Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 100

January 5, 2013

Edward Champion talks about his new show Follow Your Ears, giving up the Bat Segundo Show, his video on Gary Shteyngart, frozen peas, and so much more

Edward Champion is hilarious, smart, opinionated and game-changing. After many years, he's given up the outrageously funny Bat Segundo Show, he's the managing editor of the fabulous cultural blog Reluctant Habits, and he's now onto something new, something more thematic, Follow Your Ears, which he'll talk about in the very next question. I'm thrilled to have him here. Thanks, thanks, thanks, Edward! (See? I didn't call you Bat.)

Tell us about your new show, Follow Your Ears.

I believed I was largely done with radio: not necessarily in some mid-career vocational goosestep of mock desperation akin to John Malkovich taking up as puppeteer, but I certainly knew that I had to evolve if I wanted to continue in this medium without becoming one of those dessicated husks phoning it in. Then Sandy Hook happened. And I watched in real time as professed journalists got the Lanza brothers mixed up and spread misinformation with the kind of recklessness one associates with giving matches and lighter fluid to an arsonist. My conscience snapped. It was clear that we had to talk about guns. So I began finding authors who had written books about guns and contacting publicists. The idea then was some Bat Segundo one-off. But then I started getting more ideas. And I'm interviewing people again. But I'm being more journalistic with this program. The new style seems to be pushing me somewhere new. Yesterday, a legendary filmmaker called me a "rough interviewer." But I also had a difficult conversation a few days ago that put me in tears. I'm trying to take more risks and put myself into more emotional territory. But the hope here is to unite numerous viewpoints around a theme (in this case, guns) and have the listener follow along with her ears along. I'm hoping that Follow Your Ears will spark conversations and dialogues, and that I can weave some of the results back into future shows. For now I'm committed to a first season of eight to ten episodes. And I'll see where that takes me.

Was it hard to give up Bat Segundo?

There's always a tinge of wistfulness when you end any project, but the impulse to end Bat Segundo was a long time in arriving. 500 always struck me as a nice round number to end the program. I felt that I had explored just about every angle I could with that format and I wanted to go out with my best work. You don't want to soldier on and turn into a robot. While Segundo was a joy to the very end, the time had come to move on. I suspect you may share this problem, Caroline, but I'm the type who gets into a good deal of trouble if I don't have a few massive projects I'm working on. And I suspect this is another reason why Follow Your Ears happened: a bulwark against my worst instincts! But I also feel that you should rethink what you do every few years. Because change is a constant and, if you don't understand that, you'll be extirpating some very exciting possibilities from your life.

I adored the video you did on Gary Shteyngart and blurbing. (Gary, by the way, already gave me a blurb for a book I haven't written yet: Caroline leavitt's unwritten book is the best Caroline Leavitt unwritten book of 2013.) Can you talk about the video, please?

Thanks for digging the video. Glad to hear that Gary used his blurb kung-fu for encouraging purposes. I had a blast making the documentary and I'm still highly amused that I have a thick three inch binder filled with tons of paperwork labeled SHTEYNGART. Nobody was more surprised than me that so many people signed on for it. It all started off as a silly thought I had before going to a party. "There's a Tumblr. There's a reading event. Maybe there should be a documentary." Now I'm the kind of guy who acts on his ideas. So I sent some emails before going to the party. Hours later, the inbox was filling with yeses. And it was really a matter of sorting out logistics and trying many new things, such as going to DC on a whim after Ron Charles graciously agreed to appear in it.

We're now at a very exciting historical moment -- perhaps on par with the first cinema verite filmmakers going out into the world with 16mm equipment -- where digital tools enable us to capture moments of life. On the other hand, it's becoming increasingly difficult to get audiences to sit down for a fifteen minute documentary (and yet ironically they will listen to podcasts over an hour, thanks in large part to commuting). I realized that I had to earn those fifteen minutes of attention. So I did my best to keep things lively -- interviewing people in silly locations, shooting that bowling montage, keeping up the pace. I couldn't get everything in. There's some funny material of John Wray juggling that I had to sadly abandon. But I did learn that I could cut in my own distinctive way while simultaneously respecting audiences in 2013. What's especially weird about the Shteyngart doc is that it's informed some of the direction for Follow Your Ears, and vice versa. I definitely plan on doing another one. But it has to be a subject that I can get consumed by and that audiences are also willing to get caught up in. I should also point out, in hindsight, that I had no idea that blurbing would be this interesting!

What's obsessing you now?

I haven't abandoned the Modern Library Reading Challenge, although I'm at a very time-consuming spot. FINNEGANS WAKE. I've been reading books written by Joyce, books written about Joyce, and doing this along with my other ten billion pursuits.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Why did you leave out the frozen peas? Did somebody hit you in the head?

Published on January 05, 2013 09:18

January 3, 2013

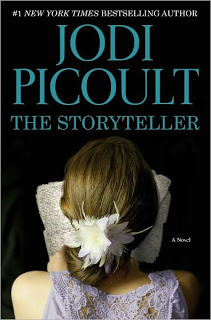

Jodi Picoult talks about The Storyteller, the Holocaust, moral choices, cinnamon chocolate rolls, and so much more

Jodi Picoult is known for talking big themes and thorny moral issues and turning them into riveting art. She's the number 1 NYT bestselling author of 18 novels, and her new novel, The Storyteller, about the Holocaust and the stories we tell to ourselves and others, was so haunting, that I started it in the afternoon, during Christmas, and didn't stop reading until the middle of the night. And then, of course, I couldn't sleep because I was still in the world of her story. But Jodi is something more that just a dazzling author--she's got a heart the size of Jupiter, she's hilariously funny, and of course, she has the best curls around. I'm thrilled to have Jodi here again (my blog is always your blog, Jodi.) Thank you, thank you, thank you.

The stories of the Holocaust here are so vivid and unsettling and disturbing--I’m wondering about how difficult this was to write, if there was ever a moment, when you had to stop and take a breath. As a reader, I was torn between wanting to stop because it was so horrific and desperately needing to keep reading to find out what was going to happen next. (I never stopped.)

It was more difficult emotionally to research than to write. I met with multiple Holocaust survivors, some of whom really couldn't even speak to me without their entire demeanor changing as their own words took them back. One survivor, with whom I've become friendly, reminded me so much of my own grandmother that it wrecked me to hear what she had been through. If I have done justice to the experience of being a prisoner in a camp, it is due to the fact that I really internalized the stories these men and women told me, and just squeezed back all the pain onto the page. By the time I got to writing the book, though, I was driven -- I so badly wanted to honor their experiences, because they'd trusted me with them. Difficult but in a different way was creating a Nazi narrative. Obviously it's pretty impossible to find a former Nazi willing to chat about his experiences...so instead I had to rely on witness testimony from the Nuremberg Trials, transcripts of Nazis who have been captured by the Dept. of Justice, and the remarkable historical acumen of Peter Black, a senior historian at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. I could study this stuff my whole life and still not understand the rank and file structure of the Nazi army.

The Storyteller is so much about the power of stories--and what I especially loved is that, structurally, it’s set up that way, story within story. Minka’s story spans most of the novel, but then there is also the story that Minka is writing, and the story that Josef tells us. I like to say that stories save our souls. Would you comment on that?

I think Minka would agree, and certainly Sage by the end of the book. There are all kinds of stories we tell to save ourselves -- either literally or figuratively. One of the things I love is that Minka's story isn't a light and breezy fairytale. It's dark and dangerous and gothic. I think the story she chooses to tell accurately reflects the world coming to pieces around her. And really, isn't that all novelists do? Our books are a mirror for our own thoughts, and for the hairline cracks we see in the world.

The book is also about the secrets we keep to protect ourselves, to protect others, and then fiction becomes the way to remind ourselves that we are not alone, that there is a family of man. “Fiction is contagious,” one character says. I often sign my books saying, “stories save our lives,” and they do here. Can you talk a bit about that?

Obviously, in the case of Minka, her story keeps her alive as Scheherezade's did. The reason a Nazi officer protects her from a more devastating experience at Auschwitz is because he is captured by her words, which he sees as an allegory for his own life. I do believe that fiction is an equation - the reader brings half of the final sum to the table; the writer can't do it alone. That's why different people have different experiences reading the same book, and focus on different characters or passages that resonate individually. Had a different officer been the one to find Minka's fragmented story, she might have been killed immediately - yet this man sees it as a mythological study of himself and his own brother...a truth that he could never utter aloud, because it would lead to his own punishment. It is the opportunity for "what if," for an ending other than the one assumed to be inevitable - that keeps this particular officer reading, and that ultimately is Minka's salvation. The Nazi cannot imagine a future other than the hell he is living; Minka CAN imagine, and that's the one power she holds over him.

I never saw the ending coming. Did you? Or did it surprise you as well in the writing?

Oh, I always know the ending before I write. I knew the big twist right off the bat. There was, however, a smaller psychological twist that I can't give away that revealed itself to me near the end as I was typing and it was so PERFECT I could not believe I hadn't known it was coming!

The Storyteller asks how can we--and should we--forgive the unforgivable, and it comes up with the answer that we can’t forgive, but we can hold accountable, that when we forgive we do it for ourselves, not for the other person, which seems to me the right response. Can you comment on that, please?

Well, of course, Simon Wiesenthal is really the one you should be asking! It was his incredible personal story, THE SUNFLOWER, that led me to write this book. In his account, he tells of being a concentration camp prisoner and being summoned to the bed of a dying Nazi, who wants a Jew to whom he can confess...and who will in turn offer him forgiveness. The great irony of course is that any Jew will do to this man, that they are all interchangeable, which is exactly the sort of thinking that made the Holocaust possible and is also exactly the reason you know he hasn't evolved mentally in any way. But beyond that, Judaism holds that the only people with the capacity to forgive are the ones to whom the wrong was done, and they were dead. The Wiesenthal book has spurred much philosophical debate about forgiveness and repentence and I'm hardly as qualified to comment as Rabbi Kushner or Archbishop Tutu. However, I asked every Holocaust survivor I spoke with if they could forgive the Nazis. Some said they couldn't. Some said they could, but would not forget. The ones who DID say they could forgive said it was not because they were erasing the grievous harm done to Jews, but because to not forgive meant the perpetrators of genocide still held some sway over them, able to make them bitter or keep them trapped in the past. The ultimate coda to the Holocaust is not just that Jews continue to live and thrive, but that these same Jews who were once prisoners now have the ultimate power: to let go and move on.

In your acknowledgements you talk about honoring those who survived and those who didn't. Can you talk a bit about the perils and triumphs of your research? And was there ever a moment when the horror of the holocaust threatened to undermine you?

There are just some moments I will never forget -- such as Bernie, who pried a mezuzah from his door frame as the Nazis dragged him from his home, and held it curled in his fist throughout the entire war – so that it took two years to straighten his fingers after liberation. Or how his mother promised him that he would not be shot in the head, only the chest – can you imagine making that promise to your child?! Or Gerda – who won the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and who survived a 350 mile march in January 1945 – because, she told me, her father had told her to wear her ski boots when she was taken from home. Or Mania, whose mastery of the German language saved her life multiple times during the war, when she was picked to work in office jobs instead of in hard labor; and who told me of Herr Baker, her German boss at one factory, who called the young Jewish women who were assigned to him Meine Kinder (my children) and who saved his workers from being selected by the Nazis during a concentration camp roundup. At Bergen Belsen, she slept in a barrack with 900 people and contracted typhoid – and would have died, if the British had not come then to liberate them. I make things up for 8 hours a day and I couldn't conceive of the horrors they faced, not in my wildest dreams. The flip side of this research, though, was the research I did with the director of Human Rights Enforcement Strategy and Policy in the Human Rights & Special Prosecutions section of the Department of Justice – a real-life Nazi hunter. Lest you wonder why this topic is still important, even after nearly 70 years – I will leave you with a story he told me. Years ago, after extensive work, his department finally was ready to question an 85 year old man who had been a Nazi guard and who was now living in Ohio. He refused to come in for questioning, so law enforcement professionals surrounded his house. He came outside with a gun. As the police lifted their own weapons he said, “Why you shoot at me? I not Jew.” Seventy years may have passed, but prejudice is alive and well. Knowing that he goes to work every day, and keeps looking for these perpetrators -- well, it made me very proud of my country.

You are astonishingly prolific. Are you always thinking ahead to your next novel? Do you have a file of ideas? How do you have this 6th sense about what is going to resonate with readers and the times?

I don't really think about my readers when I am coming up with a story (sorry)! I just write what I want and need to write. I have a few ideas percolating for the future; I'm not sure which one will rise to the surface first!

What also interested me so much about this novel is the whole idea of what is morally right and morally wrong, and when do the two ever switch place? Are we our actions? Or can we define ourselves in other ways? Can you talk a bit about this, please?

This was really the nugget that attracted me to the Wiesenthal book and to writing my own updated fictional account of what would happen if a Nazi came to a young woman nowadays and wanted to confess former sins. I was mulling whether or not you can ever atone for doing something really, really, really bad if you spend the whole rest of your life being a saint. Conversely, could someone who feels that they have a strong moral compass be compelled to do something horrible -- such as commit a murder? I think the line between good and evil is a fluctuating one and not nearly as rigid as any of us would like to believe. It's Kohlberg's morality dilemma: surely, if I told you to rob a pharmacy for drugs you'd tell me I was nuts. But what if your baby was sick and you had no money and no means to get medicine? Surely murder is wrong. But what if you walk in and find someone raping your wife? Suddenly the boundaries are blurry. I'd like to say I would not steal and I would not kill, no matter what...but until I'm in that situation of desperation, I just don't know.

I have to ask if you will talk about your first story, The Lobster Who Misunderstood.

Oh God, really? I don't remember the plot. I did illustrate it, though. I was five when I wrote it. I'm pretty impressed I knew the word "misunderstood." My mom still has a copy and I imagine one day if I do something to really annoy her she'll post it on eBay.

I always ask, what's obsessing you now and why?

I'm very excited about my 2014 book, obviously, because I'm in the thick of writing it. I’m not going to tell you too much about The Elephant Graveyard…but here’s a snippet of information. Ten years ago, Alice Metcalf was a researcher studying the reaction of elephants to grief – they are one of the few animal species that recognize and mourn for their dead, as humans do. Along with her husband, Thomas, she ran an elephant sanctuary – until one tragic night, an animal caretaker died in an accident and Alice disappeared, leaving behind only one witness: her three year old daughter, Jenna. Now, ten years later, Jenna is determined to find her mother – whom she believes would never leave her behind willingly. With the help of a publicly disgraced psychic, Jenna uncovers new information – and manages to convince the former detective in charge to reopen the case. This is a book about the lengths we go to for those who have left us behind; about the staying power of love; and about how three broken souls might have just the right pieces to mend each other. But – you heard it here first – this book also has THE BIGGEST TWIST I’ve ever written. Yes, even bigger than MY SISTER’S KEEPER.

And I always ask what question haven't I asked that I should have?

"How can I bake the cinnamon/chocolate roll that Minka's dad creates for her?" Actually I've already been asked this so much that I'm having a very talented baker friend open her test kitchen this weekend to whip this up. It was fictional - but not for long! The recipe will be posted on my website!

Published on January 03, 2013 17:54

January 2, 2013

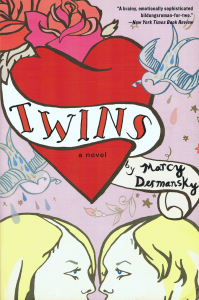

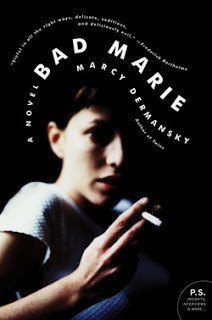

The divine Meg Pokrass interviews Marcy Dermansky, who talks about Bad Marie, Twins, swimming and why she put a standard poodle in everything she wrote

Huge thanks to Meg Pokrass for interviewing the sublime writer Marcy Dermansky. And huge thanks to Marcy for allowing herself to be interview.

Marcy Dermansky is the author of the novels Bad Marie and Twins. Bad Marie was a Barnes and Noble Fall Discover Great New Writers pick. Time Magazine pronounced Bad Marie “irresistible.” “Deliciously wicked,” proclaimed Slate. “Bad-ass,” said Esquire Magazine, naming Bad Marie one of the top novels of 2010. Marcy’s short fiction has been published widely in literal journals and anthologies, including Salon.com, FiveChapters, McSweeney’s, Indiana Review, and Fifty-TwoStories.

What is one (or more) of the loveliest things you have ever seen?

The ocean. Waves breaking. I am taken by the all of the it: the sand, the water, the sky. Also, my daughter Nina, who is three.

You like to swim. Please talk about the connection between swimming and creativity, if such a connection exists.

I love to swim. I love how quiet it is underwater. I am a lap swimmer, though I am not a terrifically fast swimmer. I love how I feel in the water: weightless, happy.

I do believe in a connection between swimming and creativity. For the most part, I don’t think anxious thoughts when I am swimming laps. Ideas come to me unbidden. Swimming laps, I feel more optimistic. Everything seems possible. It is almost like an electric switch that flips on. One day, I want to do join one of those polar bear clubs and try swimming in the ocean in the winter.

I was swimming a lot last summer, and through into the fall. I’ve been living in Germany for the last year and a half and have access to a wonderful outdoor lap pool, which closed in October. Since then, I have stopped. I don’t swimming in a crowded lap lane, or even worse, swimming laps in an open circle, passing the old swimmers and the talkers, getting passed by the fast swimmers. So it’s been months. I have gotten more writing done because I’ve had more time to sit at my desk. It’s great that I have been writing more, but I don’t feel as good about the writing as I do when I am swimming. I also miss those random bursts of optimistic thoughts. I miss the water.

Most writers talk about how much WHERE THEY LIVE inspires or influences their writing. Please talk about how WHERE YOU LIVE does not affect your writing. What remains the same no matter where you live when you are writing?

I have lived in many places that I have never written about it. Right now I live in a small city in Germany. This actually feels like a big thing to admit in an interview. If you were to look at my Facebook page, you will see that I have no current address listed. It is as if I am floating in space. Most people assume that I still live in New York. Many people, in fact, think that I am in Brooklyn, because if you are a New York writer, that is the place to live, but I used to live in Queens.

In some ways, I have to admit living in Germany has been good for my writing. This year, Nina started a free German kindergarten, which is actually preschool, and I get almost four hours a day to write. So, I have been writing. I have been working on a novel that in some ways is all about living in Germany. The main character is trapped on a spaceship, hurtling through space -- which is an awful lot what my life has felt like.

What themes obsess you? What themes entirely turn you off?

For a long time, I put a standard poodle in every thing I wrote. I recently deleted a standard poodle from my manuscript, deciding that the poodle was a distracting detail. I often send characters to Hawaii to go snorkeling, though I have never gone to Hawaii.

I don’t think in terms of theme when I write. Often, my characters tend to grapple with envy. I must be obsessed with this. The other day, opening Facebook, a successful writer posted a picture of her living room: “So so so good to be home,” she wrote. Suddenly, my whole life suddenly seemed shabby in comparison.

How does raising a kid inform the way you see the world?

The whole world has changed for me. I think all the time about the books that Nina likes best. I can recite the entirely of Slinky Malinki, a book from New Zealand about a mischievous cat. Nina laughs so easily and sometimes, she is just as quick to cry. Mainly, she is happy. There are gazillion things in my life that I can find to complain about, but Nina loves her life. She is energy. She is fun. She will also want to get out of the bed in the middle of the night, to look at the snow outside her window. I might want to be sleeping in my own bed, but I indulge her: pull up the blinds, let her climb onto the windowsill and look. I’ll have this moment of wonder, my arms around Nina’s small body to make sure she won’t fall, looking at the snow. It feels like my job to keep Nina happy and in doing so, I have to be happy too. It’s not made up happiness. It’s real. She is really, really good for me.

What are the occupational hazards of being both a mom and a writer?

Not having enough time to write. Being too tired to write, when you finally do having the time. Sometimes, not having enough ambition. Being content to hang around and play.

How much impact does your own childhood have on your writing?

It seems like when I don’t know where a character is from, the fall back is always New Jersey. I, of course, am from New Jersey. In my new novel set in outer space, I write about New Jersey. Memories from my childhood kept slipping in. For the most part, I don’t actively sit and think about my childhood, but I think it is also everything, who I am. My brain often feels like an enormous trunk, overly crammed with details. I don’t even know what it is in there, until I am in the middle of a sentence, and I pull something out.

What is the strangest thing anyone ever said to you as a writer?

My father always tells me that I should put more sex into everything that I write. Though he has said this for as long as I have been a writer, this comment continues to bug me. I also know that he is probably right. I want to sell more books. That said, there is not enough sex in my new novel.

Published on January 02, 2013 14:23

Krista Larson talks about clothing design, what dogs can teach us about good design, subjective beauty, and so much more

As a writer, I live in jeans, black tee-shirts and sneakers, but when I go on tour, I pull out all the stops, which means my Old Gringos, my bird dress, and whatever else I can find. One of the designers I absolutely adore is Krista Larson. Natural fabrics, gorgeous saturated colors, little touches that make everything she makes completely unique. Of course, I tracked Krista down to get her to talk about creativity and her art, and she was generous enough to agree to let me pester her with questions. Thank you, Krista.

Since this is a blog about creativity, can you talk about your creative process? What comes first--the design idea or the fabric?

I have been designing for almost 20 years now. Where did the time go? I would have to say that the fabric comes first. I try to come up with a great new color scheme that can be brought together by a great print. When I design, I try to think about garments that I would like or that are missing from my line. Maybe I'm going through a looser, baggie phase and I'm missing a longer oversized shirt......so I feel compelled to design one. I also try to take the input we get from our customers into consideration when designing. I might have a store owner that says she's missing "a cropped plain jacket". Those comments and suggestions stay in my head and eventually come out. I do like to please.

After choosing the fabric, I start sketching and then I might start sewing. If I have the time to get on the sewing machine, I am most creative. It's a wonderful means of expression.

Mistakes in clothing choices? Are they mistakes or is it life? I like taupe. Does it look good on me? Not so much. Do I care? Not so much. I love the color. So I try to put on a white shirt underneath. Is it a mistake that I wear that color? In some people's eyes it is. But we're all individuals, with our own likes and dislikes. I do think it is harder to be individual with so much media flying around us. There are looks that are considered "beautiful" or "gorgeous"....but in whom's eyes? It's all very subjective. It's hard to wrap one's brain around it all. I try to make things that I like or that I think look beautiful. I'm not going to please everyone.

So, ah hem, if you were going to suggest clothing for a spring author tour (packable pieces that don’t need ironing and look smashing), what would you suggest for me? (I know this is a trick question, but I’m asking anyway.)

I would probably need to know a little more about you....what your style is?.....are you a pants gal or a skirts gal? Do you like oversized or fitted? I love wrinkled linen but not everyone does. I've got some great stripes and little floral prints for Spring. I love skirts with a petticoat underneath, but that's me. I've got a wonderful blue plaid linen that's just divine with a crisp white shirt. If you need to look professional and minimal, I would suggest a black pinstriped taffeta skirt or slip with a black linen jacket. Pretty basic. One thing about my line is that I think it can go layered and funky or minimal and clean depending on fabric and color choice.

Tie dye, diping, spraying, stenciling. If I had more time, I could be so very creative. I have all these great ideas but I've yet to find the time to implement them. Soon....hopefully!

Your bio says you were always attracted to a different way of dressing. Can you talk about that? Are their mistakes that you think people make in choosing what to wear?

I was always a bit of a "misfit" when dressing in school. I didn't fit in in any click or group. I was always on the outside. I dressed differently. I try to think back as to why I did that?????? I don't know the answer. Something inside me was just compelled to be different. I liked different styles. It's ironic because I don't like attention but yet I dress so differently that it attracts attention. Hmmmm?

So, what’s the significance of the dogs on your hangtags? And what can dogs teach us about design?

I love dogs. Over the last 20 years, I have had 6 dogs. At one point, I had 5 in the house at the same time. It's a lot. For me, it's so hard if I have to leave town. I worry incessantly about them. They are truly like children. I become so attached. My 6th dog recently died in April of this year. He was the dog that no one wanted. In fact, he was returned twice because of a skin condition. No one wanted to take the time. I thought I could take a break after him, Wilbur.......I lasted a month and then I got two puppies (my seventh and eigth dogs). They come to work with me everyday. They are with me every day in the car. They are the thought that never leaves my mind. The constant love and happiness starring me in the face, over there, in the corner, flapping the tail. I know I am loved. I am not alone with dogs.

I guess if dogs could teach us anything about design, it would be to wear what's comfortable, that you don't mind getting dog slober on because I do so love to come close and snuggle.

Can you talk about your design philosophy?

Design philosophy? Hmmmm? Do I have one? What is it? Probably to design what I like, that I think others will like, that's beautiful, comfortable and lasts.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

I can't think of a single thing.....but I'm not a writer :)

Published on January 02, 2013 14:11

Nell Leyshon talks about her arresting new novel, The Colour of Milk, writing plays, delicious lunches, and so much more

Novelist and playwright Nell Leyshon is really an original. Her novel, The Colour of Milk, is narrated by a woman discovering the power of the written word--even as it eventually destroys her. It's a miracle of a read, and I'm just honored to have Nell here. Thank you, Nell.

The voice of The Colour of Milk is arresting and unique. Where did the voice come from? Was it always planned?

My original idea was born when the Royal Shakespeare Company organised a symposium for playwrights at Stratford. For three days we were given much food for thought and the idea was we would come up with ideas for plays on a linked theme. I put forward an idea for a play about a young woman learning to read.

The season never happened and I was left with my idea that kept nagging in my head. I was determined to write it and realised I could turn it into a novel. The voice of Mary came to me the same day that I made the decision to write. I caught the first line of the novel in my head - this is my book and i am writing it by my own hand - and the rest followed. It was one of those books which comes as a gift and all I had to do was turn up and write it. However, that makes it sound easier than it was; as with all pieces of writing, there was a lot of rewriting and refining after that.

What was the research for this book like? Were there any surprises?

I have to confess I hardly did any research. I wrote the book first and then checked to see whether I had imagined correctly! If I do too much research before writing, I find myself tied into the facts, and there is always a temptation to load the writing with everything you've found out.

I remember finding out one particular piece of background which I thought I would need, but that never made it into the book. Mary just didn't care about it.

For Mary, the world of books becomes both a reward and a punishment for Mary, which in the end destroys her. Why do you think education is so dangerous?

Education is power. Without the ability to read and write, we are helpless. Therefore to keep a sector of society down, it is necessary to keep education back. For me education changed everything. I went to university as a mature student and I know my brain was wired differently before and after.

I am always interested in those who don't have power: I do believe that many many talented people never manage to speak out and use their talents because of lack of education and opportunity.

You're also a prize-winning playwright as well as a novelist. Do you prefer one form over another? Is one ore rewarding and if so, why and how?

I love writing both. In fact, I keep expecting someone to say I have to make a decision between them, but it hasn't happened yet... Drama is different because I become all those different people, and the main challenges are structural, architectural. I also have to engage with the real world of theatre between and during drafts, Writing prose is secretive - I didn't show anyone a word of The Colour of Milk until it was done. In fact, I didn't even tell anyone about it. Writing drama is like being married; writing prose is having an affair.

Why and how do you write? What's your daily writing life like?

I write every day, just as any job. I can write quickly but that depends on how it's going and how easily it's coming. I live by the sea and walk each morning (I am just back from a walk) and then come home and write. I do have interruptions: teaching (which I love), working with creative writing and mental health and addiction (which I also love), meals, emailing etc., but I do work hard as I seem to have many deadlines. I have the mixture of prose and drama, and I also write for radio.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Two things. First, the play I am currently writing. I am on my second draft and it's taken longer than I hoped. It's technically difficult and is really challenging me. Second, I have a complete draft of a novel on my desk waiting for me to come back to it. I haven't read a word of it since I printed it out and I am really excited about getting back to it in the new year. Yet again, I haven't told anyone anything about it.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Ha ha. How do you keep going writing on your own at your desk all day long? The answer is I reward myself with food. If I just get this bit done, then I can have a delicious lunch.

Published on January 02, 2013 13:59

Evan Handler talks about It's Only Temporary, Time on Fire, how brutal honesty can save you, and so much more

Time on Fire was based on your hit off Broadway play, about being diagnosed with leukemia at 24 - and against all odds, surviving it. What made you decide to turn it into a book?A book was what I wanted to write from the beginning. But, I was an actor, with a kind of blossoming, but stopped-dead-in-its-tracks-by-illness, NY reputation. At 24, after starring repeatedly on Broadway, I disappeared, and at 29 I was attempting to reemerge. Everyone I knew had lived a fairly normal, predictable mid-to-late 20's existence during my absence, while I'd been hidden away in what felt like a secret society, fighting to survive. I was unrecognizable - both literally, and figuratively. When I started to spend time with peers - you know, the people you gravitate toward, due to shared values and experiences - I had little patience for the things that were concerning them, and they had zero understanding of any of the things that had been, and were, consuming me. There were no shared experiences. But I didn't have much interest in befriending people who'd also survived devastating cancers, and, so far as I knew, there weren't very many of them around. It might sound trite, but I wondered whether telling the story of where I'd been might help to create some sort of bridge between me, and the people I used to know. There was a very concrete desire to reconnect, by communicating where I'd been, and what it had meant to (and done to) me. But, again, I was an actor. I didn't think anyone in publishing would take a book proposal very seriously. But I thought they might accept an invitation to the theater from an actor they might have heard of, or even seen perform. So I decided to write an extremely condensed (compared to a book; for a solo stage monologue, with two full acts and a 110 minute running time, it was enormous; I called it "my minimalist epic), but complete, version of the story specifically for the stage, specifically for the purpose of garnering attention from the publishing world.That was the most personal and intimate motivation. In addition, as I made my way though the comic horror story of my hospitalizations, I found every piece of literature or cinema on the subject to be woefully inaccurate and inauthentic. Just an awful heap of maudlin, sentimental, or artificially spiritually uplifting dreck. Like Aspartame for the Soul. I felt that the degree to which the world I'd descended into was kept hidden from everyone walking around free and easy couldn't be accidental, and I wanted very much to pull back the curtain and reveal what was actually going on. Where, I'm sorry to say, all the people I'd left behind were, eventually, going to travel themselves. I'd just had a preview at a precocious age.What I so deeply admired in the book was the no-holds-barred almost brutal (and often hilarious) honesty - slamming certain doctors, revealing not so kind behavior to your then girlfriend. Did you worry about the reactions others might have?I did. I do. But it was very clear to me that brutal honesty was the only thing I had to offer, that might set me apart from all the other poor saps who also thought their illness experiences were meaningful enough to share. It's not like there has ever been a drought of material on the subject. It's just, prior to 1996, I'm not sure a lot of it was very good. I just couldn't believe that everyone's experiences could have been as cut and dried as the stories I saw being told. There were the "cancer is the best thing that ever happened to me" stories. I have never for a moment related to that. The "I found God/love/family/ability to speak to dead people via cancer" stories. Also not my cup of tea. And, reams and reams of the "he tried as hard as he could and was so heroic but still just didn't quite make it" stories. Which, I still think, are about as awful an example to continue to pump into the world as one can. So, I did have a very real impulse, throughout and beyond the illness, to continue to exist as an example of what was accomplishable, and to use that existence to put some more realistic, and useful, messaging into the world.There is a passage in the book, "If You Meet the Buddah on the Road Kill Hiim," that spoke to me very deeply. It speaks of the intersection of personal history, and the advancement of society, and hails the telling of one's own story as the force by which society is advanced (apologies for the paraphrasing). It became my guiding principle in writing the story.To go back to your question, I developed both the stage play and the book by reading most of the passages aloud at a theater company in New York I had a history with (Naked Angeles). I began to call it "The Oral HIstory of Me (as told to myself)." And I learned that, if executed enjoyably, people most want to hear what you least want to reveal. With emphasis, of course, on "if executed enjoyably." Revelations of the deeply personal, and self indictments, can be either riveting, or revolting. It's a fine line.You said, in Time on Fire, that you must have been hell to be around, but this behavior saved your life. Can you talk a bit about this?I found myself twenty four years old, diagnosed with an almost certainly fatal blood disease, and falling through almost every conceivable crack one could stumble into. The world famous hospital I checked into was understaffed with nurses, and overstaffed with outrageously arrogant and callous physicians - and that doesn't include the sadists, who do exist in measurable numbers. I discovered, to my horror, that the battle I'd witnessed all my life between those who want to do a great job, and those who discourage that because it pressures them to work harder, existed even in an environment wherein anything other than superb performances would lead to unnecessary additional deaths. When you find yourself suddenly needing all the help you can get, and simultaneously realize the depth of indifference, if not hostility, of those supposedly devoted to your attempted rescue, it can lead to some very necessary defensive measures. For example, when I was first hospitalized in 1985, I was told I had to perform relentless hygienic precautions to avoid lethal infections. But, I couldn't get the hospital staff to perform even the most minimal hygienic precautions their own regulations required. They would not put on gloves and gowns upon entering my room and handling me. They would not adequately sterilize rubber ports before piercing them with needles and injecting substances. They wouldn't even leave a thermometer in my mouth long enough to register an accurate temperature, when fever was the key sign of the expected infections that would need immediate antibiotic treatment. When I asked that these procedures be performed properly, I was told that the worker didn't have enough time, and chided - or threatened - for making their lives difficult. "Why can't you be more like Andy down the hall?" I was once asked. "He comes around with us and helps us make the beds." That was one of the kinder comments. I was also told, the morning after my girlfriend stopped a nurse from injecting me with a drug I was known to have a bad reaction to, and that had been taken off my chart as an option, "People are saying your girlfriend has a bad attitude. That can affect your care here, you know."

There also weren't enough clean sheets and pillowcases to go around. My girlfriend and I had to go to other floors of the hospital, take them from storage cabinets and store up an adequate supply each day. When you live this way for a while, you become suspicious of everyone's devotion to doing a good job, and trust no one to do so. You insist on instructing, and double checking, everyone. At least, you do if you want to live, more than you want to be liked. And, well...it's probably not hard for anyone to imagine why that level of paranoia and mistrust could make someone difficult to tolerate. But it might also explain why someone managed to get well under very difficult circumstances.And how do you live well, knowing that time is limited?I make believe time is not limited, when it's too painful to recognize that it is. And I remind myself that time is limited, when I find myself taking too much for granted. There's a line in one of the books, I'm not even sure which one, that says "I try to remind myself to live each day as if it could be my last. But living each day as if it might be my last usually makes me too sad to enjoy them" I would say that the difficulty of that conundrum is the balance that "It's Only Temporary" tries to describe.Did you discover anything new and surprising about yourself in the writing - and what was the writing like? How did you ever find the time while being a successful actor?I think what I discovered, if I can be forgiven for saying so, is that I am a writer. I had never written anything other than school assignments before writing the material that became "Time on Fire." Yet I always told people that if I couldn't be an actor, I'd probably be a writer. I wrote some passages on a very early, very large, DOS laptop computer during the hospitalizations, but I never owned a printer, and so never read any of them back after they'd been written. A few years later, while performing at Lincoln Center in the John Guare play "Six Degrees of Separation," which was pretty much my big comeback project, I handed off the 5.25 inch floppy disks to someone in the offices, and they handed me back these pages that fascinated me. I was amazed by what I'd written, and - even just a few years later -I could hardly recognize myself as the person who'd written them. I remember one passage in particular: "Why am I alive today? Just to wait until tomorrow, to see if I feel better then?" It's a startling jotting to come across, while you're starring on Broadway, surrounded by vibrant new friends. It's one of those moments when you can really see how far you've traveled, even if you'd been feeling that you hadn't traveled very far.I took some of those writings, reworked and rearranged, and added a good deal, and began bringing them to Naked Angels' Tuesday Nights @9 reading series. People are invited to bring in ten minutes' worth of whatever they're working on and read it out loud to the 25-100 people who might have shown up to listen that night. Generally plays and screenplays, but all sorts of writing is allowed. And, the response to the material was perfectly in tune with what I wanted it to be: people gasped in horror over what they were hearing, then forgot their horror and laughed uproariously, then became horrified all over again, along with the added horror that they'd allowed themselves to laugh at all. Then, they'd forget and laugh again. When that happened, I thought Hey, I think I'm on to something here. So, I made it my mission to bring in ten minutes every week. It was an amazing experience, to tell my story in a serialized fashion like that. It was the exact experience I'd craved: the opportunity to tell my community where I'd disappeared to, and what had happened to me there. And/or, if I preferred, to craft whatever kind of image I wanted to craft in regard to how I felt about all I'd been through. I'd felt for some time that a lot of people who'd only met me since the illness were wondering, "What happened to this guy to make him the way he is?" So, I took it upon myself to explain. And, in doing that, I got a pretty strong sense that there would be a lot of value in answering the same question for people who had never even met me. That the story had a value beyond me, and my little world of people close to me.Acting, to me, seems so external, while writing most definitely is internal. Do you prefer one over the other? And if so, why?I think you're right that the publicly displayed, finished product of a performance is far more external. Perhaps even rehearsals, too, as those are also conducted in collaboration with others. But I think a lot of the preparation I do as an actor is just as internal as the writing I do. Both require extended periods of rumination, which I enjoy. Both are aided by rumination that can be conducted while out and about, observing others, which I also enjoy. Both require specificity to be good. Both are probably also aided by rumination fueled by alcohol, which I still enjoy, but much more moderately than in the past. They're both huge parts daydreaming and imagining, wondering what the effect of various choices might be. As an actor, those choices are then tested out and explored in collaboration with others, and eventually displayed either in front of an audience, or a camera for an audience's consumption. As a writer, they're written down and passed on via the prism of each reader's mind. Unless you read it aloud to an audience first, which is how I wrote most of each of my books. But, be forewarned about that choice. You will have editors telling you that what you felt worked in front of the audience doesn't work by itself on the page. And I have little good advice to help with that problem.What's obsessing you now and why?The only things obsessing me now are how to get my daughter to school in the morning, or who's going to pick her up in the afternoon. How to get dinner on the table in the evening. How to arrange transportation to drop the car off at the mechanic. Who's going to stop at the store to get the groceries. Who drives who where, and when. Who's going to make which phone calls, and send such-and-such an email. Just free floating household obsessions. Closely akin to free floating anxiety. I'm in search of an obsession worthy of my obsessiveness.What question didn't I ask that I should have?Well, you didn't ask me whether Kristin Davis is really nice, or whether it's fun to do so many sex scenes with beautiful actresses. But, that's okay. I'm on record about those things, repeatedly. And my responses are identical to the responses given by everyone else who's ever been asked the same questions.

Published on January 02, 2013 13:51

December 26, 2012

David Abrams talks about Fobbit, screwball comedy, being paid to read the Bible, and so much more

David Abrams debut, Fobbit, a harrowingly funny novel about the Iraq War, was not only a New York Times notable book of 2012, but it zoomed onto the Best Books Lists from Barnes & Noble, Paste, Amazon, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Publishers Weekly--and my own personal list, too. He's also the genius behind the blog, The Quivering Pen, and truthfully, one of the warmest, most hilarious human beings on the planet. I'll thrilled to finally have him on the blog! Thank you, David!

So, every writer's least favorite question, sometimes, but the one readers always want to know: Tell us what sparked the writing of Fobbit?

What sparks any novel? A word? An image? An off-hand comment from a co-worker, a spouse, or a stranger? In the case of Fobbit, it was a little of all of that. Maybe it was the fact that I read Catch-22, Don Quixote, and Jarhead on my first deployment into a war zone (Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2005). Maybe it was the time when I was sitting at my desk in the U.S. Army’s Task Force Baghdad Headquarters and someone in the next cubicle was complaining about a paper cut they’d just gotten after a printer jam while, at the same time, we were hearing a report through the overhead speakers of another casualty in the war—a soldier blown apart into five different pieces from a roadside bomb. Or maybe it was my agent emailing me—after unsuccessfully shopping around my “Iraq War memoir” manuscript to New York publishers—to advise that maybe what this war really needed was a novel—a work of fiction that would hit home to a reading public who’d grown numb to a nation at war. It was all of those things—a culmination of factors that led me to turn away from truthfully recounting my year-long deployment to Iraq as a much-despised “fobbit” and focus on the medium of lies instead. Near the end of my tour of duty, I realized fiction would be the most effective megaphone I could use to tell people about my war experience. And so, I set to work writing a comedy about my days in Baghdad with the 3rd Infantry Division.

Fobbit's been compared to Catch-22 in its wild, black humor and its raw look at the War. You even include a funny homage to Heller's book in your novel, by having a character reading Catch-22. Does this fantastic comparison make you more nervous about writing your next book or does it save you, or a little of both?

The debt I owe Joseph Heller for artistic inspiration is incalculable—as is the debt I owe Raymond Carver, Joyce Carol Oates, Charles Dickens, Richard Ford, Flannery O’Connor, Victor Hugo, and any number of other literary lampposts which have lit my path. In the case of Catch-22, it obviously had a direct impact in the way Fobbit turned out and since I knew the comparisons would be inevitable, I decided to give the book its own little cameo in my novel. I read Heller’s novel for the first time when I was on my way to war—literally on my way: I started on page 1 after I’d boarded the plane at Fort Stewart, Georgia and had reached the midway point by the time we touched down in Kuwait, the 3rd ID’s staging ground before we moved north to Iraq. Catch-22 was unlike anything I’d ever read. There’s slapstick on one page and horror on the next. It’s not an easy book to read; it’s illogical and irrational in structure; there are as many characters as an Osmond Family Thanksgiving guest list; and you have to work your way toward its pleasures….but when you get there, those rewards are immeasurable. I should add that Catch-22 is not the only influence behind Fobbit. I was raised on a diet of TV shows that poked fun at the military: Hogan’s Heroes, Gomer Pyle, and M*A*S*H. Those shows were subversive and, though I didn’t realize it at the time, they set the stage for the way I always root for the underdog. The little guys (the privates) always got their way while the higher echelons (the officers) came off looking like fools. Discipline was turned upside down, creating chaos. And out of that chaos came comedy. So Fobbit is as much Gomer Pyle as it is Yossarian.

I loved that you focused on the noncombat units of the Iraq War. As a former army public affairs specialist, you have an insider's unique perspective, so how much is exaggerated and how much is dead-on true?

If comedy is truth stretched out on a wad of Silly-Putty, then there’s probably a lot of truth at the heart of Fobbit. I don’t think I want to get into naming the specific elements of the novel which really happened or are daily practices of the Army at war because nearly everything in the novel is a hybrid—a fictual faction—but I can tell you there are two sections of the book which stick pretty close to the truth: the tragic scene at the on Al-Aaimmah bridge where nearly a thousand Iraqis were killed in a stampede; and Captain Abe Shrinkle’s flashback to a disastrous date in high school. The bridge stampede happened while I was in Iraq, and that date was pretty close to my own romantic fumble in junior high. For the rest of the book, I tried to filter the essence of truth through comedy. While I was writing Fobbit, I kept circling back to one of my favorite quotes from Flannery O’Connor: “To the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.” In order to get readers’ attention, I did a lot of shouting and billboard-painting in this book.

What's your writing life like?

I balance my writing routine with the demands of a full-time day job, and the pleasures of a very rich, happy married life (my wife and I are empty-nesters now, but we like to spend most of our time together). These things squeeze the rest of my day into small compartments. So, in my quest for better time management, I’ve started getting up at 3:30 every morning to work on my creative writing. The house is dark and quiet. It’s just me, the keyboard, a mug of coffee, and my classical music iTunes playlist. It’s an ungodly hour, but I find these are my most fertile hours. Sadly, I don’t spend all of those hours writing fiction. Lack of self-discipline is the biggest monster on my back. That’s why you’ll usually find me checking email, Tweeting, blogging, and any number of other distractions when I should be writing fiction. When I do write, it’s usually in these big bursts—lung-burning sprints to a finish line—where I write an entire short story in one sitting, or spend three days in isolation trying to get through 50 pages of my novel.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Apart from my blog, The Quivering Pen, which is always an obsession, I’ve been consumed with revising my next novel. It’s a screwball comedy set in the Golden Age of Hollywood—something pretty far removed from the bloody grit of the Iraq War. In a nutshell, it’s about a popular child actor and his adult stunt double and the trouble they get into when the kid kills a rival studio’s mascot—a scrappy little dog who always opened the studio’s films with a “Yip-yip-a-rooo!” similar to the MGM lion’s roar. On a larger level, it’s about identity, loyalty, and the conflict of protecting someone you’ve grown to dislike.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

You didn’t ask me about the time my father, a Baptist minister, paid me to read the Bible (I made it as far as Leviticus that year and earned $35); the name of my first dog (Shane, a chocolate Labrador Retriever); three things I love about my wife (her sense of fairness, the depth of her voice, and the way she collapses with laughter when I’m on a really good roll with snappy one-liners); my favorite non-writing, non-reading passion (cooking); the two TV shows which didn’t deserve to die early deaths (Southland and Better Off Ted); which type of chocolate I prefer (milk); and the moment I really, truly grew up (September 22, 1984 when my first child was born: For nine months, he’d been this mystery--identity unknown, a shifting shape behind the barrier of my wife's skin--but now here he was, pink and wet and complete, coming out of my wife's body with his arms springing open wide, as if he was at the end of a dream about falling from heaven). But then again, how could you have known those were the questions you should have asked?

The Quivering Pen , a blog about booksFollow David on Facebook Follow David on Twitter: @ImDavidAbrams

Published on December 26, 2012 10:37

The divine Meg Pokrass interviews the sublime Bill Roorbach about why books are alive, Life Among Giants and so much more

Life Among Giants is one of my favorite books of the year and I'm so thrilled that Meg Pokrass in interviewing the author, Bill Roorbach. He's penned eight books, including the Flannery O'Connor Prize and O. Henry Prize winner Big Bend, Into Woods and Temple Stream, and his craft book, Writing Life Stories, is used in writing programs around the world. Recently Bill was even a judge on Food Network All Star Challenge, evaluating incredible life stories cakes. . His work has been published in Harper's, The Atlantic Monthly, Playboy, The New York Times Magazine, Granta, New York, and dozens of other magazines and journals. A comic video memoir about his tragic music career, "I Used to Play in Bands," and all kinds of other work, including a current blog on writers and writing and just about everything else (with author David Gessner) is online at www.billanddavescocktailhour.com. Thank you so, so much, Bill and Meg!

MP: Please talk about character development in writing Life Among Giants. Where do your very real characters spring from? How do we find characters both within ourselves and outside of ourselves as writers? How much happens IN the process of writing? Anything here relating to process of character development?

BR: It still really amazes me how people emerge as soon as I start writing about them. In this case, I got a kid named David “Lizard” Hochmeyer talking, telling a story I had no idea what it would be. He was smart, personable, huge, a great athlete, nothing like me, except in his interest in dance. Which in his case has to do with a world-famous ballerina who lives in a mansion across the way. He goes over there to rescue her and fate is unleashed. So then I have to find out who she is. It all happens in the process of writing, since I count the daydreaming before and during the making of the book part of the process. And Life Among Giants has a lot of characters from all kinds of backgrounds. I built them from scraps in my head, bits and pieces of all the people I’ve met, my own emotions, my own experiences, experiences I’ve heard about, read about, mused. Much comes from research, though never immediately. Lizard ends up in the NFL—I had to study to get some sense of what that life would be like. He’s a chef in the end. I worked in restaurants and love to cook, so I had some clues, but really Lizard had to tell me what it was really like, and he was glad to.

MP: So, maybe your brain is full of people you know, or have met, or have seen glimpses of. Maybe some people are real and others are absorbed over your lifetime from books or movies?

BR: No, once they’re in my brain, they’re not real. Right?

MP… and all of this mixes with who you are and the way you see. I love the idea that you are coaxing your characters out in the process of writing them. This leads me to think we are all far more multifaceted than we know we are, and only as writers when we sit down to write does this actually become clear. Your brain is like a big world.

BR: : It’s a big multi-media machine, and we are the original cloud.

MP: Have you had mentors in your writing life at different points? Can you talk about the importance of mentors here a bit?

BR: I don't know what it is with me and mentors. I have always resisted them and so never really have had a long-term mentor. Great teachers, though. One in college told me I’d never be a writer, and that’s what made me a writer. Philip Lopate was a big influence in grad school, got me writing personal essays, oddly in a fiction class he taught.

MP: Who are your heroes?

BR: Van Morrison. Alice Munro. The secular Jesus. Nureyev. Tom Brady. Bernie Sanders. Bobby Flay. Etc.

MP: Who are your favorite filmmakers?

BR: Sofia Coppola.

MP: What makes us love (not just identify with) a character/ a voice?

BR: I don’t know, of course. But I think it’s similar to what makes friendship possible: vulnerability, and something in return.

MP: Giants on the Road: How has your book tour been? Please give us highlights and terrify us with stories about the first leg of this journey. BR: This tour is nuts and great, so old-fashioned. i feel so lucky and exhausted. Highlights have been Big Hat Books in Indianapolis, so fun and cozy, with bottles of wine and good talk beforehand, and a low-key talk. Plus, my second cousin Gay Burkhart turned up. She said my late mother was the funniest woman she ever met. She is the granddaughter of my grandfather's older brother. And looks a little like my mom. Low point was probably Dayton, Ohio, where I don't know anyone and where I had the wrong address for the store I was supposed to talk at, ending up at a mall with no bookstore at all! Scramble, scramble and I barely made it to the right address on time. And no one there. But then turn up a couple, the female of which is the sister of a FB friend of mine, all the connection we needed to go out and have a drink after, lifesaving. The next morning to Miami, which was great. Then, two days offish and time with my old guitar friend Jonny Z, plus swimming and biking and general debauchery. Next up to Atlanta, where lots of my family lives. Fun! And a great talk at the Georgia Center for the Book, great crowd, given all the family, but also a big glowing full-page review in the Atlanta paper. Boston a couple of nights ago, or Andover, actually, Boston area, really nice store in a really nice town. Then home, with a couple of stops to sign books informally at stores I'm happy to say had books to sign! Home to 12 hours sleep, which I haven't done since I was 12 months old.

MP: Well, all of this sounds terribly lively. Bill, books are DEAD, aren’t they?

BR: Books are alive. They are just hiding. Though they recognize their allies and emerge just when we need them.

Published on December 26, 2012 10:28

December 17, 2012

Is This Tomorrow now on NetGalley

I'm thrilled and honored to have Is This Tomorrow now on NetGalley. If you're a reviewer, librarian, blogger or educator, you may be able to read my novel for free on your e-reader. Click here for details. Plus, check out the other Algonquin titles!

Published on December 17, 2012 08:28

December 16, 2012

Meg Pokrass interviews Jonathan Evison, who talks about why he's the last person on earth you'd want health tips from, social networking, The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving and so much more

\

\

Fellow Algonquin author. The most generous writer you'll ever meet. Smart. Funny and deeply talented. All adjectives to describe Jonathan Evison, bestselling, rapturously praised author of West of here and The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving. I'm thrilled that Meg Pokrass (who is also, smart, funny, generous, and deeply talented) is doing these honors. Thank you both!

MP: My background was in theater, I acted for many years. When the run of a show ends, it was very sad. Not only are you saying goodbye to real people (your fellow actors) you are also saying goodbye to your character, both internally and externally. Closing nights were sad as hell for me...This leads me to a question about completion in novel-writing. When a novel has been completed, is there a feeling that may be akin to an actor's closing night performance? Do you continue to experience your character's perspectives for a while?

JE: Well, see, they're never quite done, as with a theater production. Not until my editor pries them from my hand. I just keep working them and working them until that day. The truth is, by the time they're actually "done"--if I've done my job right-- I should be sick of them. But the characters really do live with me forever, like dead people. Even closer than dead people, really, because their hopes and fears were my hopes and fears. Long after I put them on the shelf, I still see things as my characters would have seen them. In this way, the whole act of novel writing makes me more expansive person.

MP: Please talk about the crucial ingredient/ingredients toward developing real characters, creating fictional people who you make become real, and who we care about…

JE: If I have one native skill, or gift, it is that I am empathic, and always have been. I relish perspectives outside of my own. I want to see the world through as many eyes as I possibly can, and my characters allow me to do that--or at least approximate doing that. It is a privilege and a joy to inhabit my characters-- to suffer and rejoice with them, to feel their aches, to learn from their experience, to taste their victories and defeats. I get to climb mountains, and buried loved ones, and feel in full measure, the gratitude and regret of my characters. Ultimately, I get to redeem them. And all without getting out of my pajamas.

MP: A strong natural sense of empathy seems an essential trait for a novelist. I remember an interview/discussion between Daniel Handler and Richard Ford here at City Arts and Lectures. Handler asked Ford "How do we create loveable characters? Any thoughts on this subject of developing likeable and/or lovable characters?

JE: Well, love them. Be fair to them. Make them suffer, but don't forsake them. Do not condemn them, or judge them, with your mighty authorial voice. Don't be disgusted by them when they're at their very worst, which is often. Inhabit you characters, body and soul, and you will love them no matter how flawed they are.

MP: And, what is important to you when writing characters which are not particularly …er… lovable?

JE: The people you described sound like my heroes. I want my people to be as flawed as possible. All I ask of them is that they are making some small effort--and likely failing-- to get better, to improve themselves. Otherwise, I'm not interested in them. In this respect, I don't write characters I don't like, at least on some level. Except, say, for a few irredeemable villains, like John Tobin, in West of Here, who serves more as an instrument to the story than a character.

MP: What do you love the most about readings, and public appearances? What are some of the most special events you've experienced? Conversely, what is hard about being totally out there, on the road... Do you get tired and depleted? Are there tricks to keeping yourself healthy and ways to combat some of this hectic-ness?

JE: After twenty years of having no readers at all, I really appreciate having them now. It is a pleasure to interact with people who want to talk about this thing that I love to do more than anything else, this thing I live to do. I love it most when I'm on the road, and I get kidnapped, by say, Jenny Shank and her merry band of pranksters in Denver, or the staff of Boswell Books in Milwaukee, and we go out and drink beer as a group have wonderful drunken discourse, and I get to know a town a little bit, bar by bar. Sometimes I'll get to take in a museum, or somebody will give me a driving tour of a city. As far as tips for staying healthy on the road, I'm the last person on earth you'd want tips from. I routinely fill my hotel bathtub with ice and load it up with a case of beer. I eat French Dips and pizza as much as anything else. I sleep about five hours a night, and unless I'm lucky enough to have an off-day, I never exercise. I miss my family dearly, but I manage to keep myself busy, and mostly out of trouble. Of course, I get very little writing done, aside from notes, though the notes help so much in the gestation stage, which is usually where I'm at come tour time. So by the time I get back to my writing routine, I'm working with some pretty well developed material.

MP: How has Facebook and other social media been for you?

JE: I love social networking. I like to hear as many voices as possible at all times. I love the great cacophony of humanity--and never before have I been able to sit on a great big virtual street corner like FB, and hear so many voices. I have an ungodly number of Facebook friends, but honestly, I've personally met probably 70% of them, if only briefly. Thus, being a FB friend is generally my second point of connectivity with a person. Not that I don't befriend people who reach out. In my opinion, social networking is only a good idea for those writers who really enjoy and embrace it. If you don't enjoy it, you're not bringing anything to the conversation, and people are gonna' get that. So, why bother? Also, FB and Twitter and and the like are an amazing resource, not only for topical stuff like news links, bet for stuff like: "Hey, we're looking for midwife in Kitsap County. Any recs?" Or, "Hey, know any great bars in Baltimore?"

Published on December 16, 2012 13:20