying to cram 42 hours in a 24-hour day. I already thought that being invited into a person's home, to have my words sit with her in a cozy corner for a few hours, was an honor. And now for her to take even a few more minutes out of her day to write words back to me? Ironically, I have difficulty crafting the words to describe how meaningful that experience has been for me. Even the hate mail, like "You obviously have no maternal bone in your body" or "You may write pretty words but you sure can't tell a decent story" tells me that my book has touched someone enough for her to remember it after the last page (how many times have you read a book that afterwards you couldn't describe?) and aroused enough emotion for her to follow through and write to me.

I thought I had prepared myself for publication. I stocked up on blue pens and pithy comments for book signings. I knew I would love talking to book groups and listening to them debate the choices made by my main character, Ruby. Writing happens in a vacuum, just me, my keyboard and an empty room, so feedback about characters and plot and, yes, petty words helps me to write better. But the letters, this unexpected gift from the hearts of readers, has been such a novel experience.

Amy Bourret is a graduate of Yale Law School and Texas Tech University and a former partner in a national law firm. Her pro bono work with child advocacy organizations sparked the passion that fuels Mothers and Other Liars, her debut novel which was, selected as a Target Stores Breakout Book. She loves to visit book clubs and hear from readers. Learn more at www.amybourret.com .

Published on November 28, 2011 13:09

November 20, 2011

Five reasons to see Answers to Nothing, coming Dec 2.

I'm a confirmed movieholic and nothing makes me happier than a wonderful film. I was honored to have had a chance to see a screener of Matthew Leutwyler's astonishing film, Answers to Nothing, opening December 2. Because I want everyone on the planet to see the film so I can talk about it with them, I've come up with five more reasons why you need to see it.

1. Dane Cook's revelatory, nuanced, heartbreaking performance.

2. And for Dexter fans, there's Julie Benz (Dexter's wife Rita!) Actually, the whole cast is just sublime.

3. Intertwined stories with fascinating characters: a single parent detective looking for a missing child; a pregnant wife dealing with her husband's infidelity, A cop haunted by his wife's death, a self-loathing African-American, and a school teacher with a jones for video games who is obsessed by the crime.

4. Because Matthew gave me this great interview.

5. And how about the fact that Matthew Leutwyler is just so cool? Says he: "It's uncomfortable to expose your inner workings, but it just feels more authentic." And isn't that what we all look for in art (and in life?)

Published on November 20, 2011 15:21

November 14, 2011

Pictures of You on Kirkus Best Books of 2011 List!

I am sitting here unable to work because I'm too excited. My novel Pictures of You was just chosen for the Kirkus Best Books of 2011 List! What is so astonishing to me is that from the moment I went with Algonquin, my whole life changed. I went from someone with meager sales to being a NYT bestseller, a Costco Pennie's Pick, a San Francisco Lit Pick, a Best Book of the year from Bookmarks Magazine, Bookpage AND Kirkus--and I think it really goes to show that you cannot give up. You cannot ever give up. You never know what miracles are out there.

Published on November 14, 2011 10:51

November 9, 2011

Leora Skolkin-Smith talks about madness, Grace Paley, resisting writing about what you need to write about, and Hystera

I first met Leora Skolkin-Smith through Readerville, an online literary community and we quickly became friends. We talk about writing all the time and I've been thrilled to see how Leora's first novel Edges is now edging its way into becoming a feature film from Triboro Pictures. Her new novel, Hystera, about madness, youth and NYC in the 1970s, is from the Fiction Studio Imprint, one of the more exciting new publishing venues around. I'm honored to have Leora come on and talk about her book--which debuts November 15th! And don't forget to listen to Leora on Reading With Robin, this Saturday, 92WHjj, 7 to 8 AM.

What sparked the idea for the novel? Where did it come from?

I once heard the German writer Christa Wolf speak on a panel, long ago, when her "The Quest for Christa T." first came out in East Germany. This book was banned immediately and as she wrote it, she had no belief it would find print. She said something even more interesting--she said, first she had been working on another book she knew would sell and be read, but this one, Christa T. kept looming up and haunting her instead. She had such a resistance to writing anything like it, to the unconscious, disturbing material inherent in it and she could feel that resistance so strongly, like a brick lodged inside her gut. Her resistance was overwhelming and so she had to try to understand it., or she would never be able to write the "sellable" one. She asked herself: What was it she was so scared of writing? What would she expose if she wrote? What material didn't want to surface from deep inside her? Was that too frightening? Too raw? Too passionate? All of these things could make a writer terribly uncomfortable and cause such a resistance. The only way she could concentrate again was to write out what she was so afraid of. Express what about Christa T. made her fight so hard against knowing her character and her character's situation. And she wrote the book against all better judgement. And it was the best work she ever had done. Drive and force and passion to tell it broke through the resistance in the end. And that is the energy one needs to really write a meaningful book.

So now, she explained, when she asks herself, what should I write? The answer is: write the story you are most resisting, that is the one you truly must tell.

For me that was HYSTERA. And for all the same reasons Christa Wolf resisted telling the story of Christa T.

What kind of a writer are you? Do you map things out or do they come organically?

I'm a big messy spiller of paints. I love images, I have images come to me way before story. Images and fragmented senses. Sometimes just smells. I work from impressionism purely. I wish I could be someone who plans and structures with plot, but...that just never happens for me. Plot is the very last thing that happens.

You have a feature film coming out for your last book Edges. Has being involved int he film process changed the way you look at writing novels?

I love working on the feature film. It stretched all the boundaries, I learned so much about how a screenwriter must visualize and communicate the same feelings embedded in words alone inside a novel and I think that helped my work as a novelist. Plus, it's all so exciting. I felt an affirmation I hadn't felt in the literary community, a welcome mat.

What's obsessing you now?

I'm trying write about a relationship I had with Grace Paley. Since I was very close to her, I was witness to a whole lot of circumstances and saw up close what happens to celebrities and beloved writers who are fundamentally literary, but used, exploited by others and the media to create them as icons, in false pictures. It's a challenge because I could get in a whole lot of trouble doing it. Most of the characters are well-known. It's a roman a clef. Very hard but fun in that revengeful way one can't ordinarily express, having to be a "lady" or a "nice person".

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Can't imagine! These were great!

Published on November 09, 2011 10:43

November 7, 2011

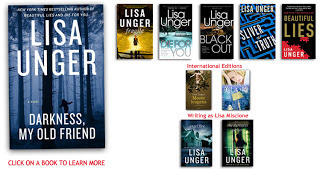

Lisa Unger Talks about where it all began

New York Times bestselling author Lisa Unger really needs no introduction. Is there anyone on the planet who doesn't know her? Her novels have sold over a million copies and have been translated into 26 languages. Her new novel, Darkness My Old Friend, about the secrets of the past and the future of a rebellious teen was chosen as a Washington Life Magazine Lit Pick. I'm thrilled she's agreed to write a little something on my blog about her beginnings as a writer. Thank you, Lisa!

New York Times bestselling author Lisa Unger really needs no introduction. Is there anyone on the planet who doesn't know her? Her novels have sold over a million copies and have been translated into 26 languages. Her new novel, Darkness My Old Friend, about the secrets of the past and the future of a rebellious teen was chosen as a Washington Life Magazine Lit Pick. I'm thrilled she's agreed to write a little something on my blog about her beginnings as a writer. Thank you, Lisa!PrefaceByLisa Unger

I was nineteen years old when I first met Lydia Strong. I was living in the East Village, dating a New York City Police officer and attending Eugene Lang College, the under graduate division of the New School for Social Research. I was sitting in a car, under the elevated section of the "1" line in the Bronx, waiting – for what I can't remember. But, in my mind that day, I kept seeing a woman running past a church. She was in New Mexico. And all I knew about her was that she was a damaged person, someone in great pain. Running, for her, was salve, religion, and drug. That was Lydia. I pulled a napkin and a pen from the glove compartment and started writing the book that would become ANGEL FIRE. It took me ten years to write that novel, mostly because the years between age nineteen and twenty-nine were, for me, years of hard work and tumultuous change. But also because during that time, I let my dreams of becoming a writer languish a bit. Lydia was faithful; she waited. In spite of a first rate education, a career in publishing, and a strong desire to write fiction, I didn't know much of anything when I was writing my first novel. I don't think you can really know anything about writing a novel until you've actually written one. (And then you go to school again when you sit down to write your second, and your third, and so on.) All I knew during that time was that I was truly fascinated by this woman occupying a place in my imagination, and I was deeply intrigued by her very dark appetites. I was enthralled by her past, by the mysteries in her present, and why she wouldn't let herself love the man who loved her. There were lots of questions about Lydia Strong; and I was never happier over those ten years then when I was trying to answer them.I was fortunate that the first novel I ever wrote was accepted by my (wonderful, brilliant) agent Elaine Markson, and that she fairly quickly brokered a deal for ANGEL FIRE and my second, then unwritten, novel THE DARKNESS GATHERS. I spent the next few years with Lydia Strong and the very colorful cast of characters that populate her life. And I enjoyed every dark, harrowing, and complicated moment with them as I went on to write TWICE, and then SMOKE. I followed Lydia from New Mexico, to New York City, to Albania, to Miami and back. We trekked through the abandoned subway tunnels under Manhattan, to a compound in the back woods of Florida, to a mysterious church in the Bronx, to a fictional town called Haunted. It was a total thrill ride, and I wrote like my fingers were on fire. I am delighted that these early novels, which I wrote under my maiden name Lisa Miscione, have found a new life on the shelves and a new home with the stellar team at Broadway Books. And, of course, I am thrilled that they've found their way into your hands. I know a lot of authors wish their early books would just disappear, because they've come so far as writers since they first began their careers. And I understand that, because we would all go back and rewrite everything if we could. But I have a special place in my heart for these flawed, sometimes funny, complicated characters and their wild, action-packed stories. I still think about them, and feel tremendous tenderness for even the most twisted and deranged among them. The writing of each book was pure pleasure. I hope that you enjoy your time with them as much as I have. And, thanks, as always, for reading.

Published on November 07, 2011 07:26

Julie Klam talks about Love at First Bark

Ok, you might love Julie Klam because she's so hilarious and generous, but the icing on the cake is that Julie is the guardian angel of dogs everywhere, and she's made it her mission to show us all how fostering and loving dogs can really make us better people. Plus, she knows Timothy Hutton...need I say more? Anyway, I'm deliriously happy to have Julie back on my blog. Thank you, Julie!

I love the whole idea that dog rescue is a two-way street, in that it impacts both the dogs and the people doing the rescuing. How does that work? (And does it ever backfire?)

I think if you rescue animals, you're rewarded, you can't help it. Specifically in this book I was thinking about when times are hard and you feel you don't have control over things and you can do this one small gesture which actually isn't small at all, and make all the difference in the world. It's empowering and validating and it doesn't cost you anything.

I need to ask (because I am insanely jealous) about that hilarious book trailer you did with Timothy Hutton.

Okay, truthfully, Tim and I are secretly in love. In fact it's such a secret that he doesn't even know it. Honestly we had a mutual admiration society going, mutual in that I loved him and he was drunk when he said he'd be in my book trailer.

I always thought that people loved their dogs simply because they got unconditional love, but your book shows that it is really so much more than that. Dogs teach us to cherish each moment, to never give up, to be loyal, and more. Is there anything else I'm missing?

You forgot how to cook french food. Oh, no that was Julia Childs.

How can regular people get involved?

Regular people as opposed to insane losers like me? When you contact a rescue group, you can be as involved as much or as little as you want. You can do very small, simple things like making phone calls, doing home visits to prospective adoptive families, reference checks, fundraising. You don't have to foster dogs, though doing it is insanely wonderful.

How did all your rescue work change you personally?

I think like any volunteer work it makes you conscious of how much there is to do in the world and how few people there are to do it.

Can you talk about your NPR radio show Hash Hags?

Ann Leary used to do a show on NPR that was just her and one day she asked Laura and I if we would do it with her. It's ridiculously fun, we get great guests and having been on the other end of those author interviews where the person asks you the standard questions, we try and make it a little different. And once a week I get to talk to Ann and Laura, what could be better than that?

And the questions I always ask, What's obsessing you now?

I just got back from my book tour and I bought something before I left that has to be returned within 14 days and today is the 14th day so until it's out of my hands I'm going to be obsessed.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Everyone else has asked me if my husband is some kind of saint or something for allowing me to wreak the havoc in the house with all the dog rescue that I do. I'm glad you didn't ask me that[image error]

Published on November 07, 2011 07:25

Director Michael Medeiros talks about his upcoming film Tiger Lily Road

Anyone who knows me knows that I'm fascinated by craft, by how creative people manage to do what they do--and that I am not just a bookaholic, but a movieholic, as well. I first read about the film Tiger Lily Road, Michael Medeiros', upcoming dark comedy about the lives and loves (or lack of) of two Connecticut women, on Google, and I was instantly fascinated. So I immediately tracked him down and badgered him for an interview. I'm honored to have him here. An actor, director, writer and songwriter, Michael's acted in everything from Xmen First Class to Synecdoche, New York to The Good Wife and he's the director and writer of Underground. Thank you so much, Michael.

You're also an acclaimed actor as well as a director and writer. Do you prefer being in front of the camera, behind it or at your desk, and why?

It feels great to switch from one creative activity to another. Sometimes I get to a point where I am thinking, "what the hell am I doing?" I tell myself I have to focus more, but then sometimes it helps to take a break and say, play my guitar, and then come back to film editing. I've been a songwriter since I was thirteen, and sometimes when I get editing fatigue I leave the desk and I play for half an hour and it refreshes me. And editing is, in itself, so much about the musicality.

What do I prefer doing? It depends on the day I'm asked. I just finished acting in a film that a friend of mine is doing, and I really had a good time. The material, the character – makes it a good time. And I got to learn a little big of magic for the role. But I do find that directing films uses all of my artistic resources quite thoroughly.

Tiger Lily Road is about the lives of women in a Connecticut Town—how they perceive themselves and the men in and out of their lives. Where did the idea come from?

Well, the easy answer is I'm not sure. The more complex answer is that it came from several places. After I wrote my film Underground, I wanted to make a feature and I wrote several that just wouldn't have been practical for me to produce. They were too big, too expensive. I didn't want to spend years chasing five million dollars. I wanted to spend months chasing a much smaller amount. So I was looking for that idea, and then I was up at this Connecticut cottage—my girlfriend's family's place—and one night at a party, I got to talking to these women. They were all in their mid to late 40s and none of them happened to be with a man, and I had this epiphany. I kept thinking, what great women they were, how funny and smart and talented. Why weren't they in a relationship? And I thought, "There's a story here." And the story, as it evolved seemed to match up with the whole Connecticut location I loved. I've always found that "place" is one of the strong characters in any story. That probably comes from my acting training with Uta Hagen.

I started imagining –or something started to imagine for me--two women in this house and I started listening to them and following them, and what they were saying, why they didn't have successful love lives. And then these two women began to split off in different directions, and these two best friends began to be complete characters. And as total opposites, I could use them to dramatize two sides of the same question.

On a deeper level I think the impulse to write it came from a need to express something about women - about how they empathize (or don't) with men and what that may cost them.

How do you write? Did you map this story out or did it organically evolve?

It was more organic. As in song writing, I go until the structure reveals itself. I don't try to impose it too soon. I always allow that this may only ever be a fragment and then at some point, something clicks in and I know I'll finish it and have an understanding of how.

Did any of the women that sparked the idea read the script? What'd they think?

Well, the characters are not really them. I used the voice, the sensibility, but not the circumstances.

How long did it take to write Tiger Lily Road?

It was about a year and a half from first draft to shooting script. In that time, many people read it and gave notes—some of them quite scathing! I also did four different table readings with full casts of talented actors.

What's fascinating to me is that you are making people out in the world part of the process by posting snippets from the film and asking for reactions. What's the response been like?

It's been fantastic. I have to be careful what I show online. I don't want to give things away, but it does help to build a fan base.I'll be putting up a highlights reel in the next couple weeks. You'll be able to see it by going to: www.bennettparkfilms.com or by liking us on Facebook at tigerlilyroadmovie.

What's obsessing you now?

Distribution. Finding the audience. Realistically, you have to seek the distributors. But now that there is this entire social media thing, it's a little easier to create a presence before the film is ever released. But it's a lot of work. Eventually, the film will have its own website. But now, at this mid stage of post production, I make a lot of lists - of theaters, distributors, possible supporters.

Question you didn't ask: Who's in the movie?

An amazing cast, including: two time Emmy winner, Tom Pelphrey (a rising star if there ever was one), talented stage actresses, Ilvi Dulack and Karen Chamberlain. I wanted to use theatre trained actors for their ability to conceptualize complex characters. And New York theatre legend, Rita Gardner who starred in the original production of The Fantastiks with the late great, Jerry Orbach. Rita is in danger of stealing the entire movie.

Published on November 07, 2011 07:25