Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 108

August 12, 2012

Jonathan Evison talks about The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, forgiveness, being the luckiest guy on the planet, and so much more

One of the things I love so much about my publisher Algonquin is that I really adore the other writers they publish. we all support one another, cheer one another on, and generally make mischief when we see one another. I first met Jonathan Evison at BEA when I was promoting my first novel with Algonquin, Pictures of You, and he was promoting West of Here. To say he's hilarious, funny, kind, generous is only the half of it. He's also one of the most brilliant writers around with a heart the size of Jupiter.I'm honored to host him here. Thank you, Johnny!

The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving is a departure from West of Here--I think you yourself called it a novel of heart. What was it like taking on such a different novel and did you ever think uh oh, can I pull this off?

You know, I never really questioned whether or not I could pull this novel off. I just had to write it. There was a lot of emotional dredging involved, and that was not easy, but totally rewarding every step of the way—cathartic, really. My hope is that this will translate for readers.

I deeply admired the structure of the book, the way you teased out the answer to the question (what happened to this guy?) while taking us on this wonderful, flamboyant road trip. What was it like mapping out this novel? What did you know about it when you started--and what were some of the surprises?

As silly as it sounds, I envisioned this novel from the very beginning as an artichoke. I just kept peeling back these layers of armor until I got to the heart of the characters. I was really resistant to the idea of writing a road novel, so that was a surprise. The characters forced me to set them in motion—they needed the road to deliver them, and I suppose I needed it, too.

The novel, to me, is so much about forgiveness--self and of others, of how we move on or stay stuck. Can you talk about that? Also, I know that this book has a beating heart that comes from your own experience. Would you mind talking about that, too?

Forgiveness is one of the most powerful and affecting human endeavors, I think, and certainly one of the most cathartic. This book forced me to relive in large measure some very sad and unpleasant experiences, such as the freak accidental death of my sister, and the nearly instantaneous and totally unexpected dissolution of my first marriage. Both of these losses were irredeemable, and yet we really have very little choice but to motor on, right? This book had to be funny. It just had to be.

You are this incredibly generous writer, always championing other writers and indie bookstores, and you also have an interesting backstory. You buried several of your old manuscripts and it took you a few books to get to your NYT bestselling glory. Yet, you are unpuffed up about it, you still sit down and do the work. What keeps you on such an even keel and how can other writers grab some of that attitude?

In a word, gratitude. I feel like the luckiest guy in the world to be doing exactly what I've wanted to do my whole life. And frankly, I'm bowled over by the love and support I've received not just now that I've achieved some level of success, but always. I was quite happy as a starving artist for twenty years. The corporeal realm is all gravy. You've gotta be grateful for every second of it, even the horrible parts. Every single moment of our lives has the potential to make us more expansive people. As far as helping others, it's an honor and a pleasure. I mean, really, you can only do so much to help yourself, at some point you've gotta' help others. Everybody wins.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Whether or not the corn I planted will be alive and knee-high by the fourth of July, or by the time I get back from this tour leg. I'm also obsessed with Melville at the moment because I've been tasked with writing a forward to a new, definitive edition of Typee, and that's a tall order. And, as always, I'm obsessed with British ales.

What question should I be ashamed that I forgot to ask?

You should never be ashamed. You're a peach, with a great big heart and a generous spirit. But since you didn't ask, my very favorite beer is Samuel Smith's Nut Brown Ale.[image error]

Published on August 12, 2012 09:49

August 7, 2012

Laura Zigman talks about Annoying Conversations, her "embarrassing" writing life, tan feet, and so much more

When I first read Animal Husbandry (turned into the film, Someone Like You), I wanted Laura Zigman to be my friend. So you can imagine how thrilled I became getting to interview her for my blog (and I got to be on Hash Hags, the radio show she does with Ann Leary and Julie Klam!) Laura's also the author of Dating Big Bird, Her, and Piece of Work, and she's the hilarious creator of the Annoying Conversations videos. Thank you so, so much for this interview, Laura!

First, did you like the Radcliffe Publishing Procedures Course, because I took it and was yelled at when instead of moving to NYC, I ran off and got married and lived in Pittsburgh for a few years--a big mistake if there ever was one.

OMG. (said with total Mall-Rat tone and big eye roll). I had no idea you took the Radcliffe Publishing Procedures Course too (and yes, you had to say "Procedures" even though no actual "procedures" were taught except for afternoon sherry-drinking.). As you know, it's no longer at Radcliffe, in Cambridge. It's now in New York and called something else entirely. But anyway, after having been rejected from every college I applied to except my safety school (and after being wait-listed, but then rejected, by Vassar, in a letter addressed: "Dear Ziggy"), you can imagine the ego-salve that nice thick acceptance envelope provided when I was accepted.

Like you, I had no intention of ever moving to New York. In fact, being raised in the Boston suburbs, no one ever even mentioned New York, let alone talked about wanting to move there. And so for the entire six weeks I assumed I would complete the course and get a job at Little, Brown, along with ten of my closest new friends who also assumed they were going to stay in Boston and work at Little, Brown, too (Little, Brown was going to have to EXPAND). But about a week before the end of the course, all my new friends decided they were moving to New York, so buckling under peer pressure, I went, too. Only I went with the assumption that I'd hate it, because that's kind of how I approach any kind of big change. I sold my car and paid for a one-month sublet on the Upper West Side. One month and I'd be back, begging the Little, Brown people for a job. I was one of the last graduates to get a job -- at Random House -- in publicity -- because I typed 103 words a minute. Because I'd taken the same typing test at almost every single publisher by that point and was really good at it. When the personnel person (aptly named "Angel" -- a man) came out and told me not to go anywhere, I thought it was because of the impressive phrase "Graduate of The Radcliffe Publishing Procedures Course, Harvard University" blazing across my resume. But of course it wasn't. It was because of the typing.

What was it like to have your book made into a film? Did you get to have a cameo and if not, why not?

Having a movie made out of my first novel was ridiculous. By which I mean, it was fantastic. How could it possibly have been a bad thing? I got paid, Ashley Judd played "me" (oops, I mean, the "fictional" character of "me"), and I got to meet, and drool over, Hugh Jackman. Twice (once on set; again on the red carpet where all I wanted to do was reach out and pet his white patent-leather trench coat). I can't tell you how many people asked me if I was "disappointed" in my movie. (I wasn't.) I also can't tell you how many people asked me how my movie "did." By which they meant, "I'm sorry your movie didn't do well." Years later, when people stopped asking me about my movie, I thought of the perfect comeback: "How did MY movie do? How did YOUR MOVIE DO?" By which I mean: "Stop looking for failure in success!" It was surreal, and heady, and I got to go out to Hollywood a few times to meet with the producer, Lynda Obst, and the screenwriter adapting the novel, for meetings in which nothing really happened! I got to attend the premiere with my entire family (and extended family) and tend to everyone's red-carpet needs except my own! (I don't know if I even remembered to wear underwear it was so fraught with wedding-type stress). And years later, I saw my DVD pictured on the back of box of Crispix as part of some free give-away with other DVDs no one had ever heard of! As for the cameo: Yes, I could have had a cameo. But: the movie started shooting less than a week after I gave birth to my (ten pound) son, and so when the producer called to invite me to appear as an extra in a party scene, I declined because, unlike celebrities these days, I hadn't lost my fifty pounds of baby weight in ten days. We did visit the set in Tribeca a few weeks later, on the day they were filming a scene in which the main line of dialogue was actually straight from the book. That line of dialogue was spoken by Hugh Jackman and if I hadn't been wearing elastic stretch pants and a maternity v-neck t-shirt I probably would have jumped him.

Where did the idea for your brilliant "annoying conversations" videos come from. And can you tell us about the Get Your Stupid Writer Feelings Hurt videos?

Thank you, first of all, for calling my "Annoying Conversations" -- the series of Xtranormal videos I've made -- brilliant. I started making them early last fall after having yet another circular conversation with my son about whether or not he'd done his homework (he did but he didn't but there wasn't any but there was some but he forget it because he didn't have any so he did it). I was also having some really annoying non-apology-apology conversations with a family member and I kind of felt like my head was exploding with all my "Am I crazy or is this conversation INCREDIBLY ANNOYING?" thoughts. I'd made an Xtranormal video the previous year -- "So You're Jewish But You Have a Christmas Tree?" -- the mother of all annoying conversations! -- and it was really fun.

Last fall I was really struggling with trying to start writing again and after I made one or two of those videos I felt something inside of me unwind. It was like I'd found a way to get back into writing without actually having to really write. Writing really short tiny little scripts almost every day was a way to trick myself into writing. It was like a little warm-up thing. And because it felt like a warm-up fun thing instead of a big real thing I didn't feel blocked. I'd tried to sit down and WRITE a few times and I wanted to die because nothing came out and it felt like such a huge set-up for failure. It felt like so much was at stake to try to write something big and long and real; writing those small little scripts for the videos was very stream-of-consciousness. With instant gratification. I'd get annoyed by something, sit down, whip out a video about it in twenty minutes, then go about my business. It felt great! Cathartic AND creatively productive! And then all of sudden people started "liking" them on Facebook and Twitter, and soon the Xtranormal people found my videos and interviewed me, and then The Huffington Post started running them and a few ended up on AOL's Homepage which was great ("Driving Under The Influence of Adele"). The one I did in the spring about making beef stew with a Cook's Illustrated recipe ended up getting retweeted by the editor of Cook's Illustrated himself!

Not to sound immodest, but I love the series of Annoying Conversations about "Getting Your Stupid Writer Feelings Hurt" because almost every single one of those conversations has happened to me and/or to writers I know. All of those videos have The Frenemy (in the Groucho Marx nose-glasses) making a writer-person ("me") feel bad about everything to do with her writing and her career. He manages to inject failure into every success. That's a huge obsession of mine, the relativity of success, especially when it comes to writing. By which I mean, you can have four published novels and a movie made from one of them and still be made to feel like -- AND make YOURSELF feel like -- a total loser. #firstworldproblems

What's your writing life like?

My writing life is really embarrassing. As I may have mentioned, I kind of stopped writing for a while after my fourth novel came out and didn't "do" so well I got discouraged. Then life interrupted (breast cancer and domestic issues). When I thought my three-years-from-hell was over, my mother got diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died in five months. Not to make her suffering about me, but it totally sucked (no other word for it) and it just took me further and further away from trying to reconnect with the creative part of myself.

For me, that "creative" part of myself got fucking smothered by all the life stress I'd experienced during most of my 40s. I ended up ghostwriting a few projects. It helped financially and it also took the pressure off writing my own stuff, since writing for someone else felt much more like a job (because it IS a job!) and less like another opportunity to stare down my writer's block. So last fall, after not having written much of anything over the past few years, I starting writing the little movie scripts. Then I wrote a piece about my mother that ran in the New York Times "Motherlode" section. And suddenly I felt that tiny little pilot light go back on.

But what really got me writing again -- I just finished an original (spec) film script and have finally started work on a collection of funny/sad memoir-ish pieces about moving back, as an adult, to where I grew up, "Still Life With Braces", was a chance online friendship with Jennifer Weiner. She'd generously mentioned my videos during an interview she gave, and when I emailed to thank her, she asked me what I was working on. She said it, like, "So what are you working on?" as if surely I was working on something! After staring at the question for a while I realized I was shocked that someone assumed I was working on something and saw me as someone who would be working on something because I'd stopped seeing myself that way. Seeing myself as a "failed" novelist and a working ghostwriter and seeing myself as "a writer" are two very different things and I'd really lost faith in myself over the years in a really big way. Jen's (yeah, I call her "Jen") belief in me has been like CPR. Without her encouragement and generosity (I'm actually using her Cape Cod beach-house-guest-house at her insistence), I don't think I'd feel able to write. Gratitude doesn't begin to express what I feel. And I know a lot of other writers who feel the same. Just ask Jillian Medoff whose recent (amazing) novel, "I Couldn't Love You More" has been touted by Jen since its publication. I know people make fun of social media but it saved my life. (NOTE FROM CAROLINE: Jennifer Weiner is undoubtably one of the kindest, funniest, most generous writers on the planet. When I was being writer bullied, she sprang to my defense. She deserves chocolate, planets, and diamonds.)

What's obsessing you now and why?

I'm obsessed with my tan feet right now. I love tan feet. And hands. I haven't had tan feet in years and my feet and hands are really tan. It's distracting me from the fact that I'm turning fifty in August. I'd been whining and bleating about turning fifty up until recently when I realized complaining about still being alive is really unseemly and in very bad taste given how many people are fighting awful diseases and terrible hardship. I think there should be a new hashtag -- much like #firstworldproblems -- #goodhealthproblems -- the kind of problems you have the luxury of complaining about because you still have your health, something none of us should ever ever take for granted. So aside from the fact that I can't fucking believe I'm going to become an AARP member, I have no complaints.

What question should I be mortified that I forgot to ask?

Hash Hags! The radio show I co-host with Ann Leary and Julie Klam! Another example of social media saving my life since I met both of them through Facebook and Twitter. It's such a fun show to do and we've had so many amazing incredible guests (mostly authors) -- you included! We''ll be on hiatus in August but back in the fall with a fantastic line-up of brilliant writer-guests whose Stupid Writer Feelings we never hurt!!

[image error]

Published on August 07, 2012 11:16

August 6, 2012

Introducing Uncaged Interviews: Meg Pokrass interviews Deborah Jiang Stein, who talks about her work with women and girls in prison, not wanting to be a therapist, and what bugs her about humans

Introducing The Uncaged Interview Series by the hilarious, smart and brilliant writer, Meg Pokrass! (That's her photo just above this block of copy.) Meg is the author of Damn Sure Right, the director of Fictionaut Five Author Interview Series, the senior associate editor of BLIP Magazine, and the associate Producer of the film From Ghost Town to Havana. Meg has advanced degrees in mischief and a curiosity the cat can only dream of having, and I'm thrilled to have her doing interviews on my blog.

Her first is on the incredible Deborah Jiang Stein, pictured at the top of this post, and the author of “Even Tough Girls Wear Tutus, ” who talks with Meg about mentors, roller-skating, pretentious people, and teaching in prisons… Thank you, Meg, and thank you Deborah for this great interview.

MP: Deborah, you are such a dynamic and creative writer... You inspire many of us, which leads me to ask you this: Have you had a mentor/mentors over the years?

DJS: Other than my own persistence, vision, hard work, and whatever innate skills, mentors continue to influence my work more than anything. As a writer I've only had one mentor and she's always chosen to remain private about this but I'm willing and open and hope I'll meet other writer/mentors.

MP: And others... life-mentors?

DJS: Beyond writing, I've been mentored since I was a little girl. An English teacher, a chemistry teacher, several business women and men, several formerly incarcerated women and men, all people who counseled, believed, hoped for and with me. Advisers like angels who expect nothing in return other than I do my best, improve myself and my work.I pass on to others whatever I learn.

MP: Can you tell us what you have done and do when you feel silent or blocked? What you use to get things going again? We all have those times...

DJS: I use my body. Move, something anything athletic - jump on my mini trampoline, jump rope, roller skate, walk, sort and organize "stuff," chew gum - I keep dozens of packs around at all times, pace, drink water, tea, chew more gum, lay on the floor and stretch. All in no specific order.

Sometimes stillness helps. Empty my mind and see if the wind blows in there. That's the hardest for me, to empty in stillness, so I work at this just for the challenge.

MP: What inspires you?

DJS: Athletes inspire me, not necessarily professionals but just any athlete who trains and trains and trains. I’m inspired by single focused discipline. And by people who’re compassionate and kind.

Children and infants in the midst of health crisis also inspire me for their capacity and will to live.

MP: Teaching in prisons must be interesting in this way, seeing life at its most confined... a world you were born inside...

DJS: In my day-to-day life, I'm inspired most of all when I'm inside prisons and look in the eyes of hundreds of women who've faced unimaginable pain and loss and still show up to hope. I'm tired of the word Hope but it's the best I have for what I see, and want to nurture, in the eyes of so many inside.

MP: Deborah, talk about an activity which you loved as a child, and which has remained with you into adulthood…

DJS: I skated as a girl and always started out on the porch then skated down our front steps bump thump as if each time would be different. But not.

My knees showed the proof, along with a pencil lead scar on one knee from an accidental poke-shallow stab, then a gray mossy scar on the other knee from falling in a cemetery. My forehead split open from a fall on granite stairs in the hospital once when I was around 5 and now the scar sits like a teeny scoop into the center of my forehead. If I'd thought ahead about careers I'd have gone to stunt school.

MP: And you skate now? Do you worry about falling?

DJS: It's like anything else, focus on what might go wrong and probably that would happen. I just think about the fun and freedom. Skating as an adult feels the same as when we were kids -- free and fun. I don't think about falling so I don't.

MP: Name 3 human qualities which bug you…

DJS: Elitism, self-importance, and pretension. They give me a sour taste in the roof of my mouth.

MP: The opposite of skating is interacting with pretensions, self-important people.

DJS: Yes. It's enough to make me want to retreat from the interwebs, where we carry on much of our daily relations. I’m part of it too, I suppose, the look-at-me syndrome, and my instinct is to pull back and get in check.

MP: You grew up with academics and creatives…

DJS: As a shy, mute, scared girl, I grew up mingling in the middle of my parents' cocktails parties of professors, artists, musicians, writers, poets (not that poets aren't writers but, you know...), painters, scientists. You get the idea.

Since I didn't talk, I observed and scanned interactions like a kiddie spy in the middle of it all. Something I can't quite pin down but I'll just say it. We're not any better than anyone else just because we're creative. Or because we’re academic or literary or awarded, or cleverish or impressed with our own impressions. We’re just not.

Maybe that's one reason I'm drawn to work in prisons. No fooling anyone there. Can't be anything but authentic.

MP: Many good artists are insecure about their work. Sensitive people carry the burden of insecurity with them, generally speaking.

DJS: I have insecurities. Lots of them. About people, most of all, and about my work, writing, talking. You name it, I've probably been insecure about it. I can get scared of myself, too. Boo!! I mean scared enough I'll get nauseous.

MP: The positive aspects of this are…

DJS: I think insecurity can drive creative power. At least, I use it that way, to do my best, to climb new heights, to accomplish what I think I can never do.

I used to have periods of muteness. I'd cry if someone looked at me. Now I work as a speaker and rooms full of people stare at me. It's not much better than when I was a kid but I refuse to let insecurity whip me to a pulp.

MP: Please talk a bit about the speaking you do in prisons with inmates and creativity.

DJS: First, it's a miracle I'm not locked up myself, considering my past.

Speaking in prisons is a little like going to a hometown for me since I was born in one. I love connecting with incarcerated women and girls because I get to offer what I’ve learned the hard way. We can talk about re-writing our stories, about loss, love, bouncing back, judgment from others, lots of other topics. I never know what we’ll discuss from prison to prison.

It goes like this. Usually I join the women in a prison gym or in the yard with as many as are permitted, hundreds, usually. After I introduce myself I go into an improv of sorts about just plain living and life skills. Since I’ve made a lifestyle change myself, I talk about what works for me and what doesn’t work, ideas to navigate the world with a “tattered” background.

Most women in prison have been abused, and also sentenced for drug related crimes. Drug addiction, alcoholism, and mental illness are now treated as criminal justice issues rather than a public health concern.

I'm a radical advocate for education as one means to help prevent incarceration. Education opens up our world. Education, drug rehab, and mental health care will reduce incarceration. I’ll do my PSA here. We have 150,000 women behind bars, most for nonviolent drug related crimes. The rate of incarceration for women has increased by 800% over the last ten years. Makes me squirm to know this.

I'm working on numbers. In total, so far I've faced thousands of women and girls across the country, and have another 100,000+ ahead of me. Even if 1% of those I meet continue with education, that's increasing the odds of more free women and girls.

Hopefully with an education, when they get out, which the majority do, their odds of substantial employment and mental wellness will go up, with more resources available.

I believe in freedom of body, mind, and spirit. Which brings me back to things like roller skating, the feeling of freedom. I love music too, because it frees the spirit, and the beach. I feel freest near water.

Added to speaking in prisons, I'm working on a program with inmate mothers who have either lost their children to foster care, or who are in the process of losing their kids. Which is many many of them. This is part of my story, so we connect on these details.

They get to see an example of positive outcome -- that's me. We more often hear the failed cases of foster care and adoption. Not that mine was easy, because it wasn't. Mothers in prison and their children swim in grief, loss, trauma, helplessness, anger, loss of power.

I'm no therapist and don't want to be, nor a legal advisor.There's power in the naming the truth. Most haven't had a trustworthy safe resource to "just be" and face their situations with something creative like writing, or improv theater. Creativity releases the spirit and mind, even behind bars, a kind of freedom.

Deborah Jiang Stein is a writer and public speaker who devotes her work to women, men, and children in the margins of society. She founded the nonprofit The unPrison Project to serve women and girls in prison and their under-age children. Author of EVEN TOUGH GIRLS WEAR TUTUS: Inside the World of a Woman Born in Prison. www.theunprisonproject.org www.deborahstein.com

[image error]

Published on August 06, 2012 12:28

Joshua Henkin talks about The World Without You, throwing out two thousand pages (yes, that's right), and so much more

Joshua Henkin doesn't just write novels. He creates worlds. His characters are so alive, they breathe on the page, and you swear if you walk a block, you'll run into one of the places he writes about. He's the author of Matrimony (A New York Times Notable book), Swimming Across the Hudson (A Los Angeles Times Notable book), and most recently The World Without You, an Indie Next Pick that is racking up so many raves, he can paper a villa with them. (I raved about it for the Boston Globe.) I'm honored to have him here to talk about writing and his extraordinary novel. Thank you, Joshua!

You have this absolutely mastery with creating characters who are rich and multi-faceted. So let's talk process. How do you craft your characters? And do you find that being able to see into the lives of people on the page translates so you can also better understand people in the flesh?

It’s a mystery to me how the book comes into being (fiction writing is such an intuitive process), which may be why I always wonder whether I’ll ever be able to do it again; the fraud police is always hanging over you. But for me fiction is first and foremost about character—about making my readers come to know my characters as well as they know the people in their own lives. And I think the way you craft characters is that you live with them day in and day out and you ask yourself as many questions as you can about them. Who is your character? Where did she grow up? What kind of work does she do? Does she like spinach? Does she sleep on her back, her stomach, or her side? It may seem inconsequential to know (much less describe) how a character sleeps, but not if the gesture is laden with meaning, as all gestures in fiction should be. Does the character who sleeps on her side do so because she doesn’t like the smell of her husband’s breath? Does she do so because she hears better out of one ear than the other and if she sleeps on her good ear she won’t be able to hear when her child cries out at night?

In my Matrimony, Julian meets his eventual-wife Mia after having spotted her in their college facebook. He dubs her Mia from Montreal. I wrote that phrase instinctively, probably because my own girlfriend freshman year of college was named Laura, and my roommate called her Laura from Larchmont. I liked the alliterative sound of those words. Before I wrote Mia from Montreal, I had no idea where Mia came from. But she had to come from somewhere, and Montreal seemed as good a place as any. But then I had to own up to what I’d written. How did Mia’s family get to Montreal? Had they lived there for centuries? Were they expatriates, and if so, from where? And how did Mia end up back in the States, in western Massachusetts, for college? I could have chosen Mia from Madagascar or Mia from Maryland, and if I’d chosen Mia from Maryland, there might have been, for all I know, a long section in Matrimony about her family’s tangled relationship with the clamming industry. But she wasn’t Mia from Maryland, she was Mia from Montreal, and so I discovered that her father had gone to teach physics at McGill, forcing her mother to abandon her career in the process, and that Mia, out of loyalty to her mother, decided to retrace her mother’s steps back to Massachusetts. I knew none of this until I wrote the words Mia from Montreal, just as the writer who has a character who sleeps on her side doesn’t know why she sleeps on her side until she does so.

Does being able to see into the lives of people on the page translate into being better able to understand people in the flesh?

Maybe. I’d like to think that writing fiction gives you a greater capacity for empathy. But my suspicion is that the cause and effect is in reverse—that understanding people better in the flesh leads you to be able to do it on the page.

Your subject seems to be family. So what was yours like? Do you draw on it at all?

Ron Carlson said that he writes from personal experiences whether or not he had them. I feel the same way. Good fiction has to be emotionally autobiographical. The writer has to be at risk; you have to be very close to your material. That’s quite a different thing, however, from saying that the work is narrowly autobiographical or that your characters are based on people you know. I come from a complicated family in that, though both my parents were Jewish and raised in New York City, their backgrounds couldn’t have been more different. My paternal grandfather was a famous Orthodox rabbi who lived on the Lower East Side for fifty years and never learned English. He lived exclusively in a Yiddish-speaking world. My mother was raised in the Bronx, on the Grand Concourse, in a secular Jewish home. She went to a progressive private school with no walls between the classrooms and everyone campaigned for Adlai Stevenson and believed that someday we’d be speaking Esperanto. So I know a lot about both the religious Jewish world and the secular Jewish world, and absolutely—my knowledge of those worlds helped in writing The World Without You.

You also teach as well as write--as I do--and I wanted your take on what you get from your students and when you feel that you absolutely must take a break and do nothing but write. Or does that never happen for you?

I direct Brooklyn College’s Fiction MFA Program, and at the risk of sounding like a pollyana, I can’t imagine a better job. In a typical year at Brooklyn we get 500 MFA fiction applicants for fifteen spots in our incoming class. So we’re dealing with some of the very best young writers out there. In the last few months alone, five of our recent graduates have gotten book contracts. There are writers who wouldn’t know how to teach; for them, writing is an intuitive process and they aren’t fully conscious of what they’re doing. For me, it was the opposite. I could read someone else’s short story and figure out what wasn’t working long before I could make things work in my own stories. I needed to learn how to become a more intuitive writer, and critiquing other people’s stories helped me do that; it still helps me. I’ve been at this process longer than my students have, but we’re all struggling with the same thing—how to write convincing stories; how to make our characters come so deeply to life they feel as real as, even realer than, the actual people in our own lives; how to use language in a way that’s precise and beautiful and utterly true. That never changes. So in a way, even though I’m the instructor, we’re all students in the room. Also, I’m a fairly social person, and writing is incredibly solitary, so teaching gives me the chance to be with other people and to talk about what I love.

Obviously, teaching takes time away from my writing, but a lot of things take time away from my writing—my wife, my kids, my friends, going out to dinner, going to the movies—and I wouldn’t trade those things for anything in the world. So you manage to find a balance. I write from 9 in the morning until noon five days a week during the semester, and then over school vacations I write more. Do I wish there were more hours in the day? Sure. But on balance, I’m able to find time to write.

Why do you think your novel seems to have touched a nerve? Besides the quality of the writing, what is it about this multi-faceted family that has won over so many critics and readers, do you think?

That’s hard for me to say. I’m just grateful for the response. Why something works is as mysterious to the writer as it is to anyone else.

What's obsessing you now and why?

My new novel, which is still in its very early incubating stages. I’d been hoping to be further along with it at this point, but it’s still taking shape in my mind. Not that I ever know in advance what my book is going to be about, but I like to have some general idea of what’s animating it, and that animation is still coming to me—coming more slowly than I would like.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

How many pages I threw out. Two thousand for The World Without You and three thousand for Matrimony. I can’t even remember for Swimming Across the Hudson, but a lot there too. Maybe I’ll be down to one thousand for my next book, but I hope not. You have to write a lot of bad pages to get to the good pages. I remind my students every day how much hard work it takes to get a novel right. Talent is important, of course, but persistence and determination are at least as important.> > Thank you, thank you![image error]

Published on August 06, 2012 12:09

August 4, 2012

Jennifer Haigh talks about The Boy Vanishes, her new short story on Byliner

Jennifer Haigh is known for her luminous four novels: The Three Mrs. Kimbles, which won the 2004 PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction, Baker Towers, a New York Times bestseller and a PEN/L.L. Winship Award winner, Faith, and The Condition. But she now has an extraordinary short story, The Boy Vanishes, up at Byliner.com, which specializes in digital fiction shorts meant to be read in one sitting. I'm honored to have Jennifer here. Thanks, Jennifer!

I went to the Byliner site and was knocked over. Fantastic writers, great stories, and lots of extra features, too. How is it a different experience for you, writing a short story, rather than a novel? Do you prefer one form over the other?

Stories are my first love. I wrote them for many years before I even attempted a novel. I prefer whichever I’m not writing at the moment. If I’m writing a story, I wish it were a novel. When I’m deep in a novel, a short story seems like a little slice of heaven.

Because the times have so much to do with how people act and react, can you talk about why you set the story in 1976 around the Bicentennial?

In the 1970s there were no Amber Alerts. Society was much less aware of potential threats against children, and it informed the way kids and parents were expected to behave. Tim O’Connor and his friends have much more autonomy than most teenagers have today. If this story were set in 2012, every single character – kids, parents, teachers, cops – would behave differently.

So much of your story is about how we live with the spaces in our lives, how we grapple with guilt. There are other tragedies in the town: an unplanned, a heroin overdose, a teacher is caught with a student--but all spin out from the vanishing and all are somehow connected, which creates a gripping portrait of a community at odds with itself. Can you comment on this?

When I’m writing a story – regardless of its length – I try to think about causality rather than plot. Fiction works best when it unfolds the way life does, one event leading to another, characters reacting to each other in a constant feedback loop, whether they realize it or not.

Can you tell me what’s obsessing you now and why?

I’ve been working on the screen adaptation of my novel FAITH. It’s a marvelously useful exercise for a novelist. As a writer, I have always been preoccupied with questions of dramatic structure. Writing a screenplay is like building an entirely different container to pour the story into.What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

How about: E-publishing a short story is a fairly new phenomenon for a writer. How is the experience different from publishing in a magazine or literary journal?So far it’s been a fascinating experiment. I love the immediacy of publishing this way. Readers can buy, download, read and react to the story in a matter of minutes, not weeks or months. On the other hand, I’m aware

Published on August 04, 2012 11:34

August 3, 2012

The Is It Tomorrow book tour starts here..with Old Gringo boots

So is it wrong to want to marry a pair of boots? I first heard about Old Gringo artisan boots from writers Jo-Ann Mapson and Carolyn Turgeon. "They fit like slippers," Carolyn insisted.

"You'll never take them off, " Jo-ann told me.

For my tour for Pictures of You, I wanted a talisman. Something to make me feel powerful and confidant and unique. Also, because I was wearing two different slinky black dresses all the time, I needed to stand out. So I got on ebay and found a pair of red cowboy boots and suddenly, the Red Cowboy Boot and Vintage Beaded Cardigan Tour was born! And those red boots? They made me feel powerful. They made me feel like I could conquer the world. And they began to get their own fans. When I was video-taped being interviewed with the amazing Anne Lamott as part of Algonquin Books Bookclub series, one of the first questions someone asked was, "Tell us about the red cowboy boots."

Now, I still love those red boots, but I wanted to step things up a bit. I fell wildly, truly, madly, deeply, passionately in love with these boots. I loved the whole Old Gringo story, the care they take with their boots, the way these boots are really like nothing you have ever seen or felt before.

So, Is It Tomorrow is coming out in May, 2013. And I hope you'll come out for my Old Gringo boots and Isadora Duncan Long Scarf tour.

P.S. I still don't have any new dresses.

Published on August 03, 2012 13:53

August 2, 2012

Ann Bauer talks about The Forever Marriage, uncertainty, logic and the idea or marriage

I get a lot of suggestions from friends, or other critics and editors about what I should read next. I always take the suggestions because there's nothing more thrilling than a wonderful read. Ann Bauer's The Forever Marriage was suggested to me and it's a knockout. What I so deeply admire is that Bauer takes Carmen, a character who is by no means perfect--She's prickly. She's not altogether honest with herself and others--and slowly reveals her transformation as she begins to explore what she thought was her loveless marriage. The Forever Marriage was named one of the Best Books of the Week by PW, and boy, is it ever.

Thanks so much, Ann for letting me pester you with questions!

What I loved so much about The Forever Marriage is the character of Carmen. At first, I didn’t know how I felt about her because she was so prickly, so relieved about her husband’s death. But then, as she begins to look at their shared pasts, and her own choices in life, she begins to transform and take new responsibility for what her marriage was like. And as she transforms, so does they way she sees their shared past. And I fell in love with her. Was it difficult writing the earlier Carmen when she wasn’t so instantly sympathetic? What were the challenges for you?

I started this book in 2007 because I had a very close friend who was facing Carmen’s dilemma: She had a husband she never really loved who’d been slowly dying of cancer for 9 years. The truth is, I was struggling with my friend’s situation. I was watching this woman I adored become frustrated and bitter because her husband just kept hanging on. It was so uncomfortable. I sympathized with her but I was also really horrified that a marriage could turn so empty. That a man could die with his wife at his side, rooting for him to go.

So I already loved Carmen despite all her sharp edges. The biggest hurdle for me was the actual death of the husband so I started there. I think I was faking myself out, trying to get through the worst of it and imagine what had not yet happened (my friend’s husband would actually live for another three years). I needed to get through that scene in order to work through the rest of the story. But it means that readers meet Carmen when she’s behaving pretty unforgivably, when she’s the least likable. Then my job, as the writer, was to make people see who Carmen really is and come to understand her and fall in love with her over the course of the book.

Without giving away too much, I think my biggest challenge was her husband, Jobe. He’s based in part on my own very sweet husband—this quiet, brilliant mathematician. So I kept wanting to make him perfect but, of course, he couldn’t be. No interesting character is... It was really deep into the writing of this novel that I finally “found” Jobe’s weaknesses and flaws and that’s what I think makes his character more believable, while also redeeming Carmen. You see that their relationship wasn’t black and white. She wasn’t the only one in the marriage who made mistakes.

In the book, Carmen isn’t just battling the end of her marriage, she’s battling breast cancer, which puts everything into sharper focus--her past and her future. Her body, in a way, influences her mind. Can you talk a bit about this?

This novel is all about uncertainty. It’s about that point you reach (usually in your early 40s….at least that’s when it happened to me) when you look back and say, “What was I thinking when I made those decisions? I calculated so poorly. Nothing turned out the way I thought.” I knew that was going to happen to Carmen in a big way and the breast cancer was this stopping force. She thought she would have a blissful independent life after Jobe died and suddenly she found herself ill and scared and strangely unhappy to be alone.

Even before she’s diagnosed with cancer, Carmen has odd moments of missing this man she’s been wishing dead. So her mind is betraying her, getting in the way of her imagined freedom. Then her body betrays her, too, and everything she took for granted—her looks, her sexuality, her good health—becomes tenuous. This is what it takes for Carmen to examine herself and her choices honestly.

And in some sense, the cancer gives her a way to forgive herself. Because as tough as readers are on Carmen, she’s even tougher on herself. When she goes through treatment, she’s humbled by the experience. At one point she even thinks of chemotherapy as penance. The situation means her relationships become more defined—with her mother-in-law, Olive; her lover, Danny; and her best friend, Jana—and through these people, Carmen realizes some really hard clear truths about her marriage to Jobe.

The novel is so intricately plotted, with so many unexpected swerves in the road, that it moves to a resolution I never really saw coming. Which brings me to one of my obsessive questions. Do you plot this all out in advance--as much as you can? Do you know where you’re going in a novel, or do you simply see what happens and follow that?

Oh, this is such an excellent question! Because I’m obsessed with it, too. The answer is no. I don’t plot anything out in advance. I start writing at the beginning and I plow through straight toward the end. Only I don’t know where the end is and in the case of this book I was completely taken by surprise.

It’s odd, because I’m a kind of logical person. I’m a list Now I should say, this method of writing leads to some wrong turns. I remember at one point sending pages to my agent and he wrote back about a really dramatic plot point and said “Ann this is too much. Please rethink.” So I did and of course he was right. I’d thrown in something wild because I didn’t know where the story was going; so I ripped that out and started over.

Good readers are critical—I’m really lucky that I have two: my agent, Esmond, and a writer I’ve known for a dozen years. But they’re particularly important if you’re not following an outline because you can so easily go off in some crazy direction. The secret is to write organically but also slowly and carefully enough that you unearth a whole, cohesive story. It’s painstaking but soooo satisfying when it works.

Is there such a thing as a forever marriage? And what do you think that really means, for both Carmen and for anyone in a relationship? What’s obsessing you now and why?

Caroline, I think that’s what my whole book was about. I mean, it’s about regret and wanting what you can’t have and forgiving yourself for things you can’t change…But it’s also about that whole ideal of a marriage, the union that both transcends and sort of “roots” you to the world. That’s what I craved for Carmen and Jobe and spent a whole novel trying to help her find. It’s also what I crave for myself.

I’ve been divorced…and I am my sweet, lovely husband’s third wife, so it’s clear to me that not every marriage is forever. Sometimes, to be honest, I feel like a bit of a fraud. Because I have no idea how to stay married! What I do know is this: I’m a nicer, saner, calmer person with this man and he’s a warmer, more adventuresome, more joyful person with me. Beyond that, I know that neither of us is perfect. I’ve seen his flaws and, God help me, he’s seen plenty of mine. I can be really sharp and mean, just like Carmen. But there’s something real and quiet that makes me think, “Oooh, this feels real, like it was meant to be.” It’s a little like that rightness you get when a story works.

Yes, I really do think there’s such a thing as a forever marriage. And though I’m not sure what I believe about God and heaven, I think a really wonderful connected marriage might not stop with death.

As a writer (please forgive me) I can’t say what’s obsessing me right now. There are two paradoxical things consuming me—one a bizarre historical event and the other a religious doctrine—but I need some quiet time to figure out what they have to do with each other.

Before writing The Forever Marriage, I worked for two years on a book that I discussed with too many people. The novel had other problems, too—it just never came together—so eventually I put it aside. But I learned a huge amount during those couple of years, about how to conceive and plot a novel. So when I was writing this book, I spoke to no one about it except my agent, my reader and the friend on whom Carmen was based.

Personally, though, I can tell you exactly what I’m obsessing about. My youngest child leaves for college in 11 days. I had my first baby at 21, so this will be my first-ever adult experience of living without a child in my home. Frankly, I’m terrified. Also curious as to what I will do….

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

The question no one has asked is, what is the significance of the math in the novel? Why was Bernhard Riemann’s story so important? And my answer would be that I think mathematicians and physicists are really wrestling with the fundamental questions. Why are we here? What’s our purpose? How does this universe—our planet, human life—make sense? I was particularly interested in the concept of time and whether it really exists. If time is a fiction (as Einstein said) then Carmen could still go back and fix things with Jobe, maybe even fall in love with him…I wanted to create a world in which the past could be accessed and the future contained literally infinite possibilities. There is something so hopeful to me about the premise of infinity: If the numbers never stop, we have an unassailable model for “Forever.” So in Jobe’s mathematical sphere, there is no end and love is never done.

Published on August 02, 2012 08:15

Win a copy of Ilie Ruby's The Salt God's Daughter

Every once in a while, like a surprise, I get an email from an author I don't know. Sometimes an author will write because he or she likes my work. (Oh joy! Oh bliss!) Sometimes authors write because they want me to like theirs. (Joy and bliss again--what's better than discovering an author?) Either way, it all builds this incredible sense of community that I love. A few months ago I heard from Ilie Ruby. She had a new novel out--would I consider blurbing it? I actually already had her novel, The Salt God's Daughter, on my to-be-reviewed shelf, but her message made me take it out again, because how could I not start to read it immediately after she had taken the time to write me?

I fell in love by page 3.

The Salt God's Daughter isn't just gorgeously written (it's a stunner), the story is eerie, unsettling and mythical, about three generations of women who all share something exceptional.

And to celebrate this amazing book, there's a giveaway! The first person to comment on Ilie's post below gets an inscribed copy of The Salt God's Daughter! (Be sure to email me your address so you can get the book! carleavitt@hotmail.com). Trust me, you will love, love, love this novel.

Thank you, Ilie, for this post!

I've always been drawn to the exotic qualities of real life, to what's beautiful about the ordinary and what's mythic about the human struggle.

My mother was a folksinger and painter, and the legend of the selkie (or “silkie”), which influenced the structure of this book, came to me as a song she used to play on the guitar—The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry. There are many versions of selkie mythology, tales of shape-shifting creatures that are seals in the water and are people on land. The version I grew up with chronicles the journey of a woman searching for love who draws to her a man from the sea, and gives birth to a child that is unlike others. What made this folktale a natural vessel for the novel was its patriarchal patterning, set within a time when women are glorified and demonized for their sexuality.

This story takes place in Long Beach, CA, a beautiful and Disney-esque place where huge oil derricks rise out of the ocean on man-made islands, covered in faux apartment-like casings with teal embellishments. The drilling is obscured by rainbow-lit waterfalls that drown out the noise. I find it fascinating—the effort of hidden things, and thought it would be interesting to set the story in the 70s and 80s (the era in which I grew up), in the riptide of feminism (circa General Hospital's 1981 wedding of Luke and Laura). At its core, the story illuminates the universal search and deep longing for love, and its torrential and hidden effects on our course at different times in our lives. It was fascinating to explore this through the eyes of my main character, Ruthie, an ordinary girl who evolves beyond the limits of family origin and culture. I wanted not to create a version of a feminist superhero we so often see in the media—portrayed as a martial arts expert or a sexualized gunslinger—rather, Ruthie is extraordinary in her ability to apprehend tragedy, and to transcend all that is hidden about her own identity—as a daughter, mother, as a lover, and ultimately as a human being. Ruthie is, in fact, that girl—the one nobody thought would make it, but who does.

Whenever I think of her, I'm reminded of the image of the tree pushing up through the concrete in A Tree Grows In Brooklyn, one of my favorite novels of all time. I hope readers will embrace Ruthie, and her daughter Naida, and enjoy this story, captured in a place where gritty human truths spark discoveries and epiphanies that seem divine.

Published on August 02, 2012 08:00

July 29, 2012

Christie Nelson talks about how all art and lots of play make for a dazzling writer

Can learning book-binding help you become a better writer? Christie Nelson thinks so. Her second novel, Dreaming Mill Valley will be out soon, and she went back to camp to see what it was like to craft a hand-made book in a wooded forest, "eating at the chow palace, swimming in the chilly river, and sleeping in a rustic tent. I asked her to write something about it. Thanks so much, Christie!

Breaking The Mold

What’s a writer doing at Art Camp? I pondered that question as we traveled up the Sierra Nevada Mountains, crossed Quincy’s wide meadows, and bumped along the dusty road leading into Feather River Art Camp. My head had been down for so long pushing toward the finish line of a novel that art camp sounded impossibly crazy. “Think of it,” a friend persisted. “This is a camp for everybody to make art. It’s a rare opportunity to be drawn into the creative process without any distractions or mundane interferences. It’s you, camp, and your art.” But my art is writing, I thought, not the visual arts. Then I saw the offering of Bookmaking, and my objections evaporated. Rhiannon Alpers, a book artist and letterpress printer at San Francisco Center for the Book was teaching the workshop. How would it feel to make a real book with my hands compared to the long haul of novel writing? The lure was tantalizing. I could write in the afternoons; I wouldn’t break rhythm. Like a guilty wife taking a lover, I signed on. My first glimpse of camp in a wood dotted with old-timey buildings, reminded me of childhood, and I quickly saw that most of the workshops were held outdoors. The scene resembled a Sherwood Forest of artists, setting up tables and stringing lights in the branches. The afternoon sun filtered through the trees, Spanish Creek called to swimmers, and the wind sent the pines to singing. When the dinner bell rang, off we trooped to the Chow Palace. That night the temperature dipped to 37 degrees, and we slept in our rustic cabin like babes under down comforters. On the first morning, Rhiannon, a tall, striking redhead with a soft voice, took control of our group of eight. We arrived with basic supplies; she brought paper, thread, wood, needles, leather scraps and paint. Clumsy at first, I fell under the spell of completing one task at a time: measuring, cutting, folding, painting and sewing. I soon realized that the craft of bookmaking is a blend of geometry and artistic vision. Rhiannon’s direction was precise, her artistry astonishing.In the hot afternoon on the shaded porch of my cabin, I wrote. Playfulness entered my writing. I took more risks, dove deeper. Somehow giving myself permission to learn a new craft energized my writing practice and fortified my dedication. By week’s end, I made two books that I loved. No matter that the pages were blank—they were smooth and creamy, scored and folded by my fingers; the wood cover didn’t have a title—it was sanded and painted, embellished with a driftwood handle that I had found on a beach in Baja; the binding had no glue—it was hand-stitched in bright orange thread in an intricate Copic stitch pattern. Now, following an invitation from Rhiannon to publish a small letterpress edition at San Francisco Center for the Book, my memoir, My Moveable Feast, with drawings by Fiona Taylor, is launching on September 7th. And that novel I was writing? Dreaming Mill Valley, will be published this October in print and e-book formats. My friend was right. Fostered in art camp, my creativity knew no borders. It flowed freely, summoning the Muse, urging me on. www.christienelson.comwww.featherriverartcamp.comwww.sfcb.orgwww.rhiannonalpers.com

Published on July 29, 2012 21:53

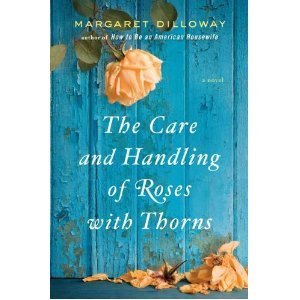

Margaret Dilloway talks about The Care and Handling of Roses with Thorns, outlining, samurai women, and so much more

See the photo above this text? That's Margaret Dilloway clowning it up at the Pulpwood Queens Girlfriend Weekend (yes, I'm afraid that is me in the clown dress and pigtails and red boots in front, standing by author Victoria Zackheim and Wade Rouse!) Her first novel How To Be An American Housewife, was stellar, and her latest novel, The Care and Handling of Roses with Thorns is even better. About the cost of love, roses, and kidney disease, it's that terrific hybrid--gloriously literary and also a page-turner. I'm thrilled to have Margaret here--and I hope she doesn't mind the clown pictures.

I adored the heroine of your new novel. She really starts off so prickly, and then gradually, she begins to unfold, much like a flower, and I ended up being totally in love with her. Where'd she come from?

I had the idea to write a book about rose breeding, so I began research. When I found out that many rose breeding hobbyists are retired scientists or engineers, the voice of Gal popped into my head. She always thinks she’s correct, she loves order, and she has a very methodical way of doing things. But, she’s extremely passionate and wants what’s best for everyone. She’s partially based on my late sister-in-law, whose lifelong struggle with kidney failureended last Christmas. I think Gal has developed a take-no-prisoners attitude toward life because that very attitude is necessary for surviving her chronic illness.

The details, both about roses and kidney dialysis, were fascinating. Can you tell me about the research process? What surprised you?

For rose breeding, what surprised me most was the amount of chance involved. So much of it depends on luck. The breeder who helped me most, Jim Sproul, breeds many Hulthemia roses. He told me his child got a perfect specimen on the first try. Jim was the first one to get Hulthemias to the consumer market this year—they’re called the Eyeconic Lemonade and Pink Lemonade.

For the dialysis/kidney stuff, the biggest surprise came with how many times medical doctors sort of mess up because sometimes they’re too full of pride to listen to the patient. The medical stories in Roses came from my sister-in-law. She really did have a doctor who told her that her allergy to intravenous pyelogram (IVP) dye was psychosomatic and who would not let her proceed to the transplant list unless she got this specific kind of screener using this dye. Finally, desperate to be on the transplant list, she agreed, and she had a severe anaphalytic reaction. She later switched doctors, and her new doctor pointed to studies showing it was not psychosomatic; the other doctor had clung to old beliefs and ignored her concerns.

Tell us about your writing process. Do you map things out? Rewrite a million times?

I write an outline. I actually really hate making an outline, but it helps me. Then I more or less follow it, but I veer off quite a bit. For Roses, the finished plot only vaguely resembles the original outline, and the ending’s totally different. Luckily, my editor was fine with that—she’d signed off on the original outline, but she loved how it turned out.

What's obsessing you now?

Samurai! I’m writing a book about a samurai woman who, if she were indeed a real person, might have been in my family tree. Tomoe Gozen. She lived during 12th century Japan, before the really popular time of samurai, so there are lots of persnickety details I am trying to get right. For example, they used a different kind of sword in 12th century Japan than in 15th century, and green tea was only drunk by monks and royalty then.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

People say that Roses is very different than your first book, How to Be an American Housewife. How did that happen?

To me, they don’t seem too different, because I wrote both of them. First, they are both stories about female familial relationships. They have strong, potentially unlikeable, female characters who are a bit different than the typical heroine.

One of the recurring themes in my work is, how do you manage to find happiness when so much in your life can, and will, go wrong? I write imperfect characters struggling to find hope, beauty, and love in their common, everyday lives.

Published on July 29, 2012 21:45